- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

Air, fog, mist... An Apollonian veil that covers everything with an Olympic brightness. Within white itself is the search for peace, purity and spirituality, evoking a world beyond reality. This is encapsulated in the pictures by Fernando Manso.

Fernando Manso (Madrid, 1961) began as a photographer in the advertising world (1990-2007). Thereafter, and until today, he developed autonomous work focusing on the organization of exhibitions and book publishing. Among other works, he has published Madrid for the Editorial Lundwerg, with a personal and previously unpublished insight into the Spanish capital that is now in its fourth edition; or Spain, to discover special landscapes of our country and is prefaced by Antonio López. Precisely this artist referred to his work with romantic overtones: "There are many ways to represent the light, and his photographs remind me of Caspar David Friedrich, as they are touched by this evocative spirit of German Romanticism; his temperance reconciles the tumult of idealism with a beautiful harmony and serenity". His next production, on which he has spent the past few months, is centered in the Gardens of the Alhambra.

The work he now presents, Blanco, reflects the world of this photographer of beauty and sensations. He longs to reach this world through each of the moments that he wants to perpetuate. Traveller and seeker of beauty, two decades ago he began his career through self-teaching, but with an aesthetic sense from a childhood overflowing with art. Water is a constant in his work, in a state of snow, ice, fog ... as the essence of life.

The photograph has the power to capture the reality of a moment that will never be repeated, living and eternal return. Heraclitus said that everything transforms through a continuous process of birth and destruction from which nothing escapes. Manso's images have succeeded in this. His photo's belong to a world where everything is repeated, because it fixes the instant in an eternal present.

The effect of colour on our perceptions and behaviour, or how we are affected by them, is something that Newton, Goethe and Schopenhauer and others tried. The colours awaken different interpretations as our subjectivity or our stimmung. These white images convey loneliness, absence, nostalgia and fantasy. They are poetic scenes belonging to a oniric world.

His photographs tell stories, convey emotions, make you dream, stimulate our imagination. Its author, a tireless observer, stoically waits for the moment he feels the urge to capture the fleeting moment in the vastness of eternity to tell his story, which he feels is their own. His identity is in each one of them. The observer, in turn, enhances the work with their multiple interpretations. That is what art is all about, how the viewer is transformed by it.

Poet of light, of the intense gaze, Manso is a witness and discoverer of beauty, sounds, textures and gestures that make up the "painting" that he will create. He creates his images with a very fine line that separates his photograph from a painting. These white images not only invite you to look at them, but also to think about them. They have a lot of mysticism, pilgrimage to the light of reason and truth. Light and white are linked to beauty, that for which he longs so dearly.

Craftsman of bellows and plates, grain and haze, rust and light, he throws his plethoric images of romance, fantasy and melancholy, as an allegory for the essence of his soul. Enter into his pictures, remain in his space, where the shadow and light fuse. Silence and whiteness, as if the notion of time is lost, we are impregnated with the peace and harmony that is projected. Coming from a serenity that is eternally unchanging.

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

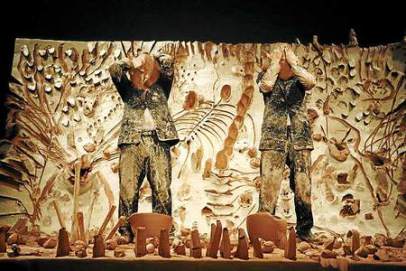

Both the Island of Mallorca and circumstances have led me to a meeting with Miquel Barceló during which I had the opportunity to discover more about his life and work. The visit began in his ceramics workshop, La Taulera, and ended in his home and workshop in Farrutx.

“Have you seen these black pieces? They are smoky” the artist says while he shows me the study. “I leave them there in the chimney so the soot covers them and then we attach cobwebs and everything. I really like it. The clay I use is from just near here and it ends up being this bread-like colour, as you can see, which happens to be the colour of Mallorca cities”.

The workshop has a certain incline: “The soil went in through there and comes out in the shape of a tile or something. Claude Parent came up with a theory about oblique architecture that goes back to the 1960s, because obliqueness always forces you to be in action. If it is horizontal you’re stationary, if it’s oblique it’s dynamic. It’s fun to live in an oblique house because if something falls off the table it will roll away. It’s a very interesting philosophical concept”.

Elena Cué: Will this ceramic piece be black?

Miquel Barceló: I never know what they will become.

E.C: When did you begin creating black ceramics?

M.B: I started to create ceramics in Africa and black ceramics not so long ago. First I began making smoky paintings, because a way to destroy the work I throw away is by burning it. But given that ceramics can’t be burnt, we crush it to make grog, which is ceramic dust, and then we turn it into something else. Regarding the paintings, it’s strange because I wanted to destroy some by smoking them, but as I started to scratch them, they turned into something else. The same happens with ceramics; they turn into objects. Look at this black cut, it’s like firewood... I hate these bright and colourful ceramics. I like ceramics from two thousand years ago, the Andalusian ones. In fact, in general, there is very little I actually like about ceramics. I like some of Miró and Fontana’s work in ceramics, but I think contemporary ceramics are horrible.

E.C: I visited the Caves of Drach...

M.B: The Caves of Drach, the Cathedral of Mallorca and the bottom of the sea are definitely my favourite places here.

E.C: Have you seen the girl’s hand that was recently discovered?

M.B: Yes, things appear constantly. Here they analyse a coprolite and say, “it’s 50,000 years old”. It’s a race to see who has the oldest cave, it’s stupid. Altamira is wonderful but there is nothing even remotely similar to Chauvet. It’s an absolute jewel; the oldest and yet the best, it’s ironic.

E.C: I remember you said Chauvet was one of the most inspiring aesthetic experiences of your life.

M.B: The Chauvet cave has more to offer than Altamira, Lascaux, or any other. I have seen them all so many times, it’s almost a profession. There is something about this particular cave that goes beyond what we are able to understand. Yet in the Altarmira cave, we not only understand how it was built, but very much the reason why. Instead, in Chauvet, there is something that escapes us; a relationship between man and his paintings that we also cannot grasp, that sort of deep empathy with the animal. The difference in the animals’ morphology is amazing. In Lascaux, one bison is every bison; they even used a template, which is very modern. They had a piece of skin to draw the outline. When they paint a bison, it is a generic bison. On the other hand, in Chauvet a horse or a lioness is unique to the point that there will be no other exactly the same as it. So unique, you could even give it a name and surname. It’s like Rembrandt’s group painting, in which each character has a life and parents and children, it is amazing. Chauvet is the other example of a culture we know nothing about. And it is very likely that their epigones can be found in the caves of Altamira.

E.C: Why the obsession with caves?

M.B: There are many here; for me it’s like going under water. It’s also the place where light is made. The cave creates things, it’s always fascinating. It’s also the place for burials and reflection. Where I live there is a cave and this was a very determining factor when I decided to buy the house.

E.C: I can see your last paintings are not so matter-orientated.

M.B: I don’t like my work to be particularly matter-heavy. I mean I do really like Velázquez, and his work was like that, but it’s not so much because of the amount of matter used, but more about the perception. With Goya or Velázquez, it is not the amount of impasto but the evidence of the impasto that’s important in each brush-stroke, meaning it is not an abstraction, it’s a physical fact that makes the difference between Velázquez and Goya. That kind of physicality of things is very much what characterises Spanish painting. Even painters like Meléndez or other painters that seem flat. Rembrandt began painting like Meléndez did for his whole life, and then he gradually started refining and concentrating... Like Giacometti, he came to the conclusion that all human figures converge at the nose. It’s like a pyramid, they said his paintings could be hung from the nose because he used a lot of impasto on them, poor Rembrandt. And Meléndez was a frustrated figure painter, he always wanted to be a realist painter, a portrait painter, he was trained for that. He was the son of painters and he was trained to become a leading figure. But poor Melendez never managed to be a realist painter and he had to paint still life his whole life. There are hidden figures within the still life paintings which make each tomato like a portrait and its life begins on the edge of the table. All of his paintings stand out because of this edge, at the beginning they are clean and in the end he paints the bumps and scars he has suffered throughout his life, as if he was painting all his wounds.

E.C: Fascinating...

M.B: I have read a lot about the life of painters, I enjoy it. The only place where I always feel affinity with people is in the Museo del Prado. When looking at the paintings, I feel there are things we do share. I go there very often, whenever I can. It is my favourite museum. It’s the great painting museum. I also like the Museum of Cairo, it is wonderful, but El Prado is the best painting museum in the world. The Louvre Museum is a great global museum, but El Prado is the painting museum and baroque painting museum. It’s traditional and of a private culture.

E.C: There is another, more beautiful Africa, but you chose one of the poorest countries in the world, Mali (Dogon Country). Arid soil, full of dust, desert, termites, illness, death... Why?

M.B: I didn’t choose it, it chose me. First I was going to cross the desert, because I had been living in New York and I had been painting these white paintings and I did not quite know the reason why, a kind of need for cleanliness, to renovate something. I also wanted to get rid of the burdens I was carrying. So I went to the desert without really knowing exactly where I was going, a trip with Mariscal, so then we went to ask a guy who did the Paris Dakar for advice because I didn’t even have a driver’s license.

E.C: Pure adventure.

M.B: Just imagine how daring; off I went in a Land Rover I had just bought. I usually do things this way... They told me to be careful with the dust, which could even get into a can of sardines, and I thought it was sort of a metaphor, but it turned out it wasn’t. It was a fact, a reality. The dust got into everything; in between papers, in the paint... At the beginning I fought against it, like the termites, but in the end I incorporated it. It was like a gift, it improved everything. And my work had meaning there. We went to Gao, to Timbuktu, next to the river. It was a place of great beauty with a pink dune, which is a sand mountain where couples go to to see the sunset. So I started painting, not like in New York, Paris, or any other place. Painting a big painting on the floor didn’t have any meaning. I started drawing at the market, like when I was 12 years old; I started to draw people and sand. It’s like being in space, painting without gravity - like drawing nothingness. Spaces without a horizon are pure light. I started the sketchbook and the watercolours and then I got to the Dogon Country and I was fascinated. To begin with, I only knew its statuary because you can find it in museums. It didn’t even interest me that much until later on when I got to know it. Then, in 1991, the Dogons built me a house, but there was a coup and a revolution, so for a month I went across the Niger River in a canoe.

E.C: Was it dangerous?

M.B: Well, there were soldiers, armed Tuareg... The canoe was easy to spot, it was different from the rest, because I built it to paint on it. It had a table with sides. I painted the front and back of the small boat and we sold it there for 300 Euros, the normal price for a canoe. When I sold it, I wondered if there was some smart-arse who knew my work and maybe I would find it later in Paris. But it ended up in Gao, old, and I’m happy, it was good that no collector had found it. Anyway, later the Dogons built me another house in the best place, next to a water fountain and some caves, a fantastic place, which is still my house.

E.C: When listening to so many experiences one of your profound remarks comes to mind: “We paint because life is not enough. Regardless, life is enough here. It is almost excessive”. Did time slow down there and was life so cruel that it became excessive?

M.B: Everything is extreme in Gao; happiness is extreme and pain is extreme, boredom, everything is extreme. Everything is lived intensely. If you’re sick, you almost die, everything is intense. That is why you miss it so much later. But you are also spending such a long time just sat waiting because it is so hot. Sometimes it reaches 50 degrees, and you have to wait until the temperature cools down. By nature I’m not patient at all, but I think in Africa I learnt a lot about this kind of patience.

E.C: What did you do during the time you had to spend waiting?

M.B: I wrote, drew, I was able to read, think or do nothing. But I remember when the typical policemen would stop you and ask for money if you were a white person. At the beginning I bargained but then I learned the rules. I learned that if the policeman didn’t have weapons, or a cell phone, I’d wave at them and keep going. In Africa they are so polite that you say “Salam Aleikum” and they reply, and then they whistle at you to stop, but you are already a hundred meters away. So I decided- if they have a weapon I’ll stop; if they don’t I’ll keep walking.

E.C: Were you able to remain patient?

M.B: The first time I crossed a line that they had painted on the road behind a corner, I got out of the car with my friends, I got the teapot and mats out and I started making tea. They kicked us out immediately. When they see you’re not in a hurry, they kick you out. They know how to bargain with white people in a rush, which almost all of us are. White people tell them “I have a flight tomorrow” and they think great, I’ll get a lot here. The thing is we are transparent.

E.C: What do you miss most about Mali?

M.B: I think most of all I miss the laughter. Every single day I would be among friends and we would laugh so hard we would cry. Literally around fifty people, both men and women, used to come to my house and drink tea or beer and tell stories.

E.C: And what were those stories like?

M.B: They were their stories. They retell the same story they have told you fifty times before, but an improved version of it, it is about constantly making it better. I learnt this from Paul Bowles in Tangier, because he transcribed the stories from the market, from the illiterate storytellers. The stories were published in Anagrama.

E.C: Don’t you have his book collection?

M.B: Yes, I have his book collection. In his older years we became friends, he was 80 years old. He was the only European who had come to live in Africa at that time. For me, he was a role model; he was not the typical guy who goes to live in Bora Bora. Like me, who went to live in Dogon Country... Who decides to go and live there? A successful and wealthy guy goes to live in other places. Francesco Clemente went to the south of India, near Goa, he was more chic. Dogon Country was one of the poorest.

E.C: I thought it was more a search for purification?

M.B: I was not looking for that, I liked it so much that I stayed. I think I needed to find a balance.

E.C: Do you go to the extreme to find that balance?

M.B: Yes, I have a tendency to do that. But there I also found something no other place had, this Dogon wisdom and this way of being in harmony with things. Everything makes sense there, you never know if it has been made by man or by nature, it has a perfect harmony which is very hard to find. And I liked the relationship with people. The same happened with food, which is very sober and of an absolute simplicity. Mali’s food is very tough, there is only grain, it is like Neolithic food, but you get used to everything. I think it suited me well, because I was afraid of becoming a cretin and not realising it, seeing that I had reached success at a very young age. Cretins are the last ones to become aware. In art, it is easy to lose tension and my friends were dying during all these years, Basquiat and the painters from my generation.

E.C: You also have a lot of merit because you were involved...

M.B: In things that are not very healthy.

E.C: Yes, but there is more merit to sever ties with everything, friends included...

M.B: It was the 70s. And between one day and the next I think I realized I had this great power to walk away. In the past I didn’t know if I was going to be able to. I knew it when I did it. It is like the chapel of the cathedral, I found out I could do it by doing it. I think it is like that, you know things when you do them. Each painting is like that. So if you fail, nothing happens because you start again. Now that I think about it, when I was going to work in the Cathedral I didn’t know quite how I was going to do it. I knew I wanted to make a great cracked ceramic, divided naturally. I didn ́t want cut tiles, and somehow I had the need to do it, I had the confidence that I would do it.

E.C: This experience was similar to the Chapel of the United Nations, since it took you many months to find the appropriate material.

M.B: It was painful. From September to February. We had to throw everything away, and I had to fire a whole team.

E.C: And the French students?

M.B: I also had to fire them and I still don’t talk to anyone. One of them came to me with some sort of papier mache proposal, like a decoration. I told him: “No, I want to make a cave of painting, I do not want to decorate...” So I started again but it was very complicated and I was lucky they didn’t fire me. Working with the pressure of a contract which is about to expire and with penalty for delay. They reassured me, but the United Nations needed this hall.

E.C: Did they understand it?

M.B: One day I wanted to explain properly to “the ones in charge” (I don’t want to mention names), what was going on. So I used an inappropriate metaphor related to suicide and said, for instance: “Look, for someone like my grandfather suicide was not an option; it was forbidden by the Church, by his philosophy, it was anything else but that”. For me and for our generation since Nietzsche, suicide was an option. For an artist failure is an option, that is, I never have the guarantee that a work will succeed, because if I had it I would never do it. Today you have seen the shattered pieces in the workshop. Each of them was an entire day of work and that was a failure, and this other was a technical failure, because of humidity. So, whoever told it, made a summary about the suicide thing. Perhaps he thought there was a risk of me committing suicide and told me: “No, calm down, take as much time as you want”. He thought I was going to hang myself from a stalactite, it was very funny.

E.C: Art: how much is pleasure and how much anguish?

M.B: Anguish is a work tool, it goes with my work. Anguish is like another brush, it is implicit. I don’t find a way to avoid it, sometimes you go beyond it. And also there is great pleasure, of course. The evil grace is that you’re never able to repeat the same pattern. Sometimes it turns out very well, and I go back to my workshop wondering if I step on the same stones, if I do exactly the same thing, it will turn out fine. No. Never.

E.C: Why?

M.B: It is a miracle that can never be repeated in the same way. Paradoxically, it will be repeated in another way, the complete opposite. It is about accepting, about accepting right and wrong just as it comes. The banalities that are always spoken are true.

E.C: Mali, Nepal, Japan, Sicily, Paris... You are a cosmopolitan man, some kind of migrant in a strange land. Why the need for a nomadic life?

M.B: It must be a result of the isolation. I understood that the first time I lived surrounded by water, I became claustrophobic. I have always seen the ships and wanted to be inside, even though painters are very sedentary.

E.C: Also as a source of inspiration?

M.B: Yes, after Mali I needed something at this level. That is why I went to the Himalayas, because I thought there was something there with a similar spiritual level to Mali, something I had not seen elsewhere. I went across the mountain range and I’m going back this summer. Also because I like the summer less here and I like August there. I have always thought that painters should constantly invent the techniques and the tools, we don’t have to assume anything. We have to reconsider it. In the Himalayas you have to reinvent how to work. Last time, I was working with parchments and I took some from here with me. I was working with them in monasteries. It is funny because the monks told me I was responsible for the animal, because each parchment was the skin of an animal. It is not a sin, you are responsible. It is nice: I had a little flock with me. Now I think about that with any piece of fabric, that you have to be responsible. It is a responsibility to place something new in the world; it does not matter if it is just a pot.

E.C: Mali’s situation is sad...

M.B: Mali has left a mark on me forever, without a doubt; in my work and in myself. But I already knew it was going to end badly, because I saw it coming. Even though I didn’t think it was going to end up quite so badly... Well, I thought my children would keep on going because they had a lot of friends there. Hopefully this will continue for them too. They meet there to make collective works. Since I no longer take part in these activities, I try to help with other things. It is fine if my children inherit this responsibility to try and improve, but these are things one cannot speak of. You do them but then don’t talk about them.

E.C: I’m curious to know what happens inside the artist at the beginning of the creative process. The transformation from impulse to sublimation. You have mentioned that your painting is an activity that is, to some extent, sexual.

M.B: Yes, yes, everything is very sexual. It is clear. When I see the ceramics, it is so evident to me that sometimes it was almost ridiculous for me to emphasise it. Like in these vases of female genitals. In Palma Cathedral I looked at it with a psychoanalyst who is a friend of mine and I explained to her how some fish are like male genitals, and the fish open like vaginas and anuses. Our view of the world is a lot like this.

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

With his face resting on the window, Alessandro looked at the Starry Night who aroused in him an inexplicable craving for remote and beautiful things. The orange trees and magnolias, still blooming, gave off strong aromas at that time. In the background the dark masses of straight olive and acacia trees marked the limit of Beccarisi Villa, the luxurious Sicilian villa of his friend Giulio where they would also spend that summer. Alessandro recalled his previous visit and finding that secret hidden corner at the end of the garden near the greenhouse, where one night he heard hugs and kisses in the dark as the moonlight created the illusion of fantastic figures fluttering behind the glass between whispered sweet words, interspersed with sighs and sudden silence. As the fermentation of the fertile and burning ground, there he also experienced the mysterious sound of the eternally creative and destructive life.

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

"Pleasure is even deeper than the pain.

The pain says: Pass!

But all joy wants eternity.

It wants deep, profound eternity! "

Nietzsche, Said by Zaratustra

With his face resting on the window, Alessandro looked at the Starry Night who aroused in him an inexplicable craving for remote and beautiful things. The orange trees and magnolias, still blooming, gave off strong aromas at that time. In the background the dark masses of straight olive and acacia trees marked the limit of Beccarisi Villa, the luxurious Sicilian villa of his friend Giulio where they would also spend that summer. Alessandro recalled his previous visit and finding that secret hidden corner at the end of the garden near the greenhouse, where one night he heard hugs and kisses in the dark as the moonlight created the illusion of fantastic figures fluttering behind the glass between whispered sweet words, interspersed with sighs and sudden silence.

As the fermentation of the fertile and burning ground, there he also experienced the mysterious sound of the eternally creative and destructive life, the grandeur and beauty of the pleasure of life that continued even when the lovers parted, his shadow touched hers as in an embrace under the deep blue sky of dawn, which began to dim the stars. The memory of that summer full of light had continued in his soul, more alive than in his tumultuous present.

"The experience of transience and incessant short living", Giulio had said at one point in the conversation over dinner. "To know that we lose ourselves as the wind does, and we flow like the water of a river. The perception of this continuous flow, when you think about it, does it not raise an inevitable resignation and anguish? Time is the instrument of death, the last structure of a lost experience. How many things there are that we will never see or know! "

It seemed he wanted add something else, but he stopped.

"What then is the continuity?” Alessandro had immediately replied, "Is there any point in the thought of eternity (Ewigkeit)? Do you think there is no place or experience where the agitation of change is calmed and we pick up what we have lost? I think it is not a mere illusion of the poet who says:

"I know one thing there isn´t. It's forgetfulness.

I know that eternity endures and burns

the precious and all I have lost

tonight, this moon and this afternoon ".

"However, what place could be that of permanence, even more, of eternity?" Alessandro continued thinking later on. "The days tend to become equal in the memory, although not all the same. And the most common life among men is that of a relentless nightmare, a stubborn routine with a dispensable story, a set time and the wait for obscurity to offer us one last dream without memory. Was Giulio right? Life is nothing but the desire of a dreamt destination longing to become real, a tale told by an idiot in which the protagonist awaits his end at any moment when everything would be about to begin. How to understand time as a mysterious cross over, in each moment, of change and eternity?

The afternoon was burning strangely in the clouds, as if behind them an ocean stirred into flames, a divine fire. Shaken by his own words and thoughts, he left the garden despite the intense heat and walked along a stretch crop towards the city. The grass between the vineyards was dotted with small flowers where above them yellow and white butterflies fluttered. The harvest in the fields was tall. Each stem was bent over the earth bearing fruit. Under the trees, sitting on the grass, a group of peasants rested a moment from the hard work of mowing and greeted him taking off their hats, as he passed by. Further, in the pool, some children were bathing across the sparkling waters, reddened by the sunset colors. They slid along rocking to the rhythm of the gentle breeze, and above the waters the shadows of palm trees also rocked, while on the other side there was a murmur of young voices and laughter. The still air was only occasionally interrupted by the lure of a bird.

"There are many things we will never know", he said to himself. "Maybe that's why it is desirable to even forget what we know, and be content with seeing the world in silence."

He continued his walk absorbed by the landscape, moving from image to image through a tenuous game of ideas and rethinking that which troubled him:

"The certainty of the end encourages seeking solace in the pure present, satisfying the intense enjoyment of the pleasures in life. Thus, the wait has been enriched by the remembrance of the idealised past, reconstructed to suit our most beautiful dreams. In its absence time goes by without thinking. The human soul does not reveal its mysteries. When you ask it, it remains silent."

Without being able to unleash this reflection, again a dull breath disturbed the peace of his rest. He had reached the shore and saw, buried in mournful resignation, the area in which daylight no longer shimmered. The sun had set and it darkened over the city. Everything became quiet and peaceful in that cramped and hot afternoon, where the first indoor lights shone while a big white moon lurked in the sky. He crossed the fishermen neighborhood and as he walked past a tavern, he heard music, songs and the sound of a big party. He entered and went to the bar while the musicians played a light rhythm and a young woman prepared to dance. Her hair glistened with perfumed oils; her body radiated party excitement and the smile of her mouth revealed sensuality of laughter and kisses.

She was dancing barefoot and entranced, as if embracing invisible bodies that no one saw, as if to kiss lips that were parted and bent over hers lustfully, as if caresses were to be spilt all over her body and she would enjoy those invisible bodies in unusual raptures of her dance. Maybe she lifted her mouth towards precious and sweet fruits, and sipped hot wine when throwing back her head and her eyes full of desire edging her head high. And so she continued moving alienated, surrendered to the irresistible power that dominated her.

When the music ended the girl stopped and stood in front of everyone. It was the most vivid expression of pleasure, a beautiful single flower that had just opened while a multitude of eyes looked drunk with wine and sin. And while Alessandro watched, he had an inspiration: Dancing! The relationship of life, whose substance is time, why not knowing what is called eternity is only understandable from the ancestral and Heraclitean ring symbol. The succession of things and worlds is nothing but a dance, the perimeter of a circumference, a wheel that rotates on its axis, a cycle that repeats forever.

"Only art instructs us about this mysterious relationship", he began to reason, "Art simulates stopping time, bringing together the gerund of living and seducing with a look of beauty. If faces go as dances, art sets our face and gives back the image of our own face. This transformation simulates the time in "eternity", and allows man to follow the old Apollonian advice: 'to know oneself'. Our face, being familiar but unknown at the same time, looks at us from the mirror and shows us all of the strangeness in ourselves. It is only prudent to go with what is shown in the mirror and its indefinite multiplication of things."

When he gleefully recounted his discovery to Giulio, he was pensive and after a moment he said:

"Do not be naive Alessandro. But what power does the art have versus the obsolescence of reality and its spectral reflection. It does not answer the philosophical question that leads irresistibly to the connection of time weaving and unravelling. The life of man is the fate of a caged lion repeating its monotonous circular paths without knowing that there are meadows and mountains outside of its path."

"Indeed, Giulio, that's how it is", I replied. But because of knowledge of such a hard fate it would be unbearable. That is why the Gods, pitiful upon us, grant us the grace of oblivion, the consolation of not knowing. What it is an unknown destination? The children´s games of freedom. The novelty fits unpredictability as well as the consequent openness and incompleteness.

The destination is frozen time, and time is a corrosion of that destination. This will, therefore be hereinafter the motto of my life: "Convert the outrage of the years in music, in a rumour, in a symbol ".

Alessandro finally felt rejoice in solitude and calm, and watched for hours and hours for the vibrant sky to clear as he was dominated by inexplicable thoughts. His eyes were intoxicated with the bright colors of the branches on which the rays of sunshine poured. Silence welcomed his dreams in the lonely twilight hours that followed then when the night slipped into his room and stood before the window lost in the shadows. The air was again filled with the intense perfume of orange blossoms and roses protruding from the garden fence, as well as mingled with the scent of jasmine and honeysuckle that climbed hugging the tree trunks.

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Sometimes it happens. Some exhibitions like a hit of emotion. As with the deepest experiences of love: irrational. And this time it happens to us. We leave the traffic of Recoletos, climbed the stairs of the old palace of Madrid, headquarters today of the rooms of the Mapfre Foundation: Sorolla and the United States. Room 1. Dark and small inside: El Algarrobo welcomes us, as only he is illuminated. A medium format frame, landscape, far from the monumentality of Sorolla. We remember how to enter directly into the blue sea that reflects the sapphire blue Mediterranean, in the light of noon. Bright blue, with its minimum stroke of a white spatula forming a wind sail, Sorolla's characteristics.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

"I wish I was not so excited,

because after an hour as today, I now feel undone,

exhausted, I cannot take more pleasure, I can´t resist like before ...

It is that painting, when he feels, is greater than all;

I said wrong: what is natural is beautiful "(Joaquín Sorolla)

Sometimes it happens. Some exhibitions like a hit of emotion. As with the deepest experiences of love: irrational.

And this time it happens to us. We leave the traffic of Recoletos, climbed the stairs of the old palace of Madrid, headquarters today of the rooms of the Mapfre Foundation: Sorolla and the United States.

Room 1. Dark and small inside: El Algarrobo welcomes us, as only he is illuminated. A medium format frame, landscape, far from the monumentality of Sorolla. We remember how to enter directly into the blue sea that reflects the sapphire blue Mediterranean, in the light of noon. Bright blue, with its minimum stroke of a white spatula forming a wind sail, Sorolla's characteristics. It is the sea of Javea in 1898, with its soft pink coast in the background. The protagonist is an old carob tree nearby; the Eastern Mediterranean, with connotations of absence, which leads to the baby-boomers who, in the absence of chocolate, enjoyed sucking their sweetpods as a treat.

In its twisted trunk there are shadows of the Sorolla palette; short brushstrokes and ochre material, grey and black with contrasting blue-green fleshy leaves, with a prickly row of pears left behind, in the sun. And that ends in a white washed wall with a white as hurtful as it is cheerful.

The shadow of carob is home to dozens of sheep and goats. The siesta. Dead spots and holes from the sun. The radiant light of that sea. We almost anticipate a fly buzzing, the rattle of sheep, a mixture of the smell of the sea with a herd and a tree, almost the exact temperature and warmth of this Levantine landscape that transports us with a myriad of sensations.

We approach to read the label of this picture. Under the title and date, provenance: Private collection, USA.

Sorolla: El Algarrobo, 1898.

We turn around to its companion picture: Port of Valencia, this time the Cincinnati Art Museum. Rarely have we seen such audacity in a painter to capture light on a basket or white hat. So much so that the elements, in this case the basket, or wide-brimmed hat, are nothing more than an excuse, a shield emanating light. It would seem that it forms with light. It's a classic scene in Sorolla: the active sea, the harbor, fishing. The boats, with children jumping into the water from them. We immediately think of many other targets: the ones of Zurbarán, more mystical and conventional, in their tablecloth fabrics or chasubles dense thread, also in the thick strokes of Rembrandt as light bulbs that light up the darkness. Even in Velázquez or in some Venetian painters of XVI. They have nothing to do with the message of these targets coming out of the sun, with light, warm air turning to shades that almost introduce scents: the vanilla wafer, summer, the coast, the west, to joy ...

What have these two pictures in common next to the other two -´Another Margarita !!´ and Los pimientos- hanging on the walls of the first room? Sorolla always felt a transnational painter. These four pictures show how before the arrival of the painter to the United States, for his major exhibitions of 1909 and 1911, some of his works already belonged to American collections. Port of Valencia or El Algorrobo were purchased through European dealers who acquired works in exhibitions in Paris, Munich, Berlin and London and are the preamble to what Blanca Pons-Sorolla, curator of the exhibition, comes to announce as the theme of this exhibition.

After the retrospective of Sorolla in the Prado Museum in 2009, it is now the Mapfre Foundation which brings us to the moment of triumph, in the middle of the fullness of his work. Sorolla in the United States. For this to be together, for the first time in Spain, a group of works, many never seen here, which were exposed by the painter in his American samples and purchased by collectors and museums in the United States.

Sorolla: Saliendo del baño, 1908.

Joaquín Sorolla was born in 1863 and died in 1923, 60 years and five months old. We must understand what the political and cultural context in which the painter´s life goes through to assess precisely the merit of his American triumph.

Sorolla's life covers the period of the Restoration and the parliamentary monarchy of Alfonso XIII. It is a stage of political stability in Spain, so it is also in the economic field. However, a deep rift divides the country: political Spain on one side and the royal Spain on the other. The field remains stuck in stagnation, while an oligarchic bourgeoisie consolidates. Both are faithfully portrayed by Sorolla.

Furthermore, the settlement of overseas empire occurs in 1898. The country is almost reduced to its present limits. This has a direct impact on the intellectual movement that leads to a controversy which arises both in the field of literature as in painting and other visual arts. That fracture divided Spain in what came to be called the black Spain (term coined by the book by Emile Verhaeren and Darío de Regoyos, 1899) faithful to a nation at the crossroads, anchored in its medieval and dark roots. A Spain guided by artists like Ignacio Zuloaga to Julio Romero de Torres, also by the great authors of 98, Unamuno, Valle-Inclán, Baroja ... Faced with this darkened Spain, a white and bright Spain shone, born with the joy of living in the present. Next to this Spain were other painters apart from Sorolla as Hermen Anglada-Camarasa or José Pinazo.

In the field of painting, which is the present one, it is curious to know that this controversy even affected the world of colours. In Sorolla, all of his energy is manifested in the power of the chromatic material, in full thick brushstrokes with thousands of combinations of tones which advanced the joy of life. While Zuloaga y Romero de Torres belonged to the current Unamuno who, in his denial of any substance sensuousness as art, rejected all the elements that confer greater physicality to a picture, by oil painting or colours. For him only grey would fit "because the grey tends to behave like a vampire of the colors, because when mixed with them it is in charge of sucking the blood, the life strength, up until emptying themselves." It is in this context that, for example, imagine our Valencian painter, easel in hand, touring Spain, by painting on giant canvasses, full of strokes and patches of colour, noise and optimism to be hung in a Hispanic Society at farthest from noventayochista pessimism.

Sorolla: Dancing in the Café Novedades of Sevilla, 1914

Nothing more out of this first room we finally start with the enormous Sad Inheritance! (1899). Sent to the Universal Exhibition in Paris with five other paintings, the jury awarded the Grand Prix Sorolla by all, but especially for this work here, within these walls, it seems drowned between a floor and a ceiling too close for her. We think it is the only sea painting of Sorolla where the beach is pure melancholy. It's not the bright and cheerful July or August light, nor the golden September; it is a cold light, like of early June. The sea, even the waves and sand, blue and white, seem to have been mixed far too much on the palette with a huge splash of priest's cassock bitumen color, which also makes his hard profile stand out. The rest, those emaciated young are the only bodies of children that Sorolla painted in the sea whose skin is not covered by this transparent, cheerful and slippery film that is the brightness of salt water and what makes it something like metallic fish reflections.

Sorolla here becomes austere, even in the amount of material used in the stroke: dispenses with all sensuality abuse thick patches of colour limiting to almost scraping with the spatula. Returning to those poor children head down with shaved hair and those who do not paint eyes, to the ephemeral misery in their time of joy. Plunging themselves into a water cooler than ever. In a sea that almost becomes the Atlantic.

Source of picture: Purchased in 1902 by J. Vidalin NewYork.

Sorolla: ¡Triste herencia!, 1899.

SOROLLA AND HISPANIC SOCIETY.

The ground floor of the exhibition is dedicated to the two great patrons of Sorolla in the United States: Archer Milton Huntington and Thomas Fortune Ryan.

Sorolla: Thomas Fortune Ryan, 1913.

Huntington founded the Hispanic Society in 1904 to promote Hispanic studies and bring the American public to the Spanish culture. Not only in relation to painting, but also with literature.

In 1909 he organised the first major exhibition of Sorolla in the United States, in the rooms of the Hispanic Society of New York. It was a resounding success, both in sales and assistants to the exhibition, as well as the support from a glowing review. This first exhibition later travelled to Buffalo and Boston where they were received with similar enthusiasm. Sorolla's second triumph came two years later in 1911 in Chicago and St. Louis.

As a result, Huntington entrusts "the work of his life": fourteen panels to decorate the library of his headquarters in New York. Sorolla took only eight years to make this request: from 1912 to 1919. Shortly after completing the last canvas, and probably due to the superhuman effort he performed, he suffered a stroke and in 1923, three years after, he died.

When in 1926 the paintings were finally hung on the walls for which they were conceived, both in America and in Spain this fact went almost unnoticed, fading between the press and criticism so far from the overwhelming triumph of Sorolla a few years before.

What had changed over the eight years in which Sorolla had covered the Spanish geography even painting it in the wake of the success of the exhibitions of 1909 and 1911?

There are two facts that spun the sensitivity of the American and European companies. First of all, the First World War, but above all, a crucial event in the development of the fine arts: where in New York the Armory Show took place and made its way, blowing all the locks on all the doors, the avant-garde spirit.

Armory Show, English name of artistic exhibitions held in the armory of the 69 Regiment of the National Guard in New York, is the term that refers to the International Exhibition of Modern Art that took place between February 17 and March 15, 1913. This exhibition was a turning point for American art focusing it toward modernity and distancing the hitherto dominant academicism. It brought together some 1,300 pieces that roamed the development of contemporary art with representative works of Impressionism, Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism and Fauvism.

Apart from the density of ideas that characterised this movement, there is one that sums it up well: the forefront is the prioritisation of the discourse on the figure.

The artists who moved around the 1900s, we would say between the last quarter of the nineteenth century until 1914, did so shuffling the dialectic between discourse and figure, looking for a communication between them. But from 1914, speech, meaning, sought independence from the matter that constituted the body: the soul tried to become independent of the body that gave life and consequently the fine arts wanted to separate from the material that it conformed. The basic idea of departing was replaced by the will of transcendence: of intangible meaning.

The center of this edgy hurricane was Marcel Duchamp and his obsession with getting away from plastic sensory.

In short, the ideas were interesting; painting now looked at the service of the mind and the antisense speech that led to the vanguard collided head-on with the painting of Sorolla, essentially sensory and sensual. Sorolla was obsolete.

It was not until the XXI century where the anti-vanguardismo shows its breadth when the figure and fame of Sorolla are returned to the place they deserve. There are 20 paintings in the collection of the Prado Museum.

VALENCIA BEACH, THE PORT, CHILDREN IN THE SUN, THE LANDSCAPES AND PORTRAITS OF CLOTILDE AND ELENA THAT FLOOD NEW YORK ...

Sorolla: Running on the beach, 1908.

"The air was impregnated by miracle everywhere. People quoted the number of visitors and he continually had in his mouth the words" sun glare. "Never had anything like that happened in New York. The ohhh and ahh´s misted floor tiles, cars jammed the street. Portrait orders poured in. Photographic reproductions were sold in unseen quantities. And through it all, there was our little creator. Sitting quietly, overwhelmed but not cocky, while I would translate the waves of enthusiasm from the press. "

(Letter from Archer Huntington to his mother , Arabella Duval Huntington New York, March 1909).

And yes, with this letter from his mother Huntington we understand part of the revolution that Sorolla created in New York in the beginning of the century, flooding it with the Mediterranean light, of the joy of this mysterious inland sea.

In a sort of time warp we imagine ourselves converted to American viewers, moving for the first time, stunned amongst the paintings of Sorolla.

How would we react seeing ourselves surrounded by scenes of sea and beach - girls with pink dresses and loose buns running hand in hand, jumping on their reflections that turned into torrents of colors and light. Persued by the naked body of a child, in a jump, after a blue and violet sea crossed by horizontal waves which look more like grins, with baby teeth and screams rather than foaming curls? Would we notice, in the winter across the Atlantic, how light brightens the colors to its fullest, irradiating them until they are put into our thick coats closed with buttons and filling them with a feeling of warmth and comfort which the paintings of Sorolla always give? Accompanying this canvas, Running on the beach (1908, bought by E. Huntington, in New York in the exhibition, 1909) a series of preparatory drawings on paper where the spirit of Sorolla already announced the use of charcoal and graphite sculpting the folds of the robes of the girls almost as if they were a korai of classical Greece, defining his arms, organising her hair, off the extensive patches of bright pastel white are those that breathe life into the figures and faces of girls.

Sorolla: Girls running III. Study for Running on the beach, 1908.

"THIS ARTIST OF VALENCIA HAS FOUND HIS TREASURE IN BLUE WATER. BUT THE DOMAIN OF THE SEA HAS NOT BEEN ACHIEVED BY JOAQUÍN SOROLLA IN ONE AFTERNOON. HE IS SAID TO HAVE a BROKEN ARM DUE TO ROWING AND A SUNBURNT FACE"

(Juan Ramón Jiménez)

Much in the style of Sorolla , there is a lot of his personality: vital and passionate, just painting conceived as a vehicle for his feelings and his way of seeing things. The painting was his life and in that sense there was dissociation between life and work, between man and the artist. I felt things directly, away from the depths or paused reflections.

His life is lengthened as a stroke over his painting. He maintained a constant communication with the world that inhabited his paintings: with himself and the things he painted, with himself and the people whom he painted from Clotilde, his wife, to his sons and his models. He painted what he liked, especially the sea and its surroundings. Everything had to be cheerful, cool, loud, flooded with light. He painted everything with strength and vigor. He was a temperamental and emotional man and could not engage in something that did not attract him overwhelmingly. In cases where he should engage in a portrait commissioned corseted, the quality of his work was suffering. He moved away from all that gave him coldness. The sobriety of Castilla would frighten him. When painting Castilla he said: "I painted all day and I'm not happy with the work (...) I do not know what happened here (...) but it attracts severity (...) I am less encouraged to continue in Avila, the Castilian bothers me, it is too barbaric. "

And yet he was excited with Andalusia, with the partying and the bulls ...

Analyzing this position –vitality against intellectuality- we discover how art moved and fascinated him. And so we see how Sorolla never showed any interest in taverns; he stayed away from any art analysis as cubist art was, that developed alongside him. Between 1907 and 1914, Braque, Picasso and Gris convert still life into one of their favourite genres: they planned to reduce nature to simple geometric shapes. Nothing too far off from the paintings of Sorolla.

Sorolla: Under the awning,1910.

The fundamental characteristic of his work is the search for the natural. It is true that in his paintings one can see traces of Naturalism, Impressionism, even Fauvism, but always in his way.

He shared many traits with Impressionism: the plenairismo, a clear palette, the tendency to sketch, the weakening of the issue in favor of the environment ... However, unlike his Impressionist colleagues, he did not come close to science in search of the decomposition of light and colour properties. That intellectual search Sorolla disliked and was devoted entirely to the pure emotion and what he saw as natural. "What for? If the normal eye sees colour together why, then separate it?".

"I AM HUNGRY TO PAINT(...) I SWALLOW, I OVERFLOW, IT IS CRAZINESS"

(Sorolla)

This exhibition also shows an overwhelming quality of Sorolla: the indefatigable worker, lucky beast unable to stop.

They are great rooms, also dark, small, crowded, certainly turned into Studioli or jewellery cabinets, in which the viewer enjoys the notes made by Sorolla, either on their small oil boards with landscapes and sketches, along with his drawings from the US hotels or the back of menus of Parisian restaurants.

Sorolla: Coffee Scene, 1911.

"When do I paint? Always. I'm painting now, I look at it as I talk to you".

Sorolla made more than two thousand small paintings throughout his life. They did not exceed 20 or 30 centimetres. The so-called "notes" or "color spots ". And he painted them for himself, for pleasure, like sketches or essays that conveys the artist's soul. They were a scanner of how the painter looked or felt. His most intimate and free side.

They were the immediacy of the look: one that looks and paints at the same time. Hunger of the painter for letting his hand, like a writer extends its pulsations in an outline of what he is seeing or feeling: out of necessity to vomit what explodes within him.

That uncontrollable lava which Sorolla advanced in his studies of nature, capturing snapshots, light changes, no matter if it were a piece of a wall and his limed white, the reflection of a tree in the water of a pond, the arms of children reduced to tiny strokes, alternating with touches of the spatula, to capture their jumps in the waves ... This custom of the notes, to paint for himself and the small format was already known from Goya and developed by painters who took their paints outdoors, whether it be Fortuny or Pinazo, Sargent or Boudin. It seemed that Fortuny had invented an ingenious box of notes that facilitated the convenience of outdoor studies. It was a box with two parts connected by hinges: the bottom to act as a palette and where colour tubes and brushes were kept; at the top, was the small board in a manner that when standing, could receive the painter´s creation.

These notes become especially interesting in the end, when freedom and the security itself is already full. They become evidence of the advancement of the technique and the search for light, while the shadows are forced to the limit and painting sharpens its modernity to remind us that Sorolla works at the time of the photography and passion for Japanese stamps.

"Now is when my hand listens completely to my retina and my feeling. Twenty years later!" said the painter at the end of his life.

{youtube}okIP00Hoc3E|600|450{/youtube}

- Details

- Written by Marta Gnyp

Indian superstar artist Subodh Gupta draws inspiration from Hindu mythology and Bollywood. His own life could also inspire a movie: a young boy from a large family growing up in one of India’s poorest regions, discovers a talent for drawing. He attends art school, moves to Delhi, works in theater productions and visual arts. He develops a hyper-realistic painting style where kitchen utensils serve as subjects, then goes on to create large installations and sculptures. Within a couple of years, he becomes an internationally acclaimed artist whose works are sought by famous collectors worldwide. Marta Gnyp: The prophecies about our world as a global village seem to have come true. Thanks to new media, the Internet and the fast-pace of communication, we all seem to speak a similar language— even in the field of arts. Do you consider yourself an artist who works in the tradition of Western art? Is it inevitable that a good international artist has to relate to the Western art tradition?

Author: Marta Gnyp

Indian superstar artist Subodh Gupta draws inspiration from Hindu mythology and Bollywood. His own life could also inspire a movie: a young boy from a large family growing up in one of India’s poorest regions, discovers a talent for drawing. He attends art school, moves to Delhi, works in theater productions and visual arts. He develops a hyper-realistic painting style where kitchen utensils serve as subjects, then goes on to create large installations and sculptures. Within a couple of years, he becomes an internationally acclaimed artist whose works are sought by famous collectors worldwide.

Cocoon, 2009 brass and metal alloy, ø 183 cm courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich, © Subodh Gupta

Marta Gnyp: The prophecies about our world as a global village seem to have come true. Thanks to new media, the Internet and the fast-pace of communication, we all seem to speak a similar language— even in the field of arts. Do you consider yourself an artist who works in the tradition of Western art? Is it inevitable that a good international artist has to relate to the Western art tradition?

Subodh Gupta: No. For me art has one language and it is not relevant to divide the artistic legacy and production into Western or non-Western. We all work in a similar way, from the visual and conceptual point of view. The art language is, however, not a common thing; it is something very secret and private. A good complicated movie or a good book can be understood easily by the attentive reader who knows how to read and interpret it. On the other hand, the artist is always rooted in his own tradition. This is the reason I use Indian objects and Hindu rituals. Jasper Johns could make the American flag the way in which he did it only because he was an American artist; it would carry a completely different meaning if a Chinese were to make it.

Incubate, 2010, 25 stainless steel eggs, 5 chandeliers, variable dimensions installation view Subodh Gupta.Take off your shoes and wash your hands, Tramway, Glasgow, Scotland, 2010, © Subodh Gupta courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo: Alan Dimmick

MG: I read that getting to know the works of Marcel Duchamp was very important to you: you even recently remade one of his readymades which referred to L.H.O.O.Q., his Mona Lisa with a goatee Et tu, Duchamp? Do you consider the daily objects you use as a form of readymade? According to Duchamp, the readymade has to fulfill two criteria: it has to be visually neutral and not personal. I wonder whether these criteria apply to your work —firstly, because they are visually very attractive and secondly, because as I understand, they appeal to many Indians by calling up childhood memories. What is the function of these objects for you?

SG: I don’t believe that the ready-mades by Duchamp were not visually attractive to him. I respect Duchamp as a great artist and thinker and the Mona Lisa was a kind of homage to him, an expression of my admiration for his great artistic freedom in thinking. But my objects have a different character; I don’t care about the ready-made concept of Duchamp. I use what interests me, what is mine, what fits into my way of thinking and art making. Those simple kitchen utensils are a visual paradox of the shiny attractive appearance on the surface and the emptiness inside; they show in a very accessible way the extremities of our time: the nothingness and the exuberance, and on a concrete level, the lack of the most essential ingredient of our life—food and the striking accumulation of hollow expressions of any kind.

MG: Does this partly explain why your work is so successful outside India as well?

SG: My themes are universal, although my references could be named the Indian village traditions, i.e. usage of cow dung and the importance of food. There is a combination of local and global languages. Everybody can read and understand in my art the paradoxes of our life.

Terminal, 2010 brass, thread, variable dimensions installation view Subodh Gupta. Take off your shoes and wash your hands,Tramway, Glasgow, Scotland, 2010, © Subodh Gupta courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo: Alan Dimmick

MG: Have you been surprised with the enormous success of your works?

SG: Well, actually not. I am not surprised who I am.

MG: At what moment did you first feel you were an artist?

SG: I have always felt I’m an artist, even from the very beginning when I started to draw and paint but didn’t know what art really meant. I didn’t know what was good and what was bad art. I have been experiencing this fantastic energy ever since, and I have always been a very self-confident person about what I’m doing. I like it when the challenge becomes bigger every time for me as an artist.

MG: What is the status of the artist in your country?

SG: I spend the days mostly in my studio; I’m not a person who goes out very often. The artist is, in my opinion, a very normal person. The magic which is needed for my work can be found everywhere within the normal life of my friends, my studio, my surroundings, in common life.

Two Cows, 2003 – 2008, two bicycles, bronze and chrome, 42 × 73 × 18 cm © Subodh Gupta, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich

MG: Speaking of your friends, the works of your generation of artists in India are so strong and omnipresent that one speaks about the Indian Renaissance. Why is it happening now? Is there an urge to express a new Indian identity through art, related to the country’s more powerful economic position in the world?

SG: No, I don’t believe in this statement. Artists from all generations have been important; I respect very much the modernists, to give you an example. Of course, the contemporary life—not only in India—is very complex. People have the desire to see more and want to be confronted with the new in a very fast way. I can sense two opposite dynamic powers in our time: one wants to bring us closer to each other and the one wants to divide us. Art has the power to bring us together. Seeing the recent developments from this perspective, art all over the world is becoming reshuffled; it is not only the Indian renaissance but the general increase of interest in arts. Look at the number of galleries, collectors and museums abroad. To the contrary, in India, we don’t have one single museum of contemporary art. Surprisingly enough, people abroad have other ideas about contemporary art in India. The fact is that in this huge country, we don’t have places to show today’s art. We have a long way to go.

MG: It means that the position of the collector in your country is very important because they have the task of supporting the artist and making the art possible.

SG: We don’t have a lot of collectors in India. We cannot always count on the few collectors spread out all over the country; foreign collectors who love our art are more important. Most of the people in India who love contemporary art have no money to spend it on art. On the other side, the richest people operating in the global context have often no single artwork in their home, which is sad. Thank god art lovers from abroad give us the possibility to express ourselves and to grow.

Still Life, 2009, marble, wood table, 120 × 213.4 × 76.2 cm, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich, © Subodh Gupta

MG: Your works are being sold mostly to foreign collectors?

SG: Yes, sporadically to the Indian collectors, but mostly abroad.

MG: Speaking of buying and selling art, did earning huge amounts of money somehow influence your life?

SG: No, where I’m coming from and who I am doesn’t matter; principally, the artist has the right to live a good life. If we are lucky to succeed in our life, why not enjoy it?

MG: Do you see a connection between your art and design and fashion? Do you see this crossing of disciplines as something typical for our time? If yes, does it bother you?

SG: Not at all. I love fashion and I love design. Merging of disciplines can be very fruitful. Look at what was happening during the Venice Biennale 2005, where architects, photographers, filmmakers, video artists, painters, and sculptors met in one platform. Fashion and design are very close to arts; they are definitely linked to each other. I respect them all.

Untitled, 2010, oil on canvas, 167.6 × 228.3 × 4 cm © Subodh Gupta, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich

MG: Your wife Bharti Kher is also a successful artist. Both of your personal stories sound like a dreamy Bollywood movie: a British young artist of Indian origin traveling to India for the first time meets an Indian artist and falls in love—without even speaking a common language. Then she moves to India and now, you work and live together. Did you start to look differently at Indian culture through her eyes?

SG: Yes, we became very close and as a foreigner, she wanted to understand how the system works so she asked me many questions. However, you cannot change the way you see, you can only start thinking differently. You are who you are; you cannot change rituals, not in your country, not in any other place. But you can change your own thinking—only you yourself, nobody else can do it for you. If I’m looking bad, that’s me who is looking bad. If I’m looking good, that’s me who is looking good. The perspective of every individual changes over time, but your destiny does not. So my language definitely changed, but my heart didn’t.

MG: Do you see your art changing in the near future?

SG: I always experiment. My theater background helps me to look from different angles. I am not planning anything beforehand, but you will see after a while that my art looks different.

Et tu, Duchamp?, 2009, black bronze, 114 × 88 × 59 cm, installation view Subodh Gupta. Common Man, Hauser & Wirth London, 2009, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo: Mike Bruce, © Subodh Gupta

MG: What connect all your works together? What is for you the essence of your art?

SG: For me, art is about time. Art has the power to express feelings and ideas; it makes us understand what was not understandable. Duchamp is able to make us look and see differently: how much we owe the person of Duchamp, and how much to his work, we don’t know. Yet, the visual language is so powerful and so individual that without looking at the works of Duchamp, I couldn’t look into Duchamp as a person. So for me, as an artist, my artwork is me, but without my artwork, I am nobody.

MG: What would be your dream project?

SG: I don’t know. I’m dreaming all the time.

Subodh Gupta is represented by Hauser & Wirth in Zurich, London and New York.

- Interview with Subodh Gupta - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

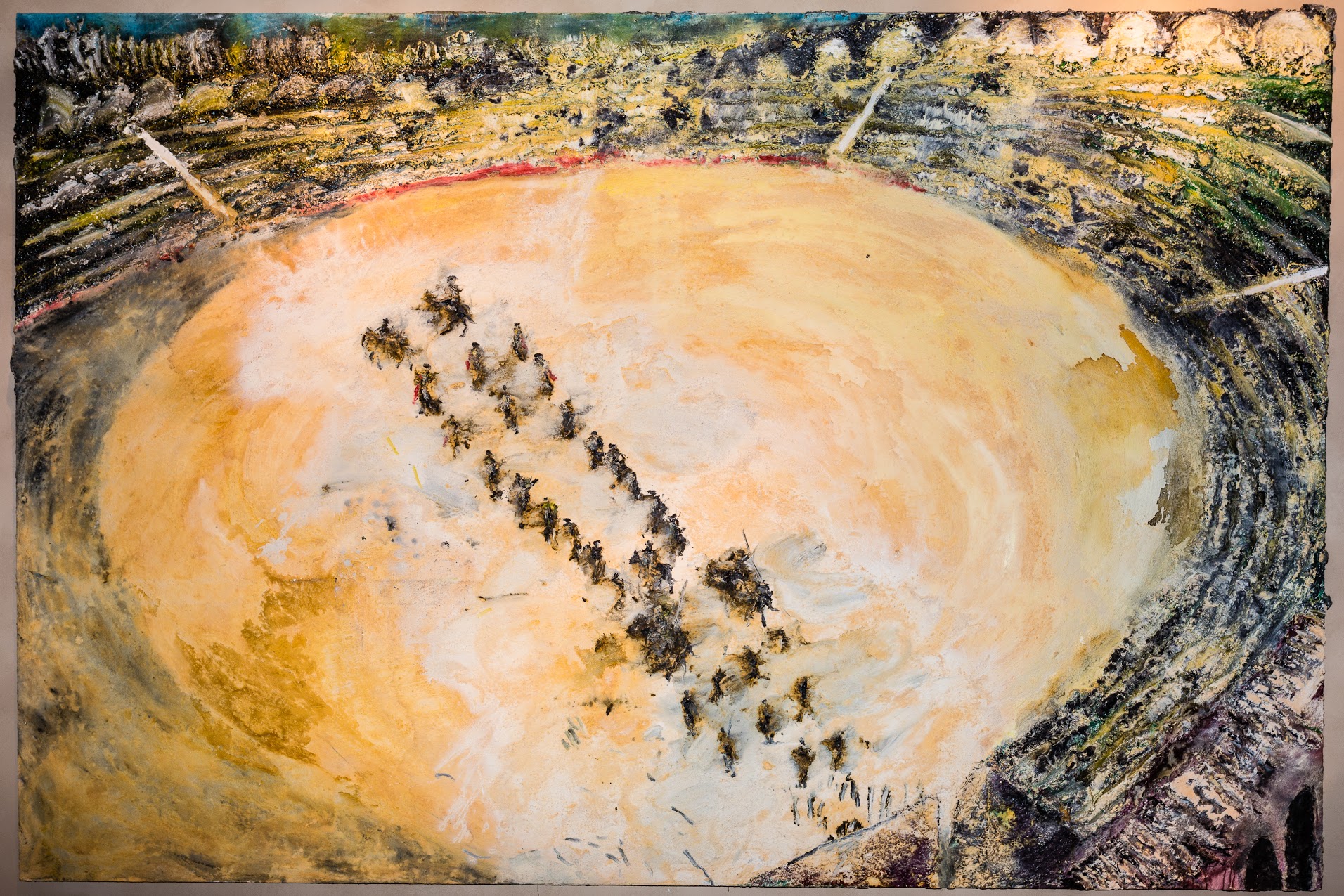

The career of Guillermo Kuitca (Buenos Aires, 1961) began at nine-years-old when he entered the workshop Ahuva Szliowicz supported by his mother, Mary Kuitca, a psychoanalyst, but especially by his father, an accountant named Jaime Kuitca. From here, he left at 18-years-old, having turned into a precocious painter; he had his first solo exhibition at the age of 13 and taught painting classes. His interest in film, music, literature and architecture is present in his work. More importantly, his passion in theatre is present. He is the author, director and set designer. His work is included in the collections of major museums including the Metropolitan Museum, MoMA, Tate Gallery ... But the most interesting thing about Kuitca is that, thanks to him, future generations of Argentine artists have formed.

Author: Elena Cué

The career of Guillermo Kuitca (Buenos Aires, 1961) began at nine-years-old when he entered the workshop Ahuva Szliowicz supported by his mother, Mary Kuitca, a psychoanalyst, but especially by his father, an accountant named Jaime Kuitca. From here, he left at 18-years-old, having turned into a precocious painter; he had his first solo exhibition at the age of 13 and taught painting classes. His interest in film, music, literature and architecture is present in his work. More importantly, his passion in theatre is present. He is the author, director and set designer. His work is included in the collections of major museums including the Metropolitan Museum, MoMA, Tate Gallery ... But the most interesting thing about Kuitca is that, thanks to him, future generations of Argentine artists have formed. In 1991 Kuitca created scholarships where they study and work in disciplines related to the visual arts.

Elena Cué: With a precocity like yours, what memories remain and who has made the greatest impression on you?

Guillermo Kuitca: Undoubtedly, the figure of my father has been very important in this case. He was very excited when I became an artist. His interventions were very subtle, but I remember when I went to buy the first fabrics, the first easel and first brushes, I always went with him, and I imagine it left a notable mark on me. Many years later when I was already a painter totally dedicated to this and absolutely committed, Dad told me that in his youth he had tried to paint. He was from a humble family, which meant having to steal the hairs from his father's shaving brush as well as cooking oil; luckily things I learned much later, because children are very sensitive to every little thing.

E.C: His pictorial series have changed according to their own rhythm, but also the historical situations; this applies to "Nobody forgets anything" (1982) in pure conflict with the Falkland's war. For this series he locks himself in his studio using whatever material is at hand: doors, wood or fabric. It is a very intimate series but also a political and historical view of the world; depicting the bed as the central image, women and heartbreaking scenes over and over again. The bed is a symbol that has accompanied him in his work as the installation Untitled, 1992, using 52 mattresses painted with maps.

Why the eternal recurrence of this object in your work? Has your concept changed over time?

G.K: I saw the bed as a vehicle that I could use to move through human experience and through my work, as if the bed had wings or wheels, that is to say, the image has neither one nor the other, it is rectangular with legs but has the potential to move through time and space.

There is something very basic in the image that exists as a kind of heart in the works and I think that persists until, I think, 2013 with a big play called "Double Eclipse". This had a number of beds and it is as if there was something from that first experience, from that bed in 1981-1982 that is maintained. Of course my views on this subject are changing, extracting excessive forms of conceptual links: psychological, political, or sentimental things. How to turn the bed into a rectangle as if it were a plan of where life happens instead of the demarcation of a house, of human experience, like taking it to the most essential point possible. But that concept I would say almost survives along those in which is the human experience, birth, death, sex, sleep, illness, reading ... this stunning cluster of intimacies that occur. From the most sublime to the most banal. So I would say that more than the evolution of the concept, it was like taking adhesions that had stuck through time. The bed as pictorial representation is almost like a perfect equation that produces a very simple representation as an absolute inclusion, taking advantage of the huge space.

E.C: Psychoanalysis has been present in his life from an early age. His mother and a childhood influenced by therapy sessions have contributed to this, which meetings he went to reluctantly. If the origin of art lies within the subconscious, hidden deep in our personality, this reality finds a way to manifest symbolically, says Freud, through dreams; also by spontaneous writing or scribbles where aesthetics and morals of our consciousness are not involved. Both are used in his works. His "Diaries" series are paintings made on canvas where he scribbles, draws, notes and paints over months of his daily life. These involuntary diaries and oniric aesthetics in many of his works, where the figures live in half-empty spaces with disproportionate scale, surreal disjointed scenes, leave an unsettling impression.

The most intimate, the product of pure thought, emerges in your paintings. Does painting facilitate knowing oneself? How do you feel about displaying these in public?

G.K: Interesting paradox ... because while I like your version, for me, and I guess that for many artists it does not rule out a process of self-knowledge. Without doubt, there is an inner expression brought into play and that is how it becomes accessible. It is also true that for me, the power of the artwork exists in the privacy that is created between the work and the viewer. Therefore, the work is not what is between the viewer and myself, that is, the access to me personally. But I think the strongest aesthetic experience is the relationship created between the work and who looks upon it; therefore I tend to disappear from the scene. I think that trying to look at the work while wondering about the artist, what is its truth, what is its secret etc., is probably losing the richest artistic experience, in generating a particular privacy. That, in general, the painting produces this kind of miracle, which is what I see, what happens to me. Sometimes nothing happens, it's almost like an experience of love; like a secret between the work and I, the individual looking.

Of course it is entirely lawful and I accept all kinds of visions and do not think some are more legitimate than others. However, I believe it is richer to ask oneself whether the artist who made this work is hidden, or vice versa, whether they are revealed in these details. On the other hand, everything is automatic work, for example, on the tables in my Diaries, rather than subconscious. It is automatic work, it is a kind of restless hand which marks things. It is not a test. In that sense, I like it when you think of the environment as rarefied as they are in dreams. But it is also true that there are many more dreams than dream interpretations, and Freudian psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic techniques in something that is already more than 100 years old. This is not to do with the dream, but interpreting the dream. In that sense, one can dream without interpretation and I think the public who visit visual arts, the trained and untrained, either from exhaustion or disinterest, even including the fortunate, have abandoned the permanent temptation to try and interpret the artist or the work.

I think there are thousands of possible entries to a work and perhaps only one of them is interpretation. In my case, I was born in a family where psychoanalysis was very conventional, it was not uncommon. In a city where many people were analyzed, psychoanalysis did not appear as something exceptional; I only saw it as a peculiarity with pros and cons. As you say, I could have been analyzed myself, I was in a situation where the guys here in Buenos Aires in the modernity of the 60s, were sent to the analyst when they sneezed instead of going to the doctor to take an aspirin, everything was considered to be psychosomatic, there was a kind of total abuse of therapy. And no guy liked to have their head messed with. Sometimes, with the access that the public have, the critics are surprising because it is believed that the work conceals oneself and actually substitutes in a way that if you were aware of it, you could probably not do it.

E.C: His work has developed over time with varying central motifs: the first works with distorted figures, quilted beds covered with maps, architectural and city plans, newspapers, maps, the empty luggage carousels at the airport, unclaimed suitcases as representations of the orphan, are examples of what have interested him at various moments.

What is the relationship between the choice of your motifs and your obsessions? Up to what point is art a channel for them?

G.K: I think there should be a very direct line, of course, the work itself is already very obsessive but probably thinking about it is decoded at that time. I sometimes look at my works from the past, and I understand what was in my head at the time of making it. At the time of doing it, I didn't necessarily consider my obsessions, because the process itself is very demanding and absorbing and it is perhaps all that is needed to make a work. I am in dialogue with the painting, in a kind of battle and sometimes this bypasses a reflection of where my head actually is. Anyway, at the time, I am also looking at what connects all of these, and what themes are being projected. When you mentioned all the topics that have been present in my work, there is a huge body of work that has the theatre existing between these sequences of beds, cities, the maps and after, the leap to the luggage carousel. The theatre was a very important issue; somehow I had to make it rotate from the view of the stage to the view of the audience, as a permanent exchange. When the first luggage carousel appeared, it appeared as a backdrop, like a stage platform, almost as if it had nothing to do with with the representation. Of course I was interested in the unclaimed luggage, desolation, but the first luggage carousel was a response to the stage area. Then, as the works acted as signposts, the best one can do is not to resist but to continue on that path.

E.C: So it is only possible to notice these obsessions in retrospect...

G.K: The work is more intuitive. I don't know if I'm a good observer of my work. Of course, I investigate and submit my work to all types of analysis; the cruelest possible. But when I do that, there is an intuitive element that I do not want to lose. If I constantly ask myself what I am going to do then I lose the purity, arbitrariness, intuition and nonsense that are very important moments, in which the work opens up to the other, the viewer. If not, it is always a self-reflection. For me it is essential to concentrate and not to ignore what the work asks me.

E.C: What is art to you? Do you think art should also have a utilitarian purpose that is intrinsic to our time? Or is it closer to what Schopenhauer said, when describing art as a drug that temporarily eases the suffering produced by our continuous chain of needs and desires, against our will?

G.K: Obviously Schopenhauer's time is not ours, but if art were a drug or balm, as Derrida said the drug is both a cure and a poison, that will become his own utility. In this fragmented world, art in its most sublime expression does not produce experiences that can soothe or solve all our frustrations. In this sense, I do not think that it is ever one hundred percent effective for the human soul, and I do not think that utility is the barrier that makes this impossible.