- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

Joana Vasconcelos: "Artists manage to open a new path to beauty". The Portuguese creator conquered Moscow, Venice, Versailles ... where 1,600,000 people visited her exhibition.

In Lisbon, on the banks of the Tagus, is the studio where the artist Joana Vasconcelos (Paris, 1971) deploys all of her creativity. With her I made a tour through the technology rooms, the foundry, architecture and sewing rooms of the world of this Portuguese artist who conquered Versailles.

Elena Cué: Her birth in Paris was a result of the asylum her parents asked for in France when they escaped from the Salazar dictatorship. What configured the presence and affirmation of her roots and identity in her work?

Joana Vasconcelos: The fact that I am a Portuguese artist today is the political outcome of the dictatorship that conditioned many people in Portugal and Spain. My parents were in France and I was born there and the truth is that their life would have remained in France if there had not been the Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos). I think they would have stayed there and today I would be a French artist. Internet allows the artist to live in their country and to export their work without problems. People reflect their identity, but not only where they come from but also where they are; in other words, the artists can exist in their countries. This allows a person like me, a Portuguese woman, to be in Portugal. It's like another view of art.

What can you tell me about your childhood that has been important in your work?

My childhood was very normal, like all children. What I did that was different was karate for many years. It taught me to be very demanding, to achieve a level of results; it has to do with doing one thing from beginning to end. High competition workouts are very demanding. If we apply this to art, I would say that when I face a challenge or an order, I feel as if I were in a championship, I have to train to get a result. I could have made a career in karate, but there was a time when I wanted to go to art school, and I did both activities together. But after a week in Arco, I went for training session and broke my knee. That was when I understood that I could not continue in karate but that I could use all this training as an artist.

You are an artist committed to human rights and, in particular, the role of women in our society. What do you want to convey with your work, what dialogue are you seeking?

It depends on the work. I'm an artist, we do not think like men. I can be talking about the rights of women but also about beauty, the East, and the piece I did for Macao. It is another concept that has nothing to do with political things, it has to do more with the idea of beauty, volume ... I can be talking about communication. Women are like that, they can do many things at the same time, men can not. Men have a more linear discourse, it is another way of thinking, neither better nor worse, just different. We are like that. It is no longer necessary to have a single discourse.

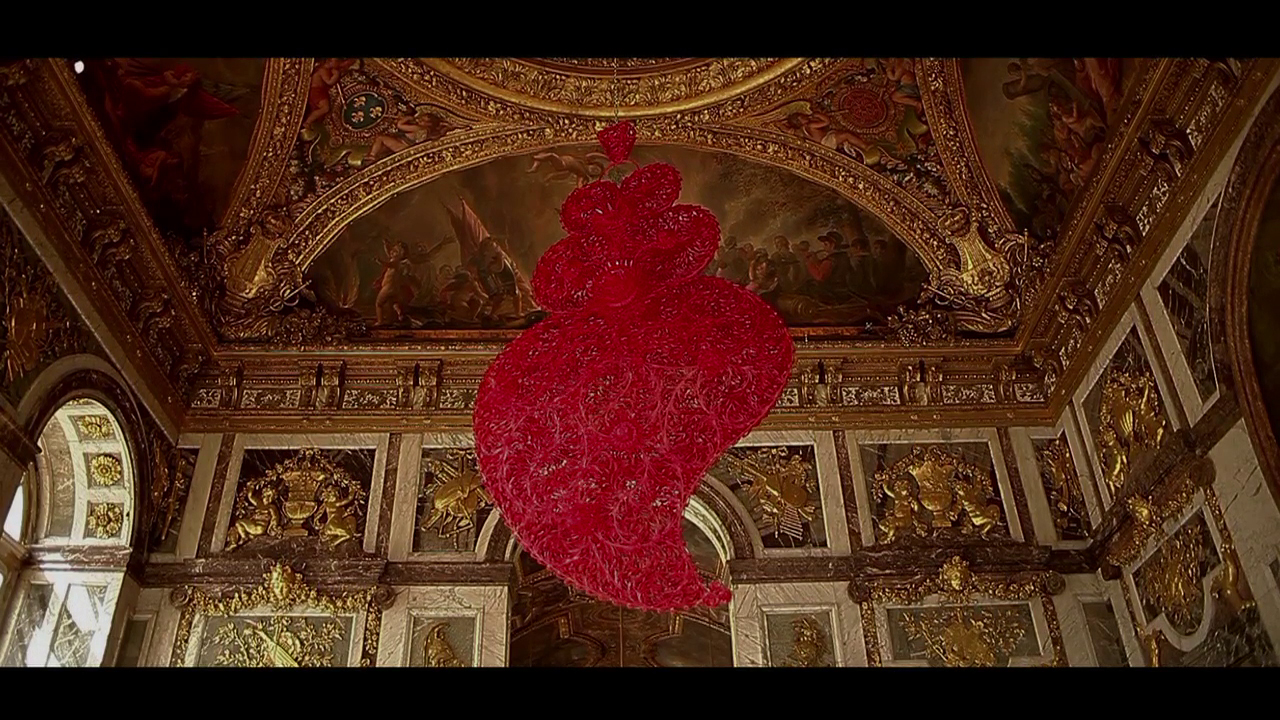

What has it meant for you to display in Versailles?

I can not answer without telling you two or three things. I am the result of a time, of identities, of a change in the way we look at the world. Versailles could not have happened without first doing the Venice Biennale in 2005 with Rosa Martinez and Maria Corral, because they were in fact the first women at the Venice Biennale and both Spanish. I was the first woman in the Rosa Martinez exhibition and the world realized that I existed as an artist and I am very grateful. I was with Maria Corral in Venice and we said that there are people who are at historic moments and do not realise. This was my case in 2005. Then I did more things that led me to Versailles. In 2005 the world realized I existed but I had no works. Then I did a couple of exhibitions. One of them, in the Garage in Moscow, which was the first group contemporary art exhibition, and I was part of it. It was also a very important moment. Then I did another in the Palazzo Grassi in Venice and was there in front of all the big names: Struth, Jeff Koons, Murakami ... And again I had the chance, much younger and female, to be amidst a group of awesome people. Then I was invited to give an exhibition in Versailles. It would never have been possible if I had not done these international exhibitions where your work is alongside all these great artists of the world, where you have a presence.

You engage in a dialogue between past and present. When do you think that the great change in art takes place?

You were asking me what Versailles meant for me. Versailles changed everything. The exhibition had 1,600,000 visitors. Why? First, I am Portuguese. Second, I do not have a large gallery. Third, I have no great curator behind me. Fourth, no one knows me. 1,600,000 visitors! Jeff Koons had 850,000, Murakami roughly the same and you wonder, why? The truth is that the impact is greater for a woman, and I am also European.

You are closer to our culture ...

It's a culture that I understand, that we share in Europe. I integrated my work, I didn’t confront it with the palace. There was a divine union between the work and the space.

The great beauty of Versailles. Where does beauty lie in art for you?

For me art has to be beautiful. I believe that beauty and art are synonymous. I do not think it resides, I believe it is.

That moment when subject and object are the same ...

Yes. I think very much about the time, the emotion, the intensity ... I believe very much in the truth, in the idea that there are no lies, that communication is direct and sincere. If you look at these pieces they are not hidden, they are not isolated from the visitor, they are here present. And then you have many laws of understanding, you can look for this or that, but the truth is that they are hidden behind a theory. Then you can generate your own, but you do not need theory to exist. Beauty does not need theory, beauty is.

The big question, what is the concept of art for Joana Vasconcelos?

I think that art is what we are describing. It is the ability to generate a dimension of beauty and new light, that is, to me it is more interesting to talk about works than artists because those who are artists are the ones who manage, through one or many works, it depends, to open a new way for beauty, for understanding the world and to have a new perspective on the world. Art is the need to represent ourselves in complete freedom, art is the ability to keep the world alive, to keep our construction as human beings alive. This is why 1,600,000 people visited my exhibition because I represented Europe in a natural way. And when you are in a crisis it is more important that the artist should be in your country and represent your culture because otherwise, as in the Palaeolithic, you do not know what happened to the tribe that did not do the drawing, you know about the one that did. I not only represent my country but also this idea of common culture that we create in Europe.

I remember our first meeting in Venice. The connection between Lisbon and Venice through a ferry turned into a work of art after being covered by its wool, fabrics and crochet and the famous Portuguese tiles was an amazing experience.

Yes, the boat was the most complex and difficult project I had ever done. It took us a year. We did not have much budget either and the truth is that my country helped me, companies and individuals sent me money and it ended up being a movement of support to get me to Venice. It is at times of crisis when people want to have a say, when they want to be represented and not lose their identity. It was a national project. I had to reflect what Lisbon is today, which elements are specific to our identity, like the tiles, what we have in common with Venice, like the boats, the river, the fact that we are two tourist cities, the fact that in the 15th century we were strongly connected. There is a historical connection but also a contemporary one. For me, the connection was the water, for Lisbon and Venice water has complete control over the city. Then I took the boat and we transformed it. It was an amazing life experience. It is possible to do everything you think. It was sincere because people realize and help you. We must continue representing ourselves in the world. I came to Venice because the Portuguese wanted to come and I'm very grateful. It was all tough, the transport, the opening ... but we managed.

- Interview with Joana Vasconcelos by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Architect Jean Nouvel Invites Us into His Creative Thought Process and Discusses His Current Battle over the Paris Philharmonic. >The Paris studio of architect, Jean Nouvel (b. 1945, Fumel, France), serves as the meeting place for our interview. Nouvel is one of the key members of an exclusive group of architects, which has been honored with the most significant architecture awards in the world, including The Imperial Prize of Japan, The RIBA Royal Gold Medal, The Pritzker Prize, The Aga Khan Award, and The Wolf Foundation Arts Prize.

Architect Jean Nouvel Invites Us into His Creative Thought Process and Discusses His Current Battle over the Paris Philharmonic

The Paris studio of architect, Jean Nouvel (b. 1945, Fumel, France), serves as the meeting place for our interview. Nouvel is one of the key members of an exclusive group of architects, which has been honored with the most significant architecture awards in the world, including The Imperial Prize of Japan, The RIBA Royal Gold Medal, The Pritzker Prize, The Aga Khan Award, and The Wolf Foundation Arts Prize.

Elena Cué: The anti-Le Corbusier architect Claude Parent was your mentor when you were starting out at the age of 21. Please tell me about what meeting him meant for your career.

You were actively involved in May 68 with a radical stance against the educational model of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. What were the things you demanded?

Jean Nouvel: I felt that his studio was one of the most creative at that time. He and his partner, Paul Virilio, created a space where a new approach to architecture could evolve. Paul became a very well-known philosopher and thinker of the time. I joined the intellectual rebellion of "May 68" and it certainly impacted my architectural style in terms of its criticism of the way in which French cities have traditionally been constructed. Later on, I joined with them to create the "March 1976 Movement," which demanded that the design of French cities no longer follow the same traditional model. Soon after, the architecture trade union was formed. It was a time of intellectual excitement.

EC: How would you define your architectural thought?

JN: I think it's similar to the solidification of a cultural experience, which means that ultimately, every generation has a job to do. Cities are made from an assortment of constructed testimonies, which reflect the things that each generation specifically liked, the different techniques that were used at that time, and their relationship with art. I've spent my life fighting against certain forms of academicism. It's true that there's an actual entity that's devoted to reproducing models from the past—the worst things from the worst situations and then making them pastiche. A pastiche, in reality, is always a degradation of what was true at an earlier time. It's like a ghost or a faint remnant of the past. I believe that every place deserves careful consideration.

In my opinion, every project is the start of an adventure, and clearly, I never seem to know where I'm going. I don't start with a preconceived idea. I always begin with a hope that the place, the experience, and the people with whom I am going to find myself at that moment are all going to contribute something completely unique. This sort of precision and nonconformity serve as an attack on the concept of cloning. Along these lines, there is something that has made the situation even worse—the development of information technology. Nowadays, the guidelines for creating any kind of project are readily available. As a result, you can design a building in a few hours based upon these predetermined criteria. It doesn't matter if they're residences, offices, or shopping malls. You select from what already exists, adjust a few elements, and just like that, it's done. Unfortunately, there isn't any gray area. There isn't enough thought, planning, or love in the designs that come about like that. They're automated and don't have any soul.

EC: In your work, as you say, you try to create a space that would be the mental extension of what is seen, a space of seduction, veiling and unveiling, looking and going unseen, concealing, light and shadow, mystery. How much is there of the erotic in your work?

JN: When there isn't mystery, there isn't seduction. Architecture is a mystery that must be preserved. If everything is revealed at once, nothing will ever happen organically. Without a doubt, concealing is one of the elements of eroticism and therefore, of erotic architecture. So, if we look at the Cartier Foundation, for example, you have two parallel, clear glass panels on a surface creating a mysterious uncertainty because of the way it plays with the reflections of the trees and the clouds.

There are also situations where you can play with the presence of nature to the point that you wonder if it's really a garden, for example. A garden is where thousands of natural species have reproduced and are coexisting together. All of these things, as well as the interference with the sun and the rain, create certain sensations that we aren't used to feeling. It's a form of simplicity that truly hides an enormous complexity and this complexity is what distinguishes that specific location. The reflections and the porosity of the emerald-colored glass make it so that you can hardly see what's behind. When you put blinds on the inside, it appears as if the landscape is printed on them.

Essentially, one attempts to choose ways of concealing, ways of showing, ways of hiding, ways of saying things or not saying things, and ways of suggesting things, but not ever formulating them. That is architectural eroticism.

EC: You work is highly heterogeneous, your buildings adapt to the space, context and culture with which they will coexist. For each project, in what factors do you seek your inspiration?

JN: In life and situations. I believe in situational architecture. Circumstances don't only relate to the actual place, but also to the aspects of an encounter or an appearance. In this regard, I'm considered a "situationist," but I don't think you can design a building just like that. A building isn't a sculpture and it typically doesn't change places. Some are relocated, but that's very rare and I feel like those situations are completely unpredictable. For that reason, we are always searching for anything that can impact a project and change it, which means that we must respond to lots of questions and concerns. You have to realize that architects are always considered to be incompetent and yet their work in and of itself must be highly competent. Every time I'm asked a question, I have to view it as if I'm coming from the opposite perspective and there are a lot of things I just don't know. For that reason, we are obligated to listen, to take into account, and to understand all aspects of the question at hand, every single time. Essentially, you must always combine the outside perspective with the inner viewpoint.

EC: So, what is your perspective?

JN: Mine is generally from the outside in. Sometimes it can be from the inside out, but that's rare. I'm always looking for exteriors. Someone that knows a location or a profession very well has inner vision. If you visit a city that you've never seen before, you're able to see things without noticing every single detail. Something quite poetic and pleasing can be emphasized, highlighted, and revisited by those who are on the inside. The architect's first task is what I call catalysis; in other words, it means to put things in their place. When the catalyst is present, things usually materialize with just a tiny spark. Then, there's the job of harmoniously combining all of those elements that, oftentimes, are contradictory. You must try to establish unity or synergy.

EC: The first time I met you, you were disappointed with the end-result of the enlargement of the Museo Reina Sofía. Can you explain what disappointed you?

JN: I wasn't happy. This often happens with me. Sometimes, contracts are not entirely clear and businesses have intentions that are not necessarily the same as ours. It's always been like that, but before, architects had a certain level of power that would get them respect in these kinds of situations. As time passed and the economy advanced, things became much more complicated, like how things are today. Perhaps, at the Reina Sofía, I wasn't happy about some of the conditions that were set forth in stone, but I'm generally not dissatisfied with the profound nature of the project. What bothered me most was that the Council promised to do a bunch of things. There was a study done by Álvaro Siza where the traffic in front of the Reina Sofía would be redirected underground. So, the project was carried out based upon the hypothesis that this would be accomplished. Well, what that means is that the pedestrians are not going to have the same relationship with the building and, further more, there is a sound effect caused by the noise from the street, which bounces off the roof and is heard inside where the original calmness has been lost forever. It's simply not possible to have the same tranquility that was originally envisioned

EC: You have commented that in your building for the Cartier Foundation you mix real and virtual images using glass panes and light to trick the senses. Your aesthetic principles are reminiscent of the artist James Turrel, who explores the perception of space by using light to modify that perception. Are you interested in this artist’s train of thought?

JN: I am really interested in Turrel. He's someone that works with light, nothingness, and location. He's an artist that completely plays with locations. His works simply can't be moved to different places. Their meaning derives entirely from their locations. I'm not talking about the core of the design, which obviously is very close to his vision of the world. I'm referring to the way in which his designs are positioned in order to frame the sky or to capture and create light thereby altering the classification and contours of the location. I really like artists that work according to the situation at hand rather than simply focusing on a few objects that they don't really know where to put. As a result of the commercialized advancement of art, I think that there's a kind of truth to art that is best expressed when the works are done in their original location. They either belong to a place architecturally well or geographically well. Needless to say, all of James Turrel's work involving perspective and light has clearly inspired me for a very long time.

EC: You've designed a lot of buildings in Spain. Which one of them did you enjoy the most?

JN: Because of what I've explained to you, I really don't want to tell you which one. What I can say is that I can't put the Agbar Tower in Madrid. It just wouldn't work. So, for example, people that don't know Barcelona see the Agbar Tower in international magazines and they don't understand it at all. The Agbar Tower is completely Catalonian. It simply can't exist in another location. Its formal design has been utilized by Catalonian architects for many centuries and was inspired by Monserrat's mountainous peaks, which have been shaped by the wind. The phallic nature of Monserrat's peaks is impressive. The fact that the Tower has been designed on an urban scale never seen before and that it's also colored makes it a tribute to Gaudí. The Catalonians and Barcelonians readily acknowledge that the building represents their culture and, at the same time, understand that it was formed from their DNA. On the other hand, the international community only sees the phallic symbol as a suggestion of sexual provocativeness and nothing more.

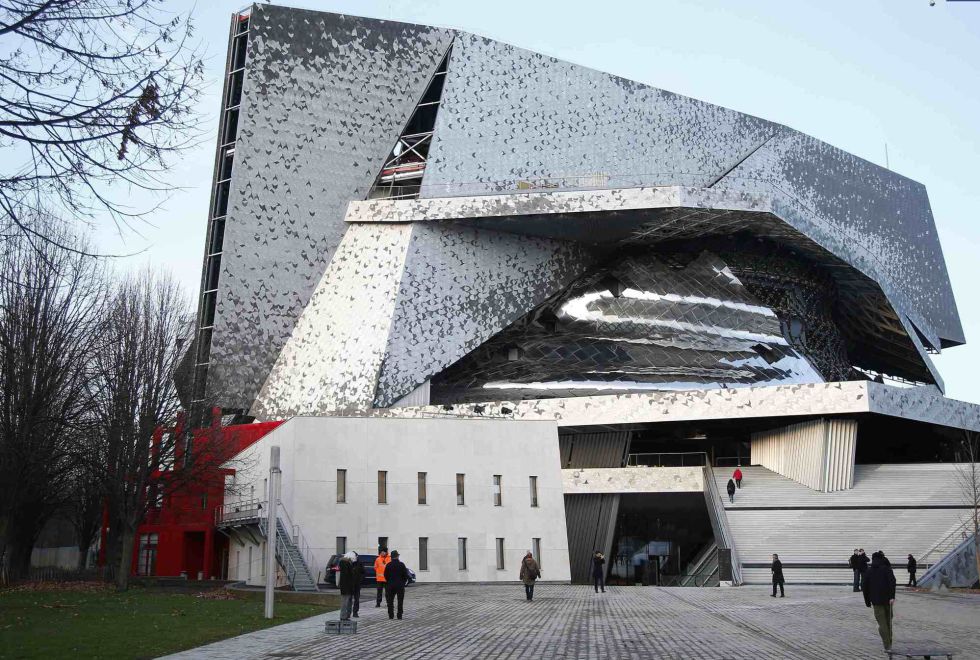

EC: The recently installed Paris Philharmonic opened to the public without your work being finished, and yet it's been an overwhelming success. What can you tell me about this project?

JN: The Philharmonic is a drama and a melodrama. It's the kind of project where normally, everything is in line for success. I feel that it's a project that demonstrates an innovative arrangement of a room on a musical level, a room that successfully defends the use of inside space as well as its emphasis on musical symbolism. Everyone recognizes that. Unfortunately, the building itself isn't finished, obviously. For political and financial reasons, they've done something that's never been done in France since all public buildings are made by a public entity that controls the use of funds. This project was carried out by a private association that decided to hide the rise in cost and, for that reason, they pushed me aside. All of this might seem rather tragic, but in my opinion, it doesn't really feel that way because I'm used to suffering when it comes to my profession. I'm here to defend the pleasure of all music lovers and the artistic aspirations that all of the children will have, thanks to this building. For that reason, I'm going to fight to the end in order to settle this so that the building is completed correctly and no one accuses me of any atrocities about the way in which it was finished, its details, or about the public spaces that surround it. I'm involved in one of the toughest battles of my life.

- Interview with Jean Nouvel by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

"The nerve pathways are something fixed, finished, unchanged.

Everything may die, nothing rebirthed "

Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

Frank O. Gehry in front of a blank page. The terrifying moment of creation. Feeling afraid, waiting for inspiration, stalled by emptiness. Nights of uncertainty. Conceiving an idea: suffering and ecstasy.

We are our brains. The mind is the result of dialogue between each of our hundred billion neurons. How would the impulsive lines of ink appear, led by the right hemisphere of the brain, where Gehry began to dance on paper in one long, winding movement to illuminate what would be the profile of the Guggenheim museum Bilbao?

We think in the head of a genius.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, 1991-1997.

Let us return to the illumination. It is the time when the paper of an artist begins to fill with projectiles: papers flying above the tables with crumpled despair; rough reports of more or less tight balls, containing unfinished sentences, ideas that were lost on the path from the head to the hand; sketches and drawings that do not work.

When Frank Gehry is asked where his imagination comes up from, he rests his pen on the desk, looks up from his glasses, and lets suspense fly in his studio until that gaze drops. Gehry is well aware of his Jewish ancestry, always down to earth, to reality, and says: "Inspiration is in that bin. Look in there, think of the caves, spaces, textures containing that trash". Much of his reflection is there. Writers, painters throw their errors into a basket. Gehry shows his, he wrinkles pieces of paper and transforms them into towers and palaces for music, hospitals made of metal forms that seem to melt under the sun, office buildings embracing dance.

He converts his dream ladder for Vitrainto into the same spiral, the life on a paper. Nothing dies: from the smooth wrapper leaf there is the outcome of a final sketch, to the less valued, relegated to the bottom of a trash can.

Lou Ruvo Clinic, Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America, 2005-2010.

Frank Gehry (Toronto, 1929), winner of the 1989 Pritzker Prize, is probably the world's most wanted living architect. At 85 years old, he has become a total cultural protagonist. In Spain he has received the Prince of Asturias Award. In Paris, as well as the devoted retrospective to him by the Centre Pompidou, he inaugurated the new headquarters of the Louis Vuitton foundation and decorated the windows of their stores.

When in 1997 he completed the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao this architect-inventor-artist, who likes to say that many of the grooves are tribute to Don Quixote, found himself in a similar position to that of Miguel Ángel after his speech in San Pedro of the Vatican: revolutionist of contemporary architecture.

The strength of Gehry - described by the experts - lies in the motion that he embeds within the architecture, in his ability to create that movement from something inert. It is a contemporary cubism that serves to transform a line of twisted metal skin against the sky and glare of the sun, in a factory of feelings and infinite perplexity for its viewers.

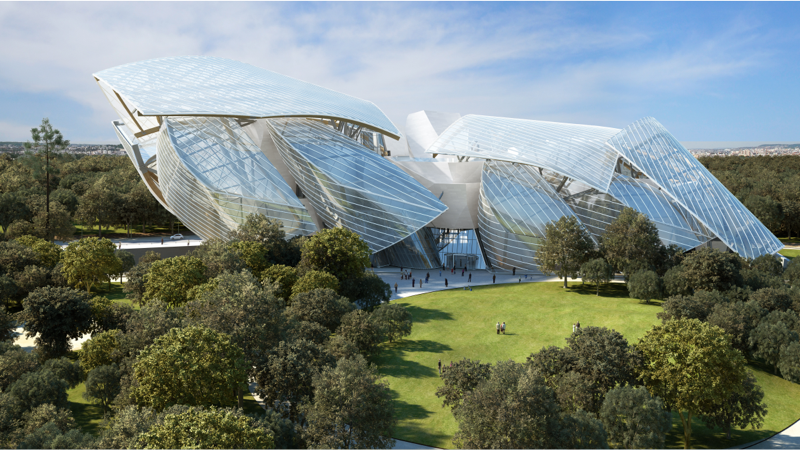

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France, 2005-2014.

Far from feeling that his career as an architect is coming to an end, Gehry recently shocked the world by presenting one of the most complex buildings of his life, another twist of his imagination: that capacity to lead the human eye to sensations, forms and alternative structures. On 27th October he launched his last sailboat: Louis Vuitton Foundation of the Bois de Boulogne, Paris, a developed building designed to promote culture and art, a great museum in which to present collections of permanent contemporary art, temporary exhibitions, entertainment... Bernard Arnault, chairman of Louis Vuitton-Moët-Hennessy, after visiting the Guggenheim in Bilbao, just wanted it to be Frank Gehry to draw his dream.

If Bilbao came from steel, Gehry does not disappoint here in his quest to integrate his buildings in the atmosphere and where they belong. In Bois de Boulogne, the weight of green, the tradition of the nineteenth century greenhouses and configuration of the nearby Jardin d'Acclimatation, 1860, Napoleon III, Gehry approached the pattern of a transparent building. As in Bilbao, there are many similarities: from the igloo to the cloud, to the wings of an insect. "Ultimately, beauty is in the eye" says Gehry, fed up with comparisons between forms and competition between limits of architectural sculpture in their designs.

There are 12 curved glass candles, with wooden gear, inflated by the wind which Gehry, in his passion for sailing, stacks without a hull under the Parisian sky surrounded by ponds and Indian chestnuts and spans the wind which seems willing to go flying over the Parisian mansard so admired by Gehry and whose impact can be followed at the Museum of Art Weisman, in Minneapolis, or the Stata Center, in Boston. "The history of Paris is the history of architecture," says Jean Nouvel.

More than 3,600 glass panels produce that feeling of transparence which integrate the inner and outer, constantly linking water, forest, the inside garden and producing continuous changes in the outside light: "Once we finished talking about the double skin, glass and iceberg, I likened the idea of composing a living façade, that would change, not only with light and shadows, but also with the ability to light up differently".

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France, 2005-2014.

Among his earliest memories, he must have been eight years old, Gehry clearly remembers his grandmother buying bags of chips for the stove. And again he returns to the feeling of happiness that those pieces of wood lying on the ground to build gave, apart from the worlds of cities and rings of roads. He enjoyed this in the same way that his memories took him to the times in which he painted alongside his father. At the age of 13, in the Hebrew school, he drew a picture of Theodore Herzl shortly which shortly after would be hung on the blackboard. The rabbi told his mother in yiddish that her son had goldene hänt: golden hands.

His studies of perspective, and later of ceramic at the University of California, pushed him towards architecture. From his time at university, he recalls how an afternoon of 1946 was at a conference that many years later would keep turning inside his head. The speaker was an older man with white hair: Gehry was fascinated by the power of design but paid no attention to his name. Years later learned that this was Alvar Aalto, the great Finnish architect whose work has influenced his.

During the 60s, in Los Angeles, he became involved in the California Art scene befriending artists like Ed Rushca, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Bell and Ron Davis, later to discover the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. He envied them for their creative freedom.

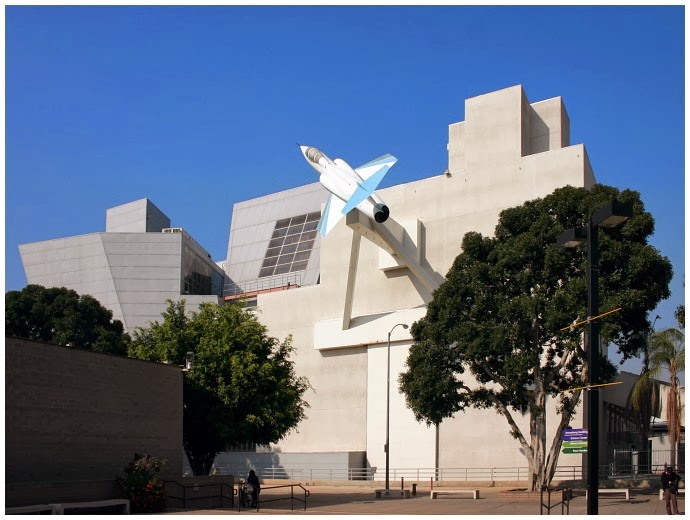

Aerospace Museum of California, Los Angeles, United States of America, 1982- 1984.

"Those artists did not feel bound by tradition, they were not out of a school, nor in the orthodox sense, deep intellectuals. They did what they wanted, manipulating materials, they had no boundaries," Gehry said. He came of modernism, a school of thought that mocks decoration. As a result of that, it was the materials that became his means of expression: he began using poor materials like cardboard - an influence of Rauschenberg-, corrugated sheet metal or chicken wire. Gehry wanted to convey this sense of newness and freedom in architecture. To try, risk, do something never seen before. He was considering the idea of mixing architecture without restrictions as concrete and immovable as the laws of physics. At this time he was mainly engaged in the design of housing within an architecture that has been called eccentric domestic.

Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, United States of America, 1977- 1978.

In the long documentary that Sydney Pollack does with Gehry on his life, there is a shot in which the two friends are talking in the kitchen of his home in Santa Monica. It was one of the highlights of his career. "When I bought it I saw that I must do something before we moved in. I liked the idea of leaving the house intact, and not changing it. It occurred to me to build another house around it. We were told that the house had ghosts. I decided they were to be Cubist ghosts. I wanted the windows to give the impression that they climbed from the ground". On the table they are speaking, the roof is broken into a large peaked window, and from there, at night, the effects of the car lights and traffic lights are distorted and the moon is reflected in the wrong place. He immediately began to hammer the roof of the bathroom, opening a gap with light as he could not see well in the mirror where he shaved.

Vitra Design Museum, Weil-Am-Rhein, Germany, 1987-1989, 2003.

Between 1987 and 1989 he built the Vitra Design Museum in Germany. It was a great break in his career, in a way, creating a new order. Gehry had planned an outdoor spiral staircase. He enjoyed the shapes he obtained by drawing but never thought they could be included in a building. He started playing with the staircase in the form of snake: he likened the contrast with the straight edges of the other volumes. He tried to express it through descriptive geometry but the construction was not accurate. He could not play with curved forms, he had to be restricted to the lack of freedom. The new movements he tried to express, took him to the computer. It is the 80s in California. And the outbreak of the software world came, of Steve Jobs at Apple, in his garage in 1976. In 1984 the company launched the Macintosh 128K, the first personal computer that used a mouse.

Parallel in time to the construction of Vitra, the Gehry studio was working on the project for the fish of the Olympic Village in Barcelona (1986-1992); a massive structure with sinuous stone forms, glass and steel. It was for this project for which they began working with CATIA, a computer program design, manufacturing and engineering by Dassault Systèmes to project complex shapes for the aerospace industry. This tool transformed the working system and Gehryś designs, facilitating the study of models with free and flexible forms and its projection in construction plans allowing it to be more daring, a little more and a little more... And so to support in its sculptural concept.

Bilbao, the Walt Disney auditorium, the building of DZ Bank... would not have been possible without this system.

GOLDBERG AND THE FISH

Gehry often described his work as fish. The idea of the fish is recurrent in his life and in his work, his sinuous curves appear endlessly in buildings, furniture and lighting designs. Its scales came one day by accident when working with a piece of concrete that fell and broke into pieces, those pieces made him think of the scales of a fish and since then he introduced them into his buildings.

"My colleagues were obsessed with Greek temples. You know, the postmodern era, in 1980 and after. Well, it was the great fashion, to reconstruct the past. So I thought: Greek temples are anthropomorphic. 300 million years ago there were only fish. If you have to go back, if one is so afraid to go forward, if you must go back, we can step back 300 million years. Why stay in Greece?" ... From then, he started drawing fish.

Fish lamp

In this way, the fish also became the memories of his toddler years. His grandmother bought carps that she kept alive in the bathtub of her home to prepare the gelfiltre, a traditional Jewish dish for the Sabbath.

The future Gehry, Frank Owen Goldberg, was the only Jewish child from school. From a young age he had to face the scorn of his peers. He was called fish face. In 1954, when he was 25 years old and had two daughters, he changed his last name to Gehry as he was pushed by his former wife, Anita, "It took me five years, when I was presented as Frank Gehry, I added, before I was Goldberg".

He also tells us about how he designed his own name, "Goldberg has, I'll draw it, a G descending, then o, l, d, b, e, r, g that goes back down. That is why Gehry has a G descending, and then e, h, r, with a y at the and end, also descending".

Growing up in a Jewish family and the study of the Talmud, the first expression is why?, it is the source that drives him to wonder every doubt in life.

With regard to image resource that comes into mind when thinking of his works, Gehry feels fascination for fabrics. The fabrics and its folds. In the early 90s, on a trip to Dijon in France's Burgundy, Gehry was fascinated by a stone fountain carved by a Dutch sculptor of the fourteenth century, Claus Sluter. In it,the monumental figures of the mourner's hooded monk sunder the tomb of Philip the Bold, causing him such emotion that he had to concentrate to study the chasubles that hid the heads of monks. The cloths eventually mutated to become the "horse head" of Gehry for the DZ Bank.

Claus Sluter, Tomb of Philip the Bold, Museum of Fine Arts, Dijon, France.

DZ Bank, Berlin, Germany, 1995-2001.

The influence of the weight of the fabric, its folds, are static; such as the tubular falls of the Tunic Charioteer of Delphi, or swollen by the wind, and the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Bernini, express not only the shape and movement of a rigid material, but - Gehry tries it - through those sculpted cloths, the expression channeled many emotions.

The Maggie's Centre was designed to recall the memory of his friend, the Scottish designer Maggie Keswick Jenks, who died of cancer in 1995.

This building is meant to be a meeting place for patients. It is the first building that, in 2003, Gehry projects in the UK. Seeing the sketches for Charles Jencks, husband of Maggie exclaimed: "This will be your Ronchamp" referring to the legendary Le Corbusier chapel in Franche-Comté. That ambitious comparison blocked Gehry who underwent a period of doubt and crisis in the rush of the plans. Until one day, Gehry himself says, that: "Maggie came to my dreams and said, 'Frank, what you did was a little extravagant". Thereafter, Gehry did not stop drawing. He found a sense of a building away from the spiritual connotations of Ronchamp, also more intimate: at the end of the day there should be a place where people go to feel comfortable and welcome "for a cup of tea and to mourn". So Gehry devised that tower as if it were a lighthouse and covered the main body with a corrugated roof. This time and for this coverage, his memory led him to take his trunk stored with images, a painting by Vermeer in which the undulating folds of her shawl reminded him of his friend Maggie.

Maggie's Center, Dundee, Scotland, 2003.

GUGGENHEIM BILBAO: CATHEDRAL OF THE 20th CENTURY.

The classic Greek spoke to us of the drawing, of the imago, the phantasma traced by the brush of fantasy, where the term comes to Castilian imagination. How was that day, at that hour, the head of Frank O. Gehry? What is surprising, says Frederic Migayrou, is his way of dreaming the work from scratch. Those early drawings, so mysterious, already contained a masterpiece. "Why did I have to spend two years designing a building that was already there?".

Gehry took Berta, his second wife, to Bilbao. Berta is Panamanian and Gehry wanted to dig into the bowels of the city, to find his character. She became his guide and his tongue to understand the Pais Vasco. He wanted to understand what was happening at the time. The Bilbao crisis, its economic decline, the disappearance of its shipyards...

Far from the light, Californian coast and urban, the first thing that puzzled Bilbao was its steel profile, their industrial cohesion mine, port, cranes, large ships coming and going, the trading. Everything seemed to colour the landscape in metallic shades, steel oxide clouds and mercury from its estuary. The reflections. The sounds.

Then, he did not stop until he knew something of its history, its art: the Basque architecture, political drama, terrorism. He fell in love with the city, its loyal people, the food, the pacharan and its green hills. They wanted to buy a house there, but were not well received. To the Gehry couple, Bilbao gave them the understanding that they were only interested in them to leave there museum there. No more.

Meanwhile, Gehry was dreaming of the building. He analysed the solar difficulty, wedged between the sea inlet, flown by the Salve Bridge. He wanted it to be "very Bilbao, very Basque, that hardness that I found so attractive". He had to leave the blackness of the estuary. The Nervion giant emerges from the waters as a fragmented spacecraft parts to fly with the wind of the Cantabrian Sea, luck of projection of a human dipper made of titanium tapes. After having climbed the hills surrounding Bilbao and having pointed out the exact location of the museum -"it must be there"-, Gehry looks at the place where the museum will be built, this time from the top of his hotel room. The journey begins from his head to the ink, from the ink to the titanium. His work is, as so often, intuitive. It is then when still on paper, with the letterhead of the Hotel López de Haro, he produces his first scribbles. The human brain is the most complex object in the solar system. Even today no one can explain how a kilo and a half of matter, protein and fat, can have ideas arise from it. From material to the immaterial.

Bilbao was a pioneer in building sailboats with a steel hull. The shipbuilding industry was based on steel. The Gehry museum resembles a futuristic sailboat floating on the river with all sails. Depending on the time of day, clouds, rain, night or sun, the building turns golden tones into silver tones. It is the effect of the titanium. Bilbao was, initially, designed in stainless steel. But all tests and models that were developed after the drawings did not give well on cloudy days. Against the grey sky of Bilbao, the stainless steel died in matt and dark tones. Back in California, Gehry found a piece of titanium in his studio that hung outdoors, when the effect of the rain turned it gold, as what happened in Bilbao, he cried out and gave an emphatic smile to heaven. This metal itself conveyed feeling.

With the Guggenheim, Gehry wanted to offer the city a new, eco building, which would be integrated into its own history and geography but would have a different impression. In which it would enoble the city and project an icon. "I think the communities crave an identity. The buildings have an identity in history. The Parthenon in Athens effect lasted for more than 24 centuries and lasts today. The Saint Peter in Rome has endured for more than five centuries. The people feel identified with buildings and return to them".

He would have liked to stay in Bilbao, contributing to the new design for the banks of the river. He had clear ideas, but he was accounted for. He had studied and understood the city and its architecture, he was not in accordance with the subsequent repercussions around the Nervion. It seemed that the true Basque spirit had not arisen: all those gardens, these excessive lights that had nothing to do with the merits of the Basque soul. Frank Gehry left part of his heart in Bilbao. Years later, looking at those first drawings he surprised himself: "One may recognise the signatures: at the end of this building comes from me. But this is different to everything I have ever done." Perhaps that is it.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, 1991-1997.

INTERVIEW WITH FRANK O. GEHRY

M.V: Most of the buildings are constructed from metal: the world of reflections, changes in light, night and day. The headquarters of the foundation Vuitton is another example, this time, transparent. You no longer build only in brick or stone.

Over the years your buildings reflect light, they absorb. What mystery transmits the light?

F.G: Natural light is free so I always say we should use it. We know the path of the sun and the moon and we know how light plays with shapes, building shapes. I don’t know about the mystery part.

M.V: What is your favorite moment in the process of creation, the most exciting? Is it the first drawing, the final model?

F.G: Working with the client to understand their needs, their dreams and to help them realize it. The technical stuff we do brings care in constructability: from care in budget control, care in responsibility to energy issues. We also respect neighbors and work with contexts.

M.V: In the history of architecture, religion also claims its space. In Spain, we have examples like Córdoba: on a Roman temple a Visigoth church is built; on this, the Omeyas construct the actual mosque; and early sixteenth century, a Christian basilica was added to the Muslim center construction. In the early years of Frank Gehry, a large space is occupied to Hebraic studies and patient Talmud reading. Among his buildings there are auditoriums, hospitals, warehouses, banks and especially museums.

Would you have liked to face a great religious monument?

F.G: Yes!

M.V: Julian Schnabel, his friend, says that Bilbao has the proportions of Luxor.

Have the architectural proportions varied since then?

F.G: Yes. That architecture exudes power. Today we try to exude friendship, community, and positive feelings.

M.V: Your creations seem to ride more and more towards lightness: do you remember Don Quixote, charging at a gallop against windmills 1991-1997. Its buildings are wrapped by metal sheets or candles that go out flying. We think the 12 candles of Paris, or in the Rioja winery as the headdress of a woman made of metal coloured ribbons that can fly among the vineyards. You are an admirer of Bernini recognizing the way which his paintings seem light, malleable, overblown by the wind: the Ecstasy of St. Teresa.

Will this architecture endure this obsession? Up to what point, for you, is lightness inseparable of beauty?

F.G: When it loses gravitas.

M.V: It has been over 20 years since the Guggenheim of Bilbao was built. You have created the museum and have converted it into the symbol of the city, the great transformer of Bilbao. The locals have been given the luck of the identity with its Guggenheim museum.

What is Bilbao for you today?

F.G: Bilbao is a place I cherish. The work led me to many friends. The one person who seems to be left out of all the questions is Tom Krens. Tom was director of the museum, was my partner in developing this project and deserves a big credit for his vision and his trust in me.

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

It was Hermann Hesse, together with a few other authors, who showed me from a very early age that literature is the refinement and perfectioning of life that is achieved through the kind of internalization often found in fine art. Internalizing does not mean reducing narratable external events to their minimum; rather, it means combining a series of events with a specific narrative message, within that apparent stopping of time that, again, we often encounter in fine art.

Hesse’s novels and short stories do not simply reconstruct events; they explore a wide range of existential and spiritual meanings through allegorical mediations and myths.

Many of his works show us entire new worlds and periods of time that seem to have never existed. His anti-heroes are symbols of misfortune, thrown out and left to rot in the ignominy of history from where they linger and stare back at us until our eyes hurt. It seems like Hesse wants to escape from the metaphysical-rhetorical optimism of classic European and Western humanism in order to defend the insoluble, inexorable union between pessimism and humanity. The way I see it, this is precisely what many of his allegories try to express — they are aimed at the source of a kind of happiness that is not quite of this world, but only because to achieve it requires a kind of inner transformation that intensifies the experience of the spirit. This is one way of extracting from Hesse’s books the spiritual richness within them, and of interpreting the self-reflexive, expressive mediations of his writings as new ways of understanding and practicing art.

It’s true that, today, many of Hesse’s novels feel rather distanced from our modern sensibilities: they almost feel like symbols whose role is to “represent”, at least in the Schopenhauerian sense of the word. The poetic distance of novels such as Demian, Beneath the Wheel, Narcissus and Goldmund, Rosshalde, Steppenwolf or Siddharta is, in fact, an ironic one, one which expresses a worthy critique of that unquestioned dogma: that there should be no pain in the world of representation.

In other words, the irony that is the anachronism of Hesse in our contemporary world is due to his positioning himself halfway between an allegorical short story about the soul of the modern European and a phenomenology of the disgraced conscience of the generic Human Being, who appeals to the highest, most seductive form of art as a parody secretly turned against itself. In this sense, detailing the exaggeration and the extremism so characteristic of Hesse’s spiritualism, this notion has a long history, because it reflects the intellectual disposition of those who grind their teeth in proud modesty while passionately seeking truth in beauty, as many philosophers and artists have done and will continue doing.

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

The international contemporary art fair, ArcoMadrid, will open its doors on February 25th, in association with Colombia, as an invited nation.

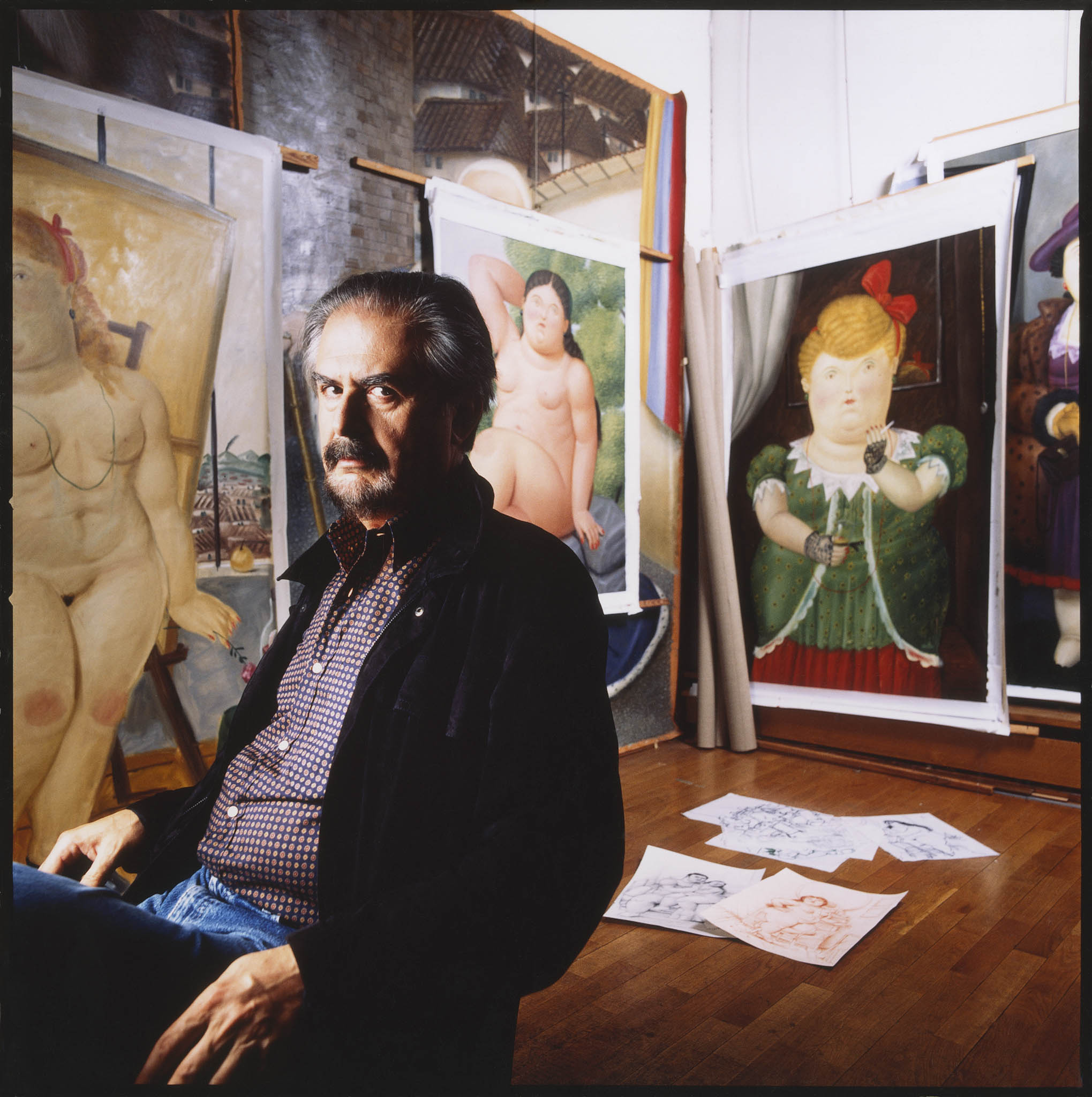

The Fernando Botero (Medellín, Colombia - 1932) art collection is one of the 50 most important museum collections in the world. As a palette, paint, and brush artist, his hands have never stopped working. His figurative art draws out the form and essence of his subjects, provoking a higher sense of sensuality, flexibility and grandeur. Reality is transformed through his imagination: sometimes into kindness, other times into scathing violence. The sculptures, paintings and drawings have created a relevant artistic production, whose objective is “to create a formal opulence.” These powerful figures, whether in marble or bronze, have been on exhibition in the most important venues in the world, such as: The Champs Elysees in Paris, Park Avenue in New York, The Grand Canal in Venice, and The Paseo de Recoletos in Madrid.

The still-lifes, the bull fighting, the circus, the religion and the eroticism make up an extensive theme rooted in Latin America — specifically in his native country — with a manifest skill in drawing and color. The beautiful and the violent combine together in the Boterian imagery that brings us closer to Colombia’ssoul through a nostalgic reminiscence.

Through his studies in Montecarlo, with views of the Mediterranean sea and his characteristic lighting, we can draw closer to the soul of this magnificent artist.

Elena Cué: His knowledge about art history is plentiful and has unquestionably influenced his art work. Do you believe that an artist can be complete without being influenced by culture?

Fernando Botero: A great artist is born from a profound knowledge of the tradition and problems of painting. However, there are many works in which freshness and audacity surprise, as can be seen in popular art and in certain examples of modern art.

E.C: You have said that “art is a permanent accusation.” Do you believe an artist has a moral duty to use his work to point out and denounce injustices in this devastating world?

F.B: The only duty an artist has is in the quality of the art. There is no moral obligation to denounce. An artist confronted with a tremendous injustice sometimes feels inclined to say something. Denouncing the situation is the artist’s choice.

E.C: Goya’s influence in your paintings is evident. The series of engravings, “Casualties of War” ("Los desastres de la guerra") totally reveals a dramatic cruelty and barbaric humanity. Your work includes a series about the crimes that occurred in the Iraqi jail of Abu Ghraib after the United States attacks in 2001. In this world of cyber-technology, events are ephemeral, since the new always replaces the old, in contrast to art which is powerful and timeless, making it more applicable. Why did you choose this precise series of crimes?

F.B: I did not choose this series of crimes, it was impossible to ignore them: just like Iraqi prisoners being tortured by Americans, in the Abu Ghraib jail - the same place where Sadam Hussein was tortured. Or, the violence in Colombia which left thousands of victims, on both sides, and displaced people, and since this happened in my country, it was especially painful for me.

E.C: Goya already stated that illustration didn't make barbarism disappear. Do you believe there is hope in this respect?

F.B: It is not possible for art to resolve situations which are basically political. The artist shows the situation that exists like a “permanent denunciation.” Nobody would recall the small village, Guernica, which was bombed, if it were not for Picasso.

E.C: Wisdom comes from a long life. What do you believe is the meaning of life?

F.B: The meaning of life is different for everyone. Some take on a hedonist attitude. For others, there is a necessity for spiritual or cultural fulfillment based on discipline.

E.C: You have already embraced the life of an artist in every possible way, in all of its complexities. What counsel would you give the younger generations of artists?

F.B: An artist is born like a priest is born. If they are born an artist, I would tell them art is not a game, it is something very serious which completely requires everything you have to give.

E.C: With an aesthetic technique as identifiable as yours, in which reality is expressed through a volumetric sensuality, what opinion do you have of the English artist, Beryl Cook, whose work reflects a seemingly jovial nature with an aesthetic sense very similar to yours?

F.B: This is the first time I have heard of Beryl Cook.

E.C: Your artistic production has beentypecast as “Magic Realism” determined by the importance of the myths in Latin-America, as well as the “New Figurative”artcharacterized by a return to the informal methods of figurative painting. Do you agree with this description?

F.B: Magic Realism, definitely not, because in my works nothing is magic. I paint about things which are unlikely but not impossible. In my pieces, nobody flies and nothing impossible happens.

Art is always an exaggeration in some sense; in color, in form, even in theme, etc… but it has always been this way. It is the same with the nature of some works by Giotto or Massacio, or the color of life as expressed by Van Gogh.

It could be a new figurative work. It is probable because we have inherited the liberty from abstract art, and we have a liberty in terms of shapes. Color and space involves thinking, not realism.

E.C: What literature works have influenced and helped in the type of works you paint?

F.B: I do not believe that other arts can influence painting - sometimes a vulgar image or a piece of popular art have more affect in the sensitivity of the painter than a masterpiece of literature. Since the very beginning I intuitively had an interest in exaggerating sizes.

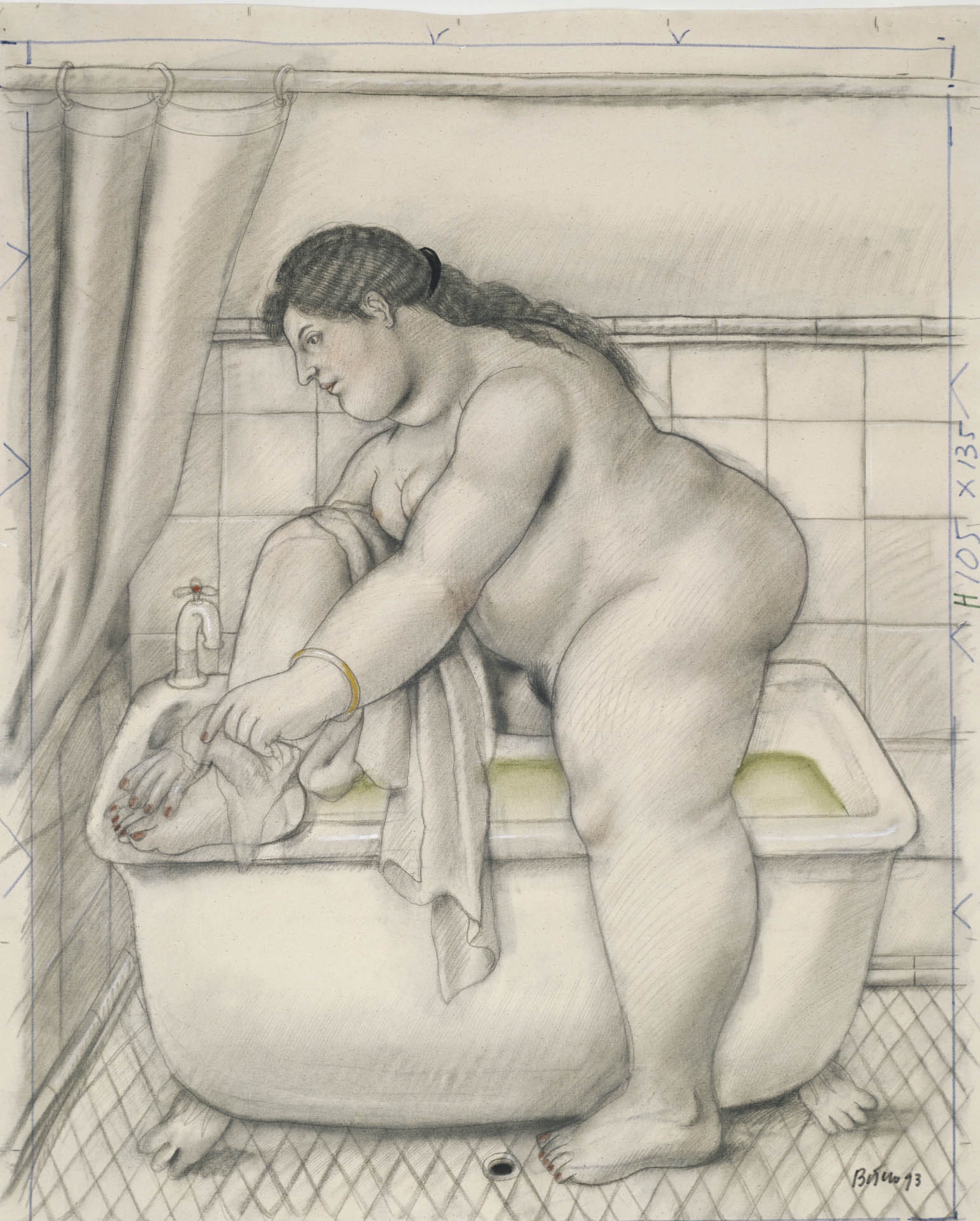

E.C: What importance does sketching have in your painting?

F.B: It is of utmost importance. Sketching is almost everything. It is the painter’s identity, his style, his conviction, and then color is just a gift to the drawing.

E.C: The generous donation of more than 200 works from your own collection to the Botero Museum in Bogotá, and almost 20 others to the Antioquía Museum in Medellín is exemplary.

What have your motivation and satisfaction been in this respect?

F.B: The donation I made to Columbia from my collection, and from many of my works, is one of the best ideas I ever had in my life. The public’s enjoyment is the best reward.

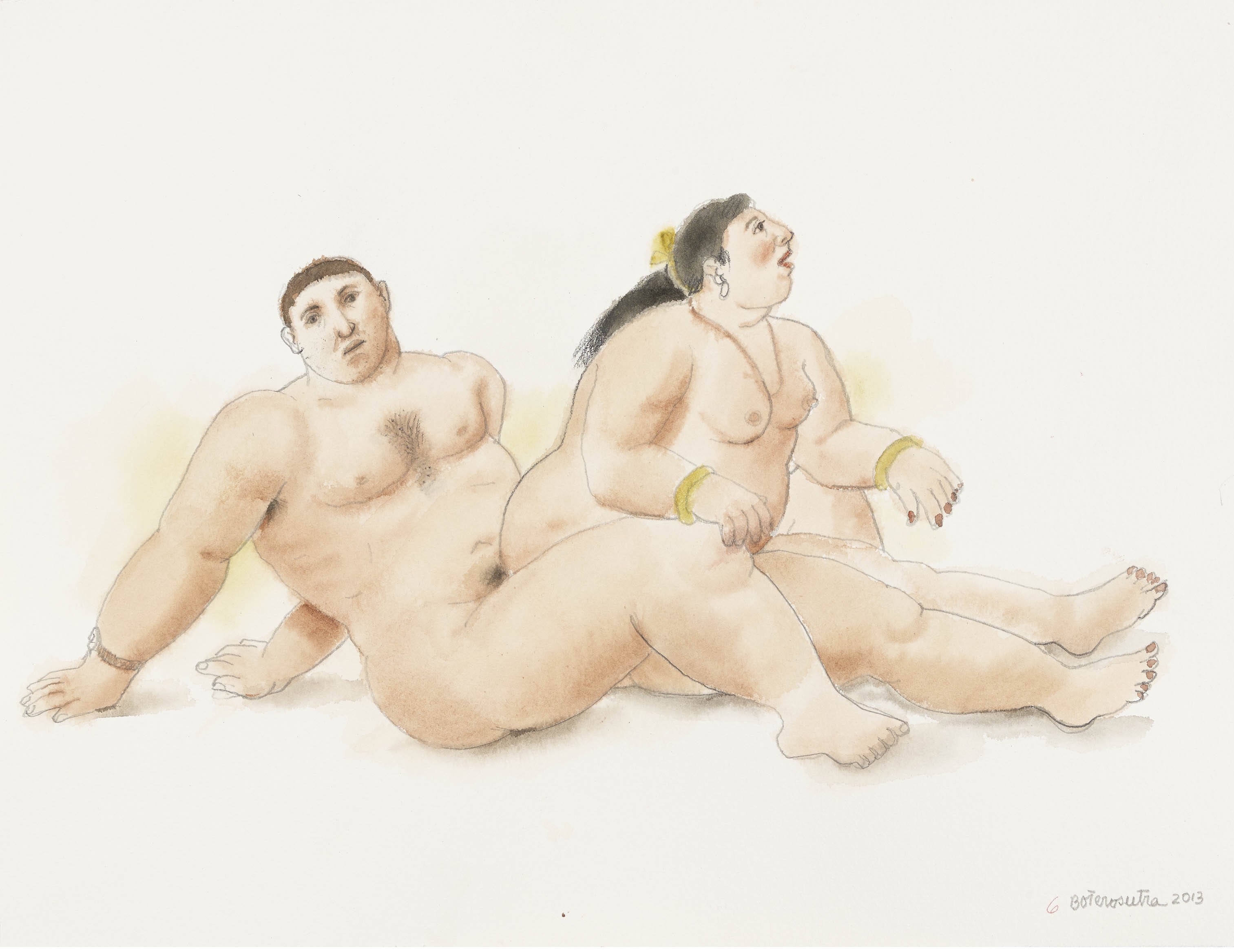

E.C: The millennial Hindu book, Kama Sutra, about the art of love in its spiritual and sexual fullness is reinvented by your imagination in Boterosutra. Which artists, from your point of view, have the best ability to represent love?

F.B: Eroticism has made great plastic manifestation all over the Orient, in Persia, Japan, India, etc. I did my Boterosutra series using more imagination than memory, trying as always to make the artistic expression more important than the theme - the rhythm of drawing, the subtle modeling, the application of color were the dominant elements in this series. The theme is extraordinary and unique because only in loving the human body can you make postures which could only be repeated in the circus.

E.C: Nietzsche, in The Birth of a Tragedy, writes “it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.” Is the art, as stated by Nietzsche, the metaphysical activity of life? For an artist like you, would this metaphysics be the only way we can make our avatars existence tolerable?

F.B: I have never read Nietzsche, but I do believe that the artist presents a world as the metaphysics of art. The artist presents, through his work in general, a more beautiful loving world that makes the “avatars of our existence,” as you said, more tolerable.

E.C: The study of the relationship of an artist’s biography and work has been a constant throughout the history of art. The Colombian history, social and political reality are expressed through your career. How do you see your country evolving right now? What vision do you have for spreading your national cultural identity?

F.B: The work of an artist, in its totality, is like a self portrait – in my country, in between great dramas, there has been an economic evolution and culturally positive advancements. I believe in the importance of the roots in an artist’s work. That ‘something’ that comes from the motherland is what gives works their touch of honesty.

E.C: What have been the most important moments of your life?

F.B: The most important moments of my life have always been connected to my work. They were moments in which I felt I accomplished something unexpected.

E.C: What do you have left to do?

F.B: Learn to paint.

- Interview with Fernando Botero by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

"No Comment" is the title for the opening of the exhibition of Chinese artist, Yan Pei Ming, at the Center for Contemporary Art in Málaga (CAC, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo).

Yan Pei Ming (b. 1960, Shanghai) grew up during the Maoist Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and worked as an artist to support the regime. Later on, he was part of the first group of artists to flee China in 1980. With great expectations, he arrived in France to study Fine Arts and earned a degree in that subject in Dijon, Paris and Rome. This geographical, cultural and artistic shift has had a substantial impact on his work.

The work of Yan Pei Ming stands out because of its decisively simple palette of red, white and black, and its forceful yet precise brushstroke line that sends us into his private world. His work primarily focuses on the portrait, an artistic genre that he depicts by emphasizing the psychological burden displayed by his iconic subjects. When you enter into the Parisian studio of this French-Chinese artist, you get the immediate sensation that you've not only traveled through the history of Western painting, but also that you've seen traces of the time period when he was working to support the Mao regime. All in all, Yan Pei Ming is, perhaps, one of the best examples of what it means today to be an artist in a global world -- where human beings, in a particularly dramatic way, are confronting experiences of solitude and death.

Elena Cué: You grew up in China in the midst of the Cultural Revolution and then relocated to France when you were 20 years old. You studied for five years at the National Superior School of Fine Arts in Dijon. What was the pictorial evolutionary process like going from the limitation of propagandist art to support the regime to complete freedom?

Yan Pei Ming: At that time in China, the influence on painting was from the classical tradition originating from the Soviet Union. It was propagandist painting to support the regime at that time. Those five years that I spent at the National Superior School of Fine Arts in Dijon were years of absolute freedom for me. From that moment on, I was able to combine what I learned from propagandist painting with a very individualized view of today's world. My freedom of expression is very noticeable in my current work.

E.C: How did you survive the East to West cultural shock, going from a communist regime to Mitterrand's Socialist France?

Y.P.M: In France, individuality was what stood out. In my opinion, the politics of François Mitterrand were, no doubt, socialist, but still liberal.

E.C: You graduated from the French Academy (Villa Medici) in Rome in 1993. What was your impression of Italy? What was that experience like?

Y.P.M: It was one-of-a-kind. I had an incredible year. It was as if I was in paradise, following the steps of all of the great painters that had come through this city. Those old masters help me to understand art from the past and they pave the way for me to make art that must be done nowadays. It was an unforgettable experience for me.

E.C: What memories do you have from childhood?

Y.P.M: My childhood was blessed, but lonely. Even from my earliest years, I was in my own universe. I always dreamed of being a painter because I could express myself without words. That's powerful.

E.C: You have painted your father several times, even dead. Tell me about him, please.

Y.P.M: I have always done portraits of my father, just as much in China as in France. I have captured him at different times in his life, and at different ages. My way of seeing him has evolved over the years. Also, there are oftentimes characteristics and defects that I've been able to find in the titles of those portraits. It's true that the way in which a child sees his father is not the same way an adult sees an older parent. I think that my portraits of him bring that to light.

E.C: You have depicted Mao on several occasions. What does that mean and who is Mao, in your opinion?

Y.P.M: He has been present in my work since I was a boy. His was the most copied and most widespread image in China. That left a mark on me. I also remember that my first lesson at school was entitled, Long Live President Mao! He is a mythical character.

E.C: Your 2009 exhibition, "The Funerals of Mona Lisa," made you the first Chinese artist to exhibit at the Louvre Museum. A huge portrait of Mona Lisa was accompanied by four paintings: two self-portraits depicting skulls from the cranium scanner, a portrait of your dead father and a self-portrait in which you pretend to be dying, which tops off the exhibition. Why is Mona Lisa crying? Can you explain this peculiar scene?

Y.P.M: It is a piece that I did in 2009 for the Louvre. It is a polyptych called, "The Funerals of Mona Lisa." I reinterpreted Leonardo da Vinci's portrait to be Mona Lisa crying at her own funeral and in front of spectators. My expression is similar to that of Marcel Duchamp after adding a few whiskers.

E.C: Your existential concern began at a very young age. The ongoing presence of death in your thinking is constantly represented in your work. Does the idea of death make you reaffirm life?

Y.P.M: A lot of emotional states appear in my work: my anxiety, my pain, my uncertainty. It is important for death to be present as well -- and, of course, energy and life. I don't need to sugarcoat or make things fancy. Paintings aren't for cuddling.

E.C: What worries you most about death?

Y.P.M: When I think about death, I rise up. From that point on, I work even harder to fill up on life. I'm not afraid of death. I'm afraid of no longer living.

E.C: Iconic paintings of art history and celebrities, your self-portraits and the representation of your father. Do you think that it is a way to transcend?

Y.P.M: I'm interested in everything, just as much art history as historical figures and the anonymous. The construction of history and sociopolitical issues interest me a lot. They all form our world as well as my painting.

E.C: Much of your work involves portraits, primarily figures, politicians or celebrities with sometimes serious and solemn expressions, yet kind and friendly other times. To what extent do portraits relate to the passing of time, as it does with Rembrandt?

Y.P.M: You're right. Rembrandt is a master portrait artist, especially the self-portrait. He's an important artist in my eyes. He's not the only one. There are also French, Italian and Spanish painters like Goya, El Greco, Velázquez and Picasso.

E.C: The revealing and fierce strength in your pictorial expression, combined with the huge sizes of the canvases and the drama of your simplified color palette of white and black or white and red really emphasize the emotional burden that's conveyed by those depicted. What are you most interested in drawing out from each character?

Y.P.M: In my opinion, the individual is the essence of humanity. A portrait allows the individual and their time period to be seen.

E.C: You stated on one occasion, "What interest me about a person are their attitudes, fears and lives, which are often tragic." Is the goal to feel less alone when facing one's fears and one's existence?

Y.P.M: I'd like the world to share my anxiety and my fears.

E.C: In your series on killers -- people that randomly snatch life away -- what is it that interests you about them?

Y.P.M: Animals have always fought to survive. I think that the same thing happens with man. Conflicts, wars and injustices are characteristic of man.

E.C: As an artist, where do you see beauty?

Y.P.M: To me, beauty is found in painting.

E.C: Your interest in Goya shows up in your reinterpretation of The Executions of May 3 or in Picasso, whom you've depicted. Have you been to the Prado Museum? What do you think of our Spanish masters?

Y.P.M: I've visited the Prado Museum several times and it has impressed me every time. When I was at art school in Dijon, one of my professors, Jaume Xifrá, made quite an impact on me. He was Catalan and spoke to me a lot about the Spanish painters.

E.C: Do you believe that there's a dividing line, or at least some difference between the Chinese artists that left China after the Cultural Revolution and those that stayed?

Y.P.M: There are differences between the artists that departed and those that remained. Without a doubt, their environments and lifestyles are different and therefore, their work is as well. In regards to myself, I would say that, as of today, I am a nomadic artist without borders. I am just an artist.

E.C: Your work deals with war and peace, money and globalization, capitalism and communism, with death as the backdrop. Is this your view of the world?

Y.P.M: My view of the world is pretty pessimistic. I don't believe in peace. Since the beginning of man, war has existed and it endures. It makes me think that man will continue fighting until the world is destroyed.

- Interview with Yan Pei Ming by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

Yue Minjun (1962) is considered one of the most prominent Chinese artists of our time. He was born in the Heilongjiang province, situated in the North-East of China and belongs to a generation of artists who grew up in the midst of the the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). This was a decade marked by repression and fear, with education based on idealistic beliefs and principles. Intellectuals were sent to the countryside to work in order to learn about agriculture and production, contributing to the revolution through physical labour. With the death of Mao in 1976 came a period of reform and dramatically reduced repression, which saw an explosion of a new form of art. This emerged amidst many huge social, political and cultural changes, following an art form largely dictated by grandeur and political propaganda. The '80s are well-known for movements including '85 New Wave, which saw a surge of young artists breaking free from the recent past with a strong freedom of expression and creativity. The '90s, in turn, have been characterised by the emergence of Cynical Realism and Political Pop, and marked the beginning of the appearance of Chinese art internationally. Subsequently, the ‘noughties’ became a decade characterised by commercial success. Each of these factors have contributed to a transformation in the way of thinking and expressing art nowadays.

Elena Cué: Have these historical, largely outward changes been accompanied by similarly radical, internal changes for you?

Yue Minjun: Yes, that's right. My experiences, feelings and some things from my cultural past have been essential for my current artistic creation. Furthermore, these experiences have reaffirmed my artistic concepts. In general, the Chinese give the impression that we are calm and peaceful people, nothing eclectic or categorical.

E.C: How did the free art of your generation in the 80s and 90s errupt after the Maoist ruling?

Y.M: I started drawing at the age of 10, and, initially, during that learning process and the visual images of the time I was greatly affected in a different way to how I saw after the 80s. However, if you are an art lover, your interest will grow when you begin to understand why an artist paints in one way or another. Then, your interest grows into a deep curiosity and uses this as a tool to gain further knowledge, with a constant evolution towards personal growth.

Although a cultural and artistic system in China exists, with the introduction of foreign art the change was shocking.

E.C: What memories do you have from your childhood and what has influenced you?

Y.M: Many things have influenced me, especially from a visual perspective, because what I perceived in those days - or what I remember from them - have been transmitted to my painting as one of the most important factors of expression.

In fact, in many of my works we can trace influences of the origin of propaganda painting, which emphasises the influence of the Cultural Revolution in my memory. For example, there are rows of heads that appear one after another, that undoubtedly offered transcendence in my past.

E.C: He has been considered to belong to the Cynical Realism movement, first described by the critic Li Xianting in the '90s. This came about in response to the tragic consequences of the student and intellectual protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989. These resulted in Minjun moving to a colony of artists in Hongmiao, situated in the Chaoyang district on the outskirts of Beijing. In 1989, an exhibition here by Chinese artist Geng Jinay, depicting his own face laughing, influenced Minjun’s work. And in 1993, Minjuin too began to use representative self images in his work - capturing himself in a frozen moment of laughter. These faces have since remained in all of his work, becoming an unmistakable sign and trademark of his artistic identity.

Joking, irony, mockery, humour and pleasure… Laughter manages to lighten tragedy and pain, acting like a remedy against helplessness; like a safeguard against the imposed cruelties of reality on the sanctity of life; a clarity within solemnity; acting to undo the natural urge for power, that is Nietzsche's concept of a will to power. Laughter acts as an antidote to our anxieties and concerns, as a symbol of protest… Laughter is a powerful tool encompassing many meanings.

What does laughter represent for you?

Y.M: In my work, laughter is a representation of a state of helplessness, lack of strength and participation, with the absence of our rights that society has imposed on us. In short, life. It makes you feel obsolete, which is why, sometimes, you only have laughter as a revolutionary weapon to fight against cultural and human indifference.

E.C: Minjun's international recognition came in 1999 when he was selected alongside other artists to be part of a show directed by Harald Szeemann for the 48th Venice Biennial. This saw a series of sculptures used in clear reference to the Terracotta Army of Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of a United China; these are known as the warriors of Xian, with each of the warriors with a distinct face and identity. The individuals in your work are, by contrast, all smiling self-portraits.

Having grown up as part of a community, are you now using your work to try to empower the individual?

Y.M: Actually, the terracota army of Qin Shihuang Emperor, or The Warriors of Xi'an, are symbols representing feudalism. Then, the individuals are actually immersed within an expression of the army. Of course, if you look very closely, each one has a different expression; but if you reflect from a collective point of view, the image of each sculpture is projected more weakly.

Inspired by this historical work when I started to create my own sculptures, I trusted that using the same person and the same expression would portray the disappearance or absence of the individual more accurately.

E.C: Democritus, the Greek philosopher belonging to the pre-Socratic school of thought, was known as the "philosopher who laughs", owing to his knowledge that reality cannot be reversed and that laughter is the best tool we have to help us cope in life. On the one hand, this represents an accepting of our reality, thereby stripping it of all seriousness. On the other, however, this serves to help us make sense of our own existence.

Do you believe that man should use this as a weapon against the unintelligible nature of our existence?

Y.M: The laughter could be a perfect marriage with feeelings. If we have the capacity to smile throughout adversity, then our presence will become stronger, tolerant and diverse, both for the artistic culture and for the majority.

E.C: Some of Minjun's works use icons in reference to key works throughout the history of art, including Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix, The Third of May 1808 by Francisco de Goya, and the Execution of Emperor Maximilian by Manet, inspired by the Tiananmen protests.

To what extent has your work been influenced by Western painting? Does the laughter in your work represent any negativity or criticism?

Y.M: The influence was very big in the 80's, thanks to the reform and the opening up of China, it came to us with the impact of a variety of foreign cultures. At that time, I was studying painting and I had the opportunity to be in touch with these works, which is why external influences were so relevant to my artistic creation. In my evolving expression there is an important part of my old work that is evocative of realism, which, at the same time, examined important questions such as the revolution, social reforms, definitely, as well as passion for life. And then I was getting to know artists like Picasso, and I was approaching Western painting while reflecting on visual evolution.

I think representation like that, in a more popular and simple way, my works will generate a more comprehensive meaning, both for the Chinese and the Western viewer.

E.C: Do you use laughter as a tool for criticism in your work?

Y.M: Yes, that's right. That's why I choose to paint laughter, to comunicate a sense of pleasure and happiness, but actually, it hides a double perspective of drama and suffering.

E.C: What are your sources of inspiration and where does your aesthetic come from?

Y.M: Actually, my Western influences have not come in the form of aesthetics or techniques, but rather in the form of iconography. Ancient Western painters knew and used this form of enlightenment in their painting, which also have many different interpretations between the West and China. Therefore, I have also practised the use of iconography to portray the interpretation of what I actually want to express.

Regarding the aesthetics and techniques used in my work, one can appreciate a ceratin simplicity, referencing my training at University. A good example is my teacher, who graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts of China, learning the techniques of realism from the former Soviet Union, and France at that time. He also learned how to observe objects while influenced by Impressionism; he painted lights and shadows, etc. However, I make use of the techniques I learned through my work, no longer portraying spontaneity or thoughtlessness.

During the formation of my aesthetic style, beginning with my own feeling or point of view, I thought my work should be as simple as possible, without any handling; completely removing sophistication without altering the initial result. Actually, I claim that my work is directly perceptible, beautiful and candid, with bright colours in order to attract the immediate interest of the viewer.

E.C: At times you have said that each of your works are based on your feelings and experiences, and that you are by nature a pessimist.

Where does this pessimism come from and what has it led to?

Y.M: My pessimism comes from the sad desperation that I feel when I observe my own culture. I mean, the society that surrounds me, their way of life and my own.

E.C: Your works contain allusions to Communist iconography, to a consumer society or to historical moments, at the same time loaded with conceptualism. Tragedy and comedy are cleverly mixed in such a way that it makes it difficult for us to determine our feelings about what we are seeing.

How do you hope the public will approach your work?

Y.M: The direction of my work is allegorical between human nature and our own existence. Because I have noticed that, not only in the East or in China, people are constantly facing emotional conflict.

I want to show how the individual, through painting, must remain awake, and how we need a greater understanding of the basic concepts of nature and life itself.

My work dosen't try to overly dramatise, and not because of that absence of tragedy. I want to refer to what each person feels by their sorroundings, or to the past experience that has been left in them through materialism; this does not liberate the human spirit, it is a pressure that leads to slavery.

E.C: In 2007, Minjun's painting Execution became the most expensive piece of work ever produced by a Chinese artist. And last year, Cartier's Foundation for Contemporary Art held the biggest ever tribute to a Chinese artist in Europe, exhibiting almost 40 pieces of your work.

What has this international recognition and commercial success meant to you?

Y.M: For me, the social repercussions that my work had and the spread of them in the country where I live, has been very important because that generated my personal growth and my artistic recognition.

I'm glad to know that the majority of my work is recognised by a lot of people, and that contributed to the reflection and comprehension in the way the artist is used to comunicate with society.

E.C: What is the future of your painting?

Y.M: There have been major changes to my creation. Given the different influences during my life, such as the Cultural Revolution or the time of the reform and opening. Actually, the 80s onwards have been an important period, as an era of great social change.

Of course, these changes refer, in most part, to the growth of materialism. Afterwards, I became more interested in discovering the origin of laughter in my work. Why are you laughing? Why is there this expression of laughter? I have come to understand that it is my own traditional culture. As a result of my reflection on laughter, I have related many of my works to the maze, which is integral to traditional culture; trying to express a feeling of confusion, loss and internal questioning that is in harmony with pain.

"Man alone suffers so deeply that he had to invent laughter" - Nietszche.

- Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -