- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Nicolas Berggruen (1961) is the founder and chairperson of Berggruen Holdings and the interdisciplinary think-tank, the Berggruen Institute, where scientists, economists, philosophers and artists from around the world engage and put forward proposals to tackle the 21st-century challenges facing humanity. Among the issues raised against the technifying, globalization and capitalist background of our time is that of how we see ourselves and recognize the other person in all their fullness from a moral perspective.

Nicolas Berggruen. Foto: Ernesto Agudo

Nicolas Berggruen (1961) is the founder and chairperson of Berggruen Holdings and the interdisciplinary think-tank, the Berggruen Institute, where scientists, economists, philosophers and artists from around the world engage and put forward proposals to tackle the 21st-century challenges facing humanity. Among the issues raised against the technifying, globalization and capitalist background of our time is that of how we see ourselves and recognize the other person in all their fullness from a moral perspective. On a plane beyond that of the spatial and temporal cultural relativism, Western and Eastern wisdom combine in his thought, which is articulated with practical proposals geared towards implementing good governance in a world undergoing profound transformations.

In 2010, his philanthropic conviction saw him make an important commitment to the Warren Buffet and Bill and Melinda Gates led initiative, “The Giving Pledge”: giving the major part of his wealth during his lifetime, through the Nicolas Berggruen Charitable Trust, to help solve some of the most pressing problems facing humanity. His passion for philosophy is readily attested to by his creation of the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture, comprising a million dollar donation to thinkers whose ideas and commitment help the world to progress in a more human fashion.

Co-author with Nathan Gardels of the book Intelligent Governance for the21st century, which was hailed by the Financial Times as one of the best books in 2012, he has just published, once again together with Gardels, his book Renovating Democracy (Nola Editores).

Could you start by pointing out the most serious problems affecting our Western democratic system in the age of globalization and digital capitalism?

To my mind, the good thing about democracy is that it gives everyone a voice and the bad thing is that it gives everyone a voice. In the past, we had a potentially more direct dynamic. We had dominant political parties and traditional media that were the editors or the filters who would be the intermediaries with the general public. With social media, this has disappeared because people, including politicians, talk directly to each other. This creates an incredibly dynamic environment. We could say super-democratic because everybody has access and everybody has a voice. This happens in advanced democracies like Spain and in places around the world where democracy is much more recent. It is actually a very liberating and wonderful thing, but at the same time, it all becomes very confusing because the traditional editors and filters are no longer present. On one side, it's an explosion of voices and a part of what democracy should be about. On the other side, that same explosion can lead to a wild situation in which it becomes harder to bring people together. As opposed to bringing people together, it can tear people apart. That is really the issue today.

So, how do you manage everyone's podium?

If we can bring all these people together to think about the issues, debate them, and ultimately vote on them in a reasoned way, then in the long term, it will be good for everyone. Another problem is the politicization of what should not be politicized, such as scientific issues like COVID, which is a health issue and should remain so. Scientists and relevant government offices should deal with certain things like health. There are two problems here: one, everything is politicized, and people don't want to listen to and trust health authorities, and two, in today's democratic world, there is less and less trust in government. This is a profound problem in the U.S., where trust in government has decreased, and it has become a vicious cycle because this lack of trust makes it more difficult for the government to function. This, in turn, makes it less attractive to work for governments, so you have less talent. A lack of talent means performance suffers, and when this happens, people like the government less, which makes sense. And it goes down and down from there. So democracy, in a way, is undermined from within. In short, what we have is a domino effect.

You highlight the impact of the information revolution and social networks on governance and how social problems are reduced to slogans that spread among those who think alike instead of using argumentation and dialogue to reach a consensus. Could you tell me more about your ideas in which the IT sector can help innovate today's democracy?

There are two aspects to this. One is that there should be innovation in governance, and the other is the management of social networks. In terms of innovation, the idea would be to have citizen forums debating different issues and then recommending their conclusions to voters, governments, and bureaucrats. The problem we see is that the most engaged people are the most vocal and not the majority. This is the problem with involving people digitally. On the social media side, the issue is that we need an editor. The question today is, who? To take an extreme example: in China, the government is the editor. We don't want that. In the West, the editors right now are the social media platforms - Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or Meta, for example. Since they are not necessarily the best editors, the question becomes, who is? Is it the government, and to what extent? Europe has regulated technology platforms, although this hasn't helped the much-needed editing process much. So, will the citizens themselves edit by getting involved in a different way? There have been similar phenomena in the past, and over time society has managed them. The solution will have to be a combination of government regulation to make information more transparent and, as the most popular publications are the ones that get the most attention, platform regulation to reduce the connection between popularity and distribution.

As a result, a polarization of representative democracies in the West has produced an institutional crisis leading to the emergence of populism and nationalism. How do you feel about this in Europe?

I think that, unfortunately, populism is on the rise. Northern Europe is more right-wing, and southern Europe is more left-wing, but it is a reaction in both cases. A reaction, I would say, born out of frustration, anxiety, and fear. Fear of the future, fear of change. We have had decades of globalization and technological advances. Advances go at a digital pace and are probably too fast for humans. People become fearful. They don't want to change, and they don't want anything new. They want to go back to what they consider to be a better and very often traditional past. So they react politically and adopt a very marked attitude towards the left or the right. It is an instinct of fear, and it is simplifying things because most people would like to believe in something that inspires them, that is quite simple, and allows change. Today's big problem is that the extremes, left and right, which are the edges of society, are hijacking the center. Even if we have ten or fifteen percent on the edges, they become so powerful and their voices so loud that the majority of the center is hijacked. People have always said that democracy is the tyranny of the majority, but what has happened and what is perverse is that, in many democracies, it is the tyranny of the minorities because their voices stand out more, not only in Europe but in all democracies.

Another of humanity's great challenges is reversing the climate crisis and the loss of biodiversity around the globe. The Berggruen Institute is working on this. Having seen the G20 Summit and COP26 recently take place, do you think we are in time?

We are late. And the planet doesn't wait, so I think we are super late. The question is, how do we deal with a planetary crisis that we are all, including governments, aware of? Look at COVID, we had a global health crisis, and nobody cooperated, every country for themselves, in essence. The same issue is happening with climate change. There is some cooperation and some action because governments and civil society are aware and afraid to the point where they are beginning to take action, but not enough. Market mechanisms such as carbon credits and taxes need to be adopted without a doubt, and there are technological advances that will help, but it's a gamble. Will they get there in time? We are gambling with the planet. I would say the political will is there in terms of intentions, but not necessarily action. We at the institute have been working on this for a long time. We are concerned with practical solutions. For example, we have a program that has been in place for some time between California and China. In the U.S., at least during the last administration, there was really no will at the Washington level to do anything, but at the state level, especially California, there has always been concern about climate or the environment. Nevertheless, you cannot only have climate action in the U.S.; you also need other big countries. Today's biggest polluter is China, so we need their participation alongside that of India and many others.

The Berggruen Institute also contributes through philosophy, art and technology to help us adapt to the speed of change affecting all dimensions of the human condition. Artificial Intelligence and Biotechnology are transforming the way we think of ourselves as human beings. What are your perspectives on this?

Some technologies such as artificial intelligence or gene editing will fundamentally, or potentially, transform the nature of humans. This may be the first time in history that humans can play God. We can self-transform. Through gene editing, we can transfer or change embryos, and we can change genetic lines. With AI, we will be able to potentially create other agents that are just as capable as us in certain areas or that augment our capabilities, and we can even combine the silicon base. So the problem is not only becoming more powerful. What is interesting, based on our experience, is that technologists show a very optimistic and very naïve attitude in which technology will solve everything and be good for everybody, but they don't look at the unintended consequences. We also see that the government lags way behind, especially in the U.S. They don't understand the technology. So what we have tried to do is to have an active dialogue between policymakers, scientists, technicians, companies that produce these things, economists, philosophers, and artists who all have totally different views. The idea is simple: we need philosophy for technology.

To this end, you have created the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture, endowed with one million dollars. This year it has gone to the Australian philosopher Peter Singer. Can you explain why he was chosen? You could say it's akin to a Nobel Prize for Philosophy.

Thank you, this is exactly the aim. We started the prize five years ago to say, listen, philosophy and thinking are just as important as economics and physics. Therefore the idea is a little bit, as you say, like a Nobel Prize for philosophers. What we have been doing for years is awarding prizes to different people. This year the jury selected Peter Singer, an Australian philosopher who argues that although humans are wonderful, the world should not be so human-centric anymore. We affect the planet, as well as others, including animals, and we have got to have respect for other species. Among ourselves, we've got to treat each other as human beings, and we have to treat other species with respect as well. It all boils down to responsibility.

Nicolas Berggruen and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2019.

What does the Berggruen Museum in Berlin, which houses the collection that your father, Heinz Berggruen, built up with genuine treasures of modern painting, including countless artworks by Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti, or more than 120 Picasso pieces, among others, mean to you?

Well, Spain is very well represented. Most of the works on display at the Berggruen Museum in Berlin are by Picasso. My father was from Berlin, and that's why the museum is there. He was passionate about art, and he collected works from the 20th century and very classical artists: Picasso, Matisse, Giacometti, Paul Klee, Cezanne, and they all ended up in Berlin. The family, which includes me, has decided that we should continue giving our help and support. We have continued to acquire works by artists that fit with the museum, including Picasso, and fortunately, the museum is alive. It's interesting because, honestly, in Spain, you have some museums that are also supported by families, like the Thyssen in Madrid or Picasso museums supported by the Picasso family. Berlin is a very dynamic city culturally, and we try to play that role with the museum.

To summarize: Changing the world through ideas - could you give me some final thoughts on this?

I very much believe that ideas change the world. At the very least, they change the way we think and function as humans. If you look back through history, you see that most of the things that happen to us as humans in our societies and cultures have come from a few thinkers, and this has been true forever. The big things that have shaped our lives have largely come from religious philosophers or thinkers. In the West, we still live in the world defined by Socrates, by Aristotle, by Jesus Christ, and, more recently, thinkers like Kant, Nietzsche, or Karl Marx. In the East, you have the same, you have Lao Tzu, and you have Confucius. You have different thinkers who have shaped the way China is functioning today. So the inference of ideas is totally predominant. I really think ideas shape the world more than anything else, so the institute tries to give power to people who develop ideas. Sometimes the ideas are great, and sometimes the ideas are terrible, but they shape the way we go. Sometimes you don't know for a century whether the idea is good or not, and very often, the most influential thinkers are not very popular. By the way, all the people I have mentioned were not popular at all during their lifetimes. Jesus Christ died on a cross, Socrates was condemned and poisoned, and Confucius was in exile, same with Lao Tzu. They didn't have a good time then, which is why we need to support them now.

- Interview with Nicolas Berggruen - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

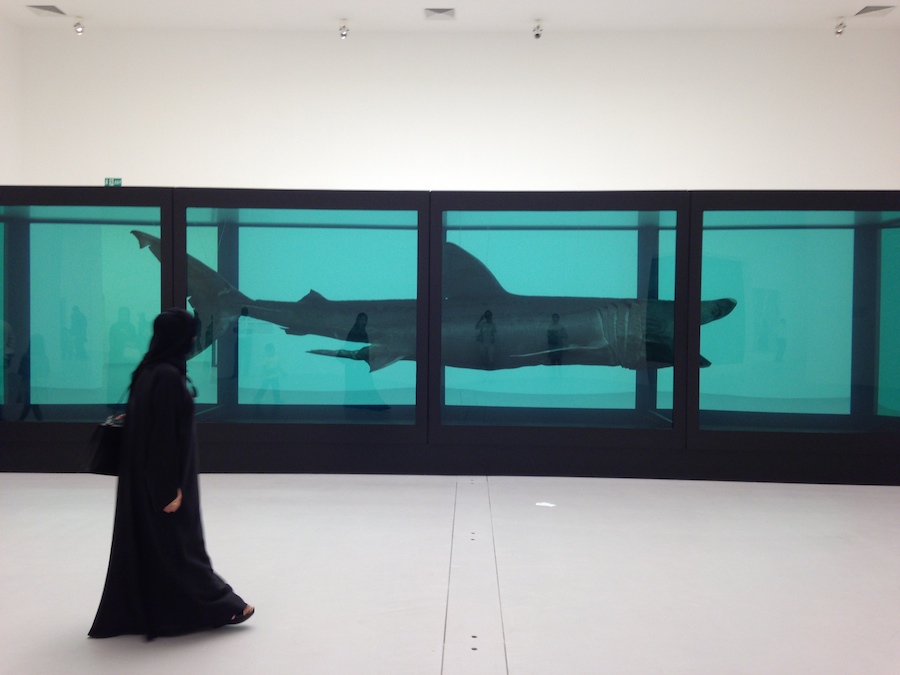

Damien Hirst (1965) began his artistic career as an iconic member of the Young British Artists group. The advertising mogul and gallery owner Charles Saatchi raised this group to the heights of world recognition and made Hirst its foremost representative, by funding and supporting his career. He was the one who managed to sell - in 2004 and for 9.5 million euros - Hirst’s tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. This particularly representative work forms part of his Natural History series, along with his cabinets of fish in formaldehyde.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

Damien Hirst (1965) began his artistic career as an iconic member of the Young British Artists group. The advertising mogul and gallery owner Charles Saatchi raised this group to the heights of world recognition and made Hirst its foremost representative, by funding and supporting his career. He was the one who managed to sell - in 2004 and for 9.5 million euros - Hirst’s tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. This particularly representative work forms part of his Natural History series, along with his cabinets of fish in formaldehyde. In these works, he sets a feeling of permanence, generated by his meticulous scientific organisation, against the ephemeral nature of life, which he also does with the minimalist style dissected cows and calves displayed at Tate Britain, which won him the prestigious Turner Prize in 1995.

Other important series of Hirst are his widely recognized Spot paintings: same-sized dots in random colours, named after pharmaceutical narcotics and stimulants. Or his Butterflies, named after a psalm that touches on Hirst’s favourite themes: life, death, art, beauty and spirituality. The mystery of death is shown through the final transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly, a symbol of the soul since antiquity, also seen in the rose and stained glass windows of cathedrals.

The Medicine Cabinets are yet another example of the philosophical concerns of Damien Hirst, an artist who has experienced the abyss of drugs, alcohol and tobacco, and who views art as therapy. Art, together with science is a social phenomenon of life in motion, a way of reflecting reality throughout history. In our current era, characterized by the triumph of technique, Hirst has succeeded in making his works into icons of contemporary art.

Alain Dominique Perrin, the creator of the Cartier Foundation, is holding Damien Hirst’s first exhibition in a French museum. We are referring to Cherry Blossoms, which displays 30 of the 107 works created by the artist over the last 3 years.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

You have recently gone back to painting. Has the fact your mother painted, in some way, determined your artistic career?

I suppose so, yes. Obviously, I already had a certain artistic instinct, but my Mum strengthened it when I was young, she encouraged me to draw and paint. I remember she would sit me in a corner with a pen and paper and when I would say I had finished the drawing, she would stick more paper to it again and again. Ultimately, I think it was a good thing, which helped me to think big.

At what age did you realise you wanted to be an artist?

It is difficult to say exactly when. I grew up in Leeds, Yorkshire, North of England, where nobody I knew was paid to do a job they enjoyed, rather, they would work for money doing any old job. For example, my Mum worked in an office and my Dad was selling cars for a big company. So, the idea was that a job was to earn money and your life was separate. With that in mind, because I enjoyed drawing, it never really occurred to me it could be a career possibility. I thought about becoming an architect as it allowed me to incorporate my passion for drawing, but it didn’t work. I was very messy when I was an architect. I signed on at the job centre when I finished my studies and that is when I had the idea to go to Art School. To be honest, the idea to become an artist came to me as a bit of a shock and it was only really at Art School that I realised it was a possibility.

At 16 you visited the anatomy department of Leeds Medical School to make life drawings. Death and decadence are themes that are repeated in your work. What meaning does death have in your work?

It is a complicated issue. I used to think that you could make art about death, but I don’t think you can anymore. Death is not art because art is life. I think I have changed as I have got older. As a human being, I want to confront things I can’t avoid. Death is one of those things. When I make art, I want to deal with those issues. That is the essence of art. Art deals with death. I think art is a light in the darkness.

Damien Hirst, Relics, Doha. Photo: Elena Cué

Can you tell me about your exhibition Cherry Blossoms at the Cartier Foundation in Paris and if the pandemic has affected your work in any way?

Absolutely, I think they are pandemic paintings. In my case, it got to the point where my work was very solitary. Before the pandemic, I dedicated 10 years of my life to Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, which involved working closely with many people, teams and fabricators. It involved very complicated things with different nuances in motion. After, I went on to paint with a few assistants. Then, I started working in a small interim studio just before Covid and when the pandemic hit; my assistants had to leave because there wasn’t any work. I began painting in solitary. Actually, I was very lucky to have the studio because when Covid came, I did not have to stop painting. Cherry Blossoms is a result of that. It is somewhat strange that such darkness brings such light and brightness. In reality, hope is one of the key aspects of the painting. When you are feeling hopeless... We have all felt and still feel great fear. Fear has a fundamental role when you want to make hopeful paintings. I honestly think it came out of that.

You studied Fine Arts at Goldsmiths College of Art in London. What was the most important thing you learned about art there?

I learned so much. One of the most valuable lessons was that there are no rules. Once I made something that was very confrontational and messy, I just screwed things together randomly. It was half-sculpture, half-painting, crazy thing. I remember the tutor saying it was not very good and I told her that that was the point. She then said that I needed to be clear with my work, to which I replied that was the point, I was not being clear. In the end, she agreed the only worthy artists are those who sack off everything for their convictions. In that moment I thought “That is it.” That was another key lesson. The teachers at Goldsmiths were all working, well-known, established artists. In many Art Schools teachers are failed artists who tend to teach what art means through a very negative perspective. That is why, studying at Goldsmiths was so incredible, there you were treated just like any other artist. From day one they trained you to go out into the world. They also taught you other aspects of the art world, not just its function. We were forced to justify everything and question everything. That was really important.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

In the 80s, you and some other students organised the Freeze exhibition, which caught the eye and financial support of the publicist and gallerist Charles Saatchi who, along with the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, elevated the group of Young British Artists. What did this collaboration mean to you?

There was a lot of exciting art at our college but there was not a place to fit it into the art world. We knew that no gallery wanted us, so we decided to create our own gallery. That was a turning point. We thought that we stood more chance as a group than every man for himself. It was a really exciting time. One of the lessons I learned at Goldsmiths is that you cannot paint, put your painting in a corner and wait to be discovered. You have to be more proactive. I wanted an audience and I had to find it. At Goldsmiths I realised you should not wait.

Do you miss collaborating with other artists?

I still have very good friends from those days. All the artists in that group were amazing, like Sarah Lucas, a phenomenal artist.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

Your admiration for Francis Bacon in your early days is well known. You stated that you stopped painting when you realised that your paintings were “like bad Bacons”. Which artistic technique do you feel most comfortable with now?

I enjoy painting a lot more now. I had a fear of painting. It was a question of confidence. There were two problems: one was a lack of confidence and the other was that painting was no longer fashionable and involved many challenges. Today it is very exciting, much more accepted. Back then painting was frowned upon, it was very old-fashioned, and I was desperate to be innovative and revolutionary which I could not achieve by painting. That is why I came up with the Dot Paintings, which ended up being very different from Bacon. In my heart lies the same kind of darkness that I really like in Bacon, Goya, or Soutine. Since then, I have managed to find my own way to paint, and I am very happy with that. I remember when I was a student, I used to paint and wonder about what people would think of my paintings. I would never really get involved. Whereas now, I just don’t even think about it. Someone once told me the real tragedy in painting is much more intense than that in real life. Just painting and playing with colours, I really feel the highs and the lows of existence. It is a new place for me, but I am very comfortable there. Just like Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable which is a very traditional exhibition, but it is actually very conceptual. Like my last show at Claridge’s, The Pipe Cleaner Animals, which I am very happy with. It is so childish, fun, and amazing.

Which part of the creative process excites you the most?

The end. I enjoy the technology, people, and machines but I like objects in an empty gallery.

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, Damien Hirst. Relics, Doha. Photo: Elena Cué

At the beginning of the 90s your work The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a shark submerged in formaldehyde, marked the start of your Natural History series, a totally revolutionary concept in the world of art. How did this idea come about?

Most of my ideas come from the desire to describe a feeling. I was looking for an object to symbolise a feeling. I had seen Richard Serra’s sculptures at the Saatchi Gallery. They were enormous steel sculptures. I remember walking between them, thinking they could fall on me at any moment. I remember feeling afraid and running out. I was fascinated by the fact that a sculpture could provoke fear. It invites you in to then terrify you. This was the root idea. I was inspired by a lot of minimalist artists like Carl Andre and Donald Judd. I loved Sol LeWitt’s Boxes (Project Box, 1990). I wanted to create a piece similar to that of Sol LeWitt but with something real at the centre. That is how the idea was formed. I wanted a real shark, big enough to devour a human and incite terror. Those were the ideas buzzing around my head and that is how this work came about.

Damien Hirst, Relics. Photo: Elena Cué

With the Medicine Cabinets series, you commented: “science is the new religion for many people”. What is your religion, what do you believe in?

My questions of belief have perplexed me for years. It is very difficult to find something to believe in and it is very difficult to live without having something to believe in. My exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable was specifically about faith and the search for truth in a world of lies. I was brought up in a Catholic family until I was 12 years old. Then my mother got divorced and she could not practice anymore. Right when she needed it the most, it let her down. That is why I gave up on being Catholic at age 12. With time, I realised that concepts like God are very complicated for me. I believe there is nothing. I prefer the scientific approach. I like science, but it fails in the same way religion does. Religion gives you almost everything you need. Money is the bane of religion. That said, my belief in art is almost religious. I believe in magic through art. Any kind of magic is a religious act. If you believe in goodness or in hope, if you believe that hope can conquer fear, you have religious thoughts. I believe in art, where one plus one can equal four, five, six, seven or anything. Thanks to art, you can create much more than you have. So, I suppose those are my beliefs. It is hard to say I do not believe in God. I believe in art because it is very similar.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

In science, what is allowed today might be the mistake of tomorrow. Science progresses but art doesn’t...

I think science offers an incredible way to view the world, but it is not the only one. In my opinion, it lacks the emotional part. We need emotions in order to survive. Scientists are not emotional enough and religions are the exact opposite. We need a mix of both. It is funny, both science and religion use art in the same way that governments do, to sell their ideas. There is no way to sell an idea without art. Just look at all the art that was made because of religion. Even in science, pills have to have the correct shape in order for us to believe in them because if each of them had a different shape, nobody would believe they have the same effect. Everything must be sterile and perfect, perfect shapes, perfect colours and perfect packaging in order for us to believe that science helps us fight against death. That is basically science. Science is a religion that declares it can stop death. In my opinion, science offers us immortality and religion offers us the afterlife. Although, in the end, they are both bullshit. As for art, it doesn’t offer you anything you do not have, it offers you something that already lives inside you. That is the difference between art, science, and religion.

Damien Hirst, Relics. Photo: Elena Cué

Walking in Paris, Cartier Fondation, Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, Paris 14th, july 2021

Damien Hirst, « Cerisiers en Fleurs » – Le film documentaire

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

- Interview with Damien Hirst - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Recently inaugurated in Lisbon, Rapture, is the largest exhibition by artist and political activist, Ai Weiwei, (Beijing, China, 1957) described by The New York Times as one of the most important critical artists of our time, with his eloquent and unsilenceable voice for freedom. The exhibition title has various meanings; one is the “transcendent moment that connects the earthly dimension with the spiritual dimension.” Another is the “hijacking of our rights and freedom”

Ai Weiwei © Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

Recently inaugurated in Lisbon, Rapture, is the largest exhibition by artist and political activist, Ai Weiwei, (Beijing, China, 1957) described by The New York Times as one of the most important critical artists of our time, with his eloquent and unsilenceable voice for freedom. The exhibition title has various meanings; one is the “transcendent moment that connects the earthly dimension with the spiritual dimension.” Another is the “hijacking of our rights and freedom” and this significance may well encompass the definition of the artist’s own life. A life which began with the vital experience of anguish and rupture when his father, the poet Ai Qing, is sent to a labor camp with his family and subsequently exiled during the Cultural Revolution by the anti-right movement, instigated by Mao Zedong. A lot of the inspiration for his artistic creativity stems from examples of lives torn apart, like those confined to refugee camps, lives ripped of freedom, lives destroyed as in the human flow of emigration, cries from corruption and totalitarianism or of sorrow by the ease with which human rights are violated.

Could you tell me about your exhibition Rapture?

It is an exhibition that includes works dating from the 1980s to yesterday, just before the exhibition opened. It contains eighty of my works, many of them are major works. It is the biggest exhibition ever organized, approximately four thousand meters squared in total and includes old and new works, installations, films, photographs and videos. It is a collection of all kinds of different works.

Which of the pieces from your exhibition has the most relevant meaning to you?

Every single work has a certain meaning and no one piece could take the place of the most relevant for me. I could not select one specifically because they are all from different periods. To me, they are all important.

After all, your work is a narration of your life, it is your biography.

Yes, it is like a biography. It would really take a considerable amount of time to contemplate all the works due the numerous videos and movies. They do indeed tell my story.

Rapture. Ai Weiwei © Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

The most recent works in this exhibition are a reflection of your Chinese roots. What values did you learn from your father, the famous poet Ai Qing?

My father’s life was very dramatic. He was a poet who had a strong influence on Chinese revolutionaries. After the nation was established, he was criticized as a rightist and was exiled for 20 years. During all those years, he was forbidden to write. I think my father is important, he was always very open and positive in a very innocent way, which made him very strong, to the extent that even the political storm could not really change him into another person, he remained true to himself.

You use art as an instrument of social and political awareness. What do you think about artistic creations without a purpose?

I believe that to think of art as not related to reality, humanity and even human struggle is simply not art. At least, it is not the kind of art I would appreciate or even understand. Otherwise, why do we need art? Nature is much more impressive. If you look at anything from nature, from a leaf to water, you would notice it is much more complex and much more beautiful than anything an artist can create. Artists must create emotions and an understanding of who we are and what kind of society we are living in. Just like literature and poetry, there is always some kind of hidden intention. It is not just a string of empty words and vocabulary, that is impossible. Art has always been misunderstood as a decorative tool, as if it is trying to decorate some type of life, but that is nothing more than a misunderstanding of the function of art.

You use art as a platform to voice and help the less fortunate defend their human rights and freedom of expression, but what does art do for you?

What I receive from my practice is life. Life itself is a practice. Without practice, there is no life. It becomes me and I become what I am trying to be as a piece of art. I need to find a language to define my life. If I do not find that language, it is simply as if I never existed or I never had a life.

Rapture also presents your last documentary Coronation where you talk about China’s "ruthless efficiency" in the face of the pandemic. If compared to the leadership of other countries such as Brazil or India, it seems like this merciless management has prevented many deaths, suffering, economic dramas ...

If you look at the numbers, yes, China is very successful. At the beginning, they said there were only 3000 deaths, now there are 4000 but the numbers were never true. Yes, they controlled the disease but at the same time, they controlled people’s spirit, people’s understanding about life itself. People have the right to be free. The state should not have that kind of power, a military type of power to supposedly ‘take care of people’ but at the same time really unhinge them. There is no humanity in that. You cannot treat people like animals. The state has become over powerful but yes, I should say that it has successfully controlled the disease.

China deprived its people of their freedom but protected its nation during the pandemic. What do you prefer: freedom or protection?

Freedom is not an empty word. Freedom includes our individual consciousness and our way to protect ourselves, others, and society. The individual must defend their rights. The government has no right to tell people what to do. It can make suggestions and organize resources, but it is in no position to force people to do anything.

What do you think about the European Union’s support of Biden's request for a new investigation into the origin of Covid in an attempt to ensure it never happens again, as stated by the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen?

Firstly, you can never really find out what happens in China. It does not matter if you carry out an investigation or not. China, as a society, has a certain characteristic that will ensure many things will remain a secret and nobody would be able to find out. Not only in this instance but also in every other political disaster, they never reveal anything truthful. Of course, today, I think we should understand the nature of the disease to prevent it happening again and avoid it happening every year. This is the biggest disaster and China, as a responsible large nation, has the duty to tell the world what really happened at the beginning of this disaster. However, I am convinced they will not let anyone know.

You have been very active in raising awareness about the problems caused by climate change. What do you think of the recent commitment made by China and the United States to reinforce the Treaty of Paris and collaborate in the reduction of greenhouse gases?

I like it. It is a positive step in the right direction. If China really commits to it, it has the potential to be very efficient. This is something every politician talks about, however, it is very hard to measure what is actually being done. Each nation is at a different stage of development and therefore they have very diverse ideas on how to limit this kind of behavior or how to take action. Nevertheless, it is good they have started to talk about these issues.

Which image from the past year has impacted you most? Crematories on the streets of India, cemeteries in South America…

There are so many, too many in fact, so again it is very hard to select just one. There were simply too many shocking images.

The refugee crisis and the “human flow” of migrations are central themes in your work that you particularly want to accentuate. The dignity of the human condition is at the heart of your concerns. In effect, you grew up as a refugee yourself because of your father's situation. What positive aspects have you drawn from such a traumatic experience?

As you said, I grew up in China, in a way, as a political refugee myself, so I am always wondering how Europe is dealing with the situation. Now I realize Europe is trying to look the other way and ignore the refugee crisis. Personally, I am extremely disappointed by this behavior. Thousands of refugees are being pushed away and have lost their life in the ocean. That is a fact. A lot of children, women and elderly people are just being pushed away. They cannot even reach the border. And even if they do reach the border, they (the authorities) will not let them through. This is an unthinkable situation. I could never have imagined that Europe would be capable of that, but they really have done it and in plain sight for everyone to see. It has changed my perspective on our human condition.

What is your opinion on the agreement reached between the United States and Spain in favor of “migration carried out through regular channels and in a safe, orderly and humane manner" as stated by the Secretary of State Antony Blinken?

I think if state policy is only choosing to talk about the humanitarian crisis as a tactic, it is a hypocrite. The US is still involved in wars, selling weapons to many nations which should not even be considered as democratic societies. I believe the US is responsible, and should be held responsible, for many other humanitarian crises happening around the world: what happened in Afghanistan, the US relations with Saudi Arabia, and many others that are very questionable. Therefore, when they talk about providing humanitarian help, first, they should stop producing war machines and stop interfering in many regional problems, not to mention the many other problems they create.

Meanwhile, you have opened another exhibition Marbre, Porcelaine, Lego in the Max Hetzler Gallery in Paris. What vengeful work can we find here?

The show follows my activities from recent years. My porcelain and Lego works portray motifs related to the migration and refugee crisis, which could also be called a humanitarian crisis. The idea is to combine the well-developed tradition of blue and white porcelain in China with the modern practice of the material Lego to create a unique expandable strength.

Ai Weiwei, After the Death of Marat, 219. LEGO bricks 231 x 269.5 cm

- Interview with Ai Weiwei - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

The former vice president of the US government under Bill Clinton's administration, Al Gore (Washington D.C., 1948), is known worldwide for his efforts in the fight against human-caused global warming. In 2007 he received the Nobel Peace Prize as well as an Oscar for Best Documentary (2007) for the broadcasting of his speech "An Inconvenient Truth". Concern for global warming was something that had haunted him since his time as a congressman in 1976. As early as 1998, he had already proposed the launch of the Nasa DSCOVR satellite which became possible, years later, thanks to his efforts.

Author: Elena Cué

The former vice president of the US government under Bill Clinton's administration, Al Gore (Washington D.C., 1948), is known worldwide for his efforts in the fight against human-caused global warming. In 2007 he received the Nobel Peace Prize as well as an Oscar for Best Documentary (2007) for the broadcasting of his speech "An Inconvenient Truth". Concern for global warming was something that had haunted him since his time as a congressman in 1976. As early as 1998, he had already proposed the launch of the Nasa DSCOVR satellite which became possible, years later, thanks to his efforts. Although he beat George W. Bush in popular votes, he lost the 2000 presidential election he ran for as the Democratic Party's candidate. Al Gore, Prince of Asturias Award (2007), is also the political father of the Internet. In 1978 he coined the term "Information Superhighway" and in 1991, as vice president in the Clinton administration, he created the National Information Infrastructure (NII) on which the Internet was developed. Gore is a visionary who knew how to solve the human need for interconnection. Once this challenge was overcome, he migrated from technological activism to environmental activism, from human interconnection to the survival of our planet.

You have experience advocating against climate change both in government and now in your foundation "The Climate Reality Project". In your opinion, where is your work most effective?

There is no position with as much influence as the position of president. That said, when I was not able to become president, I felt grateful to have the opportunity to influence in other ways. Ultimately, the solutions to the climate crisis must come from changed government policies. That would be the most influential way to go about it. However, in order to persuade governments to change, there is a place for advocates in the private sector and I am happy to be able to advocate for the right solutions.

If you were currently in government, what steps would you take in your country to help reverse climate change?

Number one, I would eliminate all government subsidies for fossil fuels. Number two, I would put a price on carbon, which would require action by the congress as well, but I believe it is now time to test the support for that measure, because I think it is there. Number three, I would accelerate the phase out of internal combustion vehicles such as cars and trucks and replace them with electric vehicles. Next, I would encourage regenerative agriculture to sequester more carbon in the top soil and plant as many trees as possible. Finally, I would launch a major program to make all buildings and factories much more efficient, with better insulation, windows, lighting and much higher levels of efficiency.

The United States is currently the second biggest polluter after China.

Yes. China is first and the US is second.

More than 90 percent of scientists consider that the greenhouse effect is anthropogenic. What would your strongest argument be to convince those who deny climate change exists?

First of all, it is now 99% of scientists. It is also Mother Nature itself whose arguments come in the form of hurricanes, floods, draughts and other consequences of the climate crisis which makes what scientists have been telling us for decades simply indisputable. If they are still deniers after all this time, I don’t know what might convince them. There are still people who believe the landing on the moon was a hoax. There are still people who believe that the Earth is flat. It is pointless to waste time arguing with such people.

How do the interests of dirty-energy (fossil fuel energy) companies affect the solution of the problem?

Some of the fossil fuel energy companies, especially in the US, have been using unethical strategies to slow down the solutions to the climate crisis. They have been doing the same thing that tobacco companies have been doing for so many years: putting information out to the public that is false and inaccurate. Tobacco companies hired actors, dressed them up as doctors and put them on television to lie to the public and tell them there were no health problems with cigarettes. Some of the fossil fuel companies, especially in my country, have been doing the same thing. They spend a lot of money to give the public misleading and false information about the climate crisis. They tell people that it does not exist, that it is exaggerated, that it is not a serious problem. President Trump is one of the biggest violators. He is supported by these fossil fuels companies precisely because he is willing to lie to people about the climate crisis.

What does it mean to you to receive the Nobel Peace Prize (2007) for your activism in favor of the theory of Climate Change?

The most important meaning is that it gives me a better opportunity to convince people that we have to change. It was the greatest honor of my life, along with the Prince of Asturias award. Both of these prestigious awards are important to me, not for personal pride, but because it gives me a better chance to gain an audience.

What are the main contributions of the COP25 World Climate Summit in Madrid? Have there been any significant advances?

Not yet, but usually the advances come on the final day of such conferences so I am hopeful they will break the impasse that currently exists at the conference center, where I spoke this morning. I hope they will be able to prepare the blueprint for next year’s meeting in Glasgow where all 195 nations will be asked to make bolder commitments to reduce their global warming pollution.

Does reaching an agreement between nations signify success even if not all countries are committed to it?

When the entire world reaches an agreement, that agreement inevitably puts a lot of pressure on all nations to do their absolute best to comply. It also puts a lot of pressure on private businesses, banks and investors. In some ways, business leaders are making more progress than political leaders. The reason for this is that the customers of these very businesses are telling them that they want to do business with companies that are part of the effort to solve the climate crisis.

Your documentary "An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power" covers the dilemma presented by countries like India, that need to burn fossil fuels in order to generate the energy needed to develop its industry, infrastructure and to increase the well-being of its population. As a solution, you advised them to increase their investment in renewable energies. Has there been any progress since the Paris Summit?

Yes, there has been fantastic progress in India. The country has experienced a big change since the Paris conference. They have started building massive solar and wind farms. Their electricity prices are going down. The air is no longer as dirty because of burning coal although they have other sources of dirty air that they still have a real problem dealing with. However, their commitment to solar energy is helping them build a better future.

In a climate emergency situation, like the one we are in at the moment, what impact do the Amazon wildfires have?

The new president of Brazil, Balsanaro, is responsible for no longer enforcing the environmental protections that have limited the burning of the Amazon. He is giving a green light and it has resulted in a much more fires. The risk is that the Amazon will be picked apart and will lose its ecological integrity. Scientists are now very worried that it will flip into a different ecosystem. Instead of being a forest it may become a savanna. If that happens, it will no longer absorb as much CO2 so it will make the global problem worse.

As the Amazon belongs to Brazil, how can we balance taking care of the world’s lungs with the demands of a growing population that has its own needs?

Destroying the Amazon is not a solution to poverty. It is simply a mistake and an ecological travesty. One reason it is a mistake is that the soil in the Amazon is extremely thin and it will not support agriculture for long. What we are seeing is a lot of corruption with people destroying the Amazon, making a quick profit and then abandoning it soon after. The way to create prosperity and more jobs is to accelerate the shift to solar and wind energy and sustainability as a blueprint. That can actually create more jobs and more wealth in Brazil than could ever be done by simply burning down the rainforest. In addition, it is important to remember that in the twenty-first century one of the most valuable resources is the unique pull of generic information that is in the rainforest. Cures for cancer and other diseases are often found in the exotic forms of life that exist in more abundance in the Amazon than anywhere else on Earth. It is foolish to destroy all of this genetic knowledge without even cataloging it and trying to use this information for its great value in medicine and in the making of new materials.

The overall notion seems to be that the development of new technologies, such as solar and wind energy, is slowing down but your stance is different to that. Could you explain why you are optimistic about it?

Many people are surprised when they see the latest business statistics. Electricity from the sun is now the cheapest source of electricity. The second cheapest source is electricity from wind. It is actually not that uncommon for people to be surprised when a brand new technology develops quickly. It is now a repeated pattern in the modern world where all of a sudden our mobile phones, for example, become supercomputers. They become everything; they can even act as flashlights. You can pay your bills with them. There are many other examples of these new technologies that at first are expensive and awkward but then they go down in cost and become much more sophisticated. This is what has happened with solar and wind energy. Those who have not been a part of that industry, after a few years pass, they see the new reforms and are very surprised but the business people who keep track of this are not surprised. They have been expecting this and they have been investing in it. Now, these new forms of energy are radically changing the energy marketplace worldwide.

The technology for storing solar energy has also advanced.

That is exactly right. In addition to the fantastic improvements in the technology for solar and wind, there is now also a fantastic improvement in the technology of batteries that can store the electricity so that you can use solar energy at night and wind energy when the wind is not blowing. The cost of these batteries has also been going down very rapidly.

And how about here in Spain?

There is less use of batteries in Spain than in most other advanced countries. I am not quite sure why that is the case but I think that will soon change. By the way, Spain has one of the most fantastic resources for solar energy than any other nation in the world. Particularly in the southern half of Spain. The development of batteries along with solar energy can transform the energy markets in Spain and sharply reduce the price of electricity making all businesses in Spain more competitive.

Regarding radioactive materials, do you think the nuclear waste management can be done in a safe manner?

Yes, I do, but nuclear energy, in its present form, is the most expensive source of electricity that we have. It is being phased out in most countries. China is still building a few new reactors but most countries are not, mainly because it is so expensive. There are two other problems. The handling of nuclear waste can probably be done safely but it also adds to the cost. Utility companies are paying money into a fund that is supposed to be used for the careful storage for nuclear waste but it is going to require even more money if there are more reactors built. Another problem is that the experience and knowledge necessary to manage nuclear plants has been hollowed out. The graduate schools that train nuclear engineers have not been training many nuclear engineers because after Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi the acceptability of nuclear energy was damaged in the minds of the public. Germany, for example, cancelled its nuclear plan.

When Alliance 90 (The Greens) entered the German government, Germany reduced its nuclear plants by twenty percent but in return increased its fossil fuel production. Now Germany is one of the biggest polluters in Europe...

The answer is not to go from nuclear to coal and gas, but to go from nuclear to solar, wind and batteries.

Given the current climate change emergency and the fact that nuclear power plants do not polute the atmosphere, should we consider nuclear power as a temporary solution to the urgent need to reduce emissions?

Most of the business leaders in the utility industry have become discouraged about nuclear energy. If you are the CEO of a utility company making and selling electricity and you decided to build a new nuclear plant, you would consult your staff and ask questions. One of the questions you would ask is how much it would cost to build a new nuclear plant. The truth is there is not a single consulting engineer in Europe or North America who will give you an answer to that question. No one can tell you how much it will cost. A second question you might ask is how many years it would take before the nuclear plant is finished so you can start using it to make electricity. There too, no one can give you an answer to that question. It is discouraging if you do not know how much it would cost or how long it will take to build. The utility company’s CEO would say that he/she does not want something with that much cost, uncertainty and trouble. That is what has been happening and it is happening in Spain as well. You have some nuclear plants here that are 40 years old and they keep getting 5-year extensions. They actually do provide about 20% of your electricity. I could be wrong, but I think that is about right. They do play a valuable role but the future of nuclear power does not look very good unless innovators come up with a new kind of nuclear plant that is less expensive and safer to operate.

What is your opinion of the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg?

I think she is fantastic. I am a big supporter of Greta. I met her a year ago in Poland at the United Nations Climate Change Conference. I greatly admire her ability to speak truth to people in power. I think she is a remarkable young woman and I am her biggest fan.

Al Gore during his interview with Elena Cué

- Interview with Al Gore - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Does science distance us from God? Professor of Economic Structure and member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences Ramón Tamames (Madrid, 1933) delves into the cosmology between scientists and philosophers in the already longstanding quest for the Primary Cause or Higher Intelligence as origin of the universe. The title of his latest book 'Searching For God In The Universe. A worldview on the meaning of life' (Erasmus) gives a clue as to its contents.

Author: Elena Cué

Ramón Tamames. Photo: Elena Cué

Does science distance us from God? Professor of Economic Structure and member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences Ramón Tamames (Madrid, 1933) delves into the cosmology between scientists and philosophers in the already longstanding quest for the Primary Cause or Higher Intelligence as origin of the universe. The title of his latest book 'Searching For God In The Universe. A worldview on the meaning of life' (Erasmus) gives a clue as to its contents.

Are you searching because you don't have faith or because you do and you want to back it up with science?

Essentially, it's just a case of my keen interest in cosmology and how little I may or may not understand of advanced physics. I'm also interested in the origin of everything and the meaning of life. And it's not actually that I don't have faith. In fact, I don't really get involved with revelation or mysticism, the usual channels that lead to faith. I respect it, though. Actually, I had a Christian upbringing and I've never stopped experiencing "moments" in that regard. I'm not a practitioning Christian but there's always "that certain something".

Have you arrived at any conclusions?

Yes, in that physics doesn't have all the answers or that it does but in a somewhat fantastical way. For example, Hawking told us that the universe was born by chance from a quantum fluctuation that produced the Big Bang. Naturally, that explanation leaves us cold, because ... what's behind all that? Where's the sense to it? That's what I've always wanted to research because, at the end of the day, the notion I have happens to very closely match that of one of my heroes, Isaac Asimov, who says that we're a staged planet: we're here and we're being observed by someone seeing how we manage, what evolution we follow and how we behave.

Would you say that was the crux of your search?

Alongside the meaning of life, there's someone at work behind it all, a superior intelligence that ushered in the Big Bang, gave rise to the computer and set material and biological evolution in motion.

What would this God have to do with the Christian God?

The act of creation. Essentially, the 'fiat lux' of the Vulgate, or the Latin version of the Bible, means "Let there be light". Many scientists say they don't like the Big Bang Theory because they think it's got a theological context. They say it's like God from the Book of Genesis. But that's just them arguing for argument's sake because the universe has to have had an origin and the most logical one would seem to be that one. I think the Christian God is a Judeo-Christian revelation belief. I respect that and I don't judge it. That's the Christian God and the Son of God. But it's a revelation. I come from a scientific viewpoint and I understand that God, as a superior intelligent being, might have many human manifestations, one of them being that of Christianity but, personally speaking, I think that's the most exalted of all the manifestations – because we're very influenced by that whole culture.

Have you encountered God yet in this quest?

No, I haven't. In any case, what I don't claim is that a God will reveal itself via a voiceover going "Here I am". Everything to do with creation is so absolutely left-field that I've ended up agreeing with the Seven Wise Men, as reflected at the end of my book. Not by reason of a criterion of mere authority but because they were brilliant people who've spent a lot of time thinking all this through. But in any case, I sense there's a higher intelligence that governs everything.

To sense God through science is possible. But do you think it's also possible for there to be a scientific basis for God?

That's the exact struggle between deism – although I don't much like that term – and militant atheism, such as that esposed by Richard Dawkins, the biologist. In any case, there's no solid path of 'basis' via science because if there were, we'd all be living in unanimity. Show me that DNA contains four bases and how that's what all living things are formed from. And tell me that's God's alphabet. But it's a parable, not a reality. If there were any proof, there wouldn't be any controversy.

You say that, in the 1980s, many scientists adhered to the belief that evolution didn't happen by chance or necessity, but by way of a teleological principle, namely, that it has a finality.

That's something that's been argued since at least pre-Socratic times, for over 2,500 years. Suffice it to say the discussion is a permanent one. Aristotle was already saying of Leucippus and Democritus that they had to have been drunk as skunks because they were going around saying it made no sense, when everyone knew, including Aristotle, that it did make sense and that there was bound to be a teleology.

And what do you think?

I think it's an ongoing discussion that, in a way, opens up into the philosophy of the meaning of life. Kant himself, around 1790, wondered what the point of it all was, giving rise to these four famous questions: What can I know?; What should I do?; What can I expect?; What is Man? And that way of thinking is typical of the Enlightenment. And what is the Enlightenment? Well, according to Kant, it's reaching the age of maturity.

That's where we're at. If I could offer any definitive examples, I'd give them and be over the moon! Actually, I sent my book to the Pope and his Secretary of State replied to me with an autographed photo of him. Saying nothing at all.

Do you think there's less respect for institutuions, governments, beliefs, etc nowadays?

I think that's always happened. In the Century of Reason, Baron d'Holbach stopped believing in God and laughed at Christians. The thing is, sometimes it's been more tolerated and permissable than others. Nobody can doubt that in 16th and 17th Century Spain, anyone agitating too much in that regard got what was coming to them. In that sense, there's always been unrest. What's happening now is that people demonstrate more via social media, they're bolder, knowing full well that public freedoms and guarantees allow them to do so. The media are very much to blame for hypertrophy. They induce changes in the general mindset, no doubt about it, and things that were unacceptable in formal societies a hundred years ago are acceptable now.

How do you see the Spanish economy right now?

I'll say something that may seem like an exaggeration but it isn't. The economy is doing quite well and comparatively better than the rest of the European economy, despite the politics, because political instability is having quite an effect on it right now and despite the Administration, which I would call a great lumping monstrosity of a thing and an absolute disgrace. I'm not talking about the doctors, I'm not talking about the police, I'm talking about the Administration itself, the change in policies, in the fundamentals, and also, obviously, the bureaucracy because the problem with bureaucrats is not only that they cost us more and more money every day, but, as they have to prove they're useful, they delay and complicate everything.

So Spain is doing well ...

This country is doing well despite its Administration, which is a great lumbering monstrosity of a thing. There's the answer. And why is it doing well? Because we have the best entrepreneurs in our entire history. And our stock market, Ibex 35, is symbolic of this entrepreneurship we have. There'll be some doing better than others but that a group of companies does almost 70% of their business outside Spain means that they are competitive. That's what you have to recognize.

Which economic proposals do you think would be needed for improvement?

There’s no lack of proposals. And fortunately we have proposals that are very positive indeed, that come to us from outside the country. My opinion is that "Super Mario", aka Mario Draghi, has an impressive policy for European economic recovery and he hasn't allowed the Euro to go under. And I think there are many other recipes for success but they're being obstructed by the 18 ministers we have, the corresponding secretaries of state, the thousands of director generals, and so on.

You write that skepticism is growing about whether CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming. And you speak at length, warning of the danger we face in the short term in your book 'Facing the Climate Apocalypse' (Profit Editorial).

That's where most of the uncertainty lies, actually: the fact we don't know if we'll be in time or not. Someone well-versed in this, James Lovelock – who worked at NASA and is the author of the Gaia thesis – argues that Earth is a self-regulating organism and that at any moment Gaia's revenge might come, namely, to expel man and let evolution continue on, but without the human species. Perhaps that's a scientific exaggeration to make people wake up, just as the young Swedish girl Greta Thunberg has done, saying that climate change is humanity's worst and foremost problem.

The problem is whether we get there in time or not ...

I have my doubts, serious doubts. Not exceeding 2°C above the temperature benchmark set before the beginning of the Industrial Revolution as the main objective of the whole 2015 Paris Agreement is a pipe dream. What's clear is that we're continuing to accumulate greenhouse gases and that the symptoms are fatal not only in the Arctic and the Antarctic, but also in glaciers and droughts, etc. The problem is to get them under control before it's too late and Lovelock says we won't.

Why is it a pipe dream?

Because China will continue to emit greenhouse gases without curbing them until 2038. And the U.S. has also, theoretically though not legally, withdrawn from the Agreement. It's true that many of the states over there, especially on the West Coast, are doing an impressive job of reducing carbon emissions. But the point is that we haven't taken the problem seriously enough yet and the deniers are still out there. The Paris Agreement needs to be revised.

How can we decarbonize society and take care of the biosphere, without doing economic damage?

There's no problem there. The Paris Agreement, and all of its members meeting every year, more or less foresaw and saw to that. The last summit was in Katowice and, if nothing else, they agreed on accepted methods by which to measure emission reduction, which is no small thing.

I think the Climate Act, a good plan in the making, is a great start and we'll be opening some plants and closing others. And renewable energy is moving very fast. But we're still without a coherent plan. Teresa Ribera, the Minister for Ecological Transition, said to expect it by Christmas. I think the European Union is doing a good job. It has set some objectives that are attainable but the problem is whether or not they alone will suffice.

Ramón Tamames. Photo: Elena Cué

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Sidi, the latest novel by writer and Royal Spanish Academy member Arturo Pérez Reverte (Cartagena, 1951), has just been published. Sidi is the story of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, Cid the Champion, and where his legend begins: his leadership, his sense of honour, his courage, loyalty and dignity but also of pride, pillaging, blood and swords. A journey through time to that Spain of hard knock men with other ideals; men of courage and strategy in warfare, in waiting, in uncertainties ...

Autor: Elena Cué

Arturo Pérez Reverte. Photo: Elena Cué

Sidi, the latest novel by writer and Royal Spanish Academy member Arturo Pérez Reverte (Cartagena, 1951), has just been published. Sidi is the story of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, Cid the Champion, and where his legend begins: his leadership, his sense of honour, his courage, loyalty and dignity but also of pride, pillaging, blood and swords. A journey through time to that Spain of hard knock men with other ideals; men of courage and strategy in warfare, in waiting, in uncertainties ...

With the echo of the battle of Pinar de Tébar still sounding in my head, I talk to the author.

The 11th century, at the height of the Middle Ages, in a Spain of Moors and Christians. Sidi makes his living in exile. What is this novel about?

There are two fundamental narratives: the first is what our border was like in the 11th century, our Wild West. It was a very dangerous and unstable border, full of equally dangerous people. The second is a reflection on leadership: how a person is able to wield control, with the respect and command of an armed retinue of tough, dangerous men in a place that was no less dangerous. In other words, how someone is able to get others to follow him, even to die for him.

You say that there are many Cids in the history of Spain, some moreso than others.

But this one is mine. I wanted to tell the story of a Cid that hadn't been told yet, especially at the moment he took shape. I came to it with all the documentation and also with all of my own personal biography. I've poured everything I know about human beings into this kind of subject. The Cid looks at the world as I look at it: I have given him my eyes. When I speak of violence, death and blood, to a certain extent I have lived them all myself.

As a war correspondent and photographer, you've covered various conflicts such as those of Libya, the Sudan, Bosnia .... And as a writer, wars are present in many of your novels. Why this fascination with war?

It isn't fascination. I left home very young, with a rucksack and a few books, and went to a war. I learnt things in a single day that might otherwise have taken me ten years to learn. I was twenty years old and had a vision of culture that allowed me to interpret war as something more than a mere spectacle of barbarism. It was nurturing in an intellectual sense. I learnt about human beings, their behaviours, the value of things. War is horrific. I was rather more fascinated by the feeling of being close to the truth of what a human being is.

Behind the legend or the romance of the character lies the most terrible violence. In The Painter of Battles, you make a profound reflection on cruelty as an irresistible impulse. Is cruelty inherent to Man?

Human beings are a very dangerous animal, and yes, cruel. The point is that we want the world to be a certain way: that there be rules and behavioural norms as well as moral principles, an Enlightenment that made us change the way we look at the world, or a Renaissance. But the thing is that the world isn't like that. That is a tiny part of the world. As soon as you leave its confines, you add war. That's the real world. We think everything is stable but, when you have been to Beirut or Sarajevo, you realize that all it takes is a political, economic or social crisis for everything to fall apart.

What did war give you?

War gives you consciousness, a lucidity like that of a sailor who must always be mindful of the sea. And that certainty of disaster as something possible, that the Westerner has lost, our grandparents still had it. There was at that time a greater proximity to the reality of things. I've seen violence: I've seen killing, I've seen torture, and I've been friends, too, with people who did those things. And those same people who did horrible things also did, the very same day, great things. That gives you a very different measure of things. That's what I make my novels out of.

And this novel takes place at a violent time of terrible insecurity when survival was difficult. What do you think is the price we human beings have paid for the security we enjoy today?

We're more vulnerable. There's one thing in this novel that I've tried to make stand out and that's the fact that everyone spends a lot of time on the lookout because being watchful means living or dying. Nowadays, the only thing we humans stare at is our mobiles or the television. We don't see reality. The world is a hostile place often populated by sons of ******* and that is a very fair definition of what the world is. We pay a very high price for the false security we get from not looking at reality.

Now that you no longer take photos when dealing with war, what do you look at?

I look backwards. I have a rucksack full of memories that help me to live in a much more suspicious, much more lucid way, in the sense that you know what a dangerous place is, that even here we are in a dangerous place. That is why we can never relax and why we Westerners, instead, live lives of real deception.

You've been a man of action. What comparison would you make between the power of experience and the mental journey from your writing desk?

There are three ways to nurture and flesh out a novel: with what you've read, what you've lived and what you imagine. When you've lived a complex life like mine, with intense doses of extreme situations, that works for writing novels too. For example, if I am describing torturing someone in Falco, a trilogy of novels about a Francoist spy who is handsome and elegant but also a son of a ***** , when Falco tortures someone, I am drawing on my memories of Angola, on my own experience.

Swapping war for your writing desk ~ was that a radical change?

It wasn't radical. I left journalism in 1994 but I went through a period of adaptation. There were a few years that were difficult, more or less until The Painter of Battles, with which I brought that period to a close. I go sailing. And my substitute for war is the sea, the real one. On a sailboat in the Gulf of Leon in winter, I can assure you there's lots of action. I've changed, of course. There are things I can no longer do like walking 40 kilometers every day, in the blistering sun with no more shade than my hat. I'm 68 and my body wouldn't accept it.

Why did you close that period?

I once met a guy in Asia, in Bangkok, who'd been a correspondent for a Spanish newspaper in the 70's and he was an old alcoholic, frequenting prostitutes, etc. He was telling me about his life and I was thinking: one day I'm going to be like this guy. And I told myself I didn't want to end up like that. From the very beginning, I tried to create another parallel part of my life to retreat to when the time came. I always knew I'd leave, that one day all that would come to an end. We're usually told that human beings are good and that the world makes them bad. I think it's the other way round. Human beings are born with instincts that aren't bad, but very primal: keeping warm, eating, procreating, sheltering, protecting ourselves. That's what we sacrifice everything else to. It is society that, by creating a series of rules, civilizes us. But put us in extreme situations and the human being becomes very dangerous.

Sidi is a charismatic warrior who gets his supporters to follow him blindly into battle and brings about cohesion and understanding among very diverse people. For example, Moors and Christians united under him. What qualities do you think a leader should have? .

In a way, this book is also a kind of self-help manual on leadership. My idea was: why does a member of the lowest rank of the nobility who has fallen from grace into disgrace, a nobody to all intents and purposes, manage to become a legend who eclipses the names of the kings of his day? How does a man, at that time, get others to follow him and die for him? How does he achieve such loyalty, loyalty being the hardest thing to achieve in life? And I wasn't interested in him as the finished article but rather in when he began to become the Cid: the years of evolution, of exile; in short, when the legend begins.

Are there leaders today?

Yes, possibly. There always have been. But the problem, in my opinion, is that our times don't deserve these men. When we speak of virtue in the Roman sense, namely, of nobility of spirit and an elegant attitude towards life, of personal dignity and courage, you realize that today's world is not interested in that, doesn't want it and even rejects it. What's more, when the people of today come face to face with virtue, they mock it. Up against noble people who can't be matched, they ridicule them. The mediocre person tries to bring them down. And since they can't, they try mockery. Anyone can do it over the Internet, in 140 characters, on TV...

Laughter is a powerful weapon ...

The Cids, the personalities are there. Human beings constantly produce geniuses, artists and creators, heroes and firefighters, wonderful people willing to die for many reasons. They're people willing to sacrifice themselves for what they believe in. That bothers some people.

Do you think there's anyone left now who's willing to die for their country or an ideal?

Actually, I don't think the Cid dies for an ideal. He had a code of allegiances and dignity. I mean, what I was interested in highlighting about the Cid is that it's not about a person who sets out to fight for an ideal. He was doing it to put food on the table. He is not fighting first and foremost for the Reconquest (which didn't as yet exist in Spain) but rather because these were kingdoms where there was fighting between Moors and Christians. Besides that, he has no providential mission. All of that comes later. He had no religious or patriotic ideas, which is to say, he wasn't fighting for God or country.

But despite his banishment, he continued to pledge allegiance and respect to King Alfonso VI.

Do you know why? Because when you have nothing, when you are an outcast, expelled from the bosom of society – whether you are a criminal or a mercenary – and the general codes with which society protects itself stop working, you need to have something to respect: you need a loyalty code between your people and something else. Even marginalised people, even people who are moderately decent seek some kind of justification in order not to feel wretched.