- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Florence, during the first decades of the fifteenth century, was the axis around which the world turned. In among its twenty neighbourhoods with their gonfaloniers, their streets and palaces, their churches and houses, Alberti was writing his treatise “On Painting”, Masaccio had painted the Brancacci Chapel frescoes and his Holy Trinity adorned Santa Maria Novella church, Ghiberti completed the North Door of the Baptistery and Brunelleschi crowned Florence cathedral with a dome which, using never-before-seen techniques, he made to float in its enormity above the Santa Maria del Fiore apse.

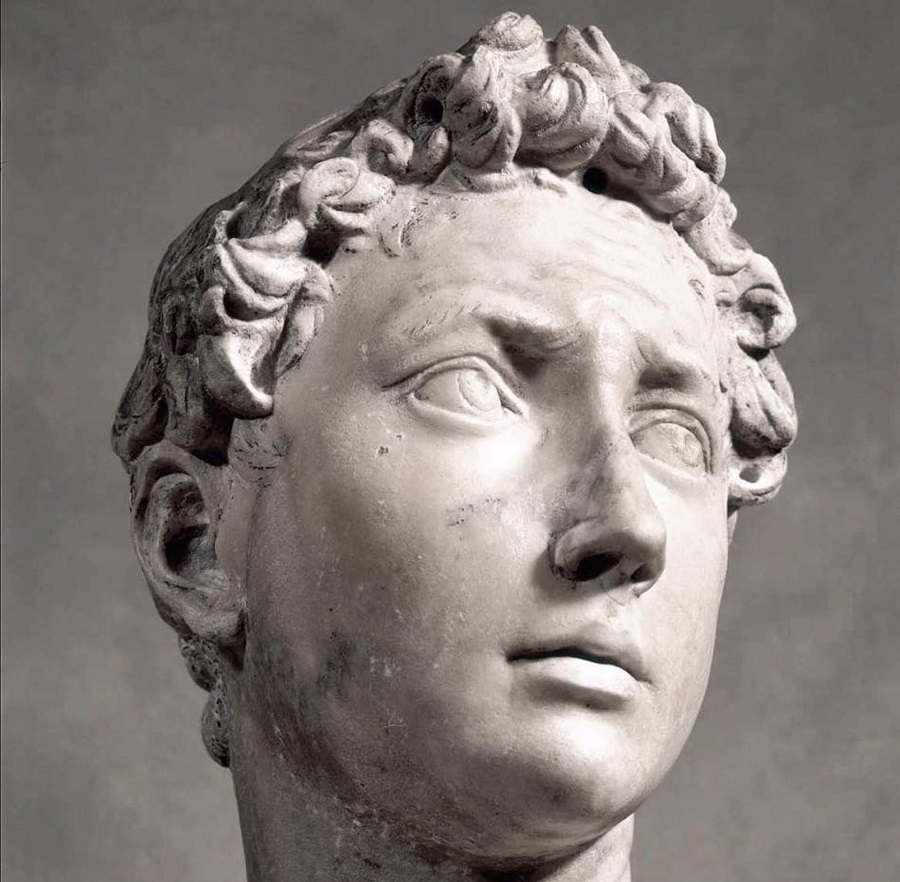

Donatello, David (detail, (1435-1440), National Museum of Bargello, Florence

Florence, during the first decades of the fifteenth century, was the axis around which the world turned. In among its twenty neighbourhoods with their gonfaloniers, their streets and palaces, their churches and houses, Alberti was writing his treatise “On Painting”, Masaccio had painted the Brancacci Chapel frescoes and his Holy Trinity adorned Santa Maria Novella church, Ghiberti completed the North Door of the Baptistery and Brunelleschi crowned Florence cathedral with a dome which, using never-before-seen techniques, he made to float in its enormity above the Santa Maria del Fiore apse. The year was 1436.

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

Meanwhile, in his small workshop on the banks of the Arno, Donatello sculpted the relief of the plinth of Saint George of Orsanmichele. His mastery was to forever revolutionize the principles of sculpture. Six hundred years later, Florence returns light to a world full of darkness with one hundred and thirty works on display throughout the Strozzi Palace and the National Museum of Bargello, in a historic and unrepeatable tribute to its sculptor son. The exhibition carries the name: Donatello, the Renaissance.

Donatello, Horse's Head (1456), National Museum of Archeology, Naples

Donato di Niccolo di Betto Bardi - Donatello being the nickname given him by his family - was born in Florence in 1386. The Donatello family lived on the south bank of the Arno river and were members, through Niccolò (father) and Betto (grandfather), of the wool carders’ guild, one of the most influential in Florentine society at the time. From an early age, he worked with a local goldsmith through whom he discovered metal alloys, while also learning how to sculpt from the stone carvers working on the construction of the Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral. In 1403, he entered the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti, a sculptor in bronze who had, the year before, won a competition to create the Gates of Paradise for the Baptistery. Donatello had collaborated with him and had since become friends with Filippo Brunelleschi with whom he travelled to Rome. Little is known about this trip except that, by aiding in the excavation of the ruins of the ancient Empire, Donatello acquired a profound understanding of the ornamentation and classical forms of Roman sculpture, movement, fabric and gesture. This apprenticeship, together with the tutorship of Ghiberti - the greatest exponent of an international Gothic style typified by smooth, curved lines - had a marked impact on the sculptor's style which would evolve into the life-size marble "David" that kickstarts the Florence exhibition today.

Donatello, David (1408-1416) National Museum of Bargello, Florence

The first room of the Strozzi Palace is breathtaking. "David" (1408), centre stage, was carved by Donatello in his early twenties. He had received a commission for a monumental figure of the King of Judea to form part of a row of statues to act as guardians of the Duomo, anchored atop the buttresses as if miraculously silhouetted against the sky. The work was completed by the end of the same year with all that remained being to lift it into place. As soon as the scaffolding was erected, however, it was found to be too small to create the desired impact. At that elevation, the six-foot high prophet statues looked insignificant. For this reason, the David was positioned in a new, unexpected and more worthy location. The figure of the young biblical hero, also one of the symbols of the Florentine Republic, was purchased by the government for its headquarters in the Palazzo della Signoria. Standing him on a pedestal at ground level proved to better highlight the slight twisting of the torso, the flexing of the leg and an oblique, frowning stare gazing into space. In this exhibition room, the enormous head of Goliath with a rock embedded in his forehead at David's feet is at eye level. And on looking up, we see two chilling crucifixes in painted wood flanking the statue of David. On the left, Donatello’s (1408) and on the right, Brunelleschi’s (1410).

First exhibition room: Donatello's "David" (1408)(centre), Donatello's Crucifix from the Basílica of Santa Croce, Florence (1408) (left) and Brunelleschi's Crucifix from Santa Maria Novella, Florence (1410) (right)

The sculptor’s outlook was maturing. His work was moving away from the Gothic tradition and towards a more personal, more solid style. The years from 1411 to 1413 saw a radical shift in his art that broke free with transformative force. Brunelleschi and Donatello spent hours observing the multiple panoramas and buildings of Florence. Brunelleschi was beginning to understand how geometric shapes underlie the relationship between humans and their environment. Donatello would convey these conclusions through the medium of sculpture. Both artists were luminaries in the discovery of perspective.

Donatello, Saint George (detail), c.1415-17, National Museum of Bargello, Florence

Donatello now began creating a brand new way of sculpting that he would apply for the first time to the “St George and the Dragon” in the predella panel of the Armaioli tabernacle in Orsanmichele Church and which he chiselled out using “soft stiacciato” (“flattened out”), as Vasari termed it. This technique involved the shallow carving of a relief whose depth and surface projection gradually increased towards the foreground where the figures and objects are closest and the most prominent. In the background, the shapes are just a few millimetres deep, hardly more than a slight incision.

From then onwards, he introduced the “stiacciato” method to his reliefs which were admired throughout Florence and paved the way for other sculptors, inlayers and painters. Brunelleschi's laws of perspective, applied using this technique, allowed the sculptor to virtually and optically multiply space with a hitherto unknown sensory illusion of reality, creating a revelation between the viewer and the work.

Donatello, Saint George and the Dragon (1416-1417), National Museum of Bargello, Florence

In the third room of the Strozzi Palace, behind the “Attis Amorino”, we find the bas-relief of “The Pazzi Madonna” (1422), chosen to be the poster for the exhibition. It is one of the most emotive interpretations of the Madonna and Child of the Renaissance. The mother, with a profile and veil reminiscent of Ancient Greece, holds her son in her arms and brushes her face against his in a gesture of intense sweetness. Her eyes, in which the tragic events at Calvary can be read, are fixed on those of the child she embraces with hands seemingly desperate to protect him. The child, oblivious, smiles showing his milk teeth and clutches his mother’s veil with total naturalness.

Donatello, Madonna Pazzi (1422), Staatliche Museum, Berlin

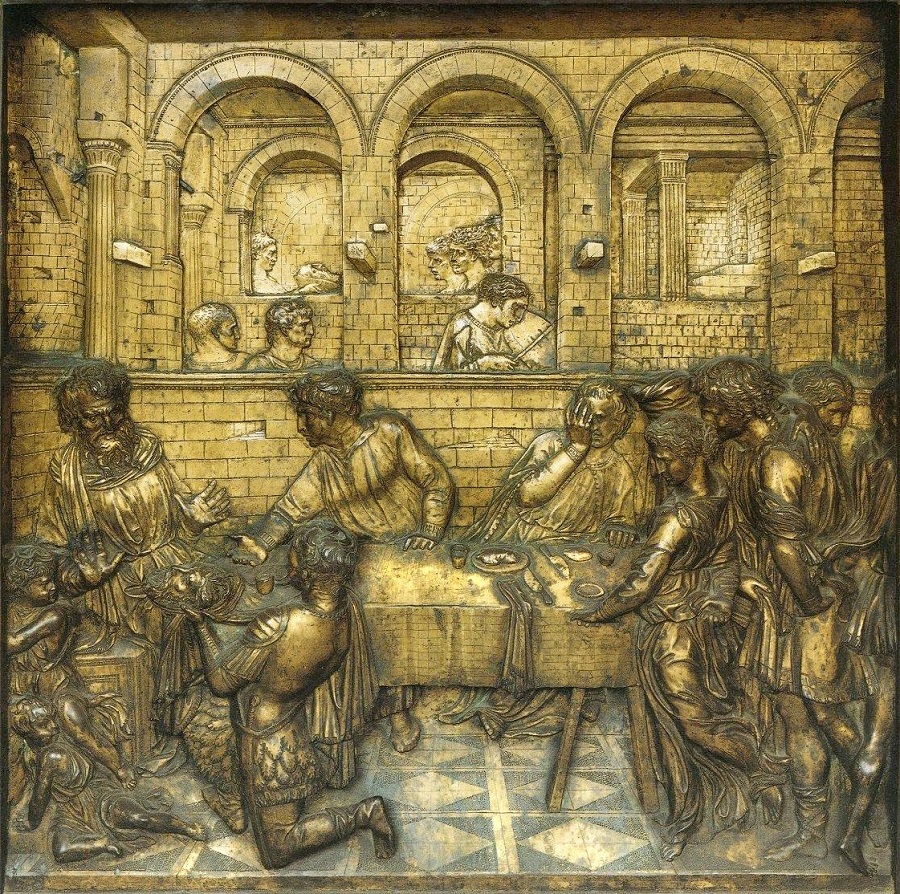

Also in this room is a small golden panel of brilliant virtuosity – a relief depicting “The Feast of Herod” (1423) from the Baptistery of Sienna. Donatello designed here, as never before, a scene with a Brunelleschian perspective in which the arrangement of the figures and the narration take place in four gradations of depth on a bronze plate. We can see, on approaching the work from the side, that it is no more than a couple of fingers thick but within those few centimetres, a whole story is taking place beneath the arches of a palace’s myriad rooms. In a foreground full of details, characters and gestures, Herod holds out his arms in rejection while a kneeling servant presents him with the head of John the Baptist on a platter. The rest of the characters allow the sculptor to portray an array of hairstyles, drapery, hand movements, musical instruments and terrified children fleeing the scene via its frame.

Donatello, The Feast of Herod (1423-1427), Baptistery of San Giovanni, Sienna

The Bargello Palace was built in 1255 as the seat of the Florence Consistory and was later used as a prison. The Greater Council Room is presided over by three Donatello works – “Saint George”, set in a high niche where he appears solemn and distant, his torso turned slightly and his frown focussed somewhere in the distance; “Marzocco”, the emblematic lion of the city and the bronze “David” that presides over this grand Gothic room.

Donatello Room, National Museum of Bargello, Florence

This “David” was a statue designed to be raised on a column and viewed from below. When Donatello thought of reviving this motif, the idea of a column, of bronze metal and of a nude figure became paramount. His choice was of a noble biblical character, prototype of Christ and emblematic shepherd of the Florentina libertas. Donatello deliberately distorted his sculpture’s body in order for it to be perfectly proportioned when seen at this level. The victor thus floated above Goliath's severed head while he gazed vainly at the crowd.

Donatello, David Victorious (1435-1440), National Museum of Bargello, Florence

“David” was a statue designed to be raised on a column and viewed from below. When Donatello thought of reviving this motif, the idea of this column, of bronze metal and of a nude figure became paramount. His choice was of a noble biblical character, prototype of Christ and emblematic shepherd of the Florentina libertas. Donatello deliberately distorted his sculpture’s body in order for it to be perfectly proportioned when seen from eye level. The victor thus floated above Goliath's severed head while he gazed vainly at the crowd.

“David”, cast for Cosimo de’ Medici, symbolizes among other things the relationship between the sculptor and the illustrious Florentine family. The ambition of Cosimo and Lorenzo de' Medici, fulfilled in 1434 with the return of the brothers from exile and materialized in the commissioning of a work that symbolized power. At first, this “David” presided over the main entrance of the “Casa Vechia” but was later transferred to the new palace on the Vía Larga. It was the first in-the-round nude figure sculpted in Italy since the Roman Empire. The adolescent, a disdainful ephebe whose fine face is framed by cascades of curls, wears a picturesque hat and a dismissive smile whilst his posture, in slight contrapposto, is an audacity of balance.

All decisions concerning “David” were always made with the agreement of Cosimo the Elder, Donatello's main supporter and patron. Vasari tells us that Donatello died "in his little house on the Via del Cocomero", near the site now occupied by the Galleria dell'Accademia. By then he had already completed what would be his very last work, the impressive pulpits of San Lorenzo, the church linked to the Medici. His workshop was located next to the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore. He had previously moved too many times to mention here but his final resting place has never changed. It is inside the crypt of San Lorenzo, just a few metres from the tomb of Cosimo the Elder.

Donatello, Pulpits of San Lorenzo (1460), Florence

Donatello, the Renaissance

Strozzi Palace and National Museum of Bargello

Via del Proconsolo 4, Florence

Curator: Francesco Caglioti

19 March - 31 July 2022

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Coliseum director Dr Rosella Rea accompanies ABC Cultural on an exceptional visit through some of the recently restored, but as yet unopen to the public, areas of this prodigious monument . Back in Madrid, we consult with Pritzker prize-winning Spanish architect Rafael Moneo. “You need to close your eyes to imagine this gallery ... Archaeologists have found coloured, stuccoed areas and many frescoes. We know now that the interior of the Coliseum was red. Only the exterior was light, the colour of limestone travertine. Ancient architecture was always painted in bright colours and to forget this is to veer from reality", says Dr Rea, as we walk through a gallery whose restoration began in 2012 - thanks to a €25 million funding grant from luxury brand Tod's – and, although now completed, is still absolutely out of bounds to the public.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

The Colosseum's Archaeological director Dr Rosella Rea accompanies ABC Cultural on an exceptional visit through some of the recently restored, but as yet unopen to the public, areas of this prodigious monument. Back in Madrid, we consult with the Spanish architect Rafael Moneo.

“You need to close your eyes to imagine this gallery ... Archaeologists have found coloured, stuccoed areas and many, many frescoes. We know now that the interior of the Colosseum was red. Only the exterior was light, the colour of limestone travertine. Ancient architecture was always painted in bright colours and to forget this is to ignore reality", says Dr Rea, as we walk through a gallery whose restoration began in 2012 - thanks to a €25 million funding grant from luxury brand Tod's – and, although now completed, is still absolutely out of bounds to the public. "We are in the highest reaches of the building, in an intermediate gallery that connects the third tier with the fourth and fifth. It was meant for the commoner. It is the only covered gallery preserved in its original state, with its frescoes, graffiti and ancient inscriptions."

Intermediate gallery connecting the third tier with the fourth and fifth. Colosseum (Rome). Photo: Marina Valcárcel

In this low-ceilinged, curved, narrow gallery the crowds would throng between lit torches or small windows of daylight, with shouting and screaming and the smell of food, dirt and latrines injecting the pure adrenaline of blood and death into the 100-day spectacle of festivals inaugurated by the Emperor Titus in 82 A.D. in his new Colosseum of Rome.

Robert Hughes insists we abandon the virtual images of TV series and video games portraying an "all-white Rome": white marble, white columns, men dressed in white togas looking very grave. "The real Rome was actually the Calcutta of the Mediterranean: crowded, chaotic and filthy," he writes in his book “Rome”.

View from the fourth tier. Photo: Marina Valcárcel

From this vantage point you have, by virtue of its height, the most impressive view of the Colosseum. We have a bird’s eye view of the huge skeleton of this stone beast with its open channels, its ribs of subterranean passageways, its arches jutting into the sky, the dark empty eyes of its vomitoriums, the rough skin of its concrete and its dark travertine covered in black scars, a wasp’s nest of square-shaped holes where metal clamps used to hold the stone blocks together before they were ultimately torn out and melted down.

From up here the Colosseum comes back to life in all its old colour, power and glory as it returns to the 1st century and 50,000 spectators enter the stands. Eighty arched entrances topped with 150 bronze statues and 40 golden shields at the attic level commemorate military conquests; senators and magistrates sit nearest to the arena, the commoner man on wooden benches in the top tier and the women and slaves in the "gods"; the roar of the amphitheatre becomes deafening, the grandstand is festooned again with marble and garlands of flowers. Above the windows of the highest level, the decorated beams hold the velarium that unfolds, manoeuvred by a special unit of sailors from the Miseno fleet to cover the amphitheatre with tarpaulin sails that protect spectators from the sun and shower them with water, steam, perfume and rose petals. The emperor, his family, the Vestal Virgins and the Roman priestesses sit on the podium while, through the Porta Triumphalis, the entourage of gladiators, musicians and hunters makes its entrance; opposite, through the Porta Libitinaria, their mutilated bodies will exit the arena ...

The words of the Dr Rea make perfect sense: "What impresses the visitor is not so much the visit itself as the fact of being here and living this experience."

View from the fifth tier and the buttress. Photo: Marina Valcárcel

So how are we to understand the secret to this feat of architectural engineering? The Flavio Amphitheatre, completed in the year 80 AD, reaches a total height of 52 metres; the major axis measures 188 metres and the smallest 156 metres. The total area covered by sand is 3,357 square meters. The Romans used slave labour, without which many of Antiquity's megalithic constructions, from the Egyptians to the Assyrian empire and Rome itself, would not have been viable. But how was it possible to build a monument capable of accommodating 73,000 people in eight years and without mechanical compactors, rotary mixers or any of today's motorized tools? Who invented the system of ramps and passageways that allowed the ingress and egress of the public in just 15 minutes? This system of mathematical accuracy is one that endures today in most of the football stadiums of the world and, of course, in all the bullrings that dot the geography of Spain in small amphitheatres. The Romans took so much from Greek art that they are sometimes considered mere continuators. As regards art, however, as important as the one who creates it is the one who passes it on. The Romans did indeed absorb Greek architecture and sculpture but they also endowed it with the gift of utility, multiplying it in terms of engineering and technical capabilities and, above all, political capacity. Roman art is understood better than ever from this high point of the Colosseum and it is an indescribable propaganda machine of imperial power. And the machinery’s cogs were activated by two generating factors - innovation in architectural materials and the very nature of the shows themselves.

Unrepeatable arquitecture

"The Colosseum, the Pantheon and even some Gothic cathedrals are examples of our architectural past that no modern architect would dare to build today. In the same way it would be difficult to reproduce the tempering of some Renaissance swords today, even though modern steel has great properties," Rafael Moneo points out in our conversation about the Colosseum back in his Madrid studio. "Roman architecture, and the Colosseum in particular, has that complete strength of definition that at times demands an architecture with a resounding constitution and huge dimensions. In this respect, the Colosseum, unlike the Pantheon, simultaneously resolves something very beautifully: the problem of form and use. It is an architecture that comes from Greek theatre; Greek theatres not Greek temples, because it’s understood that the problems of form are linked almost directly to the use that things are put to. In the case of the Colosseum it goes further still, with that slightly oval-shaped level, those specific measurements and that double focus of the ellipse set against the stricter, tougher condition of the circle", adds Moneo.

Interior view of the Colosseum, access gallery to the stands. Photo: Marina Valcárcel

Roman architecture was first and foremost practical. It fulfilled its propaganda function - to spread mini Romes throughout the empire - with military rigour. They would all have their forum, their basilica, their aqueduct, their amphitheatre... "The history of civilization is not understood without Rome, without the empire and without the Church. All of that has become architecture. Culture is deposited in architecture and that is the lesson of that city," concludes Moneo.

To this end, Rome relied on two revolutionary discoveries: concrete and the spread of brick. Greek architecture was based on the straight line: pillars and straight lintels. The genius of Roman architecture was that it built curved structures. This could not be done, at least not on any magnitude, in carved stone. A plastic, malleable substance was needed, and the Romans found it in concrete. With it they erected aqueducts, arches, domes and roads. It was the material of power and discipline. It was strong and inexpensive, allowing very large structures to be built. And size had a special appeal to the Romans when it came to building their empire. But also, with the production of bricks, the Romans came to generate a material at an almost pre-industrial level. Each colony of the empire had its brick factory, each with its own local peculiarity. "It was like amphorae in that each city had its own typology: those of Bética were big-bellied and narrow-mouthed, and so the oil that arrived from Andalusia was distinguishable from the rest that arrived at the port of Ostia from elsewhere in the empire", explains Dr. Rea.

No known author

It is not known who the architect of the Colosseum was. We can only imagine him through Alma Tadema's painting in which he is depicted as a mature, thoughtful man stroking his chin with his left hand while drawing a rough sketch of a very large building in the sand with his right. It is as if the Dutch painter had wanted to honour Architecture through the drawing that this imagined artist presented to Vespasian and which would seem to hold all later architecture within it: from St. Petersburg to the Capitol in Washington; from one magnificence to another.

"The overlapping of classical styles on the facade of the Colosseum became an inspiration for the constructive art of the Renaissance. All later palaces have their origins here," concludes Dr. Rea.

"The architect of the Coliseum", Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912)

Subterranean Hell

Barbara Nazzaro, the Colosseum's Technical Director, now joins Dr. Rea and both suggest we end this visit with a "descent into hell". The basements, about six meters down, are a humid-smelling web of blackened stone tunnels with water underfoot and here we recall the dark legend of the Emperor Nero whose spectre seems to inhabit these dungeons. Nero had the artificial pool of his Domus Aurea built here in the Colosseum's valley. His suicide in 68 AD and posthumous damnatio memoriae - a kind of historical anti-memory law - only served to bury the imperial residence but the emperor ended up giving his name to the beast. Colosseum does not mean 'gigantic building' but 'place of a statue', in this case of him, 35 metres high and cast in bronze that presided over the esplanade of that folly of extravagance that was Nero's residence.

Artist's impression of the bronze statue of Nero for the esplanade of the Domus Aurea

The basement was the secret machinery powering the spectacles taking place above in homage to the glory of the emperor: full-scale re-enactments and performances with lavish scenery, artificial forests and special effects. They housed everything from the dock where the ships anchored for mock seafights to the hunting extravaganzas. Exotic animals dazzled the crowds awed by the greatness of their empire: lions, panthers, leopards, tigers and elephants brought from Africa; wild boars, bears and deer from Germany. From the tunnels crammed with cages and by means of freight elevators, the beasts ascended to the arena in a matter of minutes. Down in this labyrinth, the stench of animals mixed with the smell of slaves and smoke from the torches. Metal supports and beams that reinforced the service lifts were operated by a system of winches operated by slaves. At first there were 28 elevators. "We are talking here about it taking more than 200 people to get them up and running," says Dr Rea. Later, 32 more lifts were built. Trapdoors would be raised for the animals to enter the arena. About one million wild animals were killed in the Colosseum during the time it served as a place of entertainment for the masses, according to Dion Casio. The different plants that grow today between the stones of the Colosseum ruins constitute a legacy from these animals. They were the ones who brought the seeds from distant lands, populating the Colosseum with plant species left in peace to bloom throughout the building.

Replica of one of the lifts from the basements of the Colosseum. Photo: Marina Valcárcel

Dock in the interior of the Colosseum. Photo: Marina Valcárcel

From the first centuries after Antiquity and during the Middle Ages, the amphitheatre belonged somewhat to whoever appropriated it: monks from nearby country and vineyard monasteries settled there, as did aristocratic families - like the Frangipani - who fortified it, ordinary people who made it their refuge, their business, their home in which they ate, slept and cooked. The Colosseum is unlike any other known building typology: it is not a temple, nor a palace, nor a church. As the centuries passed, this indeterminacy took on myriad contours: it would serve as a quarry for the construction of other churches - the travertine of its facade would become the stairs of St. Peter's in Vatican City, it would be filled with aedicules for the Via Crucis and it would be incorporated into the architectural projects of Bernini and Fontana who dreamed of building churches out of its sand and bringing its stories of martyrdom back to life.

“Quamdiu stat Colysaeus stat et Roma, quando cadet Colysaeum cadet et Roma, quando cadet et Roma cadet et mundus” ("As long as the Colossus stands, so shall Rome; when the Colossus falls, Rome shall fall; when Rome falls, so falls the world."). This epigram, attributed to the Venerable Bede (672-735), would now seem to have been a prophecy endowing the monument with a fundamental responsibility and centering it as a testimony to the survival of history, as the mirror of Rome and, in turn, the mirror of the world.

Entrance gate to the Colosseum. Photo: Marina Valcárcel

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- The Colosseum, the engine of Roman power - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

that God granted the world ten measures of beauty (yofi), nine for Jerusalem and just one for the rest of the world. The Holy City has no rivers, no sea view, no gardens. It is, rather, an ochre-hued stoney plateau set amongst valleys and dry riverbeds in the mountains of Judea. So what then is Jerusalem? Is it a concept, a wound, a state of mind? Jerusalem is two rocks and a wall. It's the custodian of the three symbolic stones of the three religions that derive from the same book: the Wailing Wall for Jews, the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock for Muslims. One could say that its power resides in its promise of the cosmic, or its being the epicentre of stories about creation. According to Enrich Klein's 2005 account, Jerusalem has been destroyed 12 times, sieged 23 times, captured 52 times and recaptured 44 times. It is the only city in the world where history is both the past and also the future. Whatever our particular faith or whether we even have one or not, here is where its chaotic, propulsive energy is to be found.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

It says in the Talmud that God granted the world ten measures of beauty (yofi), nine for Jerusalem and just one for the rest of the world. The Holy City has no rivers, no sea view, no gardens. It is, rather, an ochre-hued stoney plateau set amongst valleys and dry riverbeds in the mountains of Judea. So what then is Jerusalem? Is it a concept, a wound, a state of mind? Jerusalem is two rocks and a wall. It's the custodian of the three symbolic stones of the three religions that derive from the same book: the Wailing Wall for Jews, the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock for Muslims. One could say that its power resides in its promise of the cosmic, or its being the epicentre of stories about creation. According to Enrich Klein's 2005 account, Jerusalem has been destroyed 12 times, sieged 23 times, captured 52 times and recaptured 44 times. It is the only city in the world where history is both the past and also the future. Whatever our particular faith or whether we even have one or not, here is where its chaotic, propulsive energy is to be found.

Throughout history, a number of places have been venerated for their holiness: the Ganges and its passage through Benares in India, the Valley Of The Kings in Egypt or the tomb of the poet Hajez in Iran. They are all realities. Nobody is denying this. But Jerusalem poses myriad questions. Was it the Garden of Eden? Was it the cornerstone on which the Arc of the Covenant would be built? According to Hebrew legend, the temple was erected on the exact spot where the waters of the Great Flood sprang. The rock was called Ebhen Shetiyyah, the Foundation Stone, and the first solid body in Creation as God separated the Earth from the primitive bodies of water. It may have been here where King David watched Bethsheba as she bathed, which led to him marrying her. David's mortal works and personal failings left God with no choice but to instruct him to not build the temple himself but leave the task to Solomon, his son with Bethsheba. In the Book of Chronicles, David confesses: “God told me: You will not build a house in my name because you are a man of war." The Wailing Wall, where Jews still pray to this day, is believed to have formed part of the temple wall.

Jewish Cemetery, as seen from the Kidron Valley

Awaiting The Redemption

The future can be guessed at by looking down on the city from the top of Kidron Valley or Josafat where the 3,000 year-old and largest Jewish cemetery in the world stretches out below. There is precious little space left among the 150,000 tombstones for new burials. For this reason, the last remaining outer rows have long been bought up, at unimaginable prices, by grand Jewish banking families now living in Manhattan. They want to be assured of their future place for the day when, according to the prophets, God will initiate the Redemption there. All are buried with their feet towards Temple Mount, in identical 120cm plots. On Judgement Day, God must find them all facing the right way.

Kidron Valley spreads beneath the cemetery and seperates the city from the three hills to the west of Mount Scopus, seat of Hebrew University, the Mount of Olives and Mount Scandal. Inside its walls, commissioned by King Soloman the Magnificent of his arquitect Mimar Sinan, the same architect who festooned Istambul with its most beautiful mosques, the Old Town is divided into four sections: Armenian, Jewish, Christian and Muslim. Four separate worlds sharing the same sun and the same God. Each one of them smells different - cardamom coffee, hookah tobacco, sweet breads, dried lamb's blood. From the Damascus Gate, one can see women laying out spinach leaves on rags in the street; flags with the Star of David (Palestinian never, they're banned); young girls selling peaches and cherries from wooden carts; monks calling the faithful to prayer at the nearby Al-Aqsa mosque; young women wearing veils; nuns in blue and white habits, priests in black, Orthodox Jews in kaftans and black hats, Israeli soldiers with their UZI rifles cocked, stray dogs. And rubbish. A lot of rubbish. Shells exploding, ambulances wailing, remnants of barbed wire.

The rest of the Old Town encompasses a constellation of holy places. Stringent visiting restrictions at the two most significant non-Jewish monuments, namely the Dome of the Rock and the Holy Sepulchre, were introduced in 2017, perhaps in anticipation of the tension about to escalate around them.

Restoration work

At the time of writing (January 2018), King Abdullah of Jordan is on a visit to the Vatican. He calls the Pope “My dear friend and brother” and gifts him a painting representing Rome, the Eternal City. The Hashemite dynasty are custodians of Jerusalem's holy Muslim sites. Also happening around this time is the culmination of seven years' restoration work on the 1,525 square metres of mosaics at the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa mosque. Out on the esplanade, Jordanian and Palestinian restorers worked away in silence, at a time when rage was making its comeback. The restored mosaics, which decorate the walls and vault of this famous octagonal building, consist of over 2 million coloured glass tiles with gold, silver and mother-of-pearl. Contained within the gilt ones, in their crystal soul, is a fine layer of real gold.

The Dome of the Rock is the oldest Muslim building in the world. It guards the stone of Mohammed who, because of his affinity with the Jewish faith, also held Jerusalem as the Holy City. According to a tradition heavily steeped in poetry, Mohammed received here the first of his revelations from the Angel Gabriel, who told him he was to be Allah's messenger. Years later, Gabriel was to appear again, bringing the white horse, Buraq, which carried Mohammed at lightening speed to a sacred rock on the top of Mount Moriah. This was a key place in Hebraic faith for being the stone upon which Abraham offered his son Isaac to God as a sacrifice. From there, Mohammed ascended a staircase of bright light to the Seventh Heaven where he was proclaimed superior to the Old Testament prophets. This journey to heaven is remembered in Sura 17 of the Koran entitled: "The Children of Israel". When Caliph Omar arrived in Jerusalem in 638 AD CE, six years after Mohammed's death, he built a wooden mosque that would later become Al-Aqsa. Mohammed's heirs established their capital in Damascus and decided to make Jerusalem a place of pilgrimage as important as Mecca and Medina. They confided in Byzantine, Greek and Egyptian architects to build a stone cupola for over the sacred rock of Mount Moria; an octagon with with twelve interior columns and four piers supporting the golden hemisphere. These were the sacred shapes and numbers of Eastern religions. The smaller Al-Aqsa mosque, at the extreme southern end of the platform, was given a silver dome and gold and silver doors. These two sanctified structures were to become magnets for the faithful.

Interior of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Renovation of the Holy Sepulchre, which was completed in March 2018, freed the edicule from its corset of iron girders, a scaffolding that had constricted it since 1934. It can now be seen exactly as it was conceived in 1810. A team, led by the Athenian Antonia Moropolou, are unanimous in describing the most exciting moment of the nine months the restoration work lasted, as the removal of the marble cladding protecting the rock bench where Christian tradition believes the body of Jesus Christ lay. Through a tiny door in the Chapel of the Angel, antechamber to the tomb, a glass panel covers the marble slab, leaving the original rock of the tomb inside exposed.

The "Day of Rage”, December 2017. Streets of Ramallah.

The "Day of Rage"

The front pages of newspapers across the world went with various different analyses of the same photograph. A young man hurls a stone with his sling as a battle rages on around him. These were the streets of Ramallah on the "Day of Rage", so named by Hamas in order to fire up Palestinians against Trump's decision, the previous December 6th, to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and his decision to move the US embassy there from Tel Aviv. The young man in the photo has his face covered by the keffiyeh of a new intifada and his gesture is one of hate. He's the present-day Discobolus, a discus thrower of the Instagram era. The expansive curve of his stone throw is already turning into a spiral of violence. Neither side wants to lose their children again.

Seventy years ago, the United Nations agreed a plan to partition Palestine, which had been under British mandate since the end of the First World War. A little over half the territory was assigned to the Jewish state, as proclaimed officially in May of 1948, and the remainder was envisioned for a future Arab state. Jerusalem would be accorded corpus separatum status, a separate entity under international jurisdiction. But the war waged between the Jewish forces and Arab countries, until the armistice of July 1949 was signed, put paid to the UN's plans. The west of the city was occupied by Israel, establishing its capital there, and the east remained under Jordanian jurisdiction, as well as the West Bank. The Green Line of ceasefire dividing the city with barbed wire and barricades lasted until Israel's victory in the Six Day War of 1967. Since then, even her closest allies have maintained their embassies at a distance of 70 km.

Jerusalem is simultaneously glory and sin. Many are the writers who have left their mark on the palimpsest that is Jerusalem. From the 16th century travel guides, now decorating the display cases of the National Library in its Urbs Beata Hierusalem exhibition, to the words of Chateaubriand; "I stood, staring at Jerusalem, measuring the heights of its walls, memories from history all the while coming to me ..... Even if I lived to be a thousand years, never could I forget this desert that seems still to breathe the greatness of Jehovah and the terrors of death".

Measures of sorrow

However, claims The Economist, that aforementioned distribution of measures of beauty (yofi) from the Talmud might at times seem erroneous. And what if it were instead measures of sorrow that God gave the world? Nine for Jerusalem and one for the rest?

There are two instances of this in the city today. Yad Vashem is one of the most impressive museums in the world. Its objects, photographs and videos underline Man's capacity for creating destruction among his counterparts. One is Jerusalem's Holocaust Museum, 180 square metres of passageways and galleries charting the history of the extermination of six million Jews during WWII. Located on the Hill Of Remembrance, Yad Vashem was founded in 1953 by an act of the Israeli parliament. Moshe Safdie's building is astounding. A triangular prism seen to penetrate one side of the mountain and come out the other. The visual sensation is unique: a base in almost darkness but a sky lightly illuminated. Physical death but also spiritual life. "And to them will I give in my house and within my walls a memorial (Yad) and a name (Shem) that will never be cut off." Isaiah 56:5. Yad Vashem won the Prince of Asturias Award for Concord in 2007.

Yad Vashem Museum

A few metres away, and as if a continuation of the message, is Hadassah Hospital housing the world's largest skin bank. It has existed since the days of the years-long Second Intifada when the casualty figures screamed nearly a hundred suicide bombers, 5,000 dead and tens of thousands wounded, many of them burns victims. Here are kept, frozen in liquid nitrogen, 170 square metres of human skin, which is enough to treat about 100 people with 50% burns to their body. Jerusalem is all divisory lines, Vias Dolorosas, border posts and walls ~ much like Doris Salcedo's Shibboleth, a 546 foot-long crack in the cement floor of the Tate Modern, its 'scar' still visible today.

And its writers

Finally, Jerusalem today is also its writers. Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, books such as To The End Of The Land and real lived experiences, too. The eulogy that David Grossman read out at the funeral for his son Uri, 21, killed in combat by friendly fire in August 2006 when his jeep got hit by a Hezbollah missile, explains one way of living with a kind of severe serenity when surrounded by a sea of enemies. "For three days, every thought began with: "He/we won't". He won't come, we won't talk, we won't laugh ... Israel will have its own reckoning ... and we will act against the gravity of grief."

View from inside Yad Vashem Museum

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, Venice now finds itself at death's door, not drowning in the Adriatic's high tides but suffocated by mass tourism. UNESCO has extended until December 2018 its deadline for Venice to meet twelve criteria, to the letter, that might spare it being added to the World Heritage in Danger List alongside Aleppo, Damascus and the historic centre of Vienna. Around 9.30 in the morning, crossing the Campo Santa Maria Formosa towards San Zaccaria, there is still a real feel of authentic Vienna with children on their way to school, kiosks piled high with bundles of Corriere della Sera and Il Gazzettino and the local dialect of young Venetians stepping off gondolas and vaporettos en route to the Plaza's fresh vegetable stalls piled high with basil, chicory, vine tomatoes and aubergines.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Grand Canal, Venice

Classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, Venice now finds itself at death's door, not drowning in the Adriatic's high tides but suffocated by mass tourism. UNESCO has extended until December 2018 its deadline for Venice to meet twelve criteria, to the letter, that might spare it being added to the World Heritage in Danger List alongside Aleppo, Damascus and the historic centre of Vienna.

Around 9.30 in the morning, crossing the Campo Santa Maria Formosa towards San Zaccaria, there is still a real feel of authentic Vienna with children on their way to school, kiosks piled high with bundles of Corriere della Sera and Il Gazzettino and the local dialect of young Venetians stepping off gondolas and vaporettos en route to the Plaza's fresh vegetable stalls piled high with basil, chicory, vine tomatoes and aubergines. A short distance away, a woman in her 70s sticks up for one of the few bookshops still trading: "We are afraid our city will become the Las Vegas of the Adriatic" she says, pointing to a single book that seems to be crying out from the window display ~ If Venice Dies by Salvatore Settis. It's to the voice of this former professor and director of the Getty Centre of Arts in the 90's that Venetians cling. Settis implores and challenges us with the urgent question: "How much longer can La Serenissima survive tourism?"

Campo Santa Maria Formosa, Canaletto (1735)

Three ways to fall

Cities, according to Settis, die in one of three ways. By enemy destruction (see Carthage, razed to the ground by Rome in 146 BC); by an invader force ousting the indigenous people and their gods (see Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, annihilated by the Spanish in 1521); or because the inhabitants of that city gradually lose their memory and their dignity and abandon themselves to a slow amnesia (as happened in Athens). After the glory of the classical polis, that of Pericles, Phidias, Sophocles and Aeschylus, Athens first lost its political autonomy, then its cultural initiative and then, little by little, having sleepwalked through centuries in its marble whiteness, saw itself devoured by darkness until nothing at all remained of its identity. Only in 1827 did it awaken again by dint of a coup of independence.

The facts should mobilise us against such oblivion. Venice hosts 28 million tourists a year. That's four visitors per day per resident. The toll of this has been the systematic depopulation of the city. Only once before has Venice suffered a decline comparable to the current one and that was during the bubonic plague of 1630. The number of inhabitants has gone down from 174,808 in 1951 to 55,000 today. Compare that to the 66,000 tourists per day.

Venetians no longer want to live in Venice. Around 1,000 residents a year leave the city, a city with "the finest parlour in the world" according to Stendhal but which is becoming increasingly wilted and stagnant. Houses have become hotels. The proliferation of AirBnBs has meant a steep rise in rents. WiFi hotspots now outnumber the delicatessens that once sold prosciutto; the trattorias on the lively banks of the Zattere have closed down while young tourists in shorts and a rucksack crowd the bridges eating take-away spaghetti carbonara with chopsticks. Twenty years ago in the Rialto district, Venetians made their living selling each other fresh fish and artichokes. There was also a plethora of workshops making and selling Murano glass and masks to travellers who knew what they were buying and what it was worth. That Venice no longer exists. Nowadays, Chinese merchants sell Venetian masks made in China to Chinese tourists for one euro a pop.

Also now, while tourists queue for hours to go sightseeing at the Doge's Palace, the fascinating gallery exhibitions rekindling the glory of the city sit empty of visitors. John Ruskin's The Stones of Venice (Doge's Palace), Bellini/Mantenga (Querini Stampalia Foundation), Dancing With Myself (Punta della Dorada) and the 16th Architecture Biennial, to name but a few.

Monsters Of Steel

Venice, once the seat of great maritime and trading power, is in grave danger of being inundated by sea monsters weighing over 55,000 tonnes making their way up the Giudecca channel spewing out 1,500,000 passengers each and every year. The MSC Divina cruiser, for instance, is 67 metres high, twice that of the Doge's Palace. Every time one of these floating cities squeezes itself between the river banks, darkness obscures the alleyways and bridges of the Dorsoduro district, as if they were under a total eclipse of the sun. In June, some 25,000 residents took part in a local referendum, albeit without legal import, calling for a ban on these ships entering the waterways. Something quite unthinkable for the powerful lobby group of hotels, shops and rental agencies. In Venice, tourism essentially provides a living to 30,000 Venetians.

The debate has intensified since Prague, Amsterdam, Lisbon, Dubrovnik, Seville and Granada were likewise invaded by hordes of tourists. “Tourism-phobia is a cry of desperation by residents" insists the journalist Pedro Bravo in his 2018 book Excess Baggage. "We assume that the sum total of all tourist expenditure goes straight to the city in question but this is not the case. The tour operators keep between 40% and 50% of the money involved so the destinations hardly benefit at all but it is these latter who, nevertheless, are lumbered with the extra costs of policing, cleaning, hospitals and infrastructures". In the case of Venice, the situation is exacerbated by its island status and its size.

Dorsoduro, Venice

Head-to-head confrontation

The Venetian lagoon is the result of fifteen centuries of human intervention in the search for a balance between its needs and those of nature. It is forced to defend itself against the tides that flood through the three entry points and sink it lower time and time again. Venice has been at times Byzantine, Austrian and Napoleonic. The Doge's betrothals were played out from the sea in a procession of gondolas and sailboats to the Lido on the Feast of the Assumption. He brought the body of St Mark all the way from Alexandria, buried it under the Pala d'Oro of the Basilica and established the lion as state symbol.

View of St Mark's Basilica from the Doge's Palace, Venice

“The city that baffles the world" is an interdependent, organic set of buildings, communication systems and structures. A tapestry of logical threads connecting art, history and tradition and that is how we should view it.

In his famous Plan of Venice of 1500, Jacopo De' Barbari was already mapping the latticework of secrets under the current of canals and the division of the city into six sestieri neighbourhoods, representing the six teeth of the "ferro", the iron fixtures adorning the black prow of gondolas. But La Serenissima is not just synonymous with beauty. Behind the so-called "Glory of Venice", there was a power without which we Europeans would not be the same people we are today. Venice is the syncretism of East and West, it's Marco Polo, it's the island that ignored feudalism, it's commerce, music, the Arsenal heart of the naval industry, the boats and ships, the saviour of the classics since the time of Plato and Aristotle. It's Petrarch, the Marciana Library, the Aldo Manucio press. It's also the Battle of Lepanto, the architecture of the Palladium, the paintings of Carpaccio and of Bellini and Titian, the San Rocco monastery decorated with Tintoretto's most celebrated pictorial cycle of paintings.

And so, Venice appears to us as an insistent set of reflections. Marcel Brion wrote of it ~ "Beauty doesn't make its entrance until that moment when one has nothing left to fear in one's life".

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Rarely have spectacles been the protagonists of an execution. But those of Khaled al Assad had seen too much. Worn for over four decades by the Head of Antiquities for the ancient city of Palmyra, they had overseen the care and upkeep of every pillar of the great colonnade and every sphinx at the temple of Bel. In the spring of 2015, Al Assad was living a peaceful life in retirement but still fully committed to 'his' ruins. At the beginning of the Syrian conflict, Palmyra had seemed safe behind combat lines. However, in May of that year, ISIS militants were drawing closer. While the entire city emptied of its inhabitants and its resident Syrian army fled, the 82 year old Khaled al Assad came up with a plan.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

The execution of 25 Syrian soldiers by ISIS, Amphitheatre at Palmyra, July 2015

Palmyra after ISIS: The destruction of World Heritage sites and other forms of terror

Rarely have spectacles been the protagonists of an execution. But those of Khaled al Assad had seen too much. Worn for over four decades by the Head of Antiquities for the ancient city of Palmyra, they had overseen the care and upkeep of every pillar of the great colonnade and every sphinx at the temple of Bel.

In the spring of 2015, Al Assad was living a peaceful life in retirement but still fully committed to 'his' ruins. At the beginning of the Syrian conflict, Palmyra had seemed safe behind combat lines. However, in May of that year, ISIS militants were drawing closer. While the entire city emptied of its inhabitants and its resident Syrian army fled, the 82 year old Khaled al Assad came up with a plan. Mere hours before Jihadists entered the city, he summoned his son, Walid, and his son-in-law and together they selected 900 of Palmyra museum's most valuable pieces and organised their evacuation to Damascus by lorry. These are immediately followed behind by Walid and Assad's son-in-law, married to Assad's daughter whose birth coincided with the setting up of Palmyra's sentinel and who was named Xenobia after the Great Queen of the "pearl of the desert" herself.

The rest of the story is well-documented. Jihadists take the city, explosions are heard coming from beneath the temples of Bel and Baalshamim as well as the Arch of Triumph and the funeral buildings are riddled with mines. Images flood the newsreels and internet. Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO, calls the events a war crime. With the amphitheatre behind them, 25 beaten and bloodied Syrian soldiers are shot at point-blank range by the 25 sons of Jihad fanatics standing behind them, the oldest of whom appeared to be around 12 years of age. The backdrop is a huge black Caliphate flag. ISIS mobs waste no time getting into the museum where, to their astonishment, they find the walls bare and the showcases and pedestals empty. All that is left is an elderly man, in his office, waiting patiently for them. Al Assad is arrested and tortured daily for a month. On the 18th of August, his body appears in the city square, hung from a lampost by the wrists, a placard around his waist listing "the sins of he who directed the site of idols". At his feet is his severed head with the black-rimmed glasses put carefully back in place. The most macabre of images.

The Koran contains various verses dealing with decapitation: “When you encounter an infidel, direct your blows at his neck until death occurs." [47:4]. We are by now well familiar with the idea that for a Muslim this is the most humiliating way to die. Resurrection, or an afterlife, is not possible if the victim's head has been forcibly removed.

This brutal story is barely 2 years old yet only a week ago, the Director-General of the Ministry of Antiquities for Syria confirmed: “Since then, we have buried 15 civil servants here: four were decapitated by ISIS and the rest were killed by either snipers or explosions." Extremist executioners are creating a new category of Syrian cultural heritage hero.

Palmyra before May 2015

In a small Italian city

Recently, in the sleepy Italian city of Aquilea 90 km east of Venice, there was a notable little exhibition: Portraits of Palmyra in Aquilea that deserves mention. It was the first ever in Europe dedicated to the ancient Syrian site since its destruction. Some 30 sculptures, photographs and mosaics were on display with a view to underlining and spreading the importance of a cultural heritage that is in danger. And all of it, from the inscription at the entrance to the walls painted the same shade of blue as Palmyra museum's, is in homage to Professor Al Assad. Aquilea, known as "the mother of Venice", could be said to have hosted, in its own right, an exhibition showcasing the 'Venice of the Desert'. Two cities, both declared World Heritage sites by UNESCO, who interact with each other despite geographical distances via these masterpieces of art. Perhaps this should be the mirror through which other projects or start-ups or groundswells should see themselves in a Europe that, for some time, has been losing and then refinding itself incessantly. Art as a unifying influence. Or a sticking plaster.

Tomb bas-relief with portraits of Batmalkû and Hairan, Palmiya, 3rd Century AD

Irreplaceable Treasure

Resonating amongst the works on display at the exhibition could be heard two intersecting voices: that of Paul Veyne and the 127 pages of voyage into the past in his Palmyra: The Irreplaceable Treasure (Ed. Ariel, 2017) followed by the muted voice of Al Assad: “The oasis of Palmyra - he wrote - appears in the distance, protected on the west and north sides by a mountain range with Jebel Haian as its summit. In the east and south, the city opens out into infinity. A garden of half a million olive, palm and pomegranate trees surround the ruins like a crown of laurel leaves. Golden columns, tombs and, especially, the imposing mass of the sanctuary of Bel ..." This city, whose arquaeological richness is comparable only to that of Pompeii or Epheseus, was a settlement from 2000 BC onwards and a melting pot for many civilisations before being annexed to the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD. It later reached its maximum expansion during the reign of the great Queen Xenobia. Palmyra was the crossroads on the old Silk Route. In the second century AD, Aramaic and Greek were spoken by merchants, travelling or resident, as commerce thrived ~ the Romans bought incense, pepper, ivory pearls and silks from Persia, India and Arabia in exchange for wheat, wine and oil. And it was certainly the case when examining the faces engraved on the tombs of Palmyra's most powerful families that there existed a certain analogy with other parts of the Roman Empire, as well as shades of the Oriental. A modernity similar to the eclecticism we see today on any Manhatten or Barcelona street, the one Veyne called "faces of the citizens of the world".

Explosions in Palmyra, May 2015 - March 2016

Palmyra, that fertile queen of the desert, represents everything the fanatics hate: openness, cultural interchange, the notion of a patrimony for all humankind ... With its eternal beauty, it challenged the dark ages of brutality and ignorance. It was in the hands of ISIS between May 2015 and March 2016. The Spanish artist Goya had already painted the destruction of art in a series drawing from 1814. Captioned "He knows not what he does", it shows an absurd-looking, bare-chested man, arrogant, his eyes closed, brick hammer in hand. He has just smashed a statue to pieces. It could be a contemporary image. Although iconoclasm has always existed, from Byzantium to the Reformation, from the Russian Revolution to Nazi Entartete Kunst 'degenerate art', we are nevertheless now witnessing a new type of terrorism. Jihad by media. The Taliban produced images whose global impact had been exceeded only by footage of planes hitting the Twin Towers. Since then, there has been no let-up in the internet spread of Islamic propoganda which goes to show just how difficult it is to control what is posted and the impact of electronic images such as the destruction of ancient manuscripts in Mali, heritage sites in Jorsabad, the Great Mosque Of Damascus and the Krak des Chevaliers in Syria, not to mention the van attack on the Ramblas in Barcelona and the threats concerning the Sagrada Familia cathedral there. Some days ago, leaders from the UK, France and Italy spearheaded a proposal that internet giants remove extremist ISIS content in less than 2 hours. Urgent measures are required. As Veyne so rightly said: "To know only one culture, one's own, means condemning oneself to living just one life, isolated form the world that surrounds us."

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

The sublime is something that moves up profoundly, that lifts us. There is no sublimation without passion. This experience full of beauty, exalts the viewer to unusual levels of aesthetic or moral shock. The MUSA (Underwater Museum of Art) is submerged off the coast of Cancun, Mexico and is the largest museum under the sea, with over 500 sculptures done by Jason Taylor deCaires. It's one of those experiences that raises us by its greatness. Jason DeCaires Taylor (1974) is an English sculptor, with over 18 years of experience as a diver. He has received awards for his underwater photographs, which capture how his sculptures become something organic, living a continuous transformation by the effects of ocean.

Author: Elena Cué

Underwater sculptures.

The sublime is something that moves up profoundly, that lifts us. There is no sublimation without passion. This experience full of beauty, exalts the viewer to unusual levels of aesthetic or moral shock. The MUSA (Underwater Museum of Art) is submerged off the coast of Cancun, Mexico and is the largest museum under the sea, with over 500 sculptures done by Jason Taylor deCaires. It's one of those experiences that raises us by its greatness.

Jason DeCaires Taylor (1974) is an English sculptor, with over 18 years of experience as a diver. He has received awards for his underwater photographs, which capture how his sculptures become something organic, living a continuous transformation by the effects of ocean.

Photos: Jason deCaires Taylor

The microorganisms that inhabit the oceans, colonize the surfaces of these sculptures creating coral reefs. The sculptures are formed using a special cement mixture, sand and micro quartz concrete, producing a neutral Ph which helps these microorganisms colonize its surface, enriching his work and helping to sustain the environment. The creation of coral serves as breeding and nursery grounds for many species that form the ecosystem. In this case, aesthetics and utility come together in this sublime composition, as these sculptures are the ideal substrate for coral to grow on and eventually create a reef that sustains a richer marine biomass and foster the reproduction of the species.

Photos: Jason deCaires Taylor. Silent Evolution

Enmanuel Kant, in his essay "Observations of the feeling of the beautiful and the sublime", linked the feeling of the sublime with the idea of infinity, that which impresses us by the grandeur of the embodiments to which it leads (the mathematically sublime). To admire the composition of more than 500 life-size sculptures, each with its own personal face, as it was done thousands of years ago with The warriors of Xian, is a grand experience. The dynamically sublime would be all that shows its immeasurable power, as are the wonders of nature. The unlimited, mysterious, awesome, beautiful, majestic, magnificent and terrifying nature of the sea, enhances this effect on the disturbing sculptures. Therefore, the relationship developed between our understanding and our imagination, causes in us a sublime feeling towards what we observe.

Photos: Jason deCaires Taylor. Silent Evolution

What makes these artworks singular is the interaction between man and nature in a living creative process. For Aristotle, nature (natural) and art (artificial) had nothing in common, they are two different realities, since the laws that govern them are totally different. Therefore, is fascinating to be able to make these two realities merge into a whole. The man-made artificial work of art, undergoes a constant metamorphosis leading to something natural until the primal is hidden.

Photos: Jason deCaires Taylor

Jason DeCaires Taylor creates this synthesis between man and nature, art and science, where sculptures, with the sea as a metaphor for infinity are individualized as Apollonian forms immersed in the ebb and flow of the Dionysian.

Photos: Jason deCaires Taylor. Reclamation.

Photos: Jason deCaires Taylor

Jason deCaires Taylor's official page: www.underwatersculpture.com

- Jason deCaires Taylor and the sublime. Cancun. - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

I was greeted by warm sunshine when I visited the wonderful gardens of the Zabalaga house, home to the artistic legacy of one of the 20th century’s most important sculptors, Eduardo Chillida (1924-2002). The Museo Chillida-Leku (Gipuzkoa) project was initiated by the artist himself as a place to house a large part of his work. It consists of large and small scale sculptures, drawings, graphical work and his well-known Gravitaciones, also known as reliefs on paper. The archives are located in the old 16th century shed, lovingly restored by Eduardo and his wife Pilar Belzunce: by juxtaposing in this way, an interesting dialogue is created beween his older work and his contemporary work.

“I once dreamed of a utopia: to find myself in a place where my sculptures could rest and where people could stroll among them as if in a forest”.

Eduardo Chillida’s son, Luis, is today head of the Marketing and Communication department. Together we walked through the gardens and the parts of the grounds that were thick with trees, all full of the Basque artist’s sculptures. He told me about the huge effort required to keep the project going — a task which the entire family is devoted to, and which seems to be carried out professionally and responsibly. The grounds measure 13 hectares and are extremely well looked-after; it was lovely to be able to walk at leisure, admiring one beautiful sculpture after another.

Chillida’s unique artistic language, which he has written about in a number of texts, helps us better understand his thought process and his work. Space, time, limits, scale, emptiness, matter and horizon are all ideas which are heavily present in his visual language and which form the basis of his work. Light is another crucial element, one that is especially evident in the alabasters, as well as the idea of limitation. Chillida explores both space and emptiness: he sees both as necessary tools in the making of his sculptures.

Chillida’s philosophy is pure spatial metaphysics, which links him intellectually to Martin Heidegger. The philosopher’s thoughts in “Art and Space” (1968) are so closely aligned to Chillida’s idea of space that he actually asked the artist to illustrate his thoughts for him. According to the philosopher, sculptures create places — without them, places do not exist. I could really sense this philosophy coming alive while we were walking through the grounds.

“I believe that we all come from somewhere. Ideally, we should come from a certain place, we should have our roots somewhere, so that our arms may reach all parts of the world, and so that we may benefit from any culture, no matter where it may come from. Any place can be ideal for those who open their minds; here in my Basque Country I feel at home, like a tree with its roots in the earth beneath it, grounded in one place but with arms open to the world. I am trying to create the work of a man, my own work, and since I come from the Basque Country, my work will have a certain essence to it, a black light, which is uniquely ours.” Eduardo Chillida.

After the visit, I couldn’t help going to see the Ondarreta beach and the Peine del Viento sculpture. Chillida has created a whole new space in this beautiful beach, where one can lose oneself in contemplation of the sky, the sea and the earth among architecture that literally “combs the wind”.

My visit to the area was a great excuse to go on a gastronomic tour in San Sebastián, to please the palate rather than the eyes. This world-class tour is one of the best one can find in this region, where the Michelin stars per resident ratio is the highest in the world.

My food tour started at the Rekondo restaurant and dinner in Zuberoa (1 Michelin star). The following day, lunch at the Asador Etxebarri (1 Michelin star) and dinner at Arzak (3 Michelin stars). We finished off with a trip to Martin Berasategui (3 Michelin stars).

One of my favourite restaurants was the Asador Etxebarri, where Bittor Arginzoniz’s cooking is entirely charcoal-grilled (be it fish, seafood, vegetables or meat). The ingredients were all of the highest quality, full of a delightful charcoal and smoke taste and smell.

My other favourite was Martin Berasategui, where the menu is very light and creative, each dish an exceptional, innovative cooking experience.

In Rekondo I tasted typical home-made Basque food together with a first-rate selection of wines, which I am told is among the best in the world.

Yet another top restaurant is Zuberoa, located in a 15th century Basque country house. The head chef is Hilario Arbelaitz and it boasts a tasting menu that definitely deserves its 1 Michelin star.

To round things up, Arzak was a continuous flow of highly creative sculpture-like dishes. This is avant-garde cuisine which is constantly evolving, very different to what I experienced when I last came here many years ago.

"One must look for the untrodden paths." Eduardo Chillida. Something these chefs have certainly done...