2019: The Year of Rembrandt. Amsterdam kicks off Holland's 350th anniversary celebrations for the Old Master with its exhibition "All The Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum" which will then make its way to Madrid's Prado as "Vélazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer ~ Artistic Likenesses from the Spanish and Dutch schools". One would be forgiven for thinking the central gallery of the Rijksmuseum was less than sixty metres long because, on opening its panelled doors of leaded glass, our eyes are immediately drawn to the illuminated hand held out towards us by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. It beckons us from that distance away, making us want to step into the canvas with him as he gives the order for his company to begin their night watch through the streets of Amsterdam.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

2019: The Year of Rembrandt

Amsterdam kicks off Holland's 350th anniversary celebrations for the Old Master with its exhibition "All The Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum" which will then make its way to Madrid's Prado as "Vélazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer ~ Artistic Likenesses from the Spanish and Dutch schools".

One would be forgiven for thinking the central gallery of the Rijksmuseum was less than sixty metres long because, on opening its panelled doors of leaded glass, our eyes are immediately drawn to the illuminated hand held out towards us by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. It beckons us from that distance away, making us want to step into the canvas with him as he gives the order for his company to begin their night watch through the streets of Amsterdam.

The central gallery of this neo-Gothic museum somewhat resembles the stem of a basil plant, with its lateral chapels branching off either side of the central aisle and housing the world's largest collection of Dutch Golden Age paintings. The visitor is thus forced to zig-zag between them while, at the very end, in the apse, as if an alterpiece, hangs Rembrandt's "The Night Watch", his controversial, secular, colossal painting of 1642.

From the very start of this visit, we are already getting a sense of something quite different from the mythological, religious and military scenes usually found in other collections of 17th century Dutch, Spanish and Italian paintings. Where are the heavens opening to reveal the glory of God, the Depositions of Christ, the Flights from Egypt or the Epiphanies? Where are Apollo and Daphne, Danae, Proserpine?

Even before arriving at the Rembrandt gallery, several other pictures, oddly small in format, showcase another style of painting. Theirs saw the establishment of a brand-new genre of painting, one that is striking not just for its relentless verism but also for its never-before-seen themes. Domestic scenes portraying an urban, bourgeois life and families inside their homes of oak furnishings, Delft tiles and kitchens bathed in light. And their world of scenarios that are essentially feminine and intimate in nature ~ women standing alone, reading a letter or playing the harpsichord, cradling a baby, sweeping a room or putting on a pearl necklace, their faces lit by daylight from an open window. Scenes that almost seem to be happening on a lazy day off.

Vermeer, Woman Reading A Letter (1663-64), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Staggering numbers

There has been, perhaps, no other country ever where so many paintings have been produced in such a short period of time. It is estimated that between 1600 and 1700, up to 10 million paintings were produced in the Netherlands. Between 1650 and 1675, both Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) were active as well as at least half a dozen other top-notch painters such as Carel Fabritius, Gerard Dou, Gerard ter Borch, Frans Van Mieris, Jan Steen, Pieter de Hooch and Gabriël Metsu.

What made such prolific artistic production possible? What led the United Provinces to write a fundamental chapter in the history of art? An art which, incidentally, was at once so very localised yet so eternal?

From a technical point of view, the theorist Karel van Mander, echoing Giorgio Vasari, confirms that Golden Age Dutch painting derived from 15th century Flemish painting, from the preciosity of Jan van Eyck's, Robert Campin's and Roger van der Weyden's paintings, still under the guise of religious scenes but also depicting the interior of contemporary homes, their fireplaces, chancellors' bibles, saints' clogs, the damask and fur of their garments and the lilies of archangels.

The artists' lives were, coincidentally, punctuated by highly dramatic, military and political events that did not, however, seem to have left any mark on their work. The 17th century was one of the bloodiest in history, its wars notorious for their long duration. The Netherlands, divided by Civil War into Calvinists and Catholics, fought the Spanish Crown in the same way it fought the sea which inundated its plains time and time again, filling its landscapes with windmills, dykes, canals and bridges. They were Master Naval engineers whose fleets managed to achieve dominance over most of the world's commerce. Until the 1640's, the Dutch empire extended from Brazil to Africa and from Indonesia or Japan to the east coast of North America, establishing its capital there as New Amsterdam, now known as Manhattan.

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded, its 160 ships sailing the oceans transporting and unloading extraordinary cargo ~ tonnes of blue and white Chinese porcelain, wood and grain from the Baltics, Persian rugs, sugar from Brazil, fruit from the West Indies, spices and pepper from Java, Sumatra and Borneo. Turkish sultans sent tulips and with them came 'tulipmania' which, in the 1620's, almost caused riots due to a price rise. A few absurd sales receipts still exist ~ luxury mansions paid out in exchange for a single bulb. It was the first speculation bubble in history.

Amsterdam and its port thus became the greatest trade centre in the north of Europe. A Stock Exchange was established there and is considered, after that of Antwerp in 1460, the oldest in the world. Founded in 1602 by the VOC, and the first to function like the modern stock market, its aim was to create funding for future commercial shipping.

This global trade network created an elite clientele with abundant amounts of money with which to adorn their houses. The decorative arts flourished, as did the quest for luxury items and, above all, paintings which were to become the new status symbols. Gone the patronage of aristocracy and Church, it would be the bourgeoisie from now on paying the piper and calling the tune on the subject matter to be painted. And they wanted to see a reflection of their own lives, their hardships and dreams in those paintings. They wanted to feel recognised. Dutch art, artists, buyers and dealers were the catalyst for the future international art market, such as we know it today.

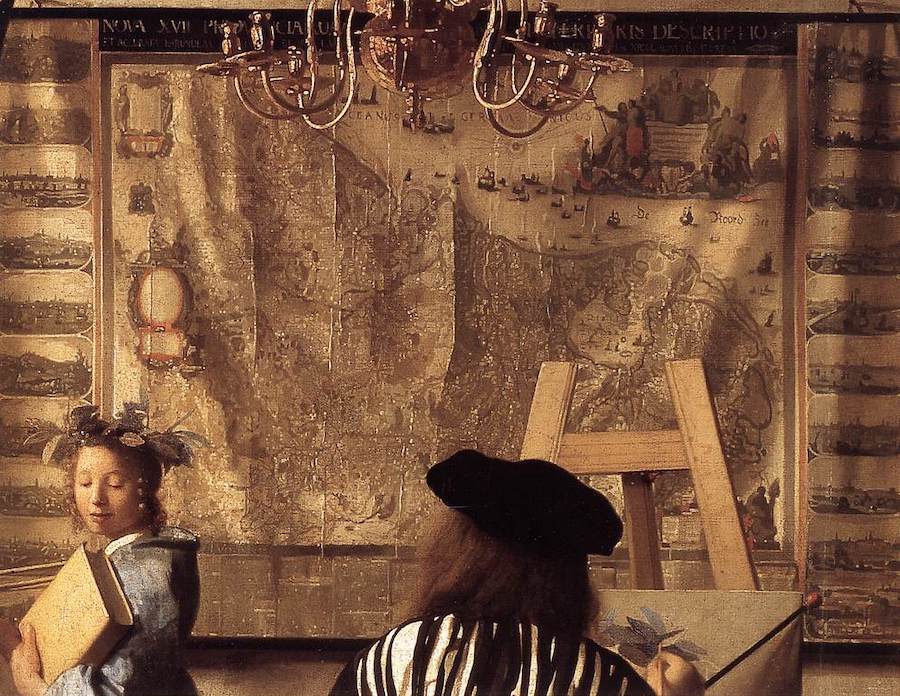

Vermeer, The Art Of Painting (1666), detail showing a map of the United Provinces, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Leapfrogs and bounds

This is script being written and informing our progress through the galleries, providing context and background against which Vermeer in Delft and Rembrandt in Amsterdam showcase their own particular way of painting. In the case of Vermeer, it would appear to be a natural progression from the mentality of his time. For Rembrandt, it was a giant leap forward.

On a wall near "The Night Watch" hang three tiny paintings that signal, from the outset, an ethereal calm in space and time. These are all three Vermeer paintings owned by the Rijksmuseum. "The Little Street" (1658) measures little more than fifty centimetres and is so lifelike it appears not to exist at all. It is as if there were a hole in the museum wall through which a real street scene in Delft can be glimpsed. Perhaps for this reason, it is said of Vermeer's art that it predates the realism of photography, the only artform to, centuries later, attempt to portray the very air surrounding figures in this way.

Vermeer, The Little Street (1658), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"The Milkmaid" (1659) is dressed in Vermeer's favourite colours of yellow and ultramarine, intently pouring a fine stream of milk into a clay bowl. She looks as if she is not to be disturbed. The still life on the table with its crusty bread and specks of sunlight, the wicker basket and, most noticeably, the wall behind her bathed in light creating a shadow under the nail, the different colourations of whites marking a stain or, as in the corner, the ochre variations of damp combine to form an intense reality, small but perfectly-formed, vast and magical. The precision of tone is remarkable. An artist must, in short, have the gift of seeing everyday things in a different way to us. Creativity has to entail something like how to illuminate these ordinary things with a brighter light, with more concentrated attention, with a distinctly powerful charge. When Rembrandt paints a glass of wine, it ceases to retain its natural state of being a glass of wine and becomes, rather, part of an action. He beams theatrical light onto it, he sets it on a stage. Vermeer, on the other hand, isolates it, wanting a light just for this one glass, he grants it the virtue of being itself, unique, material and independent, in a moment of time that is motionless. Vermeer paints the time that flies between things.

Vermeer, The Milkmaid (1659), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the years when Rembrandt and Vermeer were active, the world was engaged in a scientific revolution. New ideas were being touted about what it meant to 'see'. People had started to believe Nature was hiding a world invisible to the naked eye and that science should focus on researching it and finding out. There was a wave of empirical thought needing to back itself up with instruments able to measure Nature and allow us to see parts of the world that had been hitherto invisible. Hence, the 17th century saw the invention of the thermometer, the barometer, the telescope and the microscope. And its painters, determined to discover Nature and to paint it using an array of optical effects, went back to relying heavily on lenses and camara obscura devices. We do not know whether Vermeer used such techniques in his painting or not but what is certain is that he was familiar with the effects they produced and how light influenced how we see the world. He reproduced how it accentuates colour tonalities until they appear jewel-like, how it blurs or sharpens the outlines of figures, how it highlights where the touches of light brighten and polish whichever reflective surface the sun falls on.

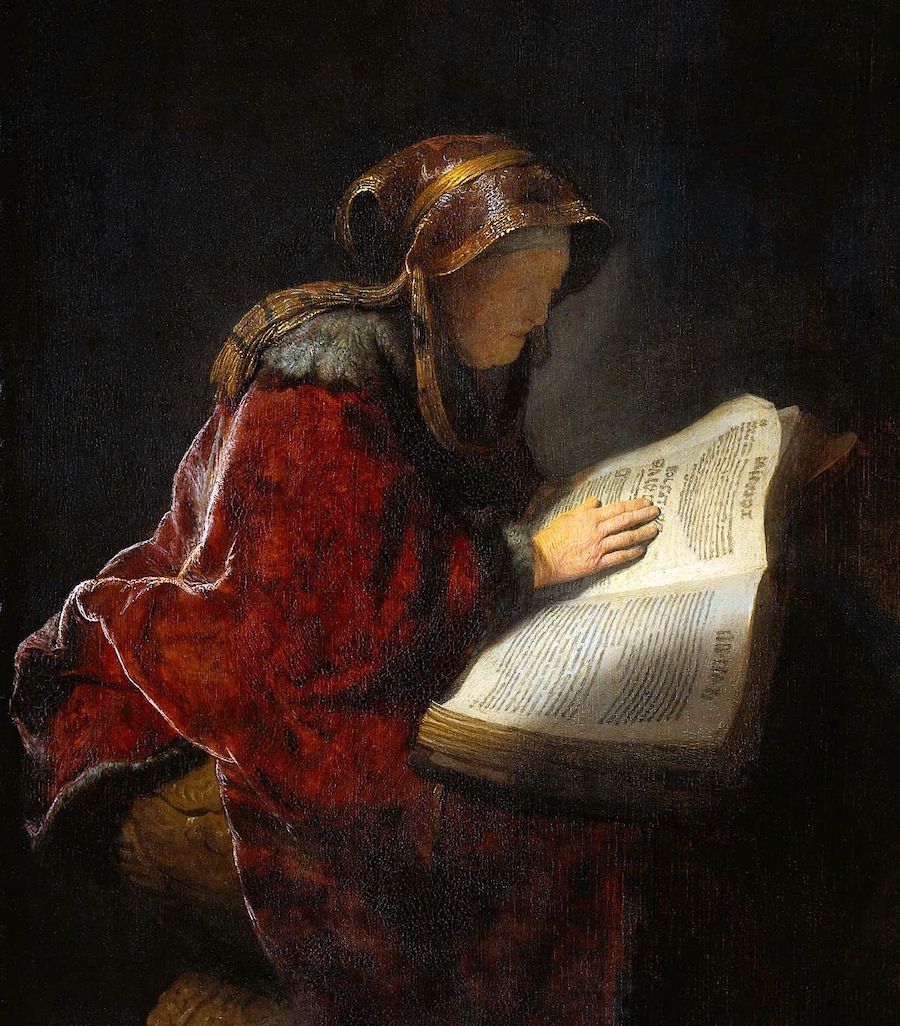

Vermeer painted "The Milkmaid" some 16 years after Rembrandt started work on "The Night Watch". Both paintings were a pictorial revolution but they were poles apart. To simplify Svetlana Alpers' study of 17th century Dutch painting, one might say that Vermeer represents the pinnacle of descriptive painting and its debt to observation whilst Rembrandt uses narration and historical themes as a pretext for injecting a certain wildness into his painting as the key to expression, action, gesture and the innermost recesses of the soul. His studies of light and matter are merely a means by which to paint the depths of pain, loneliness, failure, power, blindness or life just before death.

Rembrandt, The Prophetess Anna (Rembrandt's Mother) (1631), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Ten years, ten days

In a documentary about the last years of Rembrandt's life, Simon Schama describes a scene. It is 1885 and a young artist visiting the Rijksmuseum stops dead before a painting, his eyes transfixed, breaking into a feverish sweat as he gazes at the adored work. "I would give ten years of my life if I could simply sit and meditate, with a dry crust of bread, for ten days looking at it." So what was it about "The Jewish Bride" that so mesmerised the young Van Gogh? Days later, he would write that Rembrandt had painted it with "a hand of fire". Schama interprets the impact on Van Gogh as that of any masterpiece ~ it takes aim directly and viscerally. Van Gogh was another painter who took brushstrokes to their most physical extreme and this final work of Rembrandt's left him spellbound. In it, the Old Master, by now penniless and at death's door, depicts the physical incarnation of love. Its whole meaning is that of touch and caress. "The Jewish Bride" is a symphony of four hands, those of a couple. A man's hand on his wife's heart, the woman's hand touching this hand, a man's hand protectively around his wife's shoulder ...

Rembrandt rushes this final painting with the rage of his materials. The sleeve he paints here is not easily explained and one would need to be standing, as Van Gogh did, right in front of it. The sleeve is a physical crust in dozens of shades of gold, a mass of pictorial density that has a whole world of matter embedded in it: pieces of egg shell, crushed glass, mud, silica, ... The Old Master is acting on the painting the way the likes of Pollock, Freud and Kiefer would act on theirs centuries later ~ painting emotions with their materials.

Rembrandt, The Jewish Bride (1662), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"The Jewish Bride" features in the exhibition, as does "The Night Watch" with its outstretched hand, along with the whole astounding collection - the world's largest - of Rembrandt's canvases, drawings and etchings owned by the museum. Nevertheless, what makes this exhibit unique is something else. It is, essentially, about finding oneself in the presence, just a few feet apart, of two genius but contrasting artists. In and out of Rembrandt, on to Vermeer, retrace our steps back to Rembrandt and ..... start all over again. As Simon Schama said about them: Vermeer versus Rembrandt ~ crystallization versus emotion.

Rembrandt, The Night Watch (1642), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

All the Rembrandts at the Rijksmuseum

Rijksmuseum

1070 DN Amsterdam

Curator: Jonathan Bikker

15 February ~ 10 June 2019

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)