At first glance, the work of Marina Abramović (Belgrade, 1946) would appear to conform to that hackneyed old saying that the best art is always about the self. However, as with so many other clichés about contemporary art, this serves only to limit the scope, richness and originality of this particular artist who, since day one over four decades ago, has made her own human body into a vital space for experimentation, her raw materials and a battlefield, even. Abramović herself is, effectively, the work itself. But only in as much as one must then incorporate this variable into a more complex equation, after pioneering reflection on the ultimate meaning of her performances which, after forty years of creative exploration, has consolidated her place and her identity within postmodern discourse.

Photo portrait of Marina Abramović by David Leyes

At first glance, the work of Marina Abramović (Belgrade, 1946) would appear to conform to that hackneyed old saying that the best art is always about the self. However, as with so many other clichés about contemporary art, this serves only to limit the scope, richness and originality of this particular artist who, since day one over four decades ago, has made her own human body into a vital space for experimentation, her raw materials and a battlefield, even.

Photo portrait of Marina Abramović. Image available at www.cronicasyversiones.com

Abramović herself is, effectively, the work itself. But only in as much as one must then incorporate this variable into a more complex equation, after pioneering reflection on the ultimate meaning of her performances which, after forty years of creative exploration, has consolidated her place and her identity within postmodern discourse. As a form of visual art, of art as action, her performances are both experiments in trying to identify and transgress limits of control over one's own body as well as, in regard to the relationship between public and performer, searching questions about the taxonomic boundaries in traditional art, based on the divide that exists between these two: subject and object. If we understand her body as simultaneously both subject and medium, Abramović's experimental probing breaks away from the ideas of stasis and temporality inherent in our usual aesthetic understanding, and thereby expands the dialogical, structural boundaries of any piece of art.

Still from A House with the Ocean View (2002). Image available at vimeo.com/72468884

The Serbian artist's performances involve an immediate and emotional exchange of energy with the public, as she intends, making them that last piece of the equation without which the transformative experience of art would be incomplete and in vain. On this matter, she has commented: "I could never give a private performance at home because I have no audience there [...] The bigger the audience, the better the performance and the more energy runs through the space. The audience should take an historic step and really connect with the object."

The artist is present (2010). Image available from the Marina Abramović Institute website: www.mai.art

From the very beginning, Abramović's output has been daring, provocative and transgressive. She began her artistic studies in the mid 60's in her birthplace of Belgrade, continued and finished them in Croatia, returning to teach Fine Art in Serbia in 1973. Ever since her debut with the well-known Rhythm (1973/74) series, framed as a bold, hazardous exploration of Body Art, the young Abramović was testing, on one hand, the body's limits in the face of physical pain, suffering, self-harm and, on the other, the moral resistance of the public to feel her world through those very personal experiences of her female body. It was a work in, on and of her body.

Rhythm 2 (1974). Image available at marinaabramovic.blogspot.com

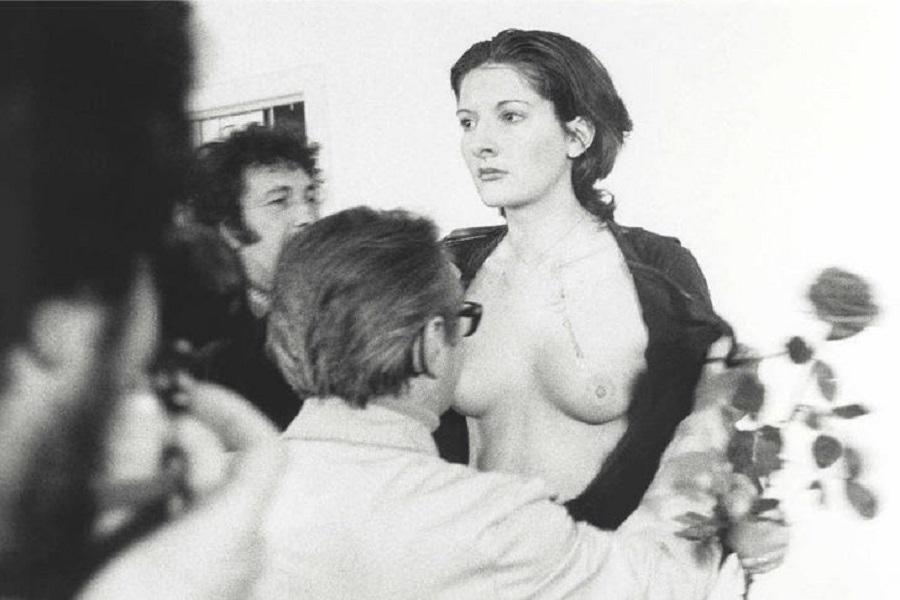

The different variations of Rhythm used embodiment to reflect on universal themes such as death, pain, sorrow, time, the limits of consciousness and unconsciousness, not to mention the behavioural patterns of the mind. Likewise, in Rhythm 2, she experimented with the varying states of lucidity and loss of corporal control produced by the ingestion of a range of different pills. In Rhythm 0, one of her most emblematic performances, Abramović literally put herself at the public's disposition. Along with 72 different instruments of different uses - from pencil to polaroid camera to perfume as well as knives, whips, chains and a loaded gun - she offered up her body for a no-holds-barred, unscripted, interactive show with her public.

Rythm 0. Image available at www.upsocl.com

The visitors were invited to choose any object and use it on her in whichever way seemed most interesting to them. And so began what was intended as a reflection on trust and the social contract and ended up being a palpable demonstration of Man's natural inclination towards violence. "What I learnt was that, if you allow the public to decide, they could kill you. I felt really attacked: they cut my clothes off, they scraped rose thorns across my stomach, one person held the gun to my head before another took it off him." Abramović's silence and lack of reaction meant that the violence escalated quickly and dramatically. "After exactly six hours, as planned I got up and started walking towards the public. They all scarpered, avoiding a real-life confrontation."

Rhythm 0 (1974). Image available at ourpursuitofart.blogspot.com

The subsequent evolution in Abramović's work owes much to her character trait of inclusivity and her willingness to be ever open to others. In a certain way, it's in her nature to have infinite possibilities. As opposed to the unitary and bourgeois concept of one single artistic identity, namely the definition of the artist-individual focused on each work as a solitary project, Abramović invariably challenges herself to build up emotional interactions with second parties and with herself as producer/director.

Proof of this came at the end of the 70's when her artistic output centred around an unclassifiable dual manifestation of her art in productive and emotional conjunction with her lover, the German artist and photographer Uwe Laysiepen, better known as Ulay. In a series entitled The Other, Abramović and Ulay performed numerous performance works as a duo in which their bodies – always synchronised, dressed (or undressed) identically and with similar behavioural patterns – created additional ways in which to interact with the public. Based on a professional and sentimental relationship of absolute trust, both liked to speak of an "adrogynous unity" whose actions personified the limits of interpersonal relationships, their effect on the "I", the ego and artistic personae. This is perfectly illustrated in Relation in Time (1977), one of their earliest joint perfomances, where this hermaphroditic union is symbolised by their tightly interwoven hair.

Relation in Time (1977). Image available at pomeranz-collection.com

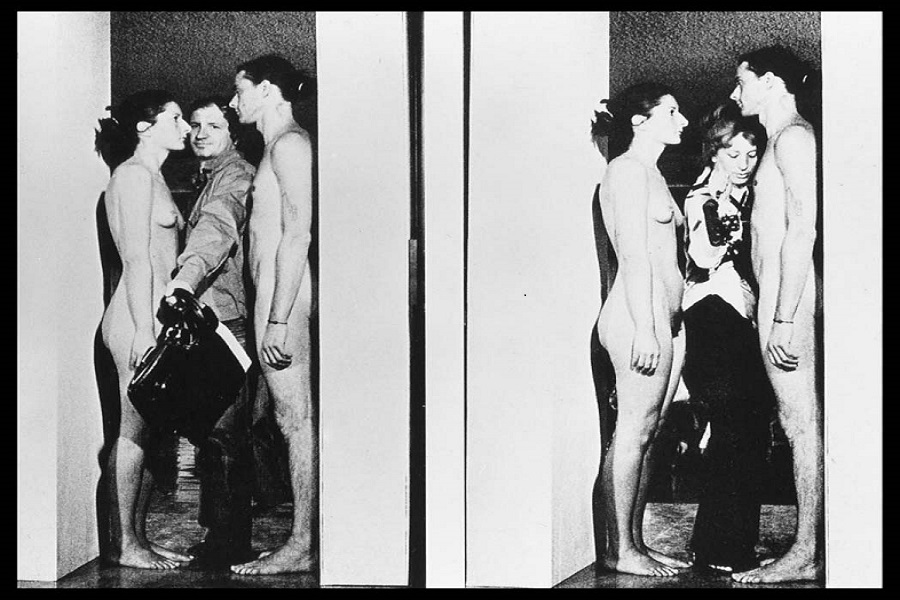

Their collaboration produced further and riskier (and indeed risqué) projects such as Imponderabilia (1977), where Abramović and Ulay stood facing each other, completely unclothed, in a narrow passageway at the entrance to the museum, thereby obliging visitors to squeeze between them and brush up against their naked bodies.

Imponderabilia (1977).Image available at delir-arte.blogspot.com

Another equally compelling joint performance was A-AAA (1978) where both artists shouted at each other in a firm-handed show of power designed to determine who had the more dominant voice. Better known is Rest Energy (1980) in which the couple faced each other, stock still for hours, holding a bow between them and the arrow between Ulay's fingers aimed directly at Abramović's heart. The strength and stamina required of both of them to maintain tension and prevent the arrow being shot was palpable. During the whole performance, microphones recorded both their heartbeats, both of them accelerated and agitated, a clear manifestation of a state of vulnerability in which responsibility and control could slip from their fingers any second.

Rest Energy (1980). Image available at www.altrevelocita.it

The "The Other" series, as much a passionate romance as an artistic collaboration, had as its symbolic finale the famous staging of 1988's The Lovers. Here too, their emotional and professional rupture was played out as a work of art, portayed as a hike, each on their own, departing from opposite ends of the Great Wall Of China until meeting up again in the middle. A three month long and lonely walk culminating in one last embrace. It is an almost definitive physical and communicational goodbye - it would be 23 years until they saw each other again - and an attempt to stage the disintegration of their relationship by means of the physical and emotional fatique occasioned by a 2,000 km journey on foot. It could in some ways be called a romantic ending: unclassifiable, unorthodox and emotionally charged with mysticism.

The Lovers (1988). Image available at http://inkultmagazine.com

With hindsight, Abramović's subsequent reinvention of herself as a solo artist could be defined as the crucial turning point in her career. A certain time lapse and, more importantly, long-distance travels abroad, Brasil for instance, led to a creative resurgence during the 90's that broke away, once and for all, from the conscious assumption that her life and her art would be inseparable from and fundamental to all her future productions. And so, although the body would continue to play an undeniable part, the performances evolved into spaces destined for the liberation of her own personal demons, underlying or otherwise, as well as new forms of performing as a way to explore how we relate to reality.

An illustrative example, from the early 90's, would be the object installations she herself defined under the umbrella term of Transitory Objects. By incorporating natural materials such as semi-precious stones, bones and magnets into her actions, Abramović wasn't looking to give them a function of their own, as if they were sculptures. Rather, she was using them to generate experiences and energies, as if they were everyday life rituals. One has only to remember, from the initial stages of this second phase 1990 - 1994, the Dragon Head series in which the artist sat stock still whilst various ravenous pythons, who hadn't eaten for two weeks, slithered all over her body. It's an image of potent mythic-feminine resonance.

Recreation: Dragon Head (2010). Image available at mai.art

Even more striking, given the eponymous violence of the time, was Balkan Baroque (1997) which won the Gold Lion award at the Venice Biennale that same year, the Festival's highest prize. Expanding on the theme of the human skeleton, previously explored in Cleaning the Mirror (1995), Abramović used video installation to recreate the putrifying horror of armed conflict in the Balkans War. As well as projecting an image of her own parents on the walls, the artist positioned herself in the middle of the space, washing a huge pile of 1500 raw, bloodied veal bones whilst singing traditional folk songs from her childhood. The dramatic staging no doubt owed a lot to the conceptual baroque of her design but also lent it sincere and credible political weight.

Balkan Baroque (1997). Image available at www.tropism.it

Abramović's recognition as an artist has been irrefutable since the turn of the century. Whilst, on the one hand, it is true that her active participation in various works has become so minimal as to be almost the mere fact of her being there, life and art for Abramović are intertwined as if an absolute presence, as if frozen in time. It is from this angle that she seeks to lift the public's spirit, not so much via direct emotional shock, performance surprise or Brechtian compromise but rather through other more energy-giving mechanisms such as silence, meditation and ecstasy-like consciousness: "To create a type of artwork that is almost devoid of content but still retains a kind of pure energy that will left the spectator's spirit", is how she described it in a 2008 Klaus Biesenbach interview.

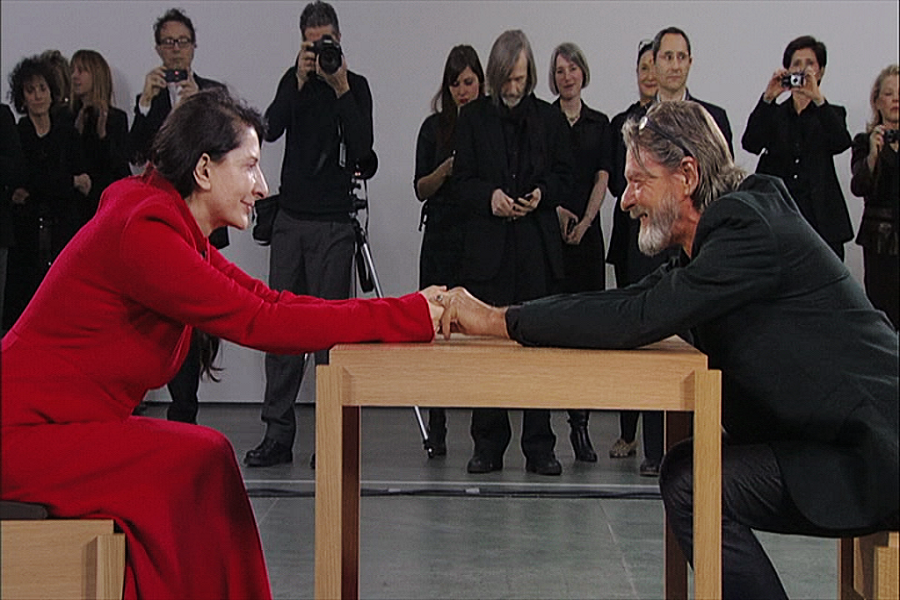

In this regard, one inevitably thinks of the unforgettable The artist is present, an exhausting performance piece presented in March 2010 on the occasion of a MoMa retrospective of her entire back catalogue which remains, to date, the most important ever and, with more than 50 exhibit pieces including performances, installations, videos, photographs and collaborations along with the subsequent documentary of the same name. For three whole months, Abramović remained seated in the lobby of the New York museum for over 700 hours (during opening hours and without a break) allowing over 1,800 visitors, each in turn, one by one, to sit opposite her in total silence, separtated by just a table, and to share the imperturbable presence of the artist for as long as they considered necessary.

The artist is present (2010). Image available at www.filmswelike.com

Like a challenge to time, like a reflection on modern-day society's emotional alienation, the hit piece created an immediate connection between artist and spectator - no verbal communication necessary - and made the lack of communication between one fragile body with another, especially in a great metropolis like New York, even more palpable.

There were also moments of utter surprise: after 23 years of separation, Ulay appeared out of the blue on the day of the inauguration. Abramović's heart visibly missed a beat on seeing him and he was the only one with whom she had any physical contact, after a brief conversation using only their eyes.

The artist is present (2010), reunion with Ulay. Image available at www.visualnews.com

But at the same time, it is no less true that diversification of format and method have been a constant in Marina Abramović's life and works, aware as she is of the increasingly global reach of what she has to offer and say. One need look no further than her much-lauded collaboration with Robert Wilson in the experimental opera The Life and Death of Marina Abramović which delved into the idea of her life's (and various deaths') leitmotifs as its narrative, with other great artists like Antony, Willem Dafoe and Wilson himself joing forces.

Marina Abramović and Antony in The Life and Death of Marina Abramović. Image available at www.robertwilson.com

As a final thought, one might ask oneself if, by focusing her most recent efforts on constant meta-reflection and revision of her prolific output, the potency of her artistic message has seen itself somewhat compromised by a worldwide success that has, unavoidably, transformed the scope, meaning and impact of her performances. Can those same concepts and themes of 20 or 30 years ago still be conveyed today? Given recent changes in the way artists communicate to us and the media and spaces now available to them, would it not be, rather, a case of qualitatively distinct experiences?

Slow-motion workshop, directed at the Whitworth Galley, Manchester (2009). Image available at passengerart.com

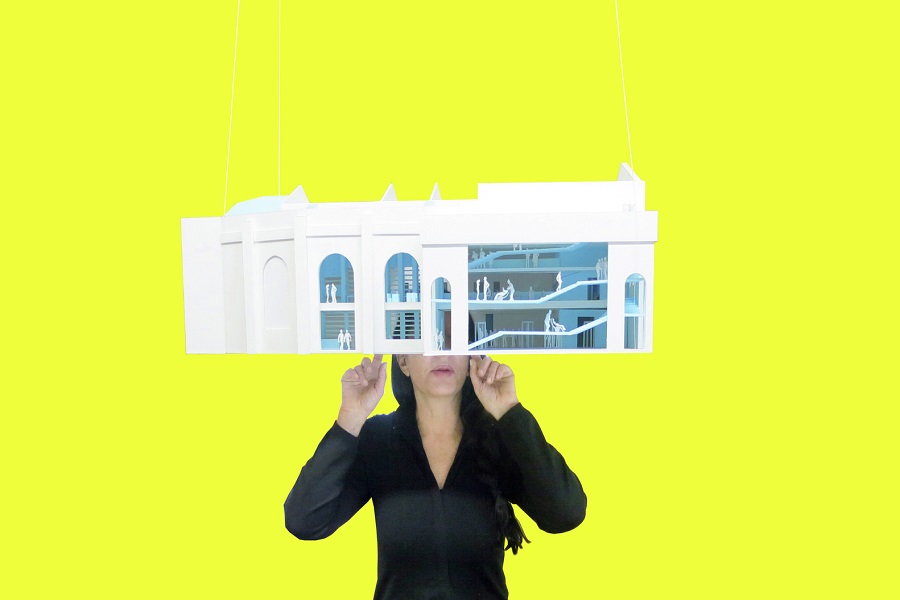

Art as action, live art made with the artists' own bodies is an artform belonging to a tradition predating but not predicting the digital age that came with all its short-lived sensations and hyperinformation. Neither did it anticipate a scenario of absolute trivialisation or the lionisation of those other anonymous performers of the 21st century, on youtube for instance. In any case, the conventional definition of performance as 'action that happens within a limited time frame' is in urgent need of revision. Perhaps the Marina Abramović Institue (MAI), inaugurated in 2015 in New York State, might take it upon itself to gather together a multidisciplinary think-tank to review it and instruct places of collaborative and experimental art in society today with the Serbian artist's legacy as a starting point. The "grandmother of perfomance", just turned 70, has a lot of life left in her yet.

Publicity campaign for the Marina Abramovic Institute. Image available at mai.art

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Marina Abramovic: Biography, works and exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -