British artist Glenn Brown (1966) himself acknowledges and admits the influence that French Post-Structuralist philosophy has had on both his thought and his works. Too much knowledge when contemplating a work of art can prevent the viewer from seeing and experiencing the emotional content of it, but this is counterbalanced by the great stimulus it poses for the mind. At a time when it is claimed that painting is dead, artists like Glenn Brown prove that it is very much alive. He uses a technique that bestows movement to the essence of the subject portrayed. It is as if, by breaking free from classical linear form, he opens the floodgates of its essence, stripping it from its static state and transforming it into an evolving entity. He takes over iconic works of other artists and transforms them.

Author: Elena Cué

Glenn Brown. Foto: Elena Cué

British artist Glenn Brown (1966) himself acknowledges and admits the influence that French Post-Structuralist philosophy has had on both his thought and his works. Too much knowledge when contemplating a work of art can prevent the viewer from seeing and experiencing the emotional content of it, but this is counterbalanced by the great stimulus it poses for the mind. At a time when it is claimed that painting is dead, artists like Glenn Brown prove that it is very much alive. He uses a technique that bestows movement to the essence of the subject portrayed. It is as if, by breaking free from classical linear form, he opens the floodgates of its essence, stripping it from its static state and transforming it into an evolving entity. He takes over iconic works of other artists and transforms them. He disassembles his images and presents them in a new way. The interconnection and dialogue with artists of the past help develop his own style and render his own interpretation. Opposites, humor, kitsch, even the pleasure of destruction and the fascination for the decomposition of the human form are also characteristic features of this artist.

We begin our conversation surrounded by his paintings in his London studio, where sculptures inspired in the intensity of Van Gogh’s palette will travel to his upcoming exhibition in Arles.

Is the interconnection and dialogue with artists from the past a condition to building your own style and offering your own interpretation?

Obviously, it’s only a one-way reaction. I can only take from them; I can’t give back to them as would happen with artists when they come into the studio. So obviously, artists from the past can’t comment on my work, I can only comment on theirs. But yes, just in the same way that my work is a combination of myself and all of my friends and the people who have helped me make the work, it’s also the case that it is a combination of all the artists that I’ve seen and learned from. And to that extent, you go back to Gilles Deleuze in terms of any individual being made up of the parts of the society that has constructed them. We are part of a rhizome, a structure of society that develops the language with which we think, as if we’re made of language. We can’t exist outside of it.

Where identities are lost and one is with many other...

I’m just trying to make it very clear that all artists borrow from the past and we cannot be wholly original, because to step outside of originality is to step outside of language. To be wholly original would be to be nonsensical. I think the idea of the avant-garde has made people believe that an artist is supposed to return to some childish level of communication, where the inner-self can be expressed directly onto a canvas and the raw emotion that is beyond language and beyond society will come out in some way. Expressionist painting was supposed to be that. Hence why artists like Picasso and de Kooning to some extent were making these thick, grotesque gestural paintings mimicking the work of children, as if they had the real understanding of what it was to be human. I borrow some of their work, as if to say, well yes, you’re partially right that the work of children is raw and interesting and describes something fundamental, but really what you’re doing is a pretence - it’s a game, because you’re being a very sophisticated artist using sophisticated color combinations and nobody really believes that it’s the work of a child. You’re just pretending, like an actor pretending to be somebody. I’m sort of contradicting the idea of the avant-garde, or trying to, which I think is still very prevalent in our understanding of what art is. It’s too dominant in society. Too much importance is given to the understanding of the real, and not enough importance to the idea that there is a shared understanding of society and that we are social beings more than anything else.

Glenn Brown. Led Zeppelin, 2005. Oil on panel. 122 x 86 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

Do you think then that style is produced by the forces from which thought springs?

To some extent, through my borrowing of artists as diverse as Gray or de Kooning or Rembrandt or Van Dyck, you could say I don’t know who I am myself, or that I have no particular style because I borrow so much from other people. I am partially saying that I don’t have an identity, I just choose.

Yet your work has its own distinct caracter that can immediately be attributed to you…

Precisely, because it is important as an artist, I think, to have an identity. Otherwise, nobody pays any attention. And although I’m saying it’s impossible to be original, I also believe that you have to try and be as original as possible and make objects that have never really existed before. So I am trying to make a painting that, although it’s based on somebody else’s work, you would never think was from the eighteenth or nineteenth century; it feels very twenty-first century and postmodern. I have particular styles of working, I mean the very flatness of the paintings and my obsession with the brush mark and the way that’s led into an obsession with the line and the movement that I try to create on the surface of the image, to make your eye slide around the image and continually feel that nothing is quite solid and everything is vaporous; sliding and moving and animated.

You said that you are not original and of course we are a combination of our pasts, but there is a tension between that and something in your thought process that can only ever be original.

That is the wonderful contradiction of making anything. You really want to present something and people like seeing new things; human beings are hardwired in their brains to want to see something new that they haven’t seen before. Something that is surprising and they can tell all their friends is different, and they now understand the world as being different to the way it was before. We love the idea of progression; that the human race is heading towards some nirvana where it becomes better all the time. I don’t believe that the world becomes better; I don’t believe that we become more intelligent. I just think things change - certainly in art. I can’t look at art from the Northern Renaissance – I’m thinking particularly of Dutch or German or Italian artists from the Renaissance. But I particularly like Northern European fifteenth and sixteenth century art. I really can’t think that art is better than it was four hundred years ago. I have Hendrick Goltzius’s etching over there of the Pietá, and I just can’t really conceive that art has ever got better than that, in depicting the idea of death and mortality and emotion and flesh and relationships and the way that the sky becomes electric with emotion. It almost predicts the idea of radiation in the work, or the idea that we are made up of atoms. There is something very atomized about that image.

You use a singular technique. With the movement that you imprint over the essence of the human being in your portraits, in order to break the linear way, do you intend for us to change our previous conception of understanding ourselves and the world?

The idea of the movement is that we are never fixed as individuals. Gilles Deleuze talks about the idea of the horse and the rider, and the rider, in understanding the horse, behaves like the horse. The horse behaves slightly like the human being because they both have to understand each other, in order for the rider to be able to ride the horse properly. They predict what each other are going to do, and are therefore joined together. There is a fluidity between the horse and the rider; between human beings and animals, just as there is when we have a conversation and we try to predict what the other person is going to say. Or we empathize with somebody else and that means there is a fluidity between one person and another. Brains almost literally become connected. That is why in a lot of the work, the linear form is trying to describe a literal fluidity - a melting, reforming or maybe rotting. The image decomposes, hence why I like painting flowers, because when they’re just at the point of being absolutely beautiful, they are about to die - cut flowers particularly, are already dead. They’re at the point in which they are at their most beautiful and we want to display them, but in order to display them, we have killed them. I love that contradiction of having to kill something in order to enjoy it. The important point is that the people and flowers and animals that I paint are maybe all appearing to be decomposing, but they are just transforming from one thing to another. The person rots away and then transforms into the soil, whose atoms then become part of the tree. Then an animal comes and eats the tree, and the tree becomes part of them. We all transform from one thing to another, we are all made of stars; the atoms that we’re made up of are billions of years old and once formed parts of stars. So it’s that idea that we are all eternal, to some extent. It doesn’t matter what form we take. We never truly die, we just transform continuously. I think that is also the essence of what it feels like to be human. I don’t feel as if I am absolutely aware of my skin the entire time, I’m not fully aware that I’m an isolated individual in the world. I feel like I’m part of the world, because I know what the street outside looks like and therefore part of my brain is out there in the street. I feel that I know what Russia is like, although I’ve never been there – so part of my brain is in Russia. I think to be human is to be fluid. It’s not to feel closed in. I’m trying to get at that idea of the inside and the outside, that the skin of the human being is translucent and things flow inside and outside. It’s as if the individual’s skin and flesh is turned inside out and we see the inner organs on the outside of somebody, or the musculature and the inner workings of the face all turned inside out, so that you start to see the structures that happen within the skin… I’m obsessed with that… the translucency of the flesh and the transmogrification of something turning from one thing into another. Andy Goldsworthy does that extremely well – the breaking down of one thing into another is done very beautifully, the way the line creates fluidity from one shape to another and then connects to each other. It is nothing original that I’m trying to do; artists have tried to do it for centuries.

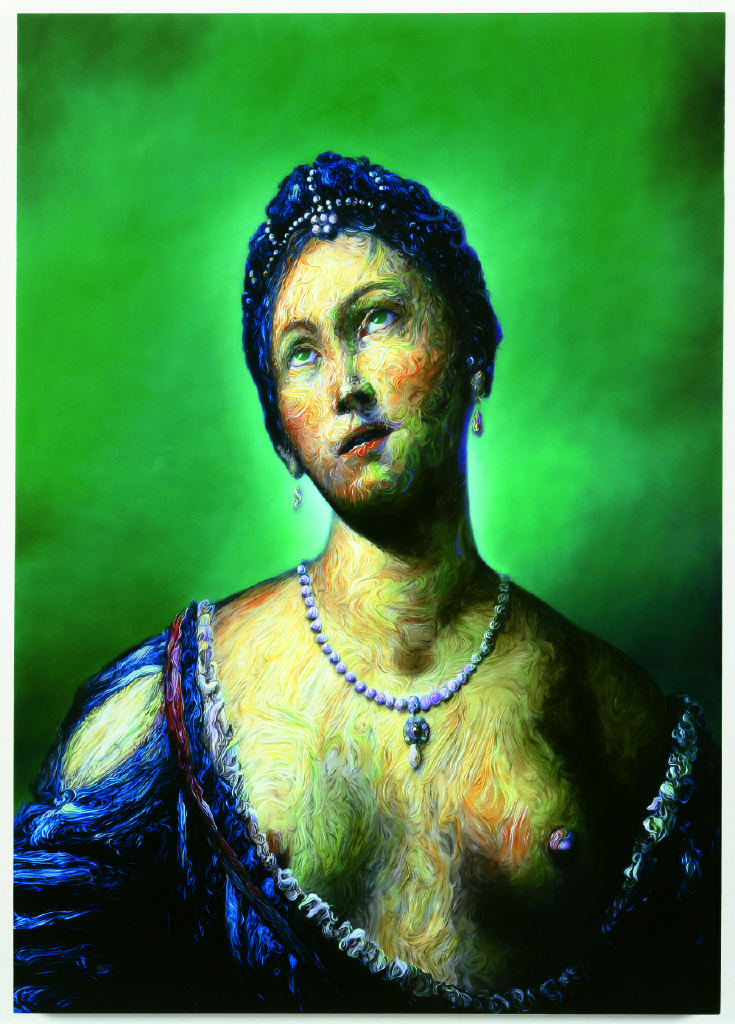

Glenn Brown. Reproduction, 2014. Oil on panel. 135 x 101 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

When you appropriate the paintings of other artists, what is your intent? To destruct and rebuild, or deconstruct and transform?

You do destroy, because it’s an act of homage to take somebody else’s work. People often ask whether I like the images that I work from, and I generally do, but not absolutely all the time. Sometimes they’re just paintings where the most important thing is what I can do to them, therefore I will see aspects of them without fundamentally necessarily needing to like the painting.

How do you choose?

It is something that I think I can transform. I see gaps in the work. It is a very disrespectful thing to do to another artist, to take their work and transform it, so it’s partially an act of homage and partially an act of destruction that I think I do. I’ve used a lot of the work of Frank Auerbach, and I like his work extremely, but I don’t think I could do what I do to his paintings if I wasn’t willing to say, well, I think maybe they don’t go far enough, I think maybe I can improve them… they don’t describe the world in the way I want it to be described, so it’s partially an act of criticism and partially an act of homage. I think it is like the relationship between the father and the son, or mother and daughter, where the two criticize each other immensely but they love each other. Families quarrel. Children want to rebel against their parents and tell their parents that they don’t know anything, that they misunderstand the world and that they know better. And all of those things are healthy, because fundamentally, we are our parents - they’re the biggest influence in our lives. So even though we rebel against them and hate them sometimes, they are us. It’s that same relationship of the parent and the offspring that I think I have with artists and art history. I love them and hate them in equal measure. To that end, when my father sees my work, he gets it immediately. He understands my work immediately. He’s my harshest critic, because he will sometimes see a painting of mine and say, you’re not trying hard enough with that one; you’re just trying to get away with it… you think you’ve done something that is good enough, but you can do better. He will point out bits that he doesn’t think works in them, and he is generally right as well. He knows the way my mind works. He is very helpful. It can be quite difficult sometimes, because he’s harsh… but good!

Opposites are very present in your work: figures between life and death, ugliness and beauty, opposite meanings of the paintings and their titles… Do opposites provide greater meaning?

They animate the painting. It is those strong emotions, when you see a film or you read a book and it takes you from a point of absolute elation to absolute disaster, and then back again to being elated. As human beings, we love to be told stories that make our heart beat faster and then calm us down. I don’t know fully why human beings like that; it gives us a sense of adventure, I suppose. I think as hunter-gatherers, we are hardwired to be interested in opposites because extremes can be very dangerous and we know we need to avoid them, very often. It all goes back to dreaming, as well. The reason we dream is to analyze all of the events that have happened in the previous day; to categorize them, to decide which are important and which we need to discard because it’s information we don’t need. It’s a sort of protection that goes back to hunter gathering. We want to know how the animal might behave, therefore we think, I need to think like an animal if I’m going to catch it. Again, going back to that fluidity of one thing flowing into another and the dream world being part of the actual world, and what differences there are between the two. You can’t really have a hierarchy; you can’t have the dream world without the real world.

Glenn Brown. Dark Star, 2003. Oil on panel. 100 x 75cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

The titles of your paintings are opposite to the meaning of the painting. What role does humor play in your work, so obviously present in the recycling of titles?

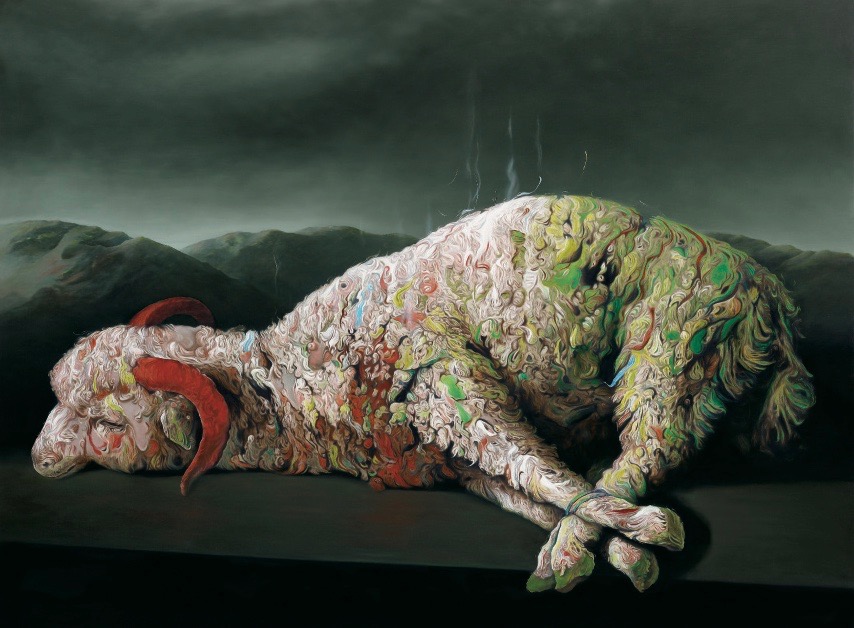

I like black humor… humor that is quite cruel. It appears to be nonsensical, but it’s about atomization basically, and it’s about the electricity between the couples. It is meant to be playing the game of having nothing to do with it, because there’s the idea of the human scale and the idea of the nuclear scale - which we perceive as either being very big or very small – with the human being in the middle. So there are opposites in scale within the idea of nuclear reaction. But it’s the electricity or the dynamism between the couples relating to the way they fight and argue with each other, yet love each other. And the way the marks are flying off, it’s as if the atoms are starting to break down and the radiation is destroying them. The idea of the destructive but creative power of radiation is in the work as well, because you don’t know whether the lines are flying off and breaking the figures apart, or whether everything is coalescing and forming back into itself again. There is a painting based on Zurbaran’s ram called Spearmint Rhino - it’s very big. Spearmint Rhino is a series of strip clubs, where women take their clothes off. And so you look at the picture of this ram, which appears to be decaying and smelling rather badly, wondering what this has to do with a lot of American strip clubs. And the ram is about entertainment. We have tied up the ram and killed it; it’s been sacrificed and killed for our entertainment. The reason we sacrifice things is illogical.

Glenn Brown. Spearmint Rhino, 2009. Oil on panel. 194 x 260.5 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

What meaning do you give color?

I do generally take color from other artists. I will look at books by Kees van Dongen or Van Gogh or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. But certain artists – especially those around the turn of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century – where they just tried their damndest to be as extreme as possible with color and really question what was possible, in terms of representing the world. And what happens if I make a painting where the sky is red, the trees are blue, the sea is purple and everything appears to be the exact opposite of what you’d expect it to be? But somehow by being the opposite, it doesn’t become unreal, it just becomes heightened reality, as if he is describing what is really there and we just haven’t seen it yet. I am just learning and stealing color from other artists, in order to try and heighten the theatricality of the real world. And not all of my paintings have very heightened color in them; for the last few years, I’ve been really concentrating on drawing, which has no color in it at all. Some of my paintings are black and white, where I’ll do the exact opposite, I’ll take all of the color out – or as much color as I possibly can – because even when you make a black and white painting, it’s never purely black and white. You get warm areas and cool areas. But I do like the way color describes emotion.

As a primarily figurative painter, how do you feel about the destruction of form, such as can be seen in your Auerbach-inspired paintings?

In a lot of the paintings, the original has become turned upside down, distorted and made abstract, in essence. You can’t recognize what I’ve painted anymore, though I have destroyed the original form and it’s been broken down into a surreal blob. There are a whole group of paintings that I call my blobby paintings, because they are not one thing. They appear to be renditions of a form, a blob, it’s at the point at which it could change into any one thing. You can’t really decide whether it is figurative or abstract, for instance, in a painting . But there are heads and figures you can see within it, so it’s at once both very figurative and very abstract as it transforms from one thing to the other. It has that fluidity of line, as though it is melting, or like chewing gum.

Glenn Brown. New Dawn Fades, 2000. Oil on panel. 71.5 x 62 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

What stimulates you more, knowing the world or helping others think through your art?

I like that question. It brings to mind the idea of which is more interesting: experiencing something or reading about it, for instance. Like a lot of people, I would probably say that I like the experience of reading about something. I like the second-hand enjoyment. For instance, I like looking at paintings and portraits, because I like traveling the world through art, in many ways. Especially in the way that painting allows you to travel through time. You can go to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries through paintings, in such a fantastic way. Not just because they’re literal renditions of what it was like to live in those centuries, but also how people felt in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is different to how they feel now. Their ideas of beauty, their ideas of pain and what death meant to them was incredibly different. People were surrounded by death and therefore I probably find the enjoyment of somebody else’s description of something slightly more interesting than actually being there. To travel to China and to go to the Great Wall of China is nice, but to read about it is much more interesting. I can only really appreciate the world through the stories told about it.