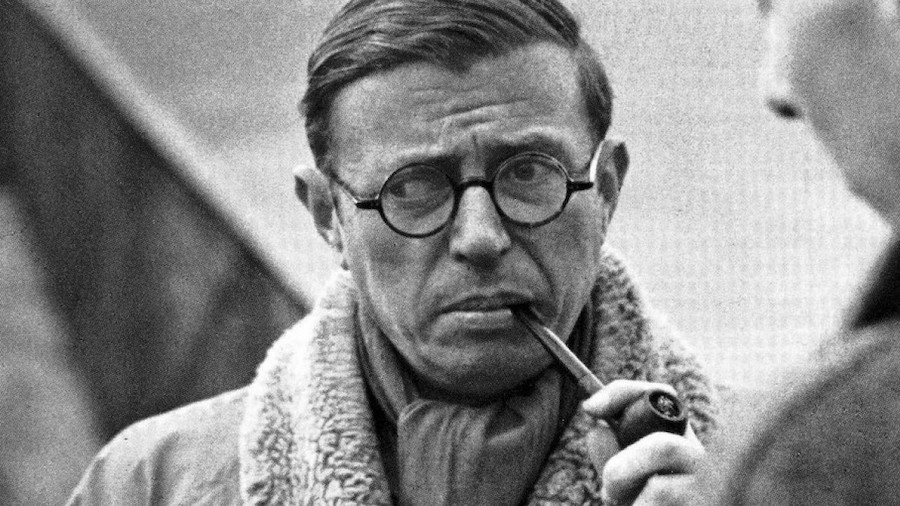

Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, argued that man lacks essence and is condemned to be free. Jean-Paul Sartre was a man of many parts: philosopher, novelist, playwright, literary critic and political agitator. But he was, above all else, someone who made the absolute most of a life that was intense.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, argued that man lacks essence and is condemned to be free.

Jean-Paul Sartre was a man of many parts: philosopher, novelist, playwright, literary critic and political agitator. But he was, above all else, someone who made the absolute most of a life that was intense. His open relationship with Simone de Beauvoir has passed into legend but Sartre, the most influential intellectual of his time, was also the father of existentialism and of a new way of looking at the world.

A French-born thinker, Sartre would become the icon of an era. There are photographs of him in basement jazz clubs with his friends Juliette Gréco and Boris Vian, standing on an oil drum haranguing Renault workers or selling the first copies of Liberation on the streets of Paris. Never without his trusty pipe, horn-rimmed glasses and roguish, irreverent air.

It would be difficult to summarize thoughts as prolific and diverse as his but if there is one book in which a systemization of his philosophy can be found, it is “Being and Nothingness”, conceived in the midst of World War II and published in 1943. Sartre, who served as a meteorologist, did time in several German prison camps after the defeat of France.

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Five years earlier, he had written "Nausea", a novel in which he laid the foundations of existentialism. Its protagonist is Antoine Roquentin, a bachelor living alone and working on the biography of an aristocrat. The book is a description of provincial city life where daily routines confront him with the absurd fact of existence. Roquentin says: “The essential thing is contingency. I mean that one cannot define existence as necessity. To exist is simply to be there.”

This phrase expresses Sartre's philosophy better than any other. The basic idea is that Man lacks essence, he is pure existence. We are not born with a specific nature nor are we part of a project. We are pure indeterminacy. We build our identity as we go, based on our actions.

Heavily influenced by his reading of Husserl, Sartre will go on to point out that consciousness is intentional, or in other words, it always indicates something. There is, as such, no self-awareness. What there is is a perception of others, through which we become aware of who we are.

As opposed to Hegel and Kant, Sartre argues that being is an appearance: it is what it seems or, better still, what it appears. But there is a being in-itself, which are things and the exterior world, and a being for-itself, which is the process through which the subject is built through the exercise of freedom.

As we as human beings harbour an emptiness within us (which Sartre calls nothingness), we are condemned to be free. This is the only determination with which we are born - the imperative to assume our own decisions. To exist is to choose. We must act according to our own rules.

In a few words that call to mind Kierkegaard, Sartre asserts that our anguish comes from the radical freedom with which we have been thrown into the world, from the need to choose between the multiple choices that present themselves at each and every moment. This exaltation of freedom is incompatible with the existence of God, which is a sublimation of reason. "Man is nothing but what he makes of himself," he says. For the same reason, Sartre turns away from both romanticism and psychoanalysis, which he considers a mythification of feelings.

More than an ethic, existentialism is an aesthetic that underlines the precariousness of man and the absurdity of existing. But it is still no less of a paradox that Sartre enjoyed life immensely with his love affairs, his fondness for alcohol, his sense of friendship and his travels.

From the 50s on, Sartre became increasingly politically radicalized, aligning himself with Maoism, Cuban socialism and, later, the May 68 movement. Although never a member of the Communist Party, he was a sympathiser on many causes, albeit always keeping his distance from Stalinism. In 1960, he wrote a controversial treatise entitled "Critique of Dialectical Reason" in which he attempted to liken existentialism to Marxism, an impossible endeavor.

Sartre's political shift pitted him against Albert Camus as both favoured opposing solutions to the Algerian War of Independence. The former sympathized with the rebellion against French colonization and the latter condemned the terrorism of the independence fighters and advocated for a political settlement. They would never be reconciled. There was no time to as Camus killed himself in 1960. Sartre would outlive him by two decades.

To his credit, it must be remembered that Sartre was never impervious to the great debates of his day. He was often seen at rallies, street protests and action in defence of minorities. He held his peace about nothing. He believed that the intellectual's obligation was to be present and to make heard a voice that still resonates with us today.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

Jean Paul Sartre on Intellectualism

Camus vs. Sartre

- Jean-Paul Sartre. To exist is to choose - - Alejandra de Argos -