It must have been a dazzling sight to behold when the waters of the Nile flooded the lowlands of Ancient Egypt. The ground disappearing, the ditches filling in, villages emerging as if tiny islands and the swelling of the river setting the rhythm of time. There are some 1,000 kilometres between Aswan and the Mediterranean and covering three-quarters of this distance, Upper Egypt is a furrow hollowed into the desert.

Lintel of the temple of King Amenemhat III (detail), Egypt, 12th Dynasty, 1855-1908 BC, British Museum

It must have been a dazzling sight to behold when the waters of the Nile flooded the lowlands of Ancient Egypt. The ground disappearing, the ditches filling in, villages emerging as if tiny islands and the swelling of the river setting the rhythm of time. There are some 1,000 kilometres between Aswan and the Mediterranean and covering three-quarters of this distance, Upper Egypt is a furrow hollowed into the desert. The rest is made up of the delta, so called because the Greeks recognized in its triangular shape the fourth letter of their alphabet.

Around 5,200 years ago, some of the peoples living on the banks of the Nile among the papyrus plants and palm trees must have felt the need to reflect everything around them in writing and chiselled out the first ever hieroglyphs in history, in some or other pieces of stone. The oldest we know of date from 3,250 BC and together with cuneiform script are the earliest forms of human writing. How many thousands of years must human beings have been interacting without feeling the need to write anything down until then?

Lintel of the temple of King Amenemhat III, Egypt, 12th Dynasty, 1855-1908 BC, British Museum

London, in early 2023, finds itself embroiled in the furore surrounding the recent appointment of yet another Prime Minister and the upcoming coronation of Charles III at Westminster Abbey. However, one would be hard pressed to hear a pin drop in any of the galleries of the British Museum "Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt", a display featuring 240 objects from national and international collections in celebratation of the two hundred year anniversary of the decipherment of the Rosetta stone.

Exhibition room at the British Museum during "Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt"

The exhibition, dimly-lit and its black walls painted over with silver hieroglyphics, accentuates the sensation of being inside a pyramid. At its conclusion, in the final room, scenes of the banks of the Nile are projected in the round - its feluccas and palm trees, its temples and obelisks, its pyramids and birds in flight and behind them, the whole sea of the desert.

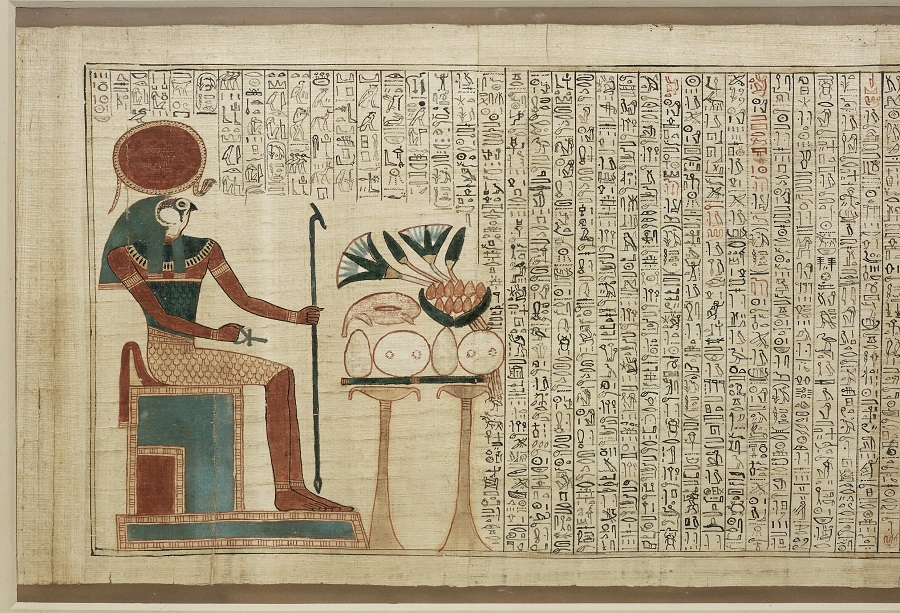

Fragment from the Book Of The Dead of Nedjmet, Egypt, 11th Dynasty, c. 1069 BC, British Museum, London

Sarcophagus of Hapmen, Cairo, XXVI Dynasty, c. 600 BC, British Museum, London

The display cases of the exhibition contain fascinating objects such as Champollion’s and Thomas Young’s own personal notes, four canopic vases preserving the organs of the deceased, the bandage of the Mummy of Aberuait and the 3,000-year-old Book of the Dead of Queen Nedjmet. Papyrus grew abundantly on the fertile, marshy banks of the Nile - a plant, whose name derives from the Greek word meaning "royal", raises its umbrella head on a stem that can reach up to six metres in height. Their stalks were used for shipbuilding, their fibres served to make ropes, mats, sails, baskets and sandals while its central pith created the papyrus on which to write.

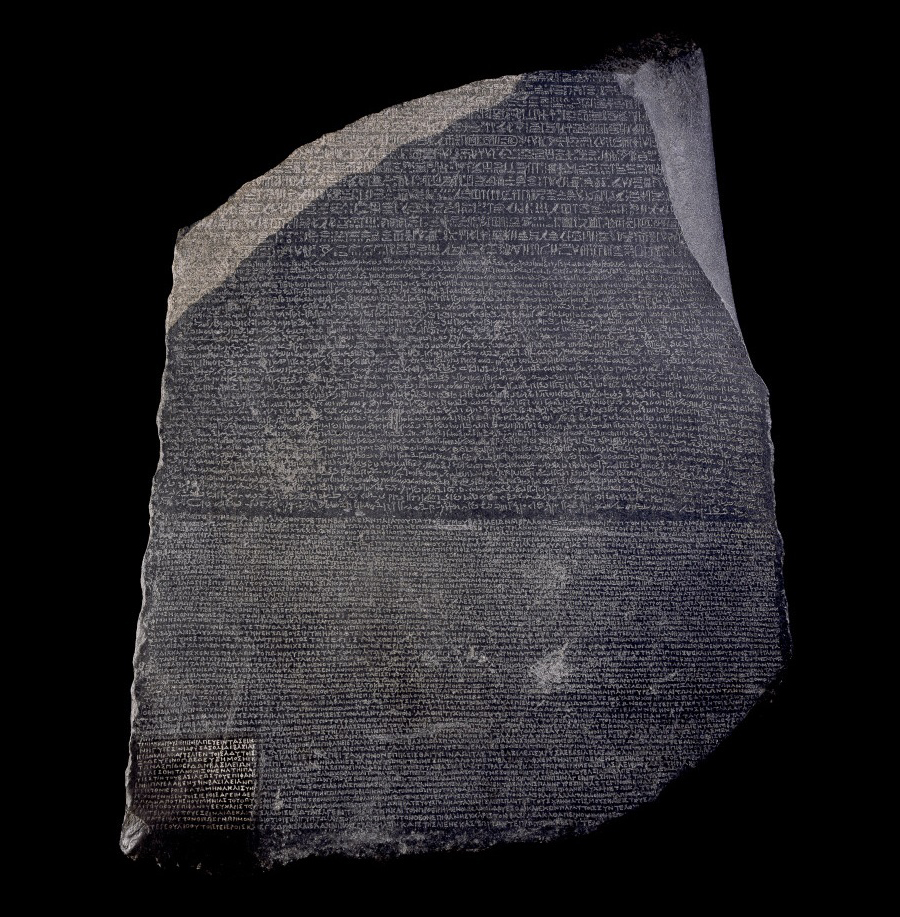

Mummy of Bakentenhor, 12th Dynasty, 945-715 BC, Great North Museum

Nevertheless, the centrepiece of the exhibition is the Rosetta Stone, spot-lit as if by a magic beam, as if it were kryptonite. This fragment of an ancient stele is synonymous with the hieroglyphs that covered statues, monuments and papyri in Ancient Egypt. Its pictorial-style script was closely linked to Egyptian culture but although it was never used elsewhere, it was imitated throughout the kingdoms of ancient Sudan and appears to have inspired the Proto-Sinaitic script, in turn a possible distant ancestor of the modern alphabet.

Rosetta Stone, 196 BC, Ptolemaic Dynasty, British Museum, London

The first pages of Jean-François Champollion’s book, “Egyptian Pantheon”, open with a description of Amun - a god in human form usually seated on a throne. His skin is blue and his beard is styled as the black appendage characteristic of male divinities. When this same appendage appears on coffins, it indicates the mummy of a male. Held in his left hand is a sceptre crowned with a bird's head and it is the sceptre common to all the male divinities of the Egyptian pantheon. In his right hand, he carries a cross, surmounted by an oval or handle-shaped loop - the symbol of divine life. He wears a tall double-plumed royal headdress. A long blue ribbon cascades down his back. It is an aesthetic so powerful it begs the question - if the 19th century was one of revivals, namely, the use of visual styles that consciously echo an earlier architectural era (this being the case of Pompeii and Pompeian styles, Gothic and Gothic Revival and Neoclassicism), what then is the reason why a taste as refined as that of Pharaonic Egypt was not also taken as inspiration for the decoration of future palaces, clothing, furniture or tableware?

Statue of an anonymous scribe, Egypt, 5th Dynasty, 2494-2345 BC, Louvre Museum

The story of the Rosetta Stone has an inexplicable force. In December 1797, Tipu Sultan of Mysore in India asked Napoleon for help in quelling the growing threat of British power in India. It was then that, in the margins of a book about the Great Turkish War, Napoleon wrote: "Through Egypt, we will invade India." Emboldened by victories in Italy but frustrated by his attempts to invade England, Napoleon landed in Alexandria on July 1, 1798 with an army of 40,000 men. He was accompanied by the Commission des Sciences et des Arts (Commission of the Sciences and Arts) that brought together the most brilliant French minds and that, in the spirit of the prevailing Enlightenment, was to investigate and map both ancient and modern Egypt.

In mid-July of 1799 and faced with an imminent attack by Ottoman naval forces wishing to avenge Napoleon's campaign in Syria, the French reinforced their coastal defences. In Rashid (Rosetta), a port city on the western bank of the Nile delta, the demolition of Fort St. Julien was ordered and a block of granodiorite stone appeared among the foundations, a fragment from an ancient Egyptian stele with a decree published in Memphis in the year 196 BC under the name of Pharaoh Ptolemy V. The decree appeared in three different scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphs at the top, Greek at the bottom and between the two an unknown inscription initially believed to be Syriac.

Its pivotal role in the decipherment of hieroglyphs was immediately recognized. It was dug out of the dust, cleaned, and the Greek section was translated. Afterwards, it was transported by boat up the Nile to the Cairo Institute where its discovery was announced on August 19, 1799. There, the first and most crucial task was to make exact duplicate copies of the texts. Two young Orientalists recognized the central inscription as Demotic, a cursive script of the Egyptian language that they had seen before on papyri and mummy bandages.

Copying by hand would have meant, in addition to the risk of human error, months of work. It was decided to clean the stone and to leave the water in the crevices, its surface was covered with ink and traced onto sheets of damp paper. Thus, on January 24, 1800, a reverse copy was created in black on white that could be read with a mirror or via a light source. In Paris 22, years later, Jean-François Champollion presented his discoveries on hieroglyphs to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Two weeks earlier and after exhausting and exhaustive research that had seriously affected his health, Champollion had succeeded in deciphering the names of Cleopatra, Ramses and Thutmose III and, therefore, the writing of the ancient Egyptians.

Medal commemorating Thomas Young, mid 20th century, British Museum, London

Over time, the understanding of hieroglyphs was lost as the culture of Ancient Egypt was swept away by waves of conquests and occupations. The Arab invasion of the 7th century brought Islam and with it both the Arabic language and a succession of rulers culminating in the rule of the Mamluks.

Today, the Rosetta Stone is the British Museum’s most visited piece, with the bicentenaries of its decipherment along with that of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb again stirring up one of the most contentious debates of recent times, namely, renewed calls for the restitution of artefacts and antiquities to their countries of origin. The disputes have resulted in some agreements being reached but each case is different and, for Western museums, some emblematic pieces are considered untouchable and will always be the Cultural Heritage of all humankind.

The reflections of Egyptologist Silvio Curto illustrate why that is: "What was established during the Pharaonic era was the concept of the supreme dignity of the human being and that must be returned to and perfected throughout history, from Socrates to Kant."

Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt

British Museum, London

Curator: Ilona Regulski

13 October 2022 - 19 February 2023

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Hieroglyphs : Shining A Light On Ancient Egypt - - Alejandra de Argos -