Berlin. On a sunny day, strong rays illuminate the studio where Thomas Struth (Geldern-Germany, 1954) meets with me to begin our conversation. This artist with an intense and precise gaze is one of the most interesting photographers of our time and belongs to the prestigious Dusseldorf Academy.

It appeared, I think, when I was almost 13 or so. Because it was not really a calling to want to be an artist, but I started to like drawing and using water colours and oil-chalk, and I painted my first oil paintings when I was 14. I had a room at my parents’ house, maybe 8 square metres or so, really a very small room. But I just liked to do that and I always loved music.

I started to learn the clarinet, then, when I was 14 my music teacher told me I should switch to saxophone and he started a school jazz band. So I played in the school jazz band for three or four years and then there was a time of pop music. Anyway I didn’t think about whether I wanted to be an artist or not, because that just wasn't the question. I didn't see myself becoming an artist, which I think was good because I didn't bother thinking about the future, I just did what I wanted to do at the time.

It’s important to note that you were the first artist to receive a grant to be in residence at the PS.1 Studios in Queens, where they dedicated an exhibition to you. Was this your first one?

Later on, you were a Professor of Photography at the University of Art and Design in Karlsruhe from 1993 to 1996, after already establishing yourself as a well-known artist. What was this teaching experience like?

I think I learned a lot about photography. He had developed an idea with new patients who came to look for help, where they'd tell a story and create a narrative about what they believed they suffered from and what they thought the cause might be. He asked them to bring 3 or 4 photographs to show what their family life was like. When we met and got to know each other, he found out that I was a photographer with a darkroom and the tools to print. So he told me that it was a dream of his for a long time to collect pictures like this and bring them together and work with them and make an exhibition at the institute where he was working. I said yes, I was interested, so we collected these photographs from about 35 people. Everyone brought about 2 or 3 photographs, so we had 80-100 pictures and I reproduced them all, made them all the same size and all in black and white, because before they were all in colour and I wanted to make them more comparable.

In the beginning, it was black and white because I couldn't afford to pay for the materials myself. I didn't have a colour printer. I didn't have the money for colour film, or the development. But the contact sheets and black and white were fairly inexpensive, so that had a very simple reason. Later I started to work in colour, but you don't look properly when you look at scenery in colour. When you photograph in black and white, you look at things in a different manner because you think more of cubic volume and light and shadow and stuff like that. You have to ignore the colours; you judge everything only by the density of light. Whereas with colour, of course you only look at the colour. You look at one scene and there's a bright red and then there's a bright yellow. You would find the attractive point in the picture where there's a dominant colour. When you have a blue sky and you photograph in black and white, the blue sky doesn't matter. If you have it in colour, the blue is dominant and it's an intense element in the photograph. Because when you look at it, the sky, it's air. But in the photograph it's a blue colour. It's blue paper. So it's a different thing. That's why, when I want to make a print now with the blue sky, my aim in the printing process is to make sure it looks like air. And not like blue paint. It's a very fine line.

Your photographs of urban landscapes in Unconscious Places seem rather objectified. Do they have any association with “Non-Places” by French Sociologist and Anthropologist, Marc Augé?

No that was not what I wanted to do. Everything is created by man. What I wanted to say with the title Unconscious Places is that when people design a building like this one or the curved one, the architect and the people who pay for it - or give the permission for it - believe it has to be contemporary. But beyond all this, it unconsciously creates an atmosphere that radiates to the people. I mean, the people who live over there in those buildings will look out at that building all the time when they look out of the windows. And the building is much uglier on that side there! So it's something that has a strong unconscious element, which matters a lot for the atmosphere for the city and the people who live in that building. Because the architect doesn't live in that building… They live somewhere else. Maybe in an old farmhouse, I don’t know, maybe in a pre-war building that is nicer. And maybe it has something to do with anger. So all cities are filled with this underlying unconscious, atmospheric energy. That was something I wanted to highlight.

The themes in your work could be like a socio-political analysis, because they reflect our current reality; family, technological and social structures...

I love to make pictures. I have to have a reason to make a picture. It's more fun to give myself a challenge in making a picture than to make pictures of the most obvious things. But I have to find excuses. There are all these questions about responsibility and society and questions about existence and the different levels of influences that exist. Picture making has a lot to do with that, to find reasons to make my pictures. But in principle, I have a strong urge to speak through pictures and not through talking.

Yes, you know some people speak through music, or architecture or sculpture or pottery… It’s a strategy to form an identity with the work you're doing. On the other hand, it's a problem to over-identify yourself with what you do. I think I'm a very invested artist, but sometimes I feel that I don't identify completely with the art world.

I think the conscious absence of people is necessary to show that what you're looking at is a human creation. And so the mentality and everything that humans represent is expressed through the buildings. With too many people it would just be a normal street scene, with people in houses and you wouldn't get that feeling.

During our discussion of how inspiration arises, I remembered your Paradise photographs, some of which were taken in Australia. Were you searching for inspiration there or did it come naturally?

I used to have an apartment in Düsseldorf for a long time with a terrace towards the back garden. I often used to have breakfast there, read the paper and observe the visual structure of the trees and branches, the information flow of these patterns. That stimulated the idea to make these kinds of pictures that would be very crowded with information which would make you surrender to the act of observation rather than interpretation. However, it could not be a German forest with pine trees and their dominating verticality. It needed to be something wilder, so I thought that jungle, primeaval forests would be good. I had a few trips scheduled, to Australia because I was invited to the Sydney biennale in 1998. In the North East of Australia, there's a jungle area that used to be connected with Indonesia. These two continents separated, so there's this jungle area north of Daintree. It's quite amazingand I came back with five pictures.

In any case, these days we're so used to taking so many photographs digitally.

Yes but I use a much bigger camera , so it is very complicated and it takes a lot of effort.

What is your concept of paradise?

Paradise is a condition of mind, soul, emotional quality I would think. I decided on this title to make sure people don’t think the work describes botanical differences etc.

It has different elements. You are confronted with yourself to a stronger degree. The constantly moving growth around you is very elemental. Nothing stays the same at all times, everything moves very slowly. As a friend of mine said, as soon as you stand still for a while insects and other animals appear, believing that you're something they could eat. So you're easily confronted with your anxieties. In that respect, there are confrontational elements. But the pictures are pictures, so what I think the pictures do is make the observer very calm. Because you can see it’s a jungle, so you don’t have to identify an assembly of objects: a carpet, a chair, a table, a woman, child, etc.. We cannot stop naming what we see. But when you look at the jungle photograph you don’t have to. You can refrain from this impulse.

You were the first photographer to exhibit at the Prado Museum. Could you tell me how you feel about that experience?

In my museum work, I wanted to connect with the paintings I chose in a particular way, through photographing groups of visitors corresponding with the figures in the paintings I photographed. It was maybe like an attempt of resurrection, to give people a hint that these master works or so-called master artworks were not created as such when they were made. They were made by artists in particular circumstances of their daily life and these works were not born as the famous artworks that they are now. I wanted to make them look like more contemporary works. The interesting question is: why do works of art speak to us? Why do we even want to look at them? Because they were made with condensed information about love and desire and beauty and all kinds of complex emotional qualities? Because of their artistic craftsmanship? What resonates in us during the observation, which is a playful process, and one thing that destroys play is too much respect. When you have too much respect you cannot play, you are intimidated, you become passive. I felt that people would go to museums with too much respect. They don't really know what they’re allowed to think. Maybe in the end they only go to those museum galleries because they know the artists or the specific paintings are famous. The peak of the phenomenon is the Mona Lisa and the way it's presented now at the Louvre, which is quite a carricature. I think what happened was that the artworks in my photographs became a little bit more contemporary and the visitors were pushed back into history, because once I've photographed them, the moment has of course already passed. It created this double reflection of consciousness.

I thought to do that would be amazing, so I decided to fly to Madrid and meet Miguel Zugaza. Then at the time, I had a fever and was not very well and I thought it was a bad sign, but anyway I went to the meeting and I was coughing all the time but we liked each other immediately. And then he said "I want to support you to do that". And that’s how it began… When I was about to start, he talked about inviting me to help open the new building and I thought that would be quite amazing. I showed these three friezes - one of the Hermitage in St Petersburg, one of the Accademia in Florence and one of the Prado. And then I thought I would have to convince the board, so I hired a video projector and made a PowerPoint presentation in the construction site. Then they started to talk about offering to show some of my works amongst the paintings, which I found extremely strange and I was not so sure if I could handle that or if that would be a bit too much. Because I think photography and painting don't go together so well. Photography and sculpture go well together but photography and painting don't.

Well, I do use minimally invasive digital corrections, but I’m not inventing anything. The digital process allows me to deal with partial contrast and colour changes or adjustments in a much more finely tuned way than in the darkroom. The more recent pictures are mainly photographs taken with large format and sheet film, scanned into a file and then we work from the file.

Can you reveal anything about your new project in Israel for the Marian Goodman Gallery in London?

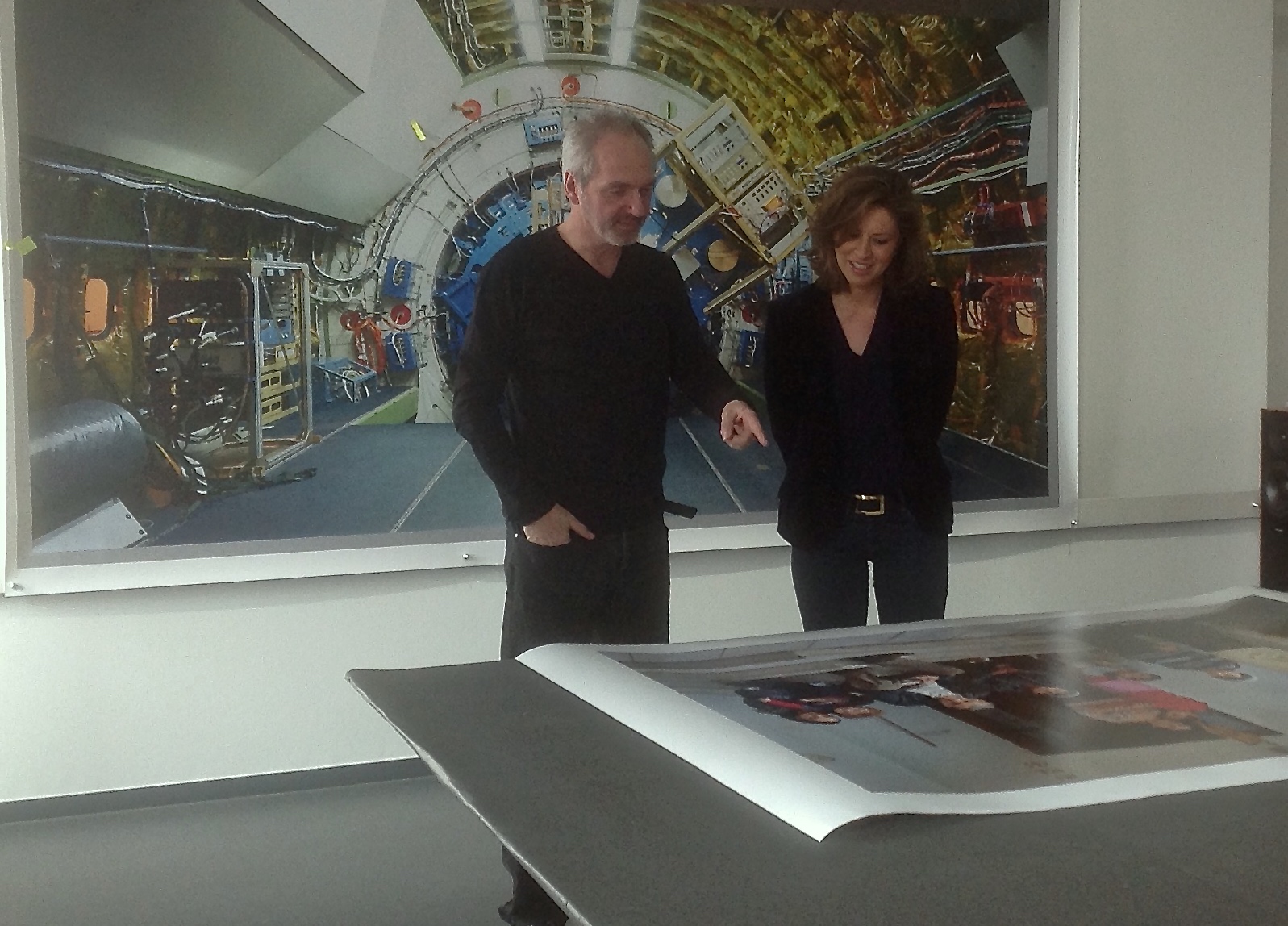

There will be some photographs that I made over the past five years in the context of this larger project called This Place. There are about 18 photographs in total but I will show maybe only 12 or so in London. Additionally, I will show new works I have made last year at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena and at the Armstrong Airforce Research Center near Edwards, north-east of Los Angeles.

- Interview with Thomas Struth - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -