- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Geumhyung Jeong is an interdisciplinary Korean artist with roots in the worlds of theatre, animation and dance. Her arrival onto the contemporary art circuit as we understand it is relatively recent and, in just five years, she has exhibited her work and presented her performances in such places as the TATE Modern and the Delfina Foundation in London, the Kunsthalle in Basel and the Hermès Foundation in Seoul. The themes that Jeong explores in her work resonate perfectly with the hot topics of contemporary art today but she does so from an outsider position that lends her an air of the ‘genuine ingénue’.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery

Geumhyung Jeong is an interdisciplinary Korean artist with roots in the worlds of theatre, animation and dance. Her arrival onto the contemporary art circuit as we understand it is relatively recent and, in just five years, she has exhibited her work and presented her performances in such places as the TATE Modern and the Delfina Foundation in London, the Kunsthalle in Basel and the Hermès Foundation in Seoul. The themes that Jeong explores in her work resonate perfectly with the hot topics of contemporary art today but she does so from an outsider position that lends her an air of the ‘genuine ingénue’.

As an artist focused primarily on performance, her exhibition ‘Spa & Beauty’, happening simultaneously in London and Madrid, is a reflection on this very concept. Whilst the London exhibition presents the idea of performance without her, in Madrid she performs the ‘demonstration’ and installation herself.

Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery

‘Spa & Beauty’ is a project commissioned by the Tate Modern in which the artist creates a slightly modified spa, perhaps one with that sense of “the uncanny” that Freud talks about. The installation consists of furniture and objects typical of a spa (a bathtub, a massage table, brushes, sponges, …), but Jeong gives it all a twist by including mannequin limbs and teleshopping videos downloaded from the internet that add other levels of meaning and aim to portray a society obsessed with physical appearance and wellbeing. The irony with which she represents the health and beauty industries does not go unnoticed. Defining herself as a collector, the artist presents us with all the objects in her collection, objects that usually come into direct contact with the skin or that allude explicitly to the body. Further to her criticism of the beauty industry, there is also a discourse around the human and the mechanical in her work. Two of the videos that form part of the exhibit reveal the process involved in the production of a brush, one of them handcrafted, the other made by machine.

Jeong defines her ‘Spa & Beauty’ performance as a 'demonstration', a little-used term in the art world, but very revealing in that it describes a performance that seeks to give us a close-up of work in a spa. It has, therefore, something of the theatrical about it in the way it makes us participate in a fiction and accept the 'illusion' of actually being in a spa. In that sense, it might be appropriate here to mention Baudrillard's notion of simulation to describe how the project alludes to a reality familiar to all of us but is in fact one born of simulation.

Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery

Geumhyung Jeong is an incredibly versatile artist, each of her projects broaching new themes as she implements different strategies of staging and interpretation. For instance, in her performance piece ‘7 Ways’ at the Tate in 2017, she dazzled with her skill at moving around the 'stage'. She interacted with objects from her collection but, on that occasion, not only did she create the illusion that she was moving the objects but also that they were the ones moving her. In her 2019 ‘RC Toy’ performance at the Kunsthalle in Basel, she created robots to which she attached body parts. The result was creatures, half-man-half-machine, with which she interacted in an overtly sexual way. The remote control activating each robot was located in the erogenous zones of the other robots so that they were all interconnected and activated by her presence in a kind of robotic orgy.

This is a groundbreaking debut from The Ryder Gallery which has just opened its doors in Madrid as part of an ambitious project involving over five years’ work at its headquarters in London.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Francisco Calvo Serraller

Let me start by highlighting what makes the 'Lorenzo Lotto. Portraits' exhibition such an exceptional project. Firstly, because never before has this subject been featured in a monographic exhibition; secondly, because this is the first ever time an exhibition of the great Venetian artist's work has been organised in Spain, which has only one of his paintings on display, here at the Prado; thirdly, because it comprises almost fifty works, some of them among his best; fourthly, because, although Lotto's main focus was, as the exhibit title would suggest, the genre at which he excelled ~ portraiture, a substantial complementary space has been added to showcase his uniquely personal and beautifully rendered religious painting; and finally, for its splendid presentation and staging at the reputable hands of Jesus Moreno. And as if all that were not enough, it is also worth mentioning with regards to the venue that this inauguration coincides with two other first-rate exhibitions, namely 'Rubens. Painter of Sketches' and 'In lapide depictum. Italian painting on stone 1530-1550", constituting a trio of internationally unmatchable calibre at the Prado.

|

Dr. Francisco Calvo Serraller, writing exclusively for Alejandra de Argos |

|

Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia (1530 - 1533). Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 110.6 cm. The National Gallery, London

Let me start by highlighting what makes the 'Lorenzo Lotto. Portraits' exhibition such an exceptional project. Firstly, because never before has this subject been featured in a monographic exhibition; secondly, because this is the first ever time an exhibition of the great Venetian artist's work has been organised in Spain, which has only one of his paintings on display, here at the Prado; thirdly, because it comprises almost fifty works, some of them among his best; fourthly, because, although Lotto's main focus was, as the exhibit title would suggest, the genre at which he excelled ~ portraiture, a substantial complementary space has been added to showcase his uniquely personal and beautifully rendered religious painting; and finally, for its splendid presentation and staging at the reputable hands of Jesus Moreno. And as if all that were not enough, it is also worth mentioning with regards to the venue that this inauguration coincides with two other first-rate exhibitions, namely 'Rubens. Painter of Sketches' and 'In lapide depictum. Italian painting on stone 1530-1550", constituting a trio of internationally unmatchable calibre at the Prado.

Portrait of Andrea Odoni (1527). The Royal Collection Trust, London

Moreover, Lorenzo Lotto's biography and subsequent destiny of critical acclaim are a constant source of interest. A native of Venice itself whose exact date of birth is unknown but is estimated by experts to be around 1580, our grand master's training and career start could not have been more brilliant, having as he did rolemodels such as Giovanni Bellini, of whom he was reputedly a direct disciple, along with Giorgione and Titian but he was also influenced by Antonello da Messina and Albrecht Durer, a manifestation of the great significance and variety in the configuration of his own particular style.

His early days as a professional in Venice were met with notable success and the promise of great things to come but the stiff competition with other local masters such as Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese, all of whom were endowed with a more pugnacious and business-minded temperament than his, left him with no other alternative than to seek his fortune outside the closeted enclave of the Republic's capital, in the comparatively minor cities of Veneto and neighbouring areas. In this way, Lotto managed to make ends meet with varying degrees of success and, as can often happen in the course of anyone's life, with the passage of time his star waned, only for him to end up as an oblate in Loreto, not knowing where else to live out his last days.

Portrait of a Young Man (1530 - 1532). Oil on canvas, 98 x 111 cm. Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

Then and now, the reality is that very few artists are able to make a living from their work alone and fewer still if we look back at the past because, until recently, neither were there many other options if luck wasn't on your side. In this sense, Lotto's own personal frustrations cannot be taken as exceptional and neither can the fact that at the time of his death he had not received the recognition he deserved. In actual fact, recognition of his memory and work had to wait until the 20th century when Berenson revised and raised the profile of the hitherto disdained painting of 15th century Italy but, ultimately, he didn't receive proper public acclaim until the latter stages of the 1900s. And in some ways, this widespread recognition of his oeuvre is very recent indeed, as demonstrated by this exhibition which, as previously mentioned, is only the first ever in Spain as well as being the first in the world to monographically showcase his portraiture, a genre to which Lotto made outstanding contributions. These are evidenced in the only painting of his owned by the Prado, a novelty at the time in Italy for depicting a newly-wed couple, as can be seen in the various heraldic elements. Obliged on this occasion to use a landscape format, Lotto continued to do so with individual portraits which gave the subject much greater spacial freedom and the possibility of encompassing a wider horizon. In any case, what is so extraordinary about the quality of Lotto's portraits is not limited just to their format. There is also an effect on composition, psychological aspects, his astute judgement as to the symbolic use of circumstantial details to identify the personality, rank and office of the sitter, the beautiful way he paints hands, among many others. Whatever the case, the result is that Lotto's portraits seem so modern that their impact is perhaps greater now than when they were painted because they give us the impression that their physiognomies and expressions are the same as ours. Whilst true that during the first half of the 16th century, at the height of Mannerism, this type of painting that we are so fond of today proliferated, and notwithstanding other brilliant portraitists of the time, Lotto stands out. There are a selection of his best and most well-known here at the exhibition, for instance Portrait of a Young man with a Lamp (c. 1506), Andrea Odoni (1527), Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia (c. 1530-33) and Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1530-32) but there are also others of equally high quality albeit not as popular as the aforementioned, from the very early Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1498-1500), still heavily influenced by Bellini but with eyes and mouth that show a profound psychological insight, up to and including Bishop Bernardo de Rossi (1505), Portrait of a Young Man (c.1512-13), Lucina Brembati (1520-23), Portrait of a Young Man with a Book (c.1525), Portrait of a Gentleman (1535?), Portrait of a Man with a Beard (c. 1540), Portrait of a Man with a Felt Hat (h. 1541) or Portrait of an Architect (c.1540-42), to mention but a few of many outstanding pieces.

Portrait of a Married Couple (1523 - 1524). Oil on canvas, 96 x 116 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

But in addition to this magnificent display of portraits, the exhibition also includes other genres in Lotto's repertoire and, in particular, his religious painting where delicate, stylised figures writhe in space as in a harmonious ballet, their body language dramatized in studiously-arranged twists and turns and the scene as a whole is wrapped in a chromatic sheen of glossy satin where colours contrast with each other in original and imaginative ways. This added bonus is an essential complement in a country like ours where the work of this Venetian painter is only being exhibited monographically for the very first time.

Lastly, and in another contribution to the ensemble, there are display cases containing various textile and gold or silver objects that don't just illustrate the dress and jewelery of those memorialised in the portraits but also explain their function within the narrative, thereby demonstrating that we are not just viewing a presentation of Lotto's paintings, but rather we are seeing an interpretation of them, and in many cases a novel one at that. It is interesting that, in this regard, the focus is on portraits where the subject is represented as an incarnation of the ideal of holiness, a burning issue at the precise moment in history when the ideological battle to control and censor images was at its peak.

The Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Anthony Abbot and Louis of Toulouse (1506). Oil on panel, 175 x 165 cm. Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, Asolo

This exhibition, which after its run at the Prado will move on to the National Gallery in London, has been curated by Enrico Maria dal Pozzolo y Miguel Falomir, in collaboration with Mathias Wivel. All of them deserve to be congratulated on their splendid work, along with the layout and arrangement of the pieces, not forgetting the beautiful and informative catalogue which, in this case, is an indispensable complement to the exhibition.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- The wonderful rediscovery of Lorenzo Lotto - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

This could be the beginning of a novel: Poseidonia, 5th century BC, and tragedy befalls a family from the local aristocracy. The lifeless body of their only child, a son initiated into Orphic rites, is returned to them from the Wars of Sybaris. The mother covers her son's eyes with Poseidonia's first roses in flower, their praises sung by Virgil for their perfume and twice-yearly blooms. The mother then lays her musician son's lyre, its soundbox a turtle shell, on his breast. As dawn breaks, the father leaves the city walls to commission the most opulent of burials for his son. He seeks out the most gifted painters, those able to create the most moving scenes ..... This article pertains to the story of a burial: an element as intrinsic to the human condition as our own mortality.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

2018 marked the fiftieth anniversary since the discovery of the enigmatic Tomb of the Diver. Now on display at the Museum of Paestum in Campania, its 37-year-old archaeologist director Gabriel Zuchtriegel - yet another German director of an Italian museum - curates the Autumn exhibitions celebrating this ephemeris.

*******

This could be the beginning of a novel: Poseidonia, 5th century BC, and tragedy befalls a family from the local aristocracy. The lifeless body of their only child, a son initiated into Orphic rites, is returned to them from the Wars of Sybaris. The mother covers her son's eyes with Poseidonia's first roses in flower, their praises sung by Virgil for their perfume and twice-yearly blooms. The mother then lays her musician son's lyre, its soundbox a turtle shell, on his breast. As dawn breaks, the father leaves the city walls to commission the most opulent of burials for his son. He seeks out the most gifted painters, those able to create the most moving scenes ..... This article pertains to the story of a burial: an element as intrinsic to the human condition as our own mortality.

A tomb was - then and possibly still now - a sacred place where, as believed among initiates in the Orphic mysteries, the transmutation of death into resurrection, the moment when the soul was liberated from the body, took place. And for that to occur, a perfect setting was required. This is why Egyptian tombs concentrated all their magnificence and all their condensed artistry on the inside. This is why perfection was sealed up and hidden away. And this was because there was a mystery contained within them.

In Ancient Greece, as a partaker in the mystery religions rather than in terms of its Olympian beliefs, the tomb also became a sacred place. They were a kind of magnificent time capsule, decorated almost to perfection, a little chamber that led to another state of being.

On 13th June 1968, the Italian archaeologist Mario Napoli is carrying out excavations at a small necropolis about a mile south of the city of Paestum - the Ancient Greek city of Poseidonia - on the Gulf of Salerno in Southern Italy. As evening falls, he starts work on a fourth tomb that, when finally dug free from the earth, looks surprisingly intact. With the sun setting, the box is opened and, after 2,500 years of darkness, light floods the interior of the tomb once more, bringing some astounding paintings back to life.

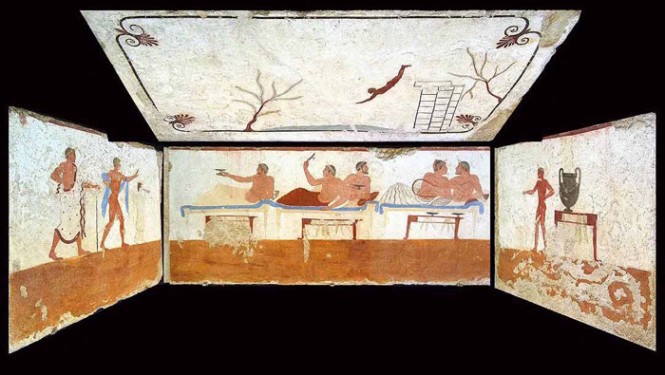

Slabs from The Tomb of the Diver, in their original positions

The four sides and cover of the sepulchre consist of five slabs of local limestone, while the base is dug into the ground. The slabs are neatly bonded together and form a chamber about the size of an adult male. All of the slabs are painted using the 'true fresco' technique but the fact that the one forming the ceiling is also painted is somewhat unusual. Mario Napoli sees for the first time the scene that will ultimately give the tomb its name: a young man diving towards the curling waves in the waters below. The Tomb of the Diver has just been discovered, the only extant example of Greek painting with figurative scenes from the Orientalizing, Archaic or Classical periods to survive wholly intact. Among the thousands of Greek tombs known of at this time (700 - 400 BC), this is the only one decorated with frescoes depicting humans. It is, in this sense, a revolutionary one. The great paintings of Zeuxis, Apelles and Parrhasius have only come to us through narrative tradition and historians but we have never seen them. They exist only in fragmentary form and, of course, in the richness of the amphorae.

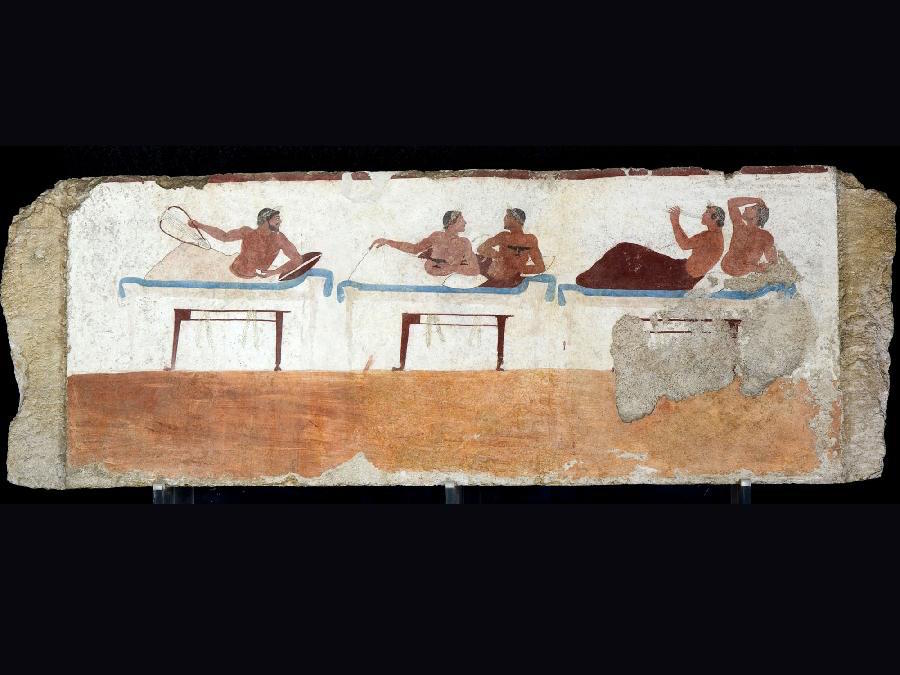

Inside the grave and near the body - probably that of a young man - are two objects: the shell of a turtle, once the soundboard of a lyre whose wooden casing had long since rotted away and an Attic lekythos vase in black-figure technique, as used around 480 BC, which helped to date the year of the tomb to around 470 BC. The lateral frescos surrounding the body depict symposium scenes of a traditional Ancient Greek banquet: bare-chested young men wearing laurel garlands reclining on sofas, partying, dancing, drinking wine, playing lyres and games and being in love.

The Tomb of the Diver. North Wall (banquet scene detail)

However, it is the ceiling slab, the one facing the gaze of the dead man, that has been the still-unresolved focus of much contentious interpretation. It is this segment that encapsulates the mystery and the rivers of ink written in archaeological research: a scene bordered by a black ribbon with palmettes in each of its four corners. In the centre, a naked man suspended in the air, diving into the river below. On the right are three stone pillars, presumably his diving board, and on either side are the bare outlines of two trees. And then, nothing. Just the white background, nothing else.

The Tomb of the Diver. Ceiling slab.

In Ancient Greece, neither swimming nor diving were activities the elite indulged in. The swimmer depicted in this tomb, isolated against the sky, symbolizes - the jury is still out on all the hypotheses - the intensity of the moment of death. This man and his leap are the visual metaphor for the transition to eternity from earthly life.

At that time, Greece was living the tradition of its Olympian beliefs, with its bored, mountain-dwelling gods, impervious to earthly needs toying with, for pure entertainment, and torturing mere mortals. For them, the vision of life after death was extremely pessimistic. Without exception, without differentiation, without judgement on the righteousness of their previous life, the souls of all mortals were condemned to Hades, a dismal place where they eked out a miserable existence envying the living.

However, around the time The Tomb of the Diver was constructed, for those living in Magna Graecian cities, new ideas from other Eastern belief systems would come and go in their everyday lives as if by capillary action: the mystic or Orphic cults, for instance, whose occult rites were based on the hope for some kind of life after death. As Pythagoreanism and Orphism spread, only those who had been initiated through a series of secret rituals could aspire to these other-worldly hopes.

And it is precisely this aspect that makes our tomb so special: the metaphysical message it communicates through visual language. Because it is the case of The Tomb of the Diver that the paintings seem to be portraying the central ritual of initiatic, religious practices entailing a banquet in which, through orgiastic stimuli, a state of exaltation and mystical fervour is invoked in the participants. This state recalls the passion of the God Dionysus and his presence inside an animal that was ripped to shreds, its flesh and blood consumed by Titans in a ceremonial banquet. The intense fervency attained enabled participants to feel the force of the soul within the body and this anticipated the experiencing of its liberation from the body which could only happen after death, once the soul had finally departed the body.

Incidentally, this idea of life after death was being propagated in Greece a full five centuries before the birth of Jesus Christ in Bethlehem, Judea. We have here an early precedent for Christianity that would seem to be its replica projected backwards.

It is believed that our young man, who died long before his time, would have been an initiate of these rites. In his tomb, the image of death as a rapid passage through water would remain forever above him. And his body would be surrounded by scenes from a banquet that would never end and in which he would participate for all eternity, playing his lyre with his musician friends.

But who was the young man buried there? What kind of life had he led? How did his parents commission his tomb? What of the two artists who painted it? What did they do with their son's body on the days when the tomb's walls were being cut out of rock, plastered, dried out, chiselled to outline the drawings and then filled in with vivid colours? And again, why paint a magnificent tomb to be seen at the precise moment of burial only to seal it up immediately, never to be seen again?

An invisible image

An invisible image is a challenge. What happens when an image, painted 2,500 years ago never to be seen again, bursts onto our contemporary, traditional, cultural landscape where being comprehensible is the equivalent of being visible?

One thinks of other images in art history with encrypted messages, from Malevich's Black Square or the mysterious Romanesque frescos of San Baudelio de Berlanga to the prehistoric Altamira Cave bison and the inscriptions on the earliest Christian catacombs and Banksy.

Perhaps what's puzzling about The Tomb of the Diver is not so much the impossibility of deciphering its meaning but rather our attempts at coming to terms with the powerfulness of an image's intrinsic ambiguity.

The temples of Paestum and The Tomb of the Diver

On this October day, the grassy area surrounding the temples of Paestum is empty of visitors and full of autumn roses. The three Doric temples appear erect and severe in their golden Campania stone, about 90 kms from Naples and the shade of Vesuvius. The Temple of Neptune (460 BC), thus called but wrongly attributed to Poseidonia's protective divinity, is, for many scholars, the best preserved temple in Greek civilization. It is not easy to describe the powerful impact of seeing its facade, devoid of any decoration whatsoever, not even holes in the stone that might have allowed us to imagine there once being a statue clamped into its tympanum, nothing resembling the Pantheon or Phidias's statues of gods, horses, warriors, ..... This temple was conceived of to be bare and stern, even in its triglyphs and the metopes between. No goddesses on horseback. The tension is achieved solely by its monumentality, by the magic of its proportions, by its second row of intact columns, with its fluted pillars high as a forest and its orientation towards the East.

The Temple of Neptune. Paestum

In the 8th century BC, the Greeks were sailing the Tyrrhenean Sea around the mining regions of the Etrurian coast to buy metal. They settled near Ischia and so began their campaign of colonisation. Around 600 BC, sailors from the city of Sibaris founded the colony of Poseidonia, making it one of the northernmost extremes of Magna Graecia. It was then conquered by the Lucanians and finally, in 273 BC, fell under Roman rule and was renamed Paestum. The discovery of Paestum came in 1752 when King Charles VII (the future Charles III of Spain) ordered the construction of a road which would cut across the city. From then on, European intellectuals doing the Grand Tour, amazed by how well-preserved the temples were, made it their reference point for classical architecture until Athens was added to the European cultural itinerary. It was specifically in Paestum that Greek architecture achieved supremacy over the Roman and where the Greeks regained their "tyranny" over Europeans enamoured with their monuments. Winckelmann (1758), Piranesi (1777), Goethe (1787), John Soane (1779) and almost all the great architects of the time came here to see, study and measure the purest of all Doric temples. In 1758, the architect commissioned to build the Pantheon in Paris, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, found inspiration in the temples of Paestum, making the Neoclassical style so popular in France it would end up replacing the Barroque.

National Archeological Museum of Paestum

Vía Magna Graecia, 918

Paestum

Italy

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Una imagen invisible: la tumba del nadador - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

My flight touched down in Marseille on a sunny September morning and although my ultimate destination was Barjac, I couldn't help but make a small detour to visit the Château La Coste vineyards, a magical symbiosis of architecture, sculpture and natural landscape in the south of France. The complex's curator Daniel Kennedy was waiting there to show me the collection. The Tadao Ando Art Centre is a building conceived with the artist's signature elements in mind: smooth concrete, lines that are simple, modern and in tune with the vestiges of Japanese tradition, water, the dominance of light and an architectural design in perfect harmony with its surroundings. Then there's the magnificent outdoor collection comprising projects by the likes of Louise Bourgeois, Richard Serra, Tracey Emin, Frank Ghery, Jean Nouvel and Jenny Holzer to name but a few, dotted all over the landscape.

Author: Elena Cué

La Ribaute. Barjac. Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Elena Cué

My flight touched down in Marseille on a sunny September morning and although my ultimate destination was Barjac, I couldn't help but make a small detour to visit the Château La Coste vineyards, a magical symbiosis of architecture, sculpture and natural landscape in the south of France. The complex's curator Daniel Kennedy was waiting there to show me the collection. The Tadao Ando Art Centre is a building conceived with the artist's signature elements in mind: smooth concrete, lines that are simple, modern and in tune with the vestiges of Japanese tradition, water, the dominance of light and an architectural design in perfect harmony with its surroundings. Then there's the magnificent outdoor collection comprising projects by the likes of Louise Bourgeois, Richard Serra, Tracey Emin, Frank Ghery, Jean Nouvel and Jenny Holzer to name but a few, dotted all over the landscape.

Maman. Louise Bourgeois. Château la Coste. Photo Elena Cué

But that's not why I came to Provence. The whole point of my trip was La Ribaute so I quickly made tracks for Barjac, my goal. And what or who was it about this little town that had attracted me there? Well, none other than a certain Teuton, his legend and his very personal cosmology. This is a 200 acre estate containing over 60 massive barns, pavilions and greenhouses brimming with Anselm Kiefer's work all inter-connected via subterranean tunnels with caves, grottos, bridges, crypts and an amphitheatre. He has planted trees and vegetation, he has built trails, walls and fences. The La Ribaute project was begun and developed from the abstract idea of a vacuum. A vacuum that had to be filled.

Anselm Kiefer moved to Barjac in 1992 where he found, albeit with some reservations, the ideal space to build his own personal creative paradise. On one of the esplanades in these 40 hectare grounds stands a crown of his iconic and enigmatic towers: "The Seven Heavenly Palaces" that reference the mystic, Hebrew narrative of our celestial ascension by means of the gradual loss of our material bodies and spiritual elevation until we reach the final palace where only our souls remain forever. These apocalyptic towers symbolise the notion of creation and destruction that so characterises the work of the artist, who tells me: "I destroy whatever I make all the time. Then I store the broken bits in containers and wait for their resurrection."

The Seven Heavenly Palaces. Photo: Charles Duprat. (c) Anselm Kiefer

This amazing artistic complex has hardly ever been visited, not yet being open to the public, and my tour of it was a succession of unique sensations, beginning at dusk as I made my way to the old silk factory where Anselm Kiefer and his trusty assistant Waltreaud were waiting for me. His face tanned, his eyes lively and intense, his smile inviting me to embark on our visit, we set off for the nearby buildings. We walked along paths lined with flora typical of the region and along which were placed sculptures of his characteristic lead books, symbolic of knowledge, strewn over or piled up on large blocks of stone, almost as if at any moment a sorcerer might emerge from the depths of the forest in some feat of alchemy.

Anselm Kiefer. Barjac. Photo: Elena Cué

What first impacts me is a greenhouse topped with a World War II-like airplane made of lead with dried sunflowers spouting from it. Kiefer cultivates them here from Japanse seeds that grow to seven metres high. As if in a laboratory, he also cultivates tulips and other plants he will later use as materials for his work. These spaces devoted exclusively to one piece are the ones that resonate the most. We continue on to the next pavilions housing installations, paintings and sculptures all with the Holocaust as their theme. Kiefer's childhood was marked by a silence around what had happened: "When I was young, the Holocaust didn't exist. Nobody spoke about it in the 60's." He could feel there was something missing, something hidden and when he found out what it was, Kiefer tells me: "I was so affected by Hitler I started studying the Holocaust. I wanted to know what it was all about. What happened at that time is so horrible it's hard to imagine it." This would become a vital theme in his work.

In 1945, in the Black Forest, in the city of Donaueschingen where the two sources of the river Danube converge, Anselm Kiefer, one of the most prominant artists of our time, was born into a devastated Germany. While his mother was giving birth in the basement of a hospital, the family home was being blown to pieces by Allied bombs. The son of a Wehrmacht official, his childhood was marked by the authoritarianism of his father and a strict Catholic education.

Growing up in the ruins of a Germany that was destroyed and anxious to erase its tragic past awakened a profound interest in Kiefer to get to know about Judaism and the event that embodied archetypal evil - the genocide committed by Nazis. That catastrophe, so infinite, so boundless in its terror, so impossible to imagine let alone depict was to become the central strand in Kiefer's aesthetic and ethics.

Barely an hour later, I returned to the main house. In a huge, white, rectangular room of grandiose dimensions, the emptiness was only filled by one white linen sofa, some curtains hiding a bed at one end and an industrial kitchen with a large table of rustic wood at the other. I immediately joined the others for a supper that went on for five hours. Kiefer talked about the sensation he gets on seeing his paintings in retrospect, namely, a certain perception of his work as never being finished. As an aside, he mentioned how difficult it was to transport his "The Morgenthau Plan" from La Ribaute. This installation, housed in one of the pavilions, is the metaphorical conceptualization of the proposal masterminded shortly before the end of WWII by the US Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau. The plan consisted of the elimination of Germany's industries and its subsequent transformation into an agricultural country. In it, Kiefer explores that would-be rural landscape: the resurgence of flowers from the devastation before. He considered it to be pure propaganda: "You know, all they did was help Hitler with this plan. They calculated that between 10 and 15 million Germans would die of hunger. And Roosevelt didn't want this. Hitler listened to Goebbels and, as far as they were concerned, it was a godsend; they would have the perfect excuse to maintain the German state by warning its citizens about what would happen if they didn't fight on. Not long ago, I also saw something about the Marshall Plan and that was all propaganda, too. Did you know that?"

The Morgenthau Plan. Barjac. Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat. (c) Anselm Kiefer

The conversation went on so long that it got very late and I was invited to stay the night. The room, as with the rest of the building, was huge and somewhat intimidating as much for its dimensions as for the austerity of its minimalist decor. The following morning, we went to have a look at a series of the catacombs that are connected to each other like the creeping roots of a rhizome and to the pavilions above them at ground level. Before going underground, we went into the amphitheatre, which is the centrepiece of La Ribaute, as the artist was telling me: "The amphitheatre came about the same way a painting would. I had a large wall where I hung all my large paintings and I just thought, why not make a little grotto inside? So, I got hold of some containers and covered them with liquid cement and put them all together. The aim was just to have a little alcove in that big wall. Then, we continued with another layer on top, and another, etc and it kept on working out like a drawing. I've no idea how it will end up ...". This construction, 15 metres high, consists of different installations in each of the rooms within the containers. In one of them, there are reels of film, made out of strips of lead, hanging from the ceiling and featuring photographs taken by the artist thirty years ago.

Amphitheatre. Barjac. Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat. (c) Anselm Kiefer

From there, we took an underground route that was somewhat reminiscent of a stone Gruyère cheese and I was immediately stopped in my tracks. Accessed by a narrow cave, we had come face to face with a deeply disturbing room, its walls lined with lead, the floor deep in water and a single light bulb hanging from a cable attached to the ceiling. Kiefer told me this was the first ever room he had completed and asked me, out of curiosity, what I thought of the acoustics. I answered that I hadn't experienced any sound at all. I'd been stunned into silence by what I saw.

Lead Room. Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat. (c) Anselm Kiefer

As we make our way through the grottos, our perceptions change continually, the artist disappears and we are transported to other times, other places. Through these subterranean passages, we are able to travel to the Palaeolithic age, to the tragedies of Ancient Greece, to the time of Christ and to Auschwitz. And so we arrive at another impactful room: "The Women of the Revolution", sixteen beds with puddles of stagnant water on their rumpled, lead sheets giving the impression of skin or leather. This was the dividing line between the female interior and exterior that the artist uses as a metaphor for the immense inner power of women faced with the bravado of men. The highlight of the room is on the wall opposite - a lead panel picturing Kiefer with his back to us, in a landscape that very much reminded me of the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer Above A Sea Of Fog". It brought to mind the Kantian concept of the sublime and the inability of our imagination to grasp something so inestimable and so totally exceptional.

The Women Of The Revolution. Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat. (c) Anselm Kiefer

The tour over, I returned, even more staggered by the experience than before, to the main house to interview Kiefer. We talked at length over lunch during which time I discovered Kiefer's interest in science. He spoke with great admiration of the Spanish scientist Luis Alvarez-Gaume and his light particle teleportations to distances of tens of thousands of kilometres. "It's called teleportation. It happened to me and my grandmother. We used to think the exact same thoughts at the exact same time."

And we remembered Kant: "Every mention of the sublime has within it more enchantment than the phantasmagoric charms of the beautiful."

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- In the grotto of the Teuton. Anselm Kiefer in Barjac - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

2019: The Year of Rembrandt. Amsterdam kicks off Holland's 350th anniversary celebrations for the Old Master with its exhibition "All The Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum" which will then make its way to Madrid's Prado as "Vélazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer ~ Artistic Likenesses from the Spanish and Dutch schools". One would be forgiven for thinking the central gallery of the Rijksmuseum was less than sixty metres long because, on opening its panelled doors of leaded glass, our eyes are immediately drawn to the illuminated hand held out towards us by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. It beckons us from that distance away, making us want to step into the canvas with him as he gives the order for his company to begin their night watch through the streets of Amsterdam.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

2019: The Year of Rembrandt

Amsterdam kicks off Holland's 350th anniversary celebrations for the Old Master with its exhibition "All The Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum" which will then make its way to Madrid's Prado as "Vélazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer ~ Artistic Likenesses from the Spanish and Dutch schools".

One would be forgiven for thinking the central gallery of the Rijksmuseum was less than sixty metres long because, on opening its panelled doors of leaded glass, our eyes are immediately drawn to the illuminated hand held out towards us by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. It beckons us from that distance away, making us want to step into the canvas with him as he gives the order for his company to begin their night watch through the streets of Amsterdam.

The central gallery of this neo-Gothic museum somewhat resembles the stem of a basil plant, with its lateral chapels branching off either side of the central aisle and housing the world's largest collection of Dutch Golden Age paintings. The visitor is thus forced to zig-zag between them while, at the very end, in the apse, as if an alterpiece, hangs Rembrandt's "The Night Watch", his controversial, secular, colossal painting of 1642.

From the very start of this visit, we are already getting a sense of something quite different from the mythological, religious and military scenes usually found in other collections of 17th century Dutch, Spanish and Italian paintings. Where are the heavens opening to reveal the glory of God, the Depositions of Christ, the Flights from Egypt or the Epiphanies? Where are Apollo and Daphne, Danae, Proserpine?

Even before arriving at the Rembrandt gallery, several other pictures, oddly small in format, showcase another style of painting. Theirs saw the establishment of a brand-new genre of painting, one that is striking not just for its relentless verism but also for its never-before-seen themes. Domestic scenes portraying an urban, bourgeois life and families inside their homes of oak furnishings, Delft tiles and kitchens bathed in light. And their world of scenarios that are essentially feminine and intimate in nature ~ women standing alone, reading a letter or playing the harpsichord, cradling a baby, sweeping a room or putting on a pearl necklace, their faces lit by daylight from an open window. Scenes that almost seem to be happening on a lazy day off.

Vermeer, Woman Reading A Letter (1663-64), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Staggering numbers

There has been, perhaps, no other country ever where so many paintings have been produced in such a short period of time. It is estimated that between 1600 and 1700, up to 10 million paintings were produced in the Netherlands. Between 1650 and 1675, both Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) were active as well as at least half a dozen other top-notch painters such as Carel Fabritius, Gerard Dou, Gerard ter Borch, Frans Van Mieris, Jan Steen, Pieter de Hooch and Gabriël Metsu.

What made such prolific artistic production possible? What led the United Provinces to write a fundamental chapter in the history of art? An art which, incidentally, was at once so very localised yet so eternal?

From a technical point of view, the theorist Karel van Mander, echoing Giorgio Vasari, confirms that Golden Age Dutch painting derived from 15th century Flemish painting, from the preciosity of Jan van Eyck's, Robert Campin's and Roger van der Weyden's paintings, still under the guise of religious scenes but also depicting the interior of contemporary homes, their fireplaces, chancellors' bibles, saints' clogs, the damask and fur of their garments and the lilies of archangels.

The artists' lives were, coincidentally, punctuated by highly dramatic, military and political events that did not, however, seem to have left any mark on their work. The 17th century was one of the bloodiest in history, its wars notorious for their long duration. The Netherlands, divided by Civil War into Calvinists and Catholics, fought the Spanish Crown in the same way it fought the sea which inundated its plains time and time again, filling its landscapes with windmills, dykes, canals and bridges. They were Master Naval engineers whose fleets managed to achieve dominance over most of the world's commerce. Until the 1640's, the Dutch empire extended from Brazil to Africa and from Indonesia or Japan to the east coast of North America, establishing its capital there as New Amsterdam, now known as Manhattan.

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded, its 160 ships sailing the oceans transporting and unloading extraordinary cargo ~ tonnes of blue and white Chinese porcelain, wood and grain from the Baltics, Persian rugs, sugar from Brazil, fruit from the West Indies, spices and pepper from Java, Sumatra and Borneo. Turkish sultans sent tulips and with them came 'tulipmania' which, in the 1620's, almost caused riots due to a price rise. A few absurd sales receipts still exist ~ luxury mansions paid out in exchange for a single bulb. It was the first speculation bubble in history.

Amsterdam and its port thus became the greatest trade centre in the north of Europe. A Stock Exchange was established there and is considered, after that of Antwerp in 1460, the oldest in the world. Founded in 1602 by the VOC, and the first to function like the modern stock market, its aim was to create funding for future commercial shipping.

This global trade network created an elite clientele with abundant amounts of money with which to adorn their houses. The decorative arts flourished, as did the quest for luxury items and, above all, paintings which were to become the new status symbols. Gone the patronage of aristocracy and Church, it would be the bourgeoisie from now on paying the piper and calling the tune on the subject matter to be painted. And they wanted to see a reflection of their own lives, their hardships and dreams in those paintings. They wanted to feel recognised. Dutch art, artists, buyers and dealers were the catalyst for the future international art market, such as we know it today.

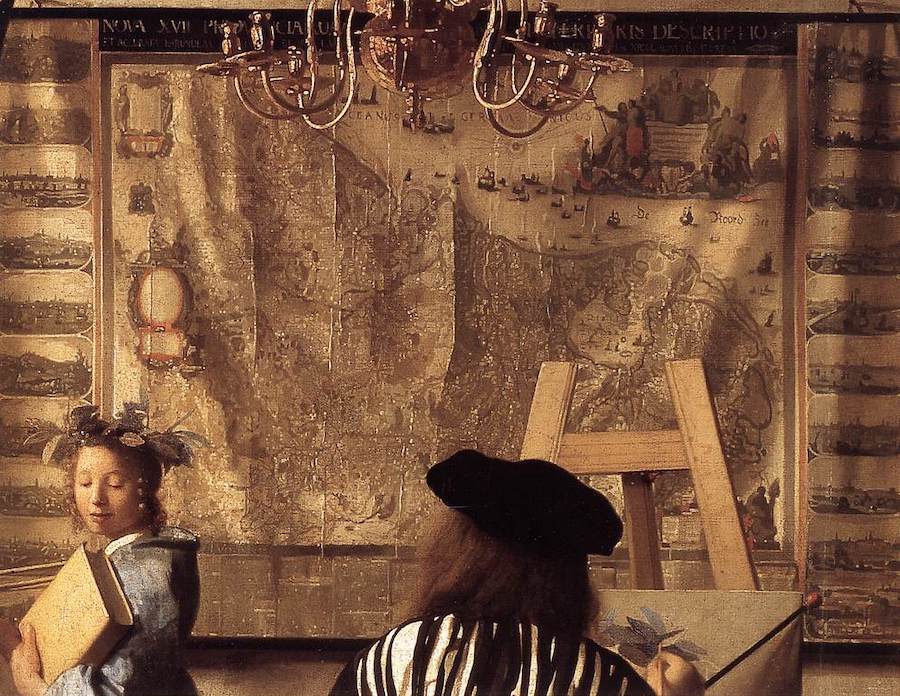

Vermeer, The Art Of Painting (1666), detail showing a map of the United Provinces, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Leapfrogs and bounds

This is script being written and informing our progress through the galleries, providing context and background against which Vermeer in Delft and Rembrandt in Amsterdam showcase their own particular way of painting. In the case of Vermeer, it would appear to be a natural progression from the mentality of his time. For Rembrandt, it was a giant leap forward.

On a wall near "The Night Watch" hang three tiny paintings that signal, from the outset, an ethereal calm in space and time. These are all three Vermeer paintings owned by the Rijksmuseum. "The Little Street" (1658) measures little more than fifty centimetres and is so lifelike it appears not to exist at all. It is as if there were a hole in the museum wall through which a real street scene in Delft can be glimpsed. Perhaps for this reason, it is said of Vermeer's art that it predates the realism of photography, the only artform to, centuries later, attempt to portray the very air surrounding figures in this way.

Vermeer, The Little Street (1658), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"The Milkmaid" (1659) is dressed in Vermeer's favourite colours of yellow and ultramarine, intently pouring a fine stream of milk into a clay bowl. She looks as if she is not to be disturbed. The still life on the table with its crusty bread and specks of sunlight, the wicker basket and, most noticeably, the wall behind her bathed in light creating a shadow under the nail, the different colourations of whites marking a stain or, as in the corner, the ochre variations of damp combine to form an intense reality, small but perfectly-formed, vast and magical. The precision of tone is remarkable. An artist must, in short, have the gift of seeing everyday things in a different way to us. Creativity has to entail something like how to illuminate these ordinary things with a brighter light, with more concentrated attention, with a distinctly powerful charge. When Rembrandt paints a glass of wine, it ceases to retain its natural state of being a glass of wine and becomes, rather, part of an action. He beams theatrical light onto it, he sets it on a stage. Vermeer, on the other hand, isolates it, wanting a light just for this one glass, he grants it the virtue of being itself, unique, material and independent, in a moment of time that is motionless. Vermeer paints the time that flies between things.

Vermeer, The Milkmaid (1659), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the years when Rembrandt and Vermeer were active, the world was engaged in a scientific revolution. New ideas were being touted about what it meant to 'see'. People had started to believe Nature was hiding a world invisible to the naked eye and that science should focus on researching it and finding out. There was a wave of empirical thought needing to back itself up with instruments able to measure Nature and allow us to see parts of the world that had been hitherto invisible. Hence, the 17th century saw the invention of the thermometer, the barometer, the telescope and the microscope. And its painters, determined to discover Nature and to paint it using an array of optical effects, went back to relying heavily on lenses and camara obscura devices. We do not know whether Vermeer used such techniques in his painting or not but what is certain is that he was familiar with the effects they produced and how light influenced how we see the world. He reproduced how it accentuates colour tonalities until they appear jewel-like, how it blurs or sharpens the outlines of figures, how it highlights where the touches of light brighten and polish whichever reflective surface the sun falls on.

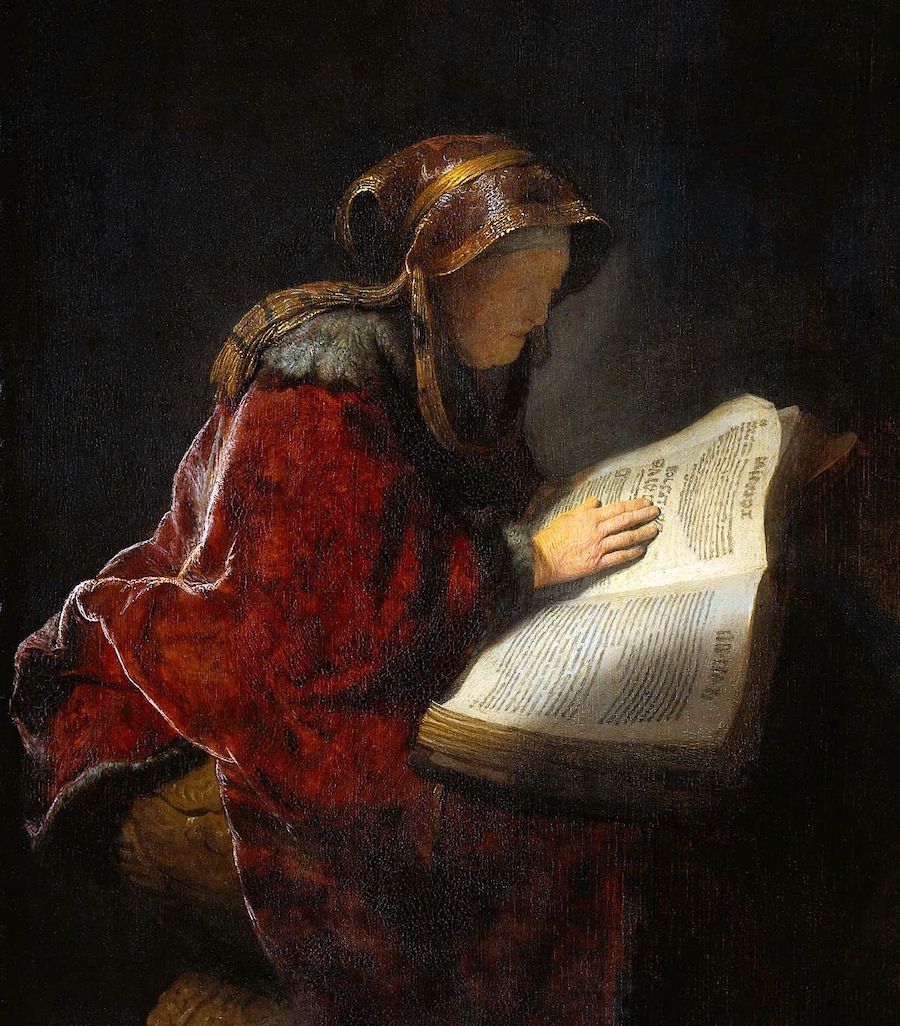

Vermeer painted "The Milkmaid" some 16 years after Rembrandt started work on "The Night Watch". Both paintings were a pictorial revolution but they were poles apart. To simplify Svetlana Alpers' study of 17th century Dutch painting, one might say that Vermeer represents the pinnacle of descriptive painting and its debt to observation whilst Rembrandt uses narration and historical themes as a pretext for injecting a certain wildness into his painting as the key to expression, action, gesture and the innermost recesses of the soul. His studies of light and matter are merely a means by which to paint the depths of pain, loneliness, failure, power, blindness or life just before death.

Rembrandt, The Prophetess Anna (Rembrandt's Mother) (1631), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Ten years, ten days

In a documentary about the last years of Rembrandt's life, Simon Schama describes a scene. It is 1885 and a young artist visiting the Rijksmuseum stops dead before a painting, his eyes transfixed, breaking into a feverish sweat as he gazes at the adored work. "I would give ten years of my life if I could simply sit and meditate, with a dry crust of bread, for ten days looking at it." So what was it about "The Jewish Bride" that so mesmerised the young Van Gogh? Days later, he would write that Rembrandt had painted it with "a hand of fire". Schama interprets the impact on Van Gogh as that of any masterpiece ~ it takes aim directly and viscerally. Van Gogh was another painter who took brushstrokes to their most physical extreme and this final work of Rembrandt's left him spellbound. In it, the Old Master, by now penniless and at death's door, depicts the physical incarnation of love. Its whole meaning is that of touch and caress. "The Jewish Bride" is a symphony of four hands, those of a couple. A man's hand on his wife's heart, the woman's hand touching this hand, a man's hand protectively around his wife's shoulder ...

Rembrandt rushes this final painting with the rage of his materials. The sleeve he paints here is not easily explained and one would need to be standing, as Van Gogh did, right in front of it. The sleeve is a physical crust in dozens of shades of gold, a mass of pictorial density that has a whole world of matter embedded in it: pieces of egg shell, crushed glass, mud, silica, ... The Old Master is acting on the painting the way the likes of Pollock, Freud and Kiefer would act on theirs centuries later ~ painting emotions with their materials.

Rembrandt, The Jewish Bride (1662), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"The Jewish Bride" features in the exhibition, as does "The Night Watch" with its outstretched hand, along with the whole astounding collection - the world's largest - of Rembrandt's canvases, drawings and etchings owned by the museum. Nevertheless, what makes this exhibit unique is something else. It is, essentially, about finding oneself in the presence, just a few feet apart, of two genius but contrasting artists. In and out of Rembrandt, on to Vermeer, retrace our steps back to Rembrandt and ..... start all over again. As Simon Schama said about them: Vermeer versus Rembrandt ~ crystallization versus emotion.

Rembrandt, The Night Watch (1642), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

All the Rembrandts at the Rijksmuseum

Rijksmuseum

1070 DN Amsterdam

Curator: Jonathan Bikker

15 February ~ 10 June 2019

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

The ending of Paolo Sorrentino's film The Great Beauty is one long, slow take over the River Tiber. The aerial camera rolls, at bird's eye height, from one bank to the other, flying over couples out for a summer stroll, or sometimes at one with the channel of water, crossing through the dark eyes underneath bridges or resting on streetlamps lit for a Roman sunrise. The very last scene in this serene finale takes us up close to the Sant’Angelo Bridge. Before the screen fades to black, Sorrentino abandons us on one of the angels that Bernini ideated to decorate this bridge connecting the Vatican with the Tiber. And from there, we call to mind what this city of popes, this epicentre of the 17th century world means for us as we marvel at the works of a unique man with the Eternal City always on his mind.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

The Rape Of Proserpina (detail), 1621-22, Borghese Gallery, Rome

The ending of Paolo Sorrentino's film The Great Beauty is one long, slow take over the River Tiber. The aerial camera rolls, at bird's eye height, from one bank to the other, flying over couples out for a summer stroll, or sometimes at one with the channel of water, crossing through the dark eyes underneath bridges or resting on streetlamps lit for a Roman sunrise. The very last scene in this serene finale takes us up close to the Sant’Angelo Bridge. Before the screen fades to black, Sorrentino abandons us on one of the angels that Bernini ideated to decorate this bridge connecting the Vatican with the Tiber. And from there, we call to mind what this city of popes, this epicentre of the 17th century world means for us as we marvel at the works of a unique man with the Eternal City always on his mind.

Sant’Angelo Bridge, Rome

Rome is currently celebrating the 20th anniversary of the re-opening of the Borghese Gallery with an exhibition dedicated to Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), the last of the great, universal masters who made Italy the artistic heart of Europe for over 300 years. Not only was he the greatest sculptor of the 17th century, he was also an arquitect, painter, dramatic author, and, above all, the director general of papal Rome, a Rome that would be required to endure until the present day and to remain the most grandiose show of urbanism ever attempted. Bernini served under eight popes in this most Baroque of cities, a style that grew out of the triumphal catholicism of the Counter-Reformation. By 1600, Italy had already gone through many uneventful centuries when suddenly, in the space of a hundred years, it becomes more active than ever before. But why and how does Italy embody such artistic genius in its most absolute form time and time again? What is the mystery surrounding this small Mediterranean peninsula located between Spain and Turkey? What is its secret recipe for churning out artists of calibre from Giotto to Modigliani? What is the link between politics, the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation?

Let's take a closer look at the ten angels sculpted by Bernini between 1668 and 1669 when his entire oeuvre was dedicated exclusively to works that were full of emotion. The windswept Sant'Angelo Bridge angels are disconsolate between the clouds above and the solid, cylindrical Sant'Angelo Castle, with a black angel at its pinnacle, as a backdrop. In his latter years, Bernini, more than ever before, used the movement of robes such as theirs as a language with which to convey feeling.

The Sant’Angelo Bridge was built to connect the two banks of the River Tiber in the 1st century AD. In the Middle Ages, it gave access to the Vatican City. Since the 17th century, Bernini's sculptures have left the pilgrims crossing it open-mouthed with wonder. It is a matchless means of approach into the oval arms and colonnades of St Peter's Square, the bronze Baldechin ceiling, the spiritually-awakening Roman centurian Saint Longinus who had speared the crucified Jesus, the Throne of St Peter symbolic of the new Ecclesia Triumphans (Church Triumphant) and so on.

St Peter's Basilica and Square, Vatican City, Rome

In the 17th century, the power of Rome and its popes was unbounded. The Catholic Church, despite having lost some of its territories, gained a renewed sense of triumph after saving itself and its dogma from herecy. The new popes converted their desire for power into a spiritual empire, believing themselves the heirs of Roman emperors. St Peter's was their work and Bernini their right-hand master artist for 57 uninterrupted years. When our young sculptor, not yet 30 years of age, received and accepted Pope Urban VIII's commission to complete St Peter's, it was a challenge and a feat that, one could say, surpassed that of replacing the Twin Towers in New York after 9/11.

David (detail), 1623-24, Borghese Gallery, Rome

Bernini at the Borghese Gallery

Adding to Cardinal Scipione Borghese's already unrivalled collection, his eponymous gallery, set amongst gardens, lemon trees and fountains between Popolo Square and Mount Pinzio, is currently exhibiting almost all the paintings ever attributed to Bernini. Also on display and facing each other are his two bronze Crucifixions which are both normally housed outside Italy, one in Madrid's Escorial Palace and the other in Toronto. But, more especially, there are his greatest busts ~ the first and second versions of Scipione Borghese and that of Constanza Bonarelli.

Bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, 1632, Borghese Gallery, Rome

Bernini brought about a total transformation in the sculpted portrait, taking it out of Renaissance immortality and breathing new life back into it. He was a prodigious craftsman who learnt the trade from his sculptor father. He never attended school, never studied Latin and, since childhood, had escaped from his chores and work in Santa Maria Maggiore to what was his one true place of learning ~ the Vatican Museums. There, he would study works such as the Belvedere Torso or the Apollo and draw out his first sketches. However, in addition to his talent as a draughtsman and his technical mastery, Bernini's head also harboured the "concetto", the idea or the concept. It did not matter whether it was for an opera set or a village square. One of the "concetti" that obsessed him was to challenge his materials and make them exceed their limitations. To work at the whiteness of the marble until it appeared coloured. To invent unruly manes of hair speckled with shadows or deep beards like foam on the ocean waves, trepanning and chiselling away at his pale materials, the hands of Gods sinking into the flesh of a nymph or tears running down a cheek ... in such a way that he aspired to imbue cold, inert stone with movement and life.

Apollo and Daphne (detail), 1622-25, Borghese Gallery, Rome

Letting the city yield its mysteries

In Alejo Carpentier's preface to Love For the City, he writes: “To roam a city is to retrace it, deconstruct it and look at it until it yields up its mysteries." This exhibition also offers us an exciting second dimension whereby we discover Bernini's signature stamp throughout the rest of Rome via the ecstasies of his sculpted saints in church chapels, in the bronze stolen from the facade of the Pantheon to construct the Baldequin ceiling, in the heraldic bees from the Barberini family's coat of arms that embellish gods of mythology and funeral monuments alike, in his fountains with naked Neptunes stepping out of shells or his elephants carrying obelisks ....

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Cornaro Chapel, Santa María della Vittoria Church, Rome

And finally, in the Piazza Navona, still as it ever was today, is the palatial home where Cardinal Giambattista Pamphili was living in 1644 when he was elected Pope Innocent X. There was much commentary at the time about his wish not to move into the Vatican, a remote place on the opposite banks of the Tiber that horrified him with its identikit salons and sacred museums. He wanted to stay here in Rome proper, in this square that had welcomed carriages and horses and the whole Roman spectacle for 16 centuries. The Piazza Navona rose out of the Circus Agonalis, Domitian's stadium built in AD 85 and changed name from Agone, to Navone and eventually Navona. Innocent X decided to advance the prestige of his already powerful family by enlarging their palace and revamping the square. After many a trial, tribulation and false start, Bernini was chosen and began his modelling of the Fountain Of The Four Rivers. Often, when strolling through this piazza by night, one might imagine the Innocent X of Velazquez's portrait, with his critical, calculating eyes looking down from a high window, at the end of the long gallery frescoed by Pietro da Cortona and which, at night, even today, remains lit, as if forcing us to remember him. From here, the pope would supervise Bernini, watching as his work took shape ~ the palm tree bent double by the wind, the Statue of the Moor wrestling with a dolphin, the rock that a stubborn Bernini wanted removing from the ground in order to then somehow drill into it and, as if by magic, make it anchor an obelisk in place. There also, in this night of reminiscences, are Francis Bacon's 40 plus versions of Velazquez's portrait and the video in which Jeremy Iron's inimitable voice reads the Irish-born artist's words: "I feel hungry for life and that hunger has enabled me to live. I eat, I drink ... until the emotion of creation surges. I believe art is an obsession for living."

Dialogue in a Vatican room

It is also said that “Art follows money” so questions about patrons and power are bound to come up. What is happening today in the realms of the art market? Perhaps even asking would be like putting one's foot in the serpentine hair of Bernini's Medusa. While waiting to enter the Vatican Museums, we remember Damien Hirst's 2017 behemoth of an exhibition in Venice that threatened to raise the roof of the Grassi Palace, home of the Pinault Collections. It all left one a little cold. Today, however, Laocoon and His Sons awaits, as do works by Michelangelo and Raphael ... and a room in which we will be mesmerised by Caravaggio's Deposition of Christ, that vertical painting descending from the crown of Mary Magdalen's head in a straight line direct to Jesus' lifeless hand. Under the cornerstone of the tomb there is only darkness and abyss.

A Bernini angel in front of Caravaggio's Deposition of Christ, Vatican Museum, Rome

What is a Masterpiece? wondered Kenneth Clark in his barely 40-page booklet of lecture transcriptions. The answer? It is art that, having entered the mind of a genius in a moment of enlightenment, is capable of giving us either or both butterflies and a punch to the stomach. Caravaggio, from his space on the wall, establishes a dialogue with the Bernini angel in the middle of the room. A kneeling angel, it was once the mold for a Vatican alterpiece and the iron rods that form his wings are exposed to view, having lost the plaster that used to cover them. Likewise, the tightly-packed bundles of straw that shaped his arms under a layer of clay. He is one angel prefiguring another. And a butterfly punch to the stomach.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Bernini's Rome: For Love Of The Eternal City - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

In 2004, 50 years after Frida Kahlo's death (Mexico 1907-1954), thousands of her personal belongings and artefacts saw the light of day again. Photographs, diaries, drawings, books ... along with pillboxes of her painkillers, orthopaedic corsets, hospital gowns, half-used nail varnishes, combs, a bottle of Shalimar - the perfume she wore to try and camouflage "[her] body's smell of dead dog" - clothes, a Revlon eyebrow pencil and pink silk ribbons for her braided up-do hairstyle. Today, all of these dresses and objects, as if characters in her own life story, have left their home (The Blue House in Coyoacan) for the first time ever, en route to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

In 2004, 50 years after Frida Kahlo's death (Mexico 1907-1954), thousands of her personal belongings and artefacts saw the light of day again. Photographs, diaries, drawings, books ... along with pillboxes of her painkillers, orthopaedic corsets, hospital gowns, half-used nail varnishes, combs, a bottle of Shalimar - the perfume she wore to try and camouflage "[her] body's smell of dead dog" - clothes, a Revlon eyebrow pencil and pink silk ribbons for her braided up-do hairstyle. Today, all of these dresses and objects, as if characters in her own life story, have left their home (The Blue House in Coyoacan) for the first time ever, en route to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

Corset and skirt from Frida Khalo's collection. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

It's a story straight out of a Fake News headline. On Frida's death, the painter Diego Rivera, in an attempt to preserve their intimacy as a couple, ordered two rooms in their Blue House home to be sealed with all of possessions and documents locked inside. The moment the little ensuite bathroom adjoining her studio was re-opened and its contents revealed, so too was the message that Frida was transmitting through her clothes. Both Frida and Diego were intense characters, poetically terrible at times and touchingly tender at others. On the centenary of her birth, the press announced the emergence of some 22,105 documents, 5,387 photographs, 168 outfits, 11 corsets, 212 drawings by Diego, 102 by Frida, 3,874 magazines or publications and 2,170 books. These can be found in various compilations, for instance, Frida: Her Photographs and Frida by Ishiuchi (both RM Editorial).

Frida Kahlo's make-up. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

The discord in Kahlo's body began when she was just six years old with a bout of polio which left her bed-bound for nine months. Doctors, pain and sedatives made their first appearance in her life. When she recovered, she did so with one atrophied leg and a complex born of being nicknamed "peg-leg" by the neighbourhood children. She, however, enjoyed climbing trees and learned to overcome somewhat but one of her legs remained shorter and thinner than the other. She disguised this by layering pair after pair of thick socks and wearing knee-high boots. From this tender age, she was already beginning to speak through her clothing.

Frida Kahlo's boots. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

17th of September 1925: the accident

Frida was 18 that morning she left home with her school books and her boyfriend. “I got on the bus with Alejandro and sat next to the rail with him beside me. A few moments later, the bus crashed into a tram. It was a strange bang, dull rather than violent. The impact sent us flying forward and the rail pierced my body as a sword pierces a bull. A gentleman, seeing my wound bleeding profusely, laid me on a billiard table."

Alejandro described his vision of the incident as: "Frida was left completely naked. Her clothes had been ripped off in the accident. A passenger, no doubt a painter by trade, had got on the bus with a packet of gold-coloured powder. The packet split in half and the gold dust went swirling around her bleeding body." Frida lay there covered with a dew-like sprinkling of gold. The diagnosis: triple fracture to her spinal column, fractured collarbone, fractured third and fourth ribs, dislocated left shoulder, thigh fractured in three places, perforated stomach and vagina, eleven fractures to her right leg, dislocated right foot. The medics of the Red Cross gathered up the pieces of her body under no illusions that she would survive the operating table. Her human capacity to withstand such horrific pain would have seemed impossible to them. As would her indomitable will to live.

On leaving the hospital, her mother settled her in a four-poster bed with a mirror attached above and ordered a custom-made easel. Frida remained locked inside her own world, focused on a mirror the size of a picture portrait. During the day, she read avidly between visits from her schoolmates. Chinese poetry by Li Po, Bergson, Proust, Zola and also articles about the Russian revolution and stamp books by Cranach, Durero, Botticelli and Bronzino. But as night fell, so did the images that devoured her, isolated her and terrified her. “Death dances around me all night long", she wrote to Alejandro.

Diego Rivera recalls how Frida first made her appearance in his life: “One day, I was working on frescos at the Ministry Of Education when I heard a young woman's voice shouting up at me saying, Diego, please come down from there. There's something important I have to talk to you about ... and standing below me was a girl of about 18, nice figure, a bit agitated. She was wearing her hair down and she had these thick, dark eyebrows that met in the middle. They looked like the wings of a blackbird." Rivera ~ then 42, nearly 6 foot tall, 16 stone, already married to Lupe Marín and one of the "Three Great" Mexican muralists of that time ~ accepted the role of Frida's boyfriend. Her family commented that it was "the union of an elephant and a dove".

Diego was her God, her father, her son, her "second accident". Every morning, as if in a ritual, Frida would dress herself up like an idol, designing her costume and jewellery so as to hide the wounds on her body. She adorned herself for him as the women of Tehuana did, seeing in their indigenous clothing a political statement and a vindication of her Mexican heritage. Those outfits comprised 3 pieces: the petticoat, the Huilpil (a square-cut blouse that made her look taller) and her updo of braids and flowers which drew the onlooker's gaze upwards to her head and upper torso and away from the lower part of her body.

Frida Kahlo with Diego Rivera

The Blue House

The building that today houses the Frida Kahlo Museum was built by her father 3 years before she was born and painted a bright cobalt blue to ward off evil spirits. It was then extended by Diego and decorated by Frida to resemble a microcosm of tropical vegetation with cacti, orange trees and Aztec idols perched on a small pyramid where a coterie of animals held court, all humanised by their names.

In 2004, one of the most exciting moments at the opening of the sealed rooms was the discovery of a drawing entitled "Appearances can be deceiving". In it, Frida's broken, naked body appears as if X-rayed, with blue butterflies painted over her leg fractures and a slender pillar in place of her spine. She then, in purple pencil, drew a sheer gown over herself leaving her battle-scarred body visible. It is curious in that Kahlo, who would dress in real life with a view to disguising her disabilities, allowed those very disabilities to be viewed under stark scrutiny in this and other paintings.

Poster for the exhibition based on Frida Kahlo's drawing "Appearances can be deceiving", Coyoacan, 2013

In 1937, Leon Trotsky moves into the Blue House and stays there for two years, making it his revolutionary fortress. It didn't take long for the author of The Permanent Revolution to succumb to the charms of his beautiful hostess. They would speak to each other in English, a language Trotsky's wife Natalia couldn't understand, and Frida would pass him love notes she had hidden in her clothes.

Frida Kahlo with Leon Trotsky

Pablo Picasso, too, would adorn Frida. On a visit to Paris, he gifted her a pair of earrings shaped like hands that dangled and twinkled below her braided hair of bougainvillaea and bows. She was forcing us to look at her face. Her lips, painted bright red, always appeared tightly closed in photographs and paintings alike. She never showed her teeth, hiding the invisible jewels that were her gold incisors and which, for special occasions, she would set with little pink diamonds.

Frida Kahlo wearing the earrings Picasso made for her

Frida Kahlo painting her corsets

“I am disintegration”

In early 1950, Frida was admitted as an in-patient for a year in Mexico City. Diego moved into the room next to hers and the hospital stay became a party: "I always kept my spirits up. I spent a lot of time painting because they kept me dosed up on Demerol. That substance made me happy."

A year before her death, the gallery owner Lola Alvarez Bravo organised an exhibition. It's now April 1953. Diego arranged the transfer of her 4-poster bed into the middle of the space. Frida made her triumphal entrance accompanied by the wail of ambulance sirens. The guests gathered around her as she persevered with the aid of painkillers. She was the embodiment of triumph over pain. Then after this homage came the verdict on her right leg. It would have to be amputated. Frida wrote in her diary: "I am disintegration."

From then on, Frida devoted herself and her time to fine-tuning the new parts of her broken body. Her red boots, the finishing touch to her false leg, she decorated with Chinese embroidery, gold thread and little bells. These are, without doubt, the most enigmatic of all the objects in this exhibition. As are the corsets she had to wear, a stark reminder of her torture. Her relationship with them was one not just of necessity and support but also of rebellion. From then on, we would only ever again see Frida approaching in her wheelchair, preceded by the murmuring jangle of her jewellery.

Meanwhile, death was inching nearer, on tiptoes. She dressed, now, for days and nights in bed painting and this was how she prepared for her departure from life to heaven. She realised she was killing herself. The drugs and alcohol that gave her relief and release were likewise a death sentence. At the age of 47, Frida is cremated. It is said that, on the exit of her remains from the crematorium, Diego swallowed a handful of her ashes.

Frida Kahlo's orthopaedic boot. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Road, London

Curators: Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa

From 16 June until 4 November 2018

(Translated for the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving - - Alejandra de Argos -