|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art historian

|

|

Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. (Gen 1, 2-3)

CaixaForum Madrid is currently exhibiting 245 polaroids from the Genesis series by Sebastião Salgado (born in Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 1944) until May 4 — an exhibition which serves as a testimony to one of world’s most relevant contemporary photographers. He was awarded the prestigious Príncipe de Asturias de las Artes award in 1998 and during his career he has worked with some of the best photography agencies in the world, such as Sygma, Gamma and Magnum, before setting up his own, Amazonas Images. In this exhibition the photographer shows us the incredible, remote places he visited during his 32 expeditions lasting eight years, just before he turned 70.

The first thing you notice in Salgado’s photography is his powerful aesthetic sense; and his message slowly, gradually seeps through from the images, slow and gradual as elephant’s footprints on the soil. What you see in his photos is an area occupying 46% of the planet, and which to this day is virgin land — the same as it was on the first day, according to Genesis.

We decided to carry out more in-depth research on the theories and biography of this artist, certain as we were that someone like Sebastião Salgado should have much to say about an area of life and of the heart that is only open to those with a certain view of the world. Rhythm, Coherence, Passion. And we suddenly realize that it’s his inner journey that we’re really interested in.

Salgado is a man of clear vision and slow speech; his spoken English has an attractive Brazilian Portuguese hint to it, and his slow speech is not due to linguistic hesitation, but is the sign of a man who has seen much of the world and, more importantly, a man who observes mindfully. You see this in his careful choice of answers, and in how well he expresses them.

Like all good photographers, he has made a pact with slowness. “I walk a lot, I do some of my reporting on foot because I use the time to look around and to feel life, to feel nature. Slowly. If we don’t do it slowly, we end up burning out. Most often, the essence lies in the curves, in the twists and turns of the journey, not in the straight lines.” He compares photographers to hunters because they both live in waiting, fully immersed in their own authentic processes. “We must experience the pleasure of waiting.”

Before the Genesis project, Salgado had focused on photographing people, who he sees in a very different light, broader, more real: a vision we’d like to share with him. “I have learned that, at times, where there is life, there is also death. In Kazakhstan, the same phosphate used in agricultural fertilizer is also used as napalm, an effective combat weapon. In Bangladesh, the same fabric components found in jute are used both for the production of sacks for cereals as well as for the sand-filled sacks used to build trenches in wars. When the jute sack is attacked by bullets, it closes itself thereby keeping the sand inside and protecting the soldiers.”

Listening to his life story, we realized that Salgado is one of those people whose vision of the world and of people we’d like our own children to have. By the time they reach the age when they’re overcome by a powerful natural curiosity about the world and they look for answers in stories and pictures, it would be wonderful to sit them down on the ground, and let them look up and listen to a wise man in front of them, whose eyes, the eyes of a hunter of slow images, are filled with real, genuine stories: “When I was in Ethiopia I travelled 850 km on foot. I discovered that that was the origin of all the fertile land from the banks of the Nile. I travelled to a Christian community, where Egypt’s first jews settled. It was just like landing in the middle of the Old Testament. Rather than being a journey of 850 km, I see it as a journey of 6,000 years inside myself.”

De Mi Tierra a la Tierra (From My Land to the Earth) (La Fábrica) is the title of his memoir, in which he talks about how the Genesis project begins in the Galapagos Islands, following in the footsteps of Darwin and taking the The Voyage of the Beagle as its guide. This is where Salgado learned that man is not the first species gifted with reason. He also describes certain unexpected situations he discovered in the natural world, for example that when the time comes for the common gannet to mate, it’s the female that chooses the male. The males introduce themselves before her, they dance, open their wings and show off their body. When the female makes her decision as to which male to mate, they fly off together for about 15 minutes. One by one, all the females follow this ritual of allowing the males to court them and then choosing one. For the duration of that season, this will be the female’s only mate and the father of its babies.

BLACK-BROWED ALBATROSS IN THE ARCHIPELAGO OF THE WILLIS ISLAND, SOUTH GEORGIA, 2009.

Although the Hebrew name of the first book of the Bible comes from its first word, Beresit (meaning “in the beginning”), its Greek name is Genesis, in reference to the “origin” of the world and of man. Salgado is a non-believer, yet his purpose with the Genesis project is to show “the dignity, the beauty of life in all its aspects. And of course the fact that we all share the same origin.” He told us about the time spent on the Galapagos Islands, about how he once noticed the front legs of an iguana and how his imagination led him to see in them the hand of a Medieval warrior, clad in chain mail. The incident made him suddenly aware of the similarities between species, and led him to decide on the name of the project: Genesis.

Looking at this photo while we were passing through the halls in front of the Botanical Gardens, we all had the same doubt: Is that King Arthur’s hand? Or it could it be Ironman’s?!

SEA IGUANA, GALAPAGOS ISLANDS, ECUADOR, 2004

Salgado was born on a farm in the Brazilian mainland, where he learned to observe and to love the lights around him; he grew up under densely overcast skies and storms through which light would filter. He spent his childhood among large expanses of land, streams, rain seasons and long seasonal migrations among thousands of oxen.

At the age of 20 he fell in love with his other half, Lélia. They arrived in Paris together in 1970 — they were fleeing the political turmoil in Brazil at the time. During his first European summer and in a Two CV, they drove all the way to Geneva just to purchase some photographic material at a better price. Lélia had to photograph buildings for her classes at the Faculty of Architecture. Although neither of the two had any previous knowledge of photography, they both instantly fell in love with it. And that is how photography became his way of life. He discovered Africa while working as an economist at the World Coffee Organization — he became passionate about the continent and wanted photograph it constantly. He gradually left his day job and began to consider himself a full-time photographer.

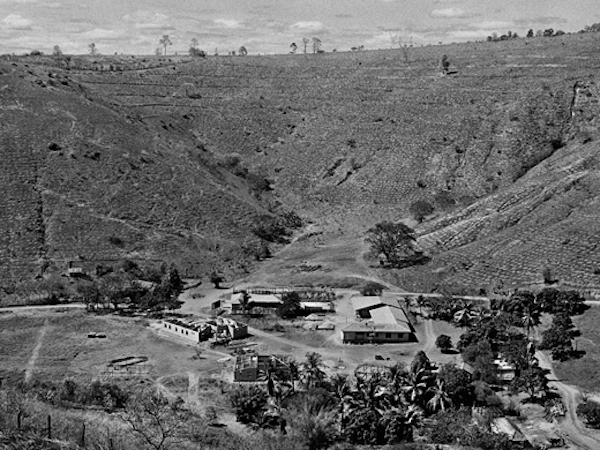

As always together with Lélia, they began his other great project: O Instituto Terra. The Brazilian coast, right from its origin, has been covered by an atlantic jungle — around 3,500 km inland — and the land belonging to Salgado’s parents once belonged to this ecosystem. Once political amnesty was reached, the couple decided to return to their country, but on arriving they found themselves having to deal with the issue of deforestation: the well-known perobás (a variety of oak) and other species of trees had been cut down, the fertile lands once covered in pasture had been destroyed, and the flow of water had been let loose on the area with no barriers in place, causing inundations. “Lélia said to me one day, Sebastião, let’s replant the trees” and without any botanical knowledge nor economic means, and feeling very much like city-people in a natural area they didn’t even live in, they bravely decided to embark the adventure. After six months they were involved in the replanting of 2.5m trees of the varieties found in the original jungle, and in the creation of the first Brazilian National Park located in a completely destroyed piece of land. Since then and to this day, the land belonging to his parents has been protected. And with the trees came the animals, such that his beloved childhood became a paradise once more, almost more beautiful than the one he remembered. This spectacle of the recreation of the circle of life was what made Salgado decide to capture with his camera the natural beauty of those places on earth where man has not yet set foot. “Genesis is my love letter to nature.”

O INSTITUTO TERRA, MINAS GERAIS, BRAZIL, in 2001, when the replanting of the Brazilian atlantic jungle began, and in 2013 having reached their goal.

“Photography is my life, it’s my way of living with meaning."

During the making of Genesis, Salgado transitioned from analog to digital photography. Between 2004 and 2008 he used Pentax 6458 cameras and medium format, 4.5 x 6.

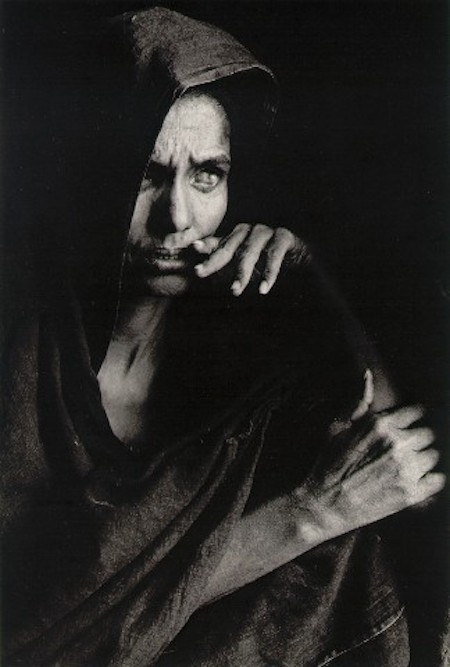

He uses monochrome with great dexterity, offering a whole new vision of black and white photography; the tonal variations of his work, the contrast between light and darkness, remind us of the Baroque period and of the works of the great masters of chiaroscuro, such as Rembrandt and Georges de La Tour.

In black and white we seek greater impact. When I was working in colour, the beauty of the blues and the reds seemed like they were erasing the emotion of what had been photographed. It diluted them. With black and white and all its range of greys, Salgado forces us to concentrate on the looks, the attitudes, and the density of the people: “When we see an image in black and white, it pierces us, we assimilate it and, subconsciously, we colour it.” For the photographer the moment of pressing down on the shutter release is unique and magical. Photography is the interpretation of a work in which various elements are linked together: people, the wind, the trees, light, the backgrounds… But in order to see the photography, the photographer must integrate completely with what is around him. It’s wonderful to read how Salgado describes those moments of bliss just before the shutter release: “You know you’re about to witness something unexpected. When you’re at one with the landscape, the moment, the image starts to construct itself in front of your eyes. In order to see it, though, you must be part of the process, and once you achieve this, all the elements start to work together with you… I love just sitting there for hours watching, framing, working deeply with light… You’ve got to love what you do.”

{youtube}nHJWgQxTous|600|450{/youtube}

To conclude, here’s an homage to two geniuses and their images.

Sebastião Salgado, Ciega a causa de las tormentas de arena (Blinded by the sandstorms), Mali, 1985. Pablo Picasso, Celestina.