- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

If, in a nod to surrealism, Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) metamorphosed into something from one of his own photographs, it would most likely be a little turtle whose shell harboured a poetic soul. Since his first photographs in the 80's, of superimposed veins branching out over human forearms, his camera has never stopped capturing images of hum-drum, everyday objects as we've never seen them before coins, books, clocks, scales, tin-openers stripped of any and all superfluous connotations, objects whose reality he skews, sets free and offers to our imagination as simple signs, loosed from the chains of meaning. Madoz wants his images to slow us down and halt us in our tracks. He wants them so deeply imbedded in our minds and for so long that they become our very own. He wishes them "to always have something different to say to the person who wakes up with them on their wall every morning.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

If, in a nod to surrealism, Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) metamorphosed into something from one of his own photographs, it would most likely be a little turtle whose shell harboured a poetic soul.

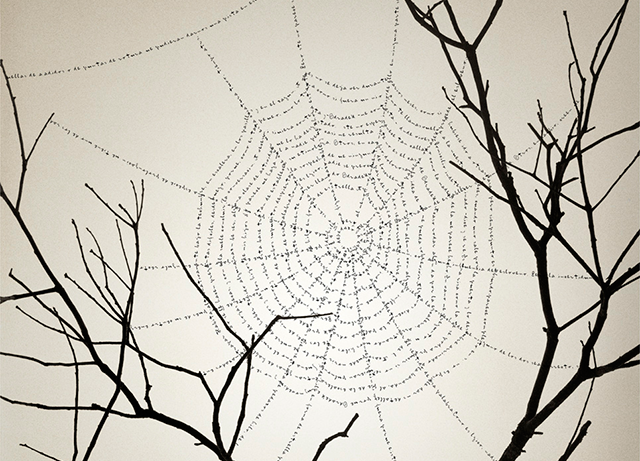

Since his first photographs in the 80's, of superimposed veins branching out over human forearms, his camera has never stopped capturing images of hum-drum, everyday objects as we've never seen them before coins, books, clocks, scales, tin-openers stripped of any and all superfluous connotations, objects whose reality he skews, sets free and offers to our imagination as simple signs, loosed from the chains of meaning.

Madoz wants his images to slow us down and halt us in our tracks. He wants them so deeply imbedded in our minds and for so long that they become our very own. He wishes them "to always have something different to say to the person who wakes up with them on their wall every morning. To never wear out". And it was from this poetic wordplay, this expressivity, this expansion of meaning that his exhibition Chema Madoz 2008-2014: The Rules of the Game came into being. But also as a homage to the Renoir film of the same name.

While we wait for Madoz, who is patiently dealing with the media days before its inauguration at Sala Alcalá 31 in Madrid, we have a chat with the event’s organizer Borja Casani who tells us: "Chema's photos are, ultimately, the photographic portrait of an idea".

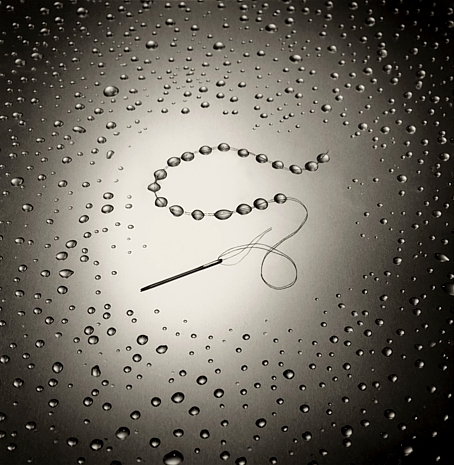

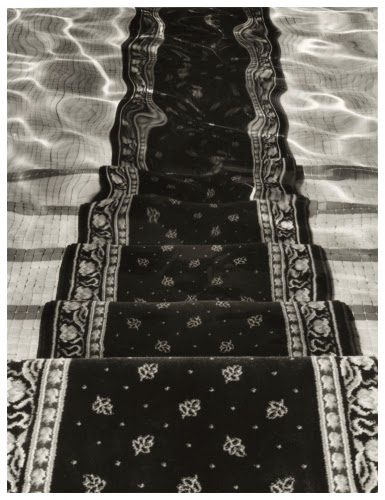

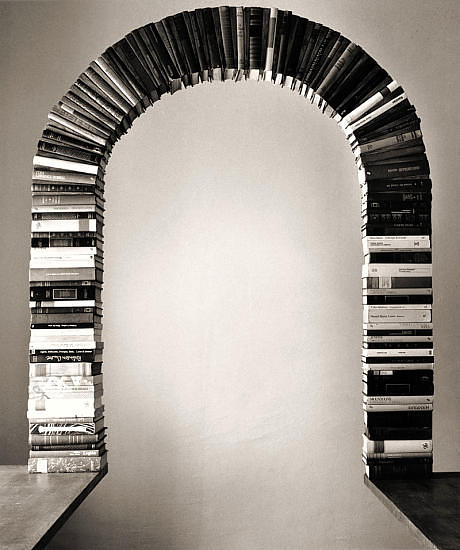

If objects had souls, Madoz would be the one to portray them. He is a seeker of simplicity. He lays all things bare, his aim being to achieve an image that is "austere, almost monastic in its frugality". That's his way of understanding beauty, interpreting it and then offering it to the spectator's imagination, divested of its usual meaning: books built up as the voussoirs and keystones of an arch, water droplets threaded onto a necklace of aqua pearls, a glass watch, an astral card, ... Casani goes on to say: "With Madoz, what you get is a hieroglyph that is already deciphered. He reveals to us a hypothesis and what then happens is that people feel comforted by the fact that they understand it. He presents us with objects we all feel familiar with. They're everyday items to an African, a European or a Latin American. And from this point of view, it's really satisfying to see Chema's success in so many countries. We've exhibited in, for instance, Egypt and people there understood. It's so gratifying, seeing day-to-day objects on display and communicating something to us."

Madoz arrives and what strikes us is his gaze. Shy but scrutinizing at the same time, taking everything in, from top to bottom, fixing on and dissecting whatever grabs the attention of his mind's eye at that moment, lodging itself there, nagging at him until finally it makes its way into one of one of his sketch books in the form of a drawing. And from those pages into an almost surgical transformation on an operating table come carpentry bench where a woodwork square and tools become the sails of a toy boat or the grille bars of an iron door contort themselves into musical notes.

Madoz speaks slowly. He likes a slow rhythm. And silence. These are requisite traits in someone who observes the minute details differently, just as children absorbed in contemplation of an anthill invent a make-believe world around it. "I was an only child and I got used to playing all by myself very early on. I do like people but I need my solitude, too."

Following earlier exhibitions (Reina Sofia Museum, 1999; Telefonica Foundation, 2006) and Spain’s National Photography Prize (2000), the Sala Alcalá 31 exhibit is a compilation of Madoz's work over the previous 6 years, all invariably in black and white, analogue, and on baryta-coated paper, hung side by side under the dome of a basilica-like building that once housed a bank. Curiously, it was Madoz's first ever and much-despised job in a bank that caused the existential crisis that eventually freed him to devote himself full-time to photography.

The harmony of blacks, whites and greys along with the sheer Madrid sunlight flooding the gallery combine to create the very sensation of calm and silence that the artist intended. He would like his audience's attitude to be one of measured serenity, like the reading of a haiku. "This space is wonderful, if a little complicated by so many columns. What Borja and I tried to create here is a simple, elemental setting that "breathes", which I think, happily, we achieved with just the three divisions that permit a certain repose and tranquillity."

Whilst talking to us, Madoz is drawn to specific photographs and we follow him, observing his choices. There have been a few tangents during his evolution as an artist, albeit subtle ones because the crux of his language has always remained intact: everything hinges on and revolves around the object itself, and always will. However, in this exhibition, he adds or extends some personal obsessions, namely; his passion for calligraphy and the written word; the as yet timid appearance of some pencil drawings; and animal figures. Incidentally, over the course of his trajectory, he has dropped the human portraits from his field of interest due to the fact that, by stripping away their entire identity, their very selves, all he reduced them to in the end was a kind of pretext.

Now, though, he replaces them with mannequins: St Sebastian on a pillar, pierced by arrows that are better known to us as acupuncture needles or the two hollow, wax, pianist-like hands of a woman, their fingers twisting a thread of letters into a geometric puzzle; a reminder of that childhood pastime whereby two friends face to face, and their twenty fingers, manipulate one long piece of taut string into myriad patterns.

This latter photograph serves as the perfect example to ask Madoz about the very many ways his work could be interpreted. Echoing Joseph Beuys’ views on his approach to the creative process : "I've always been interested in creating images that don't 'wear out' even though they're constantly there, visible; images that, despite being viewed on a daily basis, keep enticing you back up close, again and again, making you re-possess them time after time. When you speak of that paused rhythm, that's the rhythm at which I approach the artists who interest me and whose work affects me on a very personal level. To think that your own work might have that effect on someone else is wonderful.” So we talk more about paintings. Madoz admits to a soft spot for Magritte: the clouds, the bowler hats … but also De Chirico and Morandi.

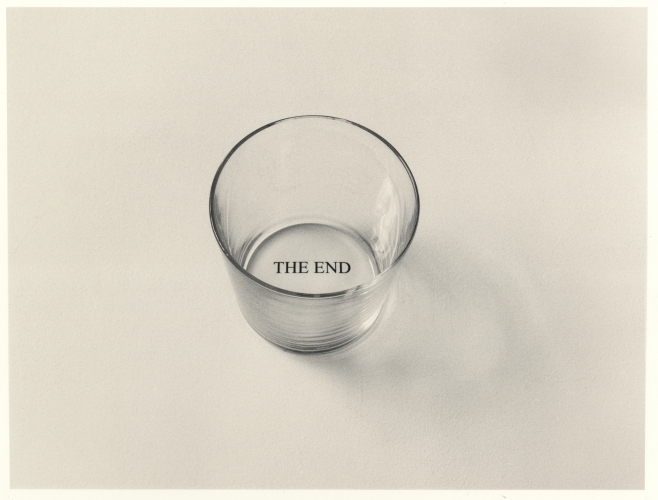

And then he confesses to another partiality: "There's one photo in the exhibition, just an empty glass tumbler on a white background and inside it is written The End. I think it's a lovely photo. The beauty of it and the glow of the glass really move me. And it’s that simplicity that leads, ultimately, to something beautiful. They’re very simple scenarios montages, lit from side on, the object effectively laid bare for us and within our reach. Nevertheless, it isn’t the beauty of a flower that’s being appropriated, or what is generally considered to be beautiful, or whatever represents the idea of beauty."

From painting, we move on to literature: "It's about the ability of verbal language to give us visual images. Gómez de la Serna would be, for instance, an obvious example but also Jorge Luis Borges, Bioy Casares, Boris Vian and Tanizaki. All of them, consummate writers with very personal imaginary worlds."

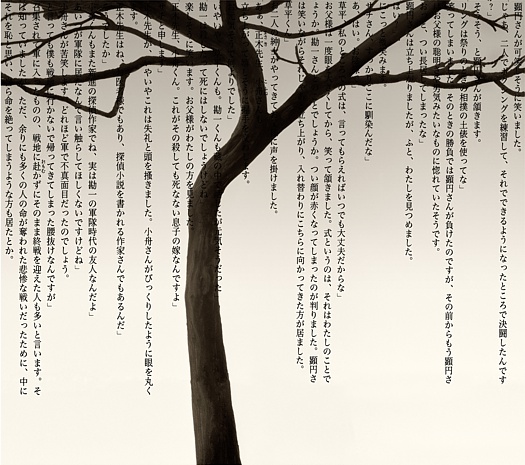

Madoz's studio is a suite of rooms not unlike a treasure trove or Borges’ The Aleph: “a point in space and time that contains all spaces and all time”, his micro cosmos of enough items and ideas to last him an entire lifetime. Out of them all, there's one to which he returns again and again and always will, one that plays on his mind in a never-ending loop: "Books. So simple, so quintessential, that rectangle offering so many possibilities, such varied interpretations and points of view, such depths of semantic richness. That's why you’ll find them so consistently and repeatedly throughout my life’s work. But I always get the sinking feeling that, maybe, one day, I'll run out of ways to use them, not because there are no other uses but because of my own lack of ability. I have my limits but the possibilities of the objects themselves are endless.” We stop now to face a picture of a map in which there appears to be the silhouette of a fish. It's one of his photos that have been heavily influenced by Japanese prints: "It's two negatives, one on top of the other; one is the map lit from above and the other is the fish sketch; and then I projected them both together." They start to resemble animals or animal shadows. Beside this is a picture of the grains and rings of a tree trunk marked out with letters, which confirms the importance of not only the written word but the whole realm of literature to Madoz. He never titles his work: "I have too much respect for writing. I well know a title can give a suggestive dimension to the reading of a piece. I, however, prefer not to give any clues at all and thereby give free rein to the spectator’s interpretative possibilities.”

The art of capturing an object’s essence begins, for Madoz, with the search for it. He is a regular at Madrid’s open-air flea markets where he often finds himself as if overcome by a feeling of stalking the prey that’s been snooping around his subconscious for some time previously. So what causes these “light bulb moments”? "It’s the mystery. I sometimes come across objects that are, essentially, weird. It’s more like them making me feel unsettled and confused. Something tells me to acquire them and make something of them and, generally-speaking, that’s what I end up doing.”

Madoz lives surrounded by the subjects he photographs, as does Kemal, the protagonist of Orhan Pamuk’s novel “The Museum Of Innocence”, who steals everyday household items from the woman he is stubbornly in love with only to make a museum out of them. Madoz, however, is not keen on following in the wake of the trend set in the 1920’s and 30’s by the likes of André Breton and, even more so, Marcel Duchamp during his ‘readymade’ period – a trend whereby the object gets top billing in the art world and has exhibitions to show for it. "I’ve always felt that photography places these objects in a much more attractive and interesting setting. Somewhat like a dream state. Something in your mind or on your mind that’s difficult to put your finger on, intangible. I really like that distance.”

He is well used to living with the objects he’s photographed. They are part and parcel of his predilection: "I’m surrounded by them in my studio. I store them there, often exactly as they were when photographed and sometimes as re-usable material. It’s quite amazing the significance and implications that objects have and how we endow them with powers of evocation. We associate them with life events, moments in time, people and ideas. For me, this was a huge discovery when I first started working with them. I remember once finding a badge I used to wear at school and I was amazed at how it transported me right back to my classmates, even my old desk …”

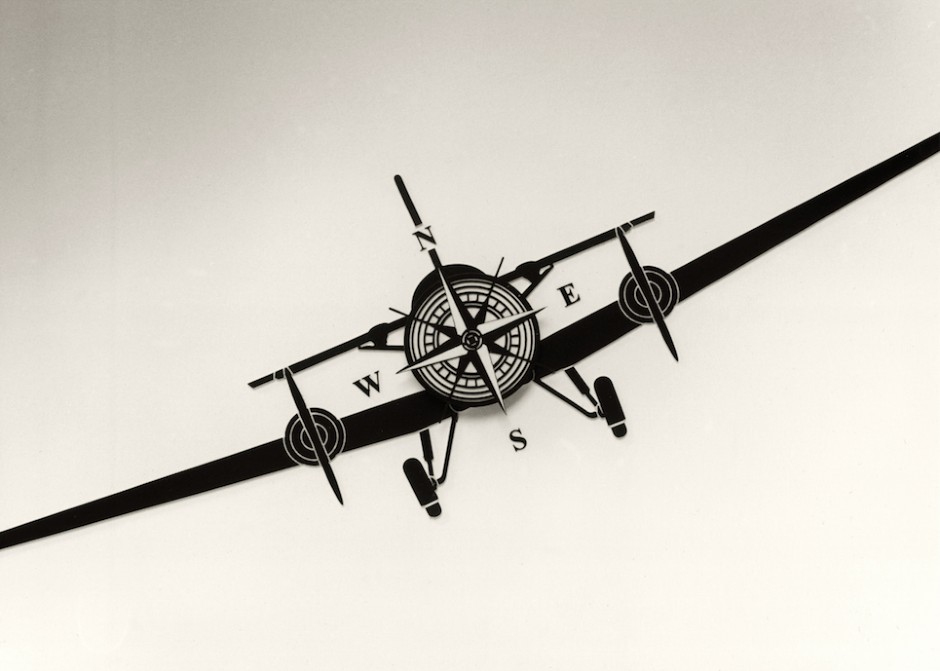

And so we finish our guided tour with the photograph that Madoz considers his most representative. It’s one of a lightplane seemingly made out of a child’s self-assembly cut-outs, black against a white background. Childhood here hinted at as a magical time of creation. On its propellers, Madoz has placed a compass: "At times, I identify with it. It corresponds to my mood; my being always on the move, somewhat disorientated.” And here is where our artist resides, between imagination and contemplation: Chema Madoz, a photographer of few words.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Chema Madoz. A photographer of few words - -Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Paris is paying tribute to Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), one of the most distinguished artists of the 18th and 19th centuries, by according her a magnificent retrospective at the Grand Palais until 11th January 2016. Over 160 oil paintings, pastels, sketches and drawings are on display to illustrate the life’s work of this remarkably gifted painter who dazzled Europe’s finest with her mastery. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun is arguably one of the few women artists given the attention and recognition they deserve, a rarity as "women's art" has traditionally been paid scant regard. Her reputation could even be said to have reached legendary status in art history, the praise during her lifetime and the wealth of critical acclaim ever since never having diminished over the years.

|

Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Paris is paying tribute to Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), one of the most distinguished artists of the 18th and 19th centuries, by according her a magnificent retrospective at the Grand Palais until 11th January 2016. Over 160 oil paintings, pastels, sketches and drawings are on display to illustrate the life’s work of this remarkably gifted painter who dazzled Europe’s finest with her mastery.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun is arguably one of the few women artists given the attention and recognition they deserve, a rarity as "women's art" has traditionally been paid scant regard. Her reputation could even be said to have reached legendary status in art history, the praise during her lifetime and the wealth of critical acclaim ever since never having diminished over the years. Her tumultuous existence make her an especially appealing personality. High society chic during the Ancien Regime, counting down the hours before the French Revolution, the toast of the most exclusive European royal courts of her time and, when she returned to Paris after a long exile, the Napoleonic Empire at her feet. Always conscious of her own talent, she managed to assert herself in a man’s world and deploy the full arsenal of weapons at her disposal to forge herself a niche in an art world dominated by men. With consummate subtlety, she used her own attractive likeness as propaganda for her skill as a portrait artist, with many of her self-portraits revealing the genius, beauty and vitality of this woman determined to reach the top.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée, born in 1755 into an artistic Parisian family, where her father Louis Vigee, a renowned portrait and pastel painter, introduced his daughter very early to the profession. At fifteen, she began her career as a portraitist and in 1774 enrolled at the Saint Luc Academy where her first works were exhibited. Her marriage to the art dealer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun opened new doors and paths to recognition for her. She studied the Old Masters and steeped herself in all styles of art for inspiration. In 1778 she painted the first in a long series of portraits of Marie Antoinette, to which she owed her initial fame, and it was this close relationship with the Queen that helped secure her a fully-fledged membership of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1783. Her first portraits exhibition at the Academy was not received unreservedly but she soon won over her critics and the public. In 1785, her large canvas, "Marie Antoinette With Her Children" caused such envy amongst her detractors they instigated a campaign of criticism and libel against her. Although she defended herself ably, her character had been so effectively undermined as to force her to abandon her natal Paris at the onset of the Revolution and begin a long pilgrimage across Europe.

Her first years in exile were spent all over Italy. Turin, Parma, Florence, Venice, Rome and Naples, to name just a few, were the cities where she lived distanced from her world, a world that would never be the same again. Her fame preceded her and, with that, Italian aristocratic and artistic circles opened their doors and welcomed in the renowned French portrait artist. There being no sign of a possible return to Paris, her exile would continue on for many more years. In 1792, she relocated to Vienna, to work for exiled French aristocrats and for the Austrian and Polish nobilities. In 1795, she travelled to Russia and settled in Saint Petersburg. The court of Queen Catherine II received her enthusiastically and for the next six years she would work there tirelessly and bring about a new understanding of the art of portraiture. Her work received official recognition from the Saint Petersburg Academy of Fines Arts and she was again rewarded with the support of both fellow artists and the public alike. During these upwards of 12 international years, her fame and fortune grew substantially, allowing her a freedom rarely afforded a woman of that era. On the 18th of January 1802 she returned, finally and definitively, to Paris where she would remain for the rest of her life, bar a few trips to England and Switzerland. Her work rate was prolific as she battled and managed to maintain her fame and prestige within Europe’s most exclusive artistic circles. Her salons were where the most illustrious of the day would meet: painters, writers, and philosophers. The passage of time did not diminish her artistic fervour or curiosity as she devoted most of her time to nuancing the art of landscape painting, then made very fashionable by the arrival of Romanticism. A few years before her death, she wrote her Memoirs: three volumes recording the experiences of a life lived to the full, without compromise or complaint. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun died in Paris in 1842 at the age of 86.

Vigée Le Brun's compositions are refined, full of beauty, brimming with life, replete with expressivity and colour innovation that leave no doubt as to the sophistication of her technique. Her portraits are the reflection of a whole era and an unbounded source of research into the ideal woman she herself embodies. Rather than breaking from the stereotypes of the time, her subjects go beyond purely pictorial representation. The poses and gestures of each of her models highlight the importance of her paintings in the study of an entire era. Nothing is depicted by chance. Every scene conceals a multitude of details with a life of their own quite apart from the overt composition. Her work served as a reference point for other painters as she tweaked and customized her themes with the changing times. Examples of this include her allegorical and mythological paintings in the neoclassical style; her Rousseau-influenced paintings of maternal and filial love; and a comprehensive gallery of beautiful and sensual women, each perfectly adapted to her time and place.

One cannot talk of Vigée Le Brun without referencing another great Parisian artist, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1813), who shared her passion for "the easel" and her struggle for recognition in a male-dominated artworld. Both started on the same day at the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture and, due to the similarity of their styles, were constantly compared with each other but, although Labille-Guiard never achieved the international fame her contemporary enjoyed, she did still forge a niche for herself and earn well-deserved recognition for her historical and portrait paintings, along with much success as a teacher. After working at the court of Louis XVI, she reinvented her paintbrushes, adapting them to the new revolucionary times and continued to paint for the rest of her life.

Vigée Le Brun's and Labille-Guiard’s works made a massive contribution to the promotion of Fine Art studies amongst later generations of women artists and demonstrated that the fact of being female was no barrier to expressing one's talent and creativity in a male-dominated world. Both women had presence and visibility in both private and public spheres, brilliant women whose forthright personalities, in a universe dictated by men, revealed a hitherto inconceivable and unheard of reality.

The Vigée Lebrun exhibition is the perfect opportunity to reflect on women in art and to examine the liaison between reality and painting as a mirror reflexion of our world. Her persona represents those same ideals that, many years later, Virginia Woolf would broach in A Room Of My Own, namely: personal and intellectual liberty coupled with an economic independence that could break the bonds of established convention.

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

This little journey begins on a wall. As dusk falls, so begins a dialogue between that wall and a window, a transparent, vertical frame that reflects in the Swiss meadows outside and surrounding the Beyeler Foundation, all fresh, serene, rose-tinted; set against the electrical charge of a horizontal canvas turned into a muted scream depicting the Wailing Wall. It’s Ernst Beyeler and Renzo Piano in the company of Marlene Dumas. One of those rare moments for meditation: architecture resting its hand on the small of the painting’s back to guide it through a perfectly synchronised, beautifully choreographed dance.

Ernst Beyeler was one of the greatest ever art dealers, In 1970, along with Trudl Bruckner and Balz Hilt, he created the Art Basel fair. He and his wife Hildy aquired a world-class collection of masterpieces and commissioned the architect Renzo Piano to design an exquisitely beautiful museum in which to house them. It opened in 1997 not only to exhibit the Beyeler’s own private collection but also to showcase the world's most important contemporary art exhibitions.

Until 6th September 2015, the Beyeler Foundation museum was the venue for Marlene Dumas’ The Image As Burden, a retrospective of 40 years worth of work comprising over a hundred pieces.

Broken White, 2006.

The Burden of Apartheid

Marlene Dumas (Cape Town, 1953) is an artist who sails deep through the swell of waves and dense, eclectic backdrop that is her work, and very much at odds with her physical appearance it is, too. She is slight of build, bubbly, with playfully expressive pale blue eyes, a booming laugh and a fresh-seeming joie de vivre

But behind that facade, Dumas is a tireless worker and avid collector of postcards since early childhood and still, even today, in her untidily tidy Amsterdam studio, she has everything filed, ordered and catalogued. Dumas, whose figurative style centres the human face and the human body, never works from a live model. She invariably works from a flat, printed, two-dimentional image. Her sources are the hundreds of thousands of photographs cut from newspapers, magazines, some of them pornographic, books on the mentally ill, the “lunatics”: a word she says she likes because of its association with the moon’s influence on our states of mind, catwalk models, “I cannot conceive of a trip without Time magazine”, pamphlets, art postcards and, most of all, her own polaroids. “One could say that South Africa is my content and Holland my form. And I think, as well, that the images I use are universal, known to everyone. I deal in second-hand images and first-hand experiences. My models have already been moulded and posed previously by somebody else. There are no virgins here.” she insists.

Mamá Roma, 2012.

Dumas paints from a place of condensed reality. Hers is painting that questions. Or targets with the precision of a dart. Expression, mystery, the connection between public and private, dreams and reality. Take that portrait in blue of Amy Winehouse. Isolated figures, usually with no background, abandoned in the solitude of a canvas and its sadness.

Dumas is fully aware of the power of the photography and films she has been addicted to her whole life. It was from celluloid, and the looks to camera of its actors, that she learned the rules of imagination. She knows she must surpass the magic of photography and magnify the power of the filmed image in order to justify painting them. This is the motive behind her characteristic focus: the zoom button here, a close-up there, chopping and cropping into strange dimensions. See her paintings of gigantic babies. “I’ve never had the first clue about the actual size of a head. Anatomy never interested me.” she says.

Amy-Blue, 2011.

Her themes are extreme and recurrent: death in multiple aspects and facets. Paintings such as The Kiss (2003), Lucy, Stern and Alfa (2004) are large canvases of dead, apparently serene, women. They are oil on canvas but have a strange, aqueous, veil-like consistency, as if the contours and the colours of these heads were seen through the filter of a memory, dream or nightmare. Violent deaths: Dead Marilyn (2008) or Dead Girl (2002), the head of a young Palestinian girl falling down lifeless, killed. The death of the Dutch film director Theo van Gogh or a dead swan, its sinewy neck and unfurled wing white against a black background.

The Swan, 2005.

And then there is race, above all else, race: its message, its meaning, Dumas’ use of the colour black. Racism that stretches from Apartheid to the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem. The Wall (2009), The Widow (2013). Dumas inherited from Gerhard Richter an interest in “series” painting and also, by the same token, an interest in hanging pictures in such a way as for them to be grouped together in rooms by theme. She is able to fill whole spaces with hundreds of drawings of little tiny heads in black and white, each one unique and distinguishable if only from its expression. There have been multiple series sets since Models (1994) up to and including her latest and as yet unfinished Great Men (2014).

Models, 1994.

At a time in Madrid when the memory of Zurbarán’s Christ and Van der Weyden’s recent departure are still fresh in our minds, the two series of Crucifictions and the portraits of Christ in Dumas’ The Perfect Lover are akin to questions. Van der Weyden’s St John, desolate at the foot of the cross in the 3 metre high Calvary, was powerful but were there ever any Christs as abandoned to their solitude as Dumas’ Gravitá (2012), or Solo the year before?

Gravitá (detail) 2012.

And at the other extreme, her pornography series: strippers, nightlife, neon lights, young men in explicit poses, young girls midway between innocence and abuse, leather boots, black stockings ...

"I paint because I’m a woman” she says. “I’ve always wondered why the great themes of life and love must be conceeded to film directors, authors or pop stars. I want to paint all of that, too.” And her pictures became ever and even more intense. Peter Schjeldahl, in the New Yorker, said that Dumas’ pictures are loaded with such weight that it’s a mystery how they don’t fall from the wall and break the floor.

Leather Boots, 2000.

A farm in Africa

Like Karen Blixen, Marlene Dumas also had a farm in Africa. Of Boer descent, her roots were forged by the essence of rural Afrikaaners: a solid, conservative milieu, strong religious principles but also openness and tolerance. Her childhood in Kuilsrivier (a Cape Town suburb) was a quiet, happy one, with a close-knit extended family of three grandparents and her Dutch mother, a woman wholly devoted to flowers, her three children and her vineyard. Marlene drew in the sand and learned from illustrated books and bibles. She enjoyed open-air cinema on Saturday afternoons. She had two brothers, one a viticulturist and the other a theologian from whom she learnt what it is to have a certain moral maturity and, more importantly, what it means to have a vocation. They were a close family, appearing not to need anything from outside their insular world. In 1976 she won a scholarship to study in Amsterdam where she still lives today: "My homeland is South Africa, my maternal language is Africaans, my surname is French .. I sometimes think I’m not a true artist because my heart is too divided up. My studio is my house. I think I’m like a snail, always carrying its life and homeland on its back.

The Blindfolded Man, 2007.

Marlene Dumas’ studio has no natural light. It’s small, white-walled, cement-floored, spattered by decades of work and paint. Almost everything is on the ground, photographs, brushes on paint pot lids and a small wooden brick she only very occasionally steps on to observe the results of her work. Now 62, Dumas often paints on the floor, on all fours, on a stretch of paper much larger than she is. She paints very fast, spasmodically, like an image captured in an instant on her retina, like water coming into contact with a black paint stain. From here emerge the fine black brush strokes that trace the eyes of a young nude. The water and the paint move around the paper leaving an abstract marking somewhat reminiscent of Bacon, of rivers or of a face reflected in the water at the bottom of a well.

"I’d love my paintings to be like poems. Verse is like naked words that have undressed themselves.” she says. Everything to do with Marlene Dumas aquires a literary density. She writes with her paint and she writes without making books, essays and poetry redundant. She also sometimes writes short phrases in some of her pictures. She likes to write her own exhibit material and press releases as she doesn’t see why or how anyone else should or could define what her art is trying to say. She has always considered herself a descendant of Alexandre Dumas and, for that reason, a “musketeer”, a warrior armed with both pen and paintbrush, too.

The Widow, 2013.

It is also Dumas behind the suggestive titles of her series or exhibiitions: The Eyes of The Night Creatures, Measuring Your Own Grave or her latest, The Image as Burden, yet one more example of the sheer quantity of layers, meanings and nuances in everything Dumas does. This last title comes from one of her small oil paintings of the same name. In it a man, posed Pieta fashion, holds a woman, the image, lifeless, in his arms. He looks at her tenderly and supports the weight of her body with no small effort. Dumas explains that the origin of that pose was a scene from George Cukor’s film, Camille, in which Robert Taylor carries Greta Garbo’s white-clothed body. Dumas’ scene emerges from a black background, two outlined profiles, almost African mask-like, are painted in Dumas’ smudged, discoloured tones, as if with dirty brushes: from black and deep blue to white. Black paint in an old kitchen tin thrown onto the floor of her studio is, perhaps, what Apartheid meant for Dumas.

The Image as Burden, 1993.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Marlene Dumas at the Beyeler Foundation - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

"Literature is writing from the heart, not the head." Great literature is written from the edge. So V.S Naipaul’s father advised his son, recently arrived at Oxford and before he became who he is today, one of the world’s greatest writers and Nobel Prize for Literature 2001.

Doris Salcedo (Bogotá, Colombia -1958) does exactly this; She sculpts from her heart, her innerness, herself. She is a narrator of pain, the pain of people broken by the unexplained absence of a loved one, by the crude outlines of wounds left by the bodies of those who are no longer here.

This sculptor, or “maker of objects” as she prefers to call herself, lives alongside the unfettered displaycase of terror that exists in Colombia, alongside the political drama and images in the face of which official history remains silent. It’s a not entirely uneasy juxtaposition. Photographs of bodies mutilated by chainsaws, sordid kidnaps and planned “disapperances”. In Colombia there are so many, far too many empty coffins.

What Salcedo does is travel to conflict zones, settle there for weeks or months, however long it takes, sometimes years, alongside the families suffering the loss of their loved ones, of any loved one, a daughter searching for her mother, a mother searching for her little girl.

She never tapes their testimony. She listens, she lets them pace out their emotions, she registers the frequency of fear, peers into the void along with them, slowly sketches the nightmare in their minds, joins in their searches for bodies, knows the textured panic and far-off gaze of a mother beside a mass grave whose child may (or may not be) buried there. Salcedo, however, eludes literal violence, not being interested in revisiting either the tragedy or the concrete facts. She prefers to be a hearsay/hearsee witness. She stores and catalogues these experiences, unassimilated, and inhabits them for a time, aligned with poetry and philosophy, until, from the most artistic hemisphere of her brain, the agony of those left behind can be made tangible.

Her initial original discourse, that spoke of the tension between life and death, has now turned towards the spectral world in which are circumscribed the lives of those undergoing tragedy and those who are forever separated form their loved ones, towards that other world through which relatives of the disappeared wander. For this reason, her sculptures have become more metaphorical, almost abstract, because what starts off from a poetic discourse then opens out as an inroad into the depths of our feelings, whilst forcing the spectator towards intuition, doubt and also the search for answers in her art.

"I don’t believe an image in and of itself, reproduced, dispersed, can stop violence. I don’t think art has that ability. Art doesn’t rescue. I don’t believe aesthetic redemption exists, unfortunately. I think that, as regards art, one cannot talk of any impact, let alone social impact, and least of all political impact; and only a very weak, minimal impact on aesthetics. (...) What art CAN do is create an emotional connection that communicates the victim’s experience. It’s as if the victim’s destroyed life, cut short at the time of the murder, might or could in some way continue within the spectator’s experience."

(Public Reason, Art, Memory and Violence, March 2013)

The Widowed House (1992-1994) Installation. Wood, cement, steel.

"ART CAN’T RESCUE."

Doris Salcedo has lived with women and observed their daily ritual of setting the table and dishing up dinner for a relative, a husband, a father who will never return. A daily rite they perform in the patient hope that the ghostworld of the disappeared will one day return their unburied ones to them.

It is for this reason that she takes the memories of the victims, their voices and their tears into such dear and close account. She turns to everday objects like shoes, tables, wardrobes or chairs, now emptied of their occupants, discorporate, vacated, and through these symbols creates the picturification of absence. As in The Widowed House (1992 – 94), she dismantles the normal what-we-know meaning of furniture. She draws us into another dimension, that of sorrow, mourning, that of a time of waiting in a cold place where tables are no longer the focal point of a family kitchen but are traversed by cupboards that have absorbed cement; where a sheet is made of rose petals; a town square adorned with candles at dusk; a building whose outside walls weep chairs.

Where burial grounds are table tops giving life to life. Where a 167 metre long faultline of jagged frissure fingers its way along the floor of a room in the heart of the art world, of the first world, of capitalism. Where doorframes recall the men who were dragged through them from their homes before being killed at dawn.

The brutality of the 1980s is one of the hardest in Colombia’s recent history, with hundreds of unidentified and unsolved, unnamed crimes. In 1990 Salcedo exhibited the installation piece entitled Untitled/Shows of Sorrow. Neat mounds of perfectly pressed and folded white shirts, each one filled with plaster and every pile pierced through by a pointed metal rod. By their side, six bedsteads, two of them upright, angled against the wall and draped with dried animal entrails. This commemorates the banana plantation labourers killed by paramilitaries, dragged from their beds while they slept: some were shot in front of their families inside the home and some outside. Their wives, eyewitnesses to the massacre, in a patient and painstaking show of sorrow, still launder and starch their husbands’ white cotton shirts, conscientiously ironing and stacking them away, for the day, one day, their husbands return to wear them, in their coffins.

The cold plaster represents the tomb, the laundry protocol yet another unbodied space.

It is in this piece that the secondary witness begins to take centre stage: she who remained behind, the woman who saw her husband being killed and lived on: the witness who survived.

"Violence creates images, continuously and continually. The paramilitaries left us with terrible images. Violence furnishs those unconscionable images of violence. I think one function of art is to counteract that imagery. And in doing so, to balance out the brutality surrounding us in this country.

"To give you an idea, Guernica was bombed, as were many other towns: however, the only one we remember is Guernica, because a pictoral record exists which humanizes the outright inhumanity of the bombing mission.

An image can do that, not by narrating exactly what happened, or giving consolation to the victim or aiding or easing their grief. No, never that, but it does dignify all of us as human beings. And that is a fitting memorial.”

“Untitled” / Shows of Sorrow (1989-1990). Both photographs. Installation. Cotton shirts, plaster and steel.

Doris Salcedo is a woman of robust physical appearance full of contrasts. Her pale complexion frames dark eyes absorbed in the effort required for long hours of work, the heavy burden of drama, the most tragic of testimonies. Her greying hair dwarfs an oval face that, at times, though rarely, is lit up by a wide and generously long smile. But her whole physical self seems designed to match her voice, a captivating voice, very engaging, very musical, with a beautiful Colombian accent and a gentle tempo. She often closes her eyes and settles into a silence that would enthrall whoever’s listening, until she finds the exact term, the right word or the most poetic turn of phrase.

It is vital to her that in every utterance she tries to communicate from the very depths of her soul. Sometimes, in this closing of her eyes, one gets an inkling of the pain her soul feels and the murmur of harrowing testimonies.

When she introduces herself, she likes to say that she has the wrong passport. She’s a woman, born in the third world, she speaks Colombian Spanish, she knows what it is to feel excluded, marginalised, she has experienced racism although not directly. She believes, also, that the rest of the world only sees her homeland as a brutal country that produces little more than violence and narco trafficking.

Readers will be aware that Colombia is a fine country, a country to be admired. Run through, admittedly, by the steel rod of Doris Salcedo’s sculpture. A growing number of Colombians and Europeans, mainly Spaniards, hope that the open negotiations between Colombian Institutions and FARC reach their peace-keeping goals. For this reaosn Doris Salcedo is able to transform those wrong roots y convert them into something positive. She says that being Colombian comes with huge experiential baggage but that, oddly, also makes her free. There are no large museums in Colombia, nor are there any art collections. Knowledge of the history of art comes only from books, which results in it being more theoretical, more wordy, more vague.

Salcedo has only ever worked in Colombia. Her 25 years in a studio would only be conceivable in her birthplace. But she makes the most of her every trip, every contact with beauty and the museums of the world. From Rome she once explained: “On Sunday, after a whole day in the MAXXI, setting up my exhibition, I felt tired and worried. I thought I needed to see Caravaggio before the day’s end. So I walked to Santa María del Popolo church where there are two of his masterpieces: The Conversion of St Paul On The Road To Damascus and The Crucifiction of St Peter. Mozart’s Requiem was playing in the background. What could be more perfect? At the moment I’m working on a new piece to present at the White Cube Gallery in London next May. Without Bernini’s Ecstasy of St Teresa, it wouldn’t have been possible to do that.”

Doris Salcedo outside the Palace of Justice in Bogota.

It’s 2015 and this is Doris Salcedo’s year. On 21 February the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago inaugurated a retrospective of her work.

On 26 June the exhibition moved to the Guggenheim in New York and from 6 May 2016 it will be at the Pérez Art Museum in Miami. Few Latin American artists have had such recognition. Salcedo, also, was the eighth artist to exhibit in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern and, after Juan Muñoz, only the second Spanish-speaking artist selected to do so.

In 2010 she was awarded the Velázquez Visual Arts prize. Over the last decade, her work has been exhibited in the MoMA New York, the Pompidou Centre Paris, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Reina Sofía Arts Centre Madrid and at the XXIV Biennial in Sao Paulo, Documenta 11 in Kassel and the VIII International Biennial in Istambul.

In the words of Carlos Basualdo, one of seven curators at Documenta 11, Salcedo’s work is key in that it represents a series of useful interventions for the history of contemporary sculpture. "Her oeuvre covering particular events is both of the moment and universal despite its obvious connection to events in Colombia.”

NEW YORK AWAKENED HER INTEREST IN SCULPTURE’S POLITICAL DIMENSION

Doris Salcedo first studied painting and, for a short time, was attracted to the theatre before devoting herself entirely to sculpture in the 80s.

In 1984 she completed a Fine Arts Master at New York University where she discovered the work of Joseph Beuys: "His work revealed to me the concept of social sculpture, the possibility of shaping society through art." Studying Beuys’ work, and her own experience being a foreigner in the city, awakened her interest in sculpture’s political dimension. On graduating, she returned to Bogotá to teach sculpture and art theory at the National University of Colombia.

"TIME IS THE ESSENTIAL ELEMENT OF THIS WORK"

Shortly after returning to Colombia in 1985, the Palace of Justice was stormed by M19 guerrillas. On the morning of 6 November, she was working only a few feet from where the massacre happened, a massacre which changed the message that Doris Salcedo wanted to get across about Colombian reality. In 2002 she put on an installation at the Palace of Justice which comprised the gradual and meticulously staggered hanging of 280 chairs from its walls. This lasted 53 hours, the same duration as the seige and its start coinciding with the exact time the first victim was killed.

A collaborator on the day says this about how the installation happened: "The limits of violence seemed to be lost at that time in Colombia. The idea was to follow the timescale of the seige. We started at 11.35am because that was the time they killed the first person. We had various objects being lowered down the facade at different intervals and rhythms. Synchronisation was very important. And time was the essential element for this piece that would last just 53 hours, the same duration as the seige. The running order was between 300 and 400 pages long. Each sheet set out how and for how long each specific pattern was to be achieved. That day we did a performance under Doris’s direction. She was outside, down on the street, directing us from below and we were upstairs, making it all work. Everything was labelled and there was a numerical order we had to follow, like with a musical score you read and play. I was a young boy when it happened in 1985. My memory is very hazy but, through this piece, it became part of my biography or of my biographical memory.”

"ONLY POETIC LANGUAGE CAN ENTER THE ENVIRONS OF EVIL"

The titles of Doris Salcedo’s work could arguably be classed as poetic. Skin Deep, The Widowed House, The Orphan’s Tunic, Silent Prayer, similar versions of which can be found in the poetry of Paul Celan. Salcedo evokes his poems and quotes them often, for instance Shibboleth and In Eins. Paul Celan, a Romanian of Jewish descent born in 1920, was one of the great post-war poets. When the Second World War broke out, he returned to Romania where he was sentenced to hard labour while his parents died in a concentration camp. His verse conjures up extermination.

"Celan believed that only the language of poetry could help us to enter into the environs of evil, into the vicinity of absolute injustice (...). Because only by means of intuition and metaphor, only through the intensity of a lyrical image, could we ever hope to understand a crime.”

These words by Fernando García de Cortázar describe the link between Celan and Salcedo, between the evidence of Auschwitz and Colombian crime. From 1965 on, Celan was admitted time after time to a psychiatric hospital where he wrote in Hebrew and, ultimately, in 1970, took his own life by leaping into the Seine.

Shibboleth (2007-2008) Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London.

Shibboleth (2007-2008) is perhaps the most universal and devastating of Salcedo’s output, part of the Tate Modern’s cycle of projects wherein artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Anish Kapoor or Olafur Eliasson were commissioned to exhibit their work in the Turbine Hall. Shibboleth is a project on a monumental scale. It is a linear crack 167 meters long and 70 centimeters deep that rips across the floor of the Turbine Hall.

The monumental nature of the work as regards its interaction with architecture is there to see. A collaborator explains: "There was a tiny crack in the floor at the Tate which Doris noticed on her first visit and decided to make this the source of this piece. Every centimeter was hand drawn by Doris. We researched cracks. We examined the edges, the inside walls above ground, in cement, on buildings. We looked like a crazy gang in the street staring at cracks in walls and floors. The next step was to figure out how to construct a readymade crack and export that to London. We decided on a metal structure, similar to how a brick is made but in the shape of a rock. We moulded the steel following the exact shape of the stone, then poured in the cement. The final result was the cast, with steel mesh embedded in it and its opposite twin.

We made 320 meters worth of cement because we had to do both faces of the crack. Everything turned out almost exactly as we’d planned but the image, the result, is something you can’t even begin to imagine until you see it.”

With this piece, Salcedo wanted to create a metaphor using biblical legend to highlight the exclusions faced by those of the third world as opposed to those of the first.

"I come from Colombia, a country full of the ruins that are the legacy of wars, imperialism and colonialism. That dictated my perspective. I am a third world artist. It is from that perspective, from the victim’s perspective, from the perspective of defeated nations, that I look at the world. For this reason my work doesn’t represent “something”. It is simply an insinuation of something. It is about trying to bring into being something that is no longer here. In this sense it’s subtle.”

PRONUNCIATION, A MEANS TO DISCRIMINATE

Shibboleth is the Hebrew word for "ear of corn" and plays a crucial part in a story from the Book Of Judges . Chapter 12 tells the story of two warring Hebrew tribes which culminates in the genocide of 42,000 members of the Efraim tribe after crossing the river Jordan in search of salvation. The Efraimites were distinguishable to their enemies by their inability to pronounce the “sh” sound and gave themselves away by mispronouncing this staple of their diet as Sibboleth with an “s”. So the word serves as a metaphor for the exclusion of an outgroup by ingroup speakers of any one particular language. And furthermore for segregation and borders.

“IT’S NOT THAT BIG A DEAL. IT’S JUST A SPACE. IT’S NOT LIKE BEING IN ST SOPHIA CATHEDRAL”

"When I went to see the space before thinking about the piece, what struck me was the attitude of the people there. Everyone was looking up and feeling that it was an astonishing size. I just thought: “It’s not that big a deal. It’s just a modernist, industrial space. It’s not like being in St Sophia cathedral or dwarfed by the pyramids in Egypt.”

But people seemed to be under that impression which I thought was incredibly narcissistic. What I wanted to do was turn this perspective on its head so instead of looking up, I’d force them to look down ... I wanted to inscribe something chaotic on this modernist and rationalist building, something that made the space negative. Because I think there’s a bottomless gulf that divides the human from the inhuman, the whites from the non-whites. I wanted to highlightthis rift which I thought was best observed in the history of modernity. When one reads about Modern History, one would think it was a uniquely European event. And the idea of colonialism, as well as imperialism, is marginalised, to say the least. I wanted this racism narrative to take centre stage because I think racism is the untold dark chapter of Modern History. So I wanted this crack to split the building in two and rip through it almost like a non-white immigrant barging into the monotony and consensus of white society.”

With this fissure, Salcedo means to take us to the centre of the rupture of all things ordered, the whole gamut of fragmentations: social, racial, aesthetic, sexual, geopolitical, cultural. It’s the antithesis in meaning of those walls constructed in recent history all over the world: the Berlin Wall, the concrete ‘barriers’ annexing the occupied Gazza Strip and West Bank ... With regard to its artistic significance, the Shibboleth crack means “too many things”, as Borges remarked, when he referred to it as an archetype that has accompanied humanity for millennia.

And now would be a good time to return to the poet Celan. There are too many words resonating deep inside us on a barely-there faint Hebrew line between Shibboleth and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem: the exodus, extermination, the final solution, the image of the cattle trains supplying Jews to the concentration camps, torture, cold, the prisoners’ emaciated bodies, Buchenwald, Dachau ... The 27 January 2015 marked the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

The Israeli architect Moshe Safdie rose to the challenge of designing a new Holocaust History Museum in Jerusalem which was inaugurated in 2005 and was awarded the Prince of Asturias Concord prize in 2007. Arrow-shaped, Yad Vashem pierces the hill of memory as would a splinter in our thumb: it doesn’t budge, a tiny little black dot, encouraging us to extract it from under our skin with tweezers. But no tweezers exist that can easily remove Yad Vashem once seen and in our head. Its design, like a cement ship in the form of a prism that juts into the mountain only to jut out as a huge skylight onto the Isreali sky, constitutes one of the most awe-inspiring impressions a museum can offer. The feeling of oppression under the triangular roof, the gentle slope downwards of the floor and then its gentle rise upwards, towards the exit, towards the light, the absence of windows, the choice to only use bare reinforced concrete, grey and cold, throughout the museum, create a sensation of claustrophobia and oppression similar to what one would feel in the underground passageways of a mine.

Thesame as the Turbine Hall in London, the cement floor of the museum is broken up, as if by an earthquake. In Yad Vashem, these gaps are actually glass display cases one can look down into, much as Salcedo forces us to do with hers in London, if we’re looking for answers. In Jerusalem, the shiver that runs through our body only chills more on discovering that those glass covers are really cases full of hundreds of children’s shoes from the Nazi Holocaust. A “Defiances” (Atrabiliarios 1992) that predates Salcedo’s but still talks of the same universal torture, only this time somewhat closer to the Mediterranean Sea.

Yad Vashem, Holocaust History Museum, Jerusalem

For “Defiances” (Atrabiliarios) 1992, exhibited in the White Cube gallery in London, Salcedo spent nearly three years listening to relatives of the disappeared: that cruel politically motivated phenomenon of forced disappearance and the hole left by the victims’ belongings. She studied the way in which families related to these objects, now souvenirs, hoping their owners will return for them, unable to let them go.

Relatives donated shoes the victims had once worn, and these were Salcedo’s catalyst for “Defiances”. Her intuition inspired her to bore twenty little alcoves into the wall and place the shoes inside. “Colombia is the country of unburied death, of the unmarked grave.” So a pair of white shoes, that might be a bride’s from her wedding day or a Sunday afternoon tea-dance, are displayed in a tailormade tomb, shrine-like, and partially obscured from our view by a thin membrane of animal skin roughly sutured to the wall with black surgical thread. Wound, fissure, burial, exposure ...

As Salcedo explained at Harvard, “When the specator gives the work a moment of silent contemplation, in that moment and only in that moment, is when the emotional connection happens ... Art has enormous power: the power to take back control of life, of humanity, of life that has been profaned.”

“Defiances” Atrabiliarios (1992) Installation. Shoes, animal skin

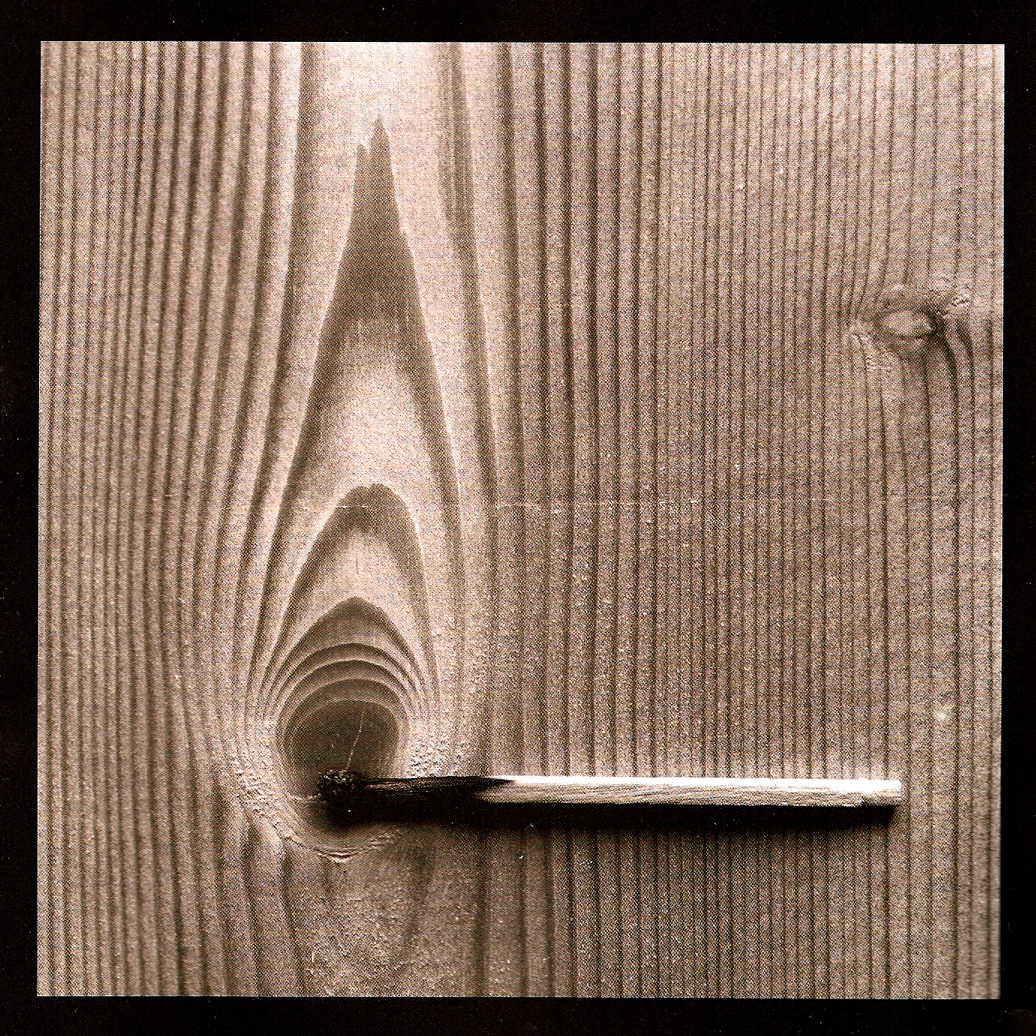

In 1997, and within the Unland series, came The Orpan’s Tunic. Behind this work is the story of a six year old girl. Every time Salcedo went to visit her, the little girl was wearing the exact same dress. Some time later she learnt that this was the dress her mother had handstitched for her and the one she was wearing the day her mother and father were killed in front of her. Here, the public think they are seeing an everyday object. A table. However, it soon becomes apparent that it is in fact two different tables, joined, with the smaller brown half slotting under the wider white one. Up close, one can see the tiny holes through which human hair has been painstakingly threaded, ending in a border where the hairs are directly threaded into the wood. Salcedo’s work is always meticulous, time-consuming, highly detailed. ”Of course it’s insane, it’s absurd – comments an assistant to Salcedo – And it’s an enormous waste of time and energy. A team of 15 people worked on these pieces every day for 3 years. It reminded me of Paul Celan when he said: “It is only the absurd that shows the presence of what is human.” But here too it had a connection with the squandering of lives. “It was the peak period of paramilitary massacres in Colombia. It was my way of showing how life could be wasted. But at the same time, how something poetic could come out of it, some proof of our human presence, of the victims’ humanity, of the fragility of life and the brutality of power. I think everything was here in this gesture, sewing hair through wood.”

Unland. The Orphan’s Tunic (1997) Wood, human hair, silk.

Skin Deep (2012-2014) is a huge swathe of material in shades of ochre and red, its soft folds falling on the floor of the White Cube gallery, flooding it almost, like a soft-waved sea. That’s all. Except silence. As always happens with Salcedo’s work, after the initial impact, after the query and the doubt, we see that the fabric is made up of millions of rose petals, sewn and knotted together one by one with surgical thread. An efemeral work, it will ultimately perish as a rose will. A video explains the arduous process involved for those petals, the chemical process of immersion in a glycerine and collagen solution to give them the malleability and durability necessary for them to be stitched, one by one, into pieces that would then be ironed in gigantic, custom-made presses. Despite all this, the fragility of the material is total. Salcedo explains how this fragility, which almost makes it untouchable, which requires one to breathe more softly near it, all this is intimately related to its meaning. In order to dignify a person, it’s vital to return to beauty. Transforming pain into beauty is, however, quite perverse.

Frequently in Colombia, the body becomes a battleground. Skin Deep is the hommage Salcedo pays to the body of a woman, a nurse by profession, tortured, killed and finally cut into pieces. The offering of millions of petals sewn together, the delicacy, the wound, the life of a nurse stitching up wounds with a needle, a rosy complexion, the surgical thread, the tweezers, the pain, the bruised skin, the superimposed petals, the flesh, the rose, the vulnerability, death. The skin, a mutilated, disjointed body being put back together is something we don’t look at, we show respect. It is one woman’s subtle tribute to another, in women’s language. To hear Salcedo talk of this work is to hear her voice soften and slow, to see her eyes close on the horror and sorrow, til she finds the most respectful words: “ In the same way that we don’t look at a wound.”

In July 2014, Salcedo received the Hiroshima prize, an acknowledgement awarded every three years in remembrance of the victims of the first atomic bomb. This prize honours those artists whose work is in pursuit of “the search for permanent peace”.

“What is dying in an attempt to cross the border? The word that defines my work is impotence. I am completely impotent. I feel I’m responsible for everything that happens and I always get wherever it is too late. I can’t give anybody back their father or son. I can’t solve any problems. I can’t do anything. It’s a lack of power. But as someone who lacks power, I stand up to those who have it and use it to manipulate lives.”

- Doris Salcedo: Art as a Scar - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

Olafur Eliasson (Copenhagen, 1967), who this year was on the verge of winning the Princess of Asturias Award for arts in a tight battle with the winner, the cinema producer Francis Ford Coppola, is one of the most outstanding of the multidisciplinary and experimental artists of present times. He has exhibited at the best contemporary art museums of the world, such as the Tate Modern in London (2003) the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid (2003) and the Modern Museum of Art (MoMa) of New York (2008).

Olafur Eliasson, a visual artist known for his experimental installations, sculpture, photography and cinema, is a creator who finds inspiration in certain motifs and ideas of the recent German philosophy, ideas he tries to put into practice in his work. Following this inspiration, his purpose is therefore not limited to creating works of art and experimenting along the already consolidated habitual modes. He wants much more. He aspires to educate the spectator to open to new forms of perception and understanding of the world through his participation and inclusion in the work of art. He stimulates his perceptions and sensations to see reality from other prisms and to have new experience and knowledge of his own subjectiveness.

A work of art is only complete when there is interaction between it and the spectator, when the spectator brings in their experience and interpretation to also become the creator of the work. This reception aesthetic is therefore already far removed from the concept of work of art as ”work in itself,” in other words in that in which there would only be a place for a single concept and a single suitable interpretation, that of the meaning given by the author. Eliasson’s work, on the other hand, is fed by the plurality of meanings given by the spectator.

What Eliasson suggests is a transformation of the way we observe reality, a becoming aware of our prejudices and conditioners to open to another way of relating to it. If we do not dismantle our world as we perceive it and understand through our interaction with it through our space-time configuration, by projecting our concepts, emotions and sensations on it, we will never be able to open to experiencing other worlds.

One example of it would be his splendid The Weather Project (2013): an immense nightfall is reproduced in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London, and which is designed so that visitors might experience not only the importance of the weather in our survival since time immemorial and in the formation of our social structures, but also the relationship between existential time and our limitations as finite subjects.

Here artist and work blend at the time when the observer interacts with the work and enters it to create a common “now” between artist and spectator. Experiencing the “now” for visitors is therefore the result or remembering the past (the artist’s conception, their own past experiences) and of anticipating the future (the meanings and projections suggested to them), thus becoming the “now” on the crossroads of both time dimensions.

In 1995, this artist created the Olafur Eliasson Studio in Berlin, in which around 90 people between architects, engineers, graphic designers and historians of art experiment, investigate and produce works developed with elements such as light, water, colour, space... However, the fundamental figure of this creative group in recent years was the recently deceased engineer and mathematician Einar Thorsteinn. Olafur attempts to synthesise art and science as the great artists of the Renaissance did.

The characteristic thing about this artist is therefore that he understands the world from the Kantian perspective of the configuration of reality by the subject who projects his subjective setups to give a cultural meaning to the world. Therefore, with his art he tries to nurture another kind of view of the world with new perceptions and sensations.

Sometimes, through his visual games, an experience can be produced of pure sensations, in other words, one that is not reflexive and manages to bring spectators out of themselves to be measured in the work, or which can cause the active participation of the subject in it. Then the importance is seen of the spectator who interacts with the work with their multiple interpretations.

The installation of four waterfalls on the East River in Manhattan (New York Waterfalls) or using ephemeral green ecological pigments to dye the waters of Stockholm, Tokyo, Los Angeles or Norway, amongst others (Green river), reveals the will to exercise our senses towards other possibilities of perceiving and experiencing this other reality configured by the effects of our cultural intervention on it.

This artist’s proposal is to go beyond the traditional role of art in our culture, when we relate to it according to the subject-object setup. His aim is to enter an experience of the creation of culture through art, which is not just the work of a creator, an artist in this case, but also that of the receivers of these works that are not complete if they do not project meanings on the works to complete them with their interpretations. In this sense, the spectator forms part of the work, is inside it like these boats on the river’s green waters and the visitors entering the artistic dusk of The Weather Project.

- Olafur Eliasson - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art historian

|

|

Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. (Gen 1, 2-3)

CaixaForum Madrid is currently exhibiting 245 polaroids from the Genesis series by Sebastião Salgado (born in Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 1944) until May 4 — an exhibition which serves as a testimony to one of world’s most relevant contemporary photographers. He was awarded the prestigious Príncipe de Asturias de las Artes award in 1998 and during his career he has worked with some of the best photography agencies in the world, such as Sygma, Gamma and Magnum, before setting up his own, Amazonas Images. In this exhibition the photographer shows us the incredible, remote places he visited during his 32 expeditions lasting eight years, just before he turned 70.

The first thing you notice in Salgado’s photography is his powerful aesthetic sense; and his message slowly, gradually seeps through from the images, slow and gradual as elephant’s footprints on the soil. What you see in his photos is an area occupying 46% of the planet, and which to this day is virgin land — the same as it was on the first day, according to Genesis.

We decided to carry out more in-depth research on the theories and biography of this artist, certain as we were that someone like Sebastião Salgado should have much to say about an area of life and of the heart that is only open to those with a certain view of the world. Rhythm, Coherence, Passion. And we suddenly realize that it’s his inner journey that we’re really interested in.

Salgado is a man of clear vision and slow speech; his spoken English has an attractive Brazilian Portuguese hint to it, and his slow speech is not due to linguistic hesitation, but is the sign of a man who has seen much of the world and, more importantly, a man who observes mindfully. You see this in his careful choice of answers, and in how well he expresses them.

Like all good photographers, he has made a pact with slowness. “I walk a lot, I do some of my reporting on foot because I use the time to look around and to feel life, to feel nature. Slowly. If we don’t do it slowly, we end up burning out. Most often, the essence lies in the curves, in the twists and turns of the journey, not in the straight lines.” He compares photographers to hunters because they both live in waiting, fully immersed in their own authentic processes. “We must experience the pleasure of waiting.”

Before the Genesis project, Salgado had focused on photographing people, who he sees in a very different light, broader, more real: a vision we’d like to share with him. “I have learned that, at times, where there is life, there is also death. In Kazakhstan, the same phosphate used in agricultural fertilizer is also used as napalm, an effective combat weapon. In Bangladesh, the same fabric components found in jute are used both for the production of sacks for cereals as well as for the sand-filled sacks used to build trenches in wars. When the jute sack is attacked by bullets, it closes itself thereby keeping the sand inside and protecting the soldiers.”

Listening to his life story, we realized that Salgado is one of those people whose vision of the world and of people we’d like our own children to have. By the time they reach the age when they’re overcome by a powerful natural curiosity about the world and they look for answers in stories and pictures, it would be wonderful to sit them down on the ground, and let them look up and listen to a wise man in front of them, whose eyes, the eyes of a hunter of slow images, are filled with real, genuine stories: “When I was in Ethiopia I travelled 850 km on foot. I discovered that that was the origin of all the fertile land from the banks of the Nile. I travelled to a Christian community, where Egypt’s first jews settled. It was just like landing in the middle of the Old Testament. Rather than being a journey of 850 km, I see it as a journey of 6,000 years inside myself.”

De Mi Tierra a la Tierra (From My Land to the Earth) (La Fábrica) is the title of his memoir, in which he talks about how the Genesis project begins in the Galapagos Islands, following in the footsteps of Darwin and taking the The Voyage of the Beagle as its guide. This is where Salgado learned that man is not the first species gifted with reason. He also describes certain unexpected situations he discovered in the natural world, for example that when the time comes for the common gannet to mate, it’s the female that chooses the male. The males introduce themselves before her, they dance, open their wings and show off their body. When the female makes her decision as to which male to mate, they fly off together for about 15 minutes. One by one, all the females follow this ritual of allowing the males to court them and then choosing one. For the duration of that season, this will be the female’s only mate and the father of its babies.

BLACK-BROWED ALBATROSS IN THE ARCHIPELAGO OF THE WILLIS ISLAND, SOUTH GEORGIA, 2009.

Although the Hebrew name of the first book of the Bible comes from its first word, Beresit (meaning “in the beginning”), its Greek name is Genesis, in reference to the “origin” of the world and of man. Salgado is a non-believer, yet his purpose with the Genesis project is to show “the dignity, the beauty of life in all its aspects. And of course the fact that we all share the same origin.” He told us about the time spent on the Galapagos Islands, about how he once noticed the front legs of an iguana and how his imagination led him to see in them the hand of a Medieval warrior, clad in chain mail. The incident made him suddenly aware of the similarities between species, and led him to decide on the name of the project: Genesis.

Looking at this photo while we were passing through the halls in front of the Botanical Gardens, we all had the same doubt: Is that King Arthur’s hand? Or it could it be Ironman’s?!

SEA IGUANA, GALAPAGOS ISLANDS, ECUADOR, 2004

Salgado was born on a farm in the Brazilian mainland, where he learned to observe and to love the lights around him; he grew up under densely overcast skies and storms through which light would filter. He spent his childhood among large expanses of land, streams, rain seasons and long seasonal migrations among thousands of oxen.

At the age of 20 he fell in love with his other half, Lélia. They arrived in Paris together in 1970 — they were fleeing the political turmoil in Brazil at the time. During his first European summer and in a Two CV, they drove all the way to Geneva just to purchase some photographic material at a better price. Lélia had to photograph buildings for her classes at the Faculty of Architecture. Although neither of the two had any previous knowledge of photography, they both instantly fell in love with it. And that is how photography became his way of life. He discovered Africa while working as an economist at the World Coffee Organization — he became passionate about the continent and wanted photograph it constantly. He gradually left his day job and began to consider himself a full-time photographer.

As always together with Lélia, they began his other great project: O Instituto Terra. The Brazilian coast, right from its origin, has been covered by an atlantic jungle — around 3,500 km inland — and the land belonging to Salgado’s parents once belonged to this ecosystem. Once political amnesty was reached, the couple decided to return to their country, but on arriving they found themselves having to deal with the issue of deforestation: the well-known perobás (a variety of oak) and other species of trees had been cut down, the fertile lands once covered in pasture had been destroyed, and the flow of water had been let loose on the area with no barriers in place, causing inundations. “Lélia said to me one day, Sebastião, let’s replant the trees” and without any botanical knowledge nor economic means, and feeling very much like city-people in a natural area they didn’t even live in, they bravely decided to embark the adventure. After six months they were involved in the replanting of 2.5m trees of the varieties found in the original jungle, and in the creation of the first Brazilian National Park located in a completely destroyed piece of land. Since then and to this day, the land belonging to his parents has been protected. And with the trees came the animals, such that his beloved childhood became a paradise once more, almost more beautiful than the one he remembered. This spectacle of the recreation of the circle of life was what made Salgado decide to capture with his camera the natural beauty of those places on earth where man has not yet set foot. “Genesis is my love letter to nature.”

O INSTITUTO TERRA, MINAS GERAIS, BRAZIL, in 2001, when the replanting of the Brazilian atlantic jungle began, and in 2013 having reached their goal.

“Photography is my life, it’s my way of living with meaning."

During the making of Genesis, Salgado transitioned from analog to digital photography. Between 2004 and 2008 he used Pentax 6458 cameras and medium format, 4.5 x 6.

He uses monochrome with great dexterity, offering a whole new vision of black and white photography; the tonal variations of his work, the contrast between light and darkness, remind us of the Baroque period and of the works of the great masters of chiaroscuro, such as Rembrandt and Georges de La Tour.

In black and white we seek greater impact. When I was working in colour, the beauty of the blues and the reds seemed like they were erasing the emotion of what had been photographed. It diluted them. With black and white and all its range of greys, Salgado forces us to concentrate on the looks, the attitudes, and the density of the people: “When we see an image in black and white, it pierces us, we assimilate it and, subconsciously, we colour it.” For the photographer the moment of pressing down on the shutter release is unique and magical. Photography is the interpretation of a work in which various elements are linked together: people, the wind, the trees, light, the backgrounds… But in order to see the photography, the photographer must integrate completely with what is around him. It’s wonderful to read how Salgado describes those moments of bliss just before the shutter release: “You know you’re about to witness something unexpected. When you’re at one with the landscape, the moment, the image starts to construct itself in front of your eyes. In order to see it, though, you must be part of the process, and once you achieve this, all the elements start to work together with you… I love just sitting there for hours watching, framing, working deeply with light… You’ve got to love what you do.”

{youtube}nHJWgQxTous|600|450{/youtube}

To conclude, here’s an homage to two geniuses and their images.

Sebastião Salgado, Ciega a causa de las tormentas de arena (Blinded by the sandstorms), Mali, 1985. Pablo Picasso, Celestina.

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

"The nerve pathways are something fixed, finished, unchanged.

Everything may die, nothing rebirthed "

Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

Frank O. Gehry in front of a blank page. The terrifying moment of creation. Feeling afraid, waiting for inspiration, stalled by emptiness. Nights of uncertainty. Conceiving an idea: suffering and ecstasy.

We are our brains. The mind is the result of dialogue between each of our hundred billion neurons. How would the impulsive lines of ink appear, led by the right hemisphere of the brain, where Gehry began to dance on paper in one long, winding movement to illuminate what would be the profile of the Guggenheim museum Bilbao?

We think in the head of a genius.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, 1991-1997.

Let us return to the illumination. It is the time when the paper of an artist begins to fill with projectiles: papers flying above the tables with crumpled despair; rough reports of more or less tight balls, containing unfinished sentences, ideas that were lost on the path from the head to the hand; sketches and drawings that do not work.

When Frank Gehry is asked where his imagination comes up from, he rests his pen on the desk, looks up from his glasses, and lets suspense fly in his studio until that gaze drops. Gehry is well aware of his Jewish ancestry, always down to earth, to reality, and says: "Inspiration is in that bin. Look in there, think of the caves, spaces, textures containing that trash". Much of his reflection is there. Writers, painters throw their errors into a basket. Gehry shows his, he wrinkles pieces of paper and transforms them into towers and palaces for music, hospitals made of metal forms that seem to melt under the sun, office buildings embracing dance.

He converts his dream ladder for Vitrainto into the same spiral, the life on a paper. Nothing dies: from the smooth wrapper leaf there is the outcome of a final sketch, to the less valued, relegated to the bottom of a trash can.

Lou Ruvo Clinic, Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America, 2005-2010.

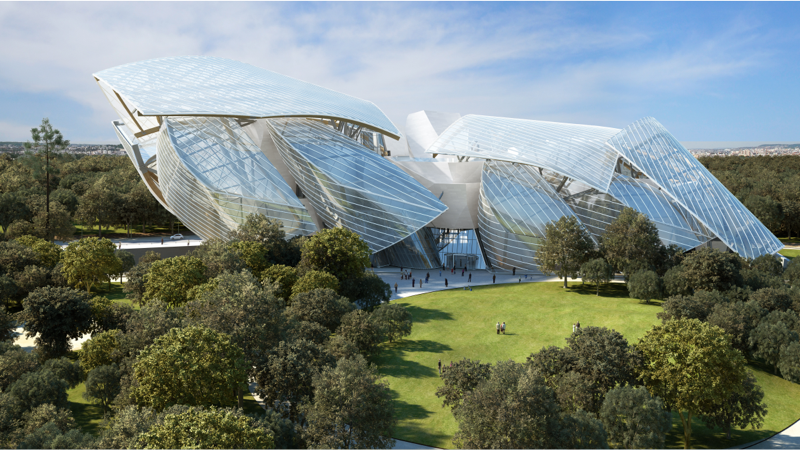

Frank Gehry (Toronto, 1929), winner of the 1989 Pritzker Prize, is probably the world's most wanted living architect. At 85 years old, he has become a total cultural protagonist. In Spain he has received the Prince of Asturias Award. In Paris, as well as the devoted retrospective to him by the Centre Pompidou, he inaugurated the new headquarters of the Louis Vuitton foundation and decorated the windows of their stores.

When in 1997 he completed the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao this architect-inventor-artist, who likes to say that many of the grooves are tribute to Don Quixote, found himself in a similar position to that of Miguel Ángel after his speech in San Pedro of the Vatican: revolutionist of contemporary architecture.

The strength of Gehry - described by the experts - lies in the motion that he embeds within the architecture, in his ability to create that movement from something inert. It is a contemporary cubism that serves to transform a line of twisted metal skin against the sky and glare of the sun, in a factory of feelings and infinite perplexity for its viewers.

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France, 2005-2014.