- Details

- Written by José Lázaro

Many are the creators who, throughout history, have believed they saw the origins of creativity, or at least some of its requirements, in good health and a feeling of wholeness. But neither are they few those who found the best stimuli for their creations to be suffering and sickness. Some seem to heed Horace’s advice to "delight and instruct"

Many are the creators who, throughout history, have believed they saw the origins of creativity, or at least some of its requirements, in good health and a feeling of wholeness. But neither are they few those who found the best stimuli for their creations to be suffering and sickness. Some seem to heed Horace’s advice to "delight and instruct" (or to create for one’s own delight) whilst others seem to confirm the saying "No pain, no gain" (or in this case, "No pain, no poems").

Not all authors of a theoretical or artistic work ascribe to one of these two opposing opinions regarding personal circumstances and, in particular, the moods that would stimulate their creativity and there are many who even reject the approach to the problem in those terms. But it is possible, however, to identify two clearly contending groups:

Of one school of thought would be those who consider that a state of well-being and satisfaction is the ideal one in order to be able to devote oneself to thought and artistic creation. This may seem the most obvious position since it coincides with the generally-held notion that culture is a luxury bestowed only on those whose most basic social, economic and psychological needs have already been met. However, the number of voices raised in protest against this viewpoint begs the question of whether this really is the majority view among creators.

Those of the opposing mindset maintain that discomfort, misery and anguish are the best fuel for creativity. Happiness is unproductive since it requires nothing whilst misery, on the other hand, would be a continuous spur to creative action, from this perspective. Creative work would serve as a means to expel the misfortune, thanks to one’s ability to express it creatively. At best, this intellectual or aesthetic expression of misery would enable us to overcome it, turning the manifestation of misfortune into a path leading towards well-being.

In his article "Duelo o placer de la escritura" (The Pain or Pleasure of Writing) (El País, 8 July 1986), the novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina argued both points of view. On the one hand, he recalled the beautiful words with which Cervantes described the ideal conditions for artistic creation: "Tranquility, peaceful surroundings, the pleasantness of the countryside, the serenity of the sky, the murmuring of the fountains and the stillness of the spirit in large measure turn even the most barren of muses fertile, offering new births to the world, filling it with wonder and contentment". On the other hand, Muñoz Molina broaches the idea of literary creation as the result of suffering, of the effort to flee from despair (and most definitely not as a gift from the sweet muses). Leaning towards the camp of those who think that human acts are more conditioned by historical circumstances than by the peculiarities of personal character, Muñoz Molina considered that these two outlooks would be characteristic of different times: "From Flaubert, perhaps from Baudelaire, the activity of literature, which was formerly a perk of laziness, shamelessly seeks the prestige of suffering and even of evil, which, on closer inspection, is a recent extravagance: among the Ancients, who admired Sophocles because he lived 90 years without a single day of unhappiness, the figure of Euripides, a hurdy and unhappy man mired in failure, was never emblematic of an artist but rather a mysterious exception".

The joyful laughter of the creator

The first viewpoint might be illustrated by the Nietzschean concept of creation. The creativity of the ‘higher self’ is, for this philosopher, a type of dance, a type of laughter, a type of game. The creator is the best representative of "great health": a being of joyful heart, of free spirit, light of foot. Fully convinced that "All good things laugh", the ‘higher self’ is able to laugh creatively because his theoretical works or his works of art are nothing more than the elaboration of that laughter with which he expresses his affirmation of the world; an affirmation that includes pleasure and pain, joy and misery and that is precisely why it is a tragic affirmation. For the Nietzschian creator, their work is the product of an unconditional affirmation of life, an affirmation that infuses them, that overflows from their eyes and hands; an affirmation understood as a desire for permanence, as a desire for eternity.

For Nietzsche, the antithesis of the creator is the priest – embodying the ultimate representation of all that is dirty, low and sick, of resentfulness triumphant over urges, of the weeping, wailing and gnashing of teeth, of the heavy heart, the gracelessness, of all that is sad, rigid and sterile. But included within this priestly archetype also belong all creators who feed off neurosis, anguish or pain and all those who require illness in order to be productive. From Nietzsche’s “great health”, it is noted with contempt that "Pain makes chickens and poets cackle".

This exciting concept of creativity, as proffered in some of Nietzsche’s theoretical texts, might seem to be called into question by the author’s own personal history: rejected by his university colleagues and by women like Lou Salomé, lonely, sick, isolated in rural boarding houses, writing books that nobody read, proud, misunderstood and ultimately committed to an asylum, Nietzsche does not seem to have been endowed with “great health”. And although all ad hominem arguments are usually considered dubious, the truth is that his life seems to be a denial of his joyful song. Unless we take it to mean that, as his works demonstrate, external personal circumstances failed to damage the energy of his laughter, the powerful dance of his thought, the great health of his spirit.

The artist's discomfort

The opposing approach has many advocates for whom creativity is nothing other than the philosopher’s stone, capable of turning suffering into gold. Art would be a happy encounter between anguish and the ability to express it beautifully. It would be elevated to the category of an author who, enduring the suffering produced by life’s difficulties, was able to do something of note with it. In this sense, neurosis would be the best resource of a fertile spirit, because, as in the words Borges put into his protagonist's mouth in “The Poet testifies to his Fame” - "the tools of my trade are humiliation and anguish".

There have been many artists who found a cause-and-effect relationship between misfortune and creation. "Ideas are substitutes for sorrows," said Marcel Proust. And Franz Schubert said that "Pain sharpens the spirit and makes the soul stronger". However, it is clear that pain can only have a toning effect if its nature, its intensity and the personality of the sufferer result in a fruitful response and not a sterile collapse. There can then arise an opposition between one pain that strengthens and another that sterilizes. Some think that it is a case of degrees: moderate pain would stimulate us, while excessive pain would paralyze us. As Émile Cioran has posited: "Great disasters offer up nothing, neither in the literary nor in the religious field. Only middling misfortunes are fruitful, because they can be, because they are a starting point, whilst a hell too perfect is almost as sterile as paradise".

Once the idea had been established that suffering was the source of creativity, its most ardent supporters began to draw conclusions. If discomfort is productive then everything that contributes to well-being probably has sterilizing side effects. For this reason, when a friend of the painter Edward Munch recommended he try to rid himself of the conflicts that were torturing him, he replied without hesitation: "They belong to me and to my art. They are part of me; if I were to remove them, it would harm my work. I want to hold on to these sufferings". And likewise, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke felt obliged to respond to an invitation of this kind: the aforementioned Lou Andreas Salomé, enthused by the work of Freud, recommended Rilke begin psychoanalysis in order to destroy the demons tormenting him. With suspicion akin to that of Munch, Rilke rejected the advice arguing that if psychoanalysis were able to wipe out his demons, it would also be able to destroy his angels. And then one is on the slippery slope to psychotherapists being sought out by authors with writers’ block, has-been painters and musicians in crisis who, having observed a clear relief from their neurotic troubles and an improvement of their mood but an impoverishment of their work, then demanded an urgent antidote against this cure.

There have also been authors who came to a reverse reasoning, stating that if pain and anguish are the stimuli for productivity, it is logical to think that pleasure and satisfaction are an obstacle to intellectual or artistic work. Borges, for example, recalls that "in a perfected paraphrasing of Boswell, Hudson references that many times throughout his life he had undertaken the study of metaphysics only for it to be always interrupted by happiness". If happiness is an obstacle to the study of metaphysics then simple pleasure can also be fatal for those faced with literary creation. Some have come up with an arithmetic formula for pleasures and creations according to which plus one pleasure equals minus one creation. And this is how one can interpret Balzac’s, albeit tongue-in-cheek, assertion that: "Every woman you sleep with is a novel you won’t write".

Along these lines, although with another type of argumentation, would be Freud’s stance: the artist would initially be so frustrated as to be bordering on neurosis. Like every other dissatisfied person, they would seek refuge in fantasies to compensate for their unfulfilled desires. What would allow them a release from frustration would be their ability to give expression to these fantasies and make them communicable by means of successful formal elaboration. Thanks to that skill, the secret imaginations of an introvert would potentially become works of art, able to provide pleasure to others and, as a consequence, able to provide its creator with success and with it the means to gratify their desires. The painful circle set in motion by dissatisfaction would thus be happily closed.

This Freudian approach could lead to the idea that in the artist’s past there would be someone (often a child) rejected and isolated by all others, or who at the very least would have the impression of being so. The psychogenesis of artistic creation would be linked to the need to overcome this state of loneliness, bitterness and lack of affection in which one’s character would harden and one’s intelligence, spirit and productivity sharpen. The suffering of the marginalized person would lead them to develop the qualities with which they will eventually achieve recognition from others, reunion and reconciliation with others and satisfaction through others. But from this odd theory, it seems to be being deduced once again that the consequences of a creator’s triumph would be the end of their creativity, that their success would essentially be castrating. And, although there are cases that confirm this idea, there are many others that refute it.

Creativity despite the bad, not thanks to it

In a lecture at the Madrid Circle of Fine Arts on 15 October 1987, the renowned English novelist Julian Barnes made some harsh criticisms of those who believe that suffering, illness and vice may be the origin of artistic creation. He instead vindicated the health of the artist in the face of the usual apologies for "the artists’ curse".

Barnes recalled that, for years, Flaubert collected newspaper clippings, quotes from articles or books and other similar materials that served as documentation. One of the folders in which he filed these was entitled "The stupidity of critics".

Among the texts he had kept there, Barnes found one about George Sand that seemed to him, effectively, "one of the most stupid criticisms that I have ever had the pleasure of reading". It attempts to explain the writer’s hostility to the family and to traditional, societal norms based on the fact that "George Sand smokes cigarettes all day, and George Sand is a woman!". Barnes commented that "George Sand’s cigarettes may have been responsible for many things, from an unpleasant smell in the salon to the cancer that killed her. But, as far as her opinions are concerned, the functioning of cause and effect is exactly the opposite of what the critic supposed. It was her opinions about women’s rights that led her to smoke, not smoking that shaped her opinions".

Barnes' criticism thus calls out all attempts to look for the origin of artistic creativity in factors that are ostensibly pathological and divorced from the talent and efforts of the artist: "At one time, doctors and philosophers would look for the location of the soul in human organs like the heart, the pituitary gland or wherever. Today we tend to locate genius in illness".

"What I attack, or at least what I am sceptical about, is this reductionist approach, the idea that the life of a writer or a painter can be explained in terms of a malady, a defect, a neurosis, of an incidence of sexual trauma in childhood or of smoking cigarettes. It is, incidentally, a trend that has been growing in the 20th century, partly, I suspect, due to the influence of psychoanalysis".

Barnes complains that, having published (by then) four novels, he had had to give several hundred interviews, leading him to ponder as to the reason for so many questions. "Perhaps interviewers are looking for that secret source of pain that would explain everything. But I can’t help them, I don’t think there’s anything to explain or at the very least I think my work is better explained in terms of my own work".

Among the many examples with which Barnes supports his position, he singles out a question that was posed to Gabriel García Marquez about whether the effusion of imagination and fantasy found in his books comes partly from pharmacological stimulants. Barnes acknowledges García Marquez’s right to show the interviewer the door but is glad that he gave the following answer instead: "Bad readers ask me if I take drugs when I write my books; but that just shows that they know nothing about either literature or drugs. To be a good writer, you have to be totally lucid at each and every moment and also be in good health".

After refuting, with historical and logical arguments, the theory that El Greco’s style stemmed from his hypothetical astigmatism, Barnes formulates his thesis in emphatic terms: "I am not saying that no painter has ever suffered from a sight disorder, nor am I saying that writers never smoke, drink alcohol, take drugs, suffer from diseases or behave neurotically. What I am saying is that they work despite all of this and not because of it. This century, we have almost made it orthodoxy that the artist is neurotic, sick or psychologically unbalanced. Of course, there are writers and artists who are paranoid but, in general, good writers and good painters rely on their ability to work really hard, their concentration and constant editing and revision until a certain perfection is achieved. And these are things that, in turn, depend on good health and a clean, clear mind".

Creativity notwithstanding the creator’s disposition

There is, therefore, a great diversity of opinion, reflecting very different and even exact opposite personal experiences. Finding an external point of reference to confirm or refute one or all others is no easy task. Some seriously defend the idea that sickness, misery and anguish, which turn the existence of the mediocre into pure torment, are instead, for creative minds, the stimulus and the essential instrument of their genius. Others argue that, for both an artist and a modest civil servant, malaise is merely an obstacle and a burden on one’s working or personal life.

There remains the option of rejecting the approach to the problem and criticizing the alternative on which revised opinions are based. There could be, at least in many cases, a separation between an artist’s work and their body or mind.

Assigning creativity its own autonomous character would lead one to think that works of art (or speculative constructions) cannot be reduced to the natural hazards of biology, to the disorders of the body or to the moods of the soul. But it is also possible to see in its genesis a total expression of the artist who, through amazing - and mysterious - mental mechanisms is able to transform what happens in the depths of his organism - and his mind - into an object of intellectual or aesthetic value. This alternative is so real that from it have derived two opposing ways of understanding aesthetics: the formalist and the psychobiographical. Neither is without merit and both have produced, in the hands of different critics, brilliant interpretations and utter nonsense.

José Lázaro

Professor of Medical Humanities, Department of Psychiatry, Universidad Autónoma of Madrid

Author: Vías paralelas. Vargas Llosa y Savater: un ensayo dialogado (Parallel Paths. Vargas Llosa and Savater: an essay in dialogues)

Translation from the original Dolor y goze en la creatividad in Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- The Pleasure and Pain of Creativity - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Pedro García Cuartango

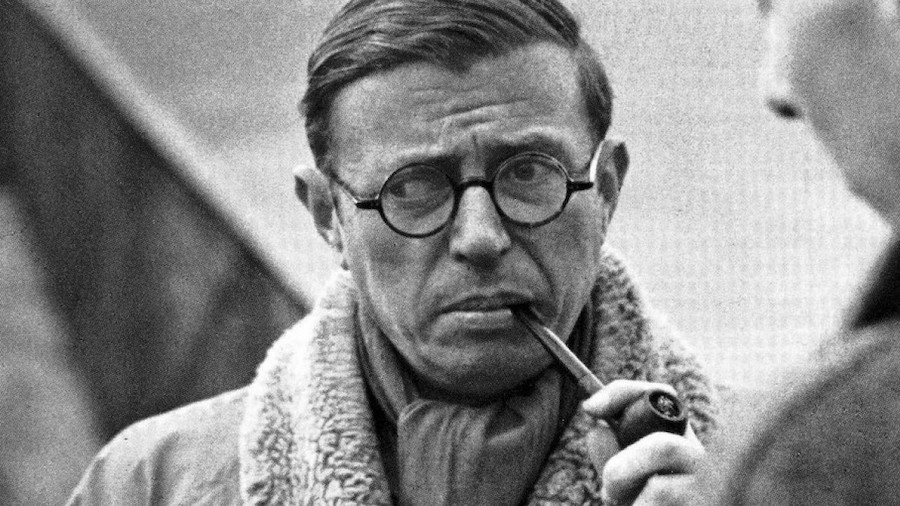

Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, argued that man lacks essence and is condemned to be free. Jean-Paul Sartre was a man of many parts: philosopher, novelist, playwright, literary critic and political agitator. But he was, above all else, someone who made the absolute most of a life that was intense.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, argued that man lacks essence and is condemned to be free.

Jean-Paul Sartre was a man of many parts: philosopher, novelist, playwright, literary critic and political agitator. But he was, above all else, someone who made the absolute most of a life that was intense. His open relationship with Simone de Beauvoir has passed into legend but Sartre, the most influential intellectual of his time, was also the father of existentialism and of a new way of looking at the world.

A French-born thinker, Sartre would become the icon of an era. There are photographs of him in basement jazz clubs with his friends Juliette Gréco and Boris Vian, standing on an oil drum haranguing Renault workers or selling the first copies of Liberation on the streets of Paris. Never without his trusty pipe, horn-rimmed glasses and roguish, irreverent air.

It would be difficult to summarize thoughts as prolific and diverse as his but if there is one book in which a systemization of his philosophy can be found, it is “Being and Nothingness”, conceived in the midst of World War II and published in 1943. Sartre, who served as a meteorologist, did time in several German prison camps after the defeat of France.

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Five years earlier, he had written "Nausea", a novel in which he laid the foundations of existentialism. Its protagonist is Antoine Roquentin, a bachelor living alone and working on the biography of an aristocrat. The book is a description of provincial city life where daily routines confront him with the absurd fact of existence. Roquentin says: “The essential thing is contingency. I mean that one cannot define existence as necessity. To exist is simply to be there.”

This phrase expresses Sartre's philosophy better than any other. The basic idea is that Man lacks essence, he is pure existence. We are not born with a specific nature nor are we part of a project. We are pure indeterminacy. We build our identity as we go, based on our actions.

Heavily influenced by his reading of Husserl, Sartre will go on to point out that consciousness is intentional, or in other words, it always indicates something. There is, as such, no self-awareness. What there is is a perception of others, through which we become aware of who we are.

As opposed to Hegel and Kant, Sartre argues that being is an appearance: it is what it seems or, better still, what it appears. But there is a being in-itself, which are things and the exterior world, and a being for-itself, which is the process through which the subject is built through the exercise of freedom.

As we as human beings harbour an emptiness within us (which Sartre calls nothingness), we are condemned to be free. This is the only determination with which we are born - the imperative to assume our own decisions. To exist is to choose. We must act according to our own rules.

In a few words that call to mind Kierkegaard, Sartre asserts that our anguish comes from the radical freedom with which we have been thrown into the world, from the need to choose between the multiple choices that present themselves at each and every moment. This exaltation of freedom is incompatible with the existence of God, which is a sublimation of reason. "Man is nothing but what he makes of himself," he says. For the same reason, Sartre turns away from both romanticism and psychoanalysis, which he considers a mythification of feelings.

More than an ethic, existentialism is an aesthetic that underlines the precariousness of man and the absurdity of existing. But it is still no less of a paradox that Sartre enjoyed life immensely with his love affairs, his fondness for alcohol, his sense of friendship and his travels.

From the 50s on, Sartre became increasingly politically radicalized, aligning himself with Maoism, Cuban socialism and, later, the May 68 movement. Although never a member of the Communist Party, he was a sympathiser on many causes, albeit always keeping his distance from Stalinism. In 1960, he wrote a controversial treatise entitled "Critique of Dialectical Reason" in which he attempted to liken existentialism to Marxism, an impossible endeavor.

Sartre's political shift pitted him against Albert Camus as both favoured opposing solutions to the Algerian War of Independence. The former sympathized with the rebellion against French colonization and the latter condemned the terrorism of the independence fighters and advocated for a political settlement. They would never be reconciled. There was no time to as Camus killed himself in 1960. Sartre would outlive him by two decades.

To his credit, it must be remembered that Sartre was never impervious to the great debates of his day. He was often seen at rallies, street protests and action in defence of minorities. He held his peace about nothing. He believed that the intellectual's obligation was to be present and to make heard a voice that still resonates with us today.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

Jean Paul Sartre on Intellectualism

Camus vs. Sartre

- Jean-Paul Sartre. To exist is to choose - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Leïla Slimani, born in 1981, is a French-Morrocan author and the 2016 winner of France's most prestigious award for literature, The Goncourt Prize, for her second novel, "Lullaby". In a distinctly French style, with a tone reminiscent of her compatriot Emmanuel Carrère, Slimani narrates, with both lightning rhythm and a sluggishness typical of day-to-day routine, a dizzying plot that leaves the reader in the uncomfortable position of being able to identify with these easily-relatable incidents. The reading of the novel is accelerated by the flow of her narrative in its search for what is hidden behind what we know to be fact from page one.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Leïla Slimani. Photo @ Heike Huslage-Koch

Leïla Slimani, born in 1981, is a French-Morrocan author and the 2016 winner of France's most prestigious award for literature, The Goncourt Prize, for her second novel, "Lullaby". In a distinctly French style, with a tone reminiscent of her compatriot Emmanuel Carrère, Slimani narrates, with both lightning rhythm and a sluggishness typical of day-to-day routine, a dizzying plot that leaves the reader in the uncomfortable position of being able to identify with these easily-relatable incidents. The reading of the novel is accelerated by the flow of her narrative in its search for what is hidden behind what we know to be fact from page one. Fiction and non-fiction intermingle in such a way that it becomes difficult to distinguish one from the other. The characters dance around the protagonist, a strange and unfathomable woman who lets only parts of her personality show so that the reader only forms an idea of her character gradually as the book progresses. Nothing is left to chance here. The characters are all intertwined up until their phobias and weaknesses are seen or perceived by others. With painstaking precision, she describes the atmosphere in the house, where most of the action develops, as if it were a discomfited witness to the suffocating reality within it.

Although having nothing in common with each other, the novel's "perfect nanny" Louise does bring to mind the figure of Vivian Maier, widely known as The Nanny Photographer - an enigmatic and solitary figure who spent her adolescence in France, returning to her American birthplace in the 50's, first New York and later Chicago, to work in childcare but never forgetting her true vocation - photography - and whose body of work, today internationally renowned, went undiscovered until after her death in 2009. She managed to the find a source of inspiration and gratification in the mundanity of her daily life, which she captured in thousands of photographic images that also served to alleviate whatever frustration she may have felt in an otherwise unrewarding job. The streets, with or without people, the children she took care of and her many ingenious self-portraits were captured in over 100,000 negatives, almost all of them recovered by the collector John Maloof. Some Super-8 films were also found along with audio recordings, all of which made Vivian Maier an exceptional chronicler of two American metropolises.

This digression helps us understand how little we know about the human condition and what remains hidden behind seemingly normal gestures and acts. Slimani shows us the enigma that underlies our subconscious and how, when one least expects it, it leaps ferociously into the wrong scenarios, thereby provoking incompehensible actions and reactions. The narrative manages to confuse the reader who is trying to make sense of what is irrational, what simple appearances don't reveal, what escapes our observation, the small details that describe to perfection the atmosphere breathed inside and outside the place of events. And it's a book that is hard to recommend to those mothers obliged to leave their children in a stranger's hands for many hours without really knowing what is going on in their home.

The novel pulls no punches when dealing with issues such as the female condition and the debate around motherhood versus career. The dilemma that exists between child-rearing and/or a professional life highlights the complexity of that choice. Parents justifying themselves and their dereliction of duty or priorities at any given time reflects the difficulty in deciding how to confront the situations we often find ourselves caught up in.

The novel was inspired by real-life events that took place in New York City in 2012.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Leïla Slimani: Lullaby (Chanson Douce) - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

Both among those who, by reason of their religion and culture, consider themselves to be Jews and for those living as Jews whilst also considering themselves an integral part of the secular and cosmoplitan mindset prevalent today, the question of a Jewish identity and the main issues involved in defining it is a recurrent one: for instance, the Jewish take on history and time, Jewish persepectives as regards individuality and collectivity, and, of course, anti-Semitism to name but a few. With the sole aim of contributing to the dialogue this type of reflection invites, I would dare to posit the two-way character, at once ambiguous and conflictual, of the Jewish estate that this conversation, broadly speaking, might well end up concluding.

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

Both among those who, by reason of their religion and culture, consider themselves to be Jews and for those living as Jews whilst also considering themselves an integral part of the secular and cosmoplitan mindset prevalent today, the question of a Jewish identity and the main issues involved in defining it is a recurrent one: for instance, the Jewish take on history and time, Jewish persepectives as regards individuality and collectivity, and, of course, anti-Semitism to name but a few. With the sole aim of contributing to the dialogue this type of reflection invites, I would dare to posit the two-way character, at once ambiguous and conflictual, of the Jewish estate that this conversation, broadly speaking, might well end up concluding.

I am referring, in particular, to that indeterminate oscillation, as yet unresolved but still so characteristic of the Jewish people, between the temptations of sectarianism and the impulse to participate in the dynamics of society on equal terms with the rest of its members. This seeming duplicity, this conflict or ambiguity in their position would be incomprehensible were we not to take into account the tenets of Judaism as a religion and the vicissitudes of concrete Jewish history up to the present. It will be a lay understanding of the specificity of religious tendencies and the mystical orientations of Judaism - which rewrite Judaistic history from a deep understanding of the reciprocal influences of religious, social and political factors - which can, to a large extent, shed light on the problems surrounding the situation of Jews in today's world.

Gershom Scholem, one of the greatest scholars of Abrahamic spirituality, pointed to messianism and redemption at the core of earliest Jewish belief as its defining elements, albeit as undertood very differently to the Christian view of them. Christianity sees redemption as an event that happens within the spiritual domain, invisible, inside the soul, in an individual's personal universe and one that refers, essentially, to an inner transformation that doesn't necessarily change the course of history, while for Judaism, the coming of the Messiah and the ultimate redemption are, essentially, an historic event that must needs take place both in the public arena and within the bosom of Jewish society. In other words, it is a visible, temporal happening that would be inconceivable without that outward manifestation. An internalised redemption interpretation has always seemed to Judaism a get-out clause, a loophole, an escape from the scrutiny and challenge that Messianism represents in terms of actively hoping for and, therefore, contributing to the restoration of creation to its original perfection.

But this state of active hoping and waiting is often at odds with a centuries-long evolution that spans everything from an optimism that fomented even large-scale socio-political revolutionary movements to an attitude of disillusionment - in no small measure determined by the failure of those very movements - in the midst of which the merely spiritual tends to prevail over the need for social and political action. It is at this moment that "the Hebraic political body stops functioning and its people withdraw from public life and history".

Scholem himself recognised, in this deep disillusionment with messianic hope, one of the major causes of the Jewish community's retreat inside itself, of its tendency to cloister and isolate and limit itself to just the conservation of its threatened identity and, perforce, of its political dismemberment. It is this situation that makes the Jew - and not just in the metaphysical sense of the clichéd "Wandering Jew" - a true symbol of the condition of every modern man and woman, as an individual deprived of community bonds, oblivious to true solidarity and dispossessed of a common homeland, as explained a few years ago by the French scholar and philosopher André Neher. According to Neher, the Jew is a voluntarily disenfranchised pariah who does not consent to being subjected to the worldly conventions that constitute a collective identity, but rather accepts their condition of marginality and becomes a conscientious pariah, even though this means renouncing the advantages of social success.

It is, perhaps, from this point of view of social marginalisation that one might best understand the Jewish approach to history, their exodus, their wandering, displacement and diasphora over the centuries. Judaism, according to Franz Rosenzweig, in so far as it positions itself outside both the course of history and the modern concept of history, imposes itself as the voice advocating the notion of itself as the measure and judge of all things. This does not mean to say that, in order to judge history, one has to be Jewish. However, it is the Jewish people who have demonstrated how it is possible to liberate not only themselves but Gentiles also from the weight of history, in as much as they do not wish to be part of it but, rather, to look at it in its entirety from the outside.

But if social marginalisation can result in an aptitude for historical critique, it can likewise induce behavioural patterns dominated by a desire to distinguish itself or to display qualities that speak to a, supposed or actual, Jewish superiority. This is what led figures such as Benjamin Disraeli to claim it a strategic virtuosity or an almost occult power over non-Jewish society which, both effectively and lamentably, served in its day to reinforce an anti-Jewish sentiment and anti-semitic prejudice. Instead of an objective judgement on the difference between Jew and Gentile, this attitude paved the way for simplistic, mytho-religious counterpositions and a manichaeism of good and evil. According to Hannah Arendt's detailed analysis of the social situation of Jews in pre-Nazi Europe in the first section of her The Origins Of Totalitarianism, it is the apoliticalism of Hebrew communities, together with the depoliticisation of the bourgeois masses, that contributed most to the rise of anti-semitism. Following on from Scholem, Arendt explains this illusory pretension to superiority felt by some emancipated Jews as one of the consequences of the bankruptcy of Messianic hopes and the Jewish secularisation that ensued. Judaism, once its spiritual and religious essence is diluted down, tends to transform itself into the mere fact of ethnic and linguistic belonging. Too "enlightened" to show any religious convictions, the emancipated Jew maintains, nonetheless, their links to the claim of belonging to the "chosen people" which places them outside both Jewish society proper and that of the Gentiles. The condition of this European Jew, within the vanishing framework of a bourgeoisie increasingly distant from its revolutionary origins, becomes almost elusive.

One way or another, the Jewish condition then takes on the aspect of a worldlessness or uprootedness. Lost in the secularised dream of heaven on earth, European Jews allow their political history to depend on external, casual and even sinister factors. And so ... does this not come to confirm the failure of the notion of politics not just in the Jewish world but in the modern world in general? Social particularism, obsession with prestige and the dissociation between citizenry and institutions are taken-as-read characteristics of contemporary Western society. However, all things considered, something positive has also come out of this failure, namely, that the distinction between a community's religious and political practices be built on the defence of a necessary distinction between the private and public spheres. Cultural traditions, ethnic and linguistic belonging or religious faith are what constitute the uniqueness of the actors on the world stage. But the chance for each of them to act freely in this world common to us all, whilst maintaining their differences from it, require an ability to transcend their unicity and singularity.

That is why a nation state like Israel, founded after the Holocaust in order for Jews to have their own political space, may seem regressive in the light of these modern world achievements and to the extent that it is based on strong confessional connotations. Perhaps the right direction to go in is not that of a search for a strictly nationalistic solution but rather, conversely, one that attempts to reconcile the specifically Jewish situation with that of society as a whole, one that tries to unite Jewish aspirations to emancipation with the right of all peoples to self-determination. In order for Jews to be liberated form their status as excluded and persecuted, it is necessary that they be themselves, in any public sphere, and that they be equal to non-Jews, assuming and themselves demanding equality with all others. They will, of course, still need to maintain their own historical, religious and cultural identity. As Emmanuel Levinas rightly observed, Judaism is the face of an exteriority that cannot be engulfed in an undifferentiated entirety. But they must also transcend this identity and move towards a structure of universal relations. Only by acting independently of their ethnic origin or religious faith can Jews acquire the right of access to that common public domain in which the status of plurality becomes reality, or, in other words, where they can live as distinct and unique beings among their equals.

In a nutshell, the Jewish condition, having now become a symbol of modern exile and rootlessness, would then assume the fundamental significance of a struggle for the conquest not just of a physical or a social space but, more importantly, of a political one. A space where the irreductable, entrenched differences between people based on their origins no longer constitute a factor in discrimination but become, rather, the foundation for the equal and pluralistic participation of all in the practice of politics.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- But just who are the Jewish people? - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

It is highly likely that, for many people, philosophy ultimately amounts to nothing more than an ambiguous word, used as it is in very varied contexts to refer to different things. As a common linguistic expression, the word "philosophy" doesn't have a precise substance to it and nor does it allow for a generally accepted or acceptable brief definition. We hear repeatedly about the philosophy of an electoral programme in politics or the philosophy of a marketing strategy for a product in the fields of commerce or industry. We also hear it said, in our everyday language, that it is best to look at life philosophically or that each person has their own philosophy on life. Lastly, it is said that philosophy is also a type of knowledge, somewhat vague or even obscure for some, engaged in or indulged in by certain individuals not unknown for a certain smugness and distinguishable by their aura of esotericism and mystery.

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

It is highly likely that, for many people, philosophy ultimately amounts to nothing more than an ambiguous word, used as it is in very varied contexts to refer to different things. As a common linguistic expression, the word "philosophy" doesn't have a precise substance to it and nor does it allow for a generally accepted or acceptable brief definition. We hear repeatedly about the philosophy of an electoral programme in politics or the philosophy of a marketing strategy for a product in the fields of commerce or industry. We also hear it said, in our everyday language, that it is best to look at life philosophically or that each person has their own philosophy on life. Lastly, it is said that philosophy is also a type of knowledge, somewhat vague or even obscure for some, engaged in or indulged in by certain individuals not unknown for a certain smugness and distinguishable by their aura of esotericism and mystery.

The fact of the matter is, especially for those who have not yet taken a serious, personal interest in philosophy as an intellectual discipline, that whatever common denominator, if any, there might be amongst the multiplicity of applications of the term "philosophy" and its concepts, this has not made itself widely known. Even granting that differentiating between philosophy as a vital attitude and philosophy as theoretical knowledge, let me focus, for now, on the latter meaning whilst acknowledging that the complexity and difficulties in reaching a clear and precise concept of what philosophy actually is will persist. One might be able to see things more clearly by making a comparison.

If we ask ourselves what biology, mathematics and history are as intellectual disciplines and what they are used for or why they exist, defining them is not an insoluble problem. Thus, biology is essentially the study of living matter and organic phenomena, using the observational method. Its results are useful in the fields of medicine, industry, agriculture, etc. There is no special difficulty in answering the question "What is biology?" But is it the same in the case of philosophy, even when understood as just an intellectual discipline? Even after 27 centuries in existence, anyone would be hard pushed to provide such a clear answer to the questions: "What is the purpose of philosophy?" or "What is the reasoning behind this age-old intellectual pursuit?"

Perhaps someone reading this might be expecting me to reveal the "right" concept of what philosophy is, to resolve all the confusion and to provide a magical answer that would eliminate any doubt. Forgive me for telling you that I don't intend to even try. And not just on the hackneyed pretext that it's not possible to solve such a complex and thorny issue in the short space of an article but because I consider myself highly unlikely to succeed at an endeavour where many illustrious teachers have failed before me.

Given the changes that the concept of philosophy has undergone throughout history, along with the breadth and variety of cultural products that have designated themselves "philosophy", it becomes very difficult and risky to construct or to coin a univocal, definitive and universal concept of what philosophy is. The formulation of its tasks and objectives has been modified according to historical circumstances and as each particular science has appeared and evolved. Which is why, from a systematic point of view, it isn't entirely possible to determine philosophy's scope of study, objectives and methods with any set know-how or science and in the established way, from the word go. The defining characteristic of philosophy as an intellectual discipline is, therefore, going to be the crux of its task in having to "critically" justify itself in the selfsame way that reason develops in its attempt to understand the world.

In very general terms, the vast majority of the great philosophers of the past constructed their philosophies from a specific "modus operandi", or rather from a certain "method" that distinguished philosophy from other fields of knowledge, particularly the sciences. Thus, while each individual science was concerned with one given and fixed objective or with the one specific problem that constituted its speciality, be it organic phenomena in the case of biology for instance, or the study of fossils in that of paleontology, or atmospheric phenomena in that of meteorology, philosophy's "speciality" was, one could say, "the totality of what is", or in other words, the sense of the whole, the being of the universe, taking universe to mean the whole, integral ensemble of everything that is, of the universals that exist within it and their mutual relationships.

Methodologically, our philosopher was not (strictly speaking) interested as such in each and every object or problem that makes up the universe in themselves, in their separateness and specificity but rather in the sense of their interrelationships, what each thing "is" together with or in opposition to the rest, its position, role and rank in the grand scheme of things and what each thing represents in the entirety of universal existence. The scientist, bound by the self-imposed constraints of his method, has always positioned himself within the universe, marking off a portion of it with what he has made the object of his study. But, in so doing, he automatically broke the web of interdependencies in which every object cannot help but find itself, blocking out the integrity of our lived world as it appears to us inside our natural and spontaneous mindset. This is precisely what the philosopher was therefore looking for: a totality, an idea, an all-encompassing conception of the whole or of this innately-sensed universe in which we go about our daily lives, not as a jumbled, bitty mess of things but as something complete and unified.

Perhaps at first glance, these aspirations and attempts by past philosophers to think of the sense of the whole as a systematic and unified conception of all reality might seem, to those of us in the 21st century, to have something of the megalomaniac about them. In fact, these days, such an undertaking is still considered to be an illusory task of impossible and unbridled pretensions even though, granted that it seeks to find a sense of the whole of the universe and of life, philosophy is just a discipline that is neither more nor less modest than any other. Because that Whole, so sought-after by philosophy, was not thought of as a numerical set of existing things, nor was it made up of the sum of all knowledge from all the sciences. Rather, it would confine itself to pursuing the universal in each and every thing, its essence, the factor that makes every object connect with and fit into a totality, thus acquiring a fullness of meaning.

Hegel - surely the last of the great systematic and metaphysical philosophers - said that only philosophy made us see the world as it is, as a whole, and not illusively as the separate things that might appear in it; isolated, autonomous, unrelated, meaningless. As opposed to the sciences, philosophy would thus have a role of the highest order to fulfil and that would be none other than to offer a concept of the whole, a "metaphysical" notion of the beingness of the world and the meaning of life.

One of the arguments put forward by contemporary critics of this metaphysical philosophy of the past has been that, if the validity of a knowledge is measured by the effective results obtained in whatever subject it addresses, then philosophy's progress over its 27 centuries of existence and endeavour does not seem to have achieved anything at all effective and almost nothing close to what it claimed to be researching. Because, where is this progress? Who today possesses this unified and universal concept of the sense of the whole of the Universe that is more or less commonly accepted? What is this concept of the world itself that philosophy presents to humanity today? What are the core values that philosophy proposes in order to morally orient the actions and lives of men and women today?

The answers to these questions do not allow for any one consensus of opinion on the systematic achievements of past philosophers regarding philosophy as the "science of knowledge", or an intellectual discipline. For precisely this reason, the only possible answer today to the question "What is philosophy" should start with a refusal to distinguish philosophy as intellectual discipline from philosophy as an attitude to life. Philosophy is and remains, first and foremost, that - an attitude, an outlook, man's way of existing as he confronts the world. But it is an attitude that takes the form of aspiration, desire, restlessness, anxiety, and a "desire to know", to understand, to appropriate wisdom. And this is precisely what the term "philosophy" means in ancient Greek - "the love of knowledge". However, as a quest for a general sense of the world and for reasons that guide our behaviour and our expectations, it cannot, strictly-speaking, claim any definitive theory of anything. Instead, it probes and analyses in an exhausting search for itself and in the continual pursuit of the multiple, changing meanings of things. And even more so given that the world, society, human behaviour and life taken altogether are not static. They are, rather, living entities in a progressive and integral state of flux covering an infinity of dynamic interrelations.

Even so, there will still be someone asking, and they would be perfectly in keeping with the pragmatic and utilitarian spirit of our times: "What is philosophy for?"; "Which of our needs does it satisfy?"; "Why all this searching for meanings and the value of phenomena and processes that the sciences are already dealing with better and more rigorously?"; "Why not just do what the vast majority of people do which is just live their lives in peace, ignoring all the vagueness and ambiguity that philosophers tell us about?"; or "Perhaps there's more to all that searching than just a subtle way of complicating our lives and most definitely everyone else's as well?"

Kant said that whoever philosophises does so at the insistence of his own reasoning's dynamism. In other words, his mind will not be pacified with any old explanation, aspiring, rather, onwards and upwards in search of supreme syntheses and the most penetrating, all-encompassing meanings. Aristotle, for his part, thought that every human being, in one way or other, is a philosopher by nature because, in his view, every human being wants to know. And Plato asserted that when this desire for knowledge and this love of wisdom (which are the essences of philosophy) happen to someone, stirring and awakening in them, then it is usually as a result of that person's painful, prior realisation that they don't know, that they don't understand and that they "need" to know in order to be. It would, therefore, be in that perception of one's own ignorance and "lackingness" that the root of knowledge, and hence philosophy, lies.

And it is because of this deficiency and fundamental powerlessness that every man and woman, in order to be a human being, is forced into repeated attempts to ascend from their innate ignorance towards wisdom, an effort that can only be beneficial and productive when it is as a result of a love of knowing. Or, put differently, when it comes from an outlook on life that can be described unequivocally as philosophy, a probing attitude arising from the human need to understand and express itself. It can thus be seen how this vital attitude underlying philosophical activity comes to symbolise and essencialize its educational and autodidactic function since, due to its methodological stance, philosophy insists on the absolute requirement to always go above and beyond the mere accumulation and superimposing of specialised, partial or disjointed information, like that provided by each of the individual sciences. In other words, it advocates, as its most defining feature, the need to arrive at a meaning that somehow includes the interrelationships between and the places that different partial and specialised knowledges should occupy in an ideal universal synthesis, something that would be neither attainable nor formulatable in a closed system, of the type of knowing that would reflect, in an achievable way, the totality of all that it is possible to know.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

"The most intelligent and most important poet our country has produced this century has died, in hospital in Rome, as a result of the burns she suffered, apparently, at home in her bath according to the Italian authorities' investigations. I have travelled with her and during our travels, she shared many of her philosophical opinions as well as her concerns about the way the world was heading and about the course of history, both of which frightened her throughout her whole life." With these words, Thomas Bernhard summed up the death of his dear friend, Ingeborg Bachmann. Bachmann died on the 5th May 1973 of burns sustained during a fire at her house in Rome. She had chosen to settle there definitively in 1969 for its Southern European warmth and sunlight.

|

Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

"The most intelligent and most important poet our country has produced this century has died, in hospital in Rome, as a result of the burns she suffered, apparently, at home in her bath according to the Italian authorities' investigations. I have travelled with her and during our travels, she shared many of her philosophical opinions as well as her concerns about the way the world was heading and about the course of history, both of which frightened her throughout her whole life." With these words, Thomas Bernhard summed up the death of his dear friend, Ingeborg Bachmann.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Three Paths To The Lake by Ingeborg Bachmann - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

|

Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Photo from the archives of Svetlana Alexievich

Svetlana Alexievich (1948, The Ukraine) was last year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature on one of the very few occasions it has been awarded for a work of non-fiction or in her native language, Russian. Only Theodor Mommsen, Winston Churchill and Solzhenitsyn have ever been likewise honoured for historical research in prose.

Front covers of the English and Spanish translations of Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel Prize-winning book

It is throughout her book, War’s Unwomanly Face, that the characters’ transcribed voices denounce some of the worst crises of the twentieth century, as experienced by the then Soviet Union: the Second World War, the Afghan conflict, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. Alexievich has invented a new literary genre in which the reader inadvertently comes face to face with gritty truths spoken from the deepest wells of pain in the human soul.

The style of War’s Unwomanly Face is arguably and essentially that of a doctoral thesis documenting the behaviour of Soviet women on and off the battlefield during the Second World War. The book is made up of the not-so-fond reminiscences and short personal stories told to the author by women who risked their lives for their country but were never credited, or even remembered, by history until now. Alexievich remembers how, as a child, she would listen enthralled to the women in her village swap tales about the war. They and their stories had a huge impact on her young mind that only increased over time and led to her wanting to find out more. After moving to Belarus in the late 1960’s to study journalism and forging a highly successful career there, Alexievich embarked on a journey to interview hundreds upon hundreds of women who had served in the Red Army. Those monologues became the initial stages of what would turn out to be a rich and detailed tapestry of testimonials concerning the role and vision of women during this terrible period of time in modern-day history. Women who survived and lived to tell the tale of circumstances so extreme, tragic and painful that it is difficult for us to hear, let alone imagine, them in today’s world. All of these lived experiences, recounted from the most intimate memories of the female protagonists, make up a choral narrative with a unique perspective – what the war to combat a German invasion meant for Russian women at that time and what they understood by patriotism. The author, whilst remaining true to the serious revelations contained in every memory she records, does also grant the reader frequent respite from the severity of her subject matter by the inclusion of seemingly frivolous little anecdotes from the humdrum everyday lives, even during wartime, of otherwise unremarkable human beings. Her prose is concise and without artifice, thereby brilliantly resolving the difficulties inherent in dealing with feelings. It also transmits the author’s empathy with her interviewees who leave us in no doubt as to the veracity of their testimonies and who imbibe the entire book with their palpable strength of will.

World War II female Soviet snipers. Photographer unknown.

The publication in 1985 of War’s Unwomanly Face, written two years earlier, coincided with the welcome arrival of the perestroika/glasnost era and was met with spectacular critical acclaim and commercial success. Its 2015 publication in Spain came in the same year it was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

This is evidently not, therefore, just another book about war or the barbarity of war in our time. It is, rather, a reflexion on the hopes invested in and frustrated by the events that constitute our recent history. When, in 1979, Lyotard described a crisis facing longer novels versus the proliferation of shorter books whose infinite varieties are unforgiving of them, he could have been describing exactly what Alexievich does on a daily basis, namely: she maintains the individual identity of each of her speakers without compromising their credibility or that of the narrative.

For me to recommend that you read it smacks almost of a dare because, as Franz Kafka once said, this is a book that deserves your attention and one that will strike you down with the aim of an ice-pick, chipping away at the coldness in your heart, mind and very spirit itself.

World War II sniper Roza Shanina with her rifle, 1944. Photo by A. N. Fridlyanski

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- “War’s Unwomanly Face”. Svetlana Alexievich - - Alejandra de Argos -