Courage, that virtue exhibited by some mortal beings, is what I would highlight about the Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru, 1936). The writer is devoted to any number of activities with a discerning spirit. Destined to live a disciplined life, as a life of literature demands, he does not hesitate when circumstances require him to take action; for example, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency of Peru in 1990. At the time he believed his moral duty was to become an active participant in public life and, as a democrat, to denounce authoritarian governments wherever they may be found. Or when he went on stage to act for his love of the theatre and, in short, so many other things one might mention… Working in his study, surrounded by books, I am greeted by the Nobel Prize winner, who raises his head upon my arrival with a smile and that pleasant tone of voice of the people of Lima. How are you?

Author: Elena Cué

Courage, that virtue exhibited by some mortal beings, is what I would highlight about the Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru, 1936). The writer is devoted to any number of activities with a discerning spirit. Destined to live a disciplined life, as a life of literature demands, he does not hesitate when circumstances require him to take action; for example, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency of Peru in 1990. At the time he believed his moral duty was to become an active participant in public life and, as a democrat, to denounce authoritarian governments wherever they may be found. Or when he went on stage to act for his love of the theatre and, in short, so many other things one might mention…

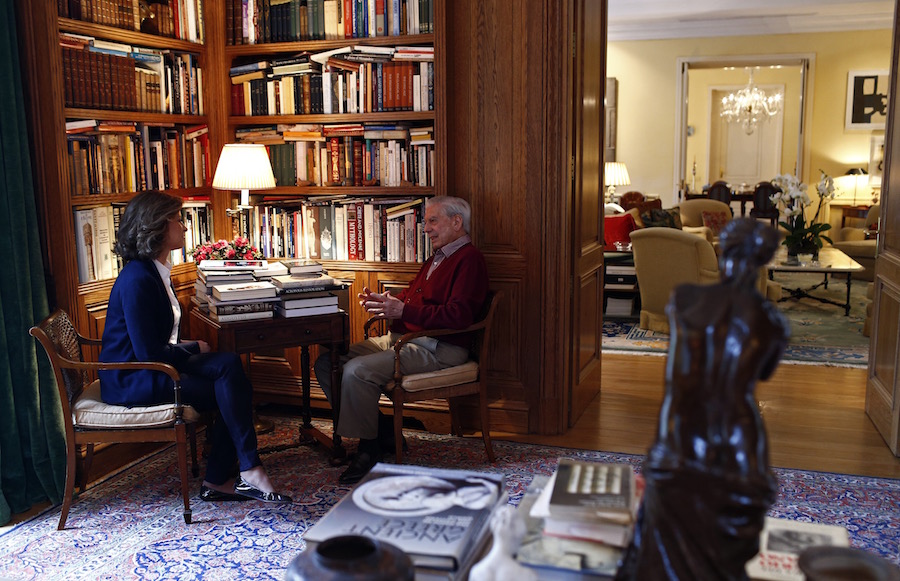

Working in his study, surrounded by books, I am greeted by the Nobel Prize winner, who raises his head upon my arrival with a smile and that pleasant tone of voice of the people of Lima. How are you?

Elena Cué: Why don’t we begin by talking about your latest novel, Five Corners, to be presented tomorrow? What does this novel mean to you at this time of your life and your literary career?

Mario vargas Llosa: Well, this novel, as practically all the stories I tell, came about in a way that is very mysterious to me. I had an idea, which was to tell a story about yellow journalism, that is, sensationalist journalism, which I believe is one of the hallmarks of our time. I think yellow journalism is something that appears everywhere, in the underdeveloped and developed worlds alike. And it is a kind of journalism that played a significant part in the Fujimori dictatorship, when the regime used the sensationalist press to intimidate the opposition, to try to tackle opponents with the threat of a scandal –a scandal that had nothing to do with their profession, but with their private lives, and which so often consisted of merely artificial fabrications, slanders to smear and discredit them. This was systematically used by the dictatorship against all its detractors.

The book begins with an unconventional erotic situation…

I think that it is the treatment of what is erotic which determines whether the erotic is elegant or vulgar, subtle or crude. It is the treatment, the words, the way the entire scene is conceived… In and of itself, eroticism entails a certain amount of civilisation. I think that in a primitive society or people there is no eroticism. Sex is the venting of instinct. In sex the animal component prevails over sensitivity, over the formal component. Eroticism is born at a time in civilisation when sexual instinct becomes deanimalised and enriched with contributions from art and from literature. A world of theatricality emerges around the act of love. And this is eroticism. When this is degraded or debased –due to poor performance, ineptitude, the lack of skill of whoever describes or depicts it– pornography then appears. But I think that eroticism has to do with civilisation, with a concern for social mores, with a certain culture, which is what really sublimates pure sexual instinct.

Then we must speak of Freud… Do you agree with the concept of sublimation of sexual desire as artistic creation?

Yes, without a doubt. I think he was very right about this, and I also think he was very right about sex being a primordial function of life. But it is neither excluding nor exclusive. When, for instance, in literature and art in general, sex prevails in such a way that it manages to obliterate the rest, it becomes something very artificial, something that does not truly represent what real life is. I don’t think that the perspective of sex is essential to understand everything. Psychoanalysis went this far, Freud went this far, but we must take a step back from his genius, which is indisputable.

Can the imagination sublimate an erotic experience in such a way that it surpasses the actual experience itself?

I think that the imagination, sensitivity and culture can enrich the erotic experience in an extraordinary manner, but to go as far as to exceed reality, I think not. Reality is the richest thing there is, the most important thing there is. Our imagination allows us to live an artificial life that is wonderful, extremely rich, but I don’t believe any artist would dare to say that artifice is better than real life.

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

Have you ever been surprised when you have re-read what you’ve written and wonder how it was you who produced it?

Yes, I am always surprised when I write. I would go as far as to tell you that the most exciting and most stimulating moments when writing a story happen when sudden things emerge. For example, in Five Corners, there is a character who, when I created him, was going to be a relatively minor one, a sort of secondary character. However, as has been the case on other occasions, this character started to gain strength, began to grow larger as I developed the story, as if, on his own initiative, he had decided to take on an increasingly important presence. I believe that these are the most fascinating moments. Suddenly a character comes to life…

And what barriers do you have to overcome in your creative process?

Well, perhaps the greatest one is lack of confidence. You know, contrary to what one might think, the fact that I spend a lot of time writing, or that I have published many books, does not give me confidence: on the contrary, it increases my insecurity. Perhaps because due to greater self-criticism or perhaps greater ambition. But the insecurity I feel when I begin a story, whether it is a novel, a play or even an essay, is much greater than when I wrote my first works. However, I know that with the help of perseverance and constant work, I can defeat that lack of confidence.

I assume that for a writer, writing is a way of life. You observe and analyse everything in a different way to the rest. Where do you think these differences lie?

Your question refers to an expression that is similar to something that Flaubert wrote, which was “writing is a way of living”. I believe that this is totally accurate. Although the way it is done varies from writer to writer, of course, I do believe there is a kind of dedication, of devotion, that means the writer also carries a kind of spy within him who, while experiencing –taking part in real life, with friends, lovers, frustrations– there is someone within who is watching it all and deciding how it might best be used in his work as a writer.

In your case, what has proven more fertile for your literary inspiration: suffering or happiness?

I think it is wonderful to experience happiness. I do not think it is a raw material, at least in our time. Perhaps in the past, during certain times; but in our time literature, art, creativity are sooner fired by adversity, negativity, fear, pain, resentment, suffering, than by enthusiasm, excitement, happiness… I think this is why the art of our time has a somewhat dramatic and tragic slant. It is not an art or a literature of contentment, of acceptance of the world as it is. On the contrary, I believe that there is a very strong rebellious spirit in all manifestations of the art of our time and this is basically because it is fundamentally much more inspired by what is negative than what is positive in life.

Perhaps artistic creation is a way to mitigate pain, a way to channel negative emotions…

Exactly, a way of expressing a kind of frustration of resentment or even nostalgia for something you do not have.

And can one get to feel that release through whatever artistic language: painting, writing?

Art is a form of knowledge. Art helps you get to know the life you live in a deeper, much more intense way, because there is usually little distance with the life one lives. But art provides you with that perspective, that horizon, which enables you to understand the world as it is, the drivers, the mechanisms lurking behind behaviours. This description of a secret reality is what art provides, much more than history, sociology and any other social science.

And can one feel that release?

In the end it feels, indeed, like a catharsis. You unburden yourself from what seems like an enormous weight. But you only discover what it is and what is looks like when you are able to express it, via literature, painting, music or any other creative manifestation. You can feel really bad but you don’t know why. And I think that one of the wonders of art is that is enables you to articulate that which is uncertain, confusing, a source of terrible angst. But how wonderful when you see that art gives it a shape and makes it communicable. Many times that sensation, those moods… you don’t know where they come from. One suffers from these moods, but one lacks a deep explanation for them. And I believe that this can only become clear when literature or art allow you to stand back and to appreciate life with all your feelings, instincts and intuitions. I think it is one of the main roles of art: to portray that which is the deepest, the most secret within us.

Then you have succeeded, perhaps, in getting to know yourself by expressing yourself –probably that which you say you don’t know what it is, that comes from the subconscious, in a non-instinctive manner– and have been able to recognise it later.

Sometimes you are surprised and others you are frightened. You ask yourself: “Was that inside of me? Did I have that inside? Where did that come from?”

Of course “this comes from me?”

Works of art are secret autobiographies. And perhaps literary works more than any others, because they are so explicit, so direct. They are not as symbolic, like music, for instance. It is also autobiographical, but so much more abstract. Literature is not at all abstract; it is very explicit, very concrete. It is an x-Ray of the human interior, human nature, the human condition; and one can be horrified at the monsters that emerge from within. But they have a cathartic function, and you are liberated from them at the same time.

It is a very healthy way to live. As an agnostic, where do you find the spirituality that religion brings to believers?

I think I find it in culture, in art, in literature. A kind of spirituality manifests therein. It is something that extracts from you that spiritual dimension that others only find in religion. But I believe that an agnostic does not necessarily have to be a materialist in the strictest sense of the word. You can live an intensely spiritual life through art, through culture, or through having a secular spirituality. Every agnostic has a certain anxiety when faced with that unconscionable thought of: “well, this is all there is, and when life ends all else ends”. It becomes extraordinarily strange and surprising like the idea of God, like the idea of life after death. It is very difficult, using only reason, to think of the afterlife, to think that there is another dimension…

Talking of the idea of death, how can literature fight against thoughts of death?

One of its extraordinary powers is that it allows us to live many lives. It takes us out of our reality and makes us live extraordinary realities, rich lives, adventures out of this world, makes us take on so many personalities, psychologies, mentalities… it is an extraordinary enrichment of life. However, at the same time, literature is not a guarantee of happiness; on the contrary, in some way, it renders you much more unhappy because it makes you understand there are many lives that are richer than your own. You become aware of your insignificance.

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

You have many childhood memories. Is childhood remembered or reconstructed?

Well, I think that one remembers in a relative way, because memory is very tricky, very selective. Memory erases or adds many things, because this helps you to live. I don’t think memory is absolutely objective, but I do believe that it is faithful to what you are, because even the transformations, the deformations that nostalgia or fantasy inflict upon memory are also a portrait of what you are, what you lack, what you would like to have but do not have… This exercise of memory, at least for a writer, is fundamental. In fact, Freud said that the years that form a personality can be found in childhood, in adolescence.

What has love meant in your life?

Love is, like literature, something that enriches life in an extraordinary way. I believe that it is difficult to communicate. Love is something that is lived in privacy. And that relationship, which is so intense –probably the richest relationship between human beings– at the same time requires great intimacy, requires a kind of confidentiality to be preserved, because when it becomes public it deteriorates, it becomes banal, does it not? But it is the most enriching experience there is. Everything is different when you live a great passion: things are better, everything is more beautiful, you face life with optimism, and only love gives you this. It is the fundamental experience, the most enriching and, at the same time, the source of great suffering, of course. Tragedies come from love, from unhappy love. The idealisation often made of the relationship often clashes with reality. But even so, I think no one would be willing to give up on love, despite being aware that love also has traumatic –sometimes terrible– consequences. But nobody gives up on it. Because to live that experience is to live the experience of all experiences. The fullest, the most intense, the most absolute.

And what is the meaning of love at your age?

I think that love has little to do with age. Well, the love of a young person is more idealistic, more innocent. The love of an adult, of an elderly person, naturally, is a love made up of lots of accumulated experiences, it is lived with more wisdom, with a better knowledge of reality. But aside from these differences, I believe that the elation, the joy, the feeling of optimism in life that love gives you is exactly the same as when you are a teenager.

Let’s speak of you book “The Civilisation of Spectacle”. Do you think that high culture no longer aspires to change the world?

Well, what I think is that high culture is disappearing. This, I believe, is an alarming tragedy –which is one of the reasons I wrote this essay– as high culture is, thus, naturally elitist. It is something reserved for a minority, and it is very naïve to think that high culture is accessible to everybody. Not everyone has the interest, the curiosity, the patience or the discipline that high culture demands.

On the other hand, the idea of culture being within reach of everyone is a good one. Who could possibly be against this? However, at the same time, if this means –and, unfortunately, in our time, it has led to this– that culture, in order to be accessible to all, needs to become trivialised, impoverished, and become but a pastime, a form of entertainment, then the result is clearly highly negative.

And I believe that this is a great flaw in the education of our time. The education of nowadays does not preserve high culture, but regards it with contempt. The art of creating or of thinking requires looking back into the past, because the present paints a fairly barren landscape in this regard.

Do you think that cybernetics have contributed to this desertification?

Without a doubt. Intellectual effort is gradually diminishing, because technology helps us give up making such an intellectual effort.

What role do you think intellectuals should play in current political life?

Look, I belong to a generation that was highly influenced by the ideas of existentialist thinkers. And although in many regards I have moved away from Sartre and am very critical of his work, I believe that his idea of the writer’s or the intellectual’s commitment to his time, to his reality, to his society, was absolutely correct. One cannot write, or paint, or compose by dispensing entirely with the problems of the world one lives in; and it is fundamental –particularly, if you believe in democracy– that everybody participates in the search for solutions to the problems: for answers to the great questions asked by society, in order to create a system where one can co-exist with all others, with one’s differences, ways of being, one’s own desires…

This is fundamental and, furthermore, I believe that true literature, true art, must address this situation. The main problem is that, nowadays, ideas are less important than image. I believe that pure technology is not enough and that the presence of ideas in public debate is paramount for our understanding of human issues. But in our time this seems to have been relegated and replaced by screens and pictures.

Because less effort is required.

It requires much less effort. But I don’t believe it should be this way, not at all. There is no historical law steering society in that direction. It is our decision. I think that, despite the importance of technology –this is undeniable–, it is necessary for ideas to continue to play a leading role in the life of societies, unless we wish to become a society of robots. I shall refer once again to Orwell, who was so insightful in imagining a world completely controlled by technology, a dictatorial world. Like The Republic of Plato, don’t you think?

Photo: Oscar del Pozo