This exhibition bombards us with a storm of ideas. It is a gauntlet thrown down to us by the Royal Academy and one that Gormley takes up, with all his weapons and from all sides: with lead, steel, seawater, a little blood from his veins and a battalion of iron men, dozens of soldier Gormleys. It has been four years in the making during which time, for the positioning of each and every piece, every conceivable permutation has been tried. Also during that time, the building’s architecture has been subjected to extremes, pushing it to its very limits: walls supporting massive weights, average-sized rooms housing pieces the size of something from another world, from Gulliver’s Travels, that balloon out against the doors, against the corners, while, in the adjoining room, the floor has been turned into a pond and is flooded with water.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Subject (2018), Royal Academy of Arts, London

This exhibition bombards us with a storm of ideas. It is a gauntlet thrown down to us by the Royal Academy and one that Gormley takes up, with all his weapons and from all sides: with lead, steel, seawater, a little blood from his veins and a battalion of iron men, dozens of soldier Gormleys. It has been four years in the making during which time, for the positioning of each and every piece, every conceivable permutation has been tried. Also during that time, the building’s architecture has been subjected to extremes, pushing it to its very limits: walls supporting massive weights, average-sized rooms housing pieces the size of something from another world, from Gulliver’s Travels, that balloon out against the doors, against the corners, while, in the adjoining room, the floor has been turned into a pond and is flooded with water.

However, here in this tension is where, constant and dense as a thread of light, Gormley's discourse lies. In that sense, this doesn’t seem like a conventional retrospective but a statement of the principles of the artist who, from the start, has persevered in the continuity of his incessant, unsettling question, like a gong, like a boot kicking metal and in his obsession with getting us involved, shaking us up, waking us up: "The body is more a place than an object for me: body "in" space and body "as" space. Come with me, close your eyes, look inside your body, into that darkness where the limits of space are lost, where we acquire the infinity of the cosmos." That's the key, that’s Antony Gormley's war cry.

The courtyard of the Royal Academy, with its neoclassical facade, is presided over by the statue of its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. These days, the portraitist and promoter of the “Grand Style” in painting, looks askance at a tiny object at his feet: “Iron Baby” (1999) is the sculpture of a newborn, life-sized and curled up on the ground as if it were her cradle - it is based on Gormley's daughter, six days after her birth. The artist says: "Its density suggests energy potential like a small bomb. The material is iron (concentrated earth), the same as the core of our planet.” This projectile-piece sets the tone of the exhibition.

Iron Baby (1999), Annenberg Courtyard, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Antony Gormley was born in London in 1950 into a devout Roman Catholic family: he was baptized with a name whose initials make up A.M.D.G. (Ad maiorem Dei gloriam -To the greater glory of God) which is the Latin motto of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits): "My name is Antony Mark David Gormley and I wasn’t called that by accident." From the age of six, he had to obey the strict rules of his afternoon nap: he would go up to his small bedroom where it was hot, lie down and not move, his eyes closed, while the light flooded his bed mercilessly. In that claustrophobic environment, he felt imprisoned in his incandescent cage, alone with his eyes. Gradually, he began to focus on that enclosed, oppressive space, transforming it into a different place: dark, cool, floating in a deep, blue infinity. Sixty years later, he is a sculptor whose work wrestles with the concept of what it means to inhabit the human body.

Gormley boarded at a Benedictine public school and travelled to Lourdes as a volunteer, all of which shattered his Catholic faith. After graduating from Cambridge, he joined the hippy trail, travelling through Turkey, Syria and Afghanistan to India: "the place where things started to make some sense." He spent two years studying Buddhism: "Passion for meditation took me to a place I’d already been to as a child."

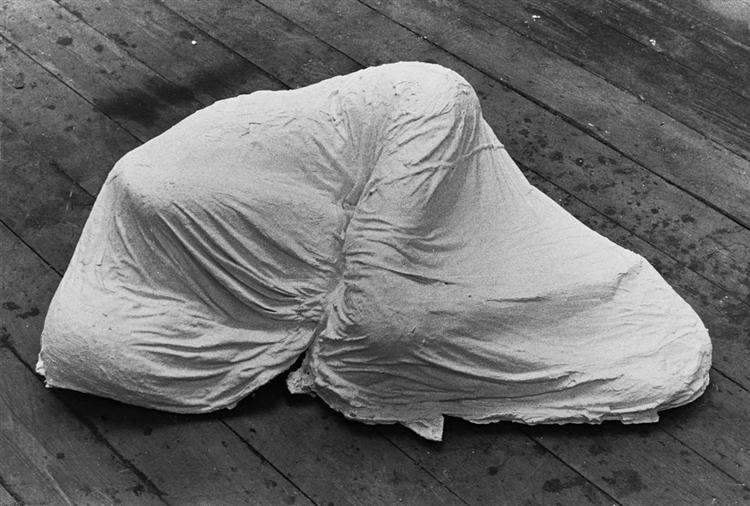

His experience in India planted the seeds for his early sculptures. Sleeping place (1974) is the silhouette of a man lying down in the foetal position, covered by a white cloth. "For two weeks I wandered around Calcutta. The streets were made up of noise, the suitcases, the car crashes, the food stalls on the ground, the rickshaws ... and in the midst of all that were these bodies just lying there, not moving, covered up and noone knew if they were dead or alive. Sleeping Place was my way of turning that experience into an object."

Sleeping place (1974)

Since 1981, Gormley has been working with the body and choosing his as the nucleus for everything. For the next 15 years, Vicken Parsons, his wife, accomplice and only assistant, wrapped the artist's naked body in plaster mesh in different poses, leaving only a hole for his mouth, trimming it and then freeing him from the plaster casing. And so began Gormley’s artistic hallmark, an army of iron men who today populate the world from the English coast to the rooftops of Manhattan. These "bodycase" sculptures - of which Lost Horizon I (2008) is the piece featured in this exhibition, consisting of 24 figures all pointing in different directions from the walls, floor and ceiling, questioning the perception of what is above and what is below - evolved thanks to cutting-edge infrared technology and a custom-made computer program which allowed him to take his dimensions and postures even further, delving deeper into abstraction. Increasingly, schematic "men" began to emerge whose bones, muscles and skin were decoded into computer or industrial forms, physical pixels made of rusty iron, bricks of metal that, like Lego, constitute beings without a name, without an identity. These are the Slabworks (2019) in Room 1.

Lost Horizon I (2008), Royal Academy of Arts, London

Slabworks (2019), Royal Academy of Arts, London

Antony Gormley has just turned 70 and the Royal Academy is thus honouring his trajectory here. However, Gormley’s works, as open-air sculptures, grow with an amplifying force that pierces urban and rural landscapes like acupuncture needles: beaches, deserts, Italian palaces and industrial England’s chimneys ... The sculptor leaves his solitary men there, like a forest of questions, forcing us to understand that place in a very different way. In the words of Simon Schama: "They are actors, not statues."

Another Place (1997), Crosby Beach, Merseyside, Great Britain

Gormley also wanted to give voice to those who did not have one - "One&Other" (2009) with 2,400 volunteers occupying the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square - and "Sculpture for Derry Walls" (1987) was his link to 'The Troubles' in Northern Ireland. Two back-to-back figures in symbolically Christian cruciform form, cast in iron to withstand the impact of bullets, were placed at strategic border points between Catholics and Protestants: "As soon as the sculptures came down from the cranes, a crowd of young people huddled around them, spitting at them. A young man on my team flew at them with a hammer at lightening speed. I will always remember that moment. Those gangs burned our sculptures, hung tires from their necks and set them on fire. The next morning the remains of the scorched tyres looked like crowns of thorns."

Sculpture for Derry Walls (1987), Derry, Ireland

A connection with the spectator has also led him to invite the public to collaborate on the creation of his work. "Field" (1990) is an ocean of small clay figures made in three weeks by a family of brick builders outside Mexico City: "Every time I've done "Field", I've used local people and materials. That time I gave them some very basic instructions: Take a piece of mud, shape it with your hands, make two incisions for the eyes and see what becomes of it, let it make its own shape, which will be unique. What turns out, or better said, what is freed when you give a group of people a common goal? The result is magical."

The first time he did "Field", there were over 1,000 figures. When he did "Field for the British Isles" (1993), the army of small mud men surpassed 40,000. "I tried to physically offer a voice to those who did't have one. I grew up in the 1960s, in an orderly world where ordinary people were gradually reaching positions of power. That's the spirit of "Field", filling up every last inch of a museum so the pleasant experience of being in a museum is transformed into a confrontation with the accusatory looks of thousands of eyes challenging us," Gormley explains.

Field for the British Isles (1993), St Helens, Liverpool, Great Britain

In 1994, Gormley won the Turner Prize which brought him recognition and an infinite launch pad for taking on larger projects. "Angel of the North" (1998) is a 20m high totem pole of 200 tonnes of angel-shaped steel. Its deployed wings stretch as wide as a Jumbo jet’s. Its location, just off the busy A1 motorway near Gateshead, makes it one of the most viewed works of art in the world.

Angel of the North (1998), Gateshead, Great Britain

The spirit of these works can be felt to vibrate throughout the 13 rooms of the exhibition which also display Gormley's drawings and which, like a 21st century Leonardo da Vinci but tinged with blood, oil, earth and flaxseed oil, demonstrate a sculptor's obsession with drawing. They are like diamonds shooting out hard, fast and direct like arrows from the neurons of his ingenuity.

Mould (1981), Private collection

This exhibition is a co-production between spectator and creator. The sculptures demand our physical and imaginative participation: we are obliged to bend down, crawl and lose ourselves among them. Also fascinating is the play on scale with works the size of the palm of one’s hand beside other colossal ones. "Clearing VII" (2019), composed of miles of coiled aluminum tubes tracing an arch between the floor and ceiling and wall to wall, is a "drawing in space" that envelops the visitor. "Host" (2019) fills a room with sea water and mud, evoking the depths from which life emerged. "Matrix III" (2019) is a huge dark cloud of rectangular steel grilles suspended from the ceiling. Although some of his new pieces are abstract, his reference point is always the human body. Da Vinci drew his Vitruvian Man in 1490: "Vitruvius established in eight heads the proportion of man and also that the distance from the chin to the forehead should measure the same as the hand," Gormley says as he moves towards the Matrix III mesh to demonstrate.

Matrix III (2019), Royal Academy of Arts, London

On these last days of summer light, it is still possible to view Gormley’s “Sight” installations on the island of Delos. Like modern-day sentinels, twenty-nine of his iron men defend this floating rock in the middle of the Aegean, whose name means 'The Visible' after Zeus offered it to Leto, his mortal lover, to give birth to Artemis and Apollo. Today, 5,000 years later, sees the first intervention by an artist. His sculptures greet us from strategic points: the seashore, surrounded by poppies on the ground between pillars or as strange companions to the marble gods in the museum …. while having an emotional conversation through the millennia of time. According to Martin Robertson, a British specialist in Greek archaeology, it was on this island that a marble statue depicting a woman appeared in the middle of the 7th century BC from the shrine of Delos. In the skirts of the figure reads an inscription in verse telling us that it was dedicated to Artemis by Nikandre of Naxos. That was the start of monumental sculpture in Greece.

Sight, (2019), Delos Island

But Delos is also inhabited by Gormley sculptures that are more in keeping with that other abstract canon of his - pixelated men, which are surprisingly integrated into what remains of the island's architecture today: catalogued ruins laid in rows of stone blocks by archaeologists. In this sense, it is an objective correlation of the digital age, in which information comes to us in bits that we reconstruct to create an image: "That was the original idea that coordinated the syntax of this exhibition, from these decoded bodies, like material shadows of a living body," says the sculptor.

Sight, (2019), Delos Island

Like David Hockney, Gormley belongs to that group of artists who have dedicated part of their lives to the writing of a discourse on the History of Art. In the BBC documentary 'How Art Began' and with the emotion of an English thespian, the sculptor tours the Paleolithic caves of France, Spain and Indonesia in search of humankind’s first artistic trace and the answer to a question: what triggered in homo sapiens the need to leave their footprint in time? Thus, installations such as "Sight", or "Still Standing" (2011) from the Hermitage’s permanent collection, have allowed him to confront us with his premise using the dialogue of his oeuvre with classical statuary. For Gormley, from Greece to the 19th century there was a single discourse in sculpture: the idealization of the human body. He insists that today times are different, that his work demands the participation of the viewer, that his empty bodies must be filled out by our sensations. "Cave" (2019), the jewel in the Royal Academy’s crown, is a sculpture of architectural proportions, an enormous body transformed into geometric caves with an entrance and exit. What Gormley aspires to is that we enter it and live inside its stomach, its limbs like tunnels of light and feel the cold and anguish inside the head of this Hulk, bursting into steel buckets on the ground. "I try to give the new language of modernity to the body that was rejected earlier as something classical. What I want to do concerns the abstract body, the one that corresponds to the language of Malevich, Picasso... and from there to Donald Judd and Sol Lewitt." Gormley and the past are as a propulsion of his sculpture into the future: two sensations that merge into a single victory.

Antony Gormley

Royal Academy of Arts

Burlington House Piccadilly,

London W1J 0BD

Curator: Martin Caiger-Smith

21 September - 3 December 2019

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Gormley at the Royal Academy: a discourse in iron - - Alejandra de Argos -