- Details

- Written by Rafael Luque

Trying to review Romanian-born artist Anka Moldovan’s latest exhibition "that which bursts" is, I have to admit, an excersize in arrogance, akin to claiming one can describe the joy felt by a sparrow in flight or the beauty of Handel's "Son nata a lagrimar". It is unwise to even attempt to reduce down to a few words the complexity of her worlds which, while still our world, feature exotic singularities like the event horizon of a black hole.

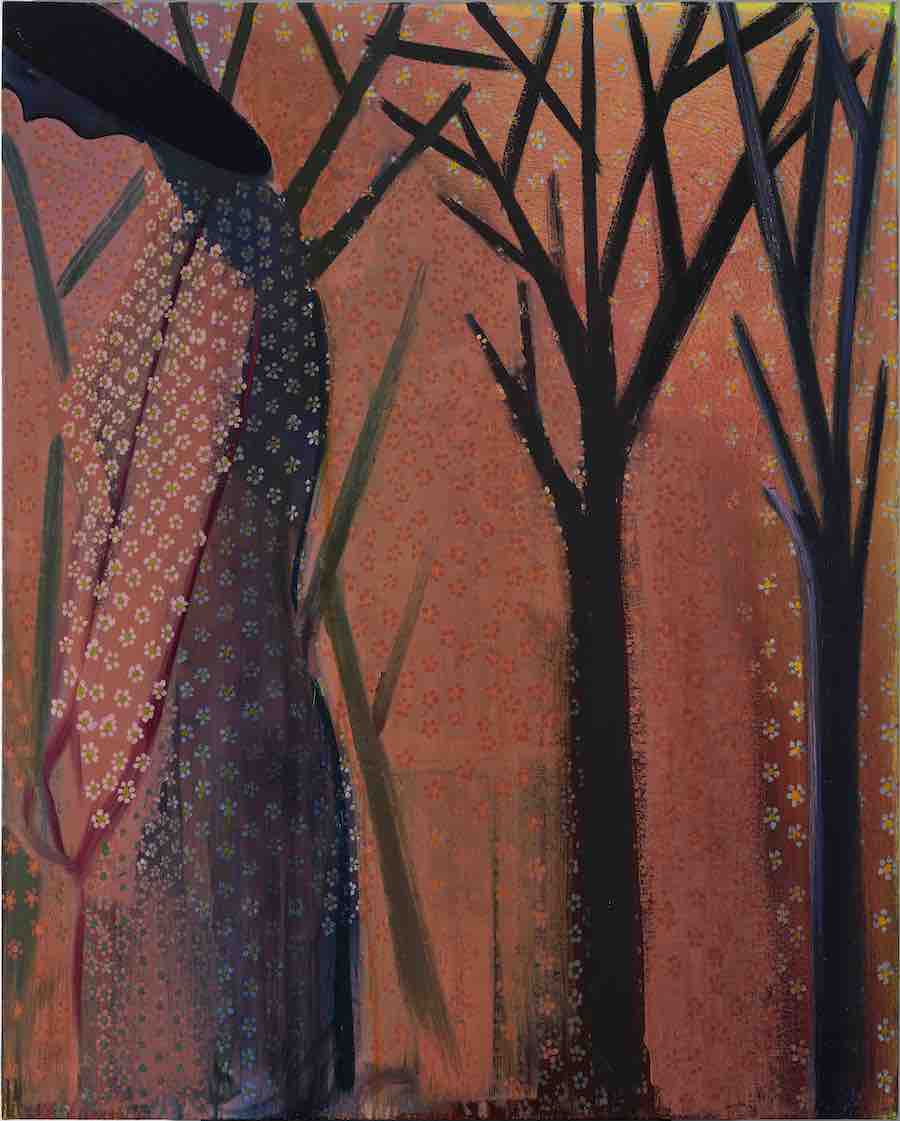

"Slit-man. Retina" (detail) (2023). Oil on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Trying to review Romanian-born artist Anka Moldovan’s latest exhibition "that which bursts" is, I have to admit, an exercise in arrogance, akin to claiming one can describe the joy felt by a sparrow in flight or the beauty of Handel's "Son nata a lagrimar". It is unwise to even attempt to reduce down to a few words the complexity of her worlds which, while still our world, feature exotic singularities like the event horizon of a black hole.

The beings and ambiences that emerge, pertinatious, from her paintings seem to live on that mysterious fine line between the visible and the invisible, between being and disappearing. Although it would be easy to divide the collection into four categories, there is still a common denominator that forms part of Anka Moldovan's identity as a creator: namely, her efforts to make the air perceptible, the constant human presence, somewhere between the corporeal and the abstract (despite which it is still possible to recognize oneself in some or other of her pedestrians walking with the determination of those who know and own their responsibility) and an undeniable capacity for synaesthesia.

Painting is, in principle, a visual art but, in this case, there are other senses involved. It is impossible not to feel the urge to touch, as if we were blind and reading Braille, the roughness of the reliefs that are an essential part of her work. Their meaning is as suggestive and mysterious as the "Voynich Manuscript" that, 600 years after its writing, remains indecipherable. Moldovan’s paintings smell of the rain and the sea because the beings in them seem always to be living in a thick fog that they wade through fearlessly in order to find us although, along the way, they run the risk of suffering a “Sudden Departure”, a euphemistic linguistic construct used to refer to the disappearance of 140 million people in the series "The Leftovers".

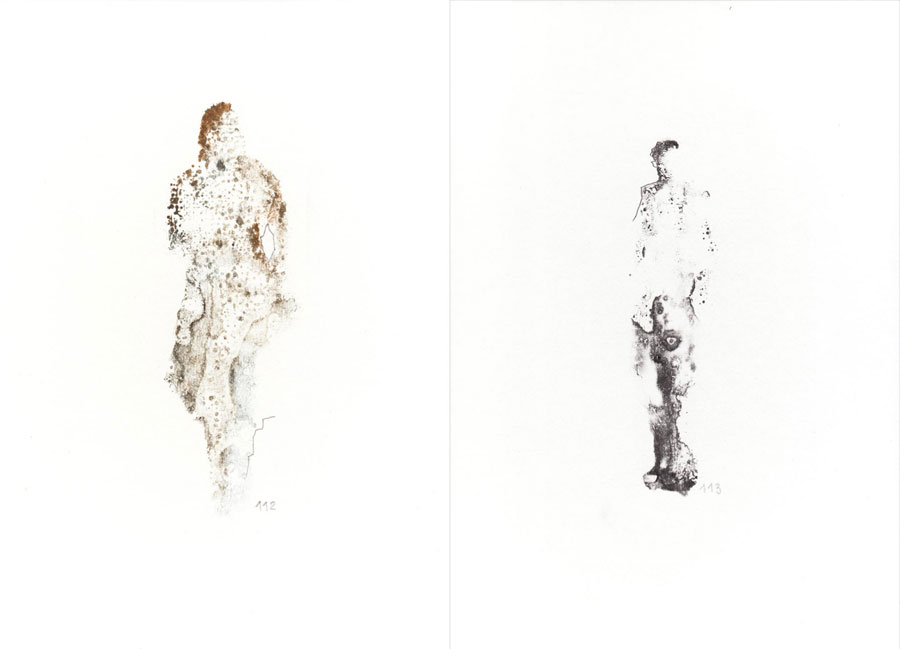

This happens in real terms in Moldovan’s work and comprises the "Reflections" collection - individuals who come to life in her paintings and, in the laborious construction of the fog, with its layer upon layer of oil painted and removed time and time again in search of a veladura glaze, it sometimes happens that one character is transformed, another vanishes into thin air, another fades away and, through a process of transference, is reborn on paper. The price of the pilgrims’ odyssey is to live alone, behind numbered windows and to be the only, or unique rather, creatures who are distanced from the firm, natural support of wood and exist on the human construct of paper. Odd observers these, echoes who from afar observe the paintings from which they come, each one a foreigner who discovers that the best way to accept what they have become is to remember what they once were, as Theodor Kallifatides wrote.

"Reflection 112" and "Reflection 113" (2023). Oil on paper. Courtesy of the artist

Moldovan's work can also be heard because it is narrative, it tells a story, incomplete, fragmented, like the name itself of this exhibition, "that which bursts", barely half a sentence, a subordinate clause lost in a world, our world, full of noise and fury, that shouts without listening and speaks without saying a thing. The art critic Carlos Delgado Mayordomo defines with poetic and meticulous precision: "Pain and love, despair and joy, absence and presence, are – without being exhaustive – some of the recurring themes in her paintings, where the desire to liberate and elevate what is properly human, to transcend it, is always visible."

What we see are troubled beings, carrying the burden of great responsibility, exhausted but not defeated, in pain, determined and ethical. Every paradise is a paradise lost and the visions that the creator portrays remind us that life rhymes with strife and not by chance but by causality. This is nowhere more evident than in the “Slit-men” suite - a transubstantiation of a poem by Nichita Stănescu that describes someone who “comes from beyond / and even beyond that beyond.”

Anka Moldovan, work in progress

The best way to describe them is the photograph above where Moldovan observes her "Slit-man. Presence" with the fascination and curiosity of an entomologist witnessing the arrival of the first insects on a corpse and, given the comforting gesture with which she touches her hair, it would seem that he is a stranger even to her. The four "Slit-men" are subtitled "Presence, Retina, Belly, Breath" and are entities somewhere on the spectrum between the savage and the human. They have arrived, although not through some fancy wormhole but by headbutting their way in. Seeing them gives new meaning to the scene in “Bladerunner” where the replicant Batty's face smashes through a tiled wall in pursuit of Deckard. In these four paintings, of the same height as the artist herself, there is hunger, pain and an intimidating power. They watch us and they see us.

If “Reflections” and “Slit-men” concern being rootless or uprooted, then the paintings from the “Earth” series are literally rooted, with actual roots.

"Earth" (2023). Oil on wood with root. Courtesy of the artist

They are women's heads with eye-catching buns and ornate up-dos, details that form part of the author's memory and memories. Another place, another time, other women and their ancestors, captured in a trivial detail that is testament to their greatness and generosity because their delicate and laborious braiding is seen by everyone else except they themselves. A root emerges from their hair because these women, in 1980s Romania, had their feet firmly on the ground and carried out their duty to care, feed, educate, provide love and security, sow responsibility and empathy and, ultimately, build true human beings.

Above left: "Birthing the world" (2021). Oil on wood. Above right: "Man, joy" (2023). Oil on panel (2023). Courtesy of the artist

With the root of a raspberry bush sprouting from her plaited hair, the natural and the artificial, nature and art share the same space. “It is not a simple stylistic artifice, but a bold reflection on the inevitably symbolic foundation of the visual arts: the roots, without the need to lose their own physiognomy, are read as a coherent part of human representation” according to Carlos Delgado Mayordomo.

And then finally, we come to the walkers, beings similar to us who move through spaces that we recognize (such as Madrid’s Gran Vía), prosaic passengers, citizens who inhabit the months as others inhabit cities and others metaphors. What makes them a society, while still remaining individuals, is that they are essentially beautiful and noble, physically and morally. Committed and empathetic, always moving forward without avoiding life's challenges. It is their greatness that makes me think that they only seem similar to us although, through the kind and loving eye of their creator, it is possible that we ourselves may become free from our sins.

Tireless and determined, they are surrounded by a mystical atmosphere that could be their soul, because they have one, or the air they exhale, because they breathe. One of these works, "Birthing the world" became the cover of the novel "A woman in the making" by Christian Bobin. This carefully crafted edition published by “La Cama Sol” makes for an illustrated book in a double sense, where the words of the gone-too-soon writer of silence and the paintings of the painter-of-air coexist.

"The flow of air". Oil on panel. Courtesy of the artist

"The mystery that bursts from her paintings - explains Carlos Delgado Mayordomo - is not just the expression of beauty but the celebration of life." Whether solid as concrete or ethereal as shadows, Anka Moldovan's beings whisper stories of resistance and hope. The latter is a necessity whereas the former is an act of love, the necessary defeat of oblivion and indifference - the stubborn will to keep asking questions, even if we sense we will never know the answers.

Translated from the Spanish "Los otros mundos de Anka Moldovan" by Shauna Devlin

- The Other Worldliness of Anka Moldovan - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

It must have been a dazzling sight to behold when the waters of the Nile flooded the lowlands of Ancient Egypt. The ground disappearing, the ditches filling in, villages emerging as if tiny islands and the swelling of the river setting the rhythm of time. There are some 1,000 kilometres between Aswan and the Mediterranean and covering three-quarters of this distance, Upper Egypt is a furrow hollowed into the desert.

Lintel of the temple of King Amenemhat III (detail), Egypt, 12th Dynasty, 1855-1908 BC, British Museum

It must have been a dazzling sight to behold when the waters of the Nile flooded the lowlands of Ancient Egypt. The ground disappearing, the ditches filling in, villages emerging as if tiny islands and the swelling of the river setting the rhythm of time. There are some 1,000 kilometres between Aswan and the Mediterranean and covering three-quarters of this distance, Upper Egypt is a furrow hollowed into the desert. The rest is made up of the delta, so called because the Greeks recognized in its triangular shape the fourth letter of their alphabet.

Around 5,200 years ago, some of the peoples living on the banks of the Nile among the papyrus plants and palm trees must have felt the need to reflect everything around them in writing and chiselled out the first ever hieroglyphs in history, in some or other pieces of stone. The oldest we know of date from 3,250 BC and together with cuneiform script are the earliest forms of human writing. How many thousands of years must human beings have been interacting without feeling the need to write anything down until then?

Lintel of the temple of King Amenemhat III, Egypt, 12th Dynasty, 1855-1908 BC, British Museum

London, in early 2023, finds itself embroiled in the furore surrounding the recent appointment of yet another Prime Minister and the upcoming coronation of Charles III at Westminster Abbey. However, one would be hard pressed to hear a pin drop in any of the galleries of the British Museum "Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt", a display featuring 240 objects from national and international collections in celebratation of the two hundred year anniversary of the decipherment of the Rosetta stone.

Exhibition room at the British Museum during "Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt"

The exhibition, dimly-lit and its black walls painted over with silver hieroglyphics, accentuates the sensation of being inside a pyramid. At its conclusion, in the final room, scenes of the banks of the Nile are projected in the round - its feluccas and palm trees, its temples and obelisks, its pyramids and birds in flight and behind them, the whole sea of the desert.

Fragment from the Book Of The Dead of Nedjmet, Egypt, 11th Dynasty, c. 1069 BC, British Museum, London

Sarcophagus of Hapmen, Cairo, XXVI Dynasty, c. 600 BC, British Museum, London

The display cases of the exhibition contain fascinating objects such as Champollion’s and Thomas Young’s own personal notes, four canopic vases preserving the organs of the deceased, the bandage of the Mummy of Aberuait and the 3,000-year-old Book of the Dead of Queen Nedjmet. Papyrus grew abundantly on the fertile, marshy banks of the Nile - a plant, whose name derives from the Greek word meaning "royal", raises its umbrella head on a stem that can reach up to six metres in height. Their stalks were used for shipbuilding, their fibres served to make ropes, mats, sails, baskets and sandals while its central pith created the papyrus on which to write.

Mummy of Bakentenhor, 12th Dynasty, 945-715 BC, Great North Museum

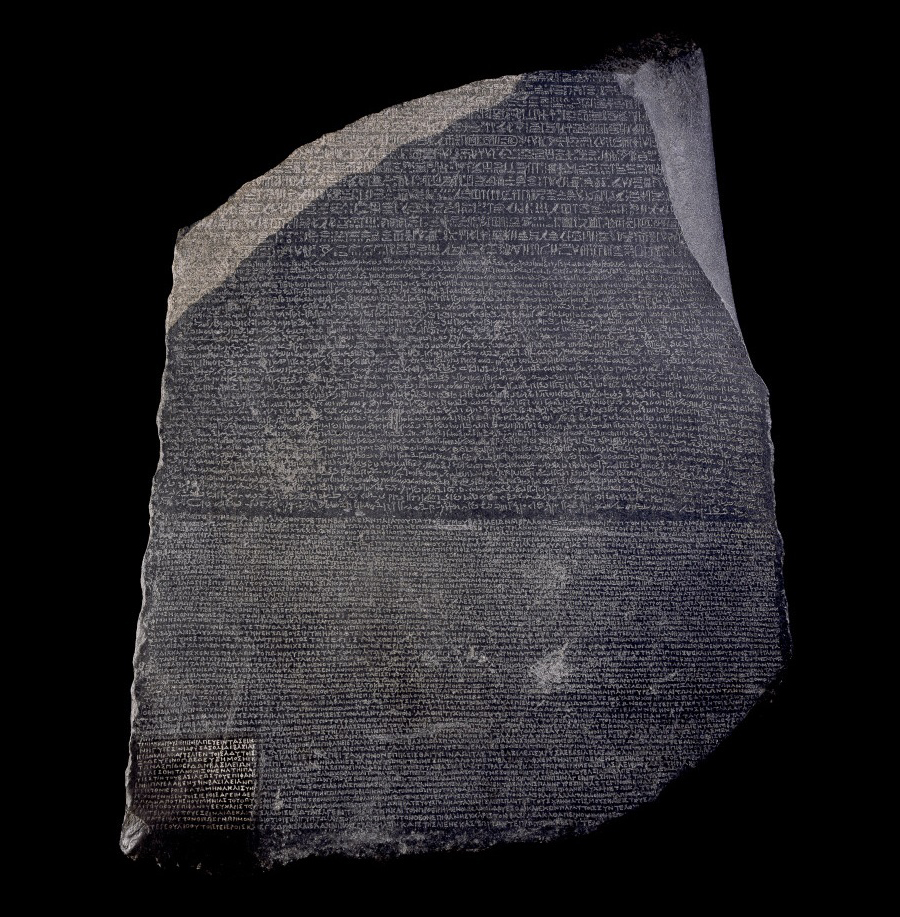

Nevertheless, the centrepiece of the exhibition is the Rosetta Stone, spot-lit as if by a magic beam, as if it were kryptonite. This fragment of an ancient stele is synonymous with the hieroglyphs that covered statues, monuments and papyri in Ancient Egypt. Its pictorial-style script was closely linked to Egyptian culture but although it was never used elsewhere, it was imitated throughout the kingdoms of ancient Sudan and appears to have inspired the Proto-Sinaitic script, in turn a possible distant ancestor of the modern alphabet.

Rosetta Stone, 196 BC, Ptolemaic Dynasty, British Museum, London

The first pages of Jean-François Champollion’s book, “Egyptian Pantheon”, open with a description of Amun - a god in human form usually seated on a throne. His skin is blue and his beard is styled as the black appendage characteristic of male divinities. When this same appendage appears on coffins, it indicates the mummy of a male. Held in his left hand is a sceptre crowned with a bird's head and it is the sceptre common to all the male divinities of the Egyptian pantheon. In his right hand, he carries a cross, surmounted by an oval or handle-shaped loop - the symbol of divine life. He wears a tall double-plumed royal headdress. A long blue ribbon cascades down his back. It is an aesthetic so powerful it begs the question - if the 19th century was one of revivals, namely, the use of visual styles that consciously echo an earlier architectural era (this being the case of Pompeii and Pompeian styles, Gothic and Gothic Revival and Neoclassicism), what then is the reason why a taste as refined as that of Pharaonic Egypt was not also taken as inspiration for the decoration of future palaces, clothing, furniture or tableware?

Statue of an anonymous scribe, Egypt, 5th Dynasty, 2494-2345 BC, Louvre Museum

The story of the Rosetta Stone has an inexplicable force. In December 1797, Tipu Sultan of Mysore in India asked Napoleon for help in quelling the growing threat of British power in India. It was then that, in the margins of a book about the Great Turkish War, Napoleon wrote: "Through Egypt, we will invade India." Emboldened by victories in Italy but frustrated by his attempts to invade England, Napoleon landed in Alexandria on July 1, 1798 with an army of 40,000 men. He was accompanied by the Commission des Sciences et des Arts (Commission of the Sciences and Arts) that brought together the most brilliant French minds and that, in the spirit of the prevailing Enlightenment, was to investigate and map both ancient and modern Egypt.

In mid-July of 1799 and faced with an imminent attack by Ottoman naval forces wishing to avenge Napoleon's campaign in Syria, the French reinforced their coastal defences. In Rashid (Rosetta), a port city on the western bank of the Nile delta, the demolition of Fort St. Julien was ordered and a block of granodiorite stone appeared among the foundations, a fragment from an ancient Egyptian stele with a decree published in Memphis in the year 196 BC under the name of Pharaoh Ptolemy V. The decree appeared in three different scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphs at the top, Greek at the bottom and between the two an unknown inscription initially believed to be Syriac.

Its pivotal role in the decipherment of hieroglyphs was immediately recognized. It was dug out of the dust, cleaned, and the Greek section was translated. Afterwards, it was transported by boat up the Nile to the Cairo Institute where its discovery was announced on August 19, 1799. There, the first and most crucial task was to make exact duplicate copies of the texts. Two young Orientalists recognized the central inscription as Demotic, a cursive script of the Egyptian language that they had seen before on papyri and mummy bandages.

Copying by hand would have meant, in addition to the risk of human error, months of work. It was decided to clean the stone and to leave the water in the crevices, its surface was covered with ink and traced onto sheets of damp paper. Thus, on January 24, 1800, a reverse copy was created in black on white that could be read with a mirror or via a light source. In Paris 22, years later, Jean-François Champollion presented his discoveries on hieroglyphs to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Two weeks earlier and after exhausting and exhaustive research that had seriously affected his health, Champollion had succeeded in deciphering the names of Cleopatra, Ramses and Thutmose III and, therefore, the writing of the ancient Egyptians.

Medal commemorating Thomas Young, mid 20th century, British Museum, London

Over time, the understanding of hieroglyphs was lost as the culture of Ancient Egypt was swept away by waves of conquests and occupations. The Arab invasion of the 7th century brought Islam and with it both the Arabic language and a succession of rulers culminating in the rule of the Mamluks.

Today, the Rosetta Stone is the British Museum’s most visited piece, with the bicentenaries of its decipherment along with that of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb again stirring up one of the most contentious debates of recent times, namely, renewed calls for the restitution of artefacts and antiquities to their countries of origin. The disputes have resulted in some agreements being reached but each case is different and, for Western museums, some emblematic pieces are considered untouchable and will always be the Cultural Heritage of all humankind.

The reflections of Egyptologist Silvio Curto illustrate why that is: "What was established during the Pharaonic era was the concept of the supreme dignity of the human being and that must be returned to and perfected throughout history, from Socrates to Kant."

Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt

British Museum, London

Curator: Ilona Regulski

13 October 2022 - 19 February 2023

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Hieroglyphs : Shining A Light On Ancient Egypt - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

It has been 62 years since a young artist, recently arrived in Paris having fled from communist Bulgaria stowed away in a train carriage, began painting sketches with the dream in mind of one day wrapping the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. That young visionary along with Jeanne-Claude Guillebon, his wife and other half in life and in art, are no longer with us, she having died in 2009

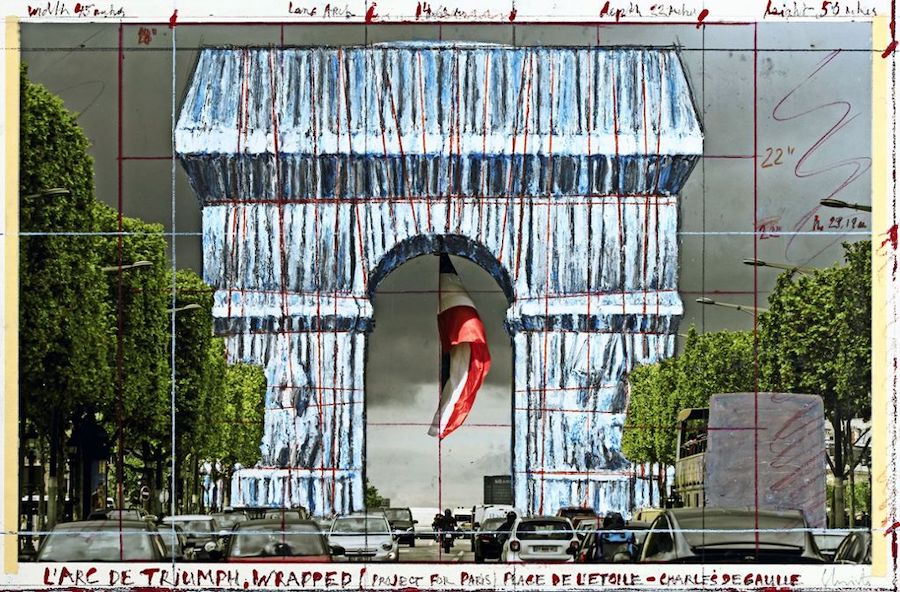

Preparatory drawing for the Arc de Triomphe installation in Paris (2019)

It has been 62 years since a young artist, recently arrived in Paris having fled from communist Bulgaria stowed away in a train carriage, began painting sketches with the dream in mind of one day wrapping the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. That young visionary along with Jeanne-Claude Guillebon, his wife and other half in life and in art, are no longer with us, she having died in 2009 and he on 31st May 2020 in New York, shortly before his 85th birthday. But this coming 18th September, and over 16 days, the Arc de Triomphe will, at last, be veiled in 25,000 square metres of silver blue fabric fastened with three kilometres of red ribbon rope. Everything had been measured out, drawn up and written down by its creators.

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff was born on 13th June 1935 in Gabrovo, Bulgaria and that same day in Casablanca, Morocco, Jeanne-Claude Guillebon was born. Above all else, Christo and Jeanne-Claude symbolise a love story that lasted the entirety of their lives. Between 1953 and 1956, he studied ‘Socialist Realism’, as mandated by the state, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sofia. He was so precociously and highly gifted a draughtsman that his mother insisted he have drawing lessons from the age of six. He fled communist Bulgaria in 1957 for Paris, a city that he had chosen as his destiny from the outset. There, he made ends meet for the first few years by painting portraits of the upper classes. In March 1958, a few months after his arrival, he met Jeanne-Claude who came from a military family with little connection to the world of contemporary art but who adapted to his life with enthusiasm, intelligence and passion. From 1961, they began working together and, this same year, on the occasion of their first solo exhibition in Cologne (Germany), they mounted their first temporary installation at the city’s port. Christo, at that time in the grips of an obsession, was wrapping everything up, even his wife's high heels. Those pieces would become the catalyst for the spectacular environmental interventions we know today. As of 1964, they settled in New York.

Christo and Jeanne Claude in their New York studio with sketches of Surrounded Islands in the background (1981)

Jeanne-Claude's contribution has often been described as the mere administration of contracts and sales yet it was much more than just that. Such was the passion both she and her husband felt for their joint work, they would travel on different planes so that, in the event of one’s crash, the other could continue to fulfil their destiny.

They dedicated more than 50 years to encasing landmarks and landscapes in cloth - ephemeral works that captured the imagination of the whole world. However, Christo has said that they never thought about the impact their work would have on generations of artists to come - a humble claim for a legacy like theirs, among the first artists ever to leave traditional gallery space and take their work as far away as the Australian coast and the German parliament. They wrapped valleys in curtains, covered islands in drapes and braided fabrics between bridges. Nothing seemed unconquerable.

Surrounded Islands, Bay of Biscayne, Florida (1980-1983)

The profound and loaded significance of the word "freedom" was undoubtedly the beacon guiding all their projects and the key to their work as well as their lives. "I was really drowning in that horrible Soviet regime. I couldn't give up an inch of my freedom," Christo said. "All these projects are completely irrational, completely useless. No one needs them. They can’t be bought. They exist in their time, impossible to be repeated. That is their power."

In order to explain their work, former refugee Christo has said that he considered all of their creations to have been marked by nomadism. "The fabric is the main element to transmit this. The projects have many complex parts but the fabric is a quick thing to assemble, like the Bedouin tents in nomadic tribes."

The Gates, Central Park, New York (February 2005)

From their home in New York shortly before his death, Christo stressed that their works, despite being temporary, are not performances - they are sculptures that cannot be owned. In that sense, he mocked the art market and its most recent, grandiose productions. Granted, all of the preparatory drawings and materials have been put up for sale over the years but self-financing was always their sole modus operandi. Despite each work requiring huge sums of money and employing hundreds of people, this allowed them to fly free and far from the bonds of any concessions, impositions or patrons.

Running Fence, Sonoma, California (September 1976)

The only dues Christo and Jeanne-Claude incurred were in the form of the permits they had to obtain - bureaucratic battles lasting years and taking its toll on many of their illusions, but Christo thought this journey helped gestate their pieces: "The work of art reveals itself little by little throughout the process of getting permits." Many attempts failed. Despite Jeanne-Claude's gift for negotiation, 23 projects saw completion over the years but 47 did not.

Among the projects they did succeed in realising was 1983's "Surrounded Islands", eleven of them ringed by rivers of pink cloth in Miami’s Biscayne Bay. Also in 1985, they completed their first major project in Paris - covering the capital’s oldest bridge, the Pont Neuf, in fabric after many months of dispute with the mayor at the time, Jacques Chirac, as detailed in the fascinating documentary "Christo in Paris".

Pont Neuf, Paris (1985)

Between 24th June and 7th July 1995, their then most ambitious work, “Germany”, was installed in Berlin. In the space of two weeks, five million people from around the world came to see the Reichstag wrapped. This installation transformed the seat of German politics after its reconstruction by Norman Foster who added the famous glass dome. Christo and Jeanne Claude had fought for 23 years to get the permits and on 23rd June, the plastic panels shielding it were removed - some 100,000 metres of fabric tied round with ropes one kilometre long to make the outline of the building visible. Christo said that, until 1989, the Reichstag had been a mausoleum, a sleeping beauty that they had reawakened. The building fascinated him as a symbol of freedom and its wrapping proved to be an astonishing feat of technology. David Bourdon, Christo's biographer, defined the Bulgarian artist's philosophy of art as "revealing something by hiding it."

Wrapped Reichstag, Germany (July1985)

After the Reichstag would come "The Gates" (2005), a 23-mile route through New York's Central Park dotted with 7,503 doorways hung with saffron-coloured panels blowing in the wind. And, more recently, "Floating Piers" (2016), comprising three kilometres of floating pontoons on Lake Iseo (Bergamo, Italy).

Arc de Triomphe, Place de l’Étoile, Paris (1963)

At the time of his death, Christo had another project in the pipeline – the wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, an intervention that had to be postponed until September 2021 due to the outbreak of Covid 19. Concurrently, the Pompidou Centre held an exhibition dedicated to the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude and focusing on their French projects.

The plans for the Arc de Triomphe were approved in just one year: "Thank you to the young President," said Christo, referring to Macron, but when asked if this was a sign of greater understanding and acceptance of his work in France, he replied with a loud and unequivocal "No!" and went on to explain that "For each project, we have a thousand people trying to help us and another thousand trying to stop us". Running in tandem was an exhibition at Madrid’s Guillermo de Osma Gallery paying tribute to this marriage of artists and featuring fifteen drawings associated with Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installation projects.

Preparations for L'Arc de Triomphe Wrapped, Paris (20 July 2021)

The Arc de Triomphe, with its huge historical significance, was built between 1806 and 1836 to celebrate France’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz under Napoleon’s command and fulfilling this promise to his men - "You will return home through arches of triumph". Measuring 49 m high and 45 m wide, it was designed by Jean Chalgrin along with Jean-Arnaud Raymond and inspired by the Arch of Titus in Rome. It sits on a hill crowned by the Place de l'Étoile from which radiate twelve avenues designed in the 19th century by Baron Haussmann. The historic war portal, with its iconic bas-reliefs and famous "The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792" sculpted by François Rude, will see its old silhouette spruced up for 16 days. Twice as many metres of fabric as its surface area will be used: "What we propose is a new structural dimension thanks to this beautiful fabric," Christo said. A project of this magnitude will require the labour of around a thousand people and "It will not be something static; it will be like a living being which will move with the wind; it will not be something made of bronze, nor bricks. It will be something that transmits the play of wind and sunlight," he said, inviting us to dream his dream.

Because what is compelling about these artists was their ability to force the spectator to become newly aware of an environment they had grown so accustomed to looking at, it had become invisible. It is by concealing it that it takes on the prominence it deserves. And so, now, Napoleon's Arc de Triomphe will once again be the arch celebrating another conquest - that of Christo and Jeanne Claude's work of wrapped art with its scaffolding nailed, this time, to the sky.

Christo & Jeanne Claude 1960-1970

Galería Guillermo de Osma

Claudio Coello, 4

Madrid

9 September - 15 October 2021

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- Christo & Jeanne-Claude: Wrapping The Arc de Triomphe - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

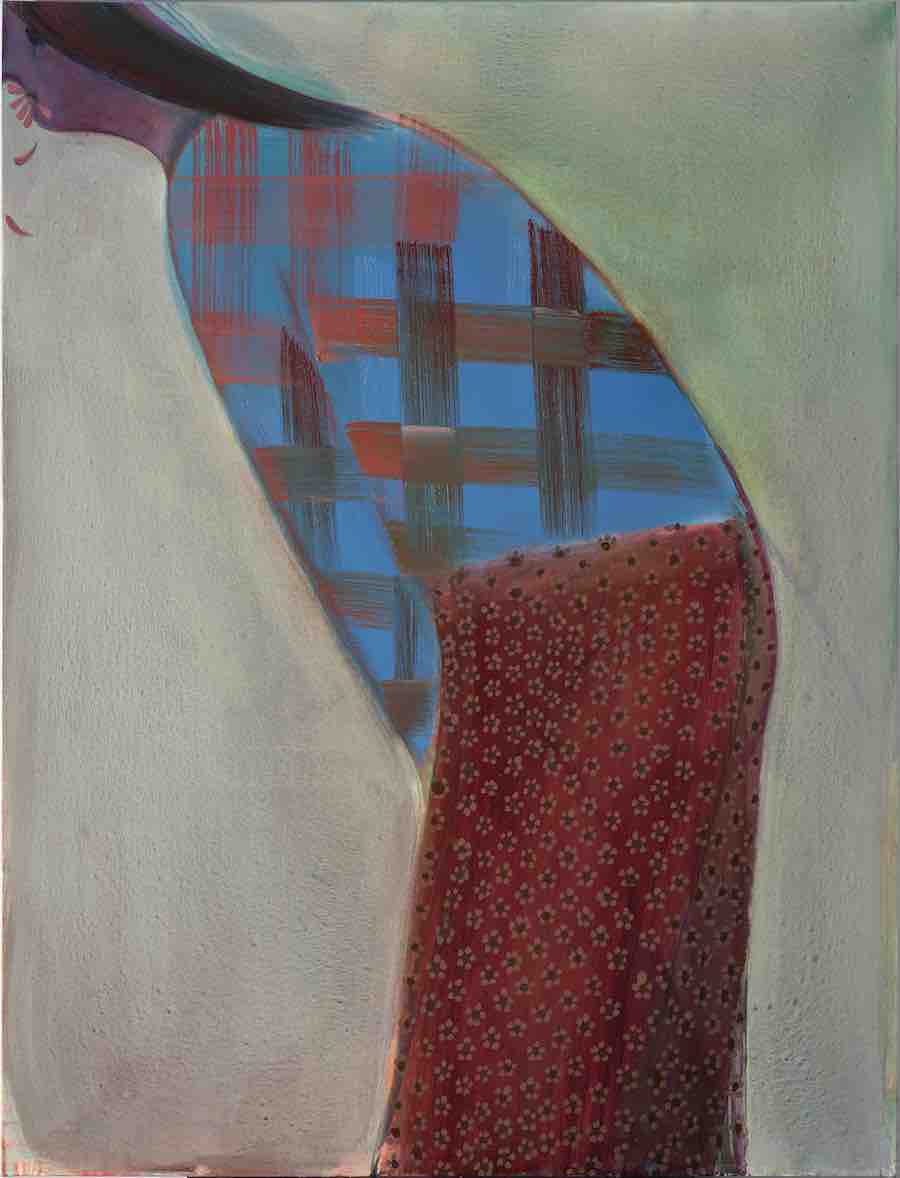

The Fahrenheit Gallery, Valeria Aresti's beautiful Madrid art space, is currently hosting the exhibition “Some Other Sunset” by rising New York star, the painter Heidi Hahn (b. Los Angeles, 1982). It comprises a series of 7 medium-sized oil paintings and 8 drawings, each of them dominated by the silhouette of a female body. These are women lost in thought, silent and, for the most part, in a forest lit only by the sunset.

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 4, 2021 oil on canvas

The Fahrenheit Gallery, Valeria Aresti's beautiful Madrid art space, is currently hosting the exhibition “Some Other Sunset” by rising New York star, the painter Heidi Hahn (b. Los Angeles, 1982). It comprises a series of 7 medium-sized oil paintings and 8 drawings, each of them dominated by the silhouette of a female body. These are women lost in thought, silent and, for the most part, in a forest lit only by the sunset. Their faces are schematic, some have neither mouth nor eyes, but even so, they seem given over to deep, prolonged thoughts and lost in a loneliness that is palpable in each of the brushstrokes that compose the sleeve of her sweater or the rays of golden sunset on her shoulder. Through them, Heidi Hahn seems to want to sign a declaration of principles that distance her subjects from the classical canon and its interpretation, widely-held until the beginning of the 20th century, namely, the naked bodies of women as the focal point of their beauty. Instead, she wraps them - or rather shields them, like a cuirass - in clothing that is loose-fitting, neutral, warm and nondescript. Their faces, barely hinted at, also alert the visitor to the fact that, in this exhibition, physiognomy takes a backseat to the volume of the body. There is also a lot of silence, stillness and an incessant question floated on the air: What are these women thinking about?

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 5, 2021 oil on canvas

From the outset, the contour lines of these bodies seem vaguely but surely reminiscent of Matisse and also, due to their solidity, of Picasso from his classical period. Matisse and Picasso, two undisputed trailblazers who, by the same token, arguably set both the standards and the constraints preventing young artists from being free to step outside the confines of some very marked, very recognizable patterns. Playing supporting roles in this exhibition are the simplified outlines of trees, hazy, barely there, and, in most of the works, the coral pink lighting of a sunset. It is, perhaps, this twilight colour that lends a somewhat sad, prolonged tone and very intimate voice to these women suspended in time. On these bright spring days in Madrid, the autumn light in Hahn’s paintings, the red sunsets, the leafless trees with black trunks, seem somewhat far removed from us. And yet, there is something deeply familiar to us in the message communicated from those lonely, pensive figures. And so it is that these women, lacking in form and expression, beguile us precisely because they confront us with something that is strangely close, something that is palpable in every square metre of Madrid’s pavements: loneliness, introspection, doubt. Hahn's women return us to the most fundamental questions, the ones that fill our lives and cities today during what will hopefully be the last days of the pandemic. Who are we, where are we going, what is going to happen now?

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 2, 2021 oil on canvas. Never Mind a Sunset 4, 2021 oil on canvas

Hahn's peculiar way of dressing her subjects is very much in keeping with her idea of altering the function of clothing so as to turn it into something that shifts between a layer of protection and an architectural covering: "I have painted women for a long time now just because I feel like I don't know if I represented them yet in a way I find truly convincing [...] I keep chasing this idea of like 'oh I like the iconic idea of women, but I don't like the classical.' I don't like romanticism that's through the lense of the male gaze; the cliché male gaze. I care about how I see these women and how I want to represent the women in my life [...] These women are trying to become something that they don't necessarily have access to yet. And, so maybe the paint tries to point them in the right direction, if that makes sense, it's trying to give them that strength where there is still that vulnerability, there is still something that is not quite figured out and that's why the figures are looser, and their faces have this idea of falling apart while trying to become something that is very solid." says Hahn. The attention to detail that Hahn pays to the fundamentals of technique is powerful - line, light and colour are the three keystones of an archway – her archway - leading us through areas of flat colour and transforming them into places of feeling and emotion. Brushstrokes ranging from the almost liquid and transparent to the thickest, loaded with pictorial mass. Here, in a large number of canvases, she uses a striking technique, namely - painting simple flowers in repeated patterns as if they were on printed fabric or wallpaper. Up close, the texture of these fake block prints makes them almost touchable which leads us to believe that Hahn transforms feelings into something palpable.

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 6, 2021 oil on canvas

These paintings are a tribute to ‘woman’ and her inner life. The way the paint is applied in different layers intensifies the narrative of each painting, calling to mind Edvard Munch and his search for the psychological portrait. Hahn strives to capture emotions and pent-up feelings. She turns the average woman, the one going about her daily routines, into her icon. Her anonymous characters seem lost in their own worlds and thoughts as they shop, sweep, prepare food, or tap on their mobile phones. They are, therefore, in total contrast with the widely-held consensus on ‘woman’ today – that she is more preoccupied with her appearance, fashion fads, the gym and the rat race. Hahn, however, avoids all emphasis on the physical aspects of her models, or even their femaleness, to accentuate instead their moods. This is why Hahn speaks of a "narrative formalism", referring to the amalgamation of paint and figures that happens in her work.

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 1, 2021 oil on canvas

Hahn likes to work in series of sometimes up to 14 canvases at a time. She groups them together in her studio and works on them, moving them around, looking for connections between each of them and creating a simultaneously different and unique voice at the same time. Layer by layer, broad washes of colour emerge which will become the bodies and, later, their voices. Rather than beginning a painting from a sketch, she invariably develops her compositions during a pictorial process that has already begun its journey. This method of “abstract metamorphosis” aims to lead the viewer's eye beyond the pictorial surface: "So, I always think of myself not as a straight figurative painter, but like a narrative formalist. Which means I need the paint, the materiality of the paint, to work as hard as the image is going to work. They need to go hand in hand, the content and materiality need to go hand in hand to create the painting and what it is trying to be. And so, the paint itself is trying to tell a story with how it's painted: the texture, the brushstroke, the gesture of the paint moving within a certain shape. And so, to me that is even more important than creating the image. And, if it's just image based I am not really interested in that. I am more interested in the paint doing the heavy lifting rather than the thing it's trying to be," she explains.

Born in Los Angeles and with a Ph.D. in Fine Arts from Yale, Hahn, now living in New York where she is Assistant Professor of Painting at Alfred University’s School of Art and Design, explains: "So, If I paint a face, it's more like: how is this texture being defined with the medium? How is it being defined with the mark making? How do the colours interact with each other to create that tension? And, I also think of residue in the painting, where everything is trying to be something that is a residue of a reality [How can paint mimic reality?] It's just paint. And the way the paint works to create this artifice, I am really interested in. And, I am really interested in these artificial components trying to make up a reality." Hahn never works from a preliminary drawing; she lets everything just happen and evolve after the first brushstroke, born of uncertainty, after which each character follows its own course and the oil paint guides the form: "In these works, the woman becomes a tool of visual seduction, the formal aspect of the paint delaying ownership over the content [...] I don’t know what exactly these women want to hide themselves away from, but I feel that it is necessary in order to really be seen, be themselves. Defined by the artifice of paint, they are untouchable, camouflaged by beauty and anonymous in profile. The works on paper also offer a respite from definition, the seriality leading to anonymity," says the painter. Hahn fell ill with COVID in April last year, at which time she felt the virus made her aware of being "just a body" up against the world. She admits to feeling scared and thinking that her body did not belong to her. She also thinks that, as a result, she found it more difficult to face her work: "I find it hard to put aside a pandemic and political unrest and carry on creating something that resides in an intellectual framework and trades in a formalism devoid of the present reality”. She adds: "I think the future of the art world will become insular. If you are a maker, you have the compulsion to make, regardless of if you are able to show it to the world".

Thus, the women who emerge from Hahn’s paintings no longer belong to the concrete world of people, having entered that other plane populated by figures made of texture, line, gesture and colour and in the form of moods.

Heidi Hahn

Some Other Sunset

Galería Fahrenheit

Justiniano, 8

Madrid 28004

19 de mayo 2021- 15 de julio 2021

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- Los atardeceres de Heidi Hahn en Madrid - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

London's Tate Modern is currently hosting a visit from a very different Van Gogh. The exhibition comes courtesy of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and includes a painting that seemingly brings with it the air of a Soviet billboard, a kind of propaganda, a punishment, a coldness. It is a far cry from Van Gogh's most iconic sun-soaked canvasses - no lilies, no sunflowers in vases, no wheatfields.

|

Colaborating author: Marina Valcárcel

|

|

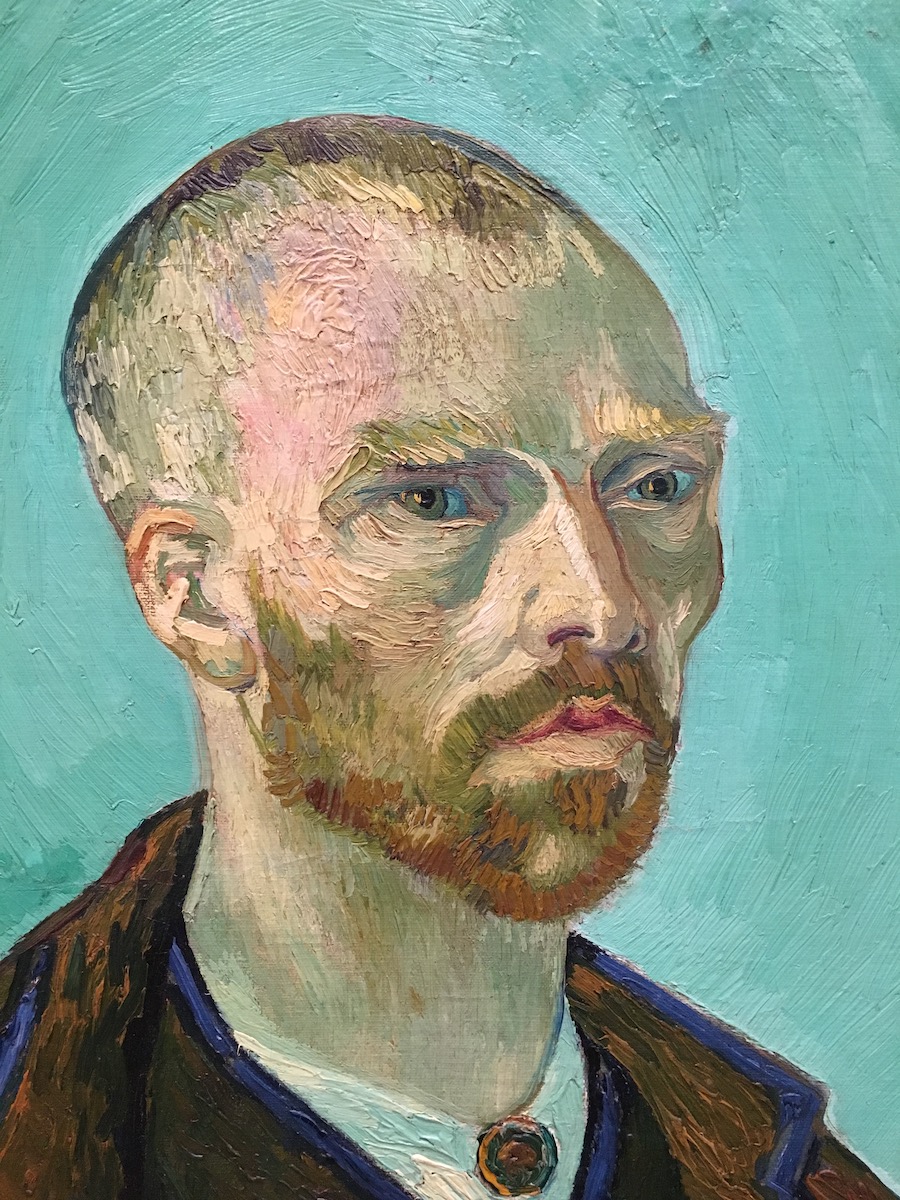

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-portrait dedicated to Gaugin (1888), Fogg Art Museum, USA

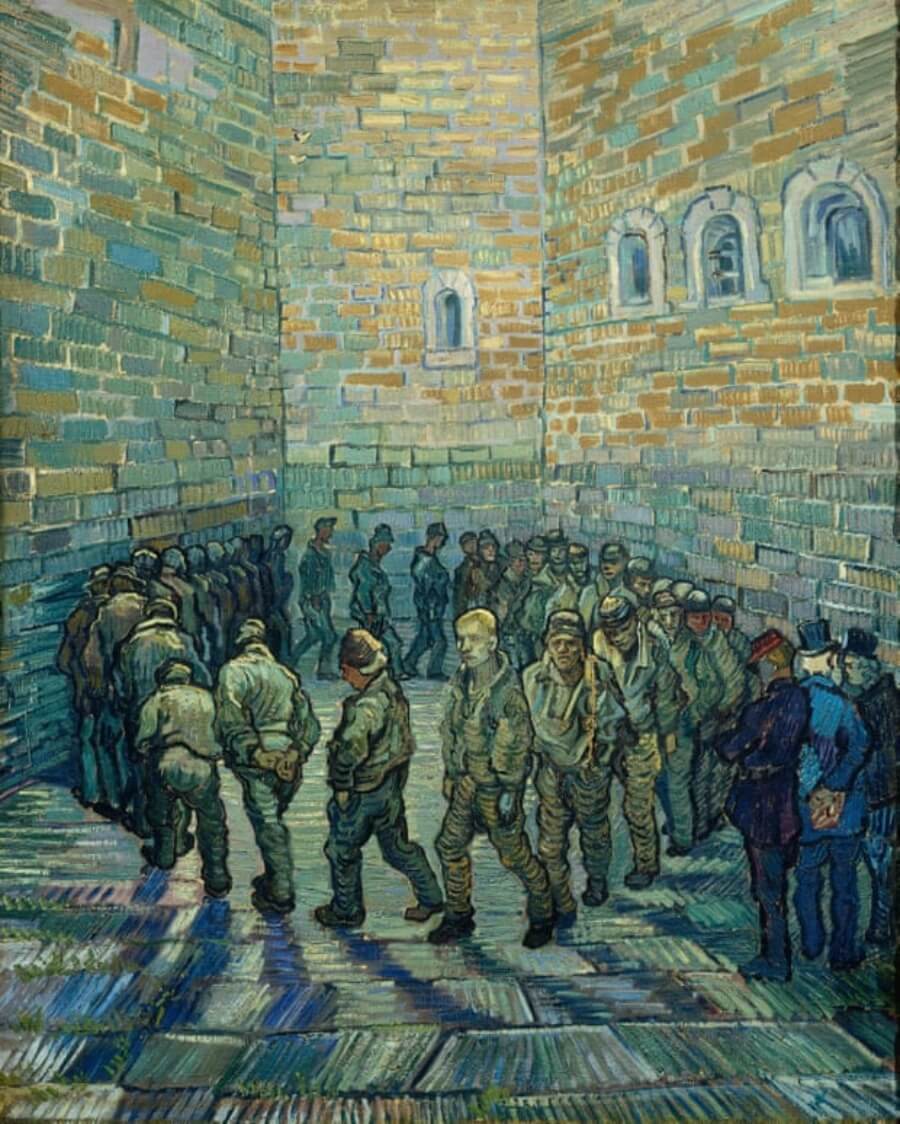

London's Tate Modern is currently hosting a visit from a very different Van Gogh. The exhibition comes courtesy of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and includes a painting that seemingly brings with it the air of a Soviet billboard, a kind of propaganda, a punishment, a coldness. It is a far cry from Van Gogh's most iconic sun-soaked canvasses - no lilies, no sunflowers in vases, no wheatfields. This is his most tragic painting and features a prison courtyard. Painted in February 1890, by which time Van Gogh was an inpatient at St Rémy asylum, rarely venturing outdoors to paint the countryside around him, instead feverishly reproducing the postcards his brother Theo sent him. This painting, based on an engraving by Gustave Doré, is a scream in the dark. It is his terror of madness and confinement. A group of 33 prisoners, heads down, drag their feet around a circle of oppressive and alienating exercise, enclosed inside a wall without end, two symbolic butterflies hiding between its bricks. A feeling of the absence of freedom permeates it. Only a small ray of light trickles down from an unseen sky to illuminate the face of one of the prisoners, the only one to lift his head and look at us. A blond-haired man, white-skinned. Vincent Van Gogh. On 27 July 1890, five months after completing this painting, he would go out into the wheatfields surrounding Auvers with a revolver and shoot a bullet into his stomach.

Vincent Van Gogh, Prison Courtyard (1890), Pushkin Museum, Moscow

A meditation on painting

Van Gogh died at the age of 37. Other visionaries who revolutionized the art of their time also died young - Basquiat at the age of 27, Egon Schiele 28, Modigliani 35, Raphael 36, Caravaggio 38 ...

Unlike them, however, Van Gogh's biography (1853–1890) stands out for something unusual - the bulk of his output came in the last two years of his life. Just over 700 days and 900 works that would blow the roof off Western painting. Two years in and out of hospital, devouring oil paint of the colour that obsessed him - yellow lead chromate. Making the most of any periods of calm for frantic painting, sometimes a picture a day, sometimes two, and battling the dazed stupor produced by the potassium bromide injected into his veins to prevent seizures. Painting so as not to go mad, painting every lily and every ear of wheat until his senses absorbed them, painting the sun and the moonlight, painting so as not to die, painting whilst dying.

In addition to his paintings, the Dutchman also left a key legacy - his correspondence, which has survived essentially intact to the present day. From August 1872 until his death, Van Gogh wrote over 800 letters, of which 668 were sent to Theo his younger brother, his confidant, accomplice, double. All of them begin "My dear Theo" and are written in Dutch, English or French.

This spring of 2019, all roads lead to Van Gogh: the Tate Modern has inaugurated its first exhibition dedicated to him since 1947 - Van Gogh in Britain - whilst the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is delighting visitors with a beautiful exhibition in which his landscapes dialogue with those of David Hockney. In Barcelona, there are long queues for the interactive Meet Van Gogh exhibition and Julian Schnabel's biopic - At Eternity's Gate - is still showing in cinemas.

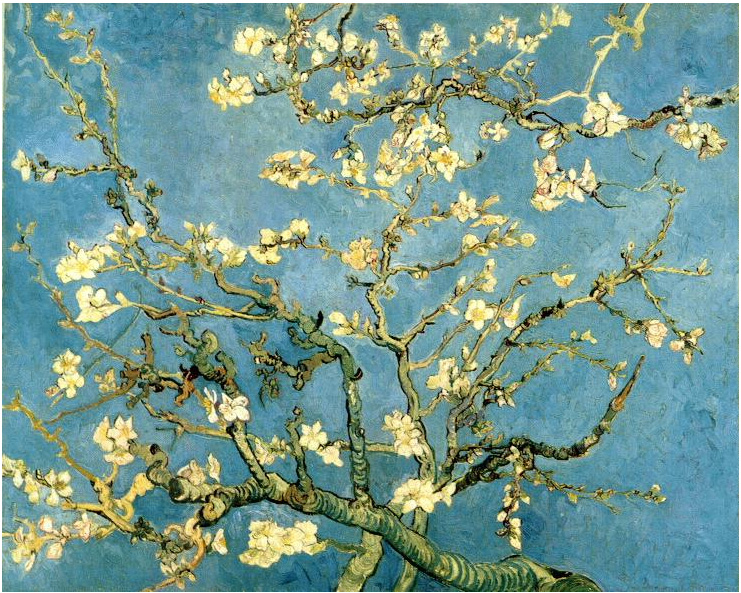

Vincent Van Gogh, Almond Blossoms (1890), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Holland

Long before Vincent picked a brush with the intention of learning to be a painter, he was already looking at the world through the eyes of an artist. As a child, he became practised at observing Nature during his long walks in the Brabant countryside: he examined birds' nests and wondered at the Dutch flatlands broken up only by the sharp spire of some church or by the red strip of sunset on the skyline.

Through his father, a Calvinist pastor from the Dutch town of Zundert, he was immersed in a traditional learning method then prevalent in northern Europe, namely, that everything we observe is full of metaphorical and symbolic meanings. Much of this teaching to children was done through the holy prints that surrounded them in their homes. In his father's studio hung three engravings that impacted Vincent as a child: The Return of the Prodigal Son, The Harvest and a baby in his cradle by Rembrandt; simple scenes that lit the flame of a profound religious sensitivity in Van Gogh from a very early age.

The search for salvation

Behind those blue eyes, Vincent's life revolved around the inner workings of his own mind. Long before art made its appearance, there was not only the need to seek his salvation but also a voracious amount of reading - the Bible first and foremost, along with Shakespeare, Dickens, Hugo, Homer and Balzac, to name but a few. Between the ages of 16 and 30, he and his brother Theo worked as assistants at the Goupil Art Gallery and travelled throughout Holland, London and Paris. It was in these cities that Van Gogh immersed himself in museums and galleries, deciphering the works of the painters he most admired: Rubens, Frans Hals, Delacroix and, of course, Rembrandt. In Paris, he encountered the Impressionists, Japanese prints with their bright colors and lack of perspective or shadow and the dotted brushstrokes of the Pointillists. And everything learnt from museums and books served to expand the treasure trove of images and memories he would carry with him like baggage.

At 30 and in less than a decade, this fragile and confused young man decides to learn to paint, assimilating all contemporary innovation and emerging as the pioneer of the most modern, expressive forms of painting. And so, in February 1888, Vincent boards the train to Arles where his painting would reach maturity while his life begins to fall apart. Living in the Yellow House and obsessed with Gaugin's arrival, he churns out, at the rate of sometimes six canvasses a day, his legendary paintings: the Sunflowers series, A Pair of Boots, Gaugin's Chair, his Bedroom in Arles ... the same room where he would soon be found dying. In Van Gogh As Prometheus, Georges Bataille asserts that it is precisely on the night in December 1888 that he handed over his severed ear at a brothel "... [w]hen his painting turns into lightning, explosion and flame; while at the same time he himself disintegrated in ecstasy before a beam of radiant light, exploding, on fire."

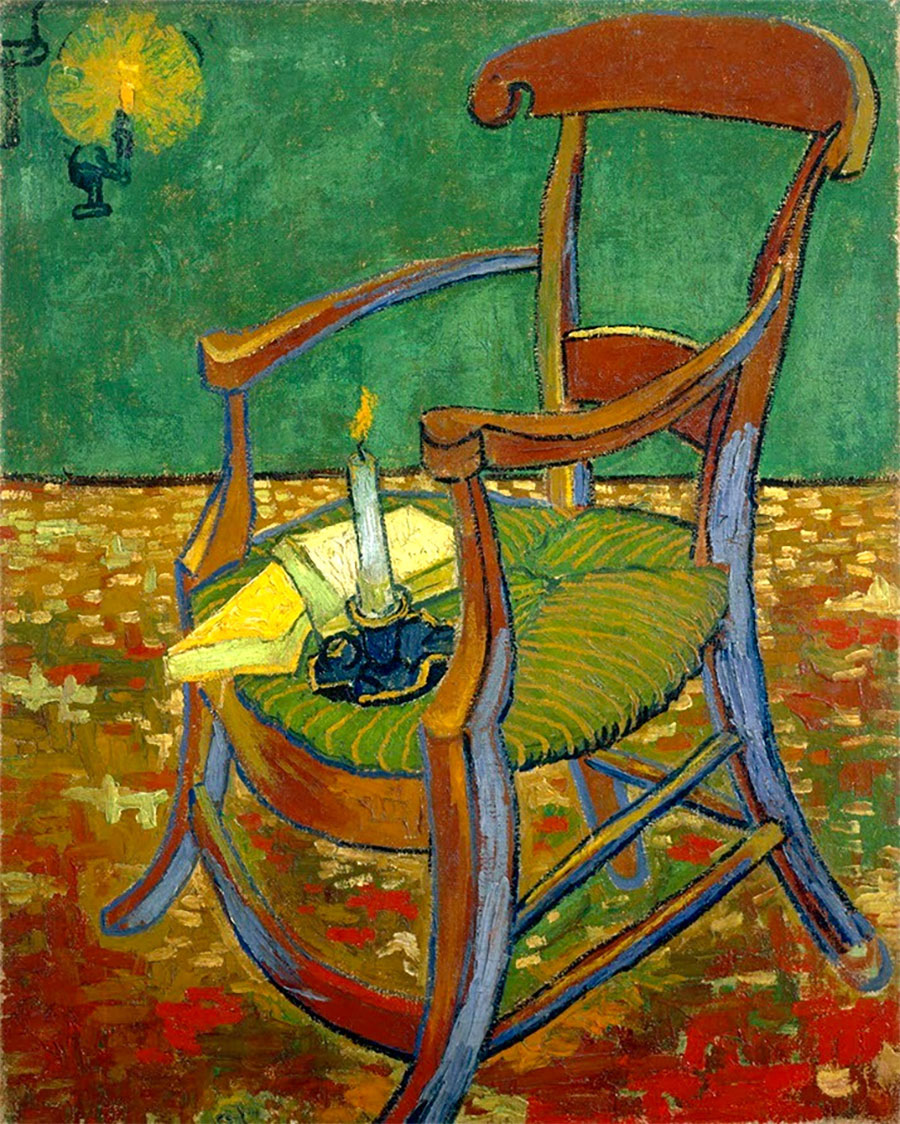

Vincent Van Gogh, Gaugin's Chair (1888). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Holland

Dawn of the collapsible paint tube

In Provence, he embraced the landscape, turning its abundant indigenous bamboo and reeds into brushes and pencils. He was also able to benefit from advances in the chemical industry as new colours appeared in the form of coal tar pigments, mauve and magenta aniline dyes and synthetic lacquer tints. But, more importantly, came the invention of the squeezable paint tube, which made painting with oil outdoors possible for the first time.

When he took his easel out into the countryside, he would turn his head like sunflowers in search of sunlight and colours, sensing nature in all its glory: temperatures, sounds, mistrals, scents ... and then falling into a state of hypnosis. The last snows had just washed the fruit trees in the orchards clean. There were paths and yet more paths lined with trees of all kinds and everything was starting to shine with an intensity that Vincent painted in short, stenographic lines. It was then that he discovered the motivation for his painting: in nature he found the power of suggestion in the colours he used to convey poetic ideas and to express feelings or moods. In his film, Julian Schnabel enables us to experience Van Gogh's catharsis through optical illusions. He recounts how one day, in a second-hand shop, he came across a pair of bifocal glasses. While wearing them, he realized that his field of vision was altered, blurred or expanded and believed he had hit upon how to convey on screen the artist's trancelike way of seeing the world.

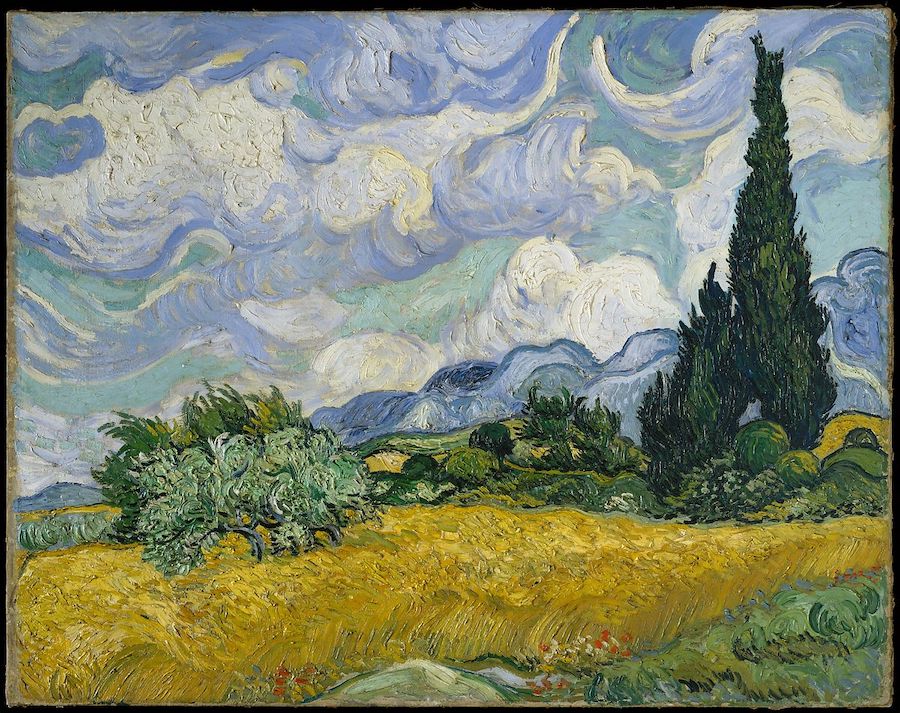

Vincent Van Gogh, A Wheatfield with Cypresses (1889). Metropolitan Museum, New York, USA

In Amsterdam recently, Hockney spoke with devotion: "I think my debt to Van Gogh is obvious here. For me, he's a contemporary artist. He still speaks to me today, like Brueghel." Van Gogh and Hockney lived a century apart but their landscapes, on display side by side, are like stars colliding: "Although it's obvious we both have a fascination with nature, what links me most to Van Gogh is not his colours, brushstrokes or landscapes, it's the clarity of his spaces." Insisting on their similarity of brushstroke, he replied with a smile: "Well, sometimes I steal things from Van Gogh. Great artists don't borrow, they steal." He added, seriously: "With a photograph, the whole surface is uniformly flat. Between a photo taken of a Van Gogh painting and the actual canvas, the difference is the brushstrokes. We can't look at a photo for long, no more than a fraction of a second, because we don't see the subject in layers. The portrait Lucian Freud painted of me required me to pose for 120 hours and that can all be seen in the layers of the painting. That's why it's of infinitely higher interest than a photo."

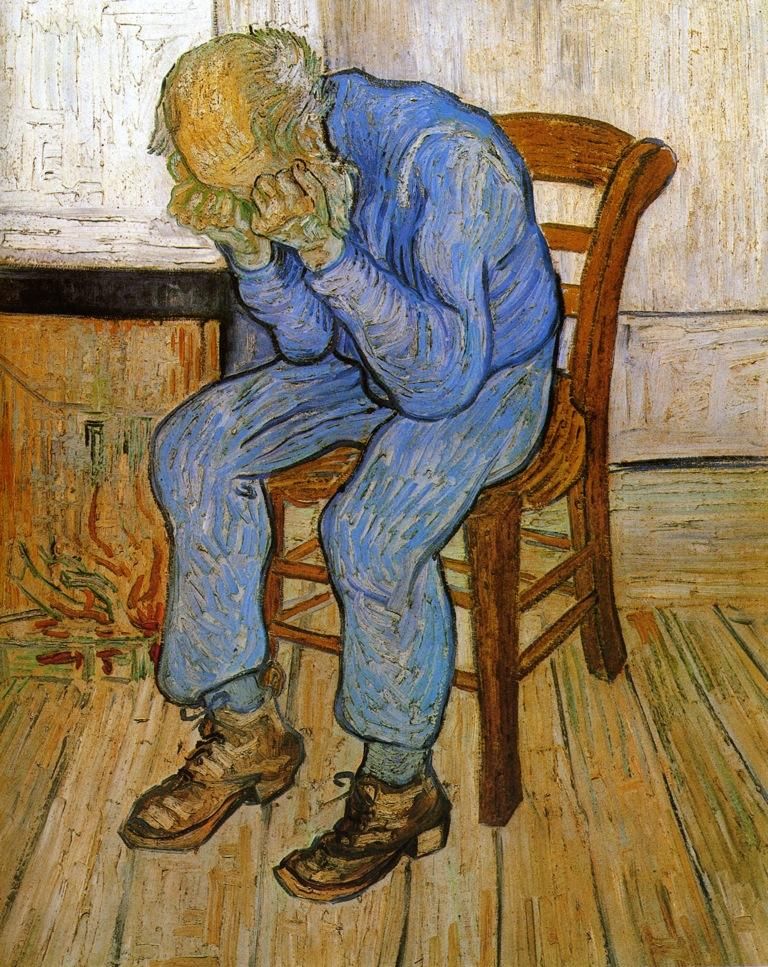

The London exhibition, the one in Amsterdam and Schnabel's film converge miraculously in one standout picture currently at the Tate Modern. It is At Eternity's Gate, the selfsame title as Schnabel's film. Along with The Prison Courtyard, Van Gogh painted it in April 1890 during his days of isolation at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum and this time it is based on a drawing of his from the Dutch period. It depicts a man sitting in a chair with his head buried in his hands. A symbol of despair and, more likely, of Van Gogh's own anguish. Two weeks before starting it, his doctor, Théophile Peyron, wrote to Theo: "He usually sits with his head in his hands and whenever someone comes to talk to him, it seems as if it causes him immense pain."

Conversely, for Hockney, At Eternity's Gate signifies a rebirth. In March 2013, one of his assistants, Dominique Elliot, committed suicide at the artist's house while he was painting the Yorkshire landscapes that are currently on display in Amsterdam. For several months, Hockney was unable to paint. In July of that same year, Hockney sent a drawing to his friend and curator Edith Devaney. It was a portrait of his friend Jean-Pierre Goncalves de Lima, sitting in his studio with his head in his hands. Devaney instantly spotted the similarities with Van Gogh's painting. Hockney acknowledged that this was not only a portrait of his friend but was also a kind of self-portrait in the face of tragedy. After that portrait came many more, which, in 2016, would become an exhibition at the Royal Academy: 82 Portraits and 1 Still Life. Van Gogh had persuaded Hockney to take up painting again.

Vincent Van Gogh, At Eternity’s Gate (1889). Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Holland

Silent contemplation

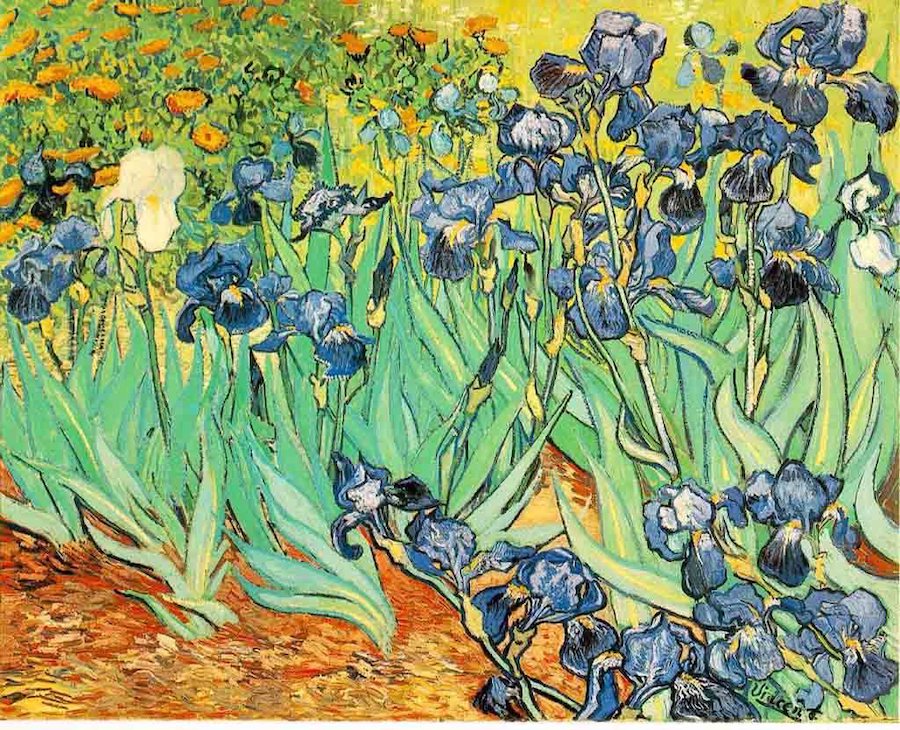

In 1890, during his confinement, Van Gogh found himself even more deeply affected by everything than before. He breathed every breath behind the bars and felt his spirit vibrate behind the window panes, letting it merge with the changing landscapes, light and seasons through his brushes. In the monastery's walled garden, he became a silent contemplator. Sitting under the trees, his eyes captured everything he saw. He would lie next to the lilies, face to face, and paint them, as if one of them, at one with them. When we look at his paintings today, we can almost feel the air, the freshness under the shade, the grass and lavender moving. Vincent wrote at the time that he was in his heaven.

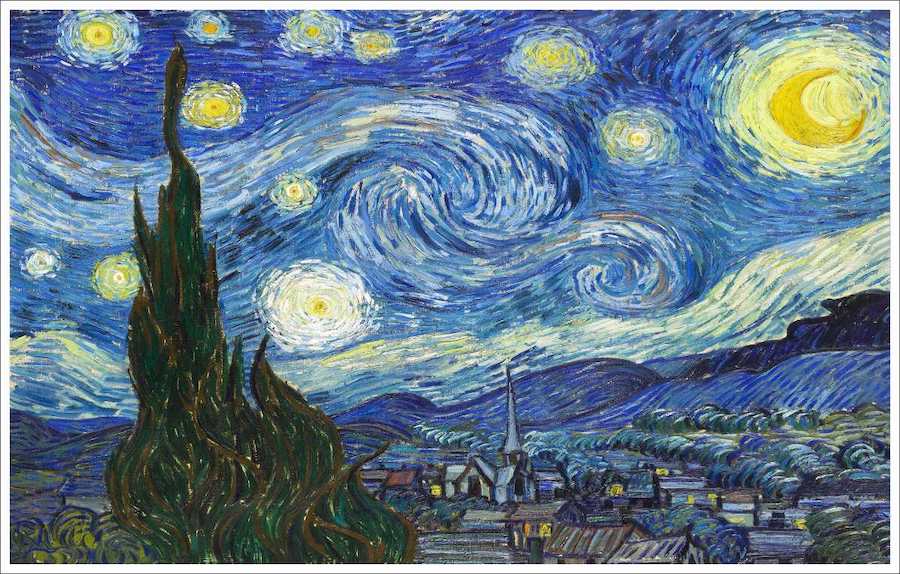

Vincent Van Gogh, Irises (1889). J.Paul Getty Museum, California, USA

However, towards the end of his life, the struggle inside his head between art and madness took on heroic proportions. The recurrence of crises was terrifying. In moments of calm, he painted furiously as if trying to ward off the next attack that would inevitably come the following day. For Van Gogh at this time, painting was both his destruction and at the same time his salvation, because it was precisely between episodes that he could see with greater intensity and lucidity and when his pictorial faculties seemed to be totally under control. These were works of wild abandon, painted on the edge of the abyss. Over and again, he painted barley-sugar cypresses like Solomon's columns, wheatfields with never-ending paths, starry night skies speckled as if by glistening gas lamps, cloud chains moving like ship sails tossed by the wind.

Vincent Van Gogh, Starry Night (1889). MoMA, New York, USA

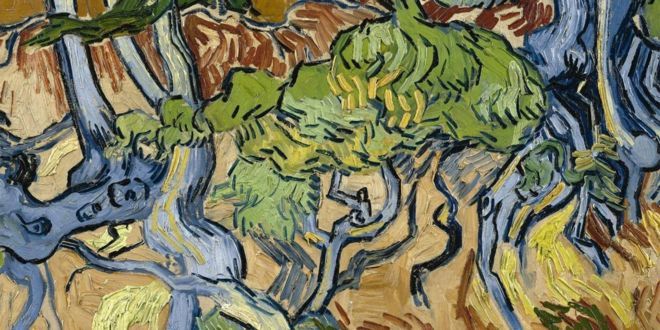

In May 1890, Theo knew that his brother was going through the most terrible time. He could see that Vincent was about to pull off a miracle and turn his mental disorder into a revolution. Theo feared that all of the internal intensity tormenting van Gogh was sure to explode inside his head once and for all. And he found a place for the explosion to be a controlled one - the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, 20 kilometres north of Paris. There, accompanied by Dr. Gachet, Van Gogh found the strength to unleash his final creative fury. Over the 70 days his spell in Auvers lasted, he produced 90 paintings. Many of them are his most exceptional works, almost always landscapes - solitary, disturbing and absolutely novel. His last painting, Three Roots, featured at the Amsterdam exhibition, is a manifesto to abstraction..

Vincent Van Gogh, Three Roots (1890). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Holland

In one of his last letters to Theo, Vincent lamented the fact that in the absence of any children of his own, his paintings would be his legacy. But Van Gogh did have a descendant - Expressionism. And along with it, many heirs - Kokoschka, De Kooning, Jackson Pollock ...

Within a few months, Theo, exhausted and ill, had lost his mind and also died. In 1914, his remains were moved to the cemetery in Auvers where he rests beside Vincent, with a matching headstone. From there, the two brothers observe Van Gogh's triumph - "Flowers die, mine will live on."

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

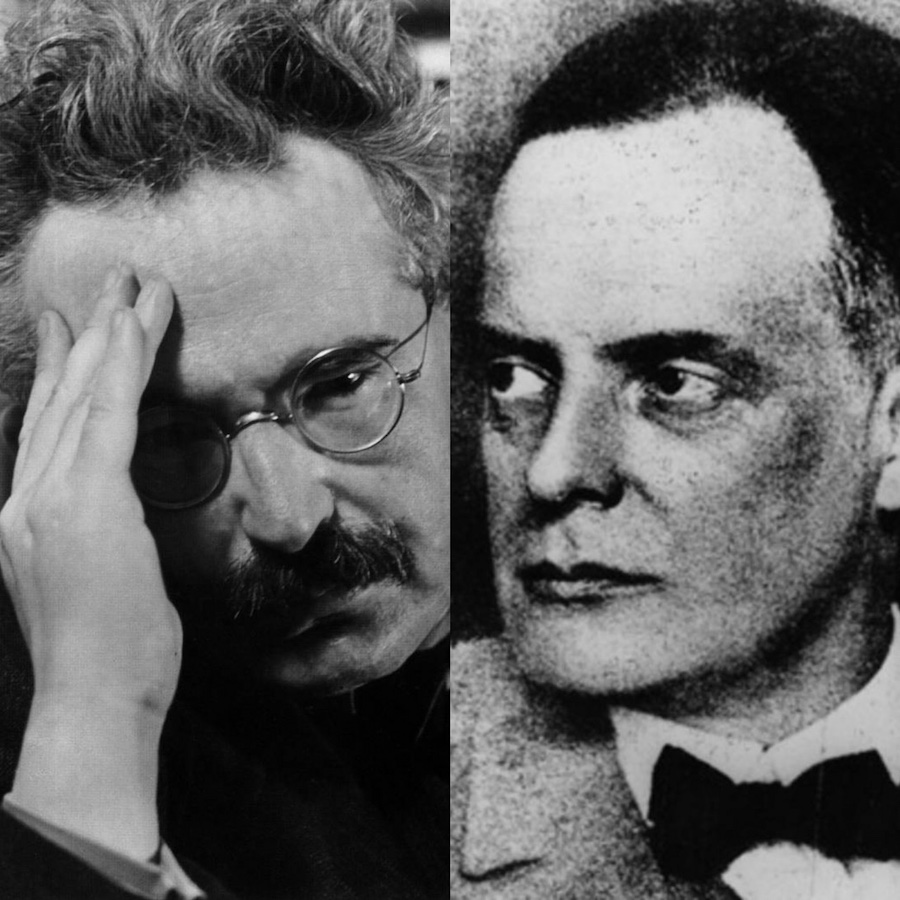

Two lives parallel in time, two like-minded ways of understanding the world and a piece of drawing paper that would forever bring together two of the great creatives of the first half of the 20th century. I refer to Paul Klee (1879-1940), Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and "Angelus Novus", a small work of art measuring just 32x24 cm and monoprinted in 1920.

|

Collaborating Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Angelus Novus

"Since Homer’s time, the greatest narratives have followed in the wake of great wars, and the greatest narrators have emerged from the ruins of devastated cities and landscapes.” H. Arendt

Two lives parallel in time, two like-minded ways of understanding the world and a piece of drawing paper that would forever bring together two of the great creatives of the first half of the 20th century. I refer to Paul Klee (1879-1940), Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and "Angelus Novus", a small work of art measuring just 32x24 cm and monoprinted in 1920.

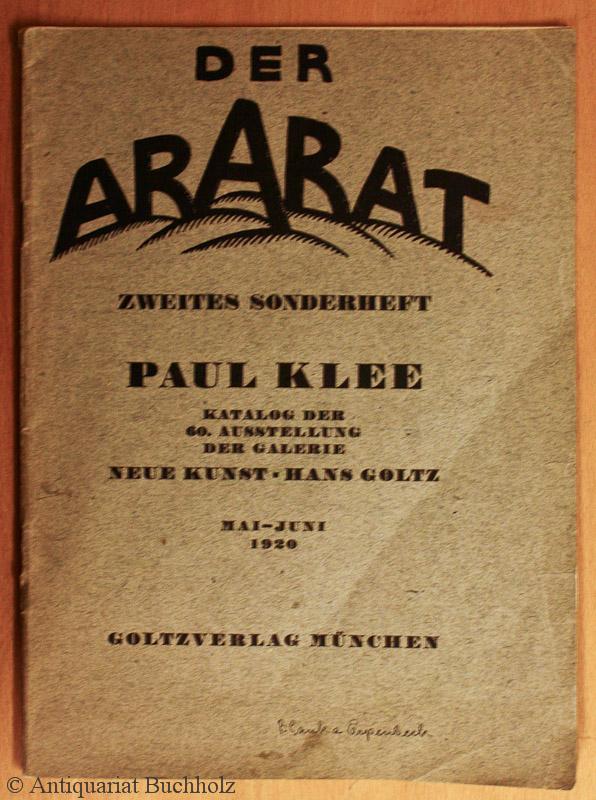

During a June 1921 visit to Munich, Walter Benjamin, accompanied by his long-time friend Gerschom Scholem, visited Hans Goltz's gallery on Odeonplatz to buy the "Angelus Novus", a painting that had had such a profound impact on him a year earlier in Berlin.

Klee had for some time been seeking out new ways to portray reality and new figurative possibilities. In his book "Creative Confession" of 1920, he begins by saying, "Art does not reproduce the visible, rather, it makes visible [what is invisible]." A tendency towards the abstract is inherent in linear expression and rightly so: graphic imagery confined to outlines has a fairytale quality whilst at the same time achieving great precision.

For Klee, form would become the catalyst element deriving naturally and directly from the imagination to unleash a new creative freedom aimed at expressiveness and immediacy. The figurative should blend with one’s conception of the world (1916). It is through the artist that Nature creates.

Angels, by definition of an uncorrupted nature, are a form of direct expression and an attempt to balance out the progressive, technological world with the spiritual world, of which Benjamin would later speak. They constitute a symbolic resource that captured the outrage he felt for all that was happening at a time of immense uncertainty in which certainties had lost their value. He needed to fantasize and angels were a means by which to go beyond a reality that was too prosaic. "To extricate myself from the ruins, I had to fly. And so I flew. In this shattered world, I only live in remembrance, just as sometimes one thinks of something from the past. That's why I'm abstract with memories" (1915). The same ruins that would later pile up at the feet of the 'angel of history'.

"The more terrible this world becomes, as is now the case, the more abstract art becomes." (1915). That year, his friend and fellow artist Franz Marc died on the Western Front at the Battle of Verdun. Klee and Benjamin shared a turbulent world that made its mark on their lives and work. They were both looking for a way to shape their thinking. For Klee, what we perceive is a proposition, a possibility, the authentic truth at its base, albeit invisible (1916). For Benjamin, the truth is in the most insignificant representations of reality.

“Something new is announced, the diabolical is inextricably linked with the celestial, dualism will not be treated as such but in its complementary unity. Conviction already exists. The diabolical is already peeking out here and there again, and it is impossible to suppress it. For truth demands the presence of all the elements as a whole." (10 June 1916). Again the image of the angel is conjured.

Benjamin gives us an account of his own interpretation of Klee's painting, without in any way compromising the artist's intentions regarding these images of contemporary angels that interested him so much and harboured so many ideas.

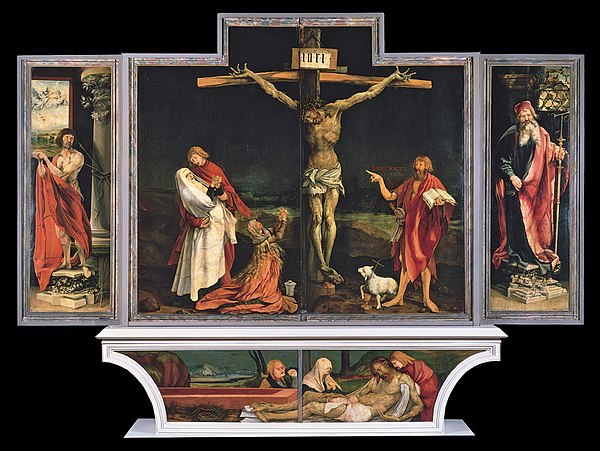

The "Angelus Novus" image became a recurring obsession in Benjamin's thinking. It always took pride of place in his studio and it seems he positioned it next to a reproduction of the Isenheim altarpiece by the German painter Mathias Grünewald, a work of tremendous drama that strips human misery bare. Might he have seen parallels between the two images?

The Crucifixion. Central panel of the Isenheim altarpiece. Matthias Grünewald. Museum of Unterlinden, Colmar, France

The head of the "Angelus Novus" is covered with strylised, curly hair and disproportionate to the size of its body. The feet resemble bird's claws and the wings are attached to the hands. The body houses a pendulum inside a tower ~ that harmonious and silent element marking movement and time that so intrigued Klee and so tormented Benjamin. Huge, wide-open eyes stare past us, to somewhere outside our field of vision. His mouth is half-open and it looks like he is about to say something. The "Angelus Novus" is bringing a message and awaits an answer through his outsize ears. Everything seems to fit for Benjamin ~ this is the Angel of History. Things reveal their significance to him in secret.

There is a painting by Klee called "Angelus Novus" depicting an angel contemplated and fixated on an object, slowly moving away from it. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth hangs open and his wings are outstretched. This is exactly how the Angel of History must look. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it at his feet. Much as he would like to pause for a moment, to awaken the dead and piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Heaven, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which he turns his back, while the heap of rubble in front grows sky-high. What we call progress is this storm.

This is the full text of thesis IX from "On the Concept of History", an essay comprising eighteen theses that constitute a reflection on the idea of progress and its consequences within the concept of history. This was a cornerstone of Walter Benjamin's thinking wherein he questions the era of modernity and the idea of progress it underpins, through one’s ability to give material form to the invisible. Written during his last months in Paris, on the eve of its German occupation, and concluded days before he left the city for a failed exile. His plan was to cross Spain into Portugal and there embark on route to the United States where his friends, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno and the Institute of Social Studies awaited him.

Deeply worried about an overly uncertain future and before leaving the French capital, Klee entrusted his friend George Bataille with a suitcase containing his most treasured possessions, the "Angelus Novus" and his latest writings, among them the manuscript of "Theses on the Philosophy of History", with instructions that, should anything happen to him, he would ensure they reached Theodor W. Adorno. The essay was published by Adorno in a special issue of the Institute of Social Studies in 1942, thanks to the copy that Benjamin had given to Hanna Arendt and which she, albeit reluctantly, passed on to Adorno. The painting ended up in the hands of Gerschom Scholem, at Benjamin's express wish. Scholem's book, "Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism", had been a fundamental inspiration for his work and is currently part of the Jerusalem Museum collection.

The "Angelus Novus" is an exceptional representation of the importance of movement in transformation and evolution and of the importance of looking to the past to build the future. The passage of time has only served to increase its powerfulness and seal its immortality.

Walter Benjamin and Paul Klee

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Paul Klee -Angelus Novus- Walter Benjam - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

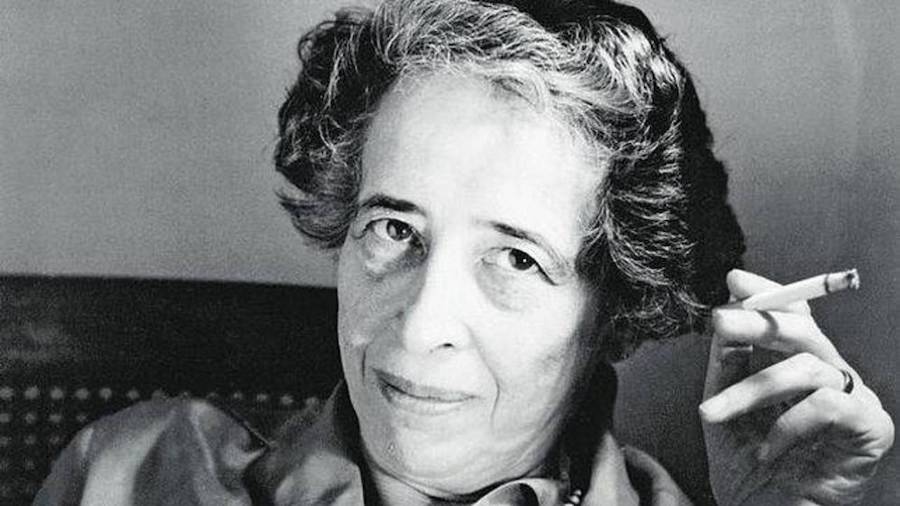

Until 18th October, Berlin's Museum of German History will be hosting the exhibition "Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century" which provides the perfect pretext to focus attention on one of the finest minds to have cut a swathe through the history of modern thought. The value of testimony from one of the freest thinkers in the field of political theory is all the greater since it comes from Arendt's own lived experience and is based on an absolute independence of reasoning over and above conventionalism of any kind.

Author: Elena Cué

Hannah Arendt

Until 18th October, Berlin's Museum of German History will be hosting the exhibition "Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century" which provides the perfect pretext to focus attention on one of the finest minds to have cut a swathe through the history of modern thought. The value of testimony from one of the freest thinkers in the field of political theory is all the greater since it comes from Arendt's own lived experience and is based on an absolute independence of reasoning over and above conventionalism of any kind.

It was this freedom of thought that led to the critical questioning of Arendt throughout a 20th century in turmoil. But it was also due to her thinking being a timeless, open discourse that lays no claim to being conclusive. Reluctant to see history as a continuous line of progress culminating in a conclusion, she thinks with critical vision from the present moment in time.

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), a German philosopher of Jewish origin, was the victim of anti-Semitism and the repression of a political totalitarianism that made her, first, stateless and later in the United States, a refugee deprived of legal or moral rights, a condition that made Jews, wherever they went, in her own words - "the scum of the earth".

The thinking of this leading figure in political theory is very difficult to label. She reflected in depth on the great, dauntingly complex issues of the 20th century such as anti-Semitism, the status of refugees, totalitarianism, Zionism, racial segregation in the US, student protests and feminism, all of which are analysed not only from what might have been the heights of an intellectual ivory tower but also from her own personal experience. Through objects, documents, articles, letters and family mementoes and even a section dedicated to her friends, this exhibition is an invitation to think for oneself, outside the box of any dominant discourse.

Hannah Arendt

- Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century - - Alejandra de Argos -