Trying to review Romanian-born artist Anka Moldovan’s latest exhibition "that which bursts" is, I have to admit, an excersize in arrogance, akin to claiming one can describe the joy felt by a sparrow in flight or the beauty of Handel's "Son nata a lagrimar". It is unwise to even attempt to reduce down to a few words the complexity of her worlds which, while still our world, feature exotic singularities like the event horizon of a black hole.

"Slit-man. Retina" (detail) (2023). Oil on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Trying to review Romanian-born artist Anka Moldovan’s latest exhibition "that which bursts" is, I have to admit, an exercise in arrogance, akin to claiming one can describe the joy felt by a sparrow in flight or the beauty of Handel's "Son nata a lagrimar". It is unwise to even attempt to reduce down to a few words the complexity of her worlds which, while still our world, feature exotic singularities like the event horizon of a black hole.

The beings and ambiences that emerge, pertinatious, from her paintings seem to live on that mysterious fine line between the visible and the invisible, between being and disappearing. Although it would be easy to divide the collection into four categories, there is still a common denominator that forms part of Anka Moldovan's identity as a creator: namely, her efforts to make the air perceptible, the constant human presence, somewhere between the corporeal and the abstract (despite which it is still possible to recognize oneself in some or other of her pedestrians walking with the determination of those who know and own their responsibility) and an undeniable capacity for synaesthesia.

Painting is, in principle, a visual art but, in this case, there are other senses involved. It is impossible not to feel the urge to touch, as if we were blind and reading Braille, the roughness of the reliefs that are an essential part of her work. Their meaning is as suggestive and mysterious as the "Voynich Manuscript" that, 600 years after its writing, remains indecipherable. Moldovan’s paintings smell of the rain and the sea because the beings in them seem always to be living in a thick fog that they wade through fearlessly in order to find us although, along the way, they run the risk of suffering a “Sudden Departure”, a euphemistic linguistic construct used to refer to the disappearance of 140 million people in the series "The Leftovers".

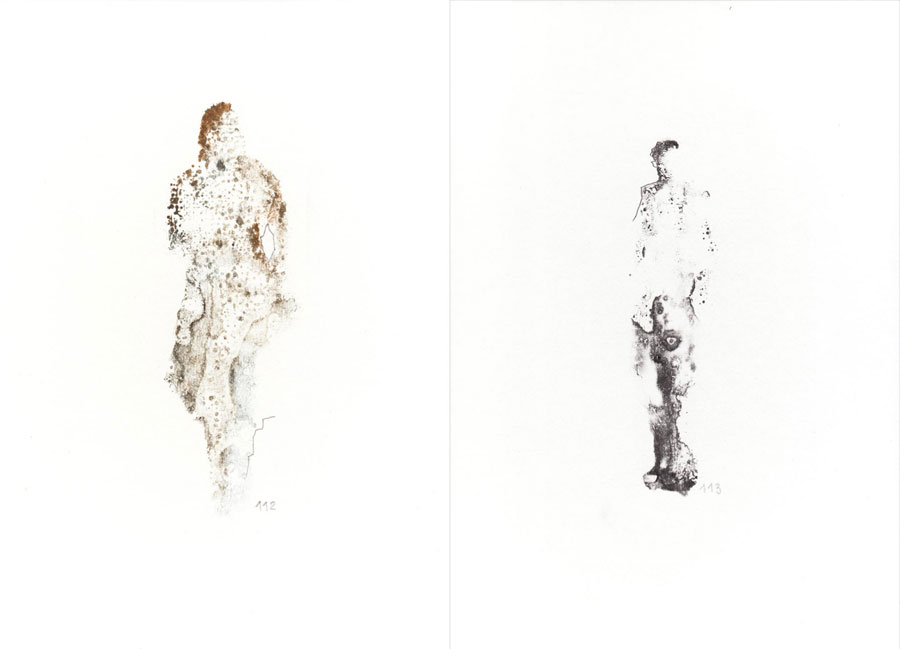

This happens in real terms in Moldovan’s work and comprises the "Reflections" collection - individuals who come to life in her paintings and, in the laborious construction of the fog, with its layer upon layer of oil painted and removed time and time again in search of a veladura glaze, it sometimes happens that one character is transformed, another vanishes into thin air, another fades away and, through a process of transference, is reborn on paper. The price of the pilgrims’ odyssey is to live alone, behind numbered windows and to be the only, or unique rather, creatures who are distanced from the firm, natural support of wood and exist on the human construct of paper. Odd observers these, echoes who from afar observe the paintings from which they come, each one a foreigner who discovers that the best way to accept what they have become is to remember what they once were, as Theodor Kallifatides wrote.

"Reflection 112" and "Reflection 113" (2023). Oil on paper. Courtesy of the artist

Moldovan's work can also be heard because it is narrative, it tells a story, incomplete, fragmented, like the name itself of this exhibition, "that which bursts", barely half a sentence, a subordinate clause lost in a world, our world, full of noise and fury, that shouts without listening and speaks without saying a thing. The art critic Carlos Delgado Mayordomo defines with poetic and meticulous precision: "Pain and love, despair and joy, absence and presence, are – without being exhaustive – some of the recurring themes in her paintings, where the desire to liberate and elevate what is properly human, to transcend it, is always visible."

What we see are troubled beings, carrying the burden of great responsibility, exhausted but not defeated, in pain, determined and ethical. Every paradise is a paradise lost and the visions that the creator portrays remind us that life rhymes with strife and not by chance but by causality. This is nowhere more evident than in the “Slit-men” suite - a transubstantiation of a poem by Nichita Stănescu that describes someone who “comes from beyond / and even beyond that beyond.”

Anka Moldovan, work in progress

The best way to describe them is the photograph above where Moldovan observes her "Slit-man. Presence" with the fascination and curiosity of an entomologist witnessing the arrival of the first insects on a corpse and, given the comforting gesture with which she touches her hair, it would seem that he is a stranger even to her. The four "Slit-men" are subtitled "Presence, Retina, Belly, Breath" and are entities somewhere on the spectrum between the savage and the human. They have arrived, although not through some fancy wormhole but by headbutting their way in. Seeing them gives new meaning to the scene in “Bladerunner” where the replicant Batty's face smashes through a tiled wall in pursuit of Deckard. In these four paintings, of the same height as the artist herself, there is hunger, pain and an intimidating power. They watch us and they see us.

If “Reflections” and “Slit-men” concern being rootless or uprooted, then the paintings from the “Earth” series are literally rooted, with actual roots.

"Earth" (2023). Oil on wood with root. Courtesy of the artist

They are women's heads with eye-catching buns and ornate up-dos, details that form part of the author's memory and memories. Another place, another time, other women and their ancestors, captured in a trivial detail that is testament to their greatness and generosity because their delicate and laborious braiding is seen by everyone else except they themselves. A root emerges from their hair because these women, in 1980s Romania, had their feet firmly on the ground and carried out their duty to care, feed, educate, provide love and security, sow responsibility and empathy and, ultimately, build true human beings.

Above left: "Birthing the world" (2021). Oil on wood. Above right: "Man, joy" (2023). Oil on panel (2023). Courtesy of the artist

With the root of a raspberry bush sprouting from her plaited hair, the natural and the artificial, nature and art share the same space. “It is not a simple stylistic artifice, but a bold reflection on the inevitably symbolic foundation of the visual arts: the roots, without the need to lose their own physiognomy, are read as a coherent part of human representation” according to Carlos Delgado Mayordomo.

And then finally, we come to the walkers, beings similar to us who move through spaces that we recognize (such as Madrid’s Gran Vía), prosaic passengers, citizens who inhabit the months as others inhabit cities and others metaphors. What makes them a society, while still remaining individuals, is that they are essentially beautiful and noble, physically and morally. Committed and empathetic, always moving forward without avoiding life's challenges. It is their greatness that makes me think that they only seem similar to us although, through the kind and loving eye of their creator, it is possible that we ourselves may become free from our sins.

Tireless and determined, they are surrounded by a mystical atmosphere that could be their soul, because they have one, or the air they exhale, because they breathe. One of these works, "Birthing the world" became the cover of the novel "A woman in the making" by Christian Bobin. This carefully crafted edition published by “La Cama Sol” makes for an illustrated book in a double sense, where the words of the gone-too-soon writer of silence and the paintings of the painter-of-air coexist.

"The flow of air". Oil on panel. Courtesy of the artist

"The mystery that bursts from her paintings - explains Carlos Delgado Mayordomo - is not just the expression of beauty but the celebration of life." Whether solid as concrete or ethereal as shadows, Anka Moldovan's beings whisper stories of resistance and hope. The latter is a necessity whereas the former is an act of love, the necessary defeat of oblivion and indifference - the stubborn will to keep asking questions, even if we sense we will never know the answers.

Translated from the Spanish "Los otros mundos de Anka Moldovan" by Shauna Devlin

- The Other Worldliness of Anka Moldovan - - Alejandra de Argos -