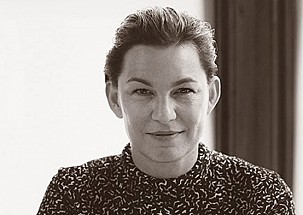

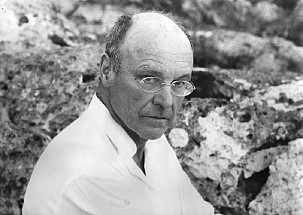

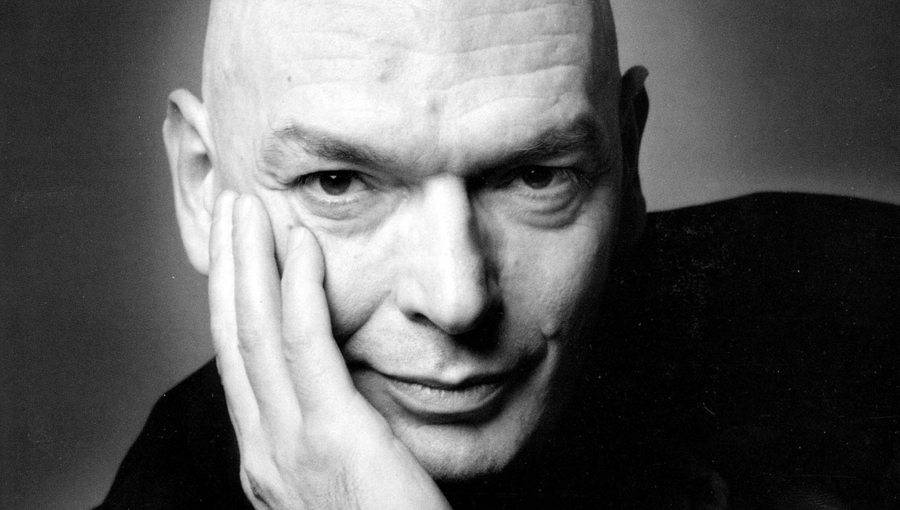

Architect Jean Nouvel Invites Us into His Creative Thought Process and Discusses His Current Battle over the Paris Philharmonic. >The Paris studio of architect, Jean Nouvel (b. 1945, Fumel, France), serves as the meeting place for our interview. Nouvel is one of the key members of an exclusive group of architects, which has been honored with the most significant architecture awards in the world, including The Imperial Prize of Japan, The RIBA Royal Gold Medal, The Pritzker Prize, The Aga Khan Award, and The Wolf Foundation Arts Prize.

Architect Jean Nouvel Invites Us into His Creative Thought Process and Discusses His Current Battle over the Paris Philharmonic

The Paris studio of architect, Jean Nouvel (b. 1945, Fumel, France), serves as the meeting place for our interview. Nouvel is one of the key members of an exclusive group of architects, which has been honored with the most significant architecture awards in the world, including The Imperial Prize of Japan, The RIBA Royal Gold Medal, The Pritzker Prize, The Aga Khan Award, and The Wolf Foundation Arts Prize.

Elena Cué: The anti-Le Corbusier architect Claude Parent was your mentor when you were starting out at the age of 21. Please tell me about what meeting him meant for your career.

You were actively involved in May 68 with a radical stance against the educational model of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. What were the things you demanded?

Jean Nouvel: I felt that his studio was one of the most creative at that time. He and his partner, Paul Virilio, created a space where a new approach to architecture could evolve. Paul became a very well-known philosopher and thinker of the time. I joined the intellectual rebellion of "May 68" and it certainly impacted my architectural style in terms of its criticism of the way in which French cities have traditionally been constructed. Later on, I joined with them to create the "March 1976 Movement," which demanded that the design of French cities no longer follow the same traditional model. Soon after, the architecture trade union was formed. It was a time of intellectual excitement.

EC: How would you define your architectural thought?

JN: I think it's similar to the solidification of a cultural experience, which means that ultimately, every generation has a job to do. Cities are made from an assortment of constructed testimonies, which reflect the things that each generation specifically liked, the different techniques that were used at that time, and their relationship with art. I've spent my life fighting against certain forms of academicism. It's true that there's an actual entity that's devoted to reproducing models from the past—the worst things from the worst situations and then making them pastiche. A pastiche, in reality, is always a degradation of what was true at an earlier time. It's like a ghost or a faint remnant of the past. I believe that every place deserves careful consideration.

In my opinion, every project is the start of an adventure, and clearly, I never seem to know where I'm going. I don't start with a preconceived idea. I always begin with a hope that the place, the experience, and the people with whom I am going to find myself at that moment are all going to contribute something completely unique. This sort of precision and nonconformity serve as an attack on the concept of cloning. Along these lines, there is something that has made the situation even worse—the development of information technology. Nowadays, the guidelines for creating any kind of project are readily available. As a result, you can design a building in a few hours based upon these predetermined criteria. It doesn't matter if they're residences, offices, or shopping malls. You select from what already exists, adjust a few elements, and just like that, it's done. Unfortunately, there isn't any gray area. There isn't enough thought, planning, or love in the designs that come about like that. They're automated and don't have any soul.

EC: In your work, as you say, you try to create a space that would be the mental extension of what is seen, a space of seduction, veiling and unveiling, looking and going unseen, concealing, light and shadow, mystery. How much is there of the erotic in your work?

JN: When there isn't mystery, there isn't seduction. Architecture is a mystery that must be preserved. If everything is revealed at once, nothing will ever happen organically. Without a doubt, concealing is one of the elements of eroticism and therefore, of erotic architecture. So, if we look at the Cartier Foundation, for example, you have two parallel, clear glass panels on a surface creating a mysterious uncertainty because of the way it plays with the reflections of the trees and the clouds.

There are also situations where you can play with the presence of nature to the point that you wonder if it's really a garden, for example. A garden is where thousands of natural species have reproduced and are coexisting together. All of these things, as well as the interference with the sun and the rain, create certain sensations that we aren't used to feeling. It's a form of simplicity that truly hides an enormous complexity and this complexity is what distinguishes that specific location. The reflections and the porosity of the emerald-colored glass make it so that you can hardly see what's behind. When you put blinds on the inside, it appears as if the landscape is printed on them.

Essentially, one attempts to choose ways of concealing, ways of showing, ways of hiding, ways of saying things or not saying things, and ways of suggesting things, but not ever formulating them. That is architectural eroticism.

EC: You work is highly heterogeneous, your buildings adapt to the space, context and culture with which they will coexist. For each project, in what factors do you seek your inspiration?

JN: In life and situations. I believe in situational architecture. Circumstances don't only relate to the actual place, but also to the aspects of an encounter or an appearance. In this regard, I'm considered a "situationist," but I don't think you can design a building just like that. A building isn't a sculpture and it typically doesn't change places. Some are relocated, but that's very rare and I feel like those situations are completely unpredictable. For that reason, we are always searching for anything that can impact a project and change it, which means that we must respond to lots of questions and concerns. You have to realize that architects are always considered to be incompetent and yet their work in and of itself must be highly competent. Every time I'm asked a question, I have to view it as if I'm coming from the opposite perspective and there are a lot of things I just don't know. For that reason, we are obligated to listen, to take into account, and to understand all aspects of the question at hand, every single time. Essentially, you must always combine the outside perspective with the inner viewpoint.

EC: So, what is your perspective?

JN: Mine is generally from the outside in. Sometimes it can be from the inside out, but that's rare. I'm always looking for exteriors. Someone that knows a location or a profession very well has inner vision. If you visit a city that you've never seen before, you're able to see things without noticing every single detail. Something quite poetic and pleasing can be emphasized, highlighted, and revisited by those who are on the inside. The architect's first task is what I call catalysis; in other words, it means to put things in their place. When the catalyst is present, things usually materialize with just a tiny spark. Then, there's the job of harmoniously combining all of those elements that, oftentimes, are contradictory. You must try to establish unity or synergy.

EC: The first time I met you, you were disappointed with the end-result of the enlargement of the Museo Reina Sofía. Can you explain what disappointed you?

JN: I wasn't happy. This often happens with me. Sometimes, contracts are not entirely clear and businesses have intentions that are not necessarily the same as ours. It's always been like that, but before, architects had a certain level of power that would get them respect in these kinds of situations. As time passed and the economy advanced, things became much more complicated, like how things are today. Perhaps, at the Reina Sofía, I wasn't happy about some of the conditions that were set forth in stone, but I'm generally not dissatisfied with the profound nature of the project. What bothered me most was that the Council promised to do a bunch of things. There was a study done by Álvaro Siza where the traffic in front of the Reina Sofía would be redirected underground. So, the project was carried out based upon the hypothesis that this would be accomplished. Well, what that means is that the pedestrians are not going to have the same relationship with the building and, further more, there is a sound effect caused by the noise from the street, which bounces off the roof and is heard inside where the original calmness has been lost forever. It's simply not possible to have the same tranquility that was originally envisioned

EC: You have commented that in your building for the Cartier Foundation you mix real and virtual images using glass panes and light to trick the senses. Your aesthetic principles are reminiscent of the artist James Turrel, who explores the perception of space by using light to modify that perception. Are you interested in this artist’s train of thought?

JN: I am really interested in Turrel. He's someone that works with light, nothingness, and location. He's an artist that completely plays with locations. His works simply can't be moved to different places. Their meaning derives entirely from their locations. I'm not talking about the core of the design, which obviously is very close to his vision of the world. I'm referring to the way in which his designs are positioned in order to frame the sky or to capture and create light thereby altering the classification and contours of the location. I really like artists that work according to the situation at hand rather than simply focusing on a few objects that they don't really know where to put. As a result of the commercialized advancement of art, I think that there's a kind of truth to art that is best expressed when the works are done in their original location. They either belong to a place architecturally well or geographically well. Needless to say, all of James Turrel's work involving perspective and light has clearly inspired me for a very long time.

EC: You've designed a lot of buildings in Spain. Which one of them did you enjoy the most?

JN: Because of what I've explained to you, I really don't want to tell you which one. What I can say is that I can't put the Agbar Tower in Madrid. It just wouldn't work. So, for example, people that don't know Barcelona see the Agbar Tower in international magazines and they don't understand it at all. The Agbar Tower is completely Catalonian. It simply can't exist in another location. Its formal design has been utilized by Catalonian architects for many centuries and was inspired by Monserrat's mountainous peaks, which have been shaped by the wind. The phallic nature of Monserrat's peaks is impressive. The fact that the Tower has been designed on an urban scale never seen before and that it's also colored makes it a tribute to Gaudí. The Catalonians and Barcelonians readily acknowledge that the building represents their culture and, at the same time, understand that it was formed from their DNA. On the other hand, the international community only sees the phallic symbol as a suggestion of sexual provocativeness and nothing more.

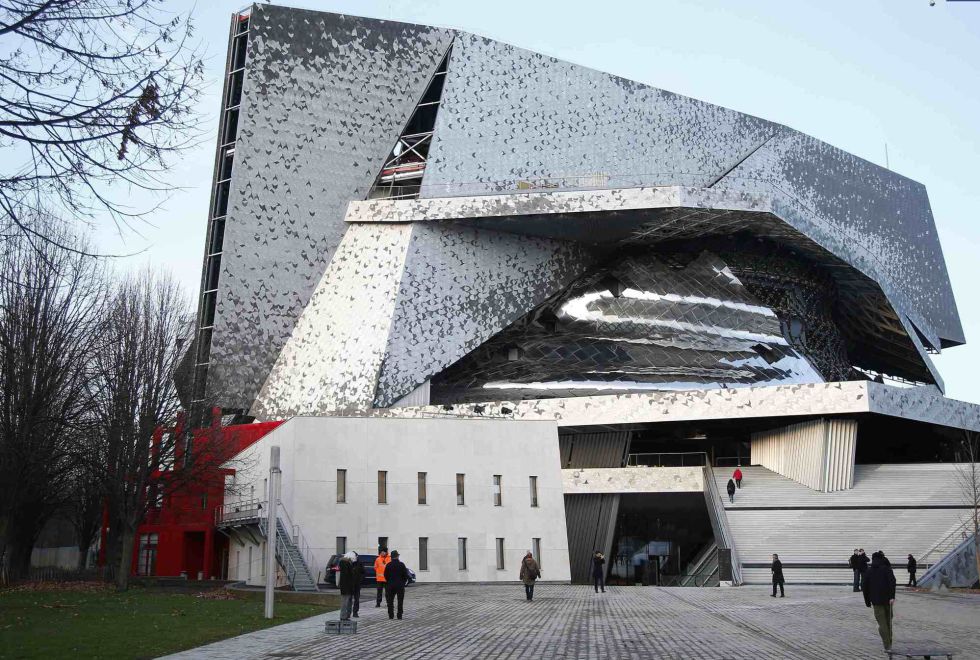

EC: The recently installed Paris Philharmonic opened to the public without your work being finished, and yet it's been an overwhelming success. What can you tell me about this project?

JN: The Philharmonic is a drama and a melodrama. It's the kind of project where normally, everything is in line for success. I feel that it's a project that demonstrates an innovative arrangement of a room on a musical level, a room that successfully defends the use of inside space as well as its emphasis on musical symbolism. Everyone recognizes that. Unfortunately, the building itself isn't finished, obviously. For political and financial reasons, they've done something that's never been done in France since all public buildings are made by a public entity that controls the use of funds. This project was carried out by a private association that decided to hide the rise in cost and, for that reason, they pushed me aside. All of this might seem rather tragic, but in my opinion, it doesn't really feel that way because I'm used to suffering when it comes to my profession. I'm here to defend the pleasure of all music lovers and the artistic aspirations that all of the children will have, thanks to this building. For that reason, I'm going to fight to the end in order to settle this so that the building is completed correctly and no one accuses me of any atrocities about the way in which it was finished, its details, or about the public spaces that surround it. I'm involved in one of the toughest battles of my life.