- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

If, in a nod to surrealism, Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) metamorphosed into something from one of his own photographs, it would most likely be a little turtle whose shell harboured a poetic soul. Since his first photographs in the 80's, of superimposed veins branching out over human forearms, his camera has never stopped capturing images of hum-drum, everyday objects as we've never seen them before coins, books, clocks, scales, tin-openers stripped of any and all superfluous connotations, objects whose reality he skews, sets free and offers to our imagination as simple signs, loosed from the chains of meaning. Madoz wants his images to slow us down and halt us in our tracks. He wants them so deeply imbedded in our minds and for so long that they become our very own. He wishes them "to always have something different to say to the person who wakes up with them on their wall every morning.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

If, in a nod to surrealism, Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) metamorphosed into something from one of his own photographs, it would most likely be a little turtle whose shell harboured a poetic soul.

Since his first photographs in the 80's, of superimposed veins branching out over human forearms, his camera has never stopped capturing images of hum-drum, everyday objects as we've never seen them before coins, books, clocks, scales, tin-openers stripped of any and all superfluous connotations, objects whose reality he skews, sets free and offers to our imagination as simple signs, loosed from the chains of meaning.

Madoz wants his images to slow us down and halt us in our tracks. He wants them so deeply imbedded in our minds and for so long that they become our very own. He wishes them "to always have something different to say to the person who wakes up with them on their wall every morning. To never wear out". And it was from this poetic wordplay, this expressivity, this expansion of meaning that his exhibition Chema Madoz 2008-2014: The Rules of the Game came into being. But also as a homage to the Renoir film of the same name.

While we wait for Madoz, who is patiently dealing with the media days before its inauguration at Sala Alcalá 31 in Madrid, we have a chat with the event’s organizer Borja Casani who tells us: "Chema's photos are, ultimately, the photographic portrait of an idea".

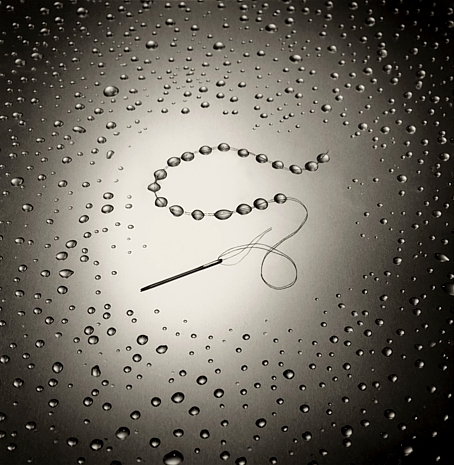

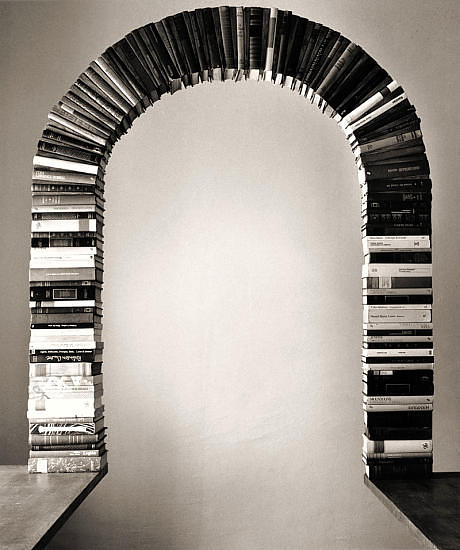

If objects had souls, Madoz would be the one to portray them. He is a seeker of simplicity. He lays all things bare, his aim being to achieve an image that is "austere, almost monastic in its frugality". That's his way of understanding beauty, interpreting it and then offering it to the spectator's imagination, divested of its usual meaning: books built up as the voussoirs and keystones of an arch, water droplets threaded onto a necklace of aqua pearls, a glass watch, an astral card, ... Casani goes on to say: "With Madoz, what you get is a hieroglyph that is already deciphered. He reveals to us a hypothesis and what then happens is that people feel comforted by the fact that they understand it. He presents us with objects we all feel familiar with. They're everyday items to an African, a European or a Latin American. And from this point of view, it's really satisfying to see Chema's success in so many countries. We've exhibited in, for instance, Egypt and people there understood. It's so gratifying, seeing day-to-day objects on display and communicating something to us."

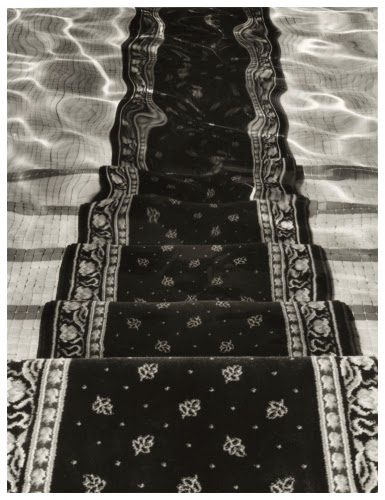

Madoz arrives and what strikes us is his gaze. Shy but scrutinizing at the same time, taking everything in, from top to bottom, fixing on and dissecting whatever grabs the attention of his mind's eye at that moment, lodging itself there, nagging at him until finally it makes its way into one of one of his sketch books in the form of a drawing. And from those pages into an almost surgical transformation on an operating table come carpentry bench where a woodwork square and tools become the sails of a toy boat or the grille bars of an iron door contort themselves into musical notes.

Madoz speaks slowly. He likes a slow rhythm. And silence. These are requisite traits in someone who observes the minute details differently, just as children absorbed in contemplation of an anthill invent a make-believe world around it. "I was an only child and I got used to playing all by myself very early on. I do like people but I need my solitude, too."

Following earlier exhibitions (Reina Sofia Museum, 1999; Telefonica Foundation, 2006) and Spain’s National Photography Prize (2000), the Sala Alcalá 31 exhibit is a compilation of Madoz's work over the previous 6 years, all invariably in black and white, analogue, and on baryta-coated paper, hung side by side under the dome of a basilica-like building that once housed a bank. Curiously, it was Madoz's first ever and much-despised job in a bank that caused the existential crisis that eventually freed him to devote himself full-time to photography.

The harmony of blacks, whites and greys along with the sheer Madrid sunlight flooding the gallery combine to create the very sensation of calm and silence that the artist intended. He would like his audience's attitude to be one of measured serenity, like the reading of a haiku. "This space is wonderful, if a little complicated by so many columns. What Borja and I tried to create here is a simple, elemental setting that "breathes", which I think, happily, we achieved with just the three divisions that permit a certain repose and tranquillity."

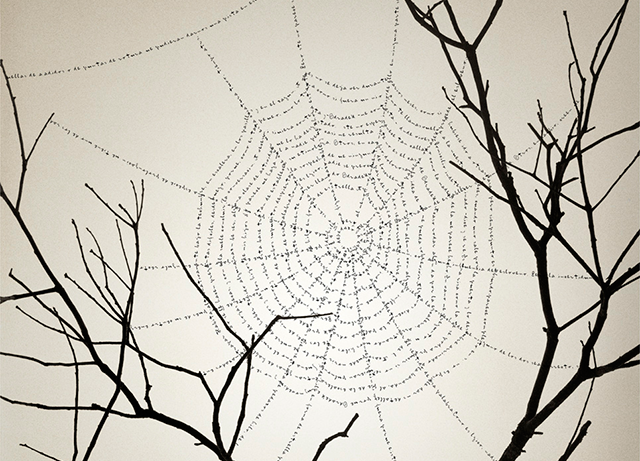

Whilst talking to us, Madoz is drawn to specific photographs and we follow him, observing his choices. There have been a few tangents during his evolution as an artist, albeit subtle ones because the crux of his language has always remained intact: everything hinges on and revolves around the object itself, and always will. However, in this exhibition, he adds or extends some personal obsessions, namely; his passion for calligraphy and the written word; the as yet timid appearance of some pencil drawings; and animal figures. Incidentally, over the course of his trajectory, he has dropped the human portraits from his field of interest due to the fact that, by stripping away their entire identity, their very selves, all he reduced them to in the end was a kind of pretext.

Now, though, he replaces them with mannequins: St Sebastian on a pillar, pierced by arrows that are better known to us as acupuncture needles or the two hollow, wax, pianist-like hands of a woman, their fingers twisting a thread of letters into a geometric puzzle; a reminder of that childhood pastime whereby two friends face to face, and their twenty fingers, manipulate one long piece of taut string into myriad patterns.

This latter photograph serves as the perfect example to ask Madoz about the very many ways his work could be interpreted. Echoing Joseph Beuys’ views on his approach to the creative process : "I've always been interested in creating images that don't 'wear out' even though they're constantly there, visible; images that, despite being viewed on a daily basis, keep enticing you back up close, again and again, making you re-possess them time after time. When you speak of that paused rhythm, that's the rhythm at which I approach the artists who interest me and whose work affects me on a very personal level. To think that your own work might have that effect on someone else is wonderful.” So we talk more about paintings. Madoz admits to a soft spot for Magritte: the clouds, the bowler hats … but also De Chirico and Morandi.

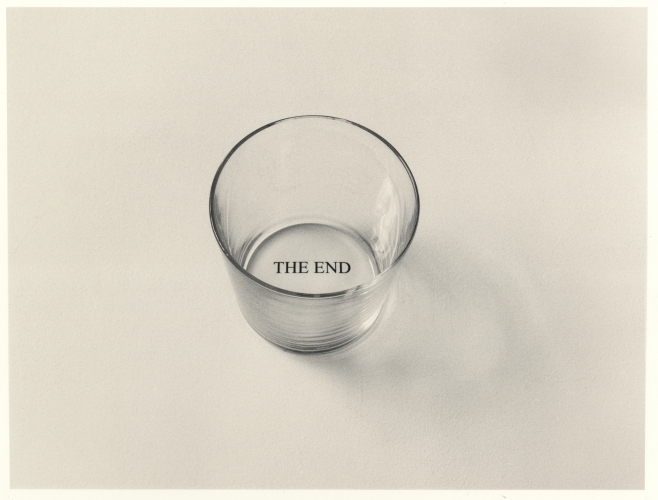

And then he confesses to another partiality: "There's one photo in the exhibition, just an empty glass tumbler on a white background and inside it is written The End. I think it's a lovely photo. The beauty of it and the glow of the glass really move me. And it’s that simplicity that leads, ultimately, to something beautiful. They’re very simple scenarios montages, lit from side on, the object effectively laid bare for us and within our reach. Nevertheless, it isn’t the beauty of a flower that’s being appropriated, or what is generally considered to be beautiful, or whatever represents the idea of beauty."

From painting, we move on to literature: "It's about the ability of verbal language to give us visual images. Gómez de la Serna would be, for instance, an obvious example but also Jorge Luis Borges, Bioy Casares, Boris Vian and Tanizaki. All of them, consummate writers with very personal imaginary worlds."

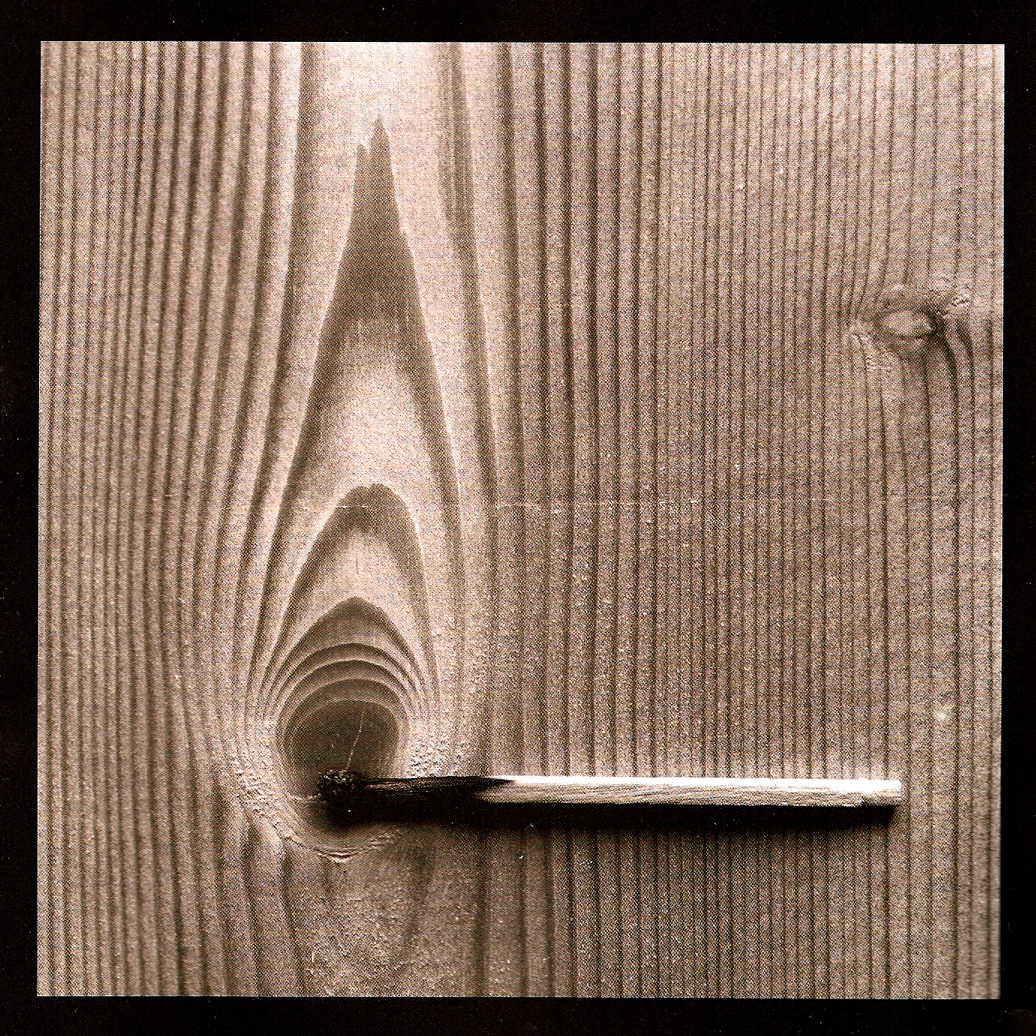

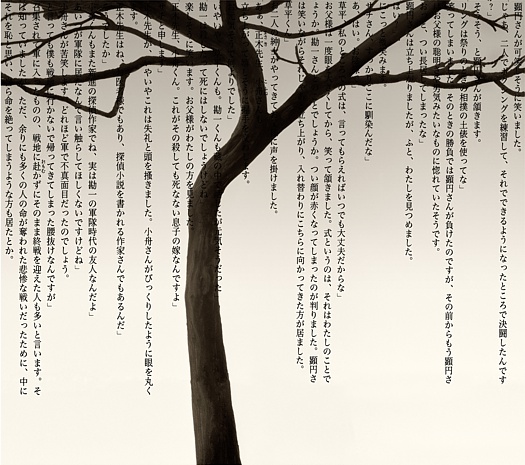

Madoz's studio is a suite of rooms not unlike a treasure trove or Borges’ The Aleph: “a point in space and time that contains all spaces and all time”, his micro cosmos of enough items and ideas to last him an entire lifetime. Out of them all, there's one to which he returns again and again and always will, one that plays on his mind in a never-ending loop: "Books. So simple, so quintessential, that rectangle offering so many possibilities, such varied interpretations and points of view, such depths of semantic richness. That's why you’ll find them so consistently and repeatedly throughout my life’s work. But I always get the sinking feeling that, maybe, one day, I'll run out of ways to use them, not because there are no other uses but because of my own lack of ability. I have my limits but the possibilities of the objects themselves are endless.” We stop now to face a picture of a map in which there appears to be the silhouette of a fish. It's one of his photos that have been heavily influenced by Japanese prints: "It's two negatives, one on top of the other; one is the map lit from above and the other is the fish sketch; and then I projected them both together." They start to resemble animals or animal shadows. Beside this is a picture of the grains and rings of a tree trunk marked out with letters, which confirms the importance of not only the written word but the whole realm of literature to Madoz. He never titles his work: "I have too much respect for writing. I well know a title can give a suggestive dimension to the reading of a piece. I, however, prefer not to give any clues at all and thereby give free rein to the spectator’s interpretative possibilities.”

The art of capturing an object’s essence begins, for Madoz, with the search for it. He is a regular at Madrid’s open-air flea markets where he often finds himself as if overcome by a feeling of stalking the prey that’s been snooping around his subconscious for some time previously. So what causes these “light bulb moments”? "It’s the mystery. I sometimes come across objects that are, essentially, weird. It’s more like them making me feel unsettled and confused. Something tells me to acquire them and make something of them and, generally-speaking, that’s what I end up doing.”

Madoz lives surrounded by the subjects he photographs, as does Kemal, the protagonist of Orhan Pamuk’s novel “The Museum Of Innocence”, who steals everyday household items from the woman he is stubbornly in love with only to make a museum out of them. Madoz, however, is not keen on following in the wake of the trend set in the 1920’s and 30’s by the likes of André Breton and, even more so, Marcel Duchamp during his ‘readymade’ period – a trend whereby the object gets top billing in the art world and has exhibitions to show for it. "I’ve always felt that photography places these objects in a much more attractive and interesting setting. Somewhat like a dream state. Something in your mind or on your mind that’s difficult to put your finger on, intangible. I really like that distance.”

He is well used to living with the objects he’s photographed. They are part and parcel of his predilection: "I’m surrounded by them in my studio. I store them there, often exactly as they were when photographed and sometimes as re-usable material. It’s quite amazing the significance and implications that objects have and how we endow them with powers of evocation. We associate them with life events, moments in time, people and ideas. For me, this was a huge discovery when I first started working with them. I remember once finding a badge I used to wear at school and I was amazed at how it transported me right back to my classmates, even my old desk …”

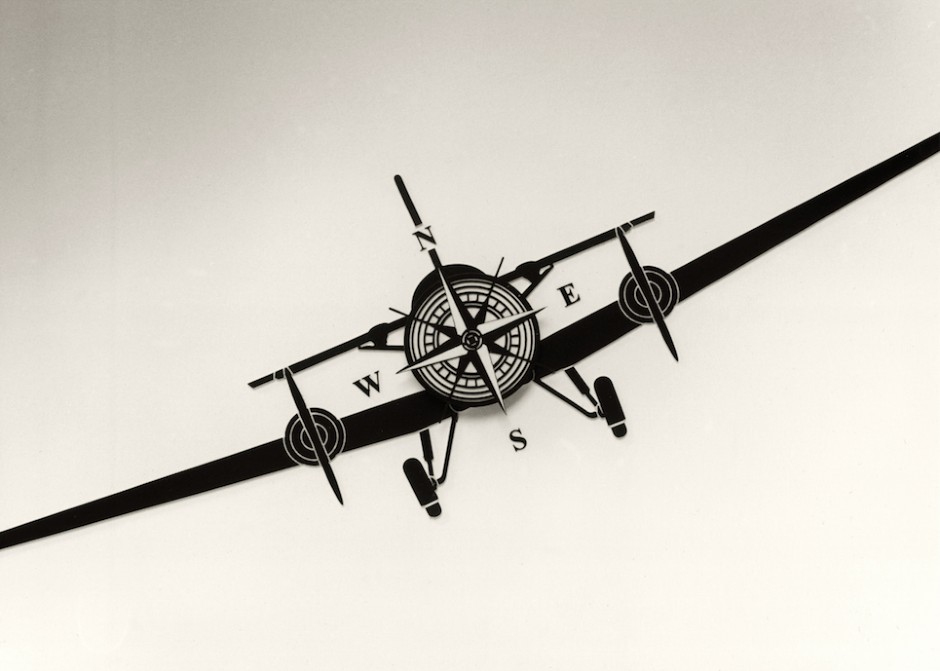

And so we finish our guided tour with the photograph that Madoz considers his most representative. It’s one of a lightplane seemingly made out of a child’s self-assembly cut-outs, black against a white background. Childhood here hinted at as a magical time of creation. On its propellers, Madoz has placed a compass: "At times, I identify with it. It corresponds to my mood; my being always on the move, somewhat disorientated.” And here is where our artist resides, between imagination and contemplation: Chema Madoz, a photographer of few words.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Chema Madoz. A photographer of few words - -Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

The work of Italian artist Tatiana Trouvé (1968), resident in Paris, is grounded firmly on drawing, sculpture and installations, through an inquisitive examination of concepts such as time, space and memory. Her creations and locations are like tracks left by the soul that reveal an inward-looking universe. Her work has been exhibited at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the MAMCO in Geneva, and in galleries such as Emmanuel Perrotin and Gagosian. Trouvé has won the Marcel Duchamp Prize (2007) and has twice participated in the Venice and São Paulo biennials. Her latest work is a sculpture for a public area in the city of New York. The starting point for this work is an observation I made when studying the park and its history, but also, above all, I tapped into my own experience of this place. Central Park is a natural and cultural object, a nerve centre of trends and mobility in the very heart of a city, combining a web of heterogeneous landscapes.

Tatiana Trouvé in her studio whit Lula. Photo credit: Alastair Miller.

The work of Italian artist Tatiana Trouvé (1968), resident in Paris, is grounded firmly on drawing, sculpture and installations, through an inquisitive examination of concepts such as time, space and memory. Her creations and locations are like tracks left by the soul that reveal an inward-looking universe.

Her work has been exhibited at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the MAMCO in Geneva, and in galleries such as Emmanuel Perrotin and Gagosian. Trouvé has won the Marcel Duchamp Prize (2007) and has twice participated in the Venice and São Paulo biennials. Her latest work is a sculpture for a public area in the city of New York.

Tatiana TROUVÉ. Desire Lines 2015. Metal, epoxy paint, wood, ink, oil, rope. 350 x 760 x 950 cm. Photo credit: Emma Cole

Elena Cué: In your public commission "Desire Lines", for Central Park in New York, you created a very poetic work, envisaging a symbiosis between culture and the act of walking. The lengths of the 212 different paths around the park, like living arteries, are portrayed in huge spools of brightly coloured threads. Can you tell us about the cultural and political meaning of this work?

Tatiana Trouvé: The starting point for this work is an observation I made when studying the park and its history, but also, above all, I tapped into my own experience of this place. Central Park is a natural and cultural object, a nerve centre of trends and mobility in the very heart of a city, combining a web of heterogeneous landscapes. In this connection, it is an emblematic project of modernity. That’s why I didn’t want to create a work that was simply one more of the numerous sculptures that have been created in this context. As the artist Robert Smithson said, Central Park is, in itself, a sculpture. That’s why I decided to establish a dialogue with the park. I created a series of routes from all the roads and paths that cross the park and are open for walking. I measured these routes and then transferred their lengths to huge spools of thread, so that adding the lengths of all 212 spools on the three large frames of which "Desire Lines" is comprised gives us the total length of all the roads and routes a person can walk along.

After that, firstly, I identified each spool with the description of the route they contained and the title of a historic march, the work of an artist, a writer or a song about walking to be associated with that particular route: Selma to Montgomery March (21 March 1965), Woman Suffrage Parade (3 March 1913), projects by “walking artists” like Richard Long or Hamish Fulton, poems by Baudelaire or André Breton, essays by Guy Debord or Henry D. Thoreau, songs by Johnny Cash or Robert Johnson… In other words, a set of 212 references linking each of these paths with another path –historical, imaginary, political, cultural– and providing passers-by with a proposal that would enable them to walk again, to walk differently, around the park. And this formula sums it up: “Follow in someone else’s steps”. The act of walking has its own, singular beauty; it is an everyday, banal action, but at the same time it is a privileged manner of protest, of awakening the senses and the spirit, which is the origin of belonging to the world in a subjective way...

Drawing is the key to most of your work. This artistic discipline extends into other works such as sculpture and installations. How important is drawing for you?

It’s true that drawing occupies a fundamental place in my work. As you say, drawing is present throughout my artistic production. I draw spaces, whether in two dimensions or in three. To put it another way, my two-dimensional drawings are images of spaces and, at the same time, my three-dimensional installations build spaces that work like images.

Untitled, from the series Remanence 2008. Pencil on paper, pencil lead, tin, plastic. 82,5 x 119,5 cm

Your drawings of spatial creations are very unsettling, like “The unremembered”. The metaphorical representations of places of thought take us into a dream world, a world of the unconscious. They must be a source of self-knowledge...

I complete these two elements, space and image, present in my work, with a third: remembrance. For me, drawing means making my memory work and this is unquestionably why the terms “mental image” or “unconscious” are so often used to describe my work. However, there is something about the unconscious that interests me in particular, and that is that it is timeless. In the sphere of dreams, all times coexist and are superimposed. This is a dimension I am interested in and I effectively try to give it shape in my drawings.

Why are your spatial interventions always uninhabited?

I am very fond of a quote by the Italian architect Ugo La Pietra, who says “To live is to be at home everywhere”, meaning that to live is, first and foremost, a question of approach. I produced a work called The Guardian. Its title refers to a person assigned to a place on a chair. But this guardian only exists on the device where it is located: a copper rod is placed over the chair (guarding the guardian’s place), and the rod pierces a concrete wall from which, on either side, small bronze and plastic bags are hung. Inside this wall there are embedded works, whose “ghosts” can be seen in the material pasted on its surface. It is an absent sentinel guarding an invisible exhibition, but it is also a device that must be inhabited by contemplation, just as the images intend.

Tatiana TROUVÉ. Untitled 2014. Patinated bronze, copper, paint, concrete, leather, plastic. 180 x 454 x 250 cm. Photo crdeit: Roman März

Your work in “Bureau” is like a kind of “Remembrance of Things Past” since you created a work of art from all the time you had to waste looking for work or doing daily chores that took you away from your artistic activity. How important is the concept of time in your work?

I don’t think of time in its abstract dimensions, on a scale, for example, of cosmic time and its infinite duration. I have seen time as a material of my work since I created Bureau d’Activités Implicites (Office of Implicit Activities), the first module of which I made in 1997. It’s time on a human scale, a time we experience. Hence, its not so much a concept as a reality we experience in its various manifestations: time for waiting, time for searching, time for wandering. But what interests me even more is the coexistence of times. I see time as dual. The present is dual, it has two coexisting facets: the present is the past passing. I have made a series of works called I Tempi Doppi [Double Time]. Each of the works in this series comprises a lit light bulb linked by a copper wire to an unlit light bulb. The past and present feed each other, maintaining a singular relationship whereby one seeks to switch off the other, because the past is also made of present that passes. Time is dual, because it works in a dual way.

What is the most important thing art has given you?

Art has given me what I have taken from it.

“Double Bind” is the name of your first major exhibition in Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, whose title alludes to the irresolvable situation that emerges when we are faced with an intrinsically paradoxical message. What is your interest in opposites and the tension they emanate?

This title, Double Bind, responded to the spatial proposal I had devised for this exhibition at Palais de Tokyo. The tension was in the space itself –there was no psychological component, unlike the standard usage of that expression. And it was not embodied by a contradiction, but by an echoing structure that perturbs our potential understanding of it, causing a feeling of floating between one and the other. Incidentally, what interests me is not the tension itself, but what it opens up: this interstitial space-time or these inter-worlds and the floating attention they generate when we install ourselves in them.

Your work is full of meanings, and there is an interesting underlying discourse. Is the spectator’s immediate aesthetic experience of your work enough, or do you think some prior knowledge is required?

We must trust those who are looking, because aesthetic experience is on their side. There are many ways to activate the potential of the works, but first and foremost you need to be constantly involved. Involvement: “perception requires involvement” is the title of a work by Antoni Muntadas, who asserts that the senses must be emphasised in order to understand a work, but also that anyone can do it using their own means. But, without that commitment, aesthetic experience is not possible. It all begins with this increase in involvement, and this is also what can lead you to research a process or a particular work. Of course, the works offer different approaches to this experience. If I take the example of Desire Lines, a small explanatory text is outlined at the start of the reproduction of the lengths of the paths in the park represented in the spools of thread. Afterwards, it is up to each person to carry on. The simplest way is by reading the titles of the spools and evoking the walks they recall, to which one may add one’s own memories, considering the various complete references of the titles given to the various routes, which make the historical, cultural and political references appear more explicitly, allowing one to submerge oneself in the history of the march. But it is also possible to take a walk around the park, interpreting the present cultural and historical elements, either by reading a poem or a book, listening to a piece of music, or through the documentation on a historical march or artist’s representation.

By activating each of these modes of operation, the person looking/walking will be following in the footsteps of another. To varying degrees, they will place the work in motion. Various readings are always possible, and none is imposed, but the ones that work are all based on an approach proposed by the work itself.

Through your art, are you asking questions or providing answers?

Personally, I don’t think art either asks questions or provides answers. I think art bewilders; in other words, it invites us to think differently, by shifting around our references.

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Paris is paying tribute to Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), one of the most distinguished artists of the 18th and 19th centuries, by according her a magnificent retrospective at the Grand Palais until 11th January 2016. Over 160 oil paintings, pastels, sketches and drawings are on display to illustrate the life’s work of this remarkably gifted painter who dazzled Europe’s finest with her mastery. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun is arguably one of the few women artists given the attention and recognition they deserve, a rarity as "women's art" has traditionally been paid scant regard. Her reputation could even be said to have reached legendary status in art history, the praise during her lifetime and the wealth of critical acclaim ever since never having diminished over the years.

|

Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Paris is paying tribute to Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), one of the most distinguished artists of the 18th and 19th centuries, by according her a magnificent retrospective at the Grand Palais until 11th January 2016. Over 160 oil paintings, pastels, sketches and drawings are on display to illustrate the life’s work of this remarkably gifted painter who dazzled Europe’s finest with her mastery.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun is arguably one of the few women artists given the attention and recognition they deserve, a rarity as "women's art" has traditionally been paid scant regard. Her reputation could even be said to have reached legendary status in art history, the praise during her lifetime and the wealth of critical acclaim ever since never having diminished over the years. Her tumultuous existence make her an especially appealing personality. High society chic during the Ancien Regime, counting down the hours before the French Revolution, the toast of the most exclusive European royal courts of her time and, when she returned to Paris after a long exile, the Napoleonic Empire at her feet. Always conscious of her own talent, she managed to assert herself in a man’s world and deploy the full arsenal of weapons at her disposal to forge herself a niche in an art world dominated by men. With consummate subtlety, she used her own attractive likeness as propaganda for her skill as a portrait artist, with many of her self-portraits revealing the genius, beauty and vitality of this woman determined to reach the top.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée, born in 1755 into an artistic Parisian family, where her father Louis Vigee, a renowned portrait and pastel painter, introduced his daughter very early to the profession. At fifteen, she began her career as a portraitist and in 1774 enrolled at the Saint Luc Academy where her first works were exhibited. Her marriage to the art dealer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun opened new doors and paths to recognition for her. She studied the Old Masters and steeped herself in all styles of art for inspiration. In 1778 she painted the first in a long series of portraits of Marie Antoinette, to which she owed her initial fame, and it was this close relationship with the Queen that helped secure her a fully-fledged membership of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1783. Her first portraits exhibition at the Academy was not received unreservedly but she soon won over her critics and the public. In 1785, her large canvas, "Marie Antoinette With Her Children" caused such envy amongst her detractors they instigated a campaign of criticism and libel against her. Although she defended herself ably, her character had been so effectively undermined as to force her to abandon her natal Paris at the onset of the Revolution and begin a long pilgrimage across Europe.

Her first years in exile were spent all over Italy. Turin, Parma, Florence, Venice, Rome and Naples, to name just a few, were the cities where she lived distanced from her world, a world that would never be the same again. Her fame preceded her and, with that, Italian aristocratic and artistic circles opened their doors and welcomed in the renowned French portrait artist. There being no sign of a possible return to Paris, her exile would continue on for many more years. In 1792, she relocated to Vienna, to work for exiled French aristocrats and for the Austrian and Polish nobilities. In 1795, she travelled to Russia and settled in Saint Petersburg. The court of Queen Catherine II received her enthusiastically and for the next six years she would work there tirelessly and bring about a new understanding of the art of portraiture. Her work received official recognition from the Saint Petersburg Academy of Fines Arts and she was again rewarded with the support of both fellow artists and the public alike. During these upwards of 12 international years, her fame and fortune grew substantially, allowing her a freedom rarely afforded a woman of that era. On the 18th of January 1802 she returned, finally and definitively, to Paris where she would remain for the rest of her life, bar a few trips to England and Switzerland. Her work rate was prolific as she battled and managed to maintain her fame and prestige within Europe’s most exclusive artistic circles. Her salons were where the most illustrious of the day would meet: painters, writers, and philosophers. The passage of time did not diminish her artistic fervour or curiosity as she devoted most of her time to nuancing the art of landscape painting, then made very fashionable by the arrival of Romanticism. A few years before her death, she wrote her Memoirs: three volumes recording the experiences of a life lived to the full, without compromise or complaint. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun died in Paris in 1842 at the age of 86.

Vigée Le Brun's compositions are refined, full of beauty, brimming with life, replete with expressivity and colour innovation that leave no doubt as to the sophistication of her technique. Her portraits are the reflection of a whole era and an unbounded source of research into the ideal woman she herself embodies. Rather than breaking from the stereotypes of the time, her subjects go beyond purely pictorial representation. The poses and gestures of each of her models highlight the importance of her paintings in the study of an entire era. Nothing is depicted by chance. Every scene conceals a multitude of details with a life of their own quite apart from the overt composition. Her work served as a reference point for other painters as she tweaked and customized her themes with the changing times. Examples of this include her allegorical and mythological paintings in the neoclassical style; her Rousseau-influenced paintings of maternal and filial love; and a comprehensive gallery of beautiful and sensual women, each perfectly adapted to her time and place.

One cannot talk of Vigée Le Brun without referencing another great Parisian artist, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1813), who shared her passion for "the easel" and her struggle for recognition in a male-dominated artworld. Both started on the same day at the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture and, due to the similarity of their styles, were constantly compared with each other but, although Labille-Guiard never achieved the international fame her contemporary enjoyed, she did still forge a niche for herself and earn well-deserved recognition for her historical and portrait paintings, along with much success as a teacher. After working at the court of Louis XVI, she reinvented her paintbrushes, adapting them to the new revolucionary times and continued to paint for the rest of her life.

Vigée Le Brun's and Labille-Guiard’s works made a massive contribution to the promotion of Fine Art studies amongst later generations of women artists and demonstrated that the fact of being female was no barrier to expressing one's talent and creativity in a male-dominated world. Both women had presence and visibility in both private and public spheres, brilliant women whose forthright personalities, in a universe dictated by men, revealed a hitherto inconceivable and unheard of reality.

The Vigée Lebrun exhibition is the perfect opportunity to reflect on women in art and to examine the liaison between reality and painting as a mirror reflexion of our world. Her persona represents those same ideals that, many years later, Virginia Woolf would broach in A Room Of My Own, namely: personal and intellectual liberty coupled with an economic independence that could break the bonds of established convention.

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

The galleries of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum have recently opened an exhibition by artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944), successfully curated by Paloma Alarcó, that enables us to “listen to the dead with our eyes”. Paintings and writings come together in the museum’s galleries, divided into emotional Archetypes to communicate this artist’s obsessions from throughout his intense life. People think that you can have a few friends, forgetting that the best, most authentic and above all, most numerous, are the dead. I intend to engage in a series of conversations with the afterlife. As the tormented spirit of the Norwegian artist has circumstantially settled in Madrid, I enthusiastically headed there to learn more. I always felt like I was treated unfairly during my childhood. I inherited two of the worst enemies of mankind: tuberculosis and mental illness. Disease, insanity and death were black angels beside my crib.

The galleries of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum have recently opened an exhibition by artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944), successfully curated by Paloma Alarcó, that enables us to “listen to the dead with our eyes”. Paintings and writings come together in the museum’s galleries, divided into emotional Archetypes to communicate this artist’s obsessions from throughout his intense life.

People think that you can have a few friends, forgetting that the best, most authentic and above all, most numerous, are the dead. I intend to engage in a series of conversations with the afterlife. As the tormented spirit of the Norwegian artist has circumstantially settled in Madrid, I enthusiastically headed there to learn more.

Let’s start with your childhood.

I always felt like I was treated unfairly during my childhood. I inherited two of the worst enemies of mankind: tuberculosis and mental illness. Disease, insanity and death were black angels beside my crib. A mother who died early, planting me with the seed of tuberculosis. A hyper-nervous, pietistic father, religious to the point of being crazy, from an ancient lineage, planting me with the seeds of insanity.

When you think about those years, how did you feel?

The angels of fear, pain and death were beside me right from birth, going out to play with me, following me under the spring sun, in the splendor of summer. They were with me at night when I closed my eyes, threatening me with death, hell and eternal punishment. And I often woke at night and looked around the room with panicked eyes thinking “Am I in hell?”.

The fear of death tormented me, and this fear harassed me through all of my youth.

Heaven and hell, how do you envisage eternity?

Flowers will emerge from my rotting body, and I will be part of them. That is eternity.

And where is God?

With fanatic faith in any religion, such as Christianity, came atheism, came fanatic faith in the existence of no God. And with this non-faith in God there was content, becoming a faith itself in the end. It is generally foolish to assert anything about what comes after death.

But what is it that gives strength to the Christian faith. There are many who have difficulty in believing it. Although one cannot believe that God is a man with a big beard, that Christ is the Son of God who became a man, or in the Holy Spirit formed by a dove, there is much truth in this idea. A God as the power that must be at the origin of all, a God that governs everything. We can say that he directs the light waves, the movement of the tides, the center of energy itself. The Son, the part of this energy that is in man, the immense energy that filled Christ. Divine energy, genius energy and the Holy Spirit. The most sublime thoughts sent by the sources of divine energy to the human radio stations. In the very depths of beings. That which is provided to every human being.

But what do you think death is?

Dying is as if the eyes have been switched off and cannot see anything else. Perhaps it’s like being locked in a basement. You are abandoned by all, they closed the door and left. You see nothing and only notice the humid smell of putrefaction.

And what about life?

I have been given a unique role to play on this earth that has given me a life of illness and also my profession as an artist. It is a life that does not contain anything resembling happiness, or even the desire for happiness.

Not even love?

Human destinies are like planets. Like a star that appears in the dark and meets another star, glistening in a moment, to then return, fading into obscurity. So as well, a man and a woman meet, they slide towards each other, shining in love, blazing, and then disappear, each one for himself. Only a few end up in a great blaze in which both can fully join.

The ancient were right when they said that love was a flame, as the flame leaves behind only a pile of ashes. Love can turn to hate, compassion to cruelty.

Jealously is closely linked with love, how would you describe it?

Jealous people have a mysterious look, many reflections focus in those two sharp eyes, like in a crystal. The look is exploratory, interested, full of love and hate, an essence of what we all have in common.

Jealousy says to its rival: go away, defective; you’re going to heat up in the fire that I have lit; you’ll breathe my breath in your mouth; you’ll soak up my blood and you will be my servant because my spirit will govern you through this woman who has become your heart.

Now let’s talk about art… where does it come from?

Art generally comes from the need of one human being to communicate with another. I do not believe that art has not been inflicted by the need for a person to open his heart. All art, literature as well as music, has to be generated with the deepest feelings. The deepest feelings are art.

What is the purpose of your art?

I have tried to explain life and the meaning of life through my art. I have also tried to help others clarify life. Art is the heart of blood.

We must no longer paint people reading or women knitting. In the future we must paint people who breathe, feel, suffer or love. As Leonardo da Vinci dissected corpses and studied the internal organs of the human body, I try to dissect the soul.

Conclusion.

My art is based on one single thought: why am I not like the others?

How do you think the audience should approach art?

The audience must become aware that the painting is sacred, so that it unfolds before them like in church.

One of your iconic paintings is The Scream, could you explain the origin of such a radical emotional expression?

I was walking along the road with two friends, the sun was setting. Suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stood, leaned on the fence feeling deathly tired. Over the blue-black fjord and city hung blood and tongues of fire. My friends walked on and I remained behind, shivering with anxiety. And I felt the immense infinite Scream in Nature.

Your love of photography is known, what do you think of photography as another mode of artistic expression?

The camera cannot compete with the brush and palette as long as it cannot be used in heaven and hell.

Where is the beauty in your art?

The emphasis on harmony and beauty in art is a waiver to be honest. It would be false to only look on the bright side of life.

Your writing has a strong aphoristic style. We’ll finish there…

Thought kills emotion and reinforces sensitivity. Wine kills sensitivity and reinforces emotion.

- A conversation with Esvard Munch- - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Martín Chirino (Las Palmas, 1925) grew up on the beach of Las Canteras, feeling the sand, the sea and the breeze whilst watching a horizon that he dreamed of moving. The earthiness, ancestry and mythology of his birth place purify the forger’s soul through fire to take a new form in material, in this case iron, arisen from the deepest interior of this wind sculptor. This particular place has rooted him to primeval and his dreams and desires have lead him to that which is universal. The spiral, the symbol of origin and formation of the universe, defines this artist in constant search of the truth. “Look at this sculpture, I’m going to make it a tribute to Picasso. Look at the beauty that’s going to remain underneath, the beauty of the shadows. It’s easy to draw or paint shadows, but the challenge for a sculptor is to materialize them, to give them body weight.”

Martín Chirino (Las Palmas, 1925) grew up on the beach of Las Canteras, feeling the sand, the sea and the breeze whilst watching a horizon that he dreamed of moving. The earthiness, ancestry and mythology of his birth place purify the forger’s soul through fire to take a new form in material, in this case iron, arisen from the deepest interior of this wind sculptor. This particular place has rooted him to primeval and his dreams and desires have lead him to that which is universal. The spiral, the symbol of origin and formation of the universe, defines this artist in constant search of the truth.

“Look at this sculpture, I’m going to make it a tribute to Picasso. Look at the beauty that’s going to remain underneath, the beauty of the shadows. It’s easy to draw or paint shadows, but the challenge for a sculptor is to materialize them, to give them body weight.”

Why don’t you tell me about the shadows of your life?

I believe that we all have an inner character that gives us answers and questions us, a character that you converse with. I am a calm person because I look for the answers within and my surroundings have little impact on me. I realized at a very young age upon reading Demian by Herman Hesse, which struck me in both senses, that the protagonist was always talking to himself and was able to bring out a truth drawn from reality...

And when did you discover your other side?

I am number 12 of my family. I was a kid living in a very big house, on the beach of Las Canteras and from a young age I was in search of my own space, my refuge, in a lost bedroom, so things happened in there. And I think that that’s where my other personality was shaped. I used to sit with my legs either side of one of the doors in the room where we kept the sheets and I always used to hide there.

And with so many siblings, how was your relationship with your mother?

Very good because my mother was an only child, she married my father and started having children. She used to read Balzac and she loved his work because he describes very interesting things and things that reflected life itself. She had no literary judgment but a passion for reading everything. And she read it to the people who she worked in the house with. My mother was a very special person and I always got along with her really well. She was very calm, very soft, but she also had inner strength.

And what do you long for?

I think I’m missing a place where I can belong and just be. My whole life and artistic career has been conditioned by this search.

Throughout your life, what discourse do you think your work has had?

My inspiration has never been divinity, my inspiration is life itself. I’m talking about a spiral that is identity, because it is the spiral of my land and it makes me feel Canary. One day I asked myself why and, in the end, I realized that my fable ability is the same as anyone’s else but what I’ve really done is look and look in a comprehensive manner. I began to study the whole course of the spiral, not only in my town but in others, and how soon you realize that you haven’t discovered everything that you were searching for in any of them. The most that can be said is that the spiral is a cultural symbol, although no one knows why it is present in the whole of the universe.

From the Canaries you settled in Madrid, where you lived for several years, and then left for New York…

From Madrid I ended up leaving for New York, but before that, there was a final touch there: the poet John Ashbery, who had come to Franco’s Spain together with Frank Ohára. I was the translator for both of them because there were not many people who spoke English in Spain at the time. They came for a few days and had to mount an exhibition at the MoMa and as I translated for them, Juana Mordo was always getting angry with me because she thought I hadn’t said what she wanted.

You were an avid reader, what writers have really influenced you?

Many writers, but Joyce was a passion of mine, I also read it in English. I even went to Ireland, to Dublin, after reading Dubliners, to see if I could learn something from that. I didn’t find anything. I asked myself, where were the Dubliners from Dubliners? But in the most exquisite sense, I didn’t get to meet Joyce’s Dubliners. It was too late, it was not the right time in history.

You said he was the cause of your insanity...

Until I gained a little understanding of Finnegans Wake, an impossible work that I then managed to translate into my vision of a Latino man. That’s why it’s very beautiful in Ulysses, when Joyce puts himself in such a strange position, as if he was God. It was set out to achieve a whole, complete thought, it was very difficult, and he didn’t achieve it… no one achieved it.

But we try…

Perhaps our unhappiness lies here.

And apart from Joyce, what writers have affected you?

Ortega y Gasset: he taught me to find a way of expression. It was extraordinary for me and I don’t think that anyone has handled Castilian better, in such a coherent, perfect way as Ortega y Gasset. I had a passion for it, I even carried El Espectador with me as if it were a comic. Then there’s poets, like Antonio Machado, whose thoughts and metaphors I constantly follow.

And do you write?

I’ve never wanted to be a writer because it scares me, because the written word has problems, because you express thought. Rigor will not let me. I write for myself, things about me, what I know, what I feel, what I think. It’s as if I had written myself.

And what about that phrase of yours, that you don’t make a sculpture but you write a sculpture?

I mean that at the time of making them I have to develop a coherent discourse so that it’s understood, it’s as if it’s written. I write about the circumstances on pieces of paper, a beautiful phrase, what I make of it. I interrelate it all to see what’s going on, it’s a way of understanding it.

Are your values unstable as a result of living in such turbulent times as you have?

You are not born with values, but you acquire or improve them over time, enriching yourself. Obviously I, like everyone else, have had great trouble for blindly believing something that was not proven. What the church says is somehow passable, conversable, and everything that is conversable is subject to the possibility of this change. But you have to be aware and then step forward and put yourself in another situation. My mother taught me the most basic values, she taught me to be religious and I do not want to fail her so I’d rather believe than not believe, it is a choice, I do it out of respect for my mother. Because if I want to reverence things, I want to respect…

But do you really feel the faith? Or have you managed to keep it up based on desire…

No, because I think that thought is not only subject to passion, but also the brain. I mean, I said the word “reverence”, reverence is something self-imposed. But no, I have the chance to demand things of myself, like anyone else.

So we’re not talking about faith, but a rational insistence and desire…

Using my brain to keep faith in some values, out of love for my mother.

To keep it, you must practice it… do you consciously practice it?

Of course, I have great respect for others and my mother is the person who I respect most in the world because she taught me things that created great happiness when I was little. And when I grew up she continued being my friend, someone who loved me, and she said to me: you have to really respect others so that they respect you.

Apart from your mother, what other people have affected you most during your life?

One is more frivolous and the other may be more fictitious because he belongs more to the world of art. One is Donatello, someone who impresses me, who has always drove me crazy and his work leaves me shocked when I see it. The other is Greta Garbo, a symbol for me, a cold, untouchable image, I liked her so much…

And what has remained true after so long?

I think the only thing that has really mattered throughout my life is being a liberal, and therefore being liberal and understanding even what destroys me. It’s good, it’s better.

- Interview with Martin Chirino- - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Clelia

Marlene Dumas, born in the Cape Town suburb of Kuilsrivier in 1953 and a native Afrikaans speaker, she graduated Cape Town University in 1975 with a degree in Visual Arts.

Awarded a two-year bursary, she then moved to Holland where she made art her living and primary form of self-expression. From 1976 to 1978, she taught at Ateliers '63, Haarlem and other Dutch institutions. She devoted herself and her time to painting people or places from her own vast collection of photographs or those in newspapers and magazines. Her works were small format, realistic portraiture of an intimacy that divested its subjects of their public persona, instead cloaking them in a criticism of their identity or politics.

Her pieces are figurative trompe l’oeils that provoke a sense of unease. Their language of movement is manifest in each figure. She draws the faces of adults and children, both alive and dead, with insistency and ambiguity. For Dumas, graphology is a subjective interpretation, her doodling somewhat unintelligible, but always carefully chosen and pronounced, each colour making perfect sense, as shown in 1988’s “Waiting”.

The work she produced over a 30 year trajectory was exhibited in a retrospective: "Intimate Relations” between 2007 and 2009. Her initial success was in Japan and next, for the first time ever, in her native South Africa, leading to exhibitions in art galleries and museums in New York, Los Angeles and Houston.

In 1998, Dumas was awarded the Sandberg prize, along with other distinctions such as the Coutts Contemporary Art and the Prince Bernhard prizes. In 2010, the Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa awarded her an honorary doctorate in Humanities and in 2011 she received the Rolf Choque prize. Her creations are part of the collections of international museums and institutions such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Tate Gallery in London, some of which have them on permanent display.

She started exhibiting in 1978 at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and continued in Basil with Documenta 7 in 1982. Her first solo exhibition was in 1983 and one year later at the Central Museum of Utrecht. She presented her series of collages, creations and self-penned text entitled "Ons Tierra Licht Lager dan de Zee” but it was only in 1985 that she exhibited her paintings series: “The eyes of the creatures of the night”. Dumas talks of her pieces in “Sweet Nothings” with unexpected names, texts and commentary.

She participated in the European Art collective exhibition at the Tate in London during 1987. Her work received recognition in Europe and America in 1989 with “The Pink Human’s Question” after which came Documenta 9 in 1992.

Along with contemporaries such as Gerhard Richter, she was part of “Der Spiegel zerbrochene” in 1993, and also exhibited in London at the well-known Frith Street Gallery with Thomas Schütte and Juan Muñoz. She represented Holland at the Venice Biennial of 1995 along with two other women, María Roossen and Marijke van Warmerdam. She participated in prestigious collective picture exhibitions in Africa among other countries, with “Paintings at the Edge of the World” in 2001 and “Paintings of Modern Life” in 2007. The last decade has seen her exhibiting in cities like Chicago, Venice, Tokyo, Paris or New York to name but a few.

Dumas defines herself as a “collector of images”. Exhibits like “Models” in Salzburg and “Suspect” in Venice present us with advertising bumph, models, corpses and objects that mutate into the spectacular. Grouped into categories, her works are artificial still lifes, parodies, deconstructions or commentaries drawn and painted in watercolour or gouache. One of her pieces, "My mother before she became my mother", sold for $2,000,000 in 2011.

She is currently based in Amsterdam where she continues her artistic work. Dumas’ “The Image as Burden” exhibition was housed at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam from September 2014 to January 2015.

She is one of the great painters of her generation, an artist who centres the human body and human psychological valour, painting her subjects from the cradle to the grave. The cycle of life illustrates her ideas on the social, the sexual and the racial. She keeps up appearances without conclusion, with brush strokes so faint and light of touch they are almost hidden and perhaps more dramatic for that. Dumas borrows images and expresses them “otherly”, making them confusing within the confines of a dark terrain. Her graphology and explicit language can be understood from the titles she gives her work, which generally is portraits, as well as nudes one would swear were blushing at their own exposure being contemplated. Dumas says of her art: “What is at stake and what matters is not the medium an artist uses or the subject matter but his or her motivation, which have become suspect.”

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

This little journey begins on a wall. As dusk falls, so begins a dialogue between that wall and a window, a transparent, vertical frame that reflects in the Swiss meadows outside and surrounding the Beyeler Foundation, all fresh, serene, rose-tinted; set against the electrical charge of a horizontal canvas turned into a muted scream depicting the Wailing Wall. It’s Ernst Beyeler and Renzo Piano in the company of Marlene Dumas. One of those rare moments for meditation: architecture resting its hand on the small of the painting’s back to guide it through a perfectly synchronised, beautifully choreographed dance.

Ernst Beyeler was one of the greatest ever art dealers, In 1970, along with Trudl Bruckner and Balz Hilt, he created the Art Basel fair. He and his wife Hildy aquired a world-class collection of masterpieces and commissioned the architect Renzo Piano to design an exquisitely beautiful museum in which to house them. It opened in 1997 not only to exhibit the Beyeler’s own private collection but also to showcase the world's most important contemporary art exhibitions.

Until 6th September 2015, the Beyeler Foundation museum was the venue for Marlene Dumas’ The Image As Burden, a retrospective of 40 years worth of work comprising over a hundred pieces.

Broken White, 2006.

The Burden of Apartheid

Marlene Dumas (Cape Town, 1953) is an artist who sails deep through the swell of waves and dense, eclectic backdrop that is her work, and very much at odds with her physical appearance it is, too. She is slight of build, bubbly, with playfully expressive pale blue eyes, a booming laugh and a fresh-seeming joie de vivre

But behind that facade, Dumas is a tireless worker and avid collector of postcards since early childhood and still, even today, in her untidily tidy Amsterdam studio, she has everything filed, ordered and catalogued. Dumas, whose figurative style centres the human face and the human body, never works from a live model. She invariably works from a flat, printed, two-dimentional image. Her sources are the hundreds of thousands of photographs cut from newspapers, magazines, some of them pornographic, books on the mentally ill, the “lunatics”: a word she says she likes because of its association with the moon’s influence on our states of mind, catwalk models, “I cannot conceive of a trip without Time magazine”, pamphlets, art postcards and, most of all, her own polaroids. “One could say that South Africa is my content and Holland my form. And I think, as well, that the images I use are universal, known to everyone. I deal in second-hand images and first-hand experiences. My models have already been moulded and posed previously by somebody else. There are no virgins here.” she insists.

Mamá Roma, 2012.

Dumas paints from a place of condensed reality. Hers is painting that questions. Or targets with the precision of a dart. Expression, mystery, the connection between public and private, dreams and reality. Take that portrait in blue of Amy Winehouse. Isolated figures, usually with no background, abandoned in the solitude of a canvas and its sadness.

Dumas is fully aware of the power of the photography and films she has been addicted to her whole life. It was from celluloid, and the looks to camera of its actors, that she learned the rules of imagination. She knows she must surpass the magic of photography and magnify the power of the filmed image in order to justify painting them. This is the motive behind her characteristic focus: the zoom button here, a close-up there, chopping and cropping into strange dimensions. See her paintings of gigantic babies. “I’ve never had the first clue about the actual size of a head. Anatomy never interested me.” she says.

Amy-Blue, 2011.

Her themes are extreme and recurrent: death in multiple aspects and facets. Paintings such as The Kiss (2003), Lucy, Stern and Alfa (2004) are large canvases of dead, apparently serene, women. They are oil on canvas but have a strange, aqueous, veil-like consistency, as if the contours and the colours of these heads were seen through the filter of a memory, dream or nightmare. Violent deaths: Dead Marilyn (2008) or Dead Girl (2002), the head of a young Palestinian girl falling down lifeless, killed. The death of the Dutch film director Theo van Gogh or a dead swan, its sinewy neck and unfurled wing white against a black background.

The Swan, 2005.

And then there is race, above all else, race: its message, its meaning, Dumas’ use of the colour black. Racism that stretches from Apartheid to the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem. The Wall (2009), The Widow (2013). Dumas inherited from Gerhard Richter an interest in “series” painting and also, by the same token, an interest in hanging pictures in such a way as for them to be grouped together in rooms by theme. She is able to fill whole spaces with hundreds of drawings of little tiny heads in black and white, each one unique and distinguishable if only from its expression. There have been multiple series sets since Models (1994) up to and including her latest and as yet unfinished Great Men (2014).

Models, 1994.

At a time in Madrid when the memory of Zurbarán’s Christ and Van der Weyden’s recent departure are still fresh in our minds, the two series of Crucifictions and the portraits of Christ in Dumas’ The Perfect Lover are akin to questions. Van der Weyden’s St John, desolate at the foot of the cross in the 3 metre high Calvary, was powerful but were there ever any Christs as abandoned to their solitude as Dumas’ Gravitá (2012), or Solo the year before?

Gravitá (detail) 2012.

And at the other extreme, her pornography series: strippers, nightlife, neon lights, young men in explicit poses, young girls midway between innocence and abuse, leather boots, black stockings ...

"I paint because I’m a woman” she says. “I’ve always wondered why the great themes of life and love must be conceeded to film directors, authors or pop stars. I want to paint all of that, too.” And her pictures became ever and even more intense. Peter Schjeldahl, in the New Yorker, said that Dumas’ pictures are loaded with such weight that it’s a mystery how they don’t fall from the wall and break the floor.

Leather Boots, 2000.

A farm in Africa

Like Karen Blixen, Marlene Dumas also had a farm in Africa. Of Boer descent, her roots were forged by the essence of rural Afrikaaners: a solid, conservative milieu, strong religious principles but also openness and tolerance. Her childhood in Kuilsrivier (a Cape Town suburb) was a quiet, happy one, with a close-knit extended family of three grandparents and her Dutch mother, a woman wholly devoted to flowers, her three children and her vineyard. Marlene drew in the sand and learned from illustrated books and bibles. She enjoyed open-air cinema on Saturday afternoons. She had two brothers, one a viticulturist and the other a theologian from whom she learnt what it is to have a certain moral maturity and, more importantly, what it means to have a vocation. They were a close family, appearing not to need anything from outside their insular world. In 1976 she won a scholarship to study in Amsterdam where she still lives today: "My homeland is South Africa, my maternal language is Africaans, my surname is French .. I sometimes think I’m not a true artist because my heart is too divided up. My studio is my house. I think I’m like a snail, always carrying its life and homeland on its back.

The Blindfolded Man, 2007.

Marlene Dumas’ studio has no natural light. It’s small, white-walled, cement-floored, spattered by decades of work and paint. Almost everything is on the ground, photographs, brushes on paint pot lids and a small wooden brick she only very occasionally steps on to observe the results of her work. Now 62, Dumas often paints on the floor, on all fours, on a stretch of paper much larger than she is. She paints very fast, spasmodically, like an image captured in an instant on her retina, like water coming into contact with a black paint stain. From here emerge the fine black brush strokes that trace the eyes of a young nude. The water and the paint move around the paper leaving an abstract marking somewhat reminiscent of Bacon, of rivers or of a face reflected in the water at the bottom of a well.

"I’d love my paintings to be like poems. Verse is like naked words that have undressed themselves.” she says. Everything to do with Marlene Dumas aquires a literary density. She writes with her paint and she writes without making books, essays and poetry redundant. She also sometimes writes short phrases in some of her pictures. She likes to write her own exhibit material and press releases as she doesn’t see why or how anyone else should or could define what her art is trying to say. She has always considered herself a descendant of Alexandre Dumas and, for that reason, a “musketeer”, a warrior armed with both pen and paintbrush, too.

The Widow, 2013.

It is also Dumas behind the suggestive titles of her series or exhibiitions: The Eyes of The Night Creatures, Measuring Your Own Grave or her latest, The Image as Burden, yet one more example of the sheer quantity of layers, meanings and nuances in everything Dumas does. This last title comes from one of her small oil paintings of the same name. In it a man, posed Pieta fashion, holds a woman, the image, lifeless, in his arms. He looks at her tenderly and supports the weight of her body with no small effort. Dumas explains that the origin of that pose was a scene from George Cukor’s film, Camille, in which Robert Taylor carries Greta Garbo’s white-clothed body. Dumas’ scene emerges from a black background, two outlined profiles, almost African mask-like, are painted in Dumas’ smudged, discoloured tones, as if with dirty brushes: from black and deep blue to white. Black paint in an old kitchen tin thrown onto the floor of her studio is, perhaps, what Apartheid meant for Dumas.

The Image as Burden, 1993.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Marlene Dumas at the Beyeler Foundation - - Alejandra de Argos -