This could be the beginning of a novel: Poseidonia, 5th century BC, and tragedy befalls a family from the local aristocracy. The lifeless body of their only child, a son initiated into Orphic rites, is returned to them from the Wars of Sybaris. The mother covers her son's eyes with Poseidonia's first roses in flower, their praises sung by Virgil for their perfume and twice-yearly blooms. The mother then lays her musician son's lyre, its soundbox a turtle shell, on his breast. As dawn breaks, the father leaves the city walls to commission the most opulent of burials for his son. He seeks out the most gifted painters, those able to create the most moving scenes ..... This article pertains to the story of a burial: an element as intrinsic to the human condition as our own mortality.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

2018 marked the fiftieth anniversary since the discovery of the enigmatic Tomb of the Diver. Now on display at the Museum of Paestum in Campania, its 37-year-old archaeologist director Gabriel Zuchtriegel - yet another German director of an Italian museum - curates the Autumn exhibitions celebrating this ephemeris.

*******

This could be the beginning of a novel: Poseidonia, 5th century BC, and tragedy befalls a family from the local aristocracy. The lifeless body of their only child, a son initiated into Orphic rites, is returned to them from the Wars of Sybaris. The mother covers her son's eyes with Poseidonia's first roses in flower, their praises sung by Virgil for their perfume and twice-yearly blooms. The mother then lays her musician son's lyre, its soundbox a turtle shell, on his breast. As dawn breaks, the father leaves the city walls to commission the most opulent of burials for his son. He seeks out the most gifted painters, those able to create the most moving scenes ..... This article pertains to the story of a burial: an element as intrinsic to the human condition as our own mortality.

A tomb was - then and possibly still now - a sacred place where, as believed among initiates in the Orphic mysteries, the transmutation of death into resurrection, the moment when the soul was liberated from the body, took place. And for that to occur, a perfect setting was required. This is why Egyptian tombs concentrated all their magnificence and all their condensed artistry on the inside. This is why perfection was sealed up and hidden away. And this was because there was a mystery contained within them.

In Ancient Greece, as a partaker in the mystery religions rather than in terms of its Olympian beliefs, the tomb also became a sacred place. They were a kind of magnificent time capsule, decorated almost to perfection, a little chamber that led to another state of being.

On 13th June 1968, the Italian archaeologist Mario Napoli is carrying out excavations at a small necropolis about a mile south of the city of Paestum - the Ancient Greek city of Poseidonia - on the Gulf of Salerno in Southern Italy. As evening falls, he starts work on a fourth tomb that, when finally dug free from the earth, looks surprisingly intact. With the sun setting, the box is opened and, after 2,500 years of darkness, light floods the interior of the tomb once more, bringing some astounding paintings back to life.

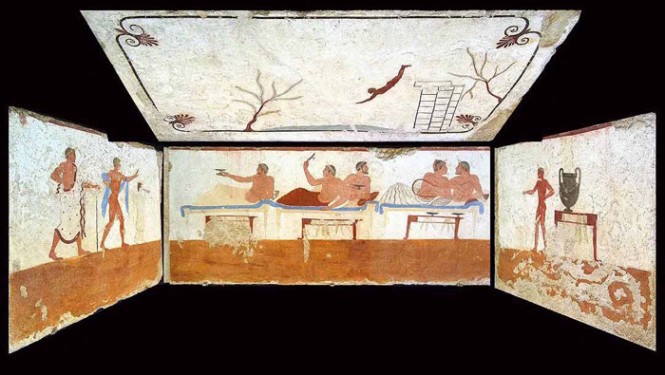

Slabs from The Tomb of the Diver, in their original positions

The four sides and cover of the sepulchre consist of five slabs of local limestone, while the base is dug into the ground. The slabs are neatly bonded together and form a chamber about the size of an adult male. All of the slabs are painted using the 'true fresco' technique but the fact that the one forming the ceiling is also painted is somewhat unusual. Mario Napoli sees for the first time the scene that will ultimately give the tomb its name: a young man diving towards the curling waves in the waters below. The Tomb of the Diver has just been discovered, the only extant example of Greek painting with figurative scenes from the Orientalizing, Archaic or Classical periods to survive wholly intact. Among the thousands of Greek tombs known of at this time (700 - 400 BC), this is the only one decorated with frescoes depicting humans. It is, in this sense, a revolutionary one. The great paintings of Zeuxis, Apelles and Parrhasius have only come to us through narrative tradition and historians but we have never seen them. They exist only in fragmentary form and, of course, in the richness of the amphorae.

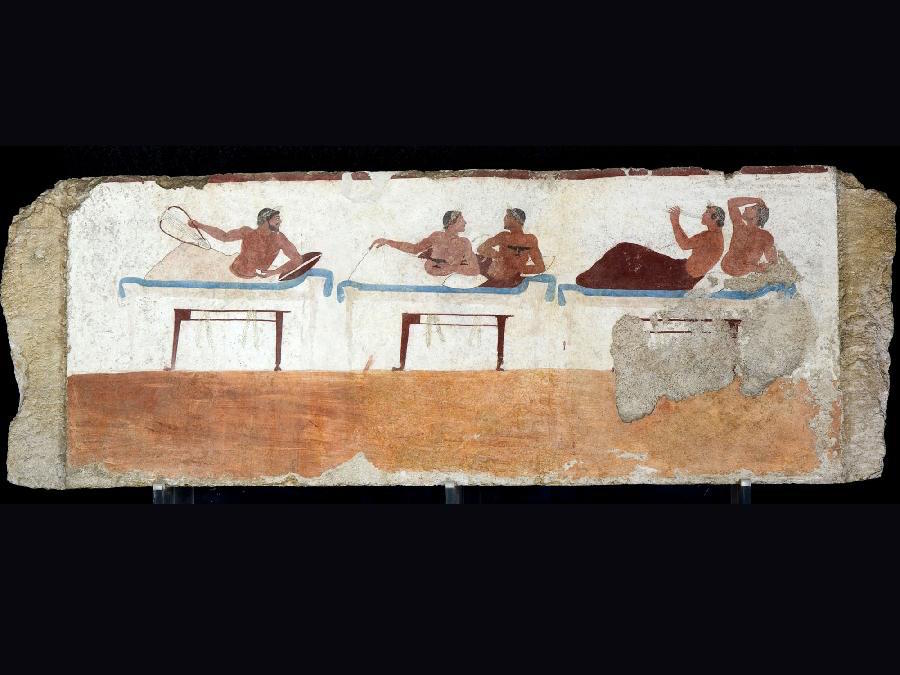

Inside the grave and near the body - probably that of a young man - are two objects: the shell of a turtle, once the soundboard of a lyre whose wooden casing had long since rotted away and an Attic lekythos vase in black-figure technique, as used around 480 BC, which helped to date the year of the tomb to around 470 BC. The lateral frescos surrounding the body depict symposium scenes of a traditional Ancient Greek banquet: bare-chested young men wearing laurel garlands reclining on sofas, partying, dancing, drinking wine, playing lyres and games and being in love.

The Tomb of the Diver. North Wall (banquet scene detail)

However, it is the ceiling slab, the one facing the gaze of the dead man, that has been the still-unresolved focus of much contentious interpretation. It is this segment that encapsulates the mystery and the rivers of ink written in archaeological research: a scene bordered by a black ribbon with palmettes in each of its four corners. In the centre, a naked man suspended in the air, diving into the river below. On the right are three stone pillars, presumably his diving board, and on either side are the bare outlines of two trees. And then, nothing. Just the white background, nothing else.

The Tomb of the Diver. Ceiling slab.

In Ancient Greece, neither swimming nor diving were activities the elite indulged in. The swimmer depicted in this tomb, isolated against the sky, symbolizes - the jury is still out on all the hypotheses - the intensity of the moment of death. This man and his leap are the visual metaphor for the transition to eternity from earthly life.

At that time, Greece was living the tradition of its Olympian beliefs, with its bored, mountain-dwelling gods, impervious to earthly needs toying with, for pure entertainment, and torturing mere mortals. For them, the vision of life after death was extremely pessimistic. Without exception, without differentiation, without judgement on the righteousness of their previous life, the souls of all mortals were condemned to Hades, a dismal place where they eked out a miserable existence envying the living.

However, around the time The Tomb of the Diver was constructed, for those living in Magna Graecian cities, new ideas from other Eastern belief systems would come and go in their everyday lives as if by capillary action: the mystic or Orphic cults, for instance, whose occult rites were based on the hope for some kind of life after death. As Pythagoreanism and Orphism spread, only those who had been initiated through a series of secret rituals could aspire to these other-worldly hopes.

And it is precisely this aspect that makes our tomb so special: the metaphysical message it communicates through visual language. Because it is the case of The Tomb of the Diver that the paintings seem to be portraying the central ritual of initiatic, religious practices entailing a banquet in which, through orgiastic stimuli, a state of exaltation and mystical fervour is invoked in the participants. This state recalls the passion of the God Dionysus and his presence inside an animal that was ripped to shreds, its flesh and blood consumed by Titans in a ceremonial banquet. The intense fervency attained enabled participants to feel the force of the soul within the body and this anticipated the experiencing of its liberation from the body which could only happen after death, once the soul had finally departed the body.

Incidentally, this idea of life after death was being propagated in Greece a full five centuries before the birth of Jesus Christ in Bethlehem, Judea. We have here an early precedent for Christianity that would seem to be its replica projected backwards.

It is believed that our young man, who died long before his time, would have been an initiate of these rites. In his tomb, the image of death as a rapid passage through water would remain forever above him. And his body would be surrounded by scenes from a banquet that would never end and in which he would participate for all eternity, playing his lyre with his musician friends.

But who was the young man buried there? What kind of life had he led? How did his parents commission his tomb? What of the two artists who painted it? What did they do with their son's body on the days when the tomb's walls were being cut out of rock, plastered, dried out, chiselled to outline the drawings and then filled in with vivid colours? And again, why paint a magnificent tomb to be seen at the precise moment of burial only to seal it up immediately, never to be seen again?

An invisible image

An invisible image is a challenge. What happens when an image, painted 2,500 years ago never to be seen again, bursts onto our contemporary, traditional, cultural landscape where being comprehensible is the equivalent of being visible?

One thinks of other images in art history with encrypted messages, from Malevich's Black Square or the mysterious Romanesque frescos of San Baudelio de Berlanga to the prehistoric Altamira Cave bison and the inscriptions on the earliest Christian catacombs and Banksy.

Perhaps what's puzzling about The Tomb of the Diver is not so much the impossibility of deciphering its meaning but rather our attempts at coming to terms with the powerfulness of an image's intrinsic ambiguity.

The temples of Paestum and The Tomb of the Diver

On this October day, the grassy area surrounding the temples of Paestum is empty of visitors and full of autumn roses. The three Doric temples appear erect and severe in their golden Campania stone, about 90 kms from Naples and the shade of Vesuvius. The Temple of Neptune (460 BC), thus called but wrongly attributed to Poseidonia's protective divinity, is, for many scholars, the best preserved temple in Greek civilization. It is not easy to describe the powerful impact of seeing its facade, devoid of any decoration whatsoever, not even holes in the stone that might have allowed us to imagine there once being a statue clamped into its tympanum, nothing resembling the Pantheon or Phidias's statues of gods, horses, warriors, ..... This temple was conceived of to be bare and stern, even in its triglyphs and the metopes between. No goddesses on horseback. The tension is achieved solely by its monumentality, by the magic of its proportions, by its second row of intact columns, with its fluted pillars high as a forest and its orientation towards the East.

The Temple of Neptune. Paestum

In the 8th century BC, the Greeks were sailing the Tyrrhenean Sea around the mining regions of the Etrurian coast to buy metal. They settled near Ischia and so began their campaign of colonisation. Around 600 BC, sailors from the city of Sibaris founded the colony of Poseidonia, making it one of the northernmost extremes of Magna Graecia. It was then conquered by the Lucanians and finally, in 273 BC, fell under Roman rule and was renamed Paestum. The discovery of Paestum came in 1752 when King Charles VII (the future Charles III of Spain) ordered the construction of a road which would cut across the city. From then on, European intellectuals doing the Grand Tour, amazed by how well-preserved the temples were, made it their reference point for classical architecture until Athens was added to the European cultural itinerary. It was specifically in Paestum that Greek architecture achieved supremacy over the Roman and where the Greeks regained their "tyranny" over Europeans enamoured with their monuments. Winckelmann (1758), Piranesi (1777), Goethe (1787), John Soane (1779) and almost all the great architects of the time came here to see, study and measure the purest of all Doric temples. In 1758, the architect commissioned to build the Pantheon in Paris, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, found inspiration in the temples of Paestum, making the Neoclassical style so popular in France it would end up replacing the Barroque.

National Archeological Museum of Paestum

Vía Magna Graecia, 918

Paestum

Italy

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Una imagen invisible: la tumba del nadador - - Alejandra de Argos -