- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

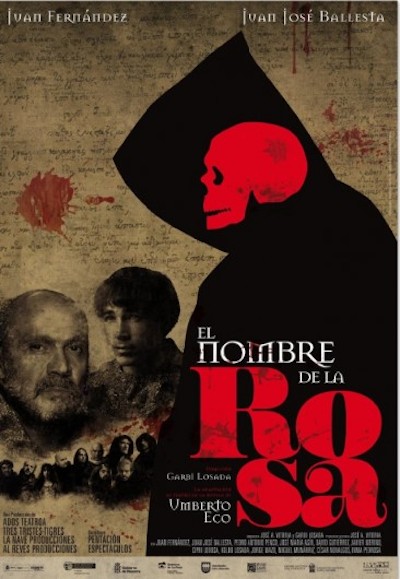

Excellent stage adaptation of " The Name of the Rose ", by Italian writer and philosopher Umberto Eco . This historical novel written by the author at a mature age , was a resounding success , becoming one of the best selling books of the world .

The play set in the late Middle Ages in a Benedictine Abbey , the scene is masterfully led by Garbi Losada , responsible for the direction. Sets, costumes , makeup and lighting did you immerse in the detective story . The cocktail of philosophy , reason, religion and fanaticism is materialized with a brilliant cast of actors.

Juan Fernandez in the role of Friar William of Basckerville Juan José Ballesta in his novice Adso of Melk, are the stars arriving at the Abbey of the most important libraries of Christianity and where they will be given strange murders they will have to solve. Friar William of Basckerville will also have to mediate, at this point of encounter, between the opulence of the Papacy and a Franciscan order with vow of poverty and the Inquisition backdrop.

It was lovely to observe each of the gestures of these artists. It is difficult to single out one among the others because his role was more or less relevant , was brought to the scene with great skill.

I recommend going to see this play and go dressed warm to the New Apollo Theatre , where the scenery was so neat , that made you feel like a guest in the cold abbey. I also suggest before you go ,review over the life of English franciscan scholastic philosopher, William of Ockham ( 1280-1349 ) . The main character, William of Basckerville (wink A. Conan Doyle) and work , are based on this Franciscan who lived in extreme poverty , and left a very important philosophical and theological legacy.

Teatro Nuevo Apolo . Madrid. Until March 30, 2014

- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

I was greeted by warm sunshine when I visited the wonderful gardens of the Zabalaga house, home to the artistic legacy of one of the 20th century’s most important sculptors, Eduardo Chillida (1924-2002). The Museo Chillida-Leku (Gipuzkoa) project was initiated by the artist himself as a place to house a large part of his work. It consists of large and small scale sculptures, drawings, graphical work and his well-known Gravitaciones, also known as reliefs on paper. The archives are located in the old 16th century shed, lovingly restored by Eduardo and his wife Pilar Belzunce: by juxtaposing in this way, an interesting dialogue is created beween his older work and his contemporary work.

“I once dreamed of a utopia: to find myself in a place where my sculptures could rest and where people could stroll among them as if in a forest”.

Eduardo Chillida’s son, Luis, is today head of the Marketing and Communication department. Together we walked through the gardens and the parts of the grounds that were thick with trees, all full of the Basque artist’s sculptures. He told me about the huge effort required to keep the project going — a task which the entire family is devoted to, and which seems to be carried out professionally and responsibly. The grounds measure 13 hectares and are extremely well looked-after; it was lovely to be able to walk at leisure, admiring one beautiful sculpture after another.

Chillida’s unique artistic language, which he has written about in a number of texts, helps us better understand his thought process and his work. Space, time, limits, scale, emptiness, matter and horizon are all ideas which are heavily present in his visual language and which form the basis of his work. Light is another crucial element, one that is especially evident in the alabasters, as well as the idea of limitation. Chillida explores both space and emptiness: he sees both as necessary tools in the making of his sculptures.

Chillida’s philosophy is pure spatial metaphysics, which links him intellectually to Martin Heidegger. The philosopher’s thoughts in “Art and Space” (1968) are so closely aligned to Chillida’s idea of space that he actually asked the artist to illustrate his thoughts for him. According to the philosopher, sculptures create places — without them, places do not exist. I could really sense this philosophy coming alive while we were walking through the grounds.

“I believe that we all come from somewhere. Ideally, we should come from a certain place, we should have our roots somewhere, so that our arms may reach all parts of the world, and so that we may benefit from any culture, no matter where it may come from. Any place can be ideal for those who open their minds; here in my Basque Country I feel at home, like a tree with its roots in the earth beneath it, grounded in one place but with arms open to the world. I am trying to create the work of a man, my own work, and since I come from the Basque Country, my work will have a certain essence to it, a black light, which is uniquely ours.” Eduardo Chillida.

After the visit, I couldn’t help going to see the Ondarreta beach and the Peine del Viento sculpture. Chillida has created a whole new space in this beautiful beach, where one can lose oneself in contemplation of the sky, the sea and the earth among architecture that literally “combs the wind”.

My visit to the area was a great excuse to go on a gastronomic tour in San Sebastián, to please the palate rather than the eyes. This world-class tour is one of the best one can find in this region, where the Michelin stars per resident ratio is the highest in the world.

My food tour started at the Rekondo restaurant and dinner in Zuberoa (1 Michelin star). The following day, lunch at the Asador Etxebarri (1 Michelin star) and dinner at Arzak (3 Michelin stars). We finished off with a trip to Martin Berasategui (3 Michelin stars).

One of my favourite restaurants was the Asador Etxebarri, where Bittor Arginzoniz’s cooking is entirely charcoal-grilled (be it fish, seafood, vegetables or meat). The ingredients were all of the highest quality, full of a delightful charcoal and smoke taste and smell.

My other favourite was Martin Berasategui, where the menu is very light and creative, each dish an exceptional, innovative cooking experience.

In Rekondo I tasted typical home-made Basque food together with a first-rate selection of wines, which I am told is among the best in the world.

Yet another top restaurant is Zuberoa, located in a 15th century Basque country house. The head chef is Hilario Arbelaitz and it boasts a tasting menu that definitely deserves its 1 Michelin star.

To round things up, Arzak was a continuous flow of highly creative sculpture-like dishes. This is avant-garde cuisine which is constantly evolving, very different to what I experienced when I last came here many years ago.

"One must look for the untrodden paths." Eduardo Chillida. Something these chefs have certainly done...

- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

I am excited, increasingly common, to establish dialogue between the art of our time with our artistic past. This exhibition has created a dialogue between the American artist Bill Viola and Baroque masters like Zurbaran, Goya, Ribera and Alonso Cano, which would be the common link emotion.

The museum of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid was the place chosen to present video installations that form the exhibition "Bill Viola in dialogue."

It is understood as a reinterpretation in such an important time in our mood and emotion as feeling. The videos are developed with a slowness that is almost imperceptible, are vivid pictures with a common spirituality works with surrounding facilities.

Revisiting the important collection of pictorial art Academy adds immense value to this exhibition.

The project consists of four video installations, The Quintet of the Silent (2000), Dolorosa (2000), Silent Mountain (2001) and Surrender (2001). They show us a cocktail of intense emotions and extreme suffering, pain and tension spread through the halls and live with the mastery of the classics.

- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

The Helga de Alvear gallery in Madrid recently presented the exhibition Pentagon Principle of the British - Canadian artist Angela Bulloch .

This artist belonging to the group of Young British Artists is known in the field of sculpture and installations.

Her work is based on the sound and visual effects playing with our sense perceptions . This is achieved by current technologies helped with mathematical computer programs .

Pentagon Principle revolves around the pentagon, geometric figure associated with the cosmos in antiquity. The pentagon star was the symbol of the followers of Pythagoras and Plato's Timaeus , the dodecahedron formed by pentagons is associated with the entire Universe.

This exhibition consists of sculptures that play with the figure of the pentagon , either regular or irregular , math created images that are distorted with a virtual computer program and put into reality.

Wall panels , sculptures, light boxes with those released , some with an extensive color range and other monochrome did we entered the microcosm of this artist 's perceptions .

- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

The world premiere of Charles Wuorinen's opera Brokeback Mountain is yet another success for the Teatro Real's former artistic director, Gerard Mortier. His genius, intelligence and sensitivity have brought other gems to Madrid in the past, such as Life and Death of Marina Abramovic (in collaboration with Bob Wilson), The Perfect American (Philip Glass) and Tristan und Isolde (Bill Viola) among others, making his operatic career a point of reference for many around the world. One should also not forget the brilliant transformation of the Madrid Symphony Orchestra (established in 1903) under his supervision (the so-called Mortier era).

I enjoyed the libretto by Annie Proulx, author of the novel on which the film was based. Annie was not very impressed by the film's excess of sentimentality. I felt that this adaptation in opera form was more appropriate for the love story between two cowboys in the rugged mountainous expanse of Wyoming. Mortier understands this love story as "a deep forbidden love, unaccepted by society. It is not so much an American story as it is a universal one" - in essence, the need to be loved, experienced by all human beings.

The score by composer Charles Wuorinen (born in 1938), contemporary and unknown to me until this production, worked beautifully with the progression of the plot and with the singing. It enriched and energised the dramatic love story, making it really take off in the viewer's imagination. The composer's aim, through his music, was to express the overwhelming force of Nature where the story takes place. In this regard, stage director Ivo van Hove accompanies the opera with video projections of the rough , desolate mountains of Wyoming. Only the scenes where the characters' family life is the focal point are more theatrical.

The two leads are played by Tom Randle, a tenor from USA, and Daniel Okulitch, a Canadian bass-baritone, and the music direction is by Titus Engel. This is a must-see event, playing at the Teatro Real until February 11, 2014.

- Details

- Written by Matteo Mottin

|

Autor colaborador: Matteo Mottin |

|

From January 16th Gagosian Gallery Rome hosts a two-person exhibition by Kathryn Andrews (Mobile, Alabama, 1972) and Alex Israel (Los Angeles, 1982). Both artists share a peculiar characteristic: they use temporality and contingency as new parameters for readymades, as a sort of renewal of Duchamp’s undermining of the status of authorship. Furthermore, they’re both based in Los Angeles and they’re interested in the culture of the local film and media industries. The multifaceted nature of Andrews’ work reflects her sensitivity to the decentralized urban sprawl of Los Angeles. Often she combines a meticulously fabricated “framing” element with a second notable object, the juxtaposition of which invites a multitude of implied narrative projections, while simultaneously de-stabilizing traditional assumptions about the formal hierarchies of sculptural pedestal, armature, and object.

|

| Alex Israel, “Abbot Kinney Mural”. Foto: Michael Underwood |

|

| Alex Israel, Museo Civico Diocesano di Santa Maria dei Servi, Città della Pieve. Foto: Ornella Tiberi |

Los Angeles is also a strong presence in Alex Israel’s work: from the set of vertical backdrop panels shaped like the windows and the doorways of the Spanish Revival homes of Hollywood’s Golden Age, painted with a thousand of overtones recalling the colors of LA Valley sunsets, “natural” environment for the rented movie props he exhibits as readymade sculptures, to “As it Lays”, his cult series of video-portraits of such notable locals as Rick Rubin, Marilyn Mason and Christina Ricci, just to name a few, to which he ask such harmless questions as “if you were to create the perfect salad, what would be the key ingredients?”.

The city is also an implicit presence in the name of his sunglasses’ brand, “Freeway Eyewear”.

Matteo Mottin in conversation with Alex Israel.

ATP: I know you’ve been to Cinecittà recently.

Alex Israel: I first went to Cinecittà last year in preparation for my first exhibition in Italy, which was in Umbria, in Città della Pieve, in a beautiful deconsecrated church with a Perugino Fresco, that is now a museum: Santa Maria dei Servi. I went to Cinecittà looking for props to rent, to use as sculptures for the exhibition as part of my ongoing sculptural project: Property. Employing cinema props as readymade sculptures is something that I’ve done in Los Angeles, New York, Berlin and Paris. When I returned to Cinecittà earlier this month, in anticipation of this exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in Rome, it felt like I was coming back to visit some old friends, the incredible props in the “Plastica” department at the studio. My selection process, choosing which props to use, is a lot like casting actors for a film. I walk the aisles at the prop houses, auditioning the objects for the role that they would have to perform in a show: the role of readymade sculpture. I look at the objects and I consider which ones have the most star quality. It’s really hard to explain what exactly I’m looking for–it’s an unmeasurable and ineffable quality–it’s something that you just feel. I spend a lot of time looking at things, taking pictures of the things that resonate for me, and then I begin making a selection. At this point it sort of becomes a “call back” situation, before the final selection is determined. Part of what inspires the selection is how the different objects relate to each other, and how I think they would work as a group or as an ensemble cast, working together in an exhibition. Because this is a two person show, of my own work and Kathryn Andrews’ work, there was definitely a consideration of how any objects that I might choose would relate to her works as well.

I believe that cinema props accrue a kind of magical property, or stardust, over time, through their experiences in film or on television. I feel this quality emanating very strongly from the objects that I’ve discovered here in Italy.

ATP: I read in an article about you that the subject of your research is the vacuity of celebrity culture, so I wanted to ask you…

A.I.: Sorry, that’s not correct. Not at all. I’ve never said that and I think it’s important to point that out here and now. I’m not interested in vacuity or emptiness. I think that celebrity culture is our culture, and I’m really interested in it and inspired by it. Some of my work engages celebrities. A lot of the celebrities I’m interested in are people that have made groundbreaking decisions that have paved the way for other people to follow in their footsteps. This is the fabric of our culture, and it’s neither empty nor vacuous.

A.I.: You invented a new way of intending readymades, giving new meaning to what they can be. How did you come to this? How did it start?

I was in art school and I was having an existential moment, not knowing what to make, or how to produce artwork. At the time I was genuinely convinced that I did not want to make art objects that could exist permanently as artworks and circulate in the art market system. On the other hand, I wanted to create art experiences that could be sculptural or physical for the viewer, much like the experiences of art objects I’ve had in the past–experiences that I’ve truly loved. I came to the conclusion that the best way for me to deal with this paradoxical interest, and to address the entertainment culture that is so interesting to me, and so much a part of life in Los Angeles, was to start thinking about renting cinema props. I started going to prop-houses. In LA we have so many of them and together, spread out across the landscape, the prop houses constitute a kind of library of objects. I just started going to them, taking pictures while learning, from experience, how certain things I’d come across might speak to me. At the same time, I was making sunglasses, and I was making videos for the internet. I insisted that my sunglasses were not precious, they were just a product that could exist in the world, and I knew that my video were also not precious, because they existed online and anyone could download them. I also knew that I didn’t want to alienate the possibility of participating in a dialogue that exists around the art gallery context. The idea of renting props, each able to perform the role of sculpture in a gallery, satisfied everything that I was looking to engage in my work at that time. Everytime I make new works in this way, I reconfirm my belief in the power, magnetism and magic of these inanimate cinematic objects.

ATP: So it kinda rises from an inner necessity.

A.I.: For as long as I can remember I’ve been making art. I studied art in college, and after college I worked in the art world. I experienced the art world from many different points of view: from working with artists, to working at art museums, to working with an auction house and two galleries. I saw the art market balloon into this incredibly powerful force, at times overpowering art itself. When I started graduate school in the fall of 2008, the subprime market crashed, and the art market changed along with it. I had collected a lot of experiences, and a lot of information during that time between college and graduate school, but I was still processing all of it. I didn’t know what to make of it and I guess that’s where the existential mindset came into play.

ATP: Sunglasses always remind me of “La Dolce Vita” and “8 1/2″. The way the characters wear sunglasses in Fellini movies is particular, almost ambiguous, as if they were children pretending to be grown ups, using them to shield their immaturity.

A.I.: Sunglasses are really interesting to me when I stop and think about them. I like how sometimes people wear them to hide, while other times people wear them to be noticed. They have this special quality that changes people: when people put them on, they instantly feel cooler. They’re kind of like a healthy version of smoking a cigarette. For those of us who live in Los Angeles, they are very simply a part of our everyday lives–you put on your underwear and you put on your sunglasses. So on the one hand they’re glamorous, and on the other hand they’re completely banal. I love these dualities, but I also Iove that at the root of it all, sunglasses frame and filter what we see, and they do it so effortlessly.

ATP: A last question: if you were to create the perfect salad, what would be the key ingredients?

A.I.: That’s a good question. Romaine, rucola, spinach, tomatoes, parmigiano cheese, chicken, green beans, corn, pecans, pomegranate seeds and light balsamic vinegar dressing. And avocado.

|

Alex Israel Veduta dell’installazione di autoritratti del 2013 ad Isbrytaren, prodotta a Stoccolma da Carl Kostyal. Foto: Jean-Baptiste Beranger |

|

| Alex Israel, “As It LAys” dalla mostra personale del 2013 presso Le Consortium a Digione. Foto: Zarko Vijatovic |

|

Written by our friends at ATPdiary.com in colaboration with Matteo Mottin |

- Details

- Written by Alejandra de Argos

Carlos Cruz-Diez, born in Caracas in 1923, is one of the great exponents of kinetic art. He moved to Paris on October 12, 1960 with a view to making it his permanent base. He set up a studio on rue Pierre Sémard and gradually went about expanding it to include other spaces on the same street.

Today his workshop is spread out across a number of properties interestingly, one of his studios still has the same façade from when it used to be a butcher’s shop. Cruz-Diez has assigned a specific purpose to each space: a documentation centre (which holds part of the documentation, the rest being found in his Panama studio), a meeting room, and a space dedicated to restoration work which also contains his work archives. His work area, or experimentation studio, is quite fascinating: so full is it with all manner of tools and equipment that it could well be mistaken for a goldsmith’s workshop instead of a painter’s studio. It was precisely this variety that made the visit so informative and engaging.

His family has continually worked together towards the long-term conservation and organization of the work and legacy of an artist who can only be described as one of the great scientists of colour.

Here we can see the artist posing in front of one of his later paintings (one which I particularly liked), displaying surprising charm and energy for a 90-year-old.

I was able to follow the great artist’s extensive exploration in colour and movement through time, appreciating how Cruz-Diez’s artistic experimentation had evolved, from the use of cardboard and wood at the beginning to numerical technology and aluminium in his later work. He has engaged in a lifelong exploration into the use of his materials, always with the aim of finding the best possible method of expressing his ideas. The one constant in his work is the perception of colour, and the feelings that colour generates in the viewer. He wants us to see colour as having a life of its own.

But the materials and the technique are not at the centre of his work — rather, his main interest lies in making the viewer reflect on the art. The physical painting is nothing but an instrument through which Cruz-Diez expresses his ideas to us. The gloss, the brush-strokes, the style: these are not the focal point of his art. Much like an architect, he designs his blueprint for others to reflect on it and make sense of it. A rational, almost conceptual approach.

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez. Fisicromía 3. Caracas, Venezuela, 1959 |

He began his artistic career as a figurative painter but quickly moved on to geometric art in the 50s. In those days he would be painting strips of colour, a particularly difficult technique since the colours would mix into one another. He would then use the sides of cardboard, wood and plastic as lines, which he would paint using different colours, until he was forced to stop due to the OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries)’s oil price crisis, and the subsequent skyrocketing of prices of derivatives. Naturally, the artist took this as an opportunity to completely reinvent himself, evolving his techniques and simplifying his workflow by using aluminium. His aluminium-made profiles allowed him the freedom to explore colour in new ways. Since the 70s he’s been working with the physichromie technique, painting on top of aluminium with serigraph. This technique, however, was found to be toxic and work-intensive, and was abandoned in 2000 in favour of numerical technology.

He began his artistic career as a figurative painter but quickly moved on to geometric art in the 50s. In those days he would be painting strips of colour, a particularly difficult technique since the colours would mix into one another. He would then use the sides of cardboard, wood and plastic as lines, which he would paint using different colours, until he was forced to stop due to the OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries)’s oil price crisis, and the subsequent skyrocketing of prices of derivatives. Naturally, the artist took this as an opportunity to completely reinvent himself, evolving his techniques and simplifying his workflow by using aluminium. His aluminium-made profiles allowed him the freedom to explore colour in new ways. Since the 70s he’s been working with the physichromie technique, painting on top of aluminium with serigraph. This technique, however, was found to be toxic and work-intensive, and was abandoned in 2000 in favour of numerical technology.

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez. Physichromie 625. Paris, Francia 1973 |

His son, Carlos Cruz Delgado, told me that a book has been put together containing photographs of the artist’s childhood in New York in the 40s, Venezuela’s marginalized neighbourhoods and its landscapes, etc. There are also photos of the artist together with his colleagues of the time, such as Calder, Soto or Tinguely, exhibitions of which are planned for next Tuesday, February 4th, in New York, and after that in Buenos Aires and next in Paris — certainly something not to be missed!

His interventions in the urban space and in public architecture have given us a whole new way of looking at art, where changes in the viewer’s position or light of day afford a completely different perception of colour and, therefore, a different emotional state. His works are highly acclaimed across the world.

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez. Homenaje a Don Andres Bello 1982. Caracas, Venezuela |

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez. Cromovela 2001, Santo Tirso, Portugal. |

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez. Parque Olímpico, 1988. Seúl, Corea del Sur. |

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Aeropuerto Internacional Simón Bolivar, 1974. Maiquetía, Venezuela |

|

|

|

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Intervención cromática en accesos al Miami Marlins Ballpark Stadium |

To find out more about his work and research, the Carlos Cruz Diez Foundation’s website has plenty of information on his full range of works.