On 7th March 1500, Emperor Charles V was baptized at St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, a fortnight after his birth. The verticality of the central nave, with its very subtly pointed arches shooting up into the sky, was draped in gold and silver-threaded Flemish tapestries; the Gothic stained glass windows, with their heavenly entourage, fulfilled the symbolic function of transforming the interior illumination into an other-worldly light distinct from that outside.

|

Colaborating author: Marina Valcárcel

|

|

On 7th March 1500, Emperor Charles V was baptized at St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, a fortnight after his birth. The verticality of the central nave, with its very subtly pointed arches shooting up into the sky, was draped in gold and silver-threaded Flemish tapestries; the Gothic stained glass windows, with their heavenly entourage, fulfilled the symbolic function of transforming the interior illumination into an other-worldly light distinct from that outside. A walkway with forty arches was built, each one representing the future states of the newborn and one of the godmothers, Margaret of York seated on a throne, carried the baby, preceded by a lavish royal entourage. This baptism was conducted in the manner of a coronation, leaving behind the simpler medieval ceremonies of the past and instituting this Burgundian ritual in the Spanish crown. But all the pomp and solemnity failed to prevent the eyes of those entering the cathedral being drawn towards the Vijd chapel. There, on 6 May 1432, The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb altarpiece, the Polyptych of Ghent, painted by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, had been inaugurated, offering its awestruck audience a surprisingly new way of viewing art.

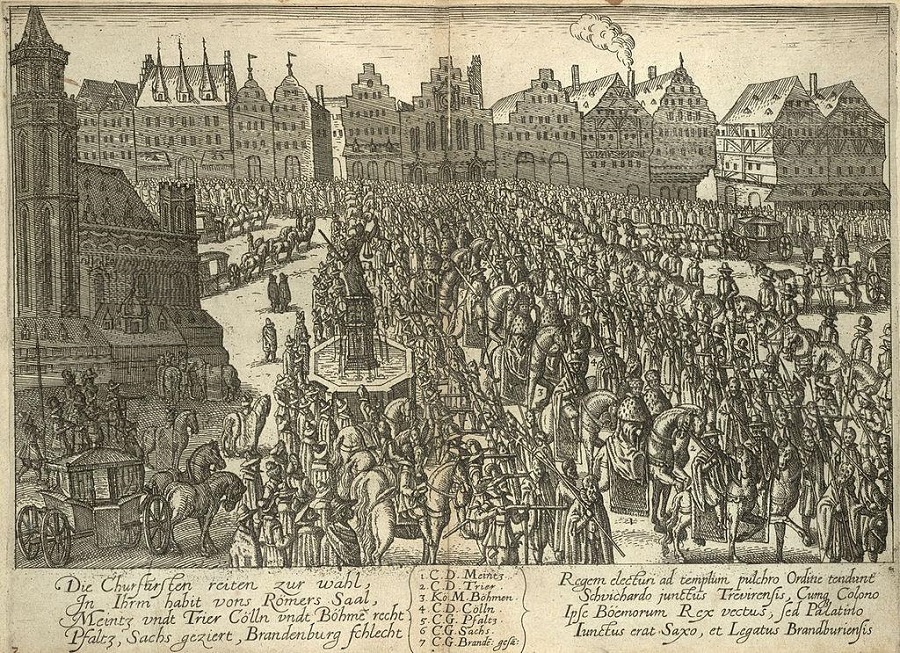

Ceremonial cortege, German engraving, 16th century.

In 2012, a team from the Royal Belgian Institute for Artistic Heritage began restoration of the Polyptych in a laboratory at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MKS). During the first phase, when lifting the different layers of varnish, large areas of overpainting were discovered that - probably since the 16th century - had kept van Eyck's work hidden. For the first time, it became possible to see the outer panels of the Polyptych in their original state: the colours of skies and cities, fabric folds and pins hidden in headdresses, light bathing the skin of its subjects and the illusory feel of simulated marble in the statues of the two Saint Johns. These were findings that allowed for us to intuit and piece together many of the mysteries surrounding the paintings of Jan Van Eyck (Maaseik? c. 1390 - Bruges, 1441). This was what sowed the seed of this unrepeatable exhibition displaying all of the eight panels before they return, forever, to the Cathedral of St. Bavo. They form the backbone of the thirteen mysterious, dark rooms of the exhibition, their walls alternately painted the red and ultramarine of the Virgin Mary's robes and their lighting that seems to emanate from inside the paintings: almost 100 works comprising Masaccio, Pisanello and Fra Angelico, his Italian contemporaries, some of his Flemish contemporaries and, above all ,13 of the 20 known Jan van Eyck paintings in the world, constituting a never-before seen collection.

Laboratory at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MKS). Restoration of the Polyptich

The traveler visiting Bruges will see the small enclosed gardens with their espalier fruit trees and the high pointed arrows of the bell towers emerge around the canals and will be seeing the same streets and their houses and the same churches on the other side of a bridge as Van Eyck. Little seems to have changed since 1430. Similarly, when we stand facing a 15th-century Flemish painting, we believe that we are infltrating the intimacy of life of another time.

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail). Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, Cathedral of St Bavon, Ghent.

Silks and Patrons

The birth of Flemish painting was occasioned by the French defeat at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 which spelt the collapse of France for decades. Far removed from the ongoing Anglo-French Hundred Years War, Flanders devotes itself to its vocation of commerce. The 1419 assassination of the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, convinces his son, Philip the Good, to sever ties with the Valois and move the capital of Dijon to that protected and free city of Bruges into which goods from the Mediterranean, the Baltic and all the luxury ships of the East flowed: spices and pearls, Turkish rugs, silk brocades from Syria ... objects that will inundate the spaces between Van Eyck's Virgin Marys, altars and donors. Bruges was already the well-established centre of a thriving school of illuminators, among whom and under the influence of the greatest sculptor of the time, Claus Sluter, Van Eyck begins to paint the folds of robes as voluminous as portico sculptures and saints' faces contorted by expressions of pain and to let his painting take on the preciosity and colors of the jewelled and enamelled cover of a Book Of Hours. The Duke of Burgundy's court was a paradise for fortunes such as those of the Italian banker Tommaso Portinari or that of Chancellor Nicolás Rolin, who favoured the arts and generated much patronage. In this environment, May 1425 saw Jan van Eyck's appointment as court painter to Philip the Good, for whom he undertakes numerous long and secret journeys of which only one destination is known: the Iberian Peninsula.

Limbourg Brothers: "May", calendar page from the "Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry" (1411-1416). Condé Museum, Chantilly, France

Subdjugating the light

So who was Jan van Eyck? What was his optical revolution in response to? What was it that made him paint that way?

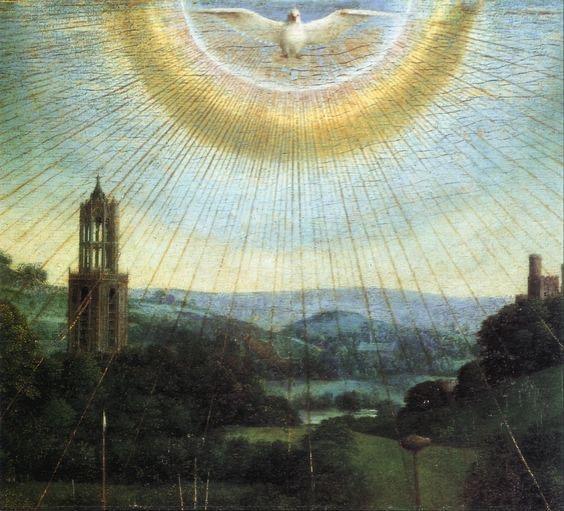

One could say that, as a painter, he enslaved subjugated and conquered light, subduing and taming it until he was able to illuminate every corner of his paintings with it. To achieve this, he made use of the well-established tools of antiquity which he mastered and made his own. The most recent scientific analysis, after the restoration of the Polyptych, shows that van Eyck mastered all oil techniques and took them to their limits, reproducing every possible texture from silk to hair, from stained glass to Valencian tiled floors, crowns, the light from a child's skin or the matte tone of an old man's hand, books, bindings with their gold lettering, the sky and the pale brightness of the setting sun. Likewise, he portrayed a forest breeze, rays shining through the Gothic windows of a church and the whole reflection of a city on a stretch of lake in the background of a Saint Francis whose stigmata glowed with the precise amount of sheen in every drop of congealed blood.

Everything he saw in nature he conveyed with his brush: different types of rocks, variations of clouds and even depictions of skin diseases and no one, except Leonardo da Vinci, managed to paint the human eye with such precision, the eyelids, the veins and the steadiness of a fixed gaze.

Jan Van Eyck, Saint Francis receiving the stigmata (c.1440), Philadelphia Museum of Art

Erwin Panofsky demonstrated how, unlike his Florentine contemporaries, Van Eyck had no interest in applying the mathematical laws of perspective. In The Annunciation scene from the Ghent Altarpiece, the floor and ceiling beams not only do not converge, they do not even come close. In the Washington Annunciation, far from a single vanishing point inside the church depicted, there are several. Van Eyck found an empirical solution for the representation of a compelling space based on direct observation. With it, he came to create twofold perspectives, suggesting distances both panoramic with horizons as real as they are implausible and meticulously detailed - what Panofsky defined as the juxtaposition of his microscopic and telescopic gaze. And so, in the foreground are the interiors his characters inhabit, that intimacy that today fascinates us because we recognize in it our own world, the modern world of the individual and their things: gloves and carpets, musical instruments, lilies and easels and reading stands. That eagerness to portray everything, even what it is not necessary to show, is overwhelming. It is that same domestic and modern intimacy that will later be painted by the likes of Vermeer and De Hooch and Chardin, while in the background or somewhat higher up, another scene unfolds behind a window or on a balcony: a view of a Flemish city, its towers, belfries and streets lost in a horizon of lakes, blue mountains and tranquil skies. Landscapes both infinite and of pinpoint accuracy that in turn, centuries later, a young Ingres would paint in his 1806 "Portrait of Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière".

Jan van Eyck , Annunciation (detail)

Jan van Eyck, Annunciation (c.1430-35). National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Mademoiselle Rivière (c.1793-1807). Louvre Museum, Paris

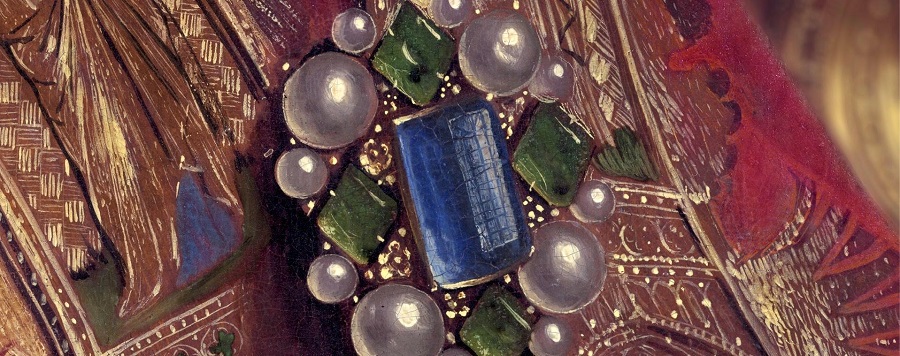

Van Eyck suffered from an obsessive fixation with the way light covers and forms images from reflection and refraction. The mirror must have permeated his world not only as an object, but also as a metaphor. Some of his knowledge came from observation, but in his time he was considered the first pictor doctus (illustrated painter) north of the Alps. He was familiar with classical authors, had read Pliny the Elder, was an expert in geometry, in archaeology, but above all, he knew optics, that Late Medieval science based on the discoveries of Arab mathematicians, such as Alhazen. Van Eyck used and perfected it in the development of an optical revolution that still impacts us emotionally today. The lighting of the Ghent Altarpiece corresponds to the natural incidence of light through the southern windows of the Vijd chapel. Throughout the altarpiece, the light falls from the upper right corner, like sunlight in the chapel on a sunny afternoon in late spring or early summer. The degree of consistency in the lighting of the entire altarpiece is exceptional. In the central God the Father figure, the jewels in his mitre, the focal point of the sceptre's quartz rock crystal and all the points of light in the gold brocade fabric show a high degree of photographic accuracy.

Marc De Mey, who explored Alhazen's influence on Van Eyck, was the first to point out the painter's tour de force conceiving of the alternating rows of pearls and crystal beads hanging from God the Father's gold brocade sash inscribed Sabaut (Lord Sabbaoth His Name): while the former absorb the light from the window, the glass ones project wide reflections of it.

There are hundreds of examples, from the metallic reflection of the red banners on the breast armour of St. Michael and St. George, to the reflection of an entire window in the huge central sapphire of the principal angel's brooch in the Angels Singing panel. The tracery of that window was scratched out with the very tip of his brush, saturated with white paint, using the sgraffito technique.

Angels Singing (detail), Ghent Altarpiece (1432), Saint Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent

What is also magical is the mastery the Flemish painter brings to painting the water flowing and splashing in the Altarpiece's fountain, as well as in The Virgin of the Fountain. Lighting plays a central role in its realism, but so does movement in the leap of every drop. The water flowing from the mouths of both sources is painted in fine, white, irregular and intermittent lines. It's as if Van Eyck had spent an afternoon with Bill Viola watching the water in his videos suspended in motion.

Jan van Eyck, Virgin of the Fountain (detail), 1439, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Flanders versus Italy, 1430

The exhibition pits Flemish paintings against their Italian contemporaries in a dialogue that reaffirms our question: What is it that makes Van Eyck seem like a comet flying over the 1430s in the European artistic firmament? Jacques Lassaigne and Giulio Carlo Argan have stated that the Renaissance was not a typical Italian movement that spread through other countries in a kind of progressive conquest, but rather a European phenomenon even though it happened differently in Flanders, Italy, France and Germany.

The beginning of the 15th century was witness to one of the greatest revolutions ever known in the history of painting. While Van Eyck paints the Altarpiece in Ghent between 1426 and 1432, Masaccio in Florence between 1426 and 1427 paints the Brancacci chapel, in the Carmine church. Italy favours form over concept; Flanders over experience. These two major works, created almost simultaneously by men so different in origin and tradition, are the pillars of a new painting.

Masaccio, The Expulsion From The Garden Of Eden (c. 1426-1427). Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

Masaccio continued to paint the walls of the Brancacci chapel al fresco with his Adam and Eve ejected and with anguished expressions in his Expulsion from Paradise but they cannot today touch their more serene, more disturbing namesakes in Ghent. There are, however, other revolutionaries in Italian optics: Gentile da Fabiano, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi ... with whom stylistic comparisons are inevitable, interesting: in Virgin and Child with Angels by Benozzo Gozzoli (1449-50) compared with van Eyck's Virgin of the Fountain (1439) the results from the same ultramarine pigment for the color of the Virgins' robes is very different: the tempera more opaque in the Italian and the crystalline glazes, much more intense in van Eyck. Also the enduring Italian penchant for gold leaf as opposed to the naturalistic focus of Eyck's painting which replaces the old-fashioned golden backgrounds with landscapes; the halos which cease to be large discs surrounding holy heads in favor of lighter golden rays; and gold objects which are no longer depicted with real gold but with yellow and brown paint to simulate light, form and texture.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Virgin and Child with Angels (c.1449-1450), Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail), Ghent Altarpiece

Absences

The penultimate room of the exhibition, dedicated to portraiture, is perhaps the most underwhelming. Tzvetan Todorov has said that when you walk through the halls of a large European museum, a radical change in the very nature of the paintings is visible as we pass, say, from 1350 to 1450. He explained that in northern Europe there was no Renaissance in the sense of a rediscovery of Greek and Roman civilization as a means of doing something new. Rather, the search for a new way to account for equally new experiences is what one observes. The common denominator in these changes is not the rediscovery of antiquity, but the discovery of individuality. Therefore, at that time, the individual portrait was invented, and has remained an art staple ever since. Men have taken the place of God in the system of universal symbolism.

Jan van Eyck, Baudouin de Lannoy (c.1435), Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museum, Berlin.

And so ends the exhibition, after the Crucifixions and the Annunciations, with the heroes of more recent times. There are six portraits of Jan van Eyck along with those of his Italian contemporaries Pisanello, Michele Giambono ...

Then, in the middle of the room, the only doubt about this extraordinary exhibition occurs to us: Where is Antonello da Messina with his delicate oils on wood? Moreover, where are the great Venetian Renaissance artists Vittore Carpaccio, Gentile and Giovanni Bellini?

We half-close our eyes and imagine ourselves in another room, solitary, painted blue, empty except for Man In A Red Turban (1433) by Jan Van Eyck facing Vittore Carpaccio's Man in a Red Beret (1485). Wouldn't that be a fight between Titans: a duel of two portraits gazing out at us, face to face.

As Jan van Eyck signed his motto: "Als ich can" (I did the best I could).

Left: Jan van Eyck, Man in a Red Turban, 1433. National Gallery, London. Right: Vittore Carpaccio, Man in A Red Beret, 1485, Correr Museum, Venice

Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution

Museum of Fine Art Ghent

Curators: Till-Holger Borchert, Maximiliaan Martens and Jan Dumolyn

Click here for a 360º Virtual tour of the exhibition

Virtual Live Tour conducted by Van Eyck expert and co-curator Till-Holger Borchert

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)