Art is in everything, art is in life and it expresses itself on every occasion and in every country. Charlotte Perriand, iconic figure of twentieth century design, demonstrates yet again the importance and influence of her work in a grand exhibition on display until February 24 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Perriand changed the way we inhabit domestic spaces, creating a world full of possibilities unfettered by traditional notions of what a home should be.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Left: Charlotte Perriand at La Vallée, circa 1930 © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP. Right: Charlotte Perriand reclines on « Chaise longue basculante, B306 » (1928-1929) – Le Corbusier, P. Jeanneret, C. Perriand, circa 1928 © F.L.C. / ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP

“Art is in everything, art is in life and it expresses itself on every occasion and in every country.” Charlotte Perriand

Charlotte Perriand, iconic figure of twentieth century design, demonstrates yet again the importance and influence of her work in a grand exhibition on display until February 24 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Perriand changed the way we inhabit domestic spaces, creating a world full of possibilities unfettered by traditional notions of what a home should be. She made use of technical skill, industry and the most advanced materials for her designs. Parts from bicycles, cars and even airplanes were a source of inspiration that would lead to her becoming, over time, a pioneer in the mass production of her own designs.

Almost the entirety of the Frank Gehry-designed gallery has been given over to the exhibition on a chronologically arranged route that welcomes the visitor with a large painting by Fernando Leger, “Le transport des Forces”, and two of Perriand's most iconic pieces, the Chaise Longue basculante LC4 and the B302 Swivel Chair, long and erroneously thought to have been designed by Le Corbusier alone.

As well as Leger, other artists features alongside Perriand throughout the whole tour are, Picasso, Laurens and Delauney.

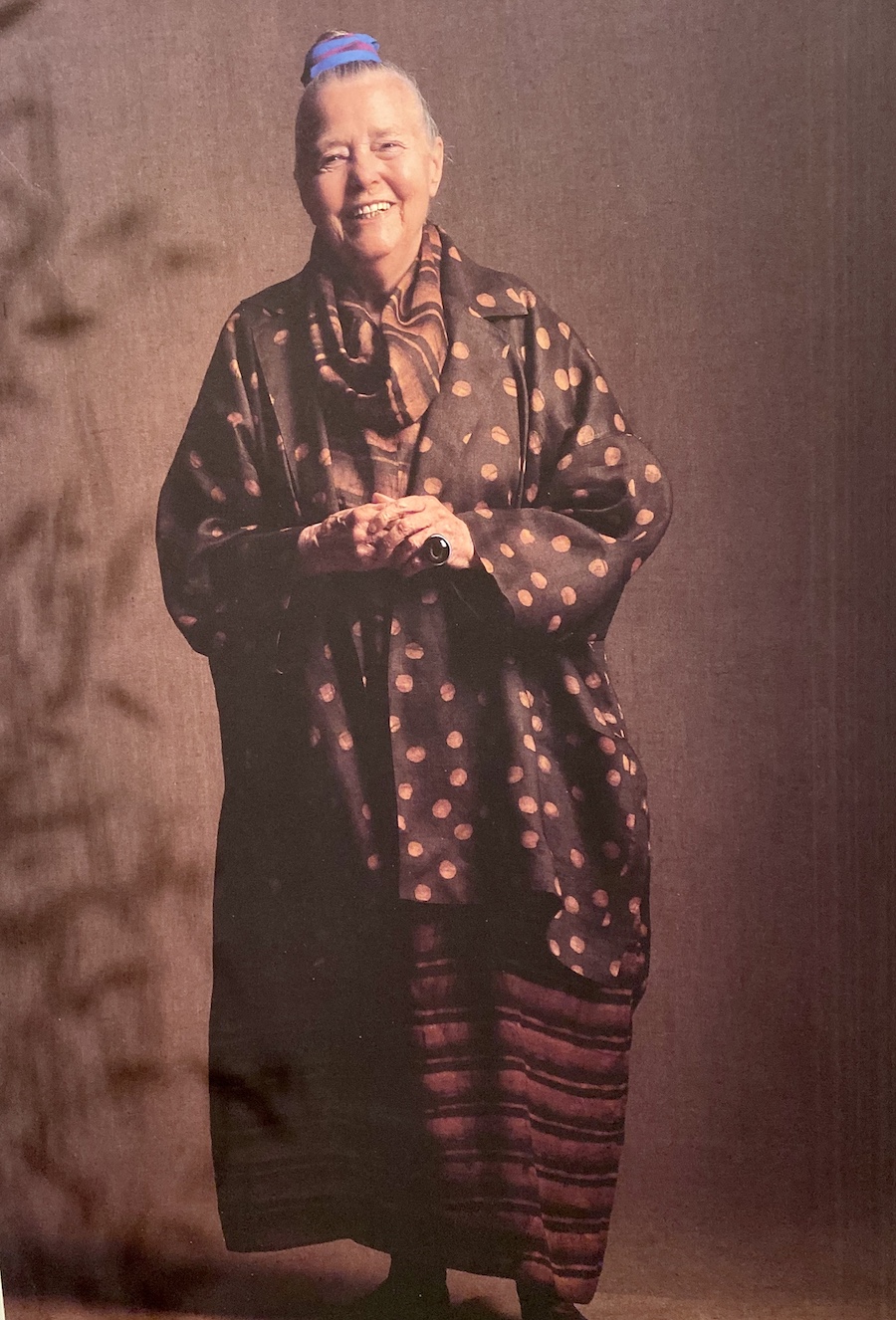

Building modernity, exploring Nature and engaging with other cultures are just a few of the highlights of the Exhibition that define the work of an intelligent woman devoted to her ideas and profession and whose unwavering dynamic vitality endeared her to everyone she met. A tireless traveller, she absorbed life with such intensity that it is sometimes difficult to keep pace with her.

In 1926, a recent graduate and excited by Le Corbusier's theoretical work on new cities and alternative ways of living, she knocked on the door of the studio that the renowned Swiss architect shared with Pierre Jeanneret, the outcome of which was that infamous quote: “Miss, we don’t embroider cushions here”. A year later, Le Corbusier recanted and offered her a contract, having seen, at the Salon of Decorative Artists, her piece Le Bar sous le toit, a cocktail bar that Perriand had designed for her own apartment. Thus began an intense collaboration that would endure throughout the lives of these two innovators. Perriand writes in her memoirs that her role in Le Corbusier and Jeanneret’s studio was to bring the ideas of the two great architects to fruition. She was a practical woman and one capable of solving any problem with her vivid imagination, filling what Le Corbusier called “machines for living” with humanity. In 1952, Le Corbusier called her to design the interiors of what are known as his Unité d’habitation housing developments in Marseille and Berlin. The result can be seen in the Exhibition and illustrates that she knew precisely how to convert those minimal spaces into cosy places, incorporating the first ever compact modular kitchen prototype.

One of the key pieces in the Exhibition is a recreation of the interiors project for the 1929 Autumn Salon, L'Équipement Interieur d’une Habitation, which she created in collaboration with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret. Here, the visitor can interact with the furniture and understand how the arrangement of objects in a space creates the ambience that turns a home into a comfortable one.

In 1929, the pricking of her social conscience led her to participate in the creation of the Union of Modern Artists (UAM), in which Mallet-Stevens, Miró, Calder, Delauney and Chareau also participated. What they sought was the coming together of all arts to respond to the political and societal problems of their time. The Republic of Spain pavilion at the 1937 Paris exhibition was a perfect reflection of the aims of UAM - architecture, sculpture, painting and photography together in a joint portrayal of the tragedy of war. Its curator was the architect José Luis Sert, a great friend and collaborator of Perriand’s, who is remembered in the exhibition with a display of his photographs taken during the Spanish Civil War and a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica, among other items. Both architects shared the same social concerns and collaborated on the design of minimalist housing. In 1933, they participated in the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) where the Athens Charter was drawn up, the widely-known manifesto on optimal conditions for urban living.

A full-scale model of another of Perriand’s iconic works, 1934’s The House On The Edge of the Water, rests on stilts outside the Foundation on and beside a water feature so that visitors can visualise the meaning of the project, intended as a holiday home for families with little money to spare. A kind of self-assembly cabin than can be dismantled, supported on stilts and divided into two symmetrical spaces: one, the living area and the other to sleep in, both with sliding doors opening onto a terrace protected by a canopy collecting rainwater. Again, Perriand is thinking about functionality and aiming to reach the most needy by building a world that is simpler, more humane and closer to nature.

She was also an accomplished photographer who scrutinized Nature through her camera lens, finding solutions for many of her creative ideas there. The sea and the mountains were recurring themes in her snapshots and the inspiration for a series of projects on mountain shelters. In 1938, her Tanneau Mountain Refuge, measuring eight square metres and sleeping six people, was built. “I love the mountains deeply,” she said. “I love them because I need them. They have always been the barometer of my physical and mental equilibrium.”

Her time in Japan and Indochina are very well illustrated in the Exhibition with designs incorporating elements from the East such as indigenous types of wood, bamboo, lacquer and fabrics that reinforced the links between creation and tradition. Brazil, where she got to know other renowned architects and the exuberance of their designs, was another turning point in her career.

The crowning moment of her career would come with the Les Arcs project, a huge apartment complex in the French Alps, with a sleeping capacity of 30,000. Perriand, in a display of ingenuity, developed what has been called minimalist compartments or cells. The interiors were mostly built from prefabricated pieces and boasted large windows with stunning views that brought nature in from outside. A large model serves to help the viewer understand Les Arcs as the culmination of the whole repertoire of Charlotte Perriand’s ideas.

The tour ends with Perriand's last ever commission – 1993’s Maison de Thé for UNESCO’s Paris headquarters: a wooden circle supporting eighteen bamboo canes creating a 4.5 metre high space covered with a domed canopy of leaf silhouettes. A delicate, organic work to celebrate the Tea Ceremony.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World

Louis Vuitton Foundation

2 October 2019 - 24 February 2020

(Translated form the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Le Monde Nouveau de Charlotte Perriand - - Alejandra de Argos -