Author: Elena Cué

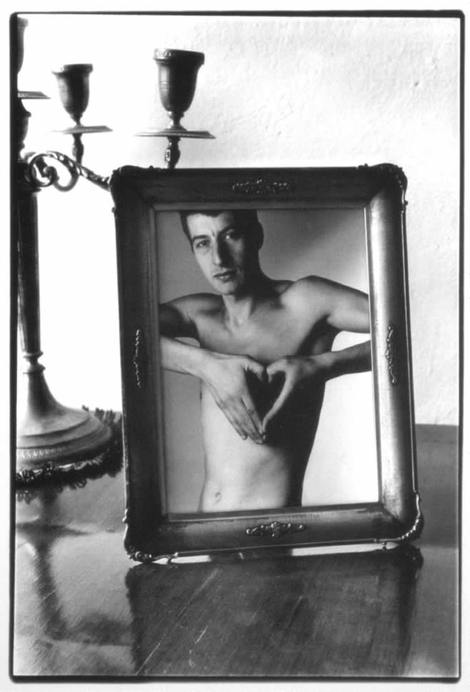

Maurizio Cattelan was born in Padua, Italy in 1960. Internationally, he is considered as the most relevant Italian artist in the contemporary art world. As a self-taught artist, his career began in 1989 with a black and white photograph titled Family Syntax; a framed self-portrait in which he appears forming a heart with his hands over his naked chest. He has previously collaborated with a gallery in Milan working on furniture design.

Elena Cué: Your work is anarchic, irreverent, absurd and provocative to the extreme. It is often a dramatic satirical representation. One could say he is post-Dada who questions all established values; religious authority, our society, materialism and contemporary art itself. His attitude towards established authority, and thus towards its political and religious representatives comes from his school days. His work is cast as a dark comedy so that each individual may develop their own interpretation.

Do you approach your own existence with the same sense of humor?

Maurizio Cattelan: I think humor and irony include tragedy in itself, as if they were two sides of the same coin. In both cases, laughter is a Trojan horse to enter into direct contact with the unconscious, strike the imagination and trigger visceral reactions. If humor of certain works was enough to pull of anger, fear and amazement out of everyone, the psychoanalysts would be in disgrace ... shame is not enough.

Elena Cué: It is difficult to create a concise profile of Maurizio Catellan. How would you define yourself?

Maurizio Cattelan: I think that the world needs to find a provocateur or a scapegoat, from time to time. I just found myself in an odd place in a fancy moment. No matter what they say, I still think to be the most boring person I know.… I would fall asleep trying to define myself!

Elena Cué: The artist's work is simultaneously highly considered, as well as being an extension of what lies latently within their subconscious. This pure kind of thought; dark and impossible to decipher, becomes very symbolic if it reaches the surface through the creative process.

Has art helped you know yourself better? What do you get out of it?

Maurizio Cattelan: You should ask it my psychoanalyst, if only I had one. Probably I never needed one because my job was a kind of therapy: every work I made was a part of me I got rid of while creating it. Happiness is not about gaining something, it’s more about getting rid of the darkness you accumulate. Apparently, since I retired the treatment is over: I’m not sure it worked, but in the meanwhile I produced a lot of crap!

Elena Cué: You've said you don't consider yourself a conceptual artist, that you don't think.

Is that another joke?

Maurizio Cattelan: I feel I’ve never started being an artist, maybe that’s why it was so easy to decide to retire...I constantly question myself and everything I do, this helped not to take myself too seriously. And I’m not very fond of categories, I find words are terribly dangerous, as they seems to be as definitive as tombstones. This could maybe explain why my works are always “untitled”: it is like writing a joke on my own grave.

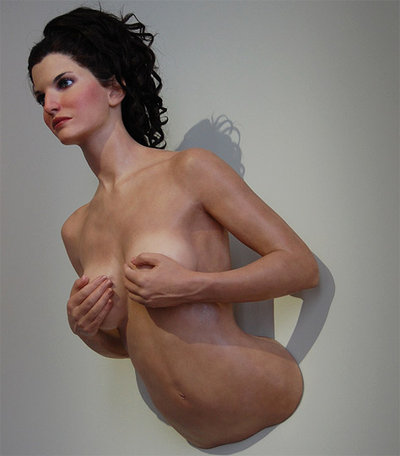

Elena Cué: Meaning and materialization are two fundamental criteria to define a work of art, the subsequent interpretation that each spectator brings to the work can be added as a third criteria (Arthur C. Danto). Given that the materialization of your work is carried out by others, in this case by Daniel Druet, a master in artisan modeling who has created many figures such as Pope John Paul II, Hitler, model Stephanie Seymour and Kennedy.

What importance do you give to the meaning and subsequent interpretation by the viewers?

Maurizio Cattelan: I never asked myself the question in this way, I just searched for images that, in the flood of useless information from which we are overwhelmed everyday, would stir an instictive reaction, from the stomach. Returning to the issue of humor, I think it can be a great way to bring to the surface anger, but without violence. Since the first moment of conception my sculptures were born as images and in that form they continue living in the media. As long as it is a powerful image at first glance, it’ll work.

Elena Cue: Your fondness for using images of iconic personalities holds huge power of communication. Pope John Paul II dying with a suffering expression after being struck by a meteorite in Nona Hora. The image of John Kennedy lying in a coffin with his bare feet in Now. Or Hitler in a smaller than natural size, kneeling in prayer in Him are, for better or worse, all examples of demystification to which you submit personalities who have been political or religious icons for masses of people. You appropriate their power and use it as a weapon at the service of your will.

What do you look for with such provocation and potential irritation that may result in a large proportion of viewers?

Maurizio Cattelan: To me it’s like when you are telling a joke, but no one would laugh: most of the times, provocation lies in the eye of the beholder. I believe there’s nothing wrong with showing people’s vulnerable side, moreover if they’re icons. It might help blur some lines but I don’t think it undermines their status. Quite the contrary, it reinforces their position as well as the belief that they are powerful or sacred icons.

Elena Cue: A very significant work is Bidibidobidiboo, in which your alter-ego is represented by an anxious squirrel in the kitchen where you spent your childhood. It commits suicide with a revolver dropped by its feet. The fact that the name of the exhibition comes from the magical words used by Cinderella to transform her miserable life into a fairy tale add an additional twist to an already surreal situation.

In Untitled 2004, you hung some children figures from a tree with a noose around their necks in Milan. The work lasted less than 24 hours because of the controversy and the anger it raised, which led to such high media coverage that it transformed the work into an iconic piece.

Do you use art as catharsis? Do you think that to affect emotionally, one has to surprise or shock?

Maurizio Cattelan: Someone once said that our heads are round so that our thoughts can fly in any direction: there’s no specific way of interpreting a work, its shape is round such as our heads. People can find a personal path, serious or funny, emotional or shocking, every way is walkable.

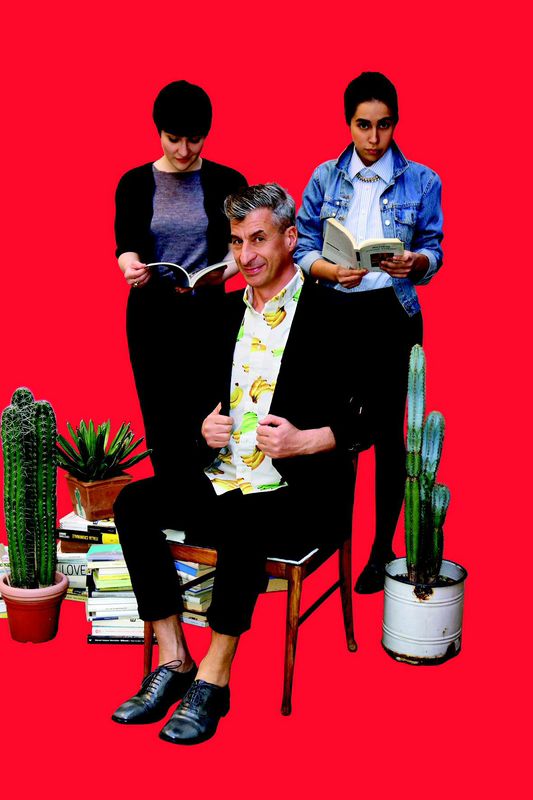

Elena Cué: Sarah Cosulich, the director of the Contemporary Art Fair Artisima has invited you to be a part of the 2014 edition of One Torino. The event will be held at the Palazzo Cavour, and it will open its doors on November the 6th. After abandoning your career as an artist, you will be in charge of commissioning this fair along with the two other young commissioners Marta Papini and Myiram Ben Salah. The name of the exhibition is Shit and Die and it is taken from the installation created in 1984 by Bruce Nauman: One Hundred Live and Die, that included multi-coloured neon phrases on 100 tragic and mundane possibilities to live and die. Shit and Die is one of them. This short declaration encompasses the existentialist worries of the author.

Could you elaborate on the meaning of this exhibition given its bleak name?

Maurizio Cattelan: We thought the combination of declarative ease and uncompromising toughness delves heavily into the universal human experience without imposing a neither fixed or stable meaning. Echoing the title, and echoing the path of life itself, the exhibition is a purposeless journey, simultaneously sad and hopeful, tough and absurd, silly and tragic, slight and profound. In the end, I would synthesize it like this: if you wake up and you’re not in pain, you know you’re dead.

Autorized translation of article, also published by the author in ABC

- Interview with Maurizio Cattelan by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -