- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

It is difficult for personalities with such prolific lives as the doctor and French politician Bernard Kouchner (Avignon-1939) not to provoke admiration and controversy. His political life, apart from the legendary May of '68, developed through his ministerial positions in the governements of Mitterrand and Sarkozy, demonstrating his independence. Moreover, he has been a UN Special Representative and Head of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (1999-2001). He has also published numerous books, articles, and essays. But the most oustanding accomplishment is his humanitarian work started in 1968 when he traveled with the Red Cross to Biafra, Nigeria. This experience moved him very deeply, leading him to establish the non-governmental organization, Doctors Without Borders (1971), which made him worthy of winning the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize. In addition to this accomplishment, he was also the founder Doctors of the World (1980). Kouchner has been present since the beginning of many great natural and politial disaters in the world by assisting and alleviating the pain of the civilian victims of both wars and catastrophes.

E.C: We are flying over African territory, where everything started. What do you think the future holds for Africa?

B.K: Well, just a few words on the past of Africa: it has a past of battles and difficulties, but the group of people existed already and ISIS existed, although it was not as unethical… And when a colonisation came, all the colonisation, I mean the Portuguese, the Spanish, the French, the Indian, the British, they kept all the population in peace. And sometimes they cut families into parts. As ever, all the colonial lines were at the pressure of the battles, the armies, and after we used to say that we had to keep the countries like we were conquering them. I was not on a side but it was difficult. Sometimes it happened that we corrected the countries like it has been done between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Was it a good thing? I mean, trying to reproduce the borders of the people and the borders of colonisation? I don’t know, because Eritrea and Ethiopia are independent countries but they are fighting each other so I think that the old, wise decision to keep the border like it is - of course it’s an obstacle for the future, but it is like that, we cannot change completely now. So the future of Africa is certainly a big transformation, a big change, a big jump in the 21st century. First the population of Africa is important. We know that two billion will come in the coming century - before the end of the 21st century, so a very big potential for people. Will it be possible to educate them enough, because of the number of them? Yes, I hope it will be done by an international effort. This a huge continent, with space. For us - for Europe, we are all considering Africa like a free territory; like part of the future of humanity, that’s for sure. That’s why it was so important for the people of the bank - the bank of Dakar - to start in a country where democracy already existed. And Senegal is the best example of a democratic country in Africa. So it’s very important to start from a solid start, like in Senegal. Not all of the countries are looking like Senegal. We cannot answer to such a question, ‘yes, Africa is part of the future of humanity, it’s a continent in progress’ without a few words on terrorism and extreme Islamism. We have to fight against that, and today Nigeria is one of the most important countries in Africa. In Nigeria, business is developing, people are working very quickly. They have to take Boko Haram and the massacres of the women and the young people and the kidnapping, all this babarian attitude very seriously. And I hope it will be done by a sort of coalition of people. It will chat to Niger, etcetera. That’s very important also for the future. For their economical future and their political future. For the political with their particular forms, the future should be democratic. With an African style of course, an African conception of the word.

E.C: In 1979 you chartered a hospital ship, that was named Ile de Lumière, with a mandate of helping political refugees to run away from the communist regime of Vietnam in smalls boats. Do you think the Île de Lumière would be a utopia today given that thousands of Africans throw themselves to sea in search of a better future?

B.K: Yes. Formerly, we were talking about how, over the rest of the century, Africa is changing. But today, the most important question for them, and for us in a way, not the only one but an important question – is migration. What are we supposed to do, facing migration? First, we cannot stop the flood. It will take time, it will take years and years. Because the people there are not coming to us - to Europe for the pleasure of the country, they have to because of the poverty, the misery. They are fleeing out of misery. Out of misery, because there is no future – no immediate future – for their families. They have to feed their families. And in some countries like Mali, it is culturally necessary to leave and to go to France. And there are places where, if you’re arriving at the age of being an adult, you have to leave and find a job to send money back to your family. First point: they are not coming to please us, or to fight us. They are coming because misery is high, immense. Second, the TV representation for them, they believe that arriving in Europe they will find a job immediately and become rich, but this is not true. Because we are crossing a big crisis. And even in our country, unemployment is a big problem. So unemployment and migration, this is very difficult. We should nor confuse the « migrants « ,general speaking, and the asylum seekers. Those people leaving from a war, a dictatorship, those who cannot come back home without risking their life, being jailed or tortured should be accepted, along the terms of the Genova convention (1951). We are talking here about «economical migrants», not protected by Geneova Convention.

But first, we cannot mix even if it is impossible we cannot intellectually, in consideration of the people dying in the Mediterranean Sea. We cannot say ‘yes, but there are 11 migrants’, all migrants are fleeing for economical reasons and not political reasons. They are illegal, so we should rescue them. This is a moral obligation. This is very difficult to explain to the people and that’s why, as we are refusing massive migration, the people believe that we shouldn’t save the people. Some of them believe that we don’t have to send them a rescue belt or a rescue jacket. No, even if, after they come to Italy or to France or to Spain, we cannot just let them die. This is impossible for me. For me, even if we haven’t solved the problem of immigration in our country, we improve the number of people accessing our place. But two answers: first, we cannot say ‘we should think about a new general convention’ because the general convention obliges the countries to give asylum for political reasons if they cannot go back to their countries because of dictatorship, or because of racial attitudes. If it is too risky for them to go back, we have to give them asylum. This is the general convention, I think '54? And we are obliged, we signed the general convention. But the people, the migrants, the majority of them are coming because they are fleeing out of misery, as I told you. Not because of dictatorship, not all of them - Eritrea certainly. They are also fleeing for war reasons - the Syrian people, the Iraqi people. So it is very difficult just to separate now economical migration and political migration. First point: Europe exists. If Europe exists, this is not to let them die in the Mediterranean Sea. And I gave you the example already of the French boat: we sent seven of them to the China Sea – 12,000 km away, when the boat people were swimming to Vietnam. We were good to do so. The Mediterranean Sea is our sea: the sea of our culture, the sea of our holidays, the sea where we lie in the sun on a white beach. So we should rescue. Europe’s answer was very slow and it was an impossible, unfair and cold answer. We let them get on shore in Italy, the big majority. Of course, because Italy is the nearest country and the people are leaving from Libya and from that whole coast. Because of the commercialisation of slavery, all of these people, the migrants pay between one thousand dollars and seven to ten thousand dollars. All the efforts of their family during their whole life. And of course, these people, the merchants of slavery, they promise ‘you will find…’ etc. And they promise access to Great Britain across the channel, but no, it is impossible. So, the first answer should be coming from Europe – we have to share the burden, not to let them stay in Italy by thousands and thousands and ten thousands. No, we have to share the burden and we need to answer the proposal coming from the new commission - The Russell Commission. And this is absolutely no-one. The twenty-eight countries have to change. And the proper numbers – I remember from my country it was around seven thousand people. It is not so large! We are sixty-seven million now. So we have to share, all the twenty-eight countries. But they didn’t answer yes! They failed to listen. First answer: sharing in twenty-eight countries according to the number of people - the demographic, and second, the richness. So they did the calculation and then Jean-Claude Juncker proposed: first we have to rescue them. And not only the Italian boat and saying thank you to the Italian people and thank you to some of the Spanish people when they were coming from Libya and from Morocco etc. We cannot let them die. So let’s send one boat per country. Twenty-eight boats, this is nothing for the country. And if the country has no access to the seas they have to rent a boat! This is nothing. The second answer is sharing the burden, not letting the Italians accept all the numbers. And after, according to the Schengen Law, to cross the border and to be joining, say, Sweden, etc. That’s my answer. We should see this complicity of murder, not helping them in the sea, second, immigration is a problem. Do we have to change with a new answer of the general convention? I think so, it will be very difficult, but we should do it.

E.C: You named ISIS. What do you think is the future of ISIS?

B.K: To make a long story short, I think that we will get a new state somewhere between Syrian territory and Iraqi territory, because they already suppress the colonies at the borders. It’s up to the local population to fight against them, like the Kurds did. And I’m very confident with the Kurdish way of fighting against Daish. But we, and this is a must, should help the Kurdish people to fight against Daish. We tried - the Americans more than us - but we tried. We were involved in Iraq, we were involved everywhere, but it was not a big success. The poor Americans, they lost all the wars! Vietnam, Afghanistan and, of course, Iraq. So this is not a solution for us - to send ground troops - certainly not. Not ground troops, at the moment.

But if there were a real invasion, the answer of bombing the country like the Saudis did in Yemen, was another failure. They were killing the population more than the soldiers. We have to consider the internal battle between Shiite and Sunni people. Daish is now, unfortunately for the victims, killing Muslim people. Even if the danger is a world danger, they are killing Muslim people, so the Muslims they should react - with our help. But their future? I don’t know. I think there is no future for people as brutal as they are. I was very impressed when I went to Syria a few months ago to see a Kurdish woman fighting as a commander-in-chief in the city of Kobane. She was the commander of a thousand men and women, and they resisted to Daish, and they won! With a bit of help from the French people, and much more massively from the American people. We’ll see, I think that Bashar from Syria will not resist any more, I think that he will be replaced by another. The problem is Iran also fighting against Daish. Iran is a Shiite country fighting against ISIS - Sunni people, and this is a vicious circle. But we are exactly the way we were with the fighting and aggression against the protesters. This is a repetition. Don’t believe that religion is made for peace, religion is also made for war. I’ve no precise answer, but I believe that ISIS will lose. But immediately they will gain a big territory.

E.C: In 1971 , from "Doctors without Borders" you became a strong advocate of the concept of humanitarian intervention in order to protect civilian population from a sovereign state in countries which were unprotected and faced civil war, famine or genocide. Do you think this has been effective? What areas do you think could be improved?

B.K: Sometimes it has been effective. Like in Kosovo and Bosnia. Sometimes it has been negative, like in Iraq. We convince the UN system to vote in favour of the French resolution on the right to intervene. Because the right to intervene, according to my experience, was necessary to prevent war. But we never succeeded in preventing, except in Macedonia. In Macedonia in the middle of the Balkan war, we sent just a few hundred, and mainly Americans. We stopped the fighting, it was mainly by prevention. But for the rest, it’s always too late when we intervene, it’s always after the massacre. So I think that with the future of the right to interfere in protecting the people against massacre, unfortunately we were always waiting for the massacres and then we reacted. It was not always successful, not at all. Is Libya a good intervention? To protect Benghazi, the second city of Libya, against Gaddafi’s violent bombing by tanks, the right to protect the population is not binding and living at all. We had to have an agreement with the borders, and to stay and aid the people, with the agreement of the UN system. The right to interfere should go through the Security Council. Without a world agreement, any agreement is always coming from the only respectful international body, which is the UN. So I think there is a future for that if we are able to tell the people there is a risk of massacre somewhere, let’s try to stop the fire first. This is very, very difficult. Otherwise, we will be witnesses of massacres everywhere. Was it possible to protect the people in Iraq? Yes, it was the first success to get Saddam Hussein out. But after that, Shiite were the majority in Iraq, so Maliki was chosen after Allawi, who was elected as a secular guy. Maliki used the Shiism to get revenge on the Sunnis, so another time where it was not a good example. Is there a good dictator? This is a false question. Because of course it appeared, for the people, to calm down the situation, but it will not work for eternity. But was it better? My answer is no, but the answer of some is, ‘look, people were much more happy with the dictatorship’. The eternal question: For a doctor, and don’t forget that we were medical doctors. Medical doctors cannot accept massacres, just cannot. But that’s why, for me, the humanitarian conception is always a bit political. Protecting the people is political and of course, the humanitarian access is difficult. My answer is: Yes we have to protect, yes we have to act by prevention and, yes we have to act by information and education.

E.C: Did you achive more for human rights using your political platform or through your humanitarian work?

B.K: I think that it’s very complex to balance any inference of so-called political things. Human rights are political, and it will take years and years to explain to the people that the solution to the massacres is not hanging people or firing guns. There is no future for ISIS. Meanwhile there’s a sort of inside terror, and if you’re accepting terror, can you survive? At the beginning, yes, but after time you cannot. There is also no future for that. I’m in favour of human rights; I’m in favour of having respect for human life. I agree that religion as a peace process can work, but religion as a fight against the other religion, no. So we invented the right to intervene as a sort of medical dommage, but also as a political dommage. Medical passports were necessary to access the people at risk, to access the victims. Was it enough? No. But without a political vision it was impossible to force the door. Medical sensibility was affected by human rights; medical access was additional. Was it a political angle? Yes. Was it clearly political? No! This is impossible. Is it political dommage to save the people in the sea? No! This is a human dommage. And the right to interfere was a human intervention, for human victims. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than before, like some Jan Volski from the Polish government before the Second World War. He came to Churchill, Roosevelt having gone into an extermination camp and told them: ‘they are killing systematically’. But they did not intervene, they did not even bomb the railway going to Auschwitz. Why? Tell me why? For the same reason that we didn’t intervene for two years in the Mediterranean Sea. I don’t want to compare this directly to the migrants, but we still did not intervene. So, this is always a political decision. But the political decision is helped by sensible human reasons, by respect for human life. Who is respecting more human lives than a medical doctor? So it is an attitude.

E.C: You could be described as similar to the Dr. Schweitzer, the Doctor who attended to the sick in Africa and received the Nobel Peace Price in 1952. His motivations were to give back everything he received whilst he could. Is this your case? What are your motivations? Or perhaps you would describe yourself as “life-affirming" and a person who spreads vital values.

B.K: Well, I was writing a book on Schweitzer, he is a very interesting guy - the pioneer of this human access. Not for the same reasons that we had, he was a religious man. He was a protestant and a medical doctor. I’d say yes, he was one of our examples, and a good example. Of course at the same time it was before the discovery of antibiotics, and a lot people were angry because he didn’t use modern medicine. But at the same time it was good, he used the cultural methods of the people in Gabon. Of course, I visited his office in Lambaréné and sat at his table and I had a lot of admiration. My book on him is not finished, but Schweitzer gave us a good example for the time, and the time was a colonial time.

E.C: But what about your motivations?

B.K: My motivations are of course similar, but it was after the Second World War and after the Holocaust. And as I told you, nobody reacted against the Holocaust. When I was in Biafra, during the Nigerian-Biafran War, I saw the people coming to our hospital by the hundreds and hundreds. The bombing was targeting the civilian population. There was a blockade, so starvation was killing the babies in the thousands. So we were doctors, we had to react and protest, which we did and created Doctors Without Borders - just a few of us. I have to name my co-founder who was Max Recamier, he was not a political guy at all. He was a man of faith, he was a Catholic. But he was a doctor, so we did it together. It was more or less the same motivation but for me, it was more that my grandparents died in Auschwitz. And nobody protested. It was another time, but Schweitzer was a good example, not the perfect example – because there is no perfect example.

E.C: Do you think there is a solution to the Israeli conflict?

B.K: Yes, the solution is the creation of a Palestinian state. It is easy! But will it be possible? I cannot simply summarise, I don’t know if it’s completely too late. But the security of the Israeli is the security of the Palestinian. The Palestinian state would protect Israel; Israel would protect the Palestinian state. This is so obvious that it is ridiculous to find another solution. There is no other solution. Yes, for the time being the Israeli army is stronger than the other. But it will not last forever. So the solution is in between. I don’t say that the solution for Iraq or Iran is easy to say. But the creation of a Palestinian state is the beginning of all the solutions. We are in a real hurry. Unfortunately, for me, the Israeli people voted for Netanyahu. But my friends Tzipi Livni and Isaac Herzog - the chiefs of the Israeli Labor Party, were in favour of the Palestinian state, and they were right. So, on the other side, Mahmoud Abbas is an old man now. The new generation really want a Palestinian state, they are recognising Israeli people. Not only that, but they are meeting with them every day. This is ridiculous – it is a big, big crime not to recognize a Palestinian state. I know the story of Israel, yes they have the right to live, the right to be protected. This is my solution, that’s all. At the same time it is very difficult to understand the American political attitude to this. But President Obama wants to sign a document with Iran. I cannot be against peace; it is better than war. Let us see. For Israel it is a danger if Iran is following the line of setting up a nuclear weapon. I think to sign - if it is signed - at the end of the month, or at the beginning of July, I think that will be progress. Gaza was unacceptable, it did not change anything for some thousands of days of alienation. I know Hamas is not for peace, but I know that PLO is for peace. Let’s side with PLO!

E.C: What did you think about the position of Netanyahu?

B.K: Netanyahu was against the peace. Netanyahu is in favour of enlarging the borders in favour of settlement. We were close to the agreement with the former government, very close. I’m strongly in favour of the existence of the Israeli state, strongly in favour. But the basis of the Palestinian state is showing that they are not the country undermining Israel, not at all.

E.C: You’ve just arrived from Ukraine. What were you doing there?

B.K: I don’t know if I will do it, but I was in charge of offering a plan for changing the health system completely in Ukraine, like it was in Soviet Union and in Russia - a statist plan. I think we should mix public and private involvement under certain laws and under private health insurance, under public supervision. We’ll see, but there is a problem with Mr. Putin, who was not responsible for the separation between Russia and Ukraine, that was Gorbachev and Yeltsin. So we have to respect the border, and even if Russia is a bit different, the way they took over in fighting and bombing, remember, not only were they fighting but they missiled a Malaysian plane with Dutch people on board. It is not acceptable. I don’t know, we have a problem, and the solution is not war against Russia, certainly not. So is it sanctioning - economical sanctions? Partly, yes. And talk and talk, as we used to say, diplomacy.

E.C: What are your future proyects? Maybe a book? About...

B.K: I want to take some time to think about – and this is very arrogant of me to say so - my experience in mixing the political and the humanitarian. Having confidence in people but at the same time discovering that people love war. It’s like the most exciting experience for them, like a permanent merging and mixing male hormone through history, and though it’s a kind of caricature what I’m telling you, maybe it’s true. But I strongly think that you cannot separate humanitarian intervention from politics. I want the political people to be a more humanitarian, and I want the humanitarian to be more political. But they want to separate, you know why? Because of power! Having big NGOs gives you power. We are not all like Bill Gates, he’s a good example. I don’t want to insist too much, but remember what I said in your first question about developing Africa. Developing, developing; investing, investing. That’s the answer instead of letting them die in the sea, absolutely. We take tiny steps to start, we are starting with humanitarian, but humanitarian is not the solution of development, it’s a sort of generosity and charity. Okay, this is better than letting them die, but this is not the solution, the solution is development. So that’s why I was happy to be in Dakar for the setting up of the Dakar Bank, the people were waiting for that. It was a good signal in the modernization of Africa. So, we’ll see, because the solution is not to be a doctor instead of them or inventing the drugs in order to sell at high prices.

E.C: Could you tell me more about how Doctors Without Borders originated?

B.K: We were coming, young European doctors. French doctors. That’s why we went, we were French doctors and we were coming from a rich country; a country where we had been highly educated and we were had diplomas and we were working in hospitals, good hospitals, in France. And we discovered what? The reality of the world. And we discovered that our education was unable then to tell us what we have to do…what we had to do. What was our behaviour? We discovered that there were people dying of starvation, they were dying of misery. Of course they were also dying from bombs. We discovered a word: bomb. They were bombing the villagers, they were machine gunning all the highways, and they targeted the children. Every day there were violations of human rights, of course it was a civil war. So what were we supposed to do? To take care of the victims. OK, we took care of the victims from the bombing. It was not easy. A lot were dying, the others we tried to save. We played the role of doctors. Women and children, dying from bombing, okay, we helped. But after, we discovered that they were coming because of starvation, the children. We didn’t know about ‘Kwachmaco’ and ‘Marasmas’. The name of these illnesses were unknown to us real doctors. So the first time we set up a resuscitation unit for the children, so we tried to resuscitate them. Sometimes we succeeded. But then we had another hospital and then were was a flood of starvation they went back, resuscitated, to their villages. Then three months after, they came back another time with a different condition and the third time they all died. So what were we supposed to do? To say, ‘well, you know, we’re doctors and they came – doctors are waiting for the patients. First step: we went to the patients, across the border - across-the-border-doctors, doctors without borders. Then we protested politically. It was a big revolution because the doctors used to keep quiet. No, now it was not possible, the Hippocratic Oath is something between the patient and the doctor. Yes, you have to maintain ‘the secret’, but not during the massacres and it reminded me that during the Holocaust nobody protested. So we had to protest because the children – African black children were condemned because of the food blockade on both sides. There was a part of Nigeria completely at siege - that was our discovery. That’s why, coming back from Africa, we set up in ’71 because we were in ’68 and we had to regroup the people etc. We were obliged as doctors to play our role to exercise our duty. Our work. To be able to be a real doctor, we had, politically, to protest. Because there is always a way. They were dying from starvation, not because of natural disaster, because of a blockade by demand.

- Interview with Bernard Kouchner flying over Africa - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

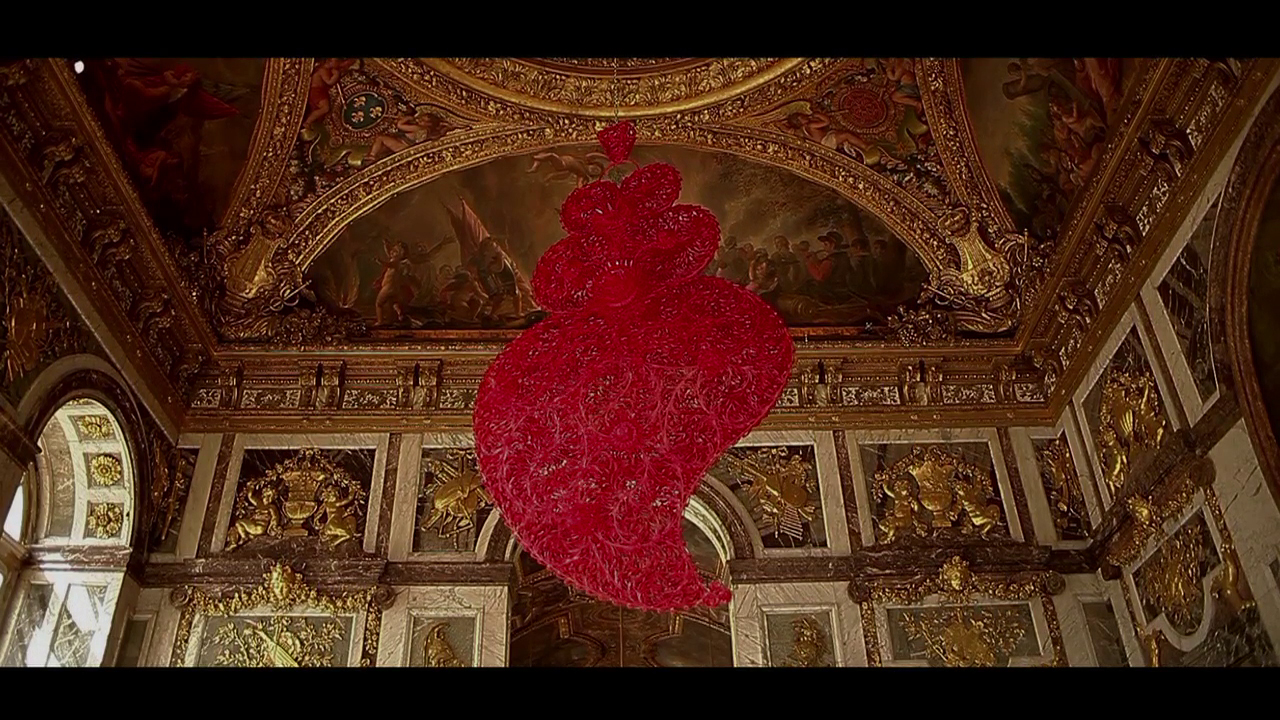

Joana Vasconcelos: "Artists manage to open a new path to beauty". The Portuguese creator conquered Moscow, Venice, Versailles ... where 1,600,000 people visited her exhibition.

In Lisbon, on the banks of the Tagus, is the studio where the artist Joana Vasconcelos (Paris, 1971) deploys all of her creativity. With her I made a tour through the technology rooms, the foundry, architecture and sewing rooms of the world of this Portuguese artist who conquered Versailles.

Elena Cué: Her birth in Paris was a result of the asylum her parents asked for in France when they escaped from the Salazar dictatorship. What configured the presence and affirmation of her roots and identity in her work?

Joana Vasconcelos: The fact that I am a Portuguese artist today is the political outcome of the dictatorship that conditioned many people in Portugal and Spain. My parents were in France and I was born there and the truth is that their life would have remained in France if there had not been the Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos). I think they would have stayed there and today I would be a French artist. Internet allows the artist to live in their country and to export their work without problems. People reflect their identity, but not only where they come from but also where they are; in other words, the artists can exist in their countries. This allows a person like me, a Portuguese woman, to be in Portugal. It's like another view of art.

What can you tell me about your childhood that has been important in your work?

My childhood was very normal, like all children. What I did that was different was karate for many years. It taught me to be very demanding, to achieve a level of results; it has to do with doing one thing from beginning to end. High competition workouts are very demanding. If we apply this to art, I would say that when I face a challenge or an order, I feel as if I were in a championship, I have to train to get a result. I could have made a career in karate, but there was a time when I wanted to go to art school, and I did both activities together. But after a week in Arco, I went for training session and broke my knee. That was when I understood that I could not continue in karate but that I could use all this training as an artist.

You are an artist committed to human rights and, in particular, the role of women in our society. What do you want to convey with your work, what dialogue are you seeking?

It depends on the work. I'm an artist, we do not think like men. I can be talking about the rights of women but also about beauty, the East, and the piece I did for Macao. It is another concept that has nothing to do with political things, it has to do more with the idea of beauty, volume ... I can be talking about communication. Women are like that, they can do many things at the same time, men can not. Men have a more linear discourse, it is another way of thinking, neither better nor worse, just different. We are like that. It is no longer necessary to have a single discourse.

What has it meant for you to display in Versailles?

I can not answer without telling you two or three things. I am the result of a time, of identities, of a change in the way we look at the world. Versailles could not have happened without first doing the Venice Biennale in 2005 with Rosa Martinez and Maria Corral, because they were in fact the first women at the Venice Biennale and both Spanish. I was the first woman in the Rosa Martinez exhibition and the world realized that I existed as an artist and I am very grateful. I was with Maria Corral in Venice and we said that there are people who are at historic moments and do not realise. This was my case in 2005. Then I did more things that led me to Versailles. In 2005 the world realized I existed but I had no works. Then I did a couple of exhibitions. One of them, in the Garage in Moscow, which was the first group contemporary art exhibition, and I was part of it. It was also a very important moment. Then I did another in the Palazzo Grassi in Venice and was there in front of all the big names: Struth, Jeff Koons, Murakami ... And again I had the chance, much younger and female, to be amidst a group of awesome people. Then I was invited to give an exhibition in Versailles. It would never have been possible if I had not done these international exhibitions where your work is alongside all these great artists of the world, where you have a presence.

You engage in a dialogue between past and present. When do you think that the great change in art takes place?

You were asking me what Versailles meant for me. Versailles changed everything. The exhibition had 1,600,000 visitors. Why? First, I am Portuguese. Second, I do not have a large gallery. Third, I have no great curator behind me. Fourth, no one knows me. 1,600,000 visitors! Jeff Koons had 850,000, Murakami roughly the same and you wonder, why? The truth is that the impact is greater for a woman, and I am also European.

You are closer to our culture ...

It's a culture that I understand, that we share in Europe. I integrated my work, I didn’t confront it with the palace. There was a divine union between the work and the space.

The great beauty of Versailles. Where does beauty lie in art for you?

For me art has to be beautiful. I believe that beauty and art are synonymous. I do not think it resides, I believe it is.

That moment when subject and object are the same ...

Yes. I think very much about the time, the emotion, the intensity ... I believe very much in the truth, in the idea that there are no lies, that communication is direct and sincere. If you look at these pieces they are not hidden, they are not isolated from the visitor, they are here present. And then you have many laws of understanding, you can look for this or that, but the truth is that they are hidden behind a theory. Then you can generate your own, but you do not need theory to exist. Beauty does not need theory, beauty is.

The big question, what is the concept of art for Joana Vasconcelos?

I think that art is what we are describing. It is the ability to generate a dimension of beauty and new light, that is, to me it is more interesting to talk about works than artists because those who are artists are the ones who manage, through one or many works, it depends, to open a new way for beauty, for understanding the world and to have a new perspective on the world. Art is the need to represent ourselves in complete freedom, art is the ability to keep the world alive, to keep our construction as human beings alive. This is why 1,600,000 people visited my exhibition because I represented Europe in a natural way. And when you are in a crisis it is more important that the artist should be in your country and represent your culture because otherwise, as in the Palaeolithic, you do not know what happened to the tribe that did not do the drawing, you know about the one that did. I not only represent my country but also this idea of common culture that we create in Europe.

I remember our first meeting in Venice. The connection between Lisbon and Venice through a ferry turned into a work of art after being covered by its wool, fabrics and crochet and the famous Portuguese tiles was an amazing experience.

Yes, the boat was the most complex and difficult project I had ever done. It took us a year. We did not have much budget either and the truth is that my country helped me, companies and individuals sent me money and it ended up being a movement of support to get me to Venice. It is at times of crisis when people want to have a say, when they want to be represented and not lose their identity. It was a national project. I had to reflect what Lisbon is today, which elements are specific to our identity, like the tiles, what we have in common with Venice, like the boats, the river, the fact that we are two tourist cities, the fact that in the 15th century we were strongly connected. There is a historical connection but also a contemporary one. For me, the connection was the water, for Lisbon and Venice water has complete control over the city. Then I took the boat and we transformed it. It was an amazing life experience. It is possible to do everything you think. It was sincere because people realize and help you. We must continue representing ourselves in the world. I came to Venice because the Portuguese wanted to come and I'm very grateful. It was all tough, the transport, the opening ... but we managed.

- Interview with Joana Vasconcelos by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

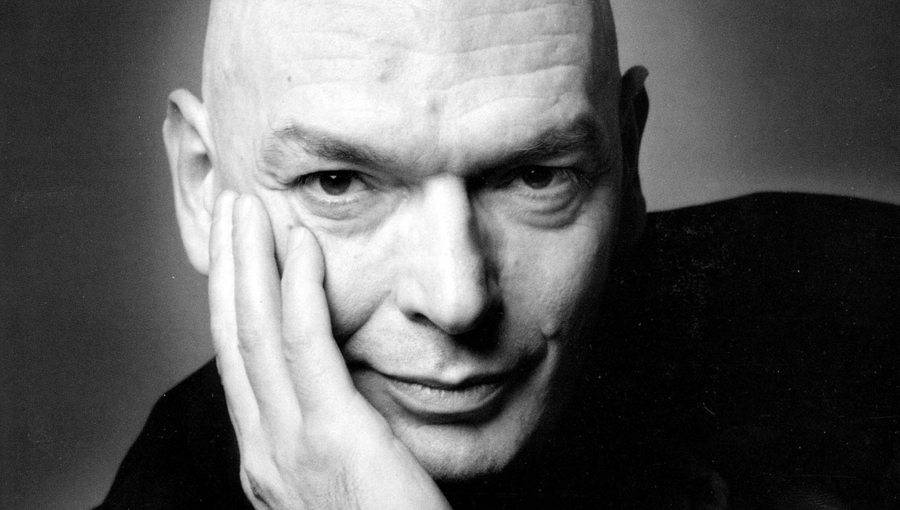

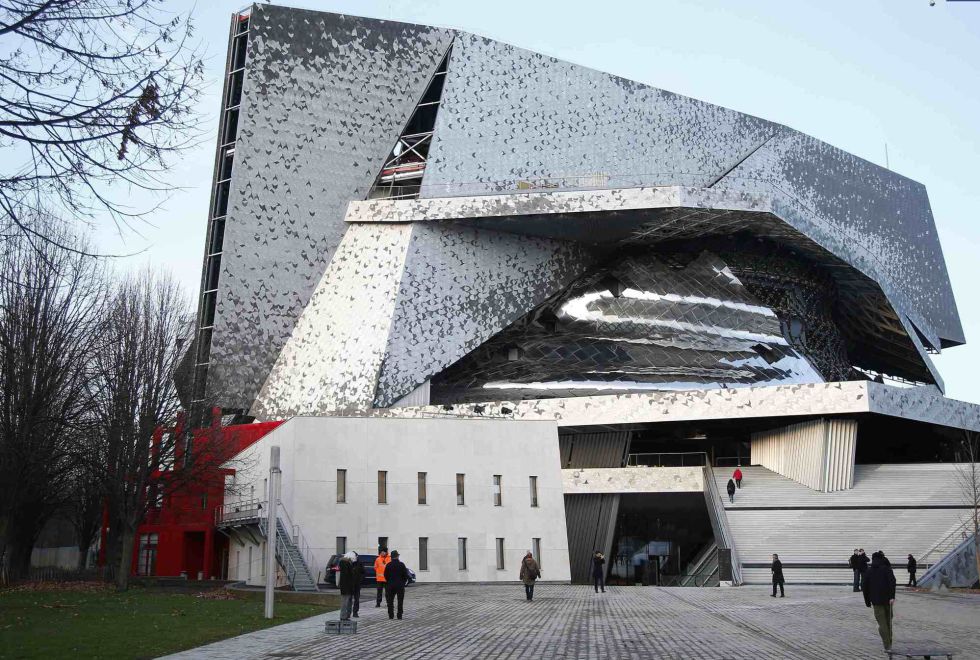

Architect Jean Nouvel Invites Us into His Creative Thought Process and Discusses His Current Battle over the Paris Philharmonic. >The Paris studio of architect, Jean Nouvel (b. 1945, Fumel, France), serves as the meeting place for our interview. Nouvel is one of the key members of an exclusive group of architects, which has been honored with the most significant architecture awards in the world, including The Imperial Prize of Japan, The RIBA Royal Gold Medal, The Pritzker Prize, The Aga Khan Award, and The Wolf Foundation Arts Prize.

Architect Jean Nouvel Invites Us into His Creative Thought Process and Discusses His Current Battle over the Paris Philharmonic

The Paris studio of architect, Jean Nouvel (b. 1945, Fumel, France), serves as the meeting place for our interview. Nouvel is one of the key members of an exclusive group of architects, which has been honored with the most significant architecture awards in the world, including The Imperial Prize of Japan, The RIBA Royal Gold Medal, The Pritzker Prize, The Aga Khan Award, and The Wolf Foundation Arts Prize.

Elena Cué: The anti-Le Corbusier architect Claude Parent was your mentor when you were starting out at the age of 21. Please tell me about what meeting him meant for your career.

You were actively involved in May 68 with a radical stance against the educational model of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. What were the things you demanded?

Jean Nouvel: I felt that his studio was one of the most creative at that time. He and his partner, Paul Virilio, created a space where a new approach to architecture could evolve. Paul became a very well-known philosopher and thinker of the time. I joined the intellectual rebellion of "May 68" and it certainly impacted my architectural style in terms of its criticism of the way in which French cities have traditionally been constructed. Later on, I joined with them to create the "March 1976 Movement," which demanded that the design of French cities no longer follow the same traditional model. Soon after, the architecture trade union was formed. It was a time of intellectual excitement.

EC: How would you define your architectural thought?

JN: I think it's similar to the solidification of a cultural experience, which means that ultimately, every generation has a job to do. Cities are made from an assortment of constructed testimonies, which reflect the things that each generation specifically liked, the different techniques that were used at that time, and their relationship with art. I've spent my life fighting against certain forms of academicism. It's true that there's an actual entity that's devoted to reproducing models from the past—the worst things from the worst situations and then making them pastiche. A pastiche, in reality, is always a degradation of what was true at an earlier time. It's like a ghost or a faint remnant of the past. I believe that every place deserves careful consideration.

In my opinion, every project is the start of an adventure, and clearly, I never seem to know where I'm going. I don't start with a preconceived idea. I always begin with a hope that the place, the experience, and the people with whom I am going to find myself at that moment are all going to contribute something completely unique. This sort of precision and nonconformity serve as an attack on the concept of cloning. Along these lines, there is something that has made the situation even worse—the development of information technology. Nowadays, the guidelines for creating any kind of project are readily available. As a result, you can design a building in a few hours based upon these predetermined criteria. It doesn't matter if they're residences, offices, or shopping malls. You select from what already exists, adjust a few elements, and just like that, it's done. Unfortunately, there isn't any gray area. There isn't enough thought, planning, or love in the designs that come about like that. They're automated and don't have any soul.

EC: In your work, as you say, you try to create a space that would be the mental extension of what is seen, a space of seduction, veiling and unveiling, looking and going unseen, concealing, light and shadow, mystery. How much is there of the erotic in your work?

JN: When there isn't mystery, there isn't seduction. Architecture is a mystery that must be preserved. If everything is revealed at once, nothing will ever happen organically. Without a doubt, concealing is one of the elements of eroticism and therefore, of erotic architecture. So, if we look at the Cartier Foundation, for example, you have two parallel, clear glass panels on a surface creating a mysterious uncertainty because of the way it plays with the reflections of the trees and the clouds.

There are also situations where you can play with the presence of nature to the point that you wonder if it's really a garden, for example. A garden is where thousands of natural species have reproduced and are coexisting together. All of these things, as well as the interference with the sun and the rain, create certain sensations that we aren't used to feeling. It's a form of simplicity that truly hides an enormous complexity and this complexity is what distinguishes that specific location. The reflections and the porosity of the emerald-colored glass make it so that you can hardly see what's behind. When you put blinds on the inside, it appears as if the landscape is printed on them.

Essentially, one attempts to choose ways of concealing, ways of showing, ways of hiding, ways of saying things or not saying things, and ways of suggesting things, but not ever formulating them. That is architectural eroticism.

EC: You work is highly heterogeneous, your buildings adapt to the space, context and culture with which they will coexist. For each project, in what factors do you seek your inspiration?

JN: In life and situations. I believe in situational architecture. Circumstances don't only relate to the actual place, but also to the aspects of an encounter or an appearance. In this regard, I'm considered a "situationist," but I don't think you can design a building just like that. A building isn't a sculpture and it typically doesn't change places. Some are relocated, but that's very rare and I feel like those situations are completely unpredictable. For that reason, we are always searching for anything that can impact a project and change it, which means that we must respond to lots of questions and concerns. You have to realize that architects are always considered to be incompetent and yet their work in and of itself must be highly competent. Every time I'm asked a question, I have to view it as if I'm coming from the opposite perspective and there are a lot of things I just don't know. For that reason, we are obligated to listen, to take into account, and to understand all aspects of the question at hand, every single time. Essentially, you must always combine the outside perspective with the inner viewpoint.

EC: So, what is your perspective?

JN: Mine is generally from the outside in. Sometimes it can be from the inside out, but that's rare. I'm always looking for exteriors. Someone that knows a location or a profession very well has inner vision. If you visit a city that you've never seen before, you're able to see things without noticing every single detail. Something quite poetic and pleasing can be emphasized, highlighted, and revisited by those who are on the inside. The architect's first task is what I call catalysis; in other words, it means to put things in their place. When the catalyst is present, things usually materialize with just a tiny spark. Then, there's the job of harmoniously combining all of those elements that, oftentimes, are contradictory. You must try to establish unity or synergy.

EC: The first time I met you, you were disappointed with the end-result of the enlargement of the Museo Reina Sofía. Can you explain what disappointed you?

JN: I wasn't happy. This often happens with me. Sometimes, contracts are not entirely clear and businesses have intentions that are not necessarily the same as ours. It's always been like that, but before, architects had a certain level of power that would get them respect in these kinds of situations. As time passed and the economy advanced, things became much more complicated, like how things are today. Perhaps, at the Reina Sofía, I wasn't happy about some of the conditions that were set forth in stone, but I'm generally not dissatisfied with the profound nature of the project. What bothered me most was that the Council promised to do a bunch of things. There was a study done by Álvaro Siza where the traffic in front of the Reina Sofía would be redirected underground. So, the project was carried out based upon the hypothesis that this would be accomplished. Well, what that means is that the pedestrians are not going to have the same relationship with the building and, further more, there is a sound effect caused by the noise from the street, which bounces off the roof and is heard inside where the original calmness has been lost forever. It's simply not possible to have the same tranquility that was originally envisioned

EC: You have commented that in your building for the Cartier Foundation you mix real and virtual images using glass panes and light to trick the senses. Your aesthetic principles are reminiscent of the artist James Turrel, who explores the perception of space by using light to modify that perception. Are you interested in this artist’s train of thought?

JN: I am really interested in Turrel. He's someone that works with light, nothingness, and location. He's an artist that completely plays with locations. His works simply can't be moved to different places. Their meaning derives entirely from their locations. I'm not talking about the core of the design, which obviously is very close to his vision of the world. I'm referring to the way in which his designs are positioned in order to frame the sky or to capture and create light thereby altering the classification and contours of the location. I really like artists that work according to the situation at hand rather than simply focusing on a few objects that they don't really know where to put. As a result of the commercialized advancement of art, I think that there's a kind of truth to art that is best expressed when the works are done in their original location. They either belong to a place architecturally well or geographically well. Needless to say, all of James Turrel's work involving perspective and light has clearly inspired me for a very long time.

EC: You've designed a lot of buildings in Spain. Which one of them did you enjoy the most?

JN: Because of what I've explained to you, I really don't want to tell you which one. What I can say is that I can't put the Agbar Tower in Madrid. It just wouldn't work. So, for example, people that don't know Barcelona see the Agbar Tower in international magazines and they don't understand it at all. The Agbar Tower is completely Catalonian. It simply can't exist in another location. Its formal design has been utilized by Catalonian architects for many centuries and was inspired by Monserrat's mountainous peaks, which have been shaped by the wind. The phallic nature of Monserrat's peaks is impressive. The fact that the Tower has been designed on an urban scale never seen before and that it's also colored makes it a tribute to Gaudí. The Catalonians and Barcelonians readily acknowledge that the building represents their culture and, at the same time, understand that it was formed from their DNA. On the other hand, the international community only sees the phallic symbol as a suggestion of sexual provocativeness and nothing more.

EC: The recently installed Paris Philharmonic opened to the public without your work being finished, and yet it's been an overwhelming success. What can you tell me about this project?

JN: The Philharmonic is a drama and a melodrama. It's the kind of project where normally, everything is in line for success. I feel that it's a project that demonstrates an innovative arrangement of a room on a musical level, a room that successfully defends the use of inside space as well as its emphasis on musical symbolism. Everyone recognizes that. Unfortunately, the building itself isn't finished, obviously. For political and financial reasons, they've done something that's never been done in France since all public buildings are made by a public entity that controls the use of funds. This project was carried out by a private association that decided to hide the rise in cost and, for that reason, they pushed me aside. All of this might seem rather tragic, but in my opinion, it doesn't really feel that way because I'm used to suffering when it comes to my profession. I'm here to defend the pleasure of all music lovers and the artistic aspirations that all of the children will have, thanks to this building. For that reason, I'm going to fight to the end in order to settle this so that the building is completed correctly and no one accuses me of any atrocities about the way in which it was finished, its details, or about the public spaces that surround it. I'm involved in one of the toughest battles of my life.

- Interview with Jean Nouvel by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

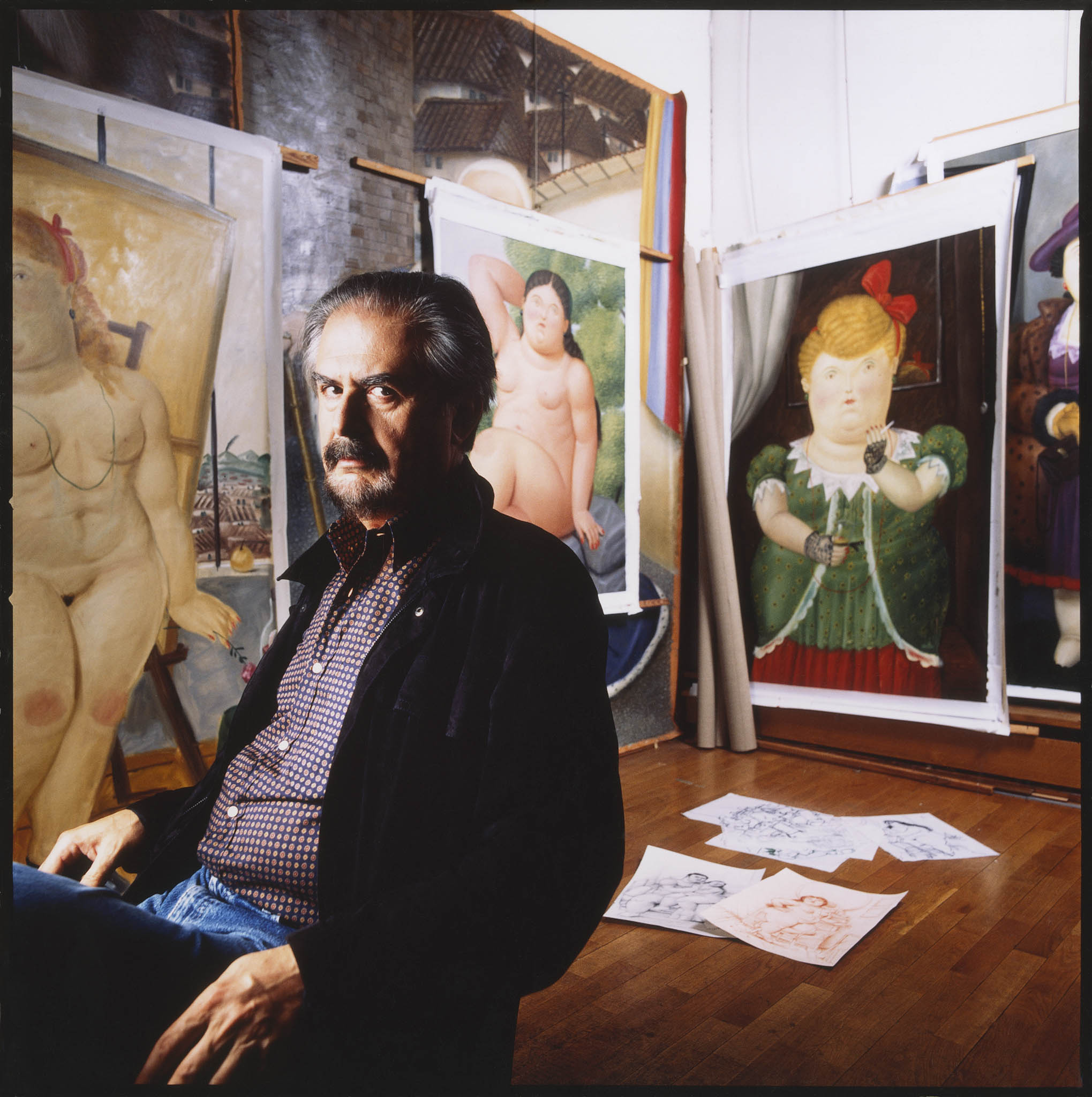

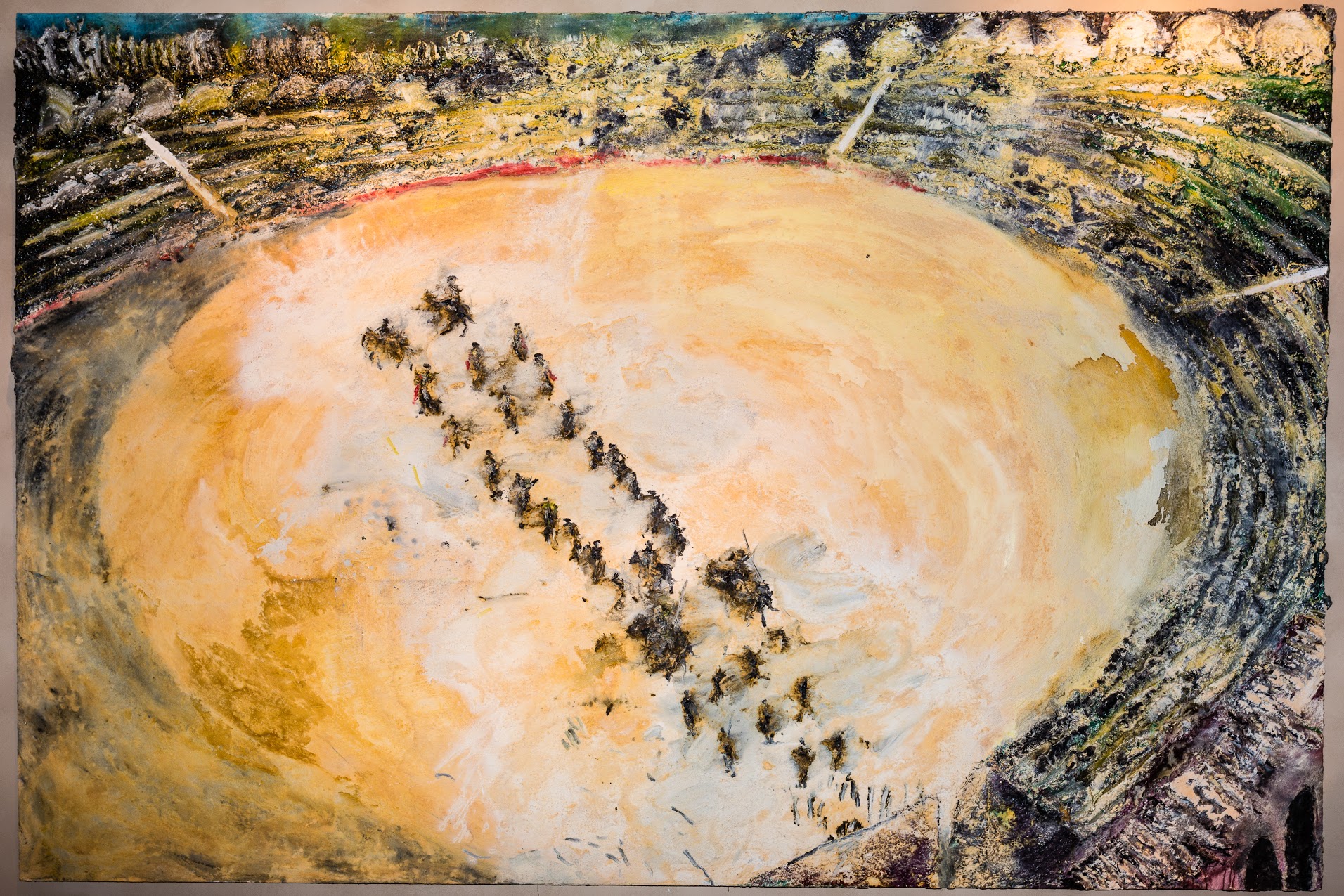

The international contemporary art fair, ArcoMadrid, will open its doors on February 25th, in association with Colombia, as an invited nation.

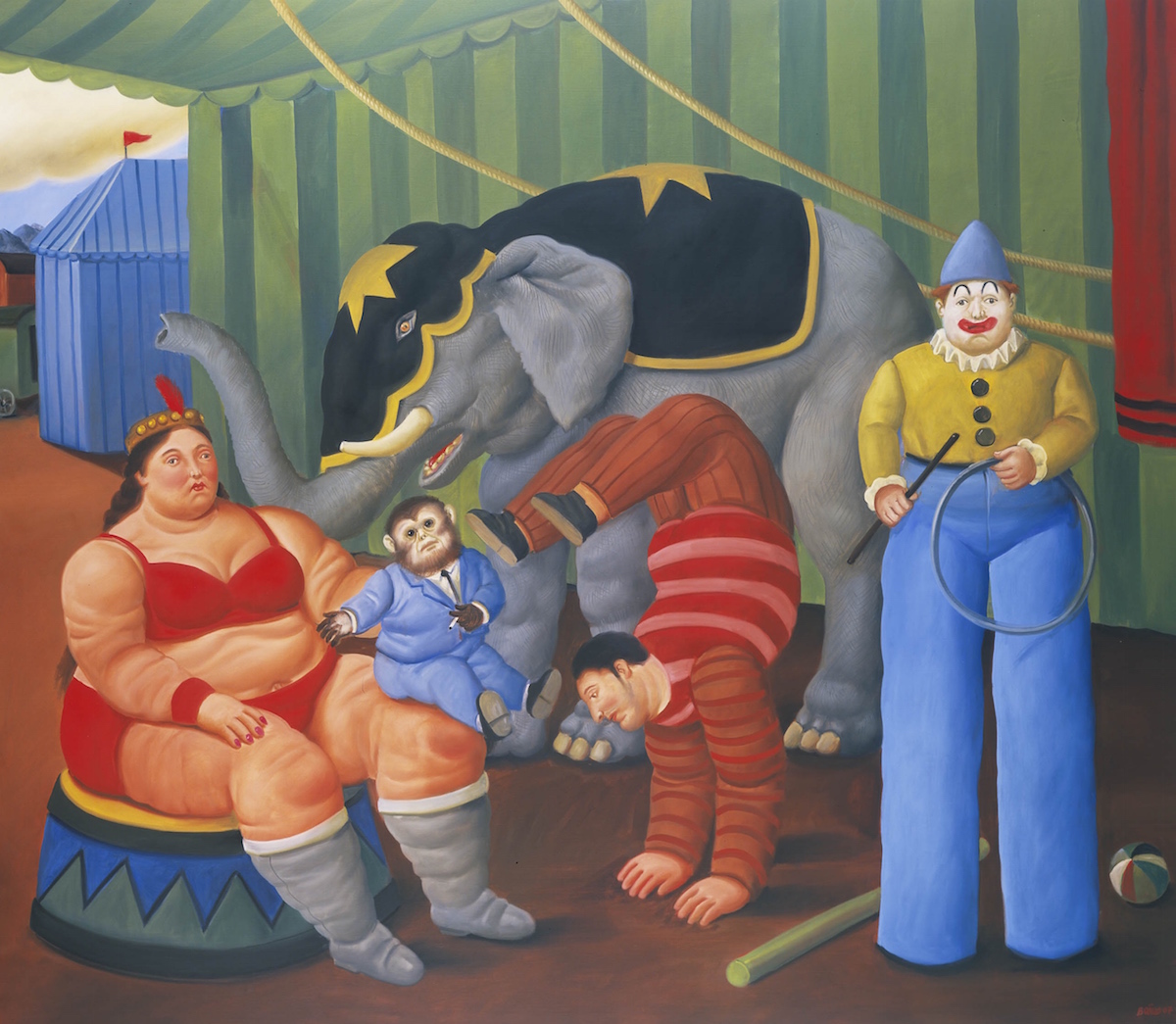

The Fernando Botero (Medellín, Colombia - 1932) art collection is one of the 50 most important museum collections in the world. As a palette, paint, and brush artist, his hands have never stopped working. His figurative art draws out the form and essence of his subjects, provoking a higher sense of sensuality, flexibility and grandeur. Reality is transformed through his imagination: sometimes into kindness, other times into scathing violence. The sculptures, paintings and drawings have created a relevant artistic production, whose objective is “to create a formal opulence.” These powerful figures, whether in marble or bronze, have been on exhibition in the most important venues in the world, such as: The Champs Elysees in Paris, Park Avenue in New York, The Grand Canal in Venice, and The Paseo de Recoletos in Madrid.

The still-lifes, the bull fighting, the circus, the religion and the eroticism make up an extensive theme rooted in Latin America — specifically in his native country — with a manifest skill in drawing and color. The beautiful and the violent combine together in the Boterian imagery that brings us closer to Colombia’ssoul through a nostalgic reminiscence.

Through his studies in Montecarlo, with views of the Mediterranean sea and his characteristic lighting, we can draw closer to the soul of this magnificent artist.

Elena Cué: His knowledge about art history is plentiful and has unquestionably influenced his art work. Do you believe that an artist can be complete without being influenced by culture?

Fernando Botero: A great artist is born from a profound knowledge of the tradition and problems of painting. However, there are many works in which freshness and audacity surprise, as can be seen in popular art and in certain examples of modern art.

E.C: You have said that “art is a permanent accusation.” Do you believe an artist has a moral duty to use his work to point out and denounce injustices in this devastating world?

F.B: The only duty an artist has is in the quality of the art. There is no moral obligation to denounce. An artist confronted with a tremendous injustice sometimes feels inclined to say something. Denouncing the situation is the artist’s choice.

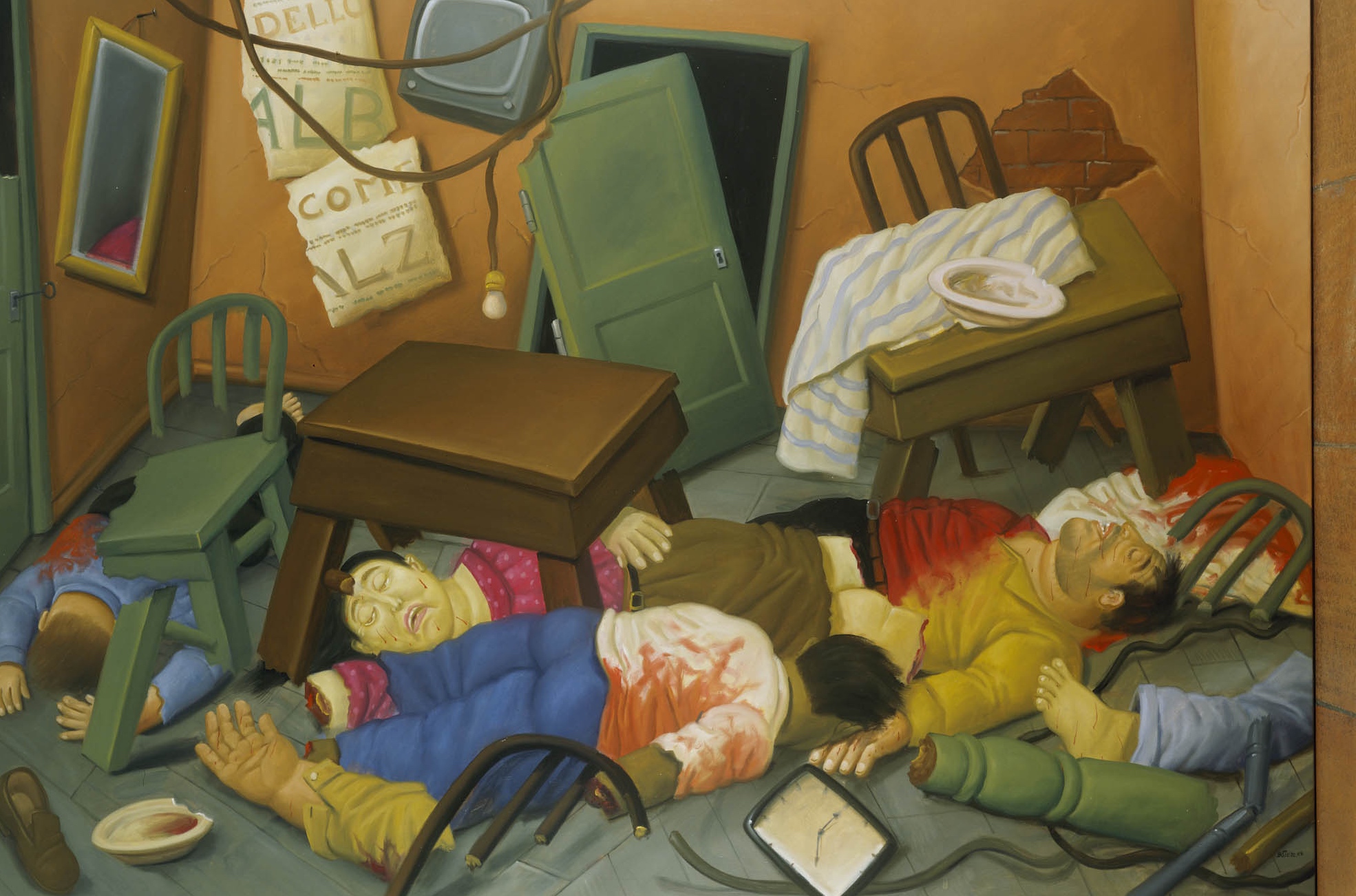

E.C: Goya’s influence in your paintings is evident. The series of engravings, “Casualties of War” ("Los desastres de la guerra") totally reveals a dramatic cruelty and barbaric humanity. Your work includes a series about the crimes that occurred in the Iraqi jail of Abu Ghraib after the United States attacks in 2001. In this world of cyber-technology, events are ephemeral, since the new always replaces the old, in contrast to art which is powerful and timeless, making it more applicable. Why did you choose this precise series of crimes?

F.B: I did not choose this series of crimes, it was impossible to ignore them: just like Iraqi prisoners being tortured by Americans, in the Abu Ghraib jail - the same place where Sadam Hussein was tortured. Or, the violence in Colombia which left thousands of victims, on both sides, and displaced people, and since this happened in my country, it was especially painful for me.

E.C: Goya already stated that illustration didn't make barbarism disappear. Do you believe there is hope in this respect?

F.B: It is not possible for art to resolve situations which are basically political. The artist shows the situation that exists like a “permanent denunciation.” Nobody would recall the small village, Guernica, which was bombed, if it were not for Picasso.

E.C: Wisdom comes from a long life. What do you believe is the meaning of life?

F.B: The meaning of life is different for everyone. Some take on a hedonist attitude. For others, there is a necessity for spiritual or cultural fulfillment based on discipline.

E.C: You have already embraced the life of an artist in every possible way, in all of its complexities. What counsel would you give the younger generations of artists?

F.B: An artist is born like a priest is born. If they are born an artist, I would tell them art is not a game, it is something very serious which completely requires everything you have to give.

E.C: With an aesthetic technique as identifiable as yours, in which reality is expressed through a volumetric sensuality, what opinion do you have of the English artist, Beryl Cook, whose work reflects a seemingly jovial nature with an aesthetic sense very similar to yours?

F.B: This is the first time I have heard of Beryl Cook.

E.C: Your artistic production has beentypecast as “Magic Realism” determined by the importance of the myths in Latin-America, as well as the “New Figurative”artcharacterized by a return to the informal methods of figurative painting. Do you agree with this description?

F.B: Magic Realism, definitely not, because in my works nothing is magic. I paint about things which are unlikely but not impossible. In my pieces, nobody flies and nothing impossible happens.

Art is always an exaggeration in some sense; in color, in form, even in theme, etc… but it has always been this way. It is the same with the nature of some works by Giotto or Massacio, or the color of life as expressed by Van Gogh.

It could be a new figurative work. It is probable because we have inherited the liberty from abstract art, and we have a liberty in terms of shapes. Color and space involves thinking, not realism.

E.C: What literature works have influenced and helped in the type of works you paint?

F.B: I do not believe that other arts can influence painting - sometimes a vulgar image or a piece of popular art have more affect in the sensitivity of the painter than a masterpiece of literature. Since the very beginning I intuitively had an interest in exaggerating sizes.

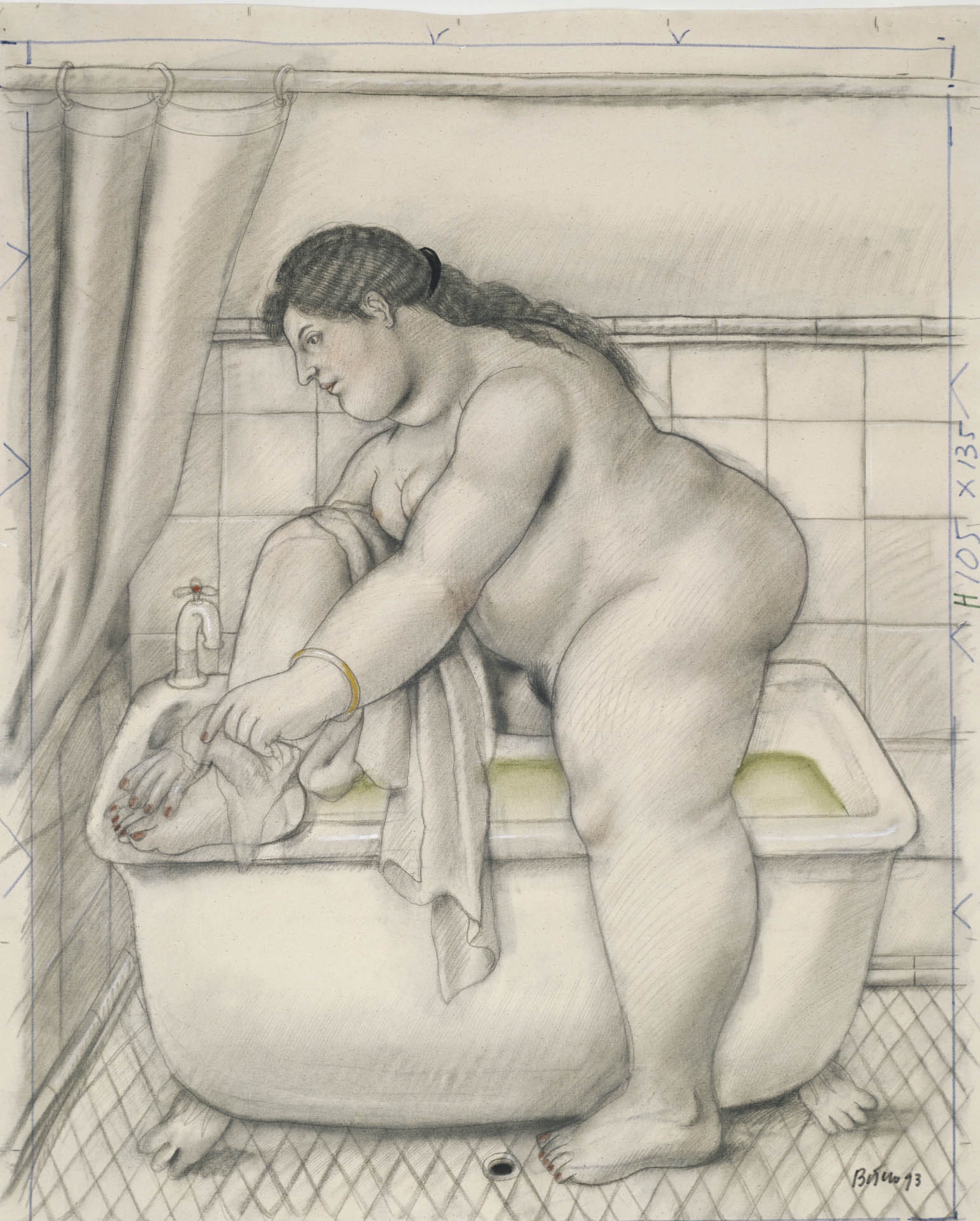

E.C: What importance does sketching have in your painting?

F.B: It is of utmost importance. Sketching is almost everything. It is the painter’s identity, his style, his conviction, and then color is just a gift to the drawing.

E.C: The generous donation of more than 200 works from your own collection to the Botero Museum in Bogotá, and almost 20 others to the Antioquía Museum in Medellín is exemplary.

What have your motivation and satisfaction been in this respect?

F.B: The donation I made to Columbia from my collection, and from many of my works, is one of the best ideas I ever had in my life. The public’s enjoyment is the best reward.

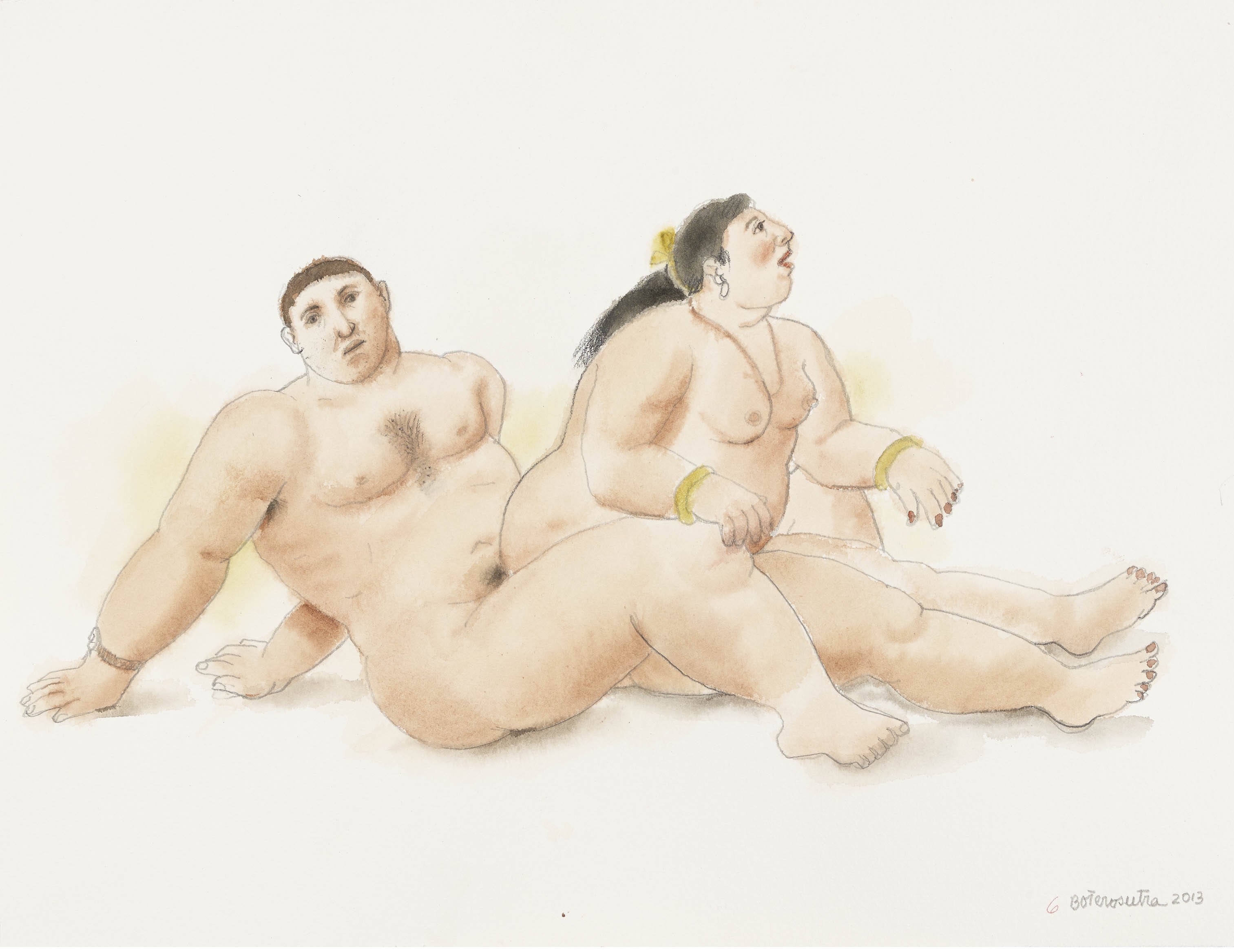

E.C: The millennial Hindu book, Kama Sutra, about the art of love in its spiritual and sexual fullness is reinvented by your imagination in Boterosutra. Which artists, from your point of view, have the best ability to represent love?

F.B: Eroticism has made great plastic manifestation all over the Orient, in Persia, Japan, India, etc. I did my Boterosutra series using more imagination than memory, trying as always to make the artistic expression more important than the theme - the rhythm of drawing, the subtle modeling, the application of color were the dominant elements in this series. The theme is extraordinary and unique because only in loving the human body can you make postures which could only be repeated in the circus.

E.C: Nietzsche, in The Birth of a Tragedy, writes “it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.” Is the art, as stated by Nietzsche, the metaphysical activity of life? For an artist like you, would this metaphysics be the only way we can make our avatars existence tolerable?

F.B: I have never read Nietzsche, but I do believe that the artist presents a world as the metaphysics of art. The artist presents, through his work in general, a more beautiful loving world that makes the “avatars of our existence,” as you said, more tolerable.

E.C: The study of the relationship of an artist’s biography and work has been a constant throughout the history of art. The Colombian history, social and political reality are expressed through your career. How do you see your country evolving right now? What vision do you have for spreading your national cultural identity?

F.B: The work of an artist, in its totality, is like a self portrait – in my country, in between great dramas, there has been an economic evolution and culturally positive advancements. I believe in the importance of the roots in an artist’s work. That ‘something’ that comes from the motherland is what gives works their touch of honesty.

E.C: What have been the most important moments of your life?

F.B: The most important moments of my life have always been connected to my work. They were moments in which I felt I accomplished something unexpected.

E.C: What do you have left to do?

F.B: Learn to paint.

- Interview with Fernando Botero by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

"No Comment" is the title for the opening of the exhibition of Chinese artist, Yan Pei Ming, at the Center for Contemporary Art in Málaga (CAC, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo).

Yan Pei Ming (b. 1960, Shanghai) grew up during the Maoist Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and worked as an artist to support the regime. Later on, he was part of the first group of artists to flee China in 1980. With great expectations, he arrived in France to study Fine Arts and earned a degree in that subject in Dijon, Paris and Rome. This geographical, cultural and artistic shift has had a substantial impact on his work.

The work of Yan Pei Ming stands out because of its decisively simple palette of red, white and black, and its forceful yet precise brushstroke line that sends us into his private world. His work primarily focuses on the portrait, an artistic genre that he depicts by emphasizing the psychological burden displayed by his iconic subjects. When you enter into the Parisian studio of this French-Chinese artist, you get the immediate sensation that you've not only traveled through the history of Western painting, but also that you've seen traces of the time period when he was working to support the Mao regime. All in all, Yan Pei Ming is, perhaps, one of the best examples of what it means today to be an artist in a global world -- where human beings, in a particularly dramatic way, are confronting experiences of solitude and death.

Elena Cué: You grew up in China in the midst of the Cultural Revolution and then relocated to France when you were 20 years old. You studied for five years at the National Superior School of Fine Arts in Dijon. What was the pictorial evolutionary process like going from the limitation of propagandist art to support the regime to complete freedom?

Yan Pei Ming: At that time in China, the influence on painting was from the classical tradition originating from the Soviet Union. It was propagandist painting to support the regime at that time. Those five years that I spent at the National Superior School of Fine Arts in Dijon were years of absolute freedom for me. From that moment on, I was able to combine what I learned from propagandist painting with a very individualized view of today's world. My freedom of expression is very noticeable in my current work.

E.C: How did you survive the East to West cultural shock, going from a communist regime to Mitterrand's Socialist France?

Y.P.M: In France, individuality was what stood out. In my opinion, the politics of François Mitterrand were, no doubt, socialist, but still liberal.

E.C: You graduated from the French Academy (Villa Medici) in Rome in 1993. What was your impression of Italy? What was that experience like?

Y.P.M: It was one-of-a-kind. I had an incredible year. It was as if I was in paradise, following the steps of all of the great painters that had come through this city. Those old masters help me to understand art from the past and they pave the way for me to make art that must be done nowadays. It was an unforgettable experience for me.

E.C: What memories do you have from childhood?

Y.P.M: My childhood was blessed, but lonely. Even from my earliest years, I was in my own universe. I always dreamed of being a painter because I could express myself without words. That's powerful.

E.C: You have painted your father several times, even dead. Tell me about him, please.

Y.P.M: I have always done portraits of my father, just as much in China as in France. I have captured him at different times in his life, and at different ages. My way of seeing him has evolved over the years. Also, there are oftentimes characteristics and defects that I've been able to find in the titles of those portraits. It's true that the way in which a child sees his father is not the same way an adult sees an older parent. I think that my portraits of him bring that to light.

E.C: You have depicted Mao on several occasions. What does that mean and who is Mao, in your opinion?

Y.P.M: He has been present in my work since I was a boy. His was the most copied and most widespread image in China. That left a mark on me. I also remember that my first lesson at school was entitled, Long Live President Mao! He is a mythical character.

E.C: Your 2009 exhibition, "The Funerals of Mona Lisa," made you the first Chinese artist to exhibit at the Louvre Museum. A huge portrait of Mona Lisa was accompanied by four paintings: two self-portraits depicting skulls from the cranium scanner, a portrait of your dead father and a self-portrait in which you pretend to be dying, which tops off the exhibition. Why is Mona Lisa crying? Can you explain this peculiar scene?

Y.P.M: It is a piece that I did in 2009 for the Louvre. It is a polyptych called, "The Funerals of Mona Lisa." I reinterpreted Leonardo da Vinci's portrait to be Mona Lisa crying at her own funeral and in front of spectators. My expression is similar to that of Marcel Duchamp after adding a few whiskers.

E.C: Your existential concern began at a very young age. The ongoing presence of death in your thinking is constantly represented in your work. Does the idea of death make you reaffirm life?

Y.P.M: A lot of emotional states appear in my work: my anxiety, my pain, my uncertainty. It is important for death to be present as well -- and, of course, energy and life. I don't need to sugarcoat or make things fancy. Paintings aren't for cuddling.

E.C: What worries you most about death?

Y.P.M: When I think about death, I rise up. From that point on, I work even harder to fill up on life. I'm not afraid of death. I'm afraid of no longer living.

E.C: Iconic paintings of art history and celebrities, your self-portraits and the representation of your father. Do you think that it is a way to transcend?

Y.P.M: I'm interested in everything, just as much art history as historical figures and the anonymous. The construction of history and sociopolitical issues interest me a lot. They all form our world as well as my painting.

E.C: Much of your work involves portraits, primarily figures, politicians or celebrities with sometimes serious and solemn expressions, yet kind and friendly other times. To what extent do portraits relate to the passing of time, as it does with Rembrandt?

Y.P.M: You're right. Rembrandt is a master portrait artist, especially the self-portrait. He's an important artist in my eyes. He's not the only one. There are also French, Italian and Spanish painters like Goya, El Greco, Velázquez and Picasso.

E.C: The revealing and fierce strength in your pictorial expression, combined with the huge sizes of the canvases and the drama of your simplified color palette of white and black or white and red really emphasize the emotional burden that's conveyed by those depicted. What are you most interested in drawing out from each character?

Y.P.M: In my opinion, the individual is the essence of humanity. A portrait allows the individual and their time period to be seen.

E.C: You stated on one occasion, "What interest me about a person are their attitudes, fears and lives, which are often tragic." Is the goal to feel less alone when facing one's fears and one's existence?

Y.P.M: I'd like the world to share my anxiety and my fears.

E.C: In your series on killers -- people that randomly snatch life away -- what is it that interests you about them?

Y.P.M: Animals have always fought to survive. I think that the same thing happens with man. Conflicts, wars and injustices are characteristic of man.

E.C: As an artist, where do you see beauty?

Y.P.M: To me, beauty is found in painting.

E.C: Your interest in Goya shows up in your reinterpretation of The Executions of May 3 or in Picasso, whom you've depicted. Have you been to the Prado Museum? What do you think of our Spanish masters?

Y.P.M: I've visited the Prado Museum several times and it has impressed me every time. When I was at art school in Dijon, one of my professors, Jaume Xifrá, made quite an impact on me. He was Catalan and spoke to me a lot about the Spanish painters.

E.C: Do you believe that there's a dividing line, or at least some difference between the Chinese artists that left China after the Cultural Revolution and those that stayed?

Y.P.M: There are differences between the artists that departed and those that remained. Without a doubt, their environments and lifestyles are different and therefore, their work is as well. In regards to myself, I would say that, as of today, I am a nomadic artist without borders. I am just an artist.

E.C: Your work deals with war and peace, money and globalization, capitalism and communism, with death as the backdrop. Is this your view of the world?

Y.P.M: My view of the world is pretty pessimistic. I don't believe in peace. Since the beginning of man, war has existed and it endures. It makes me think that man will continue fighting until the world is destroyed.

- Interview with Yan Pei Ming by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

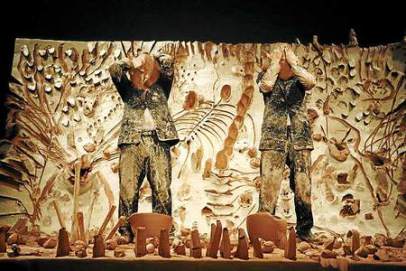

Yue Minjun (1962) is considered one of the most prominent Chinese artists of our time. He was born in the Heilongjiang province, situated in the North-East of China and belongs to a generation of artists who grew up in the midst of the the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). This was a decade marked by repression and fear, with education based on idealistic beliefs and principles. Intellectuals were sent to the countryside to work in order to learn about agriculture and production, contributing to the revolution through physical labour. With the death of Mao in 1976 came a period of reform and dramatically reduced repression, which saw an explosion of a new form of art. This emerged amidst many huge social, political and cultural changes, following an art form largely dictated by grandeur and political propaganda. The '80s are well-known for movements including '85 New Wave, which saw a surge of young artists breaking free from the recent past with a strong freedom of expression and creativity. The '90s, in turn, have been characterised by the emergence of Cynical Realism and Political Pop, and marked the beginning of the appearance of Chinese art internationally. Subsequently, the ‘noughties’ became a decade characterised by commercial success. Each of these factors have contributed to a transformation in the way of thinking and expressing art nowadays.

Elena Cué: Have these historical, largely outward changes been accompanied by similarly radical, internal changes for you?

Yue Minjun: Yes, that's right. My experiences, feelings and some things from my cultural past have been essential for my current artistic creation. Furthermore, these experiences have reaffirmed my artistic concepts. In general, the Chinese give the impression that we are calm and peaceful people, nothing eclectic or categorical.

E.C: How did the free art of your generation in the 80s and 90s errupt after the Maoist ruling?

Y.M: I started drawing at the age of 10, and, initially, during that learning process and the visual images of the time I was greatly affected in a different way to how I saw after the 80s. However, if you are an art lover, your interest will grow when you begin to understand why an artist paints in one way or another. Then, your interest grows into a deep curiosity and uses this as a tool to gain further knowledge, with a constant evolution towards personal growth.

Although a cultural and artistic system in China exists, with the introduction of foreign art the change was shocking.

E.C: What memories do you have from your childhood and what has influenced you?

Y.M: Many things have influenced me, especially from a visual perspective, because what I perceived in those days - or what I remember from them - have been transmitted to my painting as one of the most important factors of expression.

In fact, in many of my works we can trace influences of the origin of propaganda painting, which emphasises the influence of the Cultural Revolution in my memory. For example, there are rows of heads that appear one after another, that undoubtedly offered transcendence in my past.

E.C: He has been considered to belong to the Cynical Realism movement, first described by the critic Li Xianting in the '90s. This came about in response to the tragic consequences of the student and intellectual protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989. These resulted in Minjun moving to a colony of artists in Hongmiao, situated in the Chaoyang district on the outskirts of Beijing. In 1989, an exhibition here by Chinese artist Geng Jinay, depicting his own face laughing, influenced Minjun’s work. And in 1993, Minjuin too began to use representative self images in his work - capturing himself in a frozen moment of laughter. These faces have since remained in all of his work, becoming an unmistakable sign and trademark of his artistic identity.

Joking, irony, mockery, humour and pleasure… Laughter manages to lighten tragedy and pain, acting like a remedy against helplessness; like a safeguard against the imposed cruelties of reality on the sanctity of life; a clarity within solemnity; acting to undo the natural urge for power, that is Nietzsche's concept of a will to power. Laughter acts as an antidote to our anxieties and concerns, as a symbol of protest… Laughter is a powerful tool encompassing many meanings.

What does laughter represent for you?

Y.M: In my work, laughter is a representation of a state of helplessness, lack of strength and participation, with the absence of our rights that society has imposed on us. In short, life. It makes you feel obsolete, which is why, sometimes, you only have laughter as a revolutionary weapon to fight against cultural and human indifference.

E.C: Minjun's international recognition came in 1999 when he was selected alongside other artists to be part of a show directed by Harald Szeemann for the 48th Venice Biennial. This saw a series of sculptures used in clear reference to the Terracotta Army of Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of a United China; these are known as the warriors of Xian, with each of the warriors with a distinct face and identity. The individuals in your work are, by contrast, all smiling self-portraits.

Having grown up as part of a community, are you now using your work to try to empower the individual?

Y.M: Actually, the terracota army of Qin Shihuang Emperor, or The Warriors of Xi'an, are symbols representing feudalism. Then, the individuals are actually immersed within an expression of the army. Of course, if you look very closely, each one has a different expression; but if you reflect from a collective point of view, the image of each sculpture is projected more weakly.

Inspired by this historical work when I started to create my own sculptures, I trusted that using the same person and the same expression would portray the disappearance or absence of the individual more accurately.

E.C: Democritus, the Greek philosopher belonging to the pre-Socratic school of thought, was known as the "philosopher who laughs", owing to his knowledge that reality cannot be reversed and that laughter is the best tool we have to help us cope in life. On the one hand, this represents an accepting of our reality, thereby stripping it of all seriousness. On the other, however, this serves to help us make sense of our own existence.

Do you believe that man should use this as a weapon against the unintelligible nature of our existence?

Y.M: The laughter could be a perfect marriage with feeelings. If we have the capacity to smile throughout adversity, then our presence will become stronger, tolerant and diverse, both for the artistic culture and for the majority.

E.C: Some of Minjun's works use icons in reference to key works throughout the history of art, including Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix, The Third of May 1808 by Francisco de Goya, and the Execution of Emperor Maximilian by Manet, inspired by the Tiananmen protests.

To what extent has your work been influenced by Western painting? Does the laughter in your work represent any negativity or criticism?

Y.M: The influence was very big in the 80's, thanks to the reform and the opening up of China, it came to us with the impact of a variety of foreign cultures. At that time, I was studying painting and I had the opportunity to be in touch with these works, which is why external influences were so relevant to my artistic creation. In my evolving expression there is an important part of my old work that is evocative of realism, which, at the same time, examined important questions such as the revolution, social reforms, definitely, as well as passion for life. And then I was getting to know artists like Picasso, and I was approaching Western painting while reflecting on visual evolution.

I think representation like that, in a more popular and simple way, my works will generate a more comprehensive meaning, both for the Chinese and the Western viewer.

E.C: Do you use laughter as a tool for criticism in your work?

Y.M: Yes, that's right. That's why I choose to paint laughter, to comunicate a sense of pleasure and happiness, but actually, it hides a double perspective of drama and suffering.

E.C: What are your sources of inspiration and where does your aesthetic come from?

Y.M: Actually, my Western influences have not come in the form of aesthetics or techniques, but rather in the form of iconography. Ancient Western painters knew and used this form of enlightenment in their painting, which also have many different interpretations between the West and China. Therefore, I have also practised the use of iconography to portray the interpretation of what I actually want to express.

Regarding the aesthetics and techniques used in my work, one can appreciate a ceratin simplicity, referencing my training at University. A good example is my teacher, who graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts of China, learning the techniques of realism from the former Soviet Union, and France at that time. He also learned how to observe objects while influenced by Impressionism; he painted lights and shadows, etc. However, I make use of the techniques I learned through my work, no longer portraying spontaneity or thoughtlessness.

During the formation of my aesthetic style, beginning with my own feeling or point of view, I thought my work should be as simple as possible, without any handling; completely removing sophistication without altering the initial result. Actually, I claim that my work is directly perceptible, beautiful and candid, with bright colours in order to attract the immediate interest of the viewer.

E.C: At times you have said that each of your works are based on your feelings and experiences, and that you are by nature a pessimist.

Where does this pessimism come from and what has it led to?

Y.M: My pessimism comes from the sad desperation that I feel when I observe my own culture. I mean, the society that surrounds me, their way of life and my own.

E.C: Your works contain allusions to Communist iconography, to a consumer society or to historical moments, at the same time loaded with conceptualism. Tragedy and comedy are cleverly mixed in such a way that it makes it difficult for us to determine our feelings about what we are seeing.

How do you hope the public will approach your work?

Y.M: The direction of my work is allegorical between human nature and our own existence. Because I have noticed that, not only in the East or in China, people are constantly facing emotional conflict.

I want to show how the individual, through painting, must remain awake, and how we need a greater understanding of the basic concepts of nature and life itself.

My work dosen't try to overly dramatise, and not because of that absence of tragedy. I want to refer to what each person feels by their sorroundings, or to the past experience that has been left in them through materialism; this does not liberate the human spirit, it is a pressure that leads to slavery.