Crossing the threshold into the London home of the musician, composer and visual artist José María Cano, one enters into a sensorial experience. I let the music floating from the second floor guide me to a room where his son Dani was immersed in playing the piano while José María sang Donizetti´s “Ah mes amis”. My presence in no way interrupted their symbiosis, and if anything I was lured into its flow. The scene brought me back to the heights of music José María had reached years ago with the band Mecano, and reminded me of the lyric drama of his opera Luna. Passing by the many works of art that scattered around his home, part of a magnificent collection he has put together over the years, we went into his studio, where surrounded by his own works —his La Tauromaquia and portraits, lining the floor and walls— the artist invited me to begin my interview.

Author: Elena Cué

José María Cano. Photo: Elena Cué

Crossing the threshold into the London home of the musician, composer and visual artist José María Cano, one enters into a sensorial experience. I let the music floating from the second floor guide me to a room where his son Dani was immersed in playing the piano while José María sang Donizetti´s “Ah mes amis”. My presence in no way interrupted their symbiosis, and if anything I was lured into its flow. The scene brought me back to the heights of music José María had reached years ago with the band Mecano, and reminded me of the lyric drama of his opera Luna.

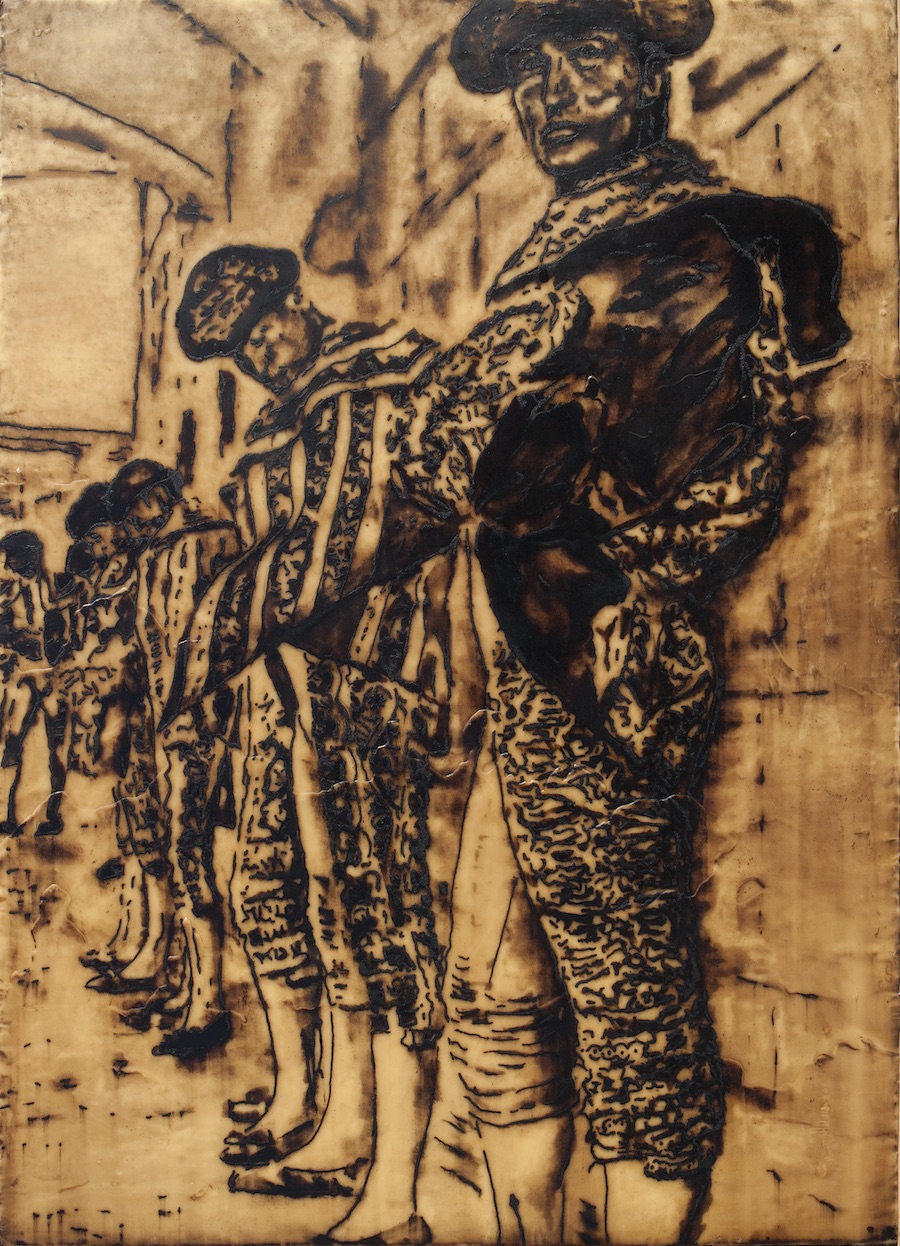

Passing by the many works of art that scattered around his home, part of a magnificent collection he has put together over the years, we went into his studio, where surrounded by his own works —his La Tauromaquia and portraits, lining the floor and walls— the artist invited me to begin my interview.

E.C.: You’ve just had an exhibition at the CAFA Art Museum in Beijing; 200 works gathered under the title Differences and Similarities between Reality and Truth. Tell me about that big show.

José María Cano: I was very pleased with it. Until then, museums had mainly exhibited my wax paintings concerned with economic issues, but that’s only half of my discourse. I felt that knowledge of my work had become lopsided; whereas this exhibition gave balance to its conceptual dichotomy. It’s not that my work has two distinct sides to it, but rather that I paint duality.

E.C.: Is that why you chose this title for the exhibition?

José María Cano: Yes, that’s right. The show was a retrospective of fifteen years of my work. The title, which some people find misleading, is actually the leitmotif of my painting. To my mind, the juxtaposition of the real and the truthful shapes is what carves us out as human beings. My paintings, which on the surface seem to offer a varied materialization, always walk that rickety line. Like when I was a kid. Climbing up to where nobody climbs, to see the world from there. Following the sun, and then the moon, and then the sun again, and only stopping if there was no moon. There’s nothing more seductive to me than the moon in summer or the sun in winter. With eyes opened or shut.

E.C.: Anyone listening to you would think that you live a very relaxed life, when clearly that’s not the case…

José María Cano: But they wouldn’t be completely wrong, in that I work by expression. More than work, I use the John and frame the result. Like Manzoni’s Artist’s shit cans. Even wax, which I like for my painting, is the excrement of bees.

E.C.: It’s true that you move between two almost opposite worlds. On the one hand, there are your paintings on your divorce papers, newspapers or the economy, and on the other, you paintings of a more spiritual nature, such as your series of apostles or paintings about the moon. “Between the sky and the ground,” as your song said.

José María Cano: This borderline way of seeing life lets me paint works from both banks of the same river. On one shore I get my clothes dirty and on the other I wash them. Human beings are a mix of matter and spirit which in the past were in constant, grueling struggle with each other. That battle drove and gave meaning to civilization. Read the poem by Lope de Vega “¿Qué tengo yo, que mi amistad procuras?” (“What have I that my friendship you should seek?”). We’ve now solved the problem by excising from ourselves the spiritual part. Living like that may be easier, but it ain’t worth a dime. Plus, it’s not impossible, with age and a little self-deprecation, to harmonize these two worlds within our selves. But works of art are forced to essentialize. I move steadily from the spiritual to the material, like a mason who stacks layers of brick and mortar, and then wipes away the excess with a trowel.

Wall Street 100 instalation. Beijing Museum. José María Cano.

E.C.: Do you think this view fits in to the current discourse of contemporary art?

José María Cano: No. Today’s art demands provocation, politics, total uniformity or hollowness for it to be of interest to its zoilists and many beneficiaries which, incidentally, include me. My painting lacks these four characteristics. So I won´t deny that my path is a solitary one. Luckily, my gallery is for snipers. Guess that’s why its name is Riflemaker.

E.C.: Your last exhibition was during the Frieze Art Fair Week. Why do you think that your gallery chose to show your work in such a desired week?

José María Cano: You’d have to ask them, but Tot Taylor has said that he values the technique and beauty of my work, and that it is atemporal and without shame. I’m glad that’s what he thinks, because he definitely doesn’t have any either.

Far side of the moon. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: I saw the catalog. You exhibited paintings of the moon…

José María Cano: Small encaustic paintings. I was told that it was the most talked-about exhibition in the press during Frieze. For instance, it was chosen as the show-of-the-week by the magazine The Week. The gallery had to extend its hours, and the works were acquired by museums and important private collections. This couldn´t have happened at other galleries, not with such subtle work. My moons were very happy there.

E.C. (reciting a verse from a song written by Cano and performed by Mecano) Hijo de la Luna... Parece que la luna le persiguiese donde quiera que vaya [Child of the Moon… It seems that the moon follows you wherever you go].

José María Cano: That song began with “a fool he who doesn’t understand”. From the ground, the moon is symbolic in character. There being two universes, this one is symbolic. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been fascinated by the works of Torres García. The moon is a clear indication of the visual dimension of the universe, and of the spiritual dimension of man. It is the recipient of humanity in its entirety’s most beautiful gazes, both living and dead. Sometimes we forget that most of humanity is dead, but it is; in the craters of the moon’s hidden face, perhaps.

E.C.: First a musician and then a painter, and successful as both. Which of these two arts do you think best transmits feelings and thought?

José María Cano: They’re complementary realms. I think that lyrics compel the listener towards a specific feeling. The visual arts are an open proposal to the observer. I like to listen, but I like to touch just as much, and especially to see. To touch things that attract my attention. And to observe them in detail. My paintings have an obscene tactility and I love it when people touch them.

E.C.: You use different media such as oil, resin, encaustic and pigments mixed with different binders. Why do you choose these materials over others?

José María Cano: I’m an alchemist in that “what I paint with” not only determines “how I paint” but also “what I paint” and consequently “what I feel”. The truth is that I paint with anything that lasts. The contrived search for originality is both the great discovery and the great evil of twentieth-century art. Fortunately, it seems like that whole antiquated debate, which is all it ended up being, is on its way out this century.

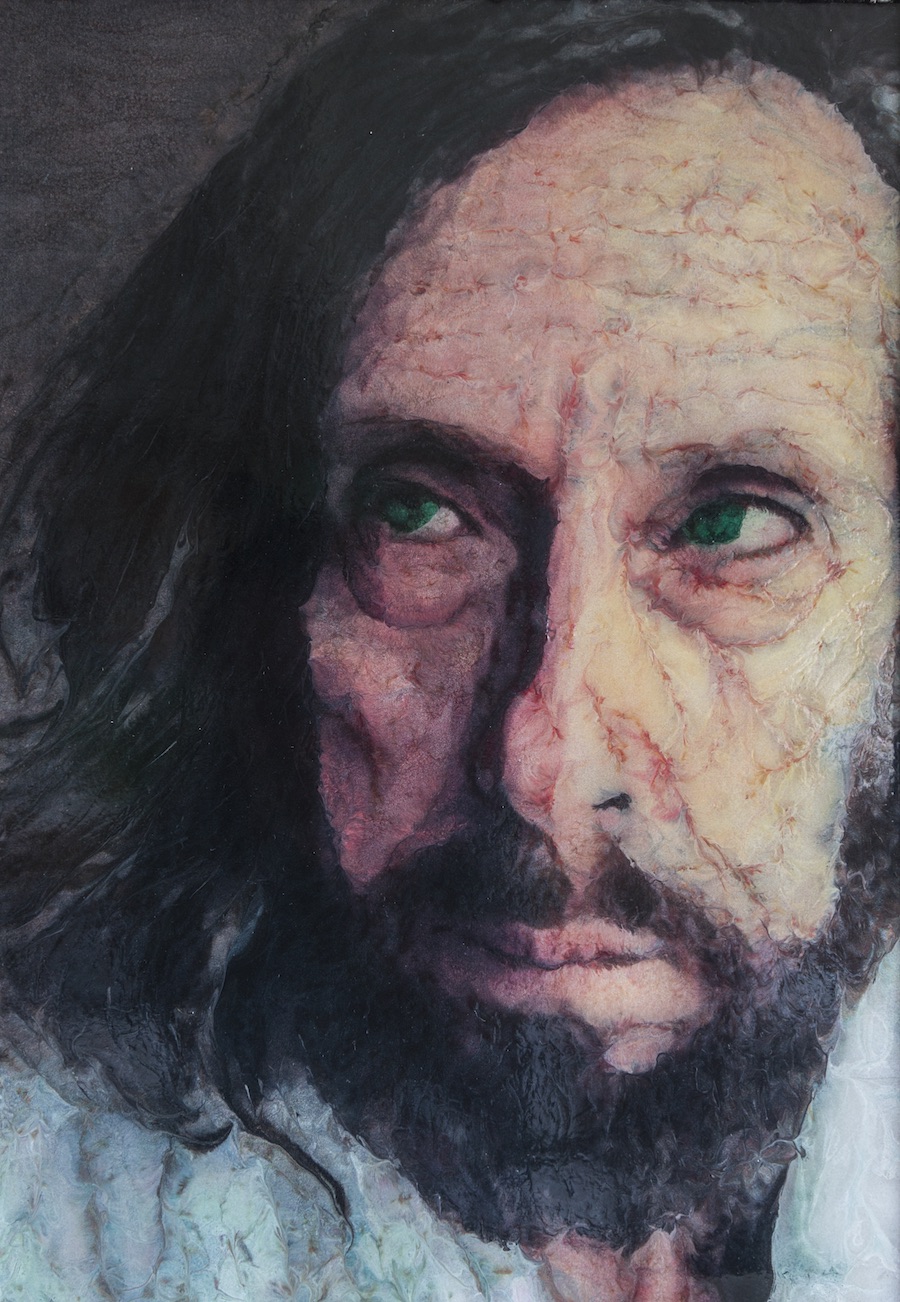

Saint James Bourneges. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: How did your years studying architecture influence your knack for drawing and painting?

José María Cano: More influential were my school years, prior to University. I went to a Jesuit school. Mr. Paz, the school’s photographer and drawing teacher, encouraged me to attend the Hidalgo de Caviedes academy. Up until then, I hadn´t ever seen a nude woman, not even in a photograph. I swear. And we were almost all guys. Once a week, a model would come and unfurl her anatomy. Very “neoclassical —but really, just plump. There were several of them, all well fed. It revved up our drawing. The reddish light of the furnace lent the scene a certain je-ne-sais-quoi. So, in this mix of hormones and graphite, I learned to draw, happy as a clam.

E.C.: Your close-up portraits strike me as very British, very School of London. Have you been influenced by your 25 years living in London?

José María Cano: I do see them as English, but going back further. To me, they are closer to Van Dyck than to Bacon, Auerbach or Freud. In fact, in their portraits, those painters showed a strong desire for originality that I don´t have. Quite the opposite. My portraits seek the timelessness of the upward gaze. Of spiritual questioning. Of physical peace. If there was something that I looked at as I worked on my apostles, it was the studies of male heads by Van Dyck, who lived in London but was Spanish, like me.

E.C.: You are very well versed in contemporary art and the social structure that supports it. What were your criteria in putting together your art collection?

José María Cano: I don´t consider myself an art collector. In fact, ever since I began painting professionally I stopped buying paintings by other artists. I like paintings as objects, and I like to live surrounded by them. But I don´t feel a sense of ownership towards them, nor much so for the works I paint.

E.C.: In your work, you focus on current affairs such as the defense of human rights, capitalism, prostitution... The titles of your shows at DOX Prague and PAN Naples were Welcome to capitalism and Arrivederci capitalism, respectively. Do you use your art as protest?

José María Cano: I’m not one to protest. Or complain. I began to paint as the leader of a movement with only follower —me— that I called materialismo matérico. That was the title of my exhibition at CAC Malaga. First I painted my divorce papers, and followed that with other works of a chrematistic nature. Figures of the financial world as they appeared in the Wall Street Journal, company financial statistics from the Financial Times, etc. But not as protest. I accepted these figures as the new beauty, ironically. And as an artist, as is customary, I felt compelled to pay tribute to such beauty by reproducing and magnifying it.

La Mirada. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: You’ve made a series of bulls, a very Spanish theme. How important are your roots to you?

José María Cano: My series of bulls is actually called De providentia and addresses the relationship of man to his destiny. It´s the title of a letter from Seneca to his disciple Julius, in response to his question of why bad things can happen to good people. Seneca answers that this only appears to happen. That water and oil don’t mix and that these challenges are opportunities for the brave man to demonstrate his greatness. In my ring, the bull represents mankind and the bullfighter, destiny. The right way to face destiny is not to hook into it and lift it off its feet. It’s to bravely charge right at it. And patience, of course, because the bad thing about providence is that it’s fricking slow.

José María Cano Apostolate Paintings of the Apostles San Diego Museum of Art with Spanish Golden Age

José María Cano. photo: Elena Cué