- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

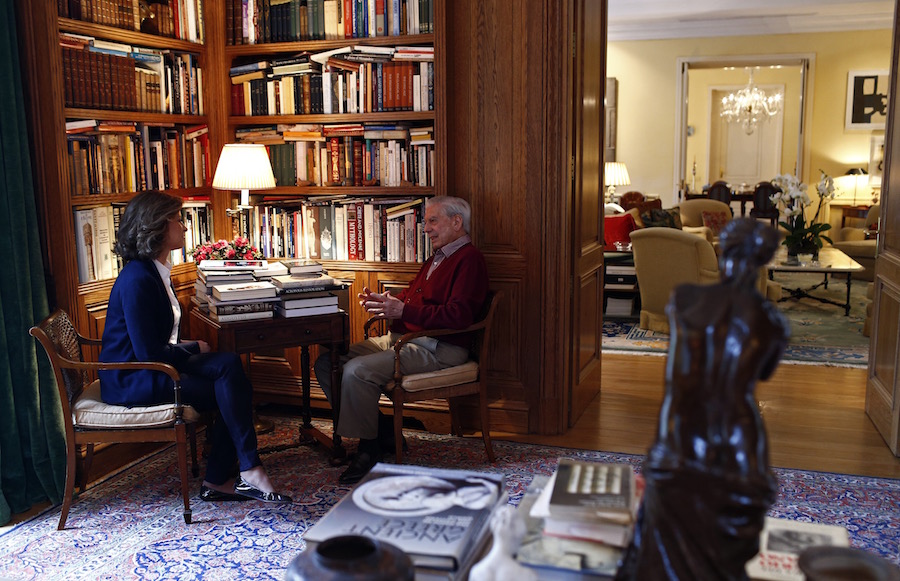

Courage, that virtue exhibited by some mortal beings, is what I would highlight about the Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru, 1936). The writer is devoted to any number of activities with a discerning spirit. Destined to live a disciplined life, as a life of literature demands, he does not hesitate when circumstances require him to take action; for example, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency of Peru in 1990. At the time he believed his moral duty was to become an active participant in public life and, as a democrat, to denounce authoritarian governments wherever they may be found. Or when he went on stage to act for his love of the theatre and, in short, so many other things one might mention… Working in his study, surrounded by books, I am greeted by the Nobel Prize winner, who raises his head upon my arrival with a smile and that pleasant tone of voice of the people of Lima. How are you?

Author: Elena Cué

Courage, that virtue exhibited by some mortal beings, is what I would highlight about the Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru, 1936). The writer is devoted to any number of activities with a discerning spirit. Destined to live a disciplined life, as a life of literature demands, he does not hesitate when circumstances require him to take action; for example, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency of Peru in 1990. At the time he believed his moral duty was to become an active participant in public life and, as a democrat, to denounce authoritarian governments wherever they may be found. Or when he went on stage to act for his love of the theatre and, in short, so many other things one might mention…

Working in his study, surrounded by books, I am greeted by the Nobel Prize winner, who raises his head upon my arrival with a smile and that pleasant tone of voice of the people of Lima. How are you?

Elena Cué: Why don’t we begin by talking about your latest novel, Five Corners, to be presented tomorrow? What does this novel mean to you at this time of your life and your literary career?

Mario vargas Llosa: Well, this novel, as practically all the stories I tell, came about in a way that is very mysterious to me. I had an idea, which was to tell a story about yellow journalism, that is, sensationalist journalism, which I believe is one of the hallmarks of our time. I think yellow journalism is something that appears everywhere, in the underdeveloped and developed worlds alike. And it is a kind of journalism that played a significant part in the Fujimori dictatorship, when the regime used the sensationalist press to intimidate the opposition, to try to tackle opponents with the threat of a scandal –a scandal that had nothing to do with their profession, but with their private lives, and which so often consisted of merely artificial fabrications, slanders to smear and discredit them. This was systematically used by the dictatorship against all its detractors.

The book begins with an unconventional erotic situation…

I think that it is the treatment of what is erotic which determines whether the erotic is elegant or vulgar, subtle or crude. It is the treatment, the words, the way the entire scene is conceived… In and of itself, eroticism entails a certain amount of civilisation. I think that in a primitive society or people there is no eroticism. Sex is the venting of instinct. In sex the animal component prevails over sensitivity, over the formal component. Eroticism is born at a time in civilisation when sexual instinct becomes deanimalised and enriched with contributions from art and from literature. A world of theatricality emerges around the act of love. And this is eroticism. When this is degraded or debased –due to poor performance, ineptitude, the lack of skill of whoever describes or depicts it– pornography then appears. But I think that eroticism has to do with civilisation, with a concern for social mores, with a certain culture, which is what really sublimates pure sexual instinct.

Then we must speak of Freud… Do you agree with the concept of sublimation of sexual desire as artistic creation?

Yes, without a doubt. I think he was very right about this, and I also think he was very right about sex being a primordial function of life. But it is neither excluding nor exclusive. When, for instance, in literature and art in general, sex prevails in such a way that it manages to obliterate the rest, it becomes something very artificial, something that does not truly represent what real life is. I don’t think that the perspective of sex is essential to understand everything. Psychoanalysis went this far, Freud went this far, but we must take a step back from his genius, which is indisputable.

Can the imagination sublimate an erotic experience in such a way that it surpasses the actual experience itself?

I think that the imagination, sensitivity and culture can enrich the erotic experience in an extraordinary manner, but to go as far as to exceed reality, I think not. Reality is the richest thing there is, the most important thing there is. Our imagination allows us to live an artificial life that is wonderful, extremely rich, but I don’t believe any artist would dare to say that artifice is better than real life.

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

Have you ever been surprised when you have re-read what you’ve written and wonder how it was you who produced it?

Yes, I am always surprised when I write. I would go as far as to tell you that the most exciting and most stimulating moments when writing a story happen when sudden things emerge. For example, in Five Corners, there is a character who, when I created him, was going to be a relatively minor one, a sort of secondary character. However, as has been the case on other occasions, this character started to gain strength, began to grow larger as I developed the story, as if, on his own initiative, he had decided to take on an increasingly important presence. I believe that these are the most fascinating moments. Suddenly a character comes to life…

And what barriers do you have to overcome in your creative process?

Well, perhaps the greatest one is lack of confidence. You know, contrary to what one might think, the fact that I spend a lot of time writing, or that I have published many books, does not give me confidence: on the contrary, it increases my insecurity. Perhaps because due to greater self-criticism or perhaps greater ambition. But the insecurity I feel when I begin a story, whether it is a novel, a play or even an essay, is much greater than when I wrote my first works. However, I know that with the help of perseverance and constant work, I can defeat that lack of confidence.

I assume that for a writer, writing is a way of life. You observe and analyse everything in a different way to the rest. Where do you think these differences lie?

Your question refers to an expression that is similar to something that Flaubert wrote, which was “writing is a way of living”. I believe that this is totally accurate. Although the way it is done varies from writer to writer, of course, I do believe there is a kind of dedication, of devotion, that means the writer also carries a kind of spy within him who, while experiencing –taking part in real life, with friends, lovers, frustrations– there is someone within who is watching it all and deciding how it might best be used in his work as a writer.

In your case, what has proven more fertile for your literary inspiration: suffering or happiness?

I think it is wonderful to experience happiness. I do not think it is a raw material, at least in our time. Perhaps in the past, during certain times; but in our time literature, art, creativity are sooner fired by adversity, negativity, fear, pain, resentment, suffering, than by enthusiasm, excitement, happiness… I think this is why the art of our time has a somewhat dramatic and tragic slant. It is not an art or a literature of contentment, of acceptance of the world as it is. On the contrary, I believe that there is a very strong rebellious spirit in all manifestations of the art of our time and this is basically because it is fundamentally much more inspired by what is negative than what is positive in life.

Perhaps artistic creation is a way to mitigate pain, a way to channel negative emotions…

Exactly, a way of expressing a kind of frustration of resentment or even nostalgia for something you do not have.

And can one get to feel that release through whatever artistic language: painting, writing?

Art is a form of knowledge. Art helps you get to know the life you live in a deeper, much more intense way, because there is usually little distance with the life one lives. But art provides you with that perspective, that horizon, which enables you to understand the world as it is, the drivers, the mechanisms lurking behind behaviours. This description of a secret reality is what art provides, much more than history, sociology and any other social science.

And can one feel that release?

In the end it feels, indeed, like a catharsis. You unburden yourself from what seems like an enormous weight. But you only discover what it is and what is looks like when you are able to express it, via literature, painting, music or any other creative manifestation. You can feel really bad but you don’t know why. And I think that one of the wonders of art is that is enables you to articulate that which is uncertain, confusing, a source of terrible angst. But how wonderful when you see that art gives it a shape and makes it communicable. Many times that sensation, those moods… you don’t know where they come from. One suffers from these moods, but one lacks a deep explanation for them. And I believe that this can only become clear when literature or art allow you to stand back and to appreciate life with all your feelings, instincts and intuitions. I think it is one of the main roles of art: to portray that which is the deepest, the most secret within us.

Then you have succeeded, perhaps, in getting to know yourself by expressing yourself –probably that which you say you don’t know what it is, that comes from the subconscious, in a non-instinctive manner– and have been able to recognise it later.

Sometimes you are surprised and others you are frightened. You ask yourself: “Was that inside of me? Did I have that inside? Where did that come from?”

Of course “this comes from me?”

Works of art are secret autobiographies. And perhaps literary works more than any others, because they are so explicit, so direct. They are not as symbolic, like music, for instance. It is also autobiographical, but so much more abstract. Literature is not at all abstract; it is very explicit, very concrete. It is an x-Ray of the human interior, human nature, the human condition; and one can be horrified at the monsters that emerge from within. But they have a cathartic function, and you are liberated from them at the same time.

It is a very healthy way to live. As an agnostic, where do you find the spirituality that religion brings to believers?

I think I find it in culture, in art, in literature. A kind of spirituality manifests therein. It is something that extracts from you that spiritual dimension that others only find in religion. But I believe that an agnostic does not necessarily have to be a materialist in the strictest sense of the word. You can live an intensely spiritual life through art, through culture, or through having a secular spirituality. Every agnostic has a certain anxiety when faced with that unconscionable thought of: “well, this is all there is, and when life ends all else ends”. It becomes extraordinarily strange and surprising like the idea of God, like the idea of life after death. It is very difficult, using only reason, to think of the afterlife, to think that there is another dimension…

Talking of the idea of death, how can literature fight against thoughts of death?

One of its extraordinary powers is that it allows us to live many lives. It takes us out of our reality and makes us live extraordinary realities, rich lives, adventures out of this world, makes us take on so many personalities, psychologies, mentalities… it is an extraordinary enrichment of life. However, at the same time, literature is not a guarantee of happiness; on the contrary, in some way, it renders you much more unhappy because it makes you understand there are many lives that are richer than your own. You become aware of your insignificance.

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

You have many childhood memories. Is childhood remembered or reconstructed?

Well, I think that one remembers in a relative way, because memory is very tricky, very selective. Memory erases or adds many things, because this helps you to live. I don’t think memory is absolutely objective, but I do believe that it is faithful to what you are, because even the transformations, the deformations that nostalgia or fantasy inflict upon memory are also a portrait of what you are, what you lack, what you would like to have but do not have… This exercise of memory, at least for a writer, is fundamental. In fact, Freud said that the years that form a personality can be found in childhood, in adolescence.

What has love meant in your life?

Love is, like literature, something that enriches life in an extraordinary way. I believe that it is difficult to communicate. Love is something that is lived in privacy. And that relationship, which is so intense –probably the richest relationship between human beings– at the same time requires great intimacy, requires a kind of confidentiality to be preserved, because when it becomes public it deteriorates, it becomes banal, does it not? But it is the most enriching experience there is. Everything is different when you live a great passion: things are better, everything is more beautiful, you face life with optimism, and only love gives you this. It is the fundamental experience, the most enriching and, at the same time, the source of great suffering, of course. Tragedies come from love, from unhappy love. The idealisation often made of the relationship often clashes with reality. But even so, I think no one would be willing to give up on love, despite being aware that love also has traumatic –sometimes terrible– consequences. But nobody gives up on it. Because to live that experience is to live the experience of all experiences. The fullest, the most intense, the most absolute.

And what is the meaning of love at your age?

I think that love has little to do with age. Well, the love of a young person is more idealistic, more innocent. The love of an adult, of an elderly person, naturally, is a love made up of lots of accumulated experiences, it is lived with more wisdom, with a better knowledge of reality. But aside from these differences, I believe that the elation, the joy, the feeling of optimism in life that love gives you is exactly the same as when you are a teenager.

Let’s speak of you book “The Civilisation of Spectacle”. Do you think that high culture no longer aspires to change the world?

Well, what I think is that high culture is disappearing. This, I believe, is an alarming tragedy –which is one of the reasons I wrote this essay– as high culture is, thus, naturally elitist. It is something reserved for a minority, and it is very naïve to think that high culture is accessible to everybody. Not everyone has the interest, the curiosity, the patience or the discipline that high culture demands.

On the other hand, the idea of culture being within reach of everyone is a good one. Who could possibly be against this? However, at the same time, if this means –and, unfortunately, in our time, it has led to this– that culture, in order to be accessible to all, needs to become trivialised, impoverished, and become but a pastime, a form of entertainment, then the result is clearly highly negative.

And I believe that this is a great flaw in the education of our time. The education of nowadays does not preserve high culture, but regards it with contempt. The art of creating or of thinking requires looking back into the past, because the present paints a fairly barren landscape in this regard.

Do you think that cybernetics have contributed to this desertification?

Without a doubt. Intellectual effort is gradually diminishing, because technology helps us give up making such an intellectual effort.

What role do you think intellectuals should play in current political life?

Look, I belong to a generation that was highly influenced by the ideas of existentialist thinkers. And although in many regards I have moved away from Sartre and am very critical of his work, I believe that his idea of the writer’s or the intellectual’s commitment to his time, to his reality, to his society, was absolutely correct. One cannot write, or paint, or compose by dispensing entirely with the problems of the world one lives in; and it is fundamental –particularly, if you believe in democracy– that everybody participates in the search for solutions to the problems: for answers to the great questions asked by society, in order to create a system where one can co-exist with all others, with one’s differences, ways of being, one’s own desires…

This is fundamental and, furthermore, I believe that true literature, true art, must address this situation. The main problem is that, nowadays, ideas are less important than image. I believe that pure technology is not enough and that the presence of ideas in public debate is paramount for our understanding of human issues. But in our time this seems to have been relegated and replaced by screens and pictures.

Because less effort is required.

It requires much less effort. But I don’t believe it should be this way, not at all. There is no historical law steering society in that direction. It is our decision. I think that, despite the importance of technology –this is undeniable–, it is necessary for ideas to continue to play a leading role in the life of societies, unless we wish to become a society of robots. I shall refer once again to Orwell, who was so insightful in imagining a world completely controlled by technology, a dictatorial world. Like The Republic of Plato, don’t you think?

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

- Details

- Written by Clelia

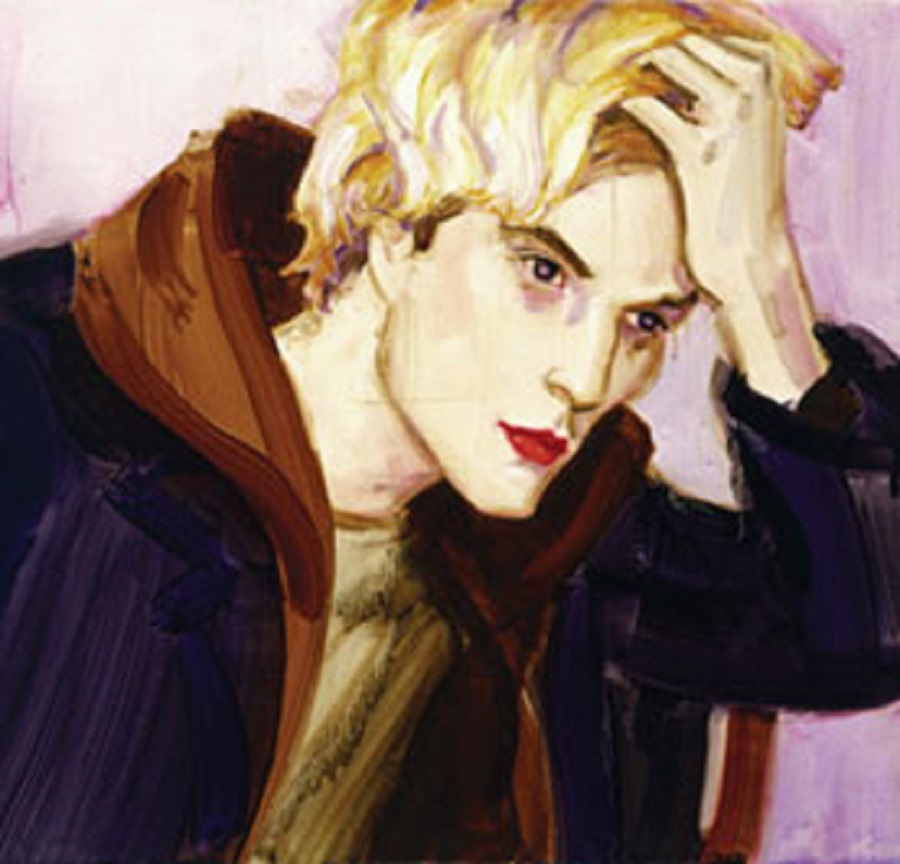

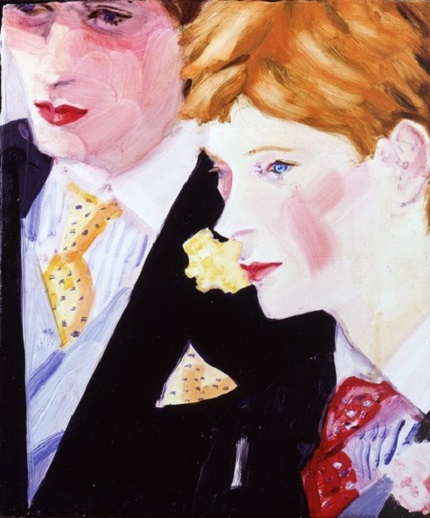

Awarded the 14th Annual Larry Aldrich Contemporary Art prize for "significant impact on visual culture", Elizabeth Peyton (Connecticut, 1965) is an American painter, photographer and multimedia artist. After a childhood steeped in artistic influences, she graduated from New York's School of Visual Arts with a degree in Fine Arts and the ability to draw with her left hand, having only two fingers on her right. She became an assistant to Ronald Jones and also worked in picture archives. She was married to the artist Rirkrit Tiravanija from 1991 to 2004. She currently lives and works in New York City. Renowned as a portraitist of famous figures from the world of entertainment, literature and history, she paints from published editorial photographs, both old and recent, or from her own private collection of snapshots.

Awarded the 14th Annual Larry Aldrich Contemporary Art prize for "significant impact on visual culture", Elizabeth Peyton (Connecticut, 1965) is an American painter, photographer and multimedia artist. After a childhood steeped in artistic influences, she graduated from New York's School of Visual Arts with a degree in Fine Arts and the ability to draw with her left hand, having only two fingers on her right. She became an assistant to Ronald Jones and also worked in picture archives. She was married to the artist Rirkrit Tiravanija from 1991 to 2004. She currently lives and works in New York City.

Elizabeth Peyton, available at http://thegentlewoman.co.uk/

Renowned as a portraitist of famous figures from the world of entertainment, literature and history, she paints from published editorial photographs, both old and recent, or from her own private collection of snapshots. Her every picture captures the influence on her life of well-known personalities such as Oscar Wilde, Napoleon or John Lennon, this latter canvas selling at auction for a record US $800,000 in 2005. She also paints those lesser-known or unknown to a wider audience: 'Craig', for instance, 'Ben' or 'Spencer', titles identifying just the sitter's name but no further clarification or clues whatsoever.

John 1971, available at http://www.moma.org/

In 1998, Peyton published her book "Craig", combining journalistic notes, photographs and drawings, with the aim of showing celebrities like Princess Diana or Johnny Rotten in more informal, intimate settings and endowing them with almost angelic overtones. She has made this comment about her art:"I like the idea of beauty coming from lots of things and that it's not easy to get there." In each of her portraits, however, she manages to capture the spirit and human qualities of her subjects, making them more approachable to the spectator, less distant and stripped bare of any airs and graces. She envisages her subjects in a space that transforms them into something familiar and close, like something or someone we see everyday. "Celebrity, in itself, is of no interest to me as such ... I just think about Art and what it means for society." she was quoted in one of her interviews.

Elizabeth Peyton 1 (2009), available at http://www.simonettaatrezzoeinteriorismo.com/

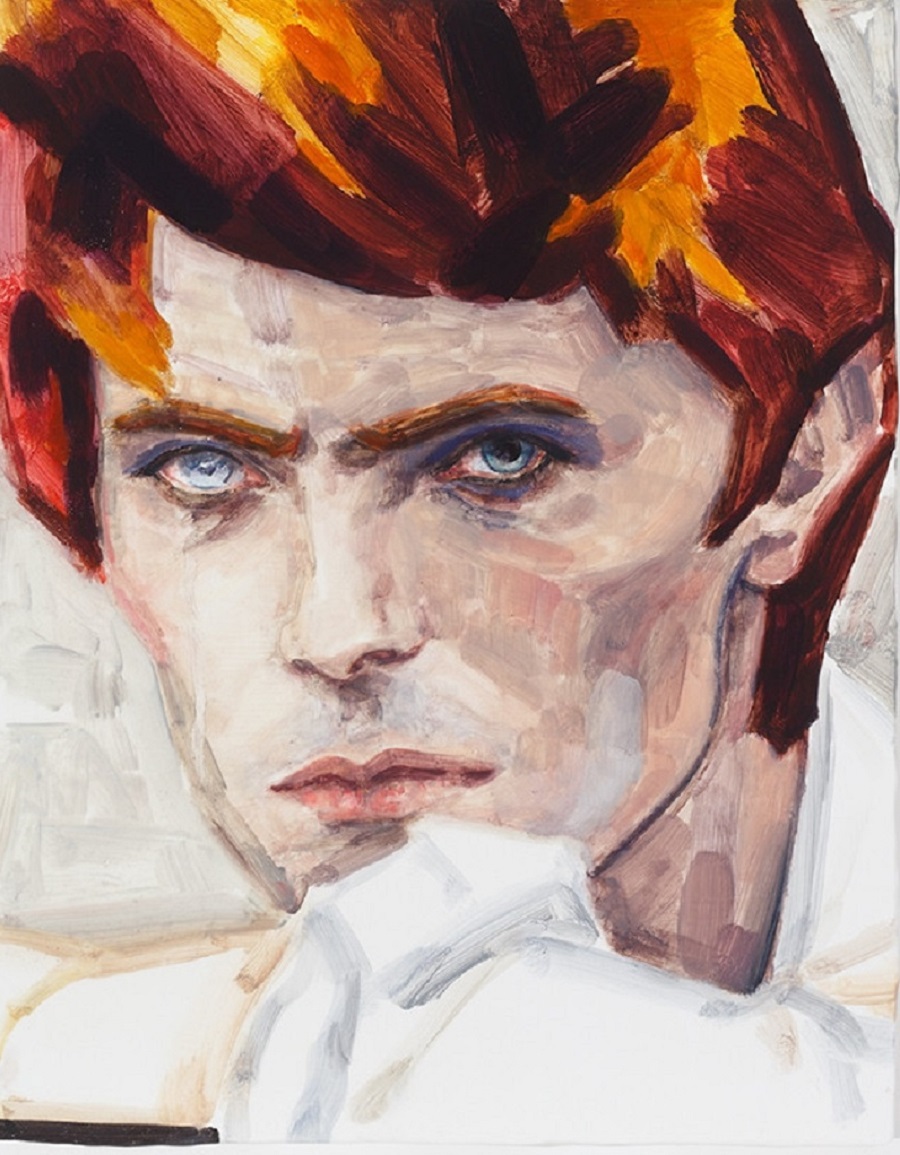

Another factor in her creations is music, especially rock, which inspires and informs the ambience suffusing her portraits. Take, for example, the cover of Suede's compilation album "The Best of Suede". Some of her profiles are of musicians such as Elvis Presley, Kurt Cobain, Pete Doherty, Keith Richards and David Bowie but there are also those of members of European Royal Families including two British princes as young boys.

11th of September (Ben) (2001), available at http://blog.visitlondon.com/

In the nineties, her work could be seen to manifest itself in much paler colours, deft and assured brushstrokes, a sense of the romantic and a more expressive composition. In 2001, she moved to Manhattan where she began working with live models for the first time, rather than magazine or newspaper photographs, and also using a more subdued palette. She fused mood with static objects in her illustrations of this time, using movie scenes and still lifes in, for instance, "Pati" (2007), "Flowers and Diaghilev" (2008), "Houdini" and "Flowers, Lichtenstein, Parsifal" (2009).

Flowers. Lichtenstein, Parsifal, available at https://elizabethpeyton.wordpress.com

Elizabeth Peyton continued to depict personalities from her own social circle as well as more globally famous ones in 2010 and 2011, but with a much more brilliant colour scheme and a more mature, reflective style. Her canvasses can be seen on display in important museums worldwide such as the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Fine Arts in Boston and New York's New Museum, to name but a very few.

Her first ever individual exhibition was at Broadway's Althea Viafora Gallery in 1987 and she has continued to show her art frequently up until the present day. In recent years, she has exhibited along with Jonathan Horowitz at "Secret Life" (London, 2012) in which she showcases still lifes of Nature, bringing together psychology and plants and "Regen Projects" in Los Angeles. In 2013, she presented "Klara" comprising 13 of her works and "Here She Comes Now" in Germany. In 2014, she exhibited "Street posters in The Centre of Arles" at the Vincent Van Gogh Foundation in France.

Live to Ride, available at http://whitney.org/

Klara, available at http://www.glasstire.com/

Elizabeth Peyton does not centre her paintings around beauty stereotypes. Rather, she seeks to validate the person she paints as the means to experiencing beauty in a tangible way, using their image for inspiration but also inviting us to a deeper knowledge that takes us beyond the sublime to a place of absolute beauty. Critics have said of her that: "She chronicles her social circle of artists and musicians; and the suggestive abstractions of O'Keefe."

The artist herself was quoted as saying: "I love everything I do. Working from photographs or "in the flesh" or from memory ... from up close, life has more immediacy, excitement, emotion, as if in freefall, because everything is happening right there and then. Photographs of faces possess a kind of colour saturation and a sense of deterioration you don't find in real life, which I also love."

Irises, available at http://www.artnews.com/

ws-peyton, available at http://painternyc.blogspot.com.es/

David Bowie (2012), available at http://fr.phaidon.com

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum's gallery walls are freshly painted a golden shade of ochre to inaugurate its new exhibition, Zurbarán: A New Perspective (Madrid 9 June - 13 Sept 2015). "Seville's walls, circa 1630, were often of that colour. And, what's more, I think it goes well with the artist's golds and blacks." explains Guillermo Solana, the museum's director and our guide for this tour. A 19th century German philosopher once said that every work of art is "essentially a question, an appeal to the heart that answers it back."and so what we'd like a response to first is: What do Francisco de Zurbarán's paintings mean? What's behind them, those Dominican friars in their white habits, the saints, the martyrs and the vases of flowers? "Zurbarán is, above all else, a painter of the tactile world of volumes and textures." explains Solana.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Detail of St Cassilda's robe. Francisco de Zurbarán (c. 1630-1635)

A conversation with Guillermo Solana

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum's gallery walls are freshly painted a golden shade of ochre to inaugurate its new exhibition, Zurbarán: A New Perspective (Madrid 9 June - 13 Sept 2015). "Seville's walls, circa 1630, were often of that colour. And, what's more, I think it goes well with the artist's golds and blacks." explains Guillermo Solana, the museum's director and our guide for this tour. A 19th century German philosopher once said that every work of art is "essentially a question, an appeal to the heart that answers it back."and so what we'd like a response to first is: What do Francisco de Zurbarán's paintings mean? What's behind them, those Dominican friars in their white habits, the saints, the martyrs and the vases of flowers? "Zurbarán is, above all else, a painter of the tactile world of volumes and textures." explains Solana.

St Apollonia. Francisco de Zurbarán (1636)

St Apollonia. Francisco de Zurbarán (1636)

The entrance to the exhibition is hung with a large map of Seville during the first half of the XVII century. Zurbarán was born in 1598, the same year as the death of Philip II of Spain, and lived until 1664, one year before the death of Philip IV. It's numerical magic. Two great kings who each in their own right made decisive acquisitions and contributions to the royal collections.

Seville, at the onset of the 1600's, was a city of wealth and prosperity, full of convents, parishes, hospitals, an immense cathedral nearing completion ... but also overwhelmed by the heavy burden of the Counter-Reformation, Trento and the havoc wreaked by the plague. "Zurbarán was the painter who best understood the male monastic remit. This kind of painting was too severe and harsh for the taste of female congregations." Zurbarán was the son of a cloth merchant and he replicated those cloths in paint in each of his pictures: their heaviness, the thick folds of the woollen habits, the coarse threads of tablecloths, the stiffly woven Hessian in the Franciscans' sackcloth habits, the green and strawberry-red silk of St Apollonia's gown or the sumptuous brocades worn by other saints, in imitation of the fantastical costumes and ideas being worn on theatre stages or arriving from Venice.

But why then, if this is the case, does Zurbarán's oeuvre focus almost exclusively on painting austere monks and becoming the painter of "monastic life"? Was it for purely commercial reasons? What part did the Counter-Reformation and Trento play in his choices? Solana answers: "Zurbarán understands the key to clarity and post-Tridentate legibility. Trento's instructions were that the language of painting had to be clear, didactic and as far removed from the complications of mannerism as possible. And Zurbarán is indeed 'legible', even in the way he paints chiaroscuro, silhouetting his figures against the light. He is utterly convincing in his expressionism which suits the language of the Counter-Reformation perfectly."

Saint Francis contemplating a skull. Francisco de Zurbarán (1633-1635)

The exhibition comprises 63 of Zurbarán's works, mainly large format, divided over seven rooms. We stop in front of Saint Ambrose, a fine example of what's at the very heart of Zurbarán's painting. Here, the statuesque figure of the Bishop of Milan is outlined by a light coming from the darkness on the left and striking his cape of red and gold damasks and also highlighting a studded mitre of ochre felt. These are the elements that really confer strength onto the picture, far beyond any facial expression, which would have been a novelty at the time. If we think that for El Greco, it was the eyes, the hands and the swirls of angels who conveyed expression and meaning, for Zurbarán it was the "inanimate agents" who speak to us. Solana explains in more detail: "One of the things about Zurbarán that must have fascinated modern artists, such as Manet in Paris for instance, is this egalitarianism in the treatment of figures and objects, in itself one long chapter in 19th century art criticism. One of the things that critics held against Manet and his contemporaries was that they treated the human figure like a thing and things like humans. Traditional academic hierarchical norms were broken down."

Saint Ambrose. Francisco de Zurbarán (1626-1627)

Seville and the power of painting

17th century Seville was, in addition, an important artistic hub with the newly-arrived influence of Caravaggio and Dürer along with German and Dutch engravers serving as the inspiration for many of Zurbarán's scenes and iconographies. And then, above all else, there was Velázquez. In Seville, both painters knew each other well and out of their friendship came Zurbarán's move to Madrid to contribute his Ten Labours of Hercules series to the Hall Of Realms of King Philip IV's Buen Retiro Palace.

We now turn to discussion of the marked differences between Velázquez and Zurbarán and the different languages used by Spain's, arguably, top two Golden Age painters to communicate with their audience. Art Historian Jonathan Brown describes how, while Velázquez viewed his époque through a microscope and portrayed it this way in his paintings, Zurbarán reproduced his world, in his time, as a mirror. In his Portrait of Innocent X, everything is pure expression; the pope's eyes speak, as do Velázquez' brushstrokes. By way of contrast, Zurbarán's Saint Bruno and Pope Urban II are radically different.

Solana concedes but elaborates: "I agree. But perhaps that makes Zurbarán a more modern painter. The Manet or post-Manet schools are less psychological, less interested in expression. Manet's best portraits do not capture or reveal the soul of the sitter. His portraits are, rather, still lifes. Cézanne required his models to pose as if they were apples being painted. The importance of psychological penetration so evident in Velázquez is not present at all in Zurbarán. He was interested in something else entirely."

Still life with pottery and cup. Francisco de Zurbarán (c.1650-1655)

From Zurbarán and Caravaggio to Cézanne and De Chirico.

Zurbarán models with light: his silent monks come out of the dark and dazzle in white. St Serapion is, perhaps, the jewel in the crown of the exhibition. The Mercedarian friar hangs from the ropes that bind his wrists in a quasi-crucified pose. We are familiar with his story of martyrdom, the Jesuits' fourth vote or 'Blood Oath', the acceptance of death, the torment, the ecstasy. Zurbarán hides any traces of the saint's excruciating torture and evisceration under an unblemished habit and there is not the least sign of his violent death to be seen here.

Solana then points out what it is we should be noticing: take, for instance, the Mercedarian scarlet cross emblem against the white chasuble, in the dead centre of the painting. We look around, only to see that same emblem, like a blood stain, in the exact same spot in every other Mercedarian painting in the room.

So we consider for a moment Zurbarán's mode of expression - so subdued, so muted and so inconspicuous. And the difference between his and an Italian contemporary's mode of expression. With Caravaggio, there is a frenzy of gestures, of open arms that seem to reach out of the frame, of hands floating mid-air, of human levitations, of oblique lines and daring composition. There is commotion, action and incident in his The Supper at Emmaus or The Entombment of Christ.

Zurbarán is much more static. Again we consult our expert of the day and Solana indulges us with another master class: "Caravaggio, as a painter, is full of violence, sometimes very intense, sometimes contained but always there, latent. He, as a painter, is full of the instantaneous. There is an explosiveness. In The Calling of St Matthew this is patent. It is replete with what Italians called "Il motto", namely, expression: the body language, a fleeting look on the subject's face ... all givens in early Italian Baroque. Zurbarán's sensitivity is different, calmer, more mystic and less tragic. For this reason, it connects so well with a certain type of 20th century art that avoids excessive gesticulation. That type of art Bernard Berenson dubbed "ineloquent", deliberately and stubbornly silent, Italian metaphysical art. De Chirico, for instance. You mentioned Morandi, too, and rightly so. And then there were all those inter-war painters and their Magic Realism or New Objectivity. To my mind, the ones who connect most closely with Zurbarán are those artists who also suspend their expression for the duration of the silence. From Derain to certain German artists, Christian Schad, Gutiérrez Solana even."

Our next request is for an explanation as to the colour black: that deepest, darkest and most Spanish of blacks. And to understand, also, the way Zurbarán painted shadow. Solana sums it up with: "I believe painters can be divided into those who paint shadows in black and those who don't. From as far back as Delacroix, and then later with Impressionism, we've been told that shadows must be in colour. The great tradition of the colourists was to create shadows that were luminous, transparent, of varying hues. And then there were the painters who said: "Absolutely not. Black shadows, black paint." which probably does produce less sensory charm but also, at times, much more expressive forcefulness. And all of this has a definite link to Zurbarán".

And with this contradiction of black versus white, we leave Zurbarán who, for us, will forever be the painter of the white spectrum. He of the rough peel on quinces and the smoothness of stone, he of the heavy cassocks, of bleak Extremadura landscapes, of what is concrete, of solid volumes, of quiet times and quiet things, of an insurmountable silence that can often lead to a feeling of uneasiness. An exceptional dimension to painting but also one that Cézanne's early still-lifes can boast, or those of Juan Gris and, later still, those of Morandi. But that is another story for another day.

Ignacio Zuloaga, on purchasing one of his paintings, once defined Zurbarán in a letter to an artist friend as: "The Spanish painter. Whereas Velázquez is cosmopolitan and universal, Zurbarán could only ever be Spanish."

St Serapion. Francisco de Zurbarán (1628)

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Luminosity, symmetry and proportion are some of the characteristics of the classical concept of beauty found in the photographs of Candida Höfer (Eberwalde, Germany 1944), to which she adds the existential determination of silence. Her first series in this particular genre depict the ordinary streets of Liverpool and the Turkish communities in Germany and Turkey. From there, Höfer’s work quickly evolved to what are now her most recognizable photographs of the interiors of museums, theaters, libraries, churches, etc., where a stillness that is devoid of time and human presence, and which thus immerses us in silence, also induces the concentration we need to appreciate the spatial vision and beauty of her images. Höfer is a product of the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where she studied photography under Bernd and Hilla Becher, as did other artists such as Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff.

Author: Elena Cué

Candida Höfer. Photo: Elena Cué

Luminosity, symmetry and proportion are some of the characteristics of the classical concept of beauty found in the photographs of Candida Höfer (Eberwalde, Germany 1944), to which she adds the existential determination of silence. Her first series in this particular genre depict the ordinary streets of Liverpool and the Turkish communities in Germany and Turkey. From there, Höfer’s work quickly evolved to what are now her most recognizable photographs of the interiors of museums, theaters, libraries, churches, etc., where a stillness that is devoid of time and human presence, and which thus immerses us in silence, also induces the concentration we need to appreciate the spatial vision and beauty of her images. Höfer is a product of the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where she studied photography under Bernd and Hilla Becher, as did other artists such as Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff. Her photographs of architectural interiors in Europe and America follow the example of the Bechers’ images of industrial exteriors.

Elena Cué: Between 1973 and 1982 you studied at the prestigious Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf where you attended the lectures on photography by Bernd and Hilla Becher. What was the most important teaching you took from that period?

Candida Höfer: Bernd and Hilla's teaching did not come across as teaching in the traditional sense. Both invited us to be open to experiences, to cherish Art in general, not just restricted to photography, to keep our eyes open, to discuss, to remain politically aware.

Does your great interest in architecture also coincide with that period?

In my project about Turkish people living in Germany I had realized that no matter how kindly I was received I felt uncomfortable to intrude. At the same time it was impressive to see how my hosts had created their own environments in their restaurants, shops and living spaces to feel more at home from home. It showed me the importance of the made environment.

In the series you just mentioned, Turks in Germany as well as in Liverpool and Pinball that were some of your first works, you were focusing on portrait photography. Later you abandoned the inclusion of human figures in your works. What did portraits mean to you?

I see my work to some extent as portraits of spaces; this is also why I consider myself not to be an architecture photographer; they would focus on other things.

Candida Höfer. Rudolfplatz Köln I, 1975/ 1999. Aus der Serie Türken in Deutschland. Silbergelatineabzug

What made you abandon black and white photography in order to focus on the use of colour?

I tried color photography and compared the results and found color to provide more for my kind of work.

What meaning does the format add to the message of your works?

I think, with regard to my larger format works light, structures, formal repetitions and variations as characteristics of a space are in the center of my interest. As to the more recent, smaller works I examine these elements in a more abstract way.

Teatro Scientifico Bibiena Mantova I, 2010 © Candida Höfer / VG Bild-Kunst,Bonn 2014.

You combine the two ideal concepts of knowledge and beauty. Would you say you have an unconscious strive for perfection within you? Are you a perfectionist?

... an impatient perfectionist, I am afraid. The large formats need much organization and preparation due to the larger camera format. This is one of the reasons why - while still continuing with my large format projects - I am increasingly now using a hand-held camera for the smaller more abstract works to enjoy the freedom from the restrictions of organization.

The technology available to photographers today is constantly evolving; Do you make use of this progress?

I keep an eye on developments, and I get information. I am not technology averse, but I also feel not technology driven.

In your architectural photographs in which people do not feature, this absence is very present due to the necessity of the relationship between people and culture. Did you do this because you did not want any distraction when contemplating your ideal spaces?

The necessity that you are mentioning gets more visible by absence. What I had started as an approach to avoid bothering people while I am working did turn out as a learning process about the presence of the absent.

In your photographs what is most important: the aesthetic, the technique, the idea...

The image.

What is image for you?

I try to give an answer with my images.

What would you say is your most passional moment in your creative process?

Working with the picture taken to turn that picture into an image.

The prominent motifs of your artistic career are the interior spaces and their functionality and the architecture. What can you tell us about your "Psychology of social architecture"?

I am primarily interested in visual relationships within each singular space and the layers of use visible in that space. If over time my aggregated work contributes to broader insights, then that happens so to speak behind my back.

"Palais Garnier Paris XXXI 2005". CreditCandida Höfer/VG Bild-Kunst, via Sean Kelly Gallery

Your photographs posses social, geographical and historical singularities that endow them with character and contrast against a globalized world. Do you feel nostalgia of perfection in art, of the old aesthetic values, of the aspiration to escape vulgarity...?

I think in front of the photographs in their original size (rather than seeing them in a book) what might come across even in the historically charged spaces is the sincerity and clarity and sometimes also the humor of the space that do not invite nostalgia but just show the strength of the present in the space.

In your series Libraries, what is the importance of books to you as the daughter of a journalist?

Books are not only interesting to read but their physical presence, particularly when they are present in large quantities, their order and variation in colors and form I have always found visually attractive as well.

Your exhibition “ The Space, the Detail, the Image" just opened in Helga de Alvear’s Gallery. Could you tell me about it?

As the title indicates I want to show and set in relation my treatment of large spaces, the smaller, more abstract and detail oriented work and projections under the common denominator "image." My very first gallery work (in Dusseldorf in the 1970s), as you may remember, had been a projection ("Turkish People in Germany"). The projection format has always been of interest to me allowing a dynamization of the image without crossing the border to a - for me at least - distinctly different medium, the film. However, the gallery show will also provide an opportunity to show a film not by me, but about the way I work ("Silent Spaces" by the Portugese director Rui Xavier to be shown at the Circulo de las Bellas Artes on 21 January 2016).

Are you looking forward to your next project? Could you reveal any secrets to us?

Upon invitation from my Mexican gallery, I have just spent three weeks in Mexico and I am now working on the material for museum shows both in Mexico and Germany.

- Interview with Candida Höfer- - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

|

Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Photo from the archives of Svetlana Alexievich

Svetlana Alexievich (1948, The Ukraine) was last year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature on one of the very few occasions it has been awarded for a work of non-fiction or in her native language, Russian. Only Theodor Mommsen, Winston Churchill and Solzhenitsyn have ever been likewise honoured for historical research in prose.

Front covers of the English and Spanish translations of Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel Prize-winning book

It is throughout her book, War’s Unwomanly Face, that the characters’ transcribed voices denounce some of the worst crises of the twentieth century, as experienced by the then Soviet Union: the Second World War, the Afghan conflict, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. Alexievich has invented a new literary genre in which the reader inadvertently comes face to face with gritty truths spoken from the deepest wells of pain in the human soul.

The style of War’s Unwomanly Face is arguably and essentially that of a doctoral thesis documenting the behaviour of Soviet women on and off the battlefield during the Second World War. The book is made up of the not-so-fond reminiscences and short personal stories told to the author by women who risked their lives for their country but were never credited, or even remembered, by history until now. Alexievich remembers how, as a child, she would listen enthralled to the women in her village swap tales about the war. They and their stories had a huge impact on her young mind that only increased over time and led to her wanting to find out more. After moving to Belarus in the late 1960’s to study journalism and forging a highly successful career there, Alexievich embarked on a journey to interview hundreds upon hundreds of women who had served in the Red Army. Those monologues became the initial stages of what would turn out to be a rich and detailed tapestry of testimonials concerning the role and vision of women during this terrible period of time in modern-day history. Women who survived and lived to tell the tale of circumstances so extreme, tragic and painful that it is difficult for us to hear, let alone imagine, them in today’s world. All of these lived experiences, recounted from the most intimate memories of the female protagonists, make up a choral narrative with a unique perspective – what the war to combat a German invasion meant for Russian women at that time and what they understood by patriotism. The author, whilst remaining true to the serious revelations contained in every memory she records, does also grant the reader frequent respite from the severity of her subject matter by the inclusion of seemingly frivolous little anecdotes from the humdrum everyday lives, even during wartime, of otherwise unremarkable human beings. Her prose is concise and without artifice, thereby brilliantly resolving the difficulties inherent in dealing with feelings. It also transmits the author’s empathy with her interviewees who leave us in no doubt as to the veracity of their testimonies and who imbibe the entire book with their palpable strength of will.

World War II female Soviet snipers. Photographer unknown.

The publication in 1985 of War’s Unwomanly Face, written two years earlier, coincided with the welcome arrival of the perestroika/glasnost era and was met with spectacular critical acclaim and commercial success. Its 2015 publication in Spain came in the same year it was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

This is evidently not, therefore, just another book about war or the barbarity of war in our time. It is, rather, a reflexion on the hopes invested in and frustrated by the events that constitute our recent history. When, in 1979, Lyotard described a crisis facing longer novels versus the proliferation of shorter books whose infinite varieties are unforgiving of them, he could have been describing exactly what Alexievich does on a daily basis, namely: she maintains the individual identity of each of her speakers without compromising their credibility or that of the narrative.

For me to recommend that you read it smacks almost of a dare because, as Franz Kafka once said, this is a book that deserves your attention and one that will strike you down with the aim of an ice-pick, chipping away at the coldness in your heart, mind and very spirit itself.

World War II sniper Roza Shanina with her rifle, 1944. Photo by A. N. Fridlyanski

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- “War’s Unwomanly Face”. Svetlana Alexievich - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Detail: St John’s eye. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

It’s 1435 and Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400?-1464) leaves his French birthplace of Tournai, where he had been Robert Campin’s apprentice, to embark on a new life in Brussels along with his Belgian wife and young son Pierre. Here he would paint The Deposition of Christ - now one of the crown jewels in Madrid’s Prado Museum. It is thrilling to see this exquisite painting flanked by the artist’s other masterpieces, in one place for the first and perhaps only time ever, namely the Durán Madonna, the Seven Sacraments triptych from Antwerp and the extraordinary and recently restored Escorial/Scheut Crucifixion.

Flanders: the role of the bourgeoisie in art

Van der Weyden knew that any artistic debate would be settled there in Brussels, a city wallowing in the economic prosperity occasioned by certain dynastic alliances and political stability. Painters, sculptors, illuminators, goldsmiths, tapestry weavers flock to Brussels for its commercial opportunities and potential clientele. The trade guilds start to move and shake within society. Banking and industry are the new sources of wealth, making material comforts and sumptuous lifestyles a reality. The new middle classes are now the catalysts for revolution within both society and artistic parameters. In the “Flemish School” of art they patronise, the object takes centre stage and realism mirrors their enrichment in microscopic detail. The middle classes now require art to reflect their way of life and their high standard of living. Paintings replicate the minutiae of their everyday lives. In the Northern European religious remit, The Annunciation and The Crucifixion are situated inside their very own homes, their gardens, in amongst their furniture, mirrors, pet dogs and shoes, between birds and clouds … and every pearl, every vase and every fireside armchair becomes a chronicle or contains a message. Also, the growing cult and holy grail of fabric perfection: how it drapes and folds; how its colour, texture and quality indicate the wearers’ social status; how textile manufacturing is having its heyday in Flanders.

Shortly after arriving in Brussels and at a pivotal time in his career, Van Der Weyden receives a commission to paint an altar triptych. And it is this work that would mark an end to all that had gone before in Flemish art. ”The best painting in the world”, concluded King Philip II of Spain’s advisors, a sentiment echoed by both their contemporaries and successive generations of experts alike.

Van der Weyden and the Van Eyck brothers constituted two very different camps in Flemish painting. The latter’s mastery of gothic miniaturism produced their meticulous rendering of every detail and their illusory depiction of perspective whilst any emotions, and never any untoward ones, played only a supporting role. Van der Weyden, by contrast, although also a consummate detailist, would be the most ‘dramatic’ of all the Flemish artists. He would outshine all-comers in his composition and his creation of the illusion of movement through linear angling, He fully intends this picture to be a masterpiece showcasing his idea of what painting is and also a new beauty ideal based on the transmission of feelings. The moving beauty of seeing others ‘moved’. All that was then known about painting comes together here in perfect, seemingly alchemic, fusion to flesh and stone, rest and motion, composition and expression, rhythm and geometry. It is also the confirmation of the supremacy of oil as a medium to render the biblical message of Christ’s passion through human compassion, realism and empathy with the emotions of the characters depicted.

Detail: Maria Salomé. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

The journey to Madrid

It was the Grand Guild of Archers, the oldest and wealthiest of the four in 15th century Louvain, who commissioned Van Der Weyden’s work for their chapel - Our Lady Without The Walls. As a homage to and marker of their patronage, there are two small crossbows hung on the spandrels of the tracery in the top lateral corners of the painting.

Detail: Tracery with hanging crossbow. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

In 1548, the painting was acquired by the Emperor Charles’ sister, Queen Mary of Hungary, in exchange for a copy painted by Michiel Coxcie and an organ worth 1,500 florins. Mary, also governor regent of the Netherlands, hung the painting in the chapel of her castle at Binche with is fine collection of the very best paintings and tapestries, its frescoed walls and ceilings and its jasper fireplaces, all handpicked by the queen herself. It was seen and admired there in 1549 by her nephew, prince Philip of Spain, and his entourage. By 1556, the painting had been gifted to him, now King Philip II, and was hung first in the El Pardo palace and later in the sacristy of the El Escorial monastery fortress alongside Van Der Weyden’s Scheut Crucifixion. In 1939, it was moved to the Prado Museum where it remains to this day.

Baltic Oak and Flemish Oils

Recently arrived with his wife and small son Pierre, Van Der Weyden has a large house in the silversmith neighbourhood of Brussels out of which he starts work on The Deposition, not as yet having a separate workshop of his own. Given the ongoing influence of traditional altarpieces, Van der Weyden and his two assistants carefully select the boards of wood to be used, rejecting any with knots or imperfections and positioning them vertically in the direction of the grain. The support for the painting would eventually comprise eleven panels of the best Baltic oak.

Back in his studio, the painstaking task of priming the assembled panels begins: one layer of stucco and gelatine size, laboriously hand polished to give an impeccably white, marble-like surface. It is by this process that oils of that era achieved such luminosity: transparent upper layers of colour traversed by the white base underneath them. Often the top coat applied was of a lead-filled white with enormous reflective qualities.

Detail: The clothing of Nicodemus and Mary Magdalene. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

Van der Weyden paints with a palette and brushes; it’s the moment of revolution in oil in Flanders. This technique has been known and used since antiquity and up the 15th century when the Van Eyck brothers perfected it by mixing pigment with a linseed and walnut oil substance. They also added a quick-dry agent that also enhanced the oils’ fluidity, thereby solving the two great problem defects in the technique up until that time. One of the characteristics of oil, compared with tempera’s opaque egg and pigment combination, was its fabulous transparency that afforded a hitherto unknown depth. Van der Weyden exhaustively explores the possibilities of the technique: veiling and superimposing colours to reveal objects as never before; a tear’s reflection, shoe buckles set in the shiny surface of a stone. VDR also sought out the highest quality pigments for this piece. For this reason the painting emits a lustre normally only seen in varnish or enamel. From a technical point of view, The Deposition is one of the most elaborate and well-preserved works of its day. Rarely has a colouring been seen so vivid as that of the Virgin Mary’s apparel, resembling rather a flame of blue fire than a coat of paint. Transparency favours colour saturation, which in this case was achieved with a base layer of greenish blue superimposed with two layers of ultramarine.

Detail: The Virgin Mary’s clothing. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

Dramatis Personae of the tragedy

Much has been written about the sensation one experiences on viewing this painting from a certain distance. It’s theatrical staging, as if the curtain had just been raised in a small village theatre of the time. The tableau vivant that would be so familiar to the imaginations of people of that era, accustomed as they were to seeing representations of Eucharistic plays.

The size of the figures, and, more importantly, their positioning in a composition where time seems to be standing still. They are characters immersed in the drama taking place around them, shown in their gestures and expressions, and must have been in total motion before the curtain went up. Arms opening, hands joining, crossing and falling. The ladder cutting through the cross, the pliers to remove the crucifixion nails, the Virgin Mary in mid-fall to the ground, Christ’s body and its weight against Joseph’s chest. The behaviour of the characters, the heightened expressions, the eyes, reddened but still intently focused, mouths half-open, the theatricality and the central role of emotion and its expression during the whole gamut of stages of grief: anxiety, mourning, weeping, self-restraint, tears, fainting. Nothing crass or gruesome or sensational has any place in this painting.

Christ’s body is treated with supreme delicacy. It is the otherwise unblemished body of a young Jewish man, the only pathos to be found is in his petrified facial expression and the marble-like colour of death on his skin.

There are ten in this cast of characters, six on the left and four on the right. They make up a geometric design of straight, horizontal and oblique lines, bracketed and closed off at the sides by the curved bodies of Mary Magdalene and St John. The rhythm of the painting, undulating, uneven, irregular, full of puzzles to be solved, of eyes or lines of vision or patterns telling us where we should be looking is one of the painting’s fascinations for us.

The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

And there is much of the sculptural about the painting. Van der Weyden, who survived the Black Death raging in his native Tournai in 1400, was heavily influenced by the funereal statues and carvings he saw growing up. It is also supposed that his apprenticeship with Robert Campin began with instruction in sculpture and this early influence never left him.

Two principal forms traverse the scene diagonally: that of Christ having been lowered down from the cross and that of the Virgin Mary who has just fainted. The shape of these two bodies as they descend in a synchronised echo of each other, one beside but below the other, is that of two crossbows. In perhaps another nod to his patrons, the arms of Christ and his mother each form their own semi-circular arc whilst the trunks of their bodies form the straight stock of the weapon.

To the right of Christ and dressed in an opulent coat of purple and gold damask, Nicodemus’ fixed gaze takes us across the oval of the painting from above. Along the radius emanating from Christ’s right hand, it takes us over Christ’s loincloth to one of the most iconic parts of the painting: the hands of the Virgin Mary and her son’s falling limply within centimetres of each other and about to touch. The diagonal line stops abruptly here and we find ourselves contemplating a few square inches of paint that make this one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art. One hand is punctured by an open wound, the blood congealed into rolling tear shapes, against a backdrop of green velvety damask and red stockings; the other is alone, its fingers softly and slightly spread against a backdrop of lapis lazuli. A genius excerpt from a painting that transcends time itself.

Detail: The hands of the Virgin Mary and of Christ. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

But the story continued and so does the diagonal line, as far as the feet of St John: “Woman, behold your son …” (John 19, 25 – 27) and Mary’s other hand that lies inert, upturned and grey on the ground next to the skull of the first man God ever created, Adam.

Detail: The right hand of the Virgin Mary and the skull of Adam. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

This diagonal line that traverses the painting, like a ray of lightening, delineates the message that Man’s redemption after Adam and Eve’s original sin is here in the death and resurrection of Jesus. And in the compassion of Mary, her co-passion, her sharing in and of her son’s suffering. For us all.

Christ’s body here shows no signs of the flagellation he endured before they crucified him. All we see are the nail wounds to his hands and feet and where he was stabbed in his side. This latter wound between his ribs is palpably deep. The crown on His head is a hideous braid of greyish green rosebush thorns still painfully driven into his forehead and left ear.

Detail: The body of Christ. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

Christ’s neck twists to the side, disjointed, lifeless. His mouth is half open and we can see the bottom edge of his top teeth. As a general rule, in scenes of this type, Christ is fully bearded. Here we see only stubble, perhaps what has grown over the three days it took for him to die on the cross. The blood from his pierced side had dripped down as far as his inner thigh under the loincloth, but cleanly, without staining it. Like a red ribbon seen through sheer muslin.

Detail: The Virgin Mary. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

The Virgin Mary’s head and décolleté are covered by the exact same white frilly-edged fabric as Christ’s loincloth and Mary Magdalene’s scarf. This white contrasts sharply with the lilac of her lips, the washed-out pink of her eyes as they roll backwards and the pallor of her skin after she swoons. Five tears trickle down her face, one about to drop off her pale chin.

She is dressed in a tunic. The cloak that fell to the ground as she fainted is edged with gold thread and covers her elongated legs and all but the tips of her splayed shoes. This blue stain flooding the centre of the painting flows backwards towards the ladder and the cross like a river of soft waves.

Joseph of Arimathea, the rich man in whose tomb Jesus’ body would be laid, wears a tunic of purple black, edged with fur that, like his beard, has been painstakingly applied, one hair at a time, individually. Van Der Weyden’s lushly beautiful technique carries over into the red tabard, its border beset with pearls, rubies and sapphires, each a precious jewel in itself. Above Joseph’s head is the cross, in the form of Tau and of such tiny, unreal proportions that Christ’s extended arms could never have been nailed there.

Leaning on the crossbeam and literally squeezed inside the frame, the young manservant of Nicodemus or Joseph holds in his right hand the pliers that have only just extracted the nails from Christ’s palms.

To the left of the Virgin Mary are three figures: Maria Salomé, a young woman dressed in green, and supporting the Virgin Mary with her hands. Van der Weyden paints her face as almost identical to that of the Virgin Mary beneath. Are they perhaps sisters? Maria Salomé’s head and part of her body are covered by heavy, olive-green velvet, tied under her breasts with chord and tucked under her right elbow, allowing us to see the fur lining, matching the collar and cuffs, and her under dress of the same tone but this time shining and embossed with patterns and motifs.

Detail: From l to r: Mary Cleophas, St John and Maria Salomé. The Deposition of Christ, Rogier Van Der Weyden

To her left is St John the Apostle, youngish and barefoot, as was customary in most Christian iconography. His left foot treads on the Virgin Mary’s cloak as he lunges to soften her fall. His cheeks and eyelids are reddened, wrinkled and swollen with tears. Although his eyes continue to stream with emotion, his face is set in a numb expression of absolute sadness and sorrow. The pigment used for his crimson tunic was made from one of the most expensive ingredients available – kermes dye, extracted from the dried red bodies of female scale insects.

Facing diagonally forward, Mary Cleophas fills the upper left corner of the niche outside the central oval. Partially hidden behind the hunched semi-circular figure of St John, her grey apparel continues on the monochrome blocks of primary colours surrounding her and culminates in a cascade of white folds and pleats covering her whole head and neck and held in place with a small pin at the top. Mary Cleophas is of mature age. The whole psychological burden weighing down on her is concentrated in her hand gestures. With her left, she clutches a dark blue cloak across her chest, the little finger alone oddly protruding straight out from her clenched fist for reasons known only to he who decided to paint it that way. Her right hand, with a wedding ring on its middle finger, dabs at her brimming, semi-closed eyes with the scrunched tip of her headdress. A full seven tears in what is essentially only part of an obscured partial profile.

Detail of Mary Cleophas. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

To the right of Christ’s prone body and holding his legs is Nicodemus, a rich Pharisee known for bringing myrrh and aloe for the embalming before burial. He wears a black, pointed hood and clothing identical to that of Jan Van Eyck’s Chancellor Rollin in the Louvre painting: a doublet of velvet damask in purple and gold edged with fur. There existed at that time a hierarchy of cloths and colours. At the Bourgogne court, the highest echelon wore gold threaded garments, whilst the rung below wore gold braid, then satin print, followed by damask and finally plain silk. Colours also had a status: gold first, then crimson with a little black, followed by black with a little crimson.

Behind Nicodemus stands a bearded servant dressed in green and cradling a white ceramic jar with the embalming perfumes in his right hand. His left hand, thrust between his master and Mary Magdalene, as if to separate them, creates a foreshortening to the verism, albeit hesitantly.

And lastly, the figure of Mary Magdalene whose emotionally charged presence closes the painting to the right. She embodies the tragedy of having witnessed the death of he who had saved her from public execution for adultery by daring her persecutors: “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone”. Her elbows raised high and her fingers tightly clasped under her chin in a gesture of prayer, her purple cape slipped off, exposing her bare décolleté, the trauma evident in her pose leads us to believe she is about to fall at the feet of Christ, those same feet she had once so lovingly anointed with oil and dried with her own hair, and that are now bloodied and dead.

Her dress also is a lesson in the fashion of the day: sleeves were normally worn short so she has tacked on a longer, red velvet pair with a small metal pin. The hem of her green dress is edged with thick velvet and her hips balance an ornate girdle belt that spells out the letters IHESVS MARIA. The buckle consists of two metal ovals tied with a long chain.

Strong light fills this part of the painting from above right and illuminates the exposed skin of Mary Magdalene’s vulnerable back and neck. But one’s mind’s eye is drawn back again to the mysterious belt and what its significance might be.

Inside the Golden Box

The ultra-modern style in which Van der Weyden painted his figures and their expressions contrasts sharply with the unreal and anachronistic frame he sets them in. It’s a crowded horror scene squeezed inside a lantern or gold trinket box and recalling the reliefs of antiquity. An old instinctive reflex from the artist’s sculptor training of the past? Or is it, rather, his natural tendency to pit the two against each other in order that the supremacy of painting shines through?

And why does Van der Weyden, a highly accomplished painter of skies and landscapes, renounce them both in favour of a background more reminiscent of a Byzantine icon?

The scene is set against a golden wall which, unlike contemporary flat-roofed altarpieces, has here an added section jutting upwards and outwards from the body of the painting. The two corners are decorated with false Gothic tracery of gold painted wood. The gold leaf applied over the base primer has black on black specks, blended with reds and applied copiously in order to create light and shade and give the impression of a deep perspective.

Detail: Mary Magdalene. The Deposition of Christ. Rogier Van der Weyden.

This sublime painting, staggering as much for its details as for its colours, its technique, its composition and its drama, recalls Ingres’ words: “Details perform an essential role in classical painting – to engage the spectator as they contemplate them is to touch their soul.”

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

-Tears in Van der Weyden's Deposition of Christ - -Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Hiroshi Sugimo's portrait. Courtesy of the artist.

The Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto (1948), is a photographer that resides halfway between Tokyo and New York. He received various awards: The Hasselblad Foundation International Award (2001), The Imperial Award (2009), The Purple Ribbon Medal of Honor (2010), The Officier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2013) and the Isamu Noguchi Award (2014).

If anything distinguishes Sugimoto's black and white photographs is its use of natural light, the shadows and the purity of forms, some close to pictoric. Standing in front of many of them, the spectator is encouraged not only to look but also to think; as in his noted marine landscapes, its immutability causes loosing the notion of time. They invite to a constant reflection about the origin and history of the world and of our culture, where concepts like space and time are explored expanding our ways of perception.

Without further ado we begin our conversation in his austere New York studio. Large windows fill with light his office presided by two photographs: Duchamp's bicycle wheel and one of his theaters.

Elena Cué: The seascape picture I just saw in the entrance reminded me of the exhibition you presented in London (in 2012) along with Rothko's paintings from 1969, a year before his suicide, was very interesting. This photographs induce us to meditation...

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Yes, the people spent quite some time in front of my seascapes and I found some kind of similar sensitivity with the Rothko paintings. That is why I put them together. Especially the final years of Rothko - they’re very monochrome and very abstract - and they echoed my special night seascapes.

Adriatic Sea, Gargano 1990. Courtesy of the artist

I remembered how your photographs gained in beauty once their protective glass was removed. They looked just like paintings.

Yes, but they have the price of photographs!

Is Eastern spirituality implicit in your work?

I don’t care whether it’s Eastern spirituality or Western spirituality… There is a spirituality.

You don’t require labels?

Well for marketing, it reaches a wider audience if I don’t use ‘Eastern’ or ‘Western’ spirituality!

Your In Praise of Shadows series is directly reminiscent of Tanizaki. What is the enigma of shadow for you?

I live in the shadow… I like shadow, that’s why I became a black and white photographer. The quality of the shadow says something. And the quality of the shadow is something that I can control… the tonality of darkness to light. Black and white photography is the best medium to show this.

Which kind of light do you prefer to use?

Natural light, of course.

What do you think of the current aesthetic of light, someone like yourself who belongs to a millenary civilization that is antithetical to Western civilization?

Well, Tanizaki complains about modern society with its artificial light. Since humans invented artificial light, our lifestyle has changed. Especially with electric power. With candlelight, there was a more human-friendly atmosphere. Then all of a sudden we have nuclear power and electricity… so then we changed to nightlife. It used to be nice and intimate, and somehow it was the poetic quality of nightlife that we all lost. There is a beneficial side to it, but not that side. We lost so much, instead of gaining some kind of benefit.

Now that we have discussed light, let's turn to emptiness and loneliness. Why, in your Theaters series, is the lighted stage empty?

They look empty but they are full of information. They have accumulated the information of many millions of small photographs that a movie consists of. Before the invention of movies was the invention of photography. To make a movie, you have to sew single-shot photographic images together to make it look like a movie. It is all an illusion to the human eye. So there are many pictures within the white. It’s not empty, it’s too crowded!

Hiroshi Sugimoto. El Capitan, Hollywood, 1993, gelatin silver print, courtesy l’artista

Your work constantly evokes primitive scenes. How important for you is that infancy of the world?

I feel like I’m a stone-age man. I try to go back to the original roots of our mind, of our consciousness, that maybe we lost many thousands years ago – or maybe only fifty or one hundred years ago. The human mentality was somehow different. That’s what Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows is telling us. Again, this is modern societys' negative side and positive side. That’s what I’m trying to save, before it is completely lost.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. Wapiti 1980. Courtesy of the artist

With such beautifully dramatized light as yours (your use of chiaroscuro), to what extent would you say you are a pictorialist?

Pictorialism was a very interesting phenomenon in the late nineteenth century, after photography was invented. Many painters changed their profession to photography. But twenty or thirty years later, there was a fight back from the painter’s side. Also, it was asked whether photography could be art or not. The camera is a machine and the machine has no spirit. So photography makes machine-made paintings. Photographers developed some sort of complex against painters. So the photographer tried to imitate the painter, which is where pictorialism entered photography history. I don’t have any complex, but I’m still trying to be a painter.

Was there a period when you painted?

Well yes, I painted when I was in High School.

But you decided not to continue...

It wasn’t that I couldn’t paint and instead decided to become a photographer; I can still paint, but photography was a new medium for me. So when I was young, I thought that photography held more possibilities for the future, to be used as a new kind of tool to create new art. Painting is one of the oldest mediums in art for the human being. People have tried many different things and there’s too much competition. I wonder whether I could be better than Picasso – that’s the question!

We have already touched upon the exhibition that you recently presented with Mark Rothko in London. You have said that he helped you on your path to abstraction via photography. Could you tell me about that experience?

Well, to compare myself with Rothko is a brave act! I had a sense that we might share some kind of similar mentality or spirituality. Don’t think about the market price; I cannot compete with him! So that was something to almost surprise people with photography and painting’s relationship. What is trying to be represented? That kind of abstract spirit can be shared with the photographic method. And in a sense, I think it was a success. One of my next projects in the near future will show Impressionist paintings together with my seascapes. Because I knew that Monet painted seascapes in Étretat, in Northern France, so I went there and I found the spot where Monet must have painted them. I took the seascape photographs from the same point. Not the landscapes, only the seascapes.

How beautiful!, so this will be your next project. Where will it exhibited?

It is not decided yet, but I am working on it now.

Any future projects in Spain?

In February I will be at Fundación Mapfre in Barcelona. Then in June I’ll be at Mapfre in Madrid, which will be a retrospective.

So that will be a very important exhibition for you.

Yes, it will be my first retrospective in a museum in Spain. Afterwards, it will travel to Brazil in South America.

But you did visit Spain before, I recall your traditional Japanese puppet theatre: The Love Suicides at Sonezaki. What does Bunraku mean to you?

I’m moving more into the performing arts, especially the traditional Japanese performing arts. So bunraku is the one that I’m doing now. I’m trying to remake traditional theatre. Sometimes, the way they perform is not the way that it used to be. The production is from the 18th Century, so I’m always trying to get back to the original spirit. For my production, the lighting especially is not so bright. I have to use artificial light of course, but I’m trying to create an atmosphere of pre-modern traditional theatres. This sense also derives from the kind of quality found in In Praise of Shadows.

Wasn't your father also involved in theatre?

Yes, a different kind of art form - traditional storytelling at the Comédie-Française. Old stories with lots of jokes.

He must have had some influence on you…

My cynical mentality comes from my father!

And what did you receive from your mother?

My mother was a very good businesswoman, a very well balanced person. She was spiritual I think… religious, even. For a long time, she was a Christian. She was sent to a missionary school in her childhood.

And did this change you at all?