Long after her death, Frida Kahlo has ultimately transcended her own reality. From revolutionary painter, creator of intimate worlds and a woman tortured and wronged but also open to love, her public image has since become that of a veritable icon, perhaps even to the point of tipping over into a dangerous banality. But the millions of images of the artist that have become merchandising do not in any way detract from the enormous power of her work.

Art with wings to fly

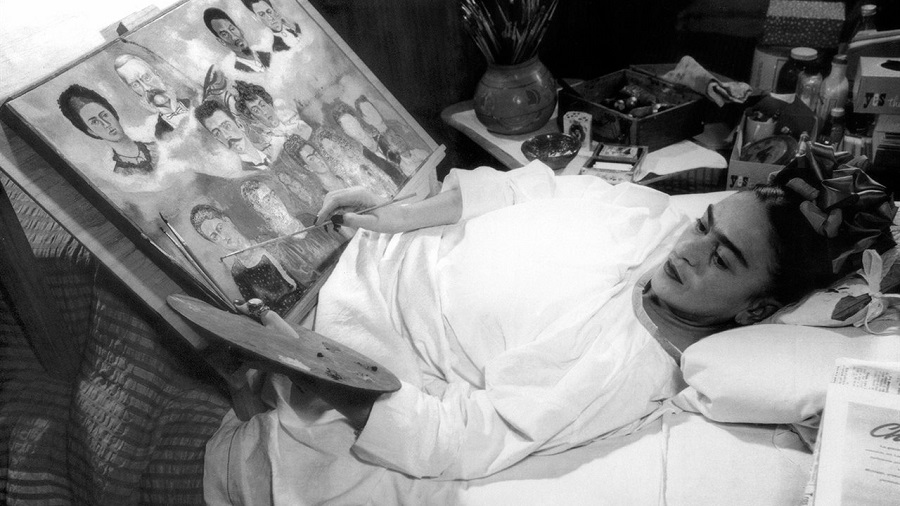

Frida Kahlo painting “Portrait of Frida's Family”. Photo: Juan Guzmán,1950-51 from www.historia.nationalgeographic.com.es

Long after her death, Frida Kahlo has ultimately transcended her own reality. From revolutionary painter, creator of intimate worlds and a woman tortured and wronged but also open to love, her public image has since become that of a veritable icon, perhaps even to the point of tipping over into a dangerous banality. But the millions of images of the artist that have become merchandising do not in any way detract from the enormous power of her work. Kahlo's potential and talent flourished through sickness, suffering and prostration. In her own words, "Everything can be beautiful, even the worst horror". She was also able to turn herself into works of art with their own entities, following in the wake of other artists such as Salvador Dalí.

Rooted in her own culture and a lover of beauty (her own and others’, within and without), Kahlo’s image and persona enjoy actual cult status in Mexican society, where portraits of her even take pride of place in altar places dedicated to other saints. In life, Kahlo was faced with a terrible reality and used art to show her suffering, overcome it and learn to live with it. And she did not have far to go in order to create her own personal imaginary, so admired by artists like André Breton, saying "I never paint dreams or nightmares. I just paint my own reality."

Childhood, apprenticeship and tragedy. The early years.

Magdalena del Carmen Frida Kahlo was born in the famous Casa Azul (The Blue House) in Coyoacán, Mexico City, in 1907. Her father, Guilermo Kahlo, had emigrated to Mexico from Germany in 1890, at the age of 19. Frida was the third of four children to Matilde Calderón, Guilermo’s second wife, the first, with whom he had had two other daughters, having died in 1884. In her early childhood, the budding artist lived a life of luxury, resulting from her father's profession as a jeweler to Mexican high society and his work as a photographer, which he took up after his second marriage. However, after the end of Porfirio Díaz's rule (known as "The Porfiriato"), the family began to experience serious money problems.

La Casa Azul, now the Frida Kahlo Museum

In 1913 and at the age of six, Frida was diagnosed with polio and bedbound for 13 months, her first contact with the disease which was to become a permanent shadow throughout her life. Although she managed to recover and despite her right leg being seriously deformed, as a little girl she was already showing early signs of her ability to overcome adversity and began assisting her father in his work, participating in tasks such as developing, retouching or taking photographs. This collaboration was her first, and a fundamental, contact with art.

In 1922, Kahlo enters the National Preparatory School where she comes into contact with the most progressive ideas of her time. Intelligence and talent are her best defense against the taunts occasioned by her limp but her forceful personality wins out and she becomes a member of the group ‘Los cachuchas’, where she meets her first boyfriend, Alejandro Gómez Arias. In 1925, the bus on which they were both travelling collides with a tram. The accident causes Frida multiple fractures throughout her body and greatly exacerbates the poliomyelitis in her right leg.

Painting as salvation and a means of expression

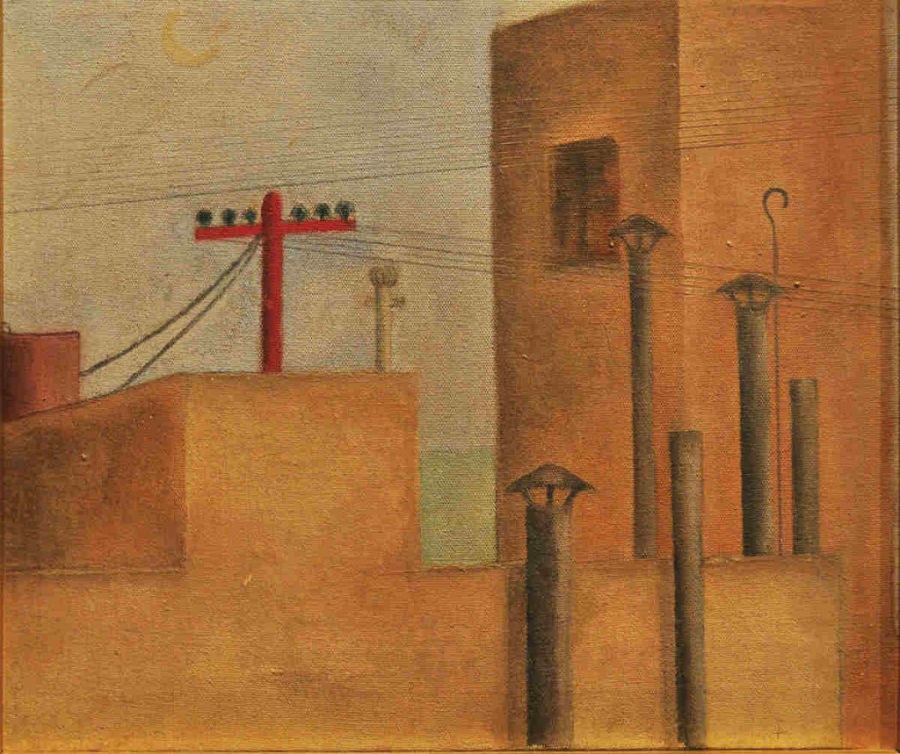

“Urban Landscape”, circa 1925. From arquine.com

Bedridden, her father gifts her a box of paints and brushes. It is the beginning of her unbridled passion for the art that would be her companion throughout countless periods of prostration and serve as psychological alleviation from the constant pain that would never leave her while she lived. As Frida herself described it, she began painting in bed "with a plaster corset that went from the collarbone to the pelvis", with the help of "a very funny device" - an angled contraption devised by her mother to support a stiff board and paper.

In one of her earliest works, "Urban Landscape" (circa 1925), some of what would become constants in her pictorial trajectory were already discernible. Painting was not an end in itself but a means by which to explore reality and portray a series of sensations. The landscape, anodyne and austere, is not of the utmost importance. According to the writer and biographer Araceli Rico, the work shows a space that is "narrow, reduced to inconceivable dimensions [...], a small theatre staging her own life".

Exploring her identity. Self-portraits

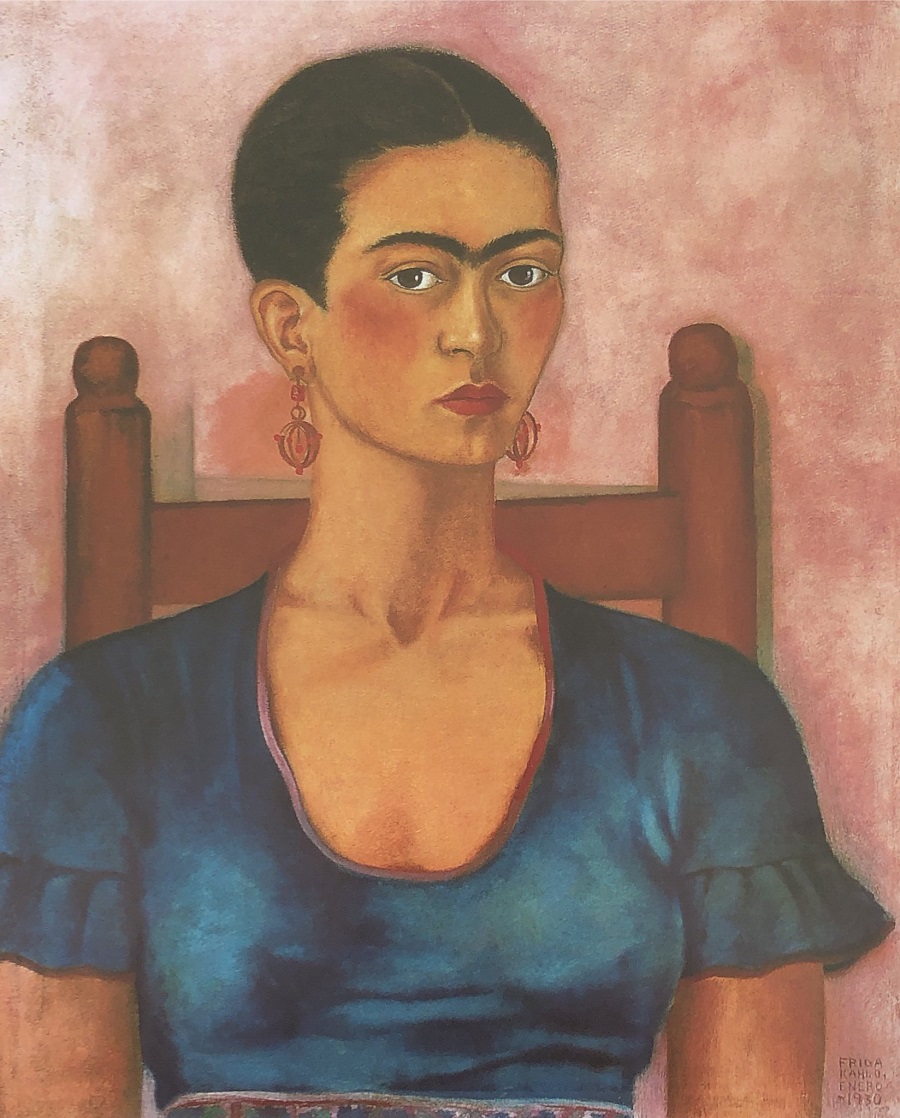

“Self-portrait” (1930). From westwing.es

Kahlo's enforced prostration led her to examine her own person, her body and her identity. A mirrored panel above the bed allowed her to embark on the famous series of self-portraits she painted throughout her life. At first, they were austere portraits of a woman with piercing eyes but over time, they would also come to reflect raw emotion, suffering, passion and desire. And although these works would make her an "object of desire" for the Surrealist movement led by André Breton, she never saw herself as a Surrealist painter: in her own words, "Surrealism doesn't correlate with my art. I don't paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality, my own life."

“The Two Fridas” (1939). From inbal.gob.mx

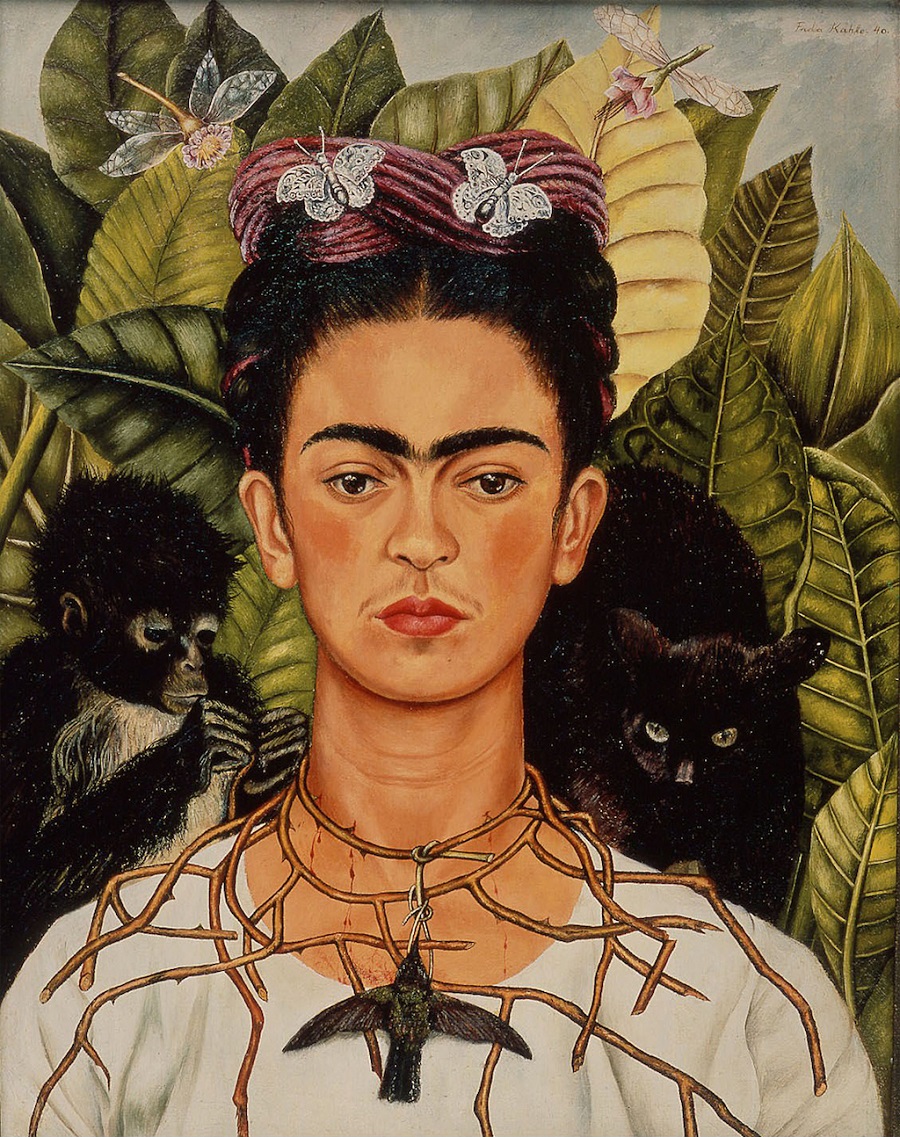

Throughout her life, the exploration of self-identity was a constant in Kahlo's work. In addition to the self-portraits that constituted the most common subject matter of her artistic output, she also reflected on her family ancestry, her friends, romantic partners and close relatives. All of them blended the powerful, primary colors so characteristic of Mexico's plastic and aesthetic cultures, their emotions expressed through visual metaphors: thorn necklaces, animals, blood, tears, corsets ... Her first self-portrait was dedicated to her then boyfriend, Gómez Arias, who distanced himself from her after the accident. Although Kahlo suffered deeply from the breakup (while the young lawyer downplayed their relationship), she would keep in touch with him for the rest of her life.

Diego Rivera. Love, loathing and despair

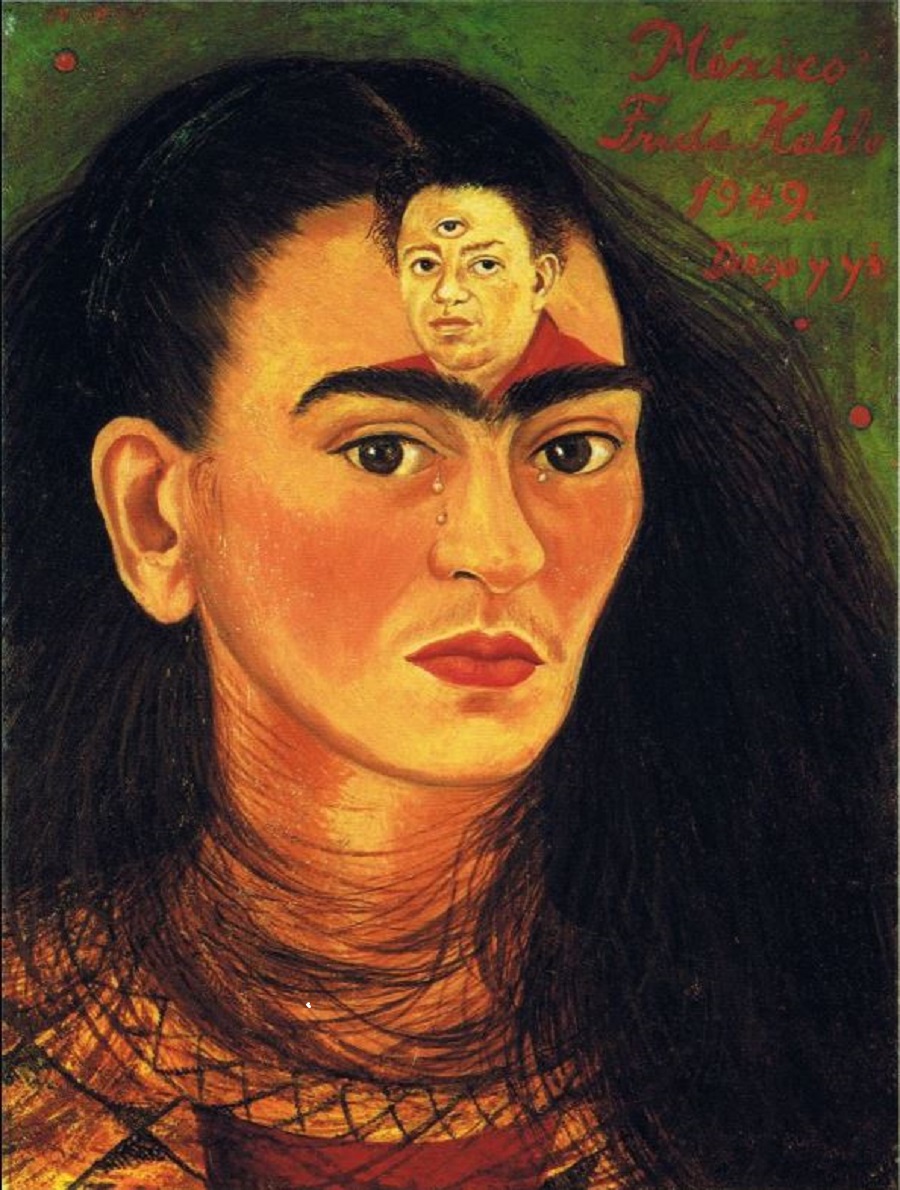

“Diego and I” (1949). From i.pinimig.comm

The accident that destroyed Kahlo's skeletal structure was never an obstacle to her social and cultural activities. From adolescence on, she was no stranger to Mexico City's artistic and political circles. Through the photographer Tina Modotti, she was introduced to the muralist and painter Diego Rivera, who would become the love of her life in a relationship marked by passion, disillusion, jealousy and infidelities. Kahlo painted him on several occasions and described her feelings for him in her diary with phrases such as "I feel that since our very origins, we've been together, that we're of the same matter, on the same wavelength, that we carry within us the same sensibilities" making clear the intensity of her love which was both powerful and destructive.

“Self-portrait with thorn necklace” (1940). From matadornetwork.com

In 1929 and at the age of 22, Frida Kahlo married Diego Rivera, who was then 43. It was "the marriage between an elephant and a dove," in her words. During the ensuing years, they lived together in La Casa Azul (The Blue House), spending long periods in the United States. In this house, and later in the current Studio House Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, the couple keep up an intense cultural and social life characterized by their political commitment to left-wing ideals. In fact, between 1937 and 1939, they would offer asylum to Leon Trotski and his wife who had been persecuted by Stalin. Frida and Diego's relationship underwent countless ups and downs due to the muralist's infidelities, to which Kahlo chose to respond with her own. They divorced in 1939 only to remarry in 1940, this time with a commitment to an 'open' relationship.

The final years. A decade of activity, passion and pain

“Hopeless” (1945). From es.blastingnews.com

The 1940's were a decade of intense artistic activity for Kahlo but although she was long thought to have been overshadowed in life by Diego Rivera's powerful presence and did not at that time achieve the fame afforded to her husband, her work was indeed recognized by artists such as Breton, Picasso and Kandinsky, among others. In 1938, the Julien Levy Gallery in New York organized the first solo exhibition of her work and she began participating in collective exhibitions. Her work was exhibited in Mexico, Paris, New York, Boston and other American cities. In 1942, she joined the Seminary of Mexican Culture as a founding member and in 1943, she joined the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving "La Esmeralda" as a teacher. In 1953, the year before her death, the Lola Alvarez Bravo Gallery organized a solo exhibition of her work in Mexico City which would turn out to be the only one held in the country during her lifetime.

“Frida's Eyes” (1948). From bodegonconteclado.wordpress.com

Kahlo's physical and medical problems left her incapacitated in bed for long periods but she persevered with her painting and created magnificent portraits full of symbolism, depth and personality. This was the case with "Frida's Eyes" (1948), a work that reflects two of the constants in her painting: suffering and a passion for Mexican traditions. Pain and the proximity of death, which Kahlo felt was fast approching, are recurring themes on her canvases. In 1950, her health deteriorated due to spinal surgery that caused her significant problems. In 1954, Kahlo attempted suicide twice, unable to endure the pain any longer. That same year, Kahlo died at the age of 47 and her coffin, draped with the Communist flag, was placed in the capital's Palace of Fine Arts, where the most prominent Mexican artists and intellectuals of the day came to pay their respects.

Exhibitions

Frida Kahlo (2010)

In 2010, Vienna's Kunstforum organized one of the largest ever retrospectives of Kahlo’s work. In total, the exhibition included some 150 works, among them many of her most famous self-portraits.

Frida Kahlo. “Paintings and drawings from the Mexican Collection” (2016)

Kahlo's connection with the Soviet Union dates back to her youth. She always expressed her commitment to communism, social engagement and the most vulnerable members of society. In 2016, present-day Russia organized an exhibition in her honour at the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg: it was the first time her work had ever been shown in the country. The exhibition included some 34 pieces including paintings, drawings and photographs.

Frida Kahlo: "I paint myself” (2017)

"I paint myself because that's what I know best." These are the words with which Kahlo justified her obsession with self-portraiture. The exhibition held at the Dolores Olmedo Museum in Mexico City was a compilation of 26 works from the museum's own collection returning home although for a limited time only, as they are constantly out on loan to exhibitions around the world.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances can be deceiving (2019)

Kahlo's unique and inimitable style was without doubt an indissoluble part of her own identity and what made her an omnipresent plastic and aesthetic icon of the 21st century. The artist defined herself in her paintings and in her persona through illness, political engagement and cultural kinship. This Brooklin Museum exhibition was the largest in the United States for ten years and, in addition to paintings, included personal items, clothing and intimate treasured possessions only discovered in 2004.

Books

“The Diary of Frida Kahlo: an intimate self-portrait ”. (La Vaca Independiente)

Frida Kahlo’s life and personality, as well as her work, cannot be understood in all their magnitude without reading her diary. Written during the last ten years of her life and locked away for nearly 50 years, it is a raw testament to the painter's private feelings. Illustrated with fantastical watercolors and shot through with her unbridled and destructive passion for Diego Rivera, the journal has a prologue by the author Carlos Fuentes and includes an essay by Sarah M. Lowe. 170 pages of art, emotion and intimacy.

“Frida Kahlo: Beneath The Mirror”. Gerry Souter (Parkstone Press)

Frida Kahlo used herself as the exclusive model for dozens of self-portraits. It is precisely these works that conceal and distill the essence of her life, her history and her feelings. They are, without a doubt, the best autobiographical testimony we have of the artist. Gerry Souter's biography uses these works and other paintings to articulate her story. The writer later wrote a second volume dedicated to Kahlo's husband and muralist and painter Diego Rivera.

“Frida Kahlo: Fantasy of a Wounded Body”. Araceli Rico (Plaza y Valdés)

The author Araceli Rico was one of the first to recognise the enormous importance of Frida Kahlo's work in the sphere of world art. Page by page and word by word, the internal tension that Kahlo always experienced is revealed, as is the symbiosis she experienced between art and life, body and painting. This is an essential book to get to know both the person and the painter, both trapped in the same body, both loved and tortured.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Frida Kahlo: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -