Tamara de Lempicka never gave up her independence and freedom. She maintained both thanks to her inate talent for painting, which gave her fame and fortune during her time. Nowadays she is considered the Queen of Art Déco, and her paintings are included in the best public and private colections of the world.

An artist in constant self-reinvention

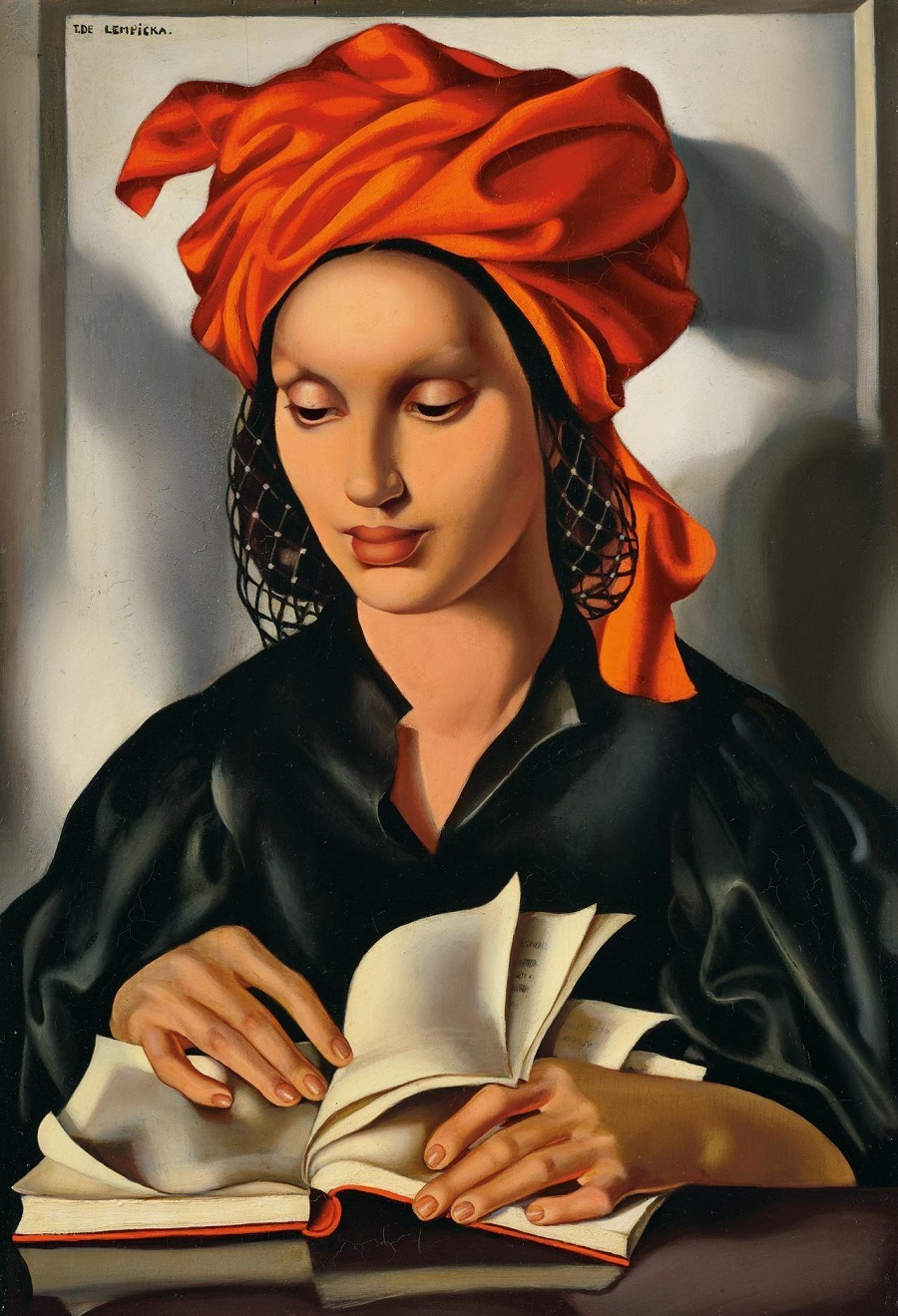

Tamara de Lempicka painting “Suzanne Bathing” (1938)

Tamara de Lempicka was not always acclaimed as an artist. At various times in her life, she enjoyed huge recognition and was, in fact, one of the few women who managed to earn a living as an artist. But in her later years, during the heyday of American abstract expressionism when anything remotely resembling the figurative was shunned, her work lost critical acclaim and even interest. In recent decades, however, de Lempicka's work has been rediscovered and reappraised, and although she figures today as one of the most sought-after artists of the 20th century, her life and character are still somewhat of a mystery - her inherent mythomania having driven her to invent her own narrative in which reality coexisted with pure fabrication.

What we do know to be true, however, is the power, solidity and innovation her paintings brought to the art scene in the first half of the 20th century. In particular, her portraits and female nudes have become the iconographic paradigm of the Art Deco movement, being very much in demand by celebrities and collectors alike. De Lempicka was very clear about who she was and, above all else, who she aspired to be. "I was the first woman to paint pictures that were neat, precise and finished and that was the secret to their success. Out of a hundred paintings, it was always possible to recognise mine. And the galleries tended to centre me in their best rooms because my art was attractive to the public." - something that remains true today with de Lempicka's work attracting thousands of visitors to museums and exhibitions for their remarkable modernity, harmony and timeless qualities.

Childhood in Russia and first contact with classicism

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact date of de Lempicka's birth. Her penchant for reinventing her own story meant she blurred biographical data to such an extent that even the experts are confused. However, many biographers are agreed that she was born in Warsaw in 1898 while, according to the artist, she was born in Moscow in 1907. What is unequivocal, though, is that her father, a well-to-do Russian lawyer, moved the family to St. Petersburg when she was still a child.

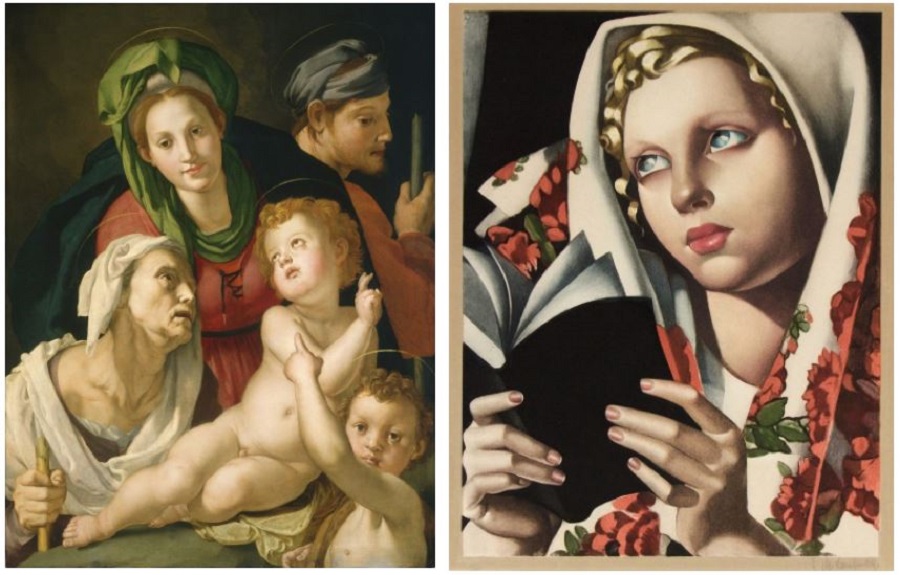

The Holy Family (1527-1528), Agnolo Bronzino. The Polish Girl (1933),Tamara de Lempicka

During her childhood, de Lempicka's first contact with art had a deep impact on the budding painter's impressionable young personality. Her aristocratic grandmother took her on a trip around Italy in 1911 when she was just 13 and which she later described as: "Suddenly, I came across works painted in the 15th century by Italian artists. Why did I like them so much? Because they were so clear, so sharp ..." The clean lines and saturated surfaces characteristic of Italian Mannerists were to exert a powerful influence on her art, an influence that would last for the rest of her life.

Escape to Paris and years of artistic training

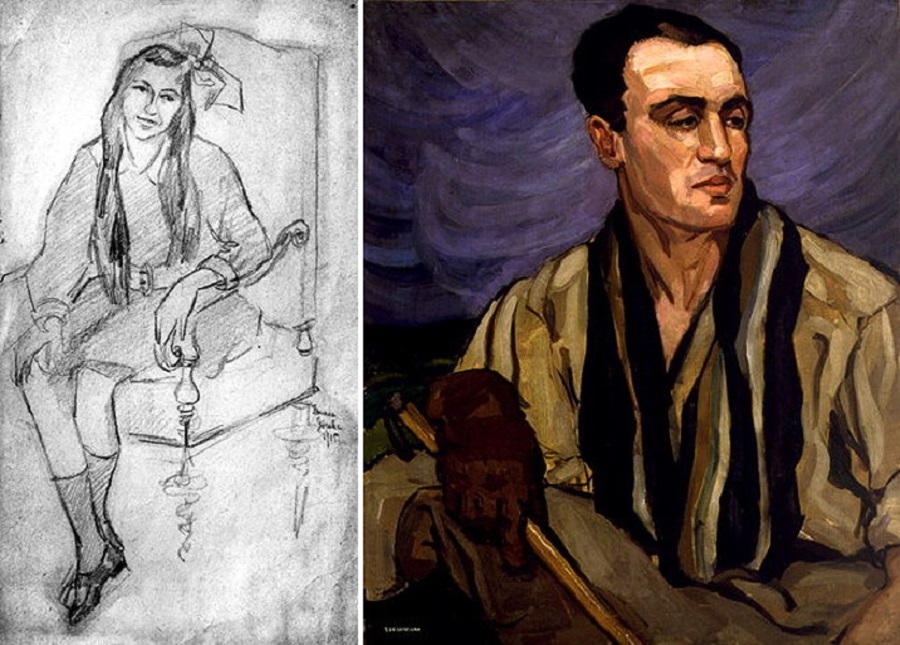

“Portrait of Irena Kleinman” (1915) and “Portrait of a Polo Player” (1922)

Despite her obvious passion for art, the future artist did not take up painting during her teenage years. As was usual at the time and in the wealthy social class to which she belonged, at just 18 she married the Russian lawyer Tadeusz Lempicki and had a daughter, Kizette. It is a year of luxury and glamour and the couple are the toast of society salons and dinner parties just before the eruption of the Russian Revolution in 1917. And then things change radically: Lempicki is imprisoned and only freed thanks to the perseverance of his young wife, who leaps into action and appeals time and again, office by office, for his release. The Lempicki family flees to Denmark and then to Paris, where they are forced to confront a new adversary in the form of financial hardship and a lack of the luxuries to which they had been accustomed. Her sister Adrienne, who lived in Paris at the time and was fully integrated into the modernity of the city (which advocated for the liberation of women and their equality with men in terms of rights and obligations), gives her the best advice of her life: "get a career and you won't have to depend on your husband."

In later life, de Lempicka would define herself on various occasions as a self-taught artist. During her early adulthood, however, she studied at several Parisian institutions, from the Académie de la Grande Chaumiére (where she trained under the Symbolist painter Maurice Denis) to the Académie Ranson, founded by the Fauvist Paul Ranson. She also spent whole days at a time in the Louvre, soaking up the work of the masters. But, without a doubt, her greatest mentor was the fauvist André Llhote, from whom she absorbed and internalized the ability to capture solidity and volume in forms, while applying some of the fundamentals of Cubism (especially the fracturing of perspectives and the distortion of shape).

On society's margins: the 1920s

“The Kiss” (1922)

"I live life on the margins of society, and the rules of normal society don't apply to those who live on the fringe." de Lempicka once said. She always considered herself an exceptional, privileged person and took pains to create and maintain a close relationship with the highest aristocratic circles and uppermost echelons of the avant-garde of her time. It was in 1922 that she added the "de" (of) to her surname and began modifying and creating her new biography. De Lempicka was a regular at literary salons where cocaine, hashish and alcohol flowed freely and, as Jean Cocteau once commented, she adored "art and high society in equal measure". Her bisexuality, widely tolerated by the circles she moved in, is faithfully reflected in many of her works. The artist's paintings leave no doubt as to their celebration of the female body in all its potency and solidity, and in their depictions of love and sexual attraction between women.

“La Belle Rafaela” (1927)

Works such as "Group of Four Nudes" (1925) or "La belle Rafaela" (1927) show tightly-cropped areas totally occupied by close-ups of naked female bodies in openly sexual positions and with the flat, geometric and sharply outlined style that have made de Lempicka's work the paradigm of Art Deco. The influence of 19th century masters is evident in these works and clearly linked to the paintings of Ingres and Manet. Like the latter's "Olympia", Rafaela was a prostitute from Marseille (and also one of her lovers) but, unlike the woman portrayed by Manet, de Lempicka's Rafaela is virile, voluptuous and totally indifferent to 'the male gaze' and male judgment. Also around this time, she paint the portraits of many aristocratic figures, thanks to the sale of which she was able to maintain her high standard of living.

Success, separation and war: getaway to the U.S.A.

“Self-portrait in a green Bugatti” (1929)

In the 1920s, de Lempicka became the darling of the aristocratic, high society set but it was in the late 1920s and early 1930s that her success reached its height. In 1929, she painted one of her most famous works, "Self-Portrait in a Green Bugatti", that would become the most famous and recognizable icon of Art Deco painting. On the canvas, the subject looks defiantly at the camera and paints herself in the driving seat usually occupied by men. It was commissioned for the front cover of the German fashion magazine Die Dame (The Lady) and is a compendium of the artist's unique and personal style: fully covered surface, geometric and outlined areas, metallic reflections that make it almost impossible to distinguish between metal and fabrics, and a blatant challenge to 'the male gaze'. This period of success is followed by a dark time for de Lempicka: that same year she divorced her husband and, in 1933, her commissions began to dry up due to the economic crisis occasioned by the Great Depression.

"Wisdom" (1940-41)

In 1939 and on the brink of WWII, de Lempicka marries Baron Raoul Kuffner and the couple move to the United States. She chooses a destination to match her aspirations and lifestyle: Hollywood. However, the reception afforded her in the United States is not what she expected - in her new home she is considered a "hobby" artist who painted for fun. In 1949, they move again, this time settling in New York where she continues to paint but in a style more reminiscent of the Old Masters than her work from the 1930s. She also dabbles in interior design, creating makeover projects for the homes of high society clients.

Final years in Mexico

In 1962, Lola's Gallery in New York held a solo exhibition of de Lempicka's work. The critical reception was lukewarm but she persevered with her painting, regardless. That same year, her husband died suddenly and she moved to Houston to be closer to her daughter who lived there. In her final years, de Lempicka decided to move to Mexico, a country that became her final home, having always been close to her heart.

In 1972, the Luxembourg Museum in Paris organized an exhibition that rekindled public interest in her work and brought about the artist's reconciliation with critics. In 1980, de Lempicka died and, following her express wishes, she was cremated and her ashes scattered around the foothills of Popocatepetl volcano.

Exhibitions

Tamara de Lempicka (2015)

In 2015, the Italian city of Turin exhibited the well-known "Girl in Green", on loan from the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which triggered a large retrospective of de Lempicka's work that filled out galleries in the Polo Reale museums and the Chiablese Palace.

The many faces of Tamara de Lempicka (2019)

“The many faces of Tamara de Lempicka” was the name the Kosciusko Foundation of New York chose for its retrospective of the artist. The exhibition afforded the public an opportunity to admire a wide selection of paintings and drawings documenting the artist's life during the nearly six years she spent in the artistic capital of America.

Tamara de Lempicka: Queen of Art Deco (2015)

In 2019, The Gaviria Palace organized a grand exhibition on the "Queen of Art Deco", with a view to reigniting the Madrid public's interest in de Lempicka's painting. The retrospective brought together over 200 works in total, loaned by nearly 40 public and private collections against a backdrop of magnificent Art Deco design objects from the period.

Books

“De Lempicka”. Giles Néret (Taschen)

The German publisher Taschen does an excellent job of compiling de Lempicka's oeuvre in this essential guide. In it, historian, journalist and art conservator Gilles Néret frames the painter's work within the collective memory of the 1920s and the history in general of women artists.

“Passion by Design. The art and times of Tamara de Lempicka (Revised)”. Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall (Abbeville Press)

Who better than her own daughter, Kizette, to do a fascinating analysis of Tamara de Lempicka, the person? To this day, the book remains the definitive compilation of her life and work. The new edition is illustrated with excellent reproductions of her most famous works and includes never-before-seen documentation, including private photographs from family albums. The introduction is written by Marisa de Lempicka, great-granddaughter of the painter.

“Tamara de Lempicka”. Virginie Greiner and Daphné Collignon (Planeta Cómic)

Nothing like art to illustrate (or recreate) part of de Lempicka's life. In this case, it is that of V. Greiner and D. Collignon, creators of a graphic novel full of beauty and passion. A book that reflects de Lempicka's talent, freedom and powerful personality in fictional form.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Tamara de Lempicka: Biography, works and exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -