En los días en que se escriben estas líneas, el fondo de la Tierra ruge y escupe ríos de lava desde el volcán de la isla de La Palma inundando la prensa de imágenes dramáticas. Mientras António Guterres desde el G20 y en referencia a la crisis climática, ha dejado en el aire frases como ésta: “Estamos cavando nuestras propias tumbas”.

Lucifer (1890) by Franz Von Stuck. National Gallery For Foreign Art, Sofia

At the time of writing this review, the bowels of the earth roar and spit rivers of lava from a volcano on La Palma in the Canary Islands, flooding the media with dramatic images while at the UN Climate Change Conference, António Guterres leaves us world-shattering statements such as "We’re digging our own grave".

Meanwhile in autumnal Rome, dawn breaks, plastered with posters of the Inferno exhibition from which a demon’s hallucinating, magnetic eyes stare out as we wander from the Pantheon to the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere. They are the eyes of Franz Von Stuck's Lucifer (1890), chosen to announce the most astonishing exhibition of the season at the Quirinal Scuderie and the first ever dedicated to this subject. Closing the city’s commemoration of the 700th anniversary of Dante's death, its curator, Jean Clair (Paris, 1940) offers us a journey through over 200 works on loan from 80 museums in Italy, the Vatican and Europe that, from the late Middle Ages until today, have represented Lucifer and Hell: from Fra Angelico to Botticelli, from Bosch to Goya and so on up to present-day Kiefer and Barceló.

Inferno is an invasive exhibition. Instead of descending towards hell, the exhibition kicks off up a wide, well-lit and circular travertine staircase - because the entire exhibition space is a sort of infernal cave, without windows or natural light - that leads to a wall on which are projected black and white scenes of Dante and Virgil’s voyage through the underworld that are the fabric of Francesco Bertolini’s 1911 silent film L'Inferno.

Still from L'Inferno (1911): Dante and Virgil begin their journey

As in other exhibitions, the first room and the last are those with the highest impact that stay with us for days afterwards. We start off in a magical room dominated by the over six-metre-high plaster cast of Rodin's Gates of Hell (1880-1917) on which he worked until his death and which he never got to see cast in bronze. Within it are sculptures that later became autonomous figures to which he owes his universal fame: The Kiss, representing Paolo and Francesca or The Thinker, Dante personified.

The Gates of Hell (1880-1917) by Auguste Rodin. Musée Rodin, Paris

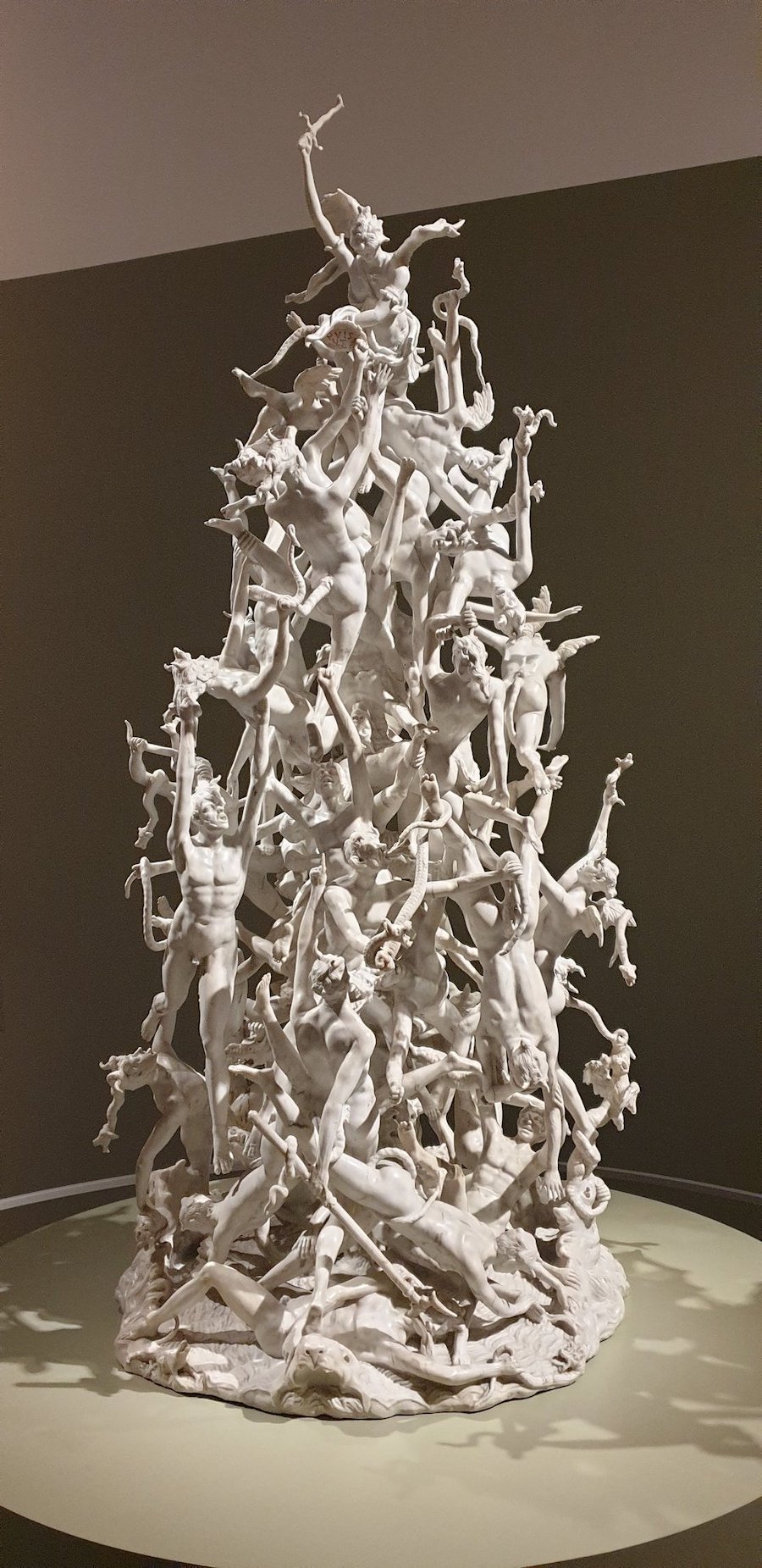

The other six pieces in the first room, although smaller in size, are perhaps even more striking: Fra Angelico's The Last Judgment (1425), Gil Ronza’s Death (1522), a life-size grisly skeleton in polychrome wood, wrapped in a shroud and holding a gilded trumpet. Or Francesco Bertos’ sculpture The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1725), a block of marble just over a metre high perforated by a cannetille of myriad tiny demons whose tails, horns, flames and swords intertwine in a display of virtuosity which makes the Carrara marble seem as if chiselled with plastic versatility.

Death (1522) by Gil de Ronza. National Museum of Sculpture, Valladolid

There are exhibitions where its creator’s original idea is all but paramount and this, without a shadow of a doubt, is one of them. Moreover, it comes with an ensemble of works of unquestionable calibre. It is perhaps for this reason that Jean Clair’s name appears on the posters so prominently, in a typeface almost as large as the title of the exhibition itself. A member of the Académie Française and one of today's most respected yet controversial critics and curators, Clair bids farewell to his career with an exhibition as apotheotic as it is apocalyptic in which he has invested all of his academic knowledge gleened from probing art's attraction to ugliness. Interviewed in Il Giornale dell'arte, Clair said, "The theme of hell has gripped me for a long time. It is a complex subject, probably the most complex that the West has ever invented."

Fall of the Rebel Angels (1725-35) by Francesco Bertos. Banca Intesa San Paolo, Gallerie d’Italia-Palazzo Leoni Montanari, Vicenza

Rodin's Gates of Hell, which seem to welcome visitors and turn them into modern-day companions of Dante, open the way to a large room packed full of works with, at the far end, a painting similar in size, Sir Thomas Lawrence’s five-metre-high Satan summoning his legions (1796). Also in this room are various paintings that portray the topography of evil: from Jan Bruegel’s Aeneas and the Cumaean Sibyl in Hell (1604) to Dante and Virgil in Hell (1880) by Gustave Courtois which, in this exhibition, depicts the only hell of ice.

Dante and Virgil in Hell (1880) by Gustave Courtois. National Centre for Visual Arts (CNAP), Paris

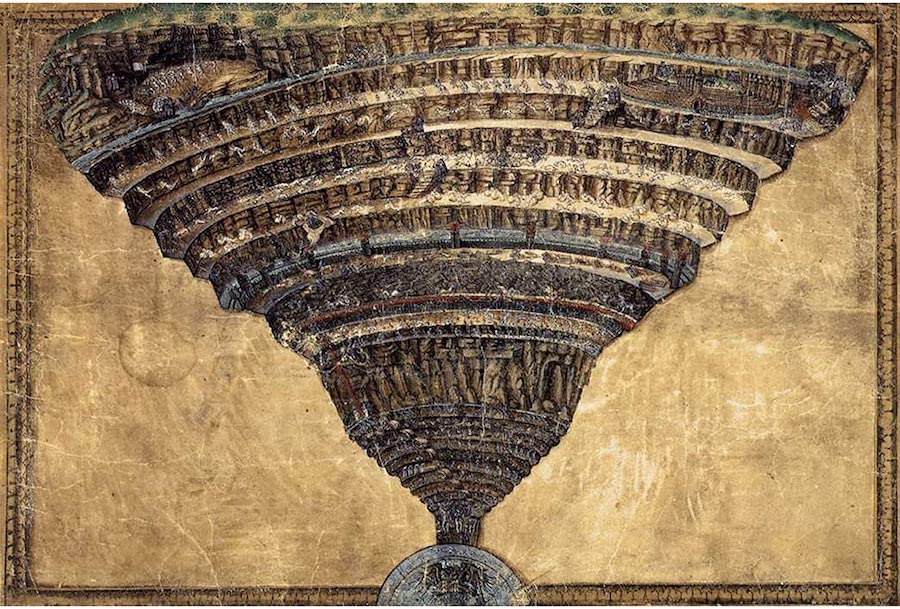

The texts and canvases rub shoulders with photographs and fantastical illuminated manuscripts such as the Liber Floridus (13th century) with its protagonists dressed in chain mail and riding centaurs surrounded by cherubs, monsters, tridents, furnaces and Latin cartouches. In a section of the room dedicated to Dante and the genesis of the Divine Comedy, there are works by Gustave Doré and Miquel Barceló, as well as Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti’s Dante and Virgil (1630), standing guard over a glass display containing Botticelli’s breath-taking Map of Hell. Which reminds us of Galileo’s 1587 description: "Dante establishes the difference between circles and rings. Take, for instance, the seventh, divided into three rings. The outer one with the greatest circumference is a lake of blood and it encloses a middle ring which is a forest of brushwood which in turn encircles the innermost ring which is a field of sand". What inspirational power was it that led thinkers and painters to portray this place with such precise, and at the same time chimerical, accuracy?

Map of Hell from Divine Comedy (1481-88) by Sandro Botticelli. Apostolic Library of the Vatican, Vatican City

The exhibition explains how in the Hebrew Bible, Satan (The Accuser) is a counsellor of God opposed to humankind. Likewise, the serpent of Genesis, coiled in his tree and having Adam and Eve banished from Paradise is interpreted as the personification of Satan. In apocryphal literature and in the New Testament, this figure will be transformed into a powerful being: the Devil (from the Greek, diabolos, slanderer), a concept that perhaps has its origins in Zarathustra.

Lucifer, or "Light Bringer" in Latin, is the name historically assigned to Satan in the Christian tradition. The Book of Ezekiel describes him as a cherub with wings outspread, walking around God’s Garden of Eden, full of wisdom and beauty, his mantle studded with topaz, onyx and sapphires but whose interior became corrupted by pride and rebellion and the desire to be just like God who turned him into ashes and cast him into the void.

In the New Testament, the devil’s role be that of the tempter of humankind but, above all, the tempter of Christ. He is also the destroyer, the spreader of disease, the persecutor of believers and the corrupter of Judas.

During the Middle Ages, the kindness of St. Francis and St. Bernard contributed to the devil’s transformation into an almost comical character surrounded by kitchen utensils, pots, pans, grills and forks. The Renaissance would find in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch some of the most formidable representations of the legions of hell assaulting the damned with the strangest of objects, night skies illuminated by lava-coloured lights and the most oneiric tortures. However, the Romantics and Symbolists would represent Lucifer in the form of a fallen and melancholic angel, meditating on his own destiny.

Tondal's Vision (1500) by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch. Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid

If the exhibition could be divided thematically between two floors, the lower one would contain those works linked to Hell after death while the upper one would be devoted to the hells manifested on earth. Here reside madness, totalitarianism and war: from the era of the Industrial Revolution and its “dark satanic mills”, coal mines and Piranesi's prisons to the terrifying hell of asylums, wars – featuring works by Goya and Otto Dix - dictatorships and the Holocaust.

Room for "agitated women" at the San Bonifacio hospital in Florence (1905) by Telemanco Signorini. Civic Museums of Venice Foundation, Venice

In addition to painting and sculpture, ample space is given over to manuscripts, graphics and the string puppets of Palermo. Inside a display cabinet in this section, it is exciting to see the pages of Jewish-Italian author Primo Levi’s If This Is A Man (1958), with his annotations and corrections handwritten above the typewritten letters. In them, one can sense the same determination with which he typed the account of his incarceration at Monowitz concentration camp.

Finally, we leave the horror behind as Monsieur Clair gives the visitor the opportunity to step out of the darkness and see the stars again. The projection of a still photo of the firmament taken from NASA's Hubble telescope is the gateway to the last room of the exhibition. It is really difficult for anyone, man or woman, to try and emulate the depth of the mystery of the universe. Nevertheless, the small room that opens before us offers a hopeful and luminous outcome. It is presided over by Barjac-based German artist Anselm Kiefer's painting Falling stars (1995) and features a man lying on the ground in a sort of peaceful, mortal sleep under the immensity of a black sky ablaze with shooting stars. Opposite this painting is one of his sculpture-books representing constellations of stars in acrylic on pewter. The rest of the works on display are other emotive portrayals of the heavens by Thomas Ruff and Gerhard Richter.

Falling Stars (1995) by Anselm Kiefer. Private collection, London

After this dazzling room, the visitor emerges, only to be blinded by the daylight, onto a glazed third floor with a panoramic view of Rome, its roofs, its terraces with washing hung out over pots of boxwood, Trajan’s Column and the remains of the Forum at our feet. And at that moment, the final words of the Divine Comedy resonate with us again: "And then we went out to see the stars".

The Triumph of Death (detail) (1336) by Buonamico Buffalmacco. Wall fresco, Camposanto, Pisa

Scuderie del Quirinale

Via Ventiquattro Maggio, 16. Rome

Curator: Jean Clair

15.10.2021 - 9.1.2022

Translation from the Spanish "Infierno" by Shauna Devlin