Two lives parallel in time, two like-minded ways of understanding the world and a piece of drawing paper that would forever bring together two of the great creatives of the first half of the 20th century. I refer to Paul Klee (1879-1940), Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and "Angelus Novus", a small work of art measuring just 32x24 cm and monoprinted in 1920.

|

Collaborating Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Angelus Novus

"Since Homer’s time, the greatest narratives have followed in the wake of great wars, and the greatest narrators have emerged from the ruins of devastated cities and landscapes.” H. Arendt

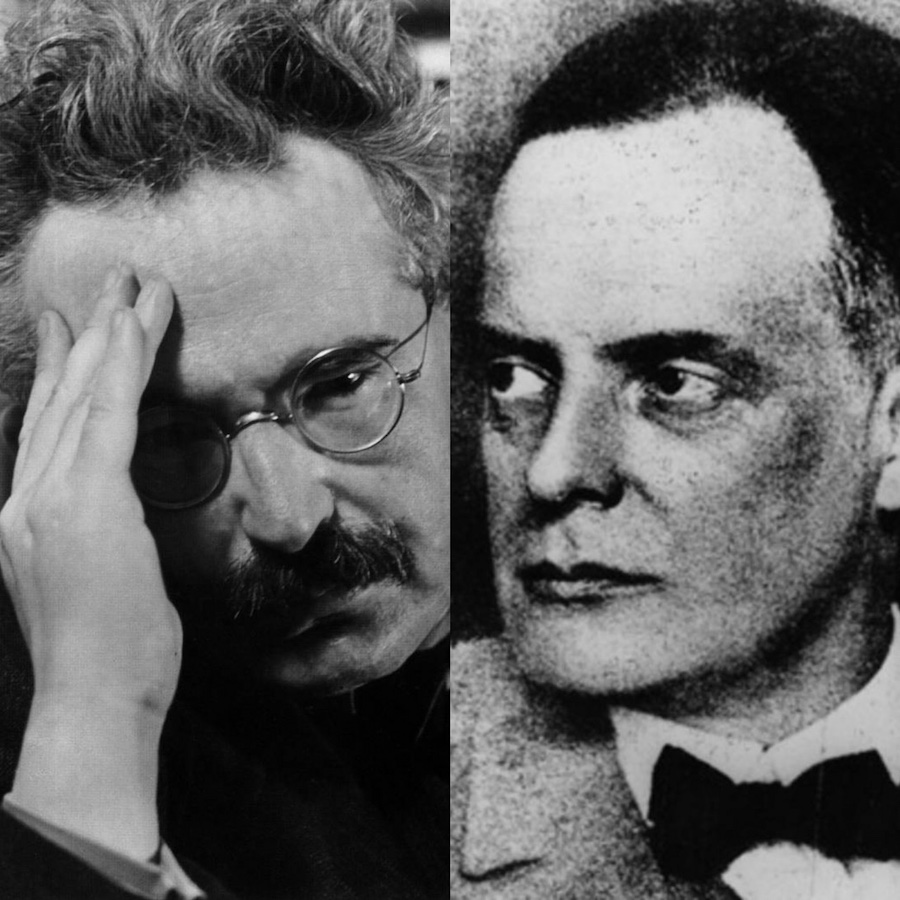

Two lives parallel in time, two like-minded ways of understanding the world and a piece of drawing paper that would forever bring together two of the great creatives of the first half of the 20th century. I refer to Paul Klee (1879-1940), Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and "Angelus Novus", a small work of art measuring just 32x24 cm and monoprinted in 1920.

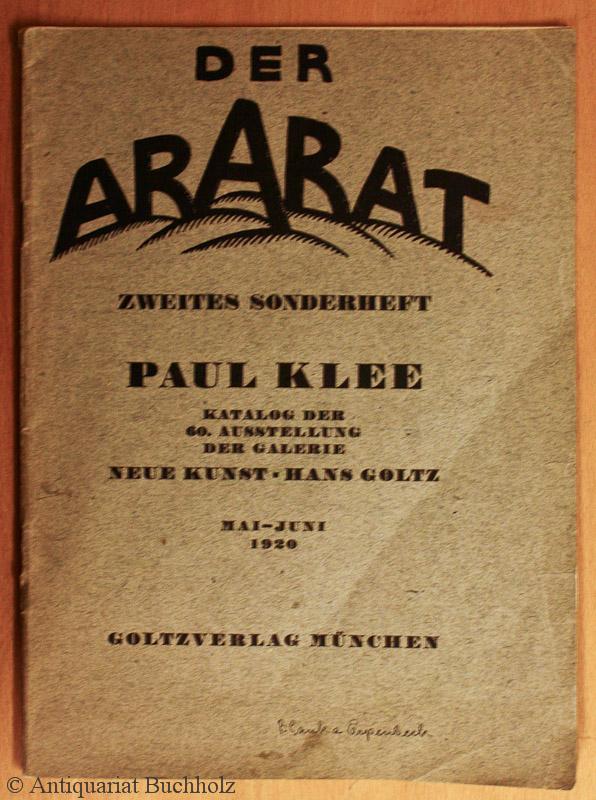

During a June 1921 visit to Munich, Walter Benjamin, accompanied by his long-time friend Gerschom Scholem, visited Hans Goltz's gallery on Odeonplatz to buy the "Angelus Novus", a painting that had had such a profound impact on him a year earlier in Berlin.

Klee had for some time been seeking out new ways to portray reality and new figurative possibilities. In his book "Creative Confession" of 1920, he begins by saying, "Art does not reproduce the visible, rather, it makes visible [what is invisible]." A tendency towards the abstract is inherent in linear expression and rightly so: graphic imagery confined to outlines has a fairytale quality whilst at the same time achieving great precision.

For Klee, form would become the catalyst element deriving naturally and directly from the imagination to unleash a new creative freedom aimed at expressiveness and immediacy. The figurative should blend with one’s conception of the world (1916). It is through the artist that Nature creates.

Angels, by definition of an uncorrupted nature, are a form of direct expression and an attempt to balance out the progressive, technological world with the spiritual world, of which Benjamin would later speak. They constitute a symbolic resource that captured the outrage he felt for all that was happening at a time of immense uncertainty in which certainties had lost their value. He needed to fantasize and angels were a means by which to go beyond a reality that was too prosaic. "To extricate myself from the ruins, I had to fly. And so I flew. In this shattered world, I only live in remembrance, just as sometimes one thinks of something from the past. That's why I'm abstract with memories" (1915). The same ruins that would later pile up at the feet of the 'angel of history'.

"The more terrible this world becomes, as is now the case, the more abstract art becomes." (1915). That year, his friend and fellow artist Franz Marc died on the Western Front at the Battle of Verdun. Klee and Benjamin shared a turbulent world that made its mark on their lives and work. They were both looking for a way to shape their thinking. For Klee, what we perceive is a proposition, a possibility, the authentic truth at its base, albeit invisible (1916). For Benjamin, the truth is in the most insignificant representations of reality.

“Something new is announced, the diabolical is inextricably linked with the celestial, dualism will not be treated as such but in its complementary unity. Conviction already exists. The diabolical is already peeking out here and there again, and it is impossible to suppress it. For truth demands the presence of all the elements as a whole." (10 June 1916). Again the image of the angel is conjured.

Benjamin gives us an account of his own interpretation of Klee's painting, without in any way compromising the artist's intentions regarding these images of contemporary angels that interested him so much and harboured so many ideas.

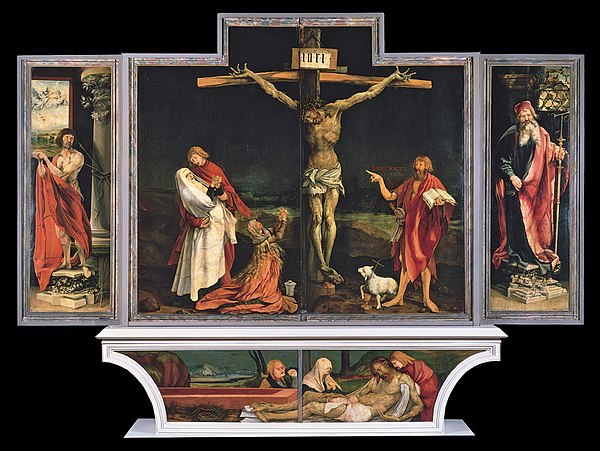

The "Angelus Novus" image became a recurring obsession in Benjamin's thinking. It always took pride of place in his studio and it seems he positioned it next to a reproduction of the Isenheim altarpiece by the German painter Mathias Grünewald, a work of tremendous drama that strips human misery bare. Might he have seen parallels between the two images?

The Crucifixion. Central panel of the Isenheim altarpiece. Matthias Grünewald. Museum of Unterlinden, Colmar, France

The head of the "Angelus Novus" is covered with strylised, curly hair and disproportionate to the size of its body. The feet resemble bird's claws and the wings are attached to the hands. The body houses a pendulum inside a tower ~ that harmonious and silent element marking movement and time that so intrigued Klee and so tormented Benjamin. Huge, wide-open eyes stare past us, to somewhere outside our field of vision. His mouth is half-open and it looks like he is about to say something. The "Angelus Novus" is bringing a message and awaits an answer through his outsize ears. Everything seems to fit for Benjamin ~ this is the Angel of History. Things reveal their significance to him in secret.

There is a painting by Klee called "Angelus Novus" depicting an angel contemplated and fixated on an object, slowly moving away from it. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth hangs open and his wings are outstretched. This is exactly how the Angel of History must look. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it at his feet. Much as he would like to pause for a moment, to awaken the dead and piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Heaven, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which he turns his back, while the heap of rubble in front grows sky-high. What we call progress is this storm.

This is the full text of thesis IX from "On the Concept of History", an essay comprising eighteen theses that constitute a reflection on the idea of progress and its consequences within the concept of history. This was a cornerstone of Walter Benjamin's thinking wherein he questions the era of modernity and the idea of progress it underpins, through one’s ability to give material form to the invisible. Written during his last months in Paris, on the eve of its German occupation, and concluded days before he left the city for a failed exile. His plan was to cross Spain into Portugal and there embark on route to the United States where his friends, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno and the Institute of Social Studies awaited him.

Deeply worried about an overly uncertain future and before leaving the French capital, Klee entrusted his friend George Bataille with a suitcase containing his most treasured possessions, the "Angelus Novus" and his latest writings, among them the manuscript of "Theses on the Philosophy of History", with instructions that, should anything happen to him, he would ensure they reached Theodor W. Adorno. The essay was published by Adorno in a special issue of the Institute of Social Studies in 1942, thanks to the copy that Benjamin had given to Hanna Arendt and which she, albeit reluctantly, passed on to Adorno. The painting ended up in the hands of Gerschom Scholem, at Benjamin's express wish. Scholem's book, "Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism", had been a fundamental inspiration for his work and is currently part of the Jerusalem Museum collection.

The "Angelus Novus" is an exceptional representation of the importance of movement in transformation and evolution and of the importance of looking to the past to build the future. The passage of time has only served to increase its powerfulness and seal its immortality.

Walter Benjamin and Paul Klee

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Paul Klee -Angelus Novus- Walter Benjam - - Alejandra de Argos -