- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

A little over a month ago, on 20th April 2020, one of the greatest photographers of the last three decades died aged 92. Gilbert Garcin, whose artistic career began on his retirement from the job he had devoted his whole life to - a small lighting manufacturer in Marseille - was 65 years old when a whole other world opened up before him ... that of photography.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

A little over a month ago, on 20th April 2020, one of the greatest photographers of the last three decades died aged 92. Gilbert Garcin, whose artistic career began on his retirement from the job he had devoted his whole life to - a small lighting manufacturer in Marseille - was 65 years old when a whole other world opened up before him ... that of photography. What kickstarted his new lease of life was a course he enrolled on at the 1995 "Les Rencontres d'Arles" Festival and from then on, nothing would ever be the same again for this budding sexagenarian artist. The recently-opened Paris Photo Salon of 1998 afforded him the opportunity to get his work known internationally and take him, in a very short space of time, to the highest heights of success at photography.

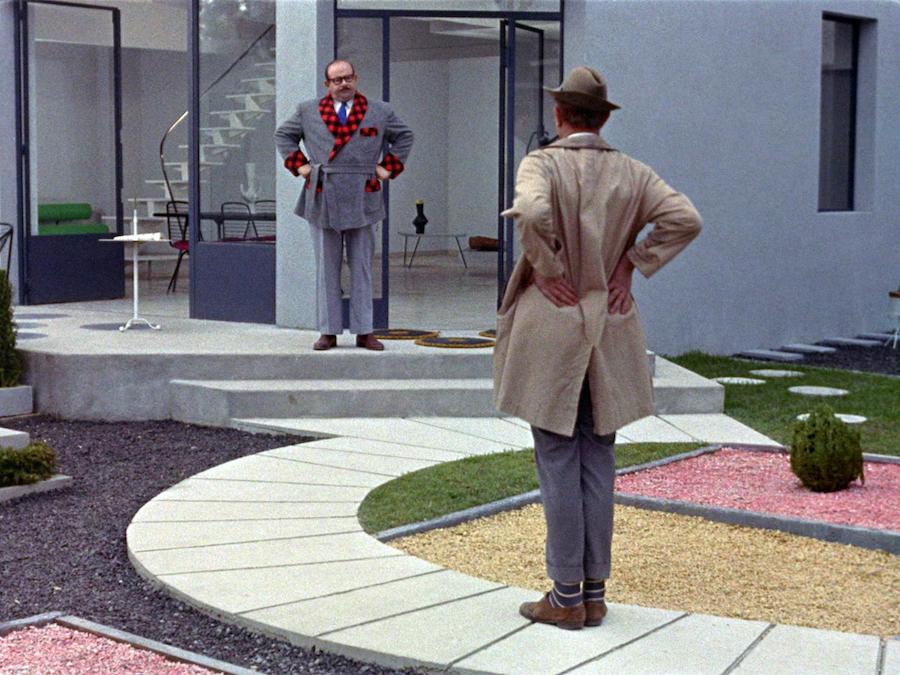

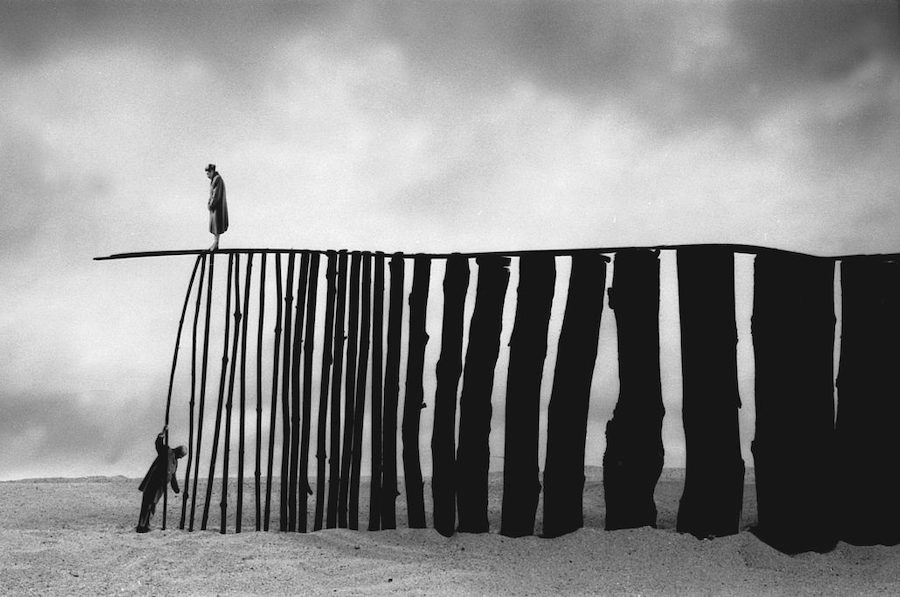

Through his images, we see a new world where simplicity and complexity walk hand in hand, creating new realities and turning the absurd into the commonplace. His way of looking at things transforms objects into something different, placing them 'through the looking glass'. It is perhaps this that linked him, by his own acknowledgement, to the filmmaker Jacques Tati and the Belgian painter René Magritte. Like them, Garcin shows us how to see a new world between the visible and the invisible, the real and the imagined, the borderline between the conscious and the unconscious. The photo montages, or staged photos as he called them, are the ideal means by which to create those mysterious images with elements of surprise that run throughout his work and manage to say the unsayable. He had great trouble choosing titles for his photos and he himself often found no explanation at all for his own creations. I am quite sure André Breton would have been fascinated by the compositions Garcin created and captured with his analog camera, optical inventions that never lose their naivety and humour, and where everything is false and real at the same time. His photos also have something of the metaphysical, those geometric representations that intertwine with the human figure in search of a change of relationship and meaning in order to build new associations.

Behind every snapshot creation is a craftsmanship that took between 20 and 30 hours of studio work. On the table of his modest workshop in Ciotat, Garcin would stage the different scenarios, sometimes skies borrowed from 19th-century painters, other times small sandy surfaces or linear compositions inspired by Paul Klee's drawings or even vintage film reels on which he would overlay his image, laid out on a stand. The viewer, on approaching any of his photos, will discover their play on scale, their imperfections and the naturalness and uniqueness that encapsulates each of them.

Garcin's work is so personal that he himself models for his own photos. It is he who functions as a working part of his creation, he is the actor playing the leading role and he who directs and calls the shots at will, according to circumstance. He has said: "It's not me, it might be my double, but essentially you have to see him as a character."

Perseverance

He made his first appearances wearing a hat that he soon abandoned in favour of an overcoat he had inherited from his father-in-law, a family heirloom which he kept as his hallmark until the end of his career. On occasion, he includes his wife as an indispensable complement to his storytelling.

It would seem that the only references to actually influence his work are found in films of the 1920s and 1930s. His grandfather, Auguste Garcin, ran a small cinema where, in the 1890s, the Lumiere Brothers films were screened and where he lost himself in the silent films of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin.

The deep sense of loneliness and atemporality that permeate his work make him an artist of great intuition, sensitivity and awareness of the unsettling world we have to live in, always leaving the interpretation up to each observer. Conveying without imposing.

An atypical artist and modern-day craftsman who created, with simplicity and an unbounded poeticism, a disjointed unity that made him a genius. And quite simply, moving.

Gilbert Garcin Photography

Organised by the photographer José Ferrero in the spring of 2017, the Niemeyer de Avilés Centre held the exhibition “The utopias of Gilbert Garcin” showcasing over 80 works by the French photographer.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Gilbert Garcin - Making the Meaningless Meaningful - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

On 7th March 1500, Emperor Charles V was baptized at St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, a fortnight after his birth. The verticality of the central nave, with its very subtly pointed arches shooting up into the sky, was draped in gold and silver-threaded Flemish tapestries; the Gothic stained glass windows, with their heavenly entourage, fulfilled the symbolic function of transforming the interior illumination into an other-worldly light distinct from that outside.

|

Colaborating author: Marina Valcárcel

|

|

On 7th March 1500, Emperor Charles V was baptized at St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, a fortnight after his birth. The verticality of the central nave, with its very subtly pointed arches shooting up into the sky, was draped in gold and silver-threaded Flemish tapestries; the Gothic stained glass windows, with their heavenly entourage, fulfilled the symbolic function of transforming the interior illumination into an other-worldly light distinct from that outside. A walkway with forty arches was built, each one representing the future states of the newborn and one of the godmothers, Margaret of York seated on a throne, carried the baby, preceded by a lavish royal entourage. This baptism was conducted in the manner of a coronation, leaving behind the simpler medieval ceremonies of the past and instituting this Burgundian ritual in the Spanish crown. But all the pomp and solemnity failed to prevent the eyes of those entering the cathedral being drawn towards the Vijd chapel. There, on 6 May 1432, The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb altarpiece, the Polyptych of Ghent, painted by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, had been inaugurated, offering its awestruck audience a surprisingly new way of viewing art.

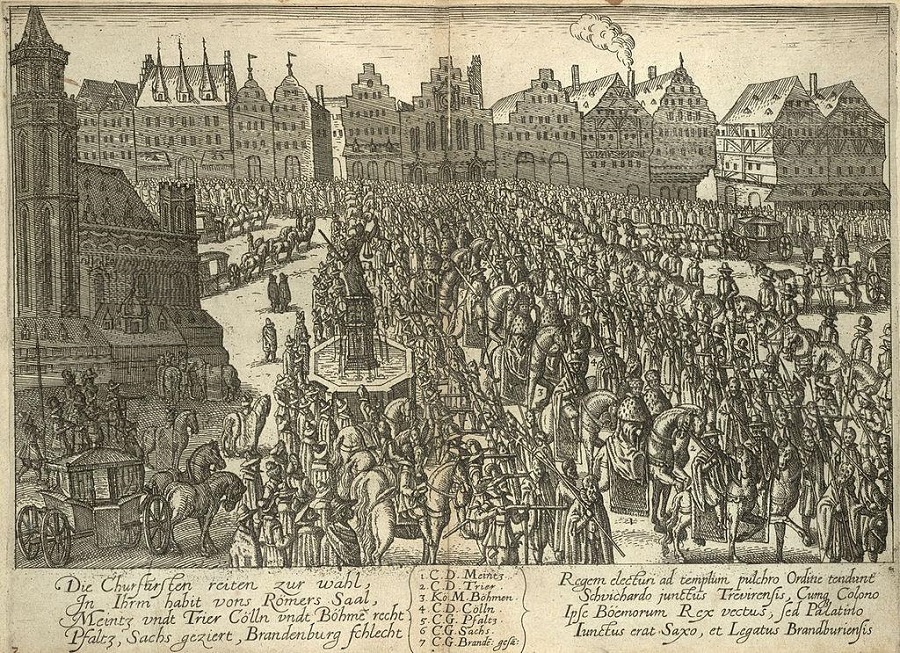

Ceremonial cortege, German engraving, 16th century.

In 2012, a team from the Royal Belgian Institute for Artistic Heritage began restoration of the Polyptych in a laboratory at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MKS). During the first phase, when lifting the different layers of varnish, large areas of overpainting were discovered that - probably since the 16th century - had kept van Eyck's work hidden. For the first time, it became possible to see the outer panels of the Polyptych in their original state: the colours of skies and cities, fabric folds and pins hidden in headdresses, light bathing the skin of its subjects and the illusory feel of simulated marble in the statues of the two Saint Johns. These were findings that allowed for us to intuit and piece together many of the mysteries surrounding the paintings of Jan Van Eyck (Maaseik? c. 1390 - Bruges, 1441). This was what sowed the seed of this unrepeatable exhibition displaying all of the eight panels before they return, forever, to the Cathedral of St. Bavo. They form the backbone of the thirteen mysterious, dark rooms of the exhibition, their walls alternately painted the red and ultramarine of the Virgin Mary's robes and their lighting that seems to emanate from inside the paintings: almost 100 works comprising Masaccio, Pisanello and Fra Angelico, his Italian contemporaries, some of his Flemish contemporaries and, above all ,13 of the 20 known Jan van Eyck paintings in the world, constituting a never-before seen collection.

Laboratory at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MKS). Restoration of the Polyptich

The traveler visiting Bruges will see the small enclosed gardens with their espalier fruit trees and the high pointed arrows of the bell towers emerge around the canals and will be seeing the same streets and their houses and the same churches on the other side of a bridge as Van Eyck. Little seems to have changed since 1430. Similarly, when we stand facing a 15th-century Flemish painting, we believe that we are infltrating the intimacy of life of another time.

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail). Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, Cathedral of St Bavon, Ghent.

Silks and Patrons

The birth of Flemish painting was occasioned by the French defeat at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 which spelt the collapse of France for decades. Far removed from the ongoing Anglo-French Hundred Years War, Flanders devotes itself to its vocation of commerce. The 1419 assassination of the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, convinces his son, Philip the Good, to sever ties with the Valois and move the capital of Dijon to that protected and free city of Bruges into which goods from the Mediterranean, the Baltic and all the luxury ships of the East flowed: spices and pearls, Turkish rugs, silk brocades from Syria ... objects that will inundate the spaces between Van Eyck's Virgin Marys, altars and donors. Bruges was already the well-established centre of a thriving school of illuminators, among whom and under the influence of the greatest sculptor of the time, Claus Sluter, Van Eyck begins to paint the folds of robes as voluminous as portico sculptures and saints' faces contorted by expressions of pain and to let his painting take on the preciosity and colors of the jewelled and enamelled cover of a Book Of Hours. The Duke of Burgundy's court was a paradise for fortunes such as those of the Italian banker Tommaso Portinari or that of Chancellor Nicolás Rolin, who favoured the arts and generated much patronage. In this environment, May 1425 saw Jan van Eyck's appointment as court painter to Philip the Good, for whom he undertakes numerous long and secret journeys of which only one destination is known: the Iberian Peninsula.

Limbourg Brothers: "May", calendar page from the "Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry" (1411-1416). Condé Museum, Chantilly, France

Subdjugating the light

So who was Jan van Eyck? What was his optical revolution in response to? What was it that made him paint that way?

One could say that, as a painter, he enslaved subjugated and conquered light, subduing and taming it until he was able to illuminate every corner of his paintings with it. To achieve this, he made use of the well-established tools of antiquity which he mastered and made his own. The most recent scientific analysis, after the restoration of the Polyptych, shows that van Eyck mastered all oil techniques and took them to their limits, reproducing every possible texture from silk to hair, from stained glass to Valencian tiled floors, crowns, the light from a child's skin or the matte tone of an old man's hand, books, bindings with their gold lettering, the sky and the pale brightness of the setting sun. Likewise, he portrayed a forest breeze, rays shining through the Gothic windows of a church and the whole reflection of a city on a stretch of lake in the background of a Saint Francis whose stigmata glowed with the precise amount of sheen in every drop of congealed blood.

Everything he saw in nature he conveyed with his brush: different types of rocks, variations of clouds and even depictions of skin diseases and no one, except Leonardo da Vinci, managed to paint the human eye with such precision, the eyelids, the veins and the steadiness of a fixed gaze.

Jan Van Eyck, Saint Francis receiving the stigmata (c.1440), Philadelphia Museum of Art

Erwin Panofsky demonstrated how, unlike his Florentine contemporaries, Van Eyck had no interest in applying the mathematical laws of perspective. In The Annunciation scene from the Ghent Altarpiece, the floor and ceiling beams not only do not converge, they do not even come close. In the Washington Annunciation, far from a single vanishing point inside the church depicted, there are several. Van Eyck found an empirical solution for the representation of a compelling space based on direct observation. With it, he came to create twofold perspectives, suggesting distances both panoramic with horizons as real as they are implausible and meticulously detailed - what Panofsky defined as the juxtaposition of his microscopic and telescopic gaze. And so, in the foreground are the interiors his characters inhabit, that intimacy that today fascinates us because we recognize in it our own world, the modern world of the individual and their things: gloves and carpets, musical instruments, lilies and easels and reading stands. That eagerness to portray everything, even what it is not necessary to show, is overwhelming. It is that same domestic and modern intimacy that will later be painted by the likes of Vermeer and De Hooch and Chardin, while in the background or somewhat higher up, another scene unfolds behind a window or on a balcony: a view of a Flemish city, its towers, belfries and streets lost in a horizon of lakes, blue mountains and tranquil skies. Landscapes both infinite and of pinpoint accuracy that in turn, centuries later, a young Ingres would paint in his 1806 "Portrait of Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière".

Jan van Eyck , Annunciation (detail)

Jan van Eyck, Annunciation (c.1430-35). National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Mademoiselle Rivière (c.1793-1807). Louvre Museum, Paris

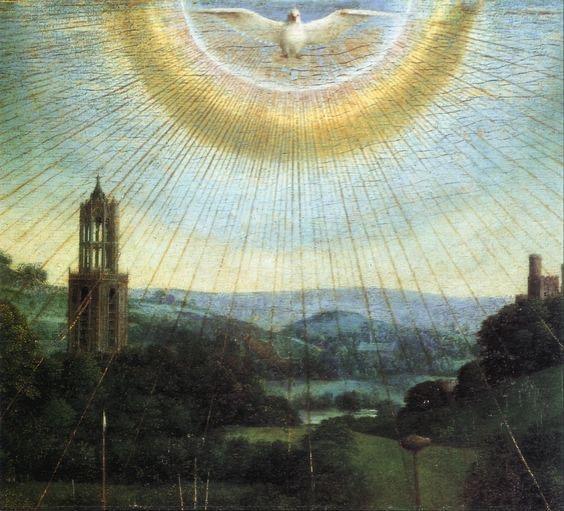

Van Eyck suffered from an obsessive fixation with the way light covers and forms images from reflection and refraction. The mirror must have permeated his world not only as an object, but also as a metaphor. Some of his knowledge came from observation, but in his time he was considered the first pictor doctus (illustrated painter) north of the Alps. He was familiar with classical authors, had read Pliny the Elder, was an expert in geometry, in archaeology, but above all, he knew optics, that Late Medieval science based on the discoveries of Arab mathematicians, such as Alhazen. Van Eyck used and perfected it in the development of an optical revolution that still impacts us emotionally today. The lighting of the Ghent Altarpiece corresponds to the natural incidence of light through the southern windows of the Vijd chapel. Throughout the altarpiece, the light falls from the upper right corner, like sunlight in the chapel on a sunny afternoon in late spring or early summer. The degree of consistency in the lighting of the entire altarpiece is exceptional. In the central God the Father figure, the jewels in his mitre, the focal point of the sceptre's quartz rock crystal and all the points of light in the gold brocade fabric show a high degree of photographic accuracy.

Marc De Mey, who explored Alhazen's influence on Van Eyck, was the first to point out the painter's tour de force conceiving of the alternating rows of pearls and crystal beads hanging from God the Father's gold brocade sash inscribed Sabaut (Lord Sabbaoth His Name): while the former absorb the light from the window, the glass ones project wide reflections of it.

There are hundreds of examples, from the metallic reflection of the red banners on the breast armour of St. Michael and St. George, to the reflection of an entire window in the huge central sapphire of the principal angel's brooch in the Angels Singing panel. The tracery of that window was scratched out with the very tip of his brush, saturated with white paint, using the sgraffito technique.

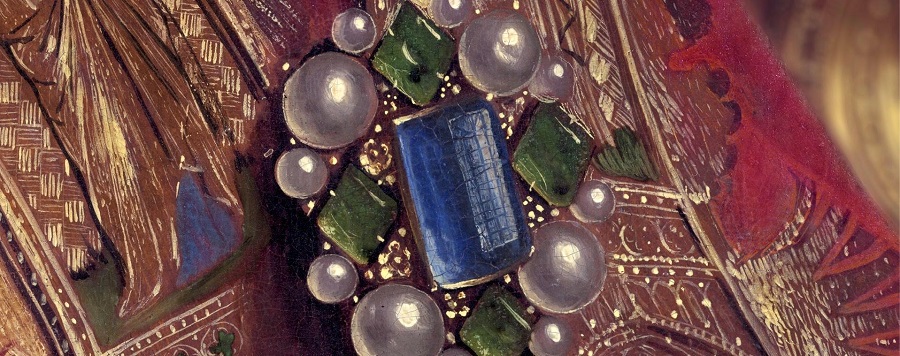

Angels Singing (detail), Ghent Altarpiece (1432), Saint Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent

What is also magical is the mastery the Flemish painter brings to painting the water flowing and splashing in the Altarpiece's fountain, as well as in The Virgin of the Fountain. Lighting plays a central role in its realism, but so does movement in the leap of every drop. The water flowing from the mouths of both sources is painted in fine, white, irregular and intermittent lines. It's as if Van Eyck had spent an afternoon with Bill Viola watching the water in his videos suspended in motion.

Jan van Eyck, Virgin of the Fountain (detail), 1439, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Flanders versus Italy, 1430

The exhibition pits Flemish paintings against their Italian contemporaries in a dialogue that reaffirms our question: What is it that makes Van Eyck seem like a comet flying over the 1430s in the European artistic firmament? Jacques Lassaigne and Giulio Carlo Argan have stated that the Renaissance was not a typical Italian movement that spread through other countries in a kind of progressive conquest, but rather a European phenomenon even though it happened differently in Flanders, Italy, France and Germany.

The beginning of the 15th century was witness to one of the greatest revolutions ever known in the history of painting. While Van Eyck paints the Altarpiece in Ghent between 1426 and 1432, Masaccio in Florence between 1426 and 1427 paints the Brancacci chapel, in the Carmine church. Italy favours form over concept; Flanders over experience. These two major works, created almost simultaneously by men so different in origin and tradition, are the pillars of a new painting.

Masaccio, The Expulsion From The Garden Of Eden (c. 1426-1427). Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

Masaccio continued to paint the walls of the Brancacci chapel al fresco with his Adam and Eve ejected and with anguished expressions in his Expulsion from Paradise but they cannot today touch their more serene, more disturbing namesakes in Ghent. There are, however, other revolutionaries in Italian optics: Gentile da Fabiano, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi ... with whom stylistic comparisons are inevitable, interesting: in Virgin and Child with Angels by Benozzo Gozzoli (1449-50) compared with van Eyck's Virgin of the Fountain (1439) the results from the same ultramarine pigment for the color of the Virgins' robes is very different: the tempera more opaque in the Italian and the crystalline glazes, much more intense in van Eyck. Also the enduring Italian penchant for gold leaf as opposed to the naturalistic focus of Eyck's painting which replaces the old-fashioned golden backgrounds with landscapes; the halos which cease to be large discs surrounding holy heads in favor of lighter golden rays; and gold objects which are no longer depicted with real gold but with yellow and brown paint to simulate light, form and texture.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Virgin and Child with Angels (c.1449-1450), Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail), Ghent Altarpiece

Absences

The penultimate room of the exhibition, dedicated to portraiture, is perhaps the most underwhelming. Tzvetan Todorov has said that when you walk through the halls of a large European museum, a radical change in the very nature of the paintings is visible as we pass, say, from 1350 to 1450. He explained that in northern Europe there was no Renaissance in the sense of a rediscovery of Greek and Roman civilization as a means of doing something new. Rather, the search for a new way to account for equally new experiences is what one observes. The common denominator in these changes is not the rediscovery of antiquity, but the discovery of individuality. Therefore, at that time, the individual portrait was invented, and has remained an art staple ever since. Men have taken the place of God in the system of universal symbolism.

Jan van Eyck, Baudouin de Lannoy (c.1435), Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museum, Berlin.

And so ends the exhibition, after the Crucifixions and the Annunciations, with the heroes of more recent times. There are six portraits of Jan van Eyck along with those of his Italian contemporaries Pisanello, Michele Giambono ...

Then, in the middle of the room, the only doubt about this extraordinary exhibition occurs to us: Where is Antonello da Messina with his delicate oils on wood? Moreover, where are the great Venetian Renaissance artists Vittore Carpaccio, Gentile and Giovanni Bellini?

We half-close our eyes and imagine ourselves in another room, solitary, painted blue, empty except for Man In A Red Turban (1433) by Jan Van Eyck facing Vittore Carpaccio's Man in a Red Beret (1485). Wouldn't that be a fight between Titans: a duel of two portraits gazing out at us, face to face.

As Jan van Eyck signed his motto: "Als ich can" (I did the best I could).

Left: Jan van Eyck, Man in a Red Turban, 1433. National Gallery, London. Right: Vittore Carpaccio, Man in A Red Beret, 1485, Correr Museum, Venice

Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution

Museum of Fine Art Ghent

Curators: Till-Holger Borchert, Maximiliaan Martens and Jan Dumolyn

Click here for a 360º Virtual tour of the exhibition

Virtual Live Tour conducted by Van Eyck expert and co-curator Till-Holger Borchert

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

French artist Christian Boltanski is an old acquaintance of the Spanish public. His 1988 Madrid exhibition – “El Caso” (The Case) - was a curious and disturbing suite of works expressly conceived of for the Reina Sofia Museum as a follow-up to his “Detective” exhibition of 1972. From articles in El Caso, a weekly journal of crimes and misdemeanors (1952-1997), and the Reina Sofia building’s origins as a hospital, the artist sought to create a world that would unnerve viewers finding themselves surrounded by portraits of the murderers and victims featured on newspaper pages alongside starched white sheets, folded and piled up as if by nurses.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

French artist Christian Boltanski is an old acquaintance of the Spanish public. His 1988 Madrid exhibition – “El Caso” (The Case) - was a curious and disturbing suite of works expressly conceived of for the Reina Sofia Museum as a follow-up to his “Detective” exhibition of 1972. From articles in El Caso, a weekly journal of crimes and misdemeanors (1952-1997), and the Reina Sofia building’s origins as a hospital, the artist sought to create a world that would unnerve viewers finding themselves surrounded by portraits of the murderers and victims featured on newspaper pages alongside starched white sheets, folded and piled up as if by nurses. He created a symbolic and metaphorical world from his own particular understanding of existence where subjectivity is a blurred line between erased , anonymous images and the horror or the evil that can be concealed.

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

With that exhibition and many others, both before and after, Boltanski has become an artist of note and now, thirty-five years after his first retrospective at the Museé National d'Art Moderne in Paris, the Centre Pompidou pays him homage with a large exhibition featuring the themes that have been his constant companions since 1967: collective memory, the passage of time, loss, oblivion, forgetting, chance and, above all, the human condition.

In his work, Boltanski projects new light onto all that is known, giving the historical fact of the Holocaust a new interpretation by framing it within his quest to interrogate everything, from feelings about existence to an existence that does not respond.

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

He reminds us of the ephemerality of life versus the definitiveness of death and does so using photographs, videos, tin boxes stacked or embedded in walls like cremation urns in niches, some of them with small portraits, mostly of children. But also with display cases, newspaper clippings, notes, family photos, black monoliths that recall funerals, curtains enclosing tiny spaces, black clothes forming a morbid mountain of death. All this within a labyrinthine journey around the museum that never stops asking questions. Spirits lost in a forest of souls.

Dim lighting, disturbing noises that at times sound human and challenge the silence of the viewer in the face of so much desolation. The staging corroborates and enriches the artist's intention with each of the exhibits, all of which become channels of communication.

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

“Nothing answers us, but that silence, the voice of that silence, we hear it, and it terrifies us, 'the eternal silence of these infinite spaces' that Pascal speaks of.” Emmanuel Levinas

Boltanski once said that his exhibitions create experiences, seek to move the visitor and let them come to their own conclusions. Never a truer word was spoken.

Christian Boltanski: Faire son temps

Centre Pompidou

13 November 2019 - 16 March 2020

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Christian Boltanski: Doing One's Time - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Art is in everything, art is in life and it expresses itself on every occasion and in every country. Charlotte Perriand, iconic figure of twentieth century design, demonstrates yet again the importance and influence of her work in a grand exhibition on display until February 24 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Perriand changed the way we inhabit domestic spaces, creating a world full of possibilities unfettered by traditional notions of what a home should be.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Left: Charlotte Perriand at La Vallée, circa 1930 © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP. Right: Charlotte Perriand reclines on « Chaise longue basculante, B306 » (1928-1929) – Le Corbusier, P. Jeanneret, C. Perriand, circa 1928 © F.L.C. / ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP

“Art is in everything, art is in life and it expresses itself on every occasion and in every country.” Charlotte Perriand

Charlotte Perriand, iconic figure of twentieth century design, demonstrates yet again the importance and influence of her work in a grand exhibition on display until February 24 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Perriand changed the way we inhabit domestic spaces, creating a world full of possibilities unfettered by traditional notions of what a home should be. She made use of technical skill, industry and the most advanced materials for her designs. Parts from bicycles, cars and even airplanes were a source of inspiration that would lead to her becoming, over time, a pioneer in the mass production of her own designs.

Almost the entirety of the Frank Gehry-designed gallery has been given over to the exhibition on a chronologically arranged route that welcomes the visitor with a large painting by Fernando Leger, “Le transport des Forces”, and two of Perriand's most iconic pieces, the Chaise Longue basculante LC4 and the B302 Swivel Chair, long and erroneously thought to have been designed by Le Corbusier alone.

As well as Leger, other artists features alongside Perriand throughout the whole tour are, Picasso, Laurens and Delauney.

Building modernity, exploring Nature and engaging with other cultures are just a few of the highlights of the Exhibition that define the work of an intelligent woman devoted to her ideas and profession and whose unwavering dynamic vitality endeared her to everyone she met. A tireless traveller, she absorbed life with such intensity that it is sometimes difficult to keep pace with her.

In 1926, a recent graduate and excited by Le Corbusier's theoretical work on new cities and alternative ways of living, she knocked on the door of the studio that the renowned Swiss architect shared with Pierre Jeanneret, the outcome of which was that infamous quote: “Miss, we don’t embroider cushions here”. A year later, Le Corbusier recanted and offered her a contract, having seen, at the Salon of Decorative Artists, her piece Le Bar sous le toit, a cocktail bar that Perriand had designed for her own apartment. Thus began an intense collaboration that would endure throughout the lives of these two innovators. Perriand writes in her memoirs that her role in Le Corbusier and Jeanneret’s studio was to bring the ideas of the two great architects to fruition. She was a practical woman and one capable of solving any problem with her vivid imagination, filling what Le Corbusier called “machines for living” with humanity. In 1952, Le Corbusier called her to design the interiors of what are known as his Unité d’habitation housing developments in Marseille and Berlin. The result can be seen in the Exhibition and illustrates that she knew precisely how to convert those minimal spaces into cosy places, incorporating the first ever compact modular kitchen prototype.

One of the key pieces in the Exhibition is a recreation of the interiors project for the 1929 Autumn Salon, L'Équipement Interieur d’une Habitation, which she created in collaboration with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret. Here, the visitor can interact with the furniture and understand how the arrangement of objects in a space creates the ambience that turns a home into a comfortable one.

In 1929, the pricking of her social conscience led her to participate in the creation of the Union of Modern Artists (UAM), in which Mallet-Stevens, Miró, Calder, Delauney and Chareau also participated. What they sought was the coming together of all arts to respond to the political and societal problems of their time. The Republic of Spain pavilion at the 1937 Paris exhibition was a perfect reflection of the aims of UAM - architecture, sculpture, painting and photography together in a joint portrayal of the tragedy of war. Its curator was the architect José Luis Sert, a great friend and collaborator of Perriand’s, who is remembered in the exhibition with a display of his photographs taken during the Spanish Civil War and a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica, among other items. Both architects shared the same social concerns and collaborated on the design of minimalist housing. In 1933, they participated in the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) where the Athens Charter was drawn up, the widely-known manifesto on optimal conditions for urban living.

A full-scale model of another of Perriand’s iconic works, 1934’s The House On The Edge of the Water, rests on stilts outside the Foundation on and beside a water feature so that visitors can visualise the meaning of the project, intended as a holiday home for families with little money to spare. A kind of self-assembly cabin than can be dismantled, supported on stilts and divided into two symmetrical spaces: one, the living area and the other to sleep in, both with sliding doors opening onto a terrace protected by a canopy collecting rainwater. Again, Perriand is thinking about functionality and aiming to reach the most needy by building a world that is simpler, more humane and closer to nature.

She was also an accomplished photographer who scrutinized Nature through her camera lens, finding solutions for many of her creative ideas there. The sea and the mountains were recurring themes in her snapshots and the inspiration for a series of projects on mountain shelters. In 1938, her Tanneau Mountain Refuge, measuring eight square metres and sleeping six people, was built. “I love the mountains deeply,” she said. “I love them because I need them. They have always been the barometer of my physical and mental equilibrium.”

Her time in Japan and Indochina are very well illustrated in the Exhibition with designs incorporating elements from the East such as indigenous types of wood, bamboo, lacquer and fabrics that reinforced the links between creation and tradition. Brazil, where she got to know other renowned architects and the exuberance of their designs, was another turning point in her career.

The crowning moment of her career would come with the Les Arcs project, a huge apartment complex in the French Alps, with a sleeping capacity of 30,000. Perriand, in a display of ingenuity, developed what has been called minimalist compartments or cells. The interiors were mostly built from prefabricated pieces and boasted large windows with stunning views that brought nature in from outside. A large model serves to help the viewer understand Les Arcs as the culmination of the whole repertoire of Charlotte Perriand’s ideas.

The tour ends with Perriand's last ever commission – 1993’s Maison de Thé for UNESCO’s Paris headquarters: a wooden circle supporting eighteen bamboo canes creating a 4.5 metre high space covered with a domed canopy of leaf silhouettes. A delicate, organic work to celebrate the Tea Ceremony.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World

Louis Vuitton Foundation

2 October 2019 - 24 February 2020

(Translated form the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Le Monde Nouveau de Charlotte Perriand - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

On a scale of difficult to … how does one even begin to guess what was going through Leonardo da Vinci's mind on seeing a woodpecker for the first time? "Describe its tongue," the painter asks himself in one of the many little notes scribbled in the margins of a notebook ... "The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril." In the concluding pages of his book, Walter Isaacson (New Orleans, 1952) establishes an imaginary dialogue between his reader, Leonardo and himself in which he offers us a clue: "There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. But I thought maybe that you would want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.”

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Lady with an Ermine (1490), National Museum of Krakow

On a scale of difficult to … how does one even begin to guess what was going through Leonardo da Vinci's mind on seeing a woodpecker for the first time? "Describe its tongue," the painter asks himself in one of the many little notes scribbled in the margins of a notebook ... "The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril." In the concluding pages of his book, Walter Isaacson (New Orleans, 1952) establishes an imaginary dialogue between his reader, Leonardo and himself in which he offers us a clue: "There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. But I thought maybe that you would want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.”

This is at the end of the book and also at its heart. The word "curiosity", repeated throughout its 624 pages, is one of the axes on which the description of the genius that was Leonardo (1452-1519) revolves and why the author acknowledges that this biography is based not on his paintings but on his notebooks. He believes the 7,200 pages of miraculously preserved notes, drawings and sketches are what hold the key to the enigma of "the most curious man in history", as Kenneth Clark dubbed him.

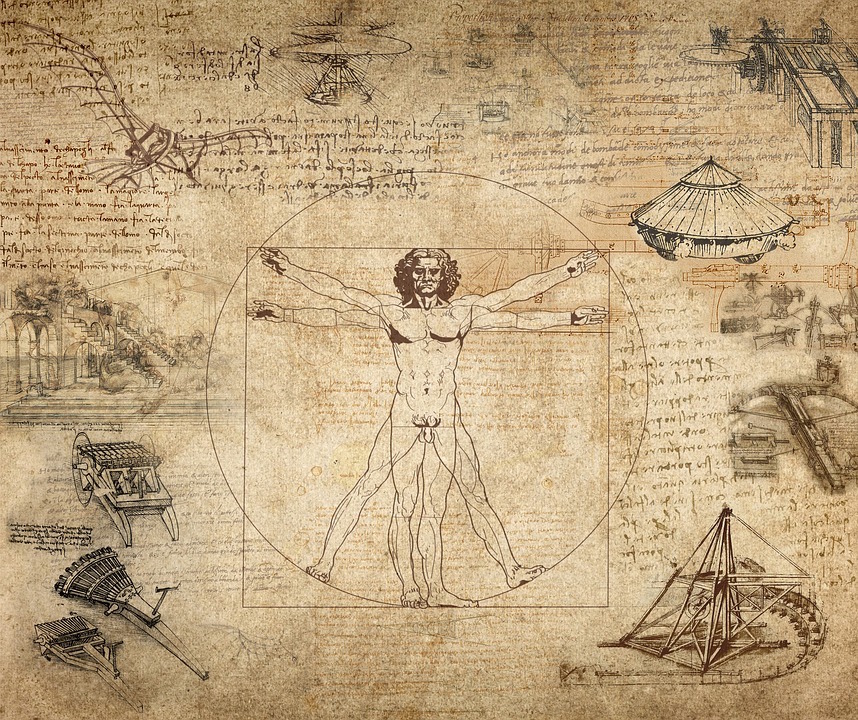

Vitrubian Man (1490), Accademia Gallery, Venice

Leonardo's fascination with the world and his observations of it were what predominated his thoughts and unbounded imagination. The notebooks are the record of a stubborn, daring, unstoppable mind. The author wants to breathe all of this into us, as if, through a kind of mental gymnastics, we readers could also grasp some of Leonardo's brain. The genius of one of history’s greatest visionaries was born of abilities that we ourselves possess and are also able to stimulate. His curiosity, like Einstein's, was mostly concerned with phenomena that wouldn’t even occur to most people over the age of ten: How do clouds form? Why do our eyes only see in a straight line? What makes us yawn?

Isaacson, a former Time Magazine editor, is obsessed with talent. The New Yorker writes that this book is a study on creativity, how to define it, how to achieve it. And this is what led its author to choose the figure of Leonardo to follow on from his previous biographies of Einstein, Kissinger and Benjamin Franklin, all of whom established connections between different disciplines: they knew how to link observation and creation. In his penultimate biography, Isaacson quotes Steve Jobs, for whom Leonardo was a hero: "He saw the beauty in both art and engineering and his ability to combine them made him a genius.”

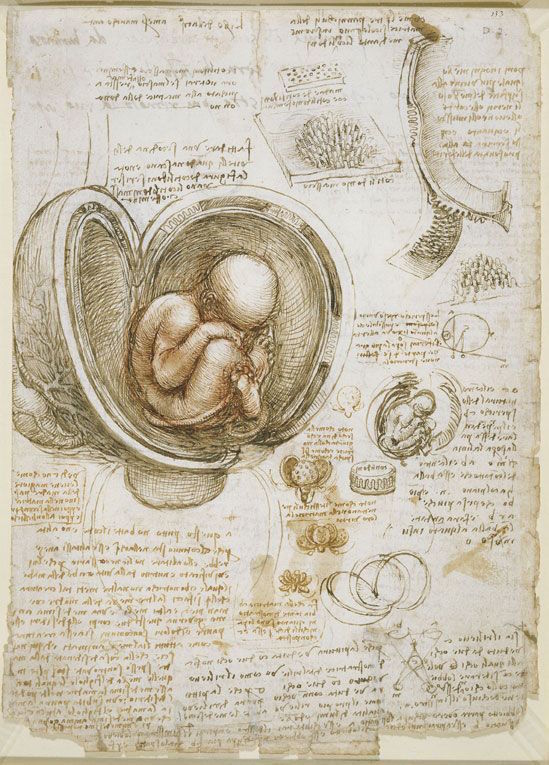

Foetus in the womb, inspired by the dissection of a pregnant cow (circa 1511), Royal Collection, Buckingham Palace

The desire to know

This book portrays, essentially, a man consumed by the desire to know. A son born out of wedlock, vegetarian, homosexual, fashion buff with a penchant for dressing in pink and linen, his love of animals preventing him from wearing anything dead on his person. But did he ever live with his mother? Who did he love and, above all, who loved him? There are chapters dedicated to his childhood and his death in the arms of Francis I in Amboise.

It would seem that 1452 was a fine time for a child with such skills to be born: Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. The Ottoman Turks were about to invade Constantinople, which led to mass exile to Italy by scholars laden with manuscripts containing the ancient wisdom of Euclid, Plato, Aristotle ... And just a year separated the births of Christopher Columbus, Americo Vespucio and Leonardo.

La Belle Ferronière (1480-1495), The Louvre, Paris

Leonardo had almost no formal schooling: self-taught, from a young age he would tie a notebook full of enigmatic and invariably undated writing to his belt. He wrote from right to left, thus producing his specular calligraphy - "It should be read with a mirror," Vasari wrote - using his left hand to move backwards without smearing the ink. The pages are full of wild leaps, from the description of a mechanical problem to the curl of a lock of hair. However, it was there in those pages that he wound up weaving the key to his art: the interconnection between Nature, the human being and the Earth. He accompanied his drawings with texts whose shapes can be found similarly in branching trees, the arteries of the human body and in rivers and their tributaries ... whilst at the same time, in some page corner, he jotted down the formula for hair dye. This tower of Babel, this medley of multicoloured splashes of ink, leads us to marvel at a universal mind which scoured the arts and sciences with abandon and awe and in so doing perceived the connections that occur in the universe.

The Virgin of the Rocks (detail) (1483-86), The Louvre, Paris

Birds, waves

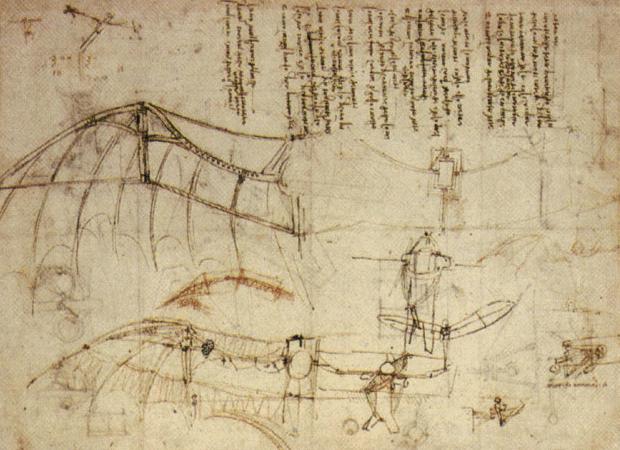

And so Leonardo set to observing birds, researching how they flew and even the possibility of designing machines that would allow humans to fly. He painted the elegance of the birds as they turned, soared and manoeuvered in the wind. He pioneered the use of arrows. No scientist before him had shown how birds were able to remain aloft. And he corrected Aristotle: "In order to give the true science of the motion of birds within the air, it is necessary first to give the science of the winds, which we shall prove by means of the motions of water within itself." Not only did he understand fluid flow patterns and their dynamics but his ideas predated those of Newton and Galileo. He also observed the flight of a partridge: "When a bird with a wide wingspan and short tail wants to take off, it will lift its wings with force and turn them to receive the wind beneath them."

Articulated wings, emulating those of birds

In the meantime, he was also studying the Earth as a planet. In 1508 he summed it all up in his notebook, the Leicester Codex. In it he wondered: Why do springs originate in the mountains? Why do valleys exist? What makes the moon shine? How did fossils make their way up mountains? What makes water and air whirl? And the most surprising, why is the sky blue?

The current owner of the Leicester Codex is Bill Gates so, although Isaacson makes no reference to it, some of its digitalized pages are used as screensavers by Microsoft.

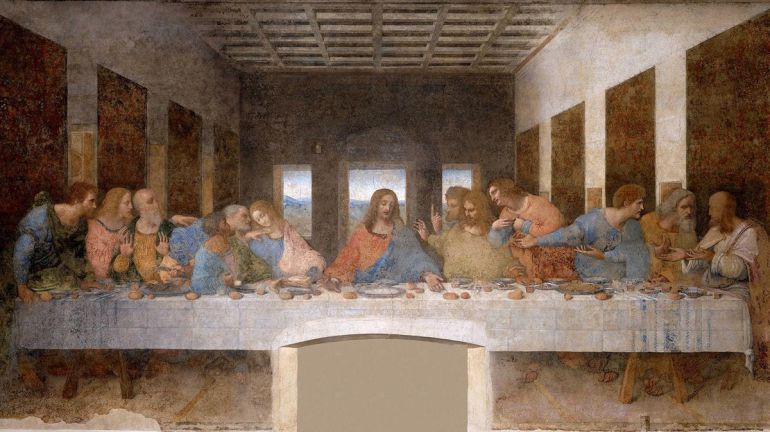

His studies on the movement of water also led him to understand that of waves. He noticed that they don't necessarily push water forward. Sea waves and those caused by a stone falling into a pond advance in a certain direction but all these what he called "tremors" do is cause a momentary swell before returning to their starting point. He compared them to the undulations caused by the wind in a cornfield. He even believed that emotions could also spread in waves. One element of the narrative of the Last Supper is the waves of emotion that Jesus causes after saying, "Truly I say unto you that one of you will betray me."

The Last Supper (1495-97), Refectory of Santa María della Grazie, Milan

Also blended seamlessly through Isaacson's pages are paragraphs on many of Leonardo's works of art, his discoveries, his techniques and the description of his paintings from Salvator Mundi and the Virgin of the Rocks to the Man of Vitrubio and The Last Supper. In Ginevra De'Benci's portrait, Leonardo portrays a melancholy young woman against a background of juniper bushes (Ginevra meaning juniper in Italian). Leonardo applied not old-fashioned tempera but hundreds of layers of oil paint so as to make Ginevra's curls and the button at her neck appear to be forged from light. And let’s not forget the similarity of the colours of her dress to the landscape in the river water and the shadows cast by trees. "Ginevra has remained at one with the land and the river that binds them."

Ginevra de' Benci (1474-76), National Gallery of Art, Washington

Human anatomy

In 1508, in a Florentine hospital, he would strike up a conversation with a hundred-year-old man who was to die a few hours later. Leonardo dissected his body. On one of his notebook pages, above several sketches of the muscles and veins of a partially skinned corpse, he made a note of the centenarian’s face. Then, over the next 30 pages, he proceeded to make notes of what he saw. His rudimentary instruments for dissection enabled him to discover, layer by layer, the body while the body, being untreated, decomposed. First he showed the elderly man’s superficial muscles, then he removed the skin and showed the inner muscles and veins. Of all the related muscles and nerves, the ones controlling the face seemed to him the most worthy of study. He drew a cross-section of the spinal cord and all the nerves leading from the brain. He ascertained from the corpse that it is the cheek muscles that move the lips. They were the first known examples of the scientific anatomy of the human smile. At the time, Leonardo was working on the Mona Lisa.

Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster, 2018

624 pages

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Leonardo Da Vinci ~ an infinite curiosity - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

This exhibition bombards us with a storm of ideas. It is a gauntlet thrown down to us by the Royal Academy and one that Gormley takes up, with all his weapons and from all sides: with lead, steel, seawater, a little blood from his veins and a battalion of iron men, dozens of soldier Gormleys. It has been four years in the making during which time, for the positioning of each and every piece, every conceivable permutation has been tried. Also during that time, the building’s architecture has been subjected to extremes, pushing it to its very limits: walls supporting massive weights, average-sized rooms housing pieces the size of something from another world, from Gulliver’s Travels, that balloon out against the doors, against the corners, while, in the adjoining room, the floor has been turned into a pond and is flooded with water.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Subject (2018), Royal Academy of Arts, London

This exhibition bombards us with a storm of ideas. It is a gauntlet thrown down to us by the Royal Academy and one that Gormley takes up, with all his weapons and from all sides: with lead, steel, seawater, a little blood from his veins and a battalion of iron men, dozens of soldier Gormleys. It has been four years in the making during which time, for the positioning of each and every piece, every conceivable permutation has been tried. Also during that time, the building’s architecture has been subjected to extremes, pushing it to its very limits: walls supporting massive weights, average-sized rooms housing pieces the size of something from another world, from Gulliver’s Travels, that balloon out against the doors, against the corners, while, in the adjoining room, the floor has been turned into a pond and is flooded with water.

However, here in this tension is where, constant and dense as a thread of light, Gormley's discourse lies. In that sense, this doesn’t seem like a conventional retrospective but a statement of the principles of the artist who, from the start, has persevered in the continuity of his incessant, unsettling question, like a gong, like a boot kicking metal and in his obsession with getting us involved, shaking us up, waking us up: "The body is more a place than an object for me: body "in" space and body "as" space. Come with me, close your eyes, look inside your body, into that darkness where the limits of space are lost, where we acquire the infinity of the cosmos." That's the key, that’s Antony Gormley's war cry.

The courtyard of the Royal Academy, with its neoclassical facade, is presided over by the statue of its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. These days, the portraitist and promoter of the “Grand Style” in painting, looks askance at a tiny object at his feet: “Iron Baby” (1999) is the sculpture of a newborn, life-sized and curled up on the ground as if it were her cradle - it is based on Gormley's daughter, six days after her birth. The artist says: "Its density suggests energy potential like a small bomb. The material is iron (concentrated earth), the same as the core of our planet.” This projectile-piece sets the tone of the exhibition.

Iron Baby (1999), Annenberg Courtyard, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Antony Gormley was born in London in 1950 into a devout Roman Catholic family: he was baptized with a name whose initials make up A.M.D.G. (Ad maiorem Dei gloriam -To the greater glory of God) which is the Latin motto of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits): "My name is Antony Mark David Gormley and I wasn’t called that by accident." From the age of six, he had to obey the strict rules of his afternoon nap: he would go up to his small bedroom where it was hot, lie down and not move, his eyes closed, while the light flooded his bed mercilessly. In that claustrophobic environment, he felt imprisoned in his incandescent cage, alone with his eyes. Gradually, he began to focus on that enclosed, oppressive space, transforming it into a different place: dark, cool, floating in a deep, blue infinity. Sixty years later, he is a sculptor whose work wrestles with the concept of what it means to inhabit the human body.

Gormley boarded at a Benedictine public school and travelled to Lourdes as a volunteer, all of which shattered his Catholic faith. After graduating from Cambridge, he joined the hippy trail, travelling through Turkey, Syria and Afghanistan to India: "the place where things started to make some sense." He spent two years studying Buddhism: "Passion for meditation took me to a place I’d already been to as a child."

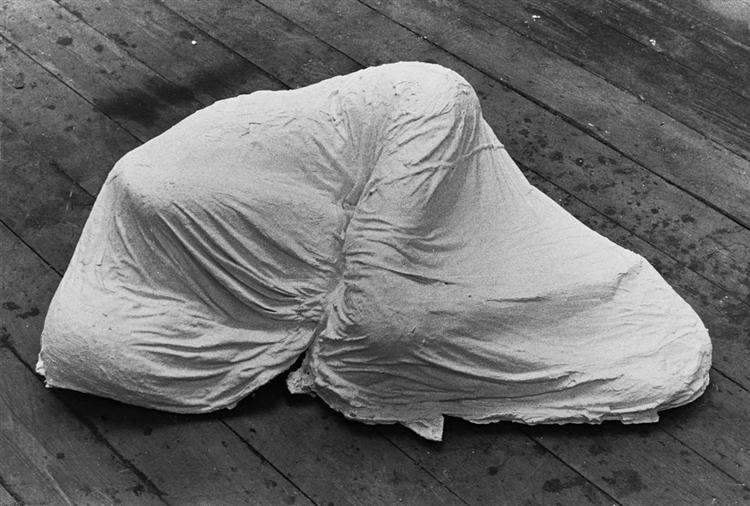

His experience in India planted the seeds for his early sculptures. Sleeping place (1974) is the silhouette of a man lying down in the foetal position, covered by a white cloth. "For two weeks I wandered around Calcutta. The streets were made up of noise, the suitcases, the car crashes, the food stalls on the ground, the rickshaws ... and in the midst of all that were these bodies just lying there, not moving, covered up and noone knew if they were dead or alive. Sleeping Place was my way of turning that experience into an object."

Sleeping place (1974)

Since 1981, Gormley has been working with the body and choosing his as the nucleus for everything. For the next 15 years, Vicken Parsons, his wife, accomplice and only assistant, wrapped the artist's naked body in plaster mesh in different poses, leaving only a hole for his mouth, trimming it and then freeing him from the plaster casing. And so began Gormley’s artistic hallmark, an army of iron men who today populate the world from the English coast to the rooftops of Manhattan. These "bodycase" sculptures - of which Lost Horizon I (2008) is the piece featured in this exhibition, consisting of 24 figures all pointing in different directions from the walls, floor and ceiling, questioning the perception of what is above and what is below - evolved thanks to cutting-edge infrared technology and a custom-made computer program which allowed him to take his dimensions and postures even further, delving deeper into abstraction. Increasingly, schematic "men" began to emerge whose bones, muscles and skin were decoded into computer or industrial forms, physical pixels made of rusty iron, bricks of metal that, like Lego, constitute beings without a name, without an identity. These are the Slabworks (2019) in Room 1.

Lost Horizon I (2008), Royal Academy of Arts, London

Slabworks (2019), Royal Academy of Arts, London

Antony Gormley has just turned 70 and the Royal Academy is thus honouring his trajectory here. However, Gormley’s works, as open-air sculptures, grow with an amplifying force that pierces urban and rural landscapes like acupuncture needles: beaches, deserts, Italian palaces and industrial England’s chimneys ... The sculptor leaves his solitary men there, like a forest of questions, forcing us to understand that place in a very different way. In the words of Simon Schama: "They are actors, not statues."

Another Place (1997), Crosby Beach, Merseyside, Great Britain

Gormley also wanted to give voice to those who did not have one - "One&Other" (2009) with 2,400 volunteers occupying the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square - and "Sculpture for Derry Walls" (1987) was his link to 'The Troubles' in Northern Ireland. Two back-to-back figures in symbolically Christian cruciform form, cast in iron to withstand the impact of bullets, were placed at strategic border points between Catholics and Protestants: "As soon as the sculptures came down from the cranes, a crowd of young people huddled around them, spitting at them. A young man on my team flew at them with a hammer at lightening speed. I will always remember that moment. Those gangs burned our sculptures, hung tires from their necks and set them on fire. The next morning the remains of the scorched tyres looked like crowns of thorns."

Sculpture for Derry Walls (1987), Derry, Ireland

A connection with the spectator has also led him to invite the public to collaborate on the creation of his work. "Field" (1990) is an ocean of small clay figures made in three weeks by a family of brick builders outside Mexico City: "Every time I've done "Field", I've used local people and materials. That time I gave them some very basic instructions: Take a piece of mud, shape it with your hands, make two incisions for the eyes and see what becomes of it, let it make its own shape, which will be unique. What turns out, or better said, what is freed when you give a group of people a common goal? The result is magical."

The first time he did "Field", there were over 1,000 figures. When he did "Field for the British Isles" (1993), the army of small mud men surpassed 40,000. "I tried to physically offer a voice to those who did't have one. I grew up in the 1960s, in an orderly world where ordinary people were gradually reaching positions of power. That's the spirit of "Field", filling up every last inch of a museum so the pleasant experience of being in a museum is transformed into a confrontation with the accusatory looks of thousands of eyes challenging us," Gormley explains.

Field for the British Isles (1993), St Helens, Liverpool, Great Britain

In 1994, Gormley won the Turner Prize which brought him recognition and an infinite launch pad for taking on larger projects. "Angel of the North" (1998) is a 20m high totem pole of 200 tonnes of angel-shaped steel. Its deployed wings stretch as wide as a Jumbo jet’s. Its location, just off the busy A1 motorway near Gateshead, makes it one of the most viewed works of art in the world.

Angel of the North (1998), Gateshead, Great Britain

The spirit of these works can be felt to vibrate throughout the 13 rooms of the exhibition which also display Gormley's drawings and which, like a 21st century Leonardo da Vinci but tinged with blood, oil, earth and flaxseed oil, demonstrate a sculptor's obsession with drawing. They are like diamonds shooting out hard, fast and direct like arrows from the neurons of his ingenuity.

Mould (1981), Private collection

This exhibition is a co-production between spectator and creator. The sculptures demand our physical and imaginative participation: we are obliged to bend down, crawl and lose ourselves among them. Also fascinating is the play on scale with works the size of the palm of one’s hand beside other colossal ones. "Clearing VII" (2019), composed of miles of coiled aluminum tubes tracing an arch between the floor and ceiling and wall to wall, is a "drawing in space" that envelops the visitor. "Host" (2019) fills a room with sea water and mud, evoking the depths from which life emerged. "Matrix III" (2019) is a huge dark cloud of rectangular steel grilles suspended from the ceiling. Although some of his new pieces are abstract, his reference point is always the human body. Da Vinci drew his Vitruvian Man in 1490: "Vitruvius established in eight heads the proportion of man and also that the distance from the chin to the forehead should measure the same as the hand," Gormley says as he moves towards the Matrix III mesh to demonstrate.

Matrix III (2019), Royal Academy of Arts, London

On these last days of summer light, it is still possible to view Gormley’s “Sight” installations on the island of Delos. Like modern-day sentinels, twenty-nine of his iron men defend this floating rock in the middle of the Aegean, whose name means 'The Visible' after Zeus offered it to Leto, his mortal lover, to give birth to Artemis and Apollo. Today, 5,000 years later, sees the first intervention by an artist. His sculptures greet us from strategic points: the seashore, surrounded by poppies on the ground between pillars or as strange companions to the marble gods in the museum …. while having an emotional conversation through the millennia of time. According to Martin Robertson, a British specialist in Greek archaeology, it was on this island that a marble statue depicting a woman appeared in the middle of the 7th century BC from the shrine of Delos. In the skirts of the figure reads an inscription in verse telling us that it was dedicated to Artemis by Nikandre of Naxos. That was the start of monumental sculpture in Greece.

Sight, (2019), Delos Island

But Delos is also inhabited by Gormley sculptures that are more in keeping with that other abstract canon of his - pixelated men, which are surprisingly integrated into what remains of the island's architecture today: catalogued ruins laid in rows of stone blocks by archaeologists. In this sense, it is an objective correlation of the digital age, in which information comes to us in bits that we reconstruct to create an image: "That was the original idea that coordinated the syntax of this exhibition, from these decoded bodies, like material shadows of a living body," says the sculptor.

Sight, (2019), Delos Island

Like David Hockney, Gormley belongs to that group of artists who have dedicated part of their lives to the writing of a discourse on the History of Art. In the BBC documentary 'How Art Began' and with the emotion of an English thespian, the sculptor tours the Paleolithic caves of France, Spain and Indonesia in search of humankind’s first artistic trace and the answer to a question: what triggered in homo sapiens the need to leave their footprint in time? Thus, installations such as "Sight", or "Still Standing" (2011) from the Hermitage’s permanent collection, have allowed him to confront us with his premise using the dialogue of his oeuvre with classical statuary. For Gormley, from Greece to the 19th century there was a single discourse in sculpture: the idealization of the human body. He insists that today times are different, that his work demands the participation of the viewer, that his empty bodies must be filled out by our sensations. "Cave" (2019), the jewel in the Royal Academy’s crown, is a sculpture of architectural proportions, an enormous body transformed into geometric caves with an entrance and exit. What Gormley aspires to is that we enter it and live inside its stomach, its limbs like tunnels of light and feel the cold and anguish inside the head of this Hulk, bursting into steel buckets on the ground. "I try to give the new language of modernity to the body that was rejected earlier as something classical. What I want to do concerns the abstract body, the one that corresponds to the language of Malevich, Picasso... and from there to Donald Judd and Sol Lewitt." Gormley and the past are as a propulsion of his sculpture into the future: two sensations that merge into a single victory.

Antony Gormley

Royal Academy of Arts

Burlington House Piccadilly,

London W1J 0BD

Curator: Martin Caiger-Smith

21 September - 3 December 2019

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Gormley at the Royal Academy: a discourse in iron - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Guerrilla Girls are a collective of anonymous artists who emerged during the 1980s in the United States with the aim of protesting the sexism suffered by women in the art world. Their first appearance dates back to 1985 when they demonstrated outside the Museum of Modern Art in New York to highlight the scant female representation in the gallery’s contemporary art exhibition, ‘An Internacional Survey of Painting and Sculpture’. Of the 169 artists who participated, only 13 of them were women.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Pavilion 16 of the former slaughterhouse ‘MATADERO’ in Madrid, now converted into a complex of spaces for contemporary art, ran an exhibition from January to April 2015 showcasing the work of Guerrilla Girls, a feminist art collective, and commemorating all thirty years of their activist output so far.

Guerrilla Girls are a collective of anonymous artists who emerged during the 1980s in the United States with the aim of protesting the sexism suffered by women in the art world. Their first appearance dates back to 1985 when they demonstrated outside the Museum of Modern Art in New York to highlight the scant female representation in the gallery’s contemporary art exhibition, ‘An Internacional Survey of Painting and Sculpture’. Of the 169 artists who participated, only 13 of them were women. Since then, they have not stoppedin their denouncements of the systematic lack of recognition faced by the female sex, not only in the artistic but also in business and political spheres. They reclaim the conspicuousness by their absence of women in the art world and condemn the lack of support from public institutions for their work as well as the widespread invisibility in the cultural and social spheres. They seek not only equal rights but equal opportunities in a world where men set the rules of the game. They want an "I" beyond the dichotomy of sex and gender. Biological sex has become a social genre that discriminates against and relegates women.

Possibly what stands out most about the Guerrilla Girls’ retrospective is how it raises awareness that feminism, as a protest movement for liberation, has ceased to be present in today's public discourse, as compared to the interest it sparked in the 1980’s when it became visible not only on the streets but also in academia with the emergence of the first Women's Studies courses at universities in Britain, France, Italy and the United States. Its presentation now in Madrid’s artistic circles, and previously in Bilbao, constitutes a great opportunity to reflect on those certainties that have accompanied those great stories in art history (invariably written by men) and the possibility of returning to them with a greater capacity for analysis and having a better interpretation of "woman” as a social subject at our disposal.

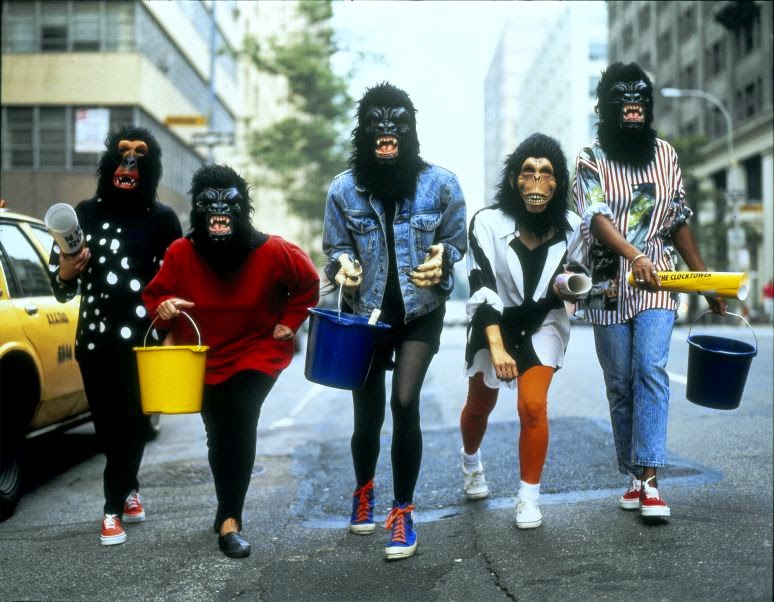

The gorilla masks they wear in public are the identity marker of a group who seek anonymity for their members and use, instead of their real names, those of illustrious women who have disappeared into oblivion. All we know is that their aliases are those of female artists or those linked to the art world. Their image serves as a vehicle for their own particular discourse, becoming the subject and object of their protests. Sexual discrimination, the shortsightedness of the artistic world, the paradox of believing that art is at the forefront of the societal avant-garde, the use of statistics as scientific findings and wake-up calls alerting us to other marginalized groups are just some of their battle cries.

The Guerrilla Girls’ most representative work is their posters, of multiple sizes, and varied designs, full of ironic messages that bring a smile to the visitor’s face and often also a reflection on the power of the written word in the age of the image and an opportunity to free it from its normative chains. Interestingly, as I have already pointed out, statistics are one of the weapons this group uses to emphasize its exposes on a recurring basis. An example of this is a 1985 poster with the following caption, “These galleries show no more than 10% women artists or none at all.” And another from 1989, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum? Less than 4% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but, 76% of the nudes are female.” The poster is an easy way of attracting the visitors’ attention and, in order to do this, the activists seek to mazimize their voices by positioning their messages in the most conspicuous places in museums and art galleries. Participation in forums, publishing books, magazines and documentaries, giving interviews and seeking out followers for the cause are other forms of activism. The collective no longer has room for any more members but it does encourage us to support their demands from wherever we may be.

Xabier Arakistain, curator of the exhibition and a great connoisseur of women's issues, has brought together practically all of the group's work since their formation and invites the viewer, in date order, to understand these women’s processes of creation and their forms of protest. Their message has been disseminated across the world and it is possible that their ironic and humoristic oeuvre of complaint, accusation and social criticism will serve to sensitize the public and change their perception of women in the arts.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Guerrilla Girls - - Alejandra de Argos -