- Details

- Written by Kilian Lavernia

At first glance, the work of Marina Abramović (Belgrade, 1946) would appear to conform to that hackneyed old saying that the best art is always about the self. However, as with so many other clichés about contemporary art, this serves only to limit the scope, richness and originality of this particular artist who, since day one over four decades ago, has made her own human body into a vital space for experimentation, her raw materials and a battlefield, even. Abramović herself is, effectively, the work itself. But only in as much as one must then incorporate this variable into a more complex equation, after pioneering reflection on the ultimate meaning of her performances which, after forty years of creative exploration, has consolidated her place and her identity within postmodern discourse.

Photo portrait of Marina Abramović by David Leyes

At first glance, the work of Marina Abramović (Belgrade, 1946) would appear to conform to that hackneyed old saying that the best art is always about the self. However, as with so many other clichés about contemporary art, this serves only to limit the scope, richness and originality of this particular artist who, since day one over four decades ago, has made her own human body into a vital space for experimentation, her raw materials and a battlefield, even.

Photo portrait of Marina Abramović. Image available at www.cronicasyversiones.com

Abramović herself is, effectively, the work itself. But only in as much as one must then incorporate this variable into a more complex equation, after pioneering reflection on the ultimate meaning of her performances which, after forty years of creative exploration, has consolidated her place and her identity within postmodern discourse. As a form of visual art, of art as action, her performances are both experiments in trying to identify and transgress limits of control over one's own body as well as, in regard to the relationship between public and performer, searching questions about the taxonomic boundaries in traditional art, based on the divide that exists between these two: subject and object. If we understand her body as simultaneously both subject and medium, Abramović's experimental probing breaks away from the ideas of stasis and temporality inherent in our usual aesthetic understanding, and thereby expands the dialogical, structural boundaries of any piece of art.

Still from A House with the Ocean View (2002). Image available at vimeo.com/72468884

The Serbian artist's performances involve an immediate and emotional exchange of energy with the public, as she intends, making them that last piece of the equation without which the transformative experience of art would be incomplete and in vain. On this matter, she has commented: "I could never give a private performance at home because I have no audience there [...] The bigger the audience, the better the performance and the more energy runs through the space. The audience should take an historic step and really connect with the object."

The artist is present (2010). Image available from the Marina Abramović Institute website: www.mai.art

From the very beginning, Abramović's output has been daring, provocative and transgressive. She began her artistic studies in the mid 60's in her birthplace of Belgrade, continued and finished them in Croatia, returning to teach Fine Art in Serbia in 1973. Ever since her debut with the well-known Rhythm (1973/74) series, framed as a bold, hazardous exploration of Body Art, the young Abramović was testing, on one hand, the body's limits in the face of physical pain, suffering, self-harm and, on the other, the moral resistance of the public to feel her world through those very personal experiences of her female body. It was a work in, on and of her body.

Rhythm 2 (1974). Image available at marinaabramovic.blogspot.com

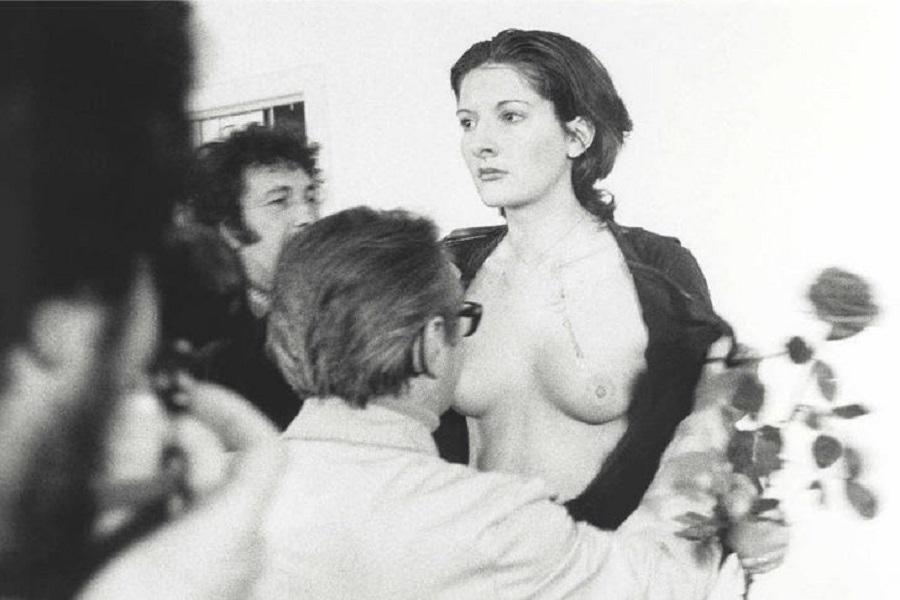

The different variations of Rhythm used embodiment to reflect on universal themes such as death, pain, sorrow, time, the limits of consciousness and unconsciousness, not to mention the behavioural patterns of the mind. Likewise, in Rhythm 2, she experimented with the varying states of lucidity and loss of corporal control produced by the ingestion of a range of different pills. In Rhythm 0, one of her most emblematic performances, Abramović literally put herself at the public's disposition. Along with 72 different instruments of different uses - from pencil to polaroid camera to perfume as well as knives, whips, chains and a loaded gun - she offered up her body for a no-holds-barred, unscripted, interactive show with her public.

Rythm 0. Image available at www.upsocl.com

The visitors were invited to choose any object and use it on her in whichever way seemed most interesting to them. And so began what was intended as a reflection on trust and the social contract and ended up being a palpable demonstration of Man's natural inclination towards violence. "What I learnt was that, if you allow the public to decide, they could kill you. I felt really attacked: they cut my clothes off, they scraped rose thorns across my stomach, one person held the gun to my head before another took it off him." Abramović's silence and lack of reaction meant that the violence escalated quickly and dramatically. "After exactly six hours, as planned I got up and started walking towards the public. They all scarpered, avoiding a real-life confrontation."

Rhythm 0 (1974). Image available at ourpursuitofart.blogspot.com

The subsequent evolution in Abramović's work owes much to her character trait of inclusivity and her willingness to be ever open to others. In a certain way, it's in her nature to have infinite possibilities. As opposed to the unitary and bourgeois concept of one single artistic identity, namely the definition of the artist-individual focused on each work as a solitary project, Abramović invariably challenges herself to build up emotional interactions with second parties and with herself as producer/director.

Proof of this came at the end of the 70's when her artistic output centred around an unclassifiable dual manifestation of her art in productive and emotional conjunction with her lover, the German artist and photographer Uwe Laysiepen, better known as Ulay. In a series entitled The Other, Abramović and Ulay performed numerous performance works as a duo in which their bodies – always synchronised, dressed (or undressed) identically and with similar behavioural patterns – created additional ways in which to interact with the public. Based on a professional and sentimental relationship of absolute trust, both liked to speak of an "adrogynous unity" whose actions personified the limits of interpersonal relationships, their effect on the "I", the ego and artistic personae. This is perfectly illustrated in Relation in Time (1977), one of their earliest joint perfomances, where this hermaphroditic union is symbolised by their tightly interwoven hair.

Relation in Time (1977). Image available at pomeranz-collection.com

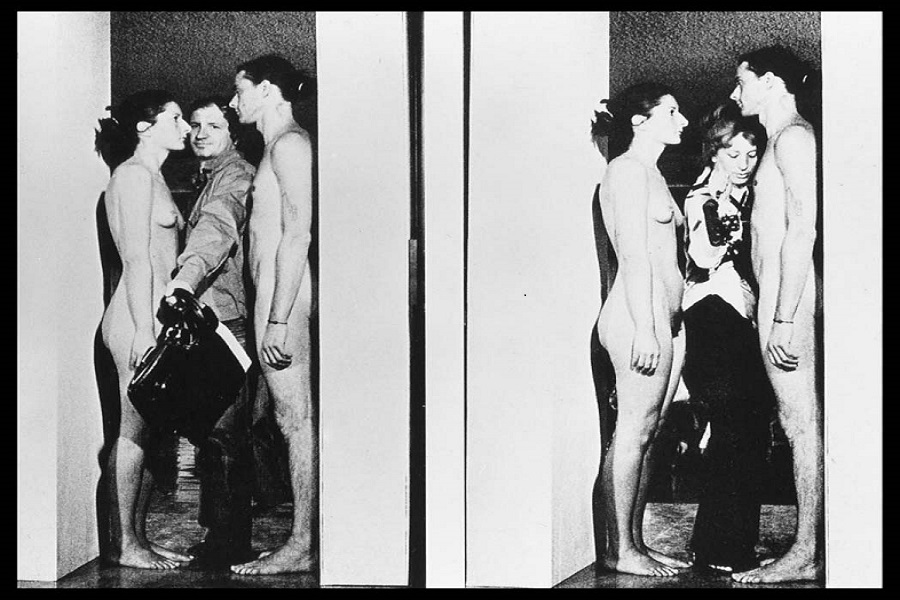

Their collaboration produced further and riskier (and indeed risqué) projects such as Imponderabilia (1977), where Abramović and Ulay stood facing each other, completely unclothed, in a narrow passageway at the entrance to the museum, thereby obliging visitors to squeeze between them and brush up against their naked bodies.

Imponderabilia (1977).Image available at delir-arte.blogspot.com

Another equally compelling joint performance was A-AAA (1978) where both artists shouted at each other in a firm-handed show of power designed to determine who had the more dominant voice. Better known is Rest Energy (1980) in which the couple faced each other, stock still for hours, holding a bow between them and the arrow between Ulay's fingers aimed directly at Abramović's heart. The strength and stamina required of both of them to maintain tension and prevent the arrow being shot was palpable. During the whole performance, microphones recorded both their heartbeats, both of them accelerated and agitated, a clear manifestation of a state of vulnerability in which responsibility and control could slip from their fingers any second.

Rest Energy (1980). Image available at www.altrevelocita.it

The "The Other" series, as much a passionate romance as an artistic collaboration, had as its symbolic finale the famous staging of 1988's The Lovers. Here too, their emotional and professional rupture was played out as a work of art, portayed as a hike, each on their own, departing from opposite ends of the Great Wall Of China until meeting up again in the middle. A three month long and lonely walk culminating in one last embrace. It is an almost definitive physical and communicational goodbye - it would be 23 years until they saw each other again - and an attempt to stage the disintegration of their relationship by means of the physical and emotional fatique occasioned by a 2,000 km journey on foot. It could in some ways be called a romantic ending: unclassifiable, unorthodox and emotionally charged with mysticism.

The Lovers (1988). Image available at http://inkultmagazine.com

With hindsight, Abramović's subsequent reinvention of herself as a solo artist could be defined as the crucial turning point in her career. A certain time lapse and, more importantly, long-distance travels abroad, Brasil for instance, led to a creative resurgence during the 90's that broke away, once and for all, from the conscious assumption that her life and her art would be inseparable from and fundamental to all her future productions. And so, although the body would continue to play an undeniable part, the performances evolved into spaces destined for the liberation of her own personal demons, underlying or otherwise, as well as new forms of performing as a way to explore how we relate to reality.

An illustrative example, from the early 90's, would be the object installations she herself defined under the umbrella term of Transitory Objects. By incorporating natural materials such as semi-precious stones, bones and magnets into her actions, Abramović wasn't looking to give them a function of their own, as if they were sculptures. Rather, she was using them to generate experiences and energies, as if they were everyday life rituals. One has only to remember, from the initial stages of this second phase 1990 - 1994, the Dragon Head series in which the artist sat stock still whilst various ravenous pythons, who hadn't eaten for two weeks, slithered all over her body. It's an image of potent mythic-feminine resonance.

Recreation: Dragon Head (2010). Image available at mai.art

Even more striking, given the eponymous violence of the time, was Balkan Baroque (1997) which won the Gold Lion award at the Venice Biennale that same year, the Festival's highest prize. Expanding on the theme of the human skeleton, previously explored in Cleaning the Mirror (1995), Abramović used video installation to recreate the putrifying horror of armed conflict in the Balkans War. As well as projecting an image of her own parents on the walls, the artist positioned herself in the middle of the space, washing a huge pile of 1500 raw, bloodied veal bones whilst singing traditional folk songs from her childhood. The dramatic staging no doubt owed a lot to the conceptual baroque of her design but also lent it sincere and credible political weight.

Balkan Baroque (1997). Image available at www.tropism.it

Abramović's recognition as an artist has been irrefutable since the turn of the century. Whilst, on the one hand, it is true that her active participation in various works has become so minimal as to be almost the mere fact of her being there, life and art for Abramović are intertwined as if an absolute presence, as if frozen in time. It is from this angle that she seeks to lift the public's spirit, not so much via direct emotional shock, performance surprise or Brechtian compromise but rather through other more energy-giving mechanisms such as silence, meditation and ecstasy-like consciousness: "To create a type of artwork that is almost devoid of content but still retains a kind of pure energy that will left the spectator's spirit", is how she described it in a 2008 Klaus Biesenbach interview.

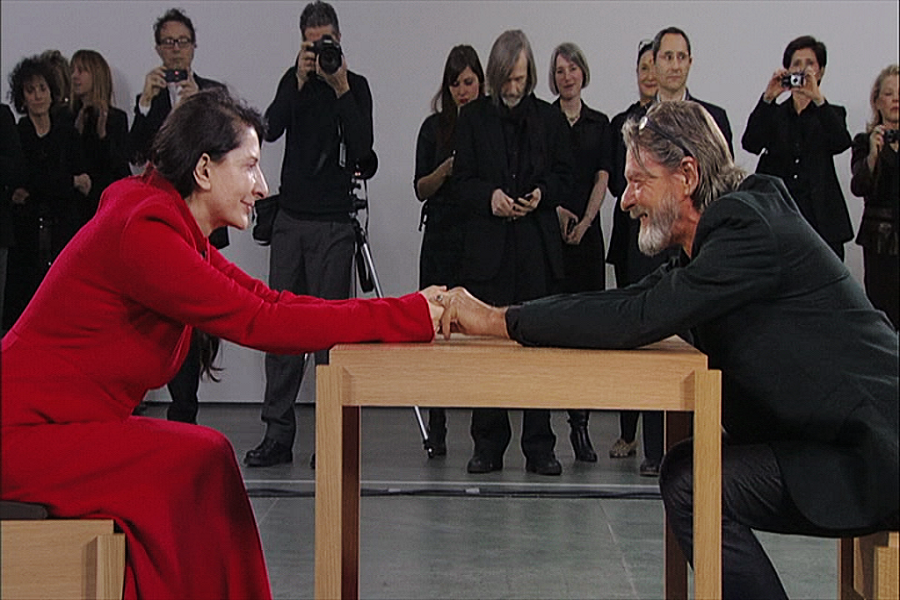

In this regard, one inevitably thinks of the unforgettable The artist is present, an exhausting performance piece presented in March 2010 on the occasion of a MoMa retrospective of her entire back catalogue which remains, to date, the most important ever and, with more than 50 exhibit pieces including performances, installations, videos, photographs and collaborations along with the subsequent documentary of the same name. For three whole months, Abramović remained seated in the lobby of the New York museum for over 700 hours (during opening hours and without a break) allowing over 1,800 visitors, each in turn, one by one, to sit opposite her in total silence, separtated by just a table, and to share the imperturbable presence of the artist for as long as they considered necessary.

The artist is present (2010). Image available at www.filmswelike.com

Like a challenge to time, like a reflection on modern-day society's emotional alienation, the hit piece created an immediate connection between artist and spectator - no verbal communication necessary - and made the lack of communication between one fragile body with another, especially in a great metropolis like New York, even more palpable.

There were also moments of utter surprise: after 23 years of separation, Ulay appeared out of the blue on the day of the inauguration. Abramović's heart visibly missed a beat on seeing him and he was the only one with whom she had any physical contact, after a brief conversation using only their eyes.

The artist is present (2010), reunion with Ulay. Image available at www.visualnews.com

But at the same time, it is no less true that diversification of format and method have been a constant in Marina Abramović's life and works, aware as she is of the increasingly global reach of what she has to offer and say. One need look no further than her much-lauded collaboration with Robert Wilson in the experimental opera The Life and Death of Marina Abramović which delved into the idea of her life's (and various deaths') leitmotifs as its narrative, with other great artists like Antony, Willem Dafoe and Wilson himself joing forces.

Marina Abramović and Antony in The Life and Death of Marina Abramović. Image available at www.robertwilson.com

As a final thought, one might ask oneself if, by focusing her most recent efforts on constant meta-reflection and revision of her prolific output, the potency of her artistic message has seen itself somewhat compromised by a worldwide success that has, unavoidably, transformed the scope, meaning and impact of her performances. Can those same concepts and themes of 20 or 30 years ago still be conveyed today? Given recent changes in the way artists communicate to us and the media and spaces now available to them, would it not be, rather, a case of qualitatively distinct experiences?

Slow-motion workshop, directed at the Whitworth Galley, Manchester (2009). Image available at passengerart.com

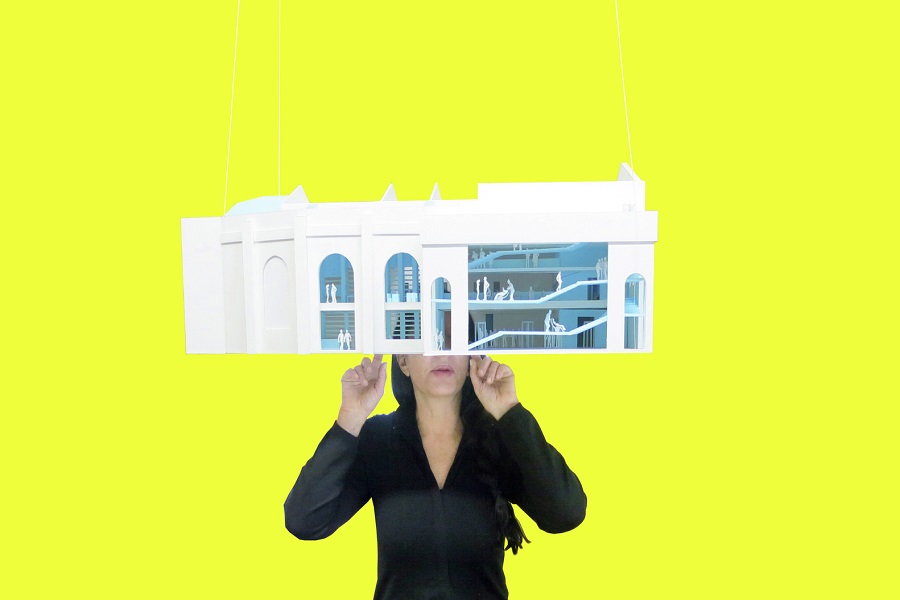

Art as action, live art made with the artists' own bodies is an artform belonging to a tradition predating but not predicting the digital age that came with all its short-lived sensations and hyperinformation. Neither did it anticipate a scenario of absolute trivialisation or the lionisation of those other anonymous performers of the 21st century, on youtube for instance. In any case, the conventional definition of performance as 'action that happens within a limited time frame' is in urgent need of revision. Perhaps the Marina Abramović Institue (MAI), inaugurated in 2015 in New York State, might take it upon itself to gather together a multidisciplinary think-tank to review it and instruct places of collaborative and experimental art in society today with the Serbian artist's legacy as a starting point. The "grandmother of perfomance", just turned 70, has a lot of life left in her yet.

Publicity campaign for the Marina Abramovic Institute. Image available at mai.art

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Marina Abramovic: Biography, works and exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marisa Carrero

Jasper Johns was a small-town boy from the Deep South whose university art teacher urged and convinced him to move to New York. He had known he wanted to be a painter from the age of five and was to become one of the most influential American painters of the second half of the twentieth century.Born in Augusta, Georgia in 1930 and raised in Allendale, South Carolina, Johns' childhood love of painting lead him to study art; first at the University of South Carolina from 1946 to 1947, and later in the Parsons School of Design in New York in 1948, where his work was first exhibited. His artistic career was interrupted by two years of military service in the Korean War, part of which he spent in Japan. Upon returning to New York in 1952, Johns worked in bookshops for a few years while he familiarised himself with the city’s art scene.

Jasper Johns was a small-town boy from the Deep South whose university art teacher urged and convinced him to move to New York. He had known he wanted to be a painter from the age of five and was to become one of the most influential American painters of the second half of the twentieth century.

Jasper Johns. Image available at newsoftheartworld.com

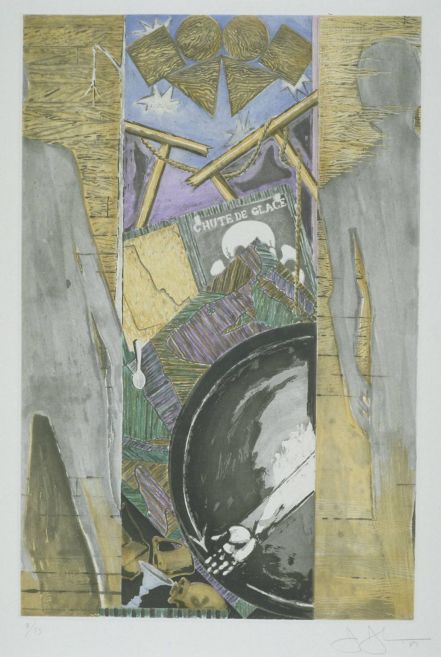

Born in Augusta, Georgia in 1930 and raised in Allendale, South Carolina, Johns' childhood love of painting lead him to study art; first at the University of South Carolina from 1946 to 1947, and later in the Parsons School of Design in New York in 1948, where his work was first exhibited. His artistic career was interrupted by two years of military service in the Korean War, part of which he spent in Japan. Upon returning to New York in 1952, Johns worked in bookshops for a few years while he familiarised himself with the city’s art scene. The friendships he struck up there with artists such as the musician John Cage and the choreographer Merce Cunningham were to have a big influence on his understanding of art. The painter Robert Rauschenberg, a fellow exponent of abstract expressionism in the 1950s, was especially influential; although Johns would later make a complete departure from that movement and go on to create new styles. A visit to Pennsylvania to view Marcel Duchamp's The Large Glass had a huge impact on his artistic vision. With his readymades, Duchamp had invented a new creative method of transforming found objects into art. The influence of this work would lead Johns to incorporate objects such as rulers, spoons and coat hangers into his paintings.

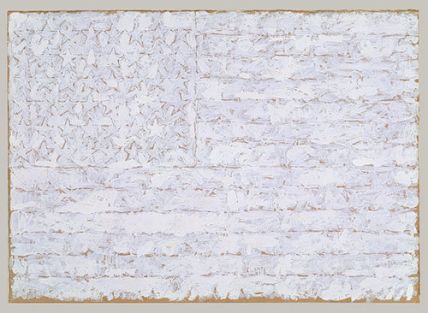

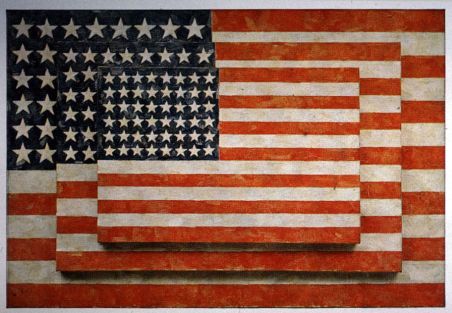

Left: Flag. Image available at www.metmuseum.org Right: Three flags. Image available at www.usc.edu

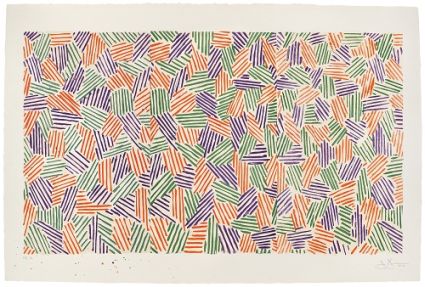

In 1954-55 he made his famous Flags, works which were hugely influential on 20th century American iconography. The paintings Flag, Target and Numbers formed part of his first great solo show at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. Made using the 'encaustic' technique (in which pigment is mixed with hot wax and applied to the canvas), the flag paintings were revolutionary in their apparent simplicity and power. The show made such an impact that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York bought three of the works to exhibit in its gallery. Jasper Johns had taken a giant step forward by incorporating the everyday imagery of North American life into his work, taking “things the mind already knows” as his subject. More interested in the creative process than the work itself, Johns did not restrict himself to one single style but used diverse methods such as lithography and screen printing. At this point in his career he moved away from his roots in abstract expressionism towards new styles such as pop art, minimalism and conceptual art, which many credit him with having helped to invent. He began to incorporate objects into his paintings, transforming them into sculptures and creating original collages from the results.

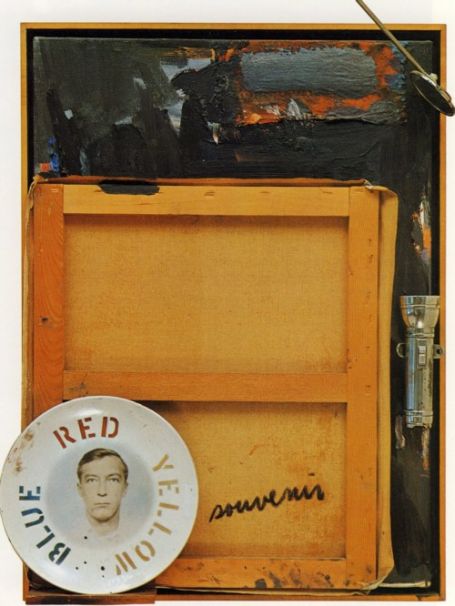

Left: Souvenir 2. Image available at www.artchive.com

Right: Recent Still Life. Image available at www.ulae.com

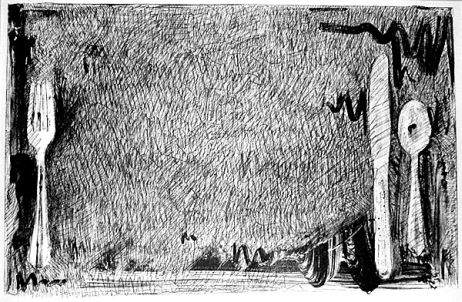

During the 1970s, he collaborated with many artists of the day, such as Andy Warhol, Robert Morris and Bruce Naumann. These collaborations helped to further his career and allowed him to continue his artistic studies and research. During this period Johns took on new perspectives and created new art forms, such as his illustrations for Frank O'Hara's book of ‘poem-paintings’, In Memory Of My Feelings. In 1964 he made one of his most famous prints, Ale Cans; an image of two cans of Ballantine Ale which he had previously made as a bronze sculpture in 1960. He searched for different ways of seeing and representing the same objects through a variety of disciplines, including printmaking, sculpture and even photography.

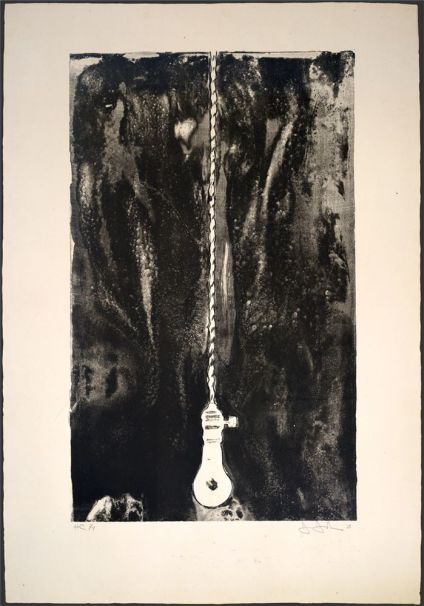

Left: In Memory of My Feelings. Image available at greg.org

Right: Two Ale Cans. Image available at www.theartsdesk.com

For some of Johns’ followers and students, the seventies marked a transition over to a more autobiographical style that was quite different from his early work. He paid homage to Cezanne and Picasso; dividing his paintings into various panels and creating works full of primary colours, such as Scent (1973-74) and the triptych Weeping Woman (1975). In this period he seemed obsessed with repetition and he remade images using a variety of artistic techniques and mediums. He made his friend John Cage’s aphorism his own: “if you do something more than once you get better results”. For Johns it was a matter of searching for the similarities and differences between the various representations that he created. Following a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, Johns’ work was exhibited in galleries across Europe, including the 1978 Venice Biennale exhibition, and a show of 'working proofs' at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, among others.

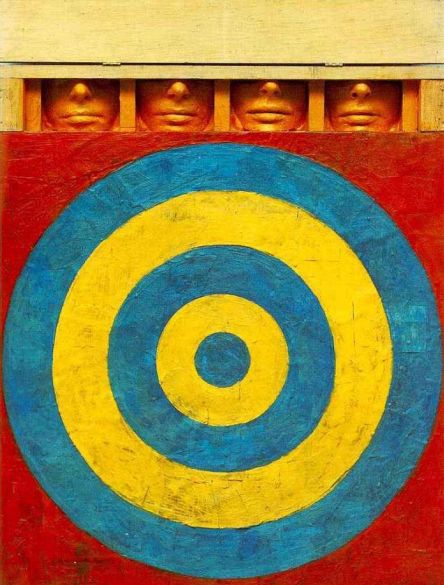

Left: Target With Four Faces. Image available at www.jasper-johns.org

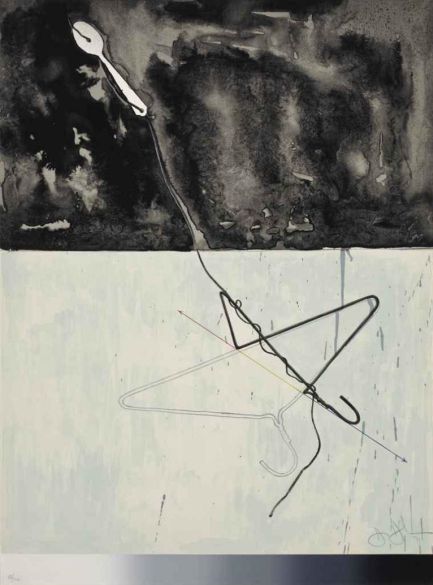

Right: Coat Hanger and Spoon. Image available at www.christies.com

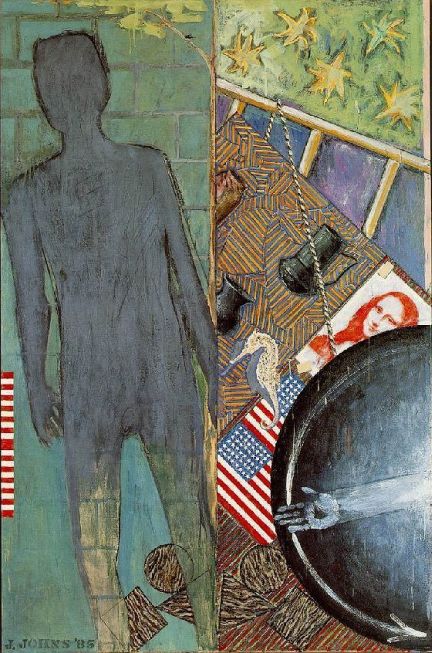

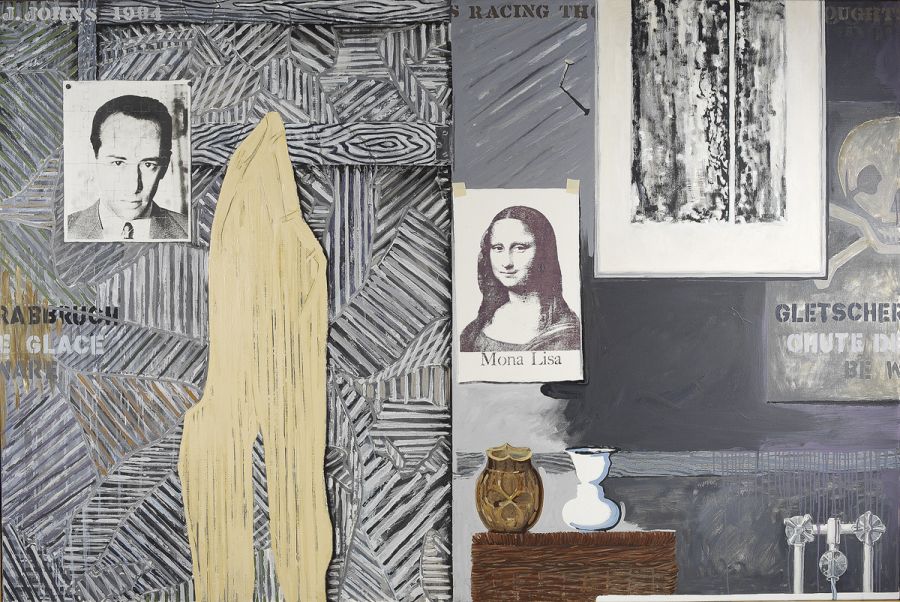

Johns’ work would change direction once again, as he experimented with innovative art forms and began a new creative cycle. For the 1987 exhibition The Seasons at the MoMA, Johns created a series of paintings called Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter which included human figures. That same year, the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid hosted one of the most important retrospective shows of his career, featuring 180 works from 1960-1985. The show was curated by Riva Castleman, the director of the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books at the MoMA.

His work began to fetch incredible prices at auction, making Johns the most sought-after living artist of the day. However, throughout all of the experimentation and changes in style over his career, he never stopped creating. Nor did he ever abandon his love for the colour grey, as demonstrated in paintings such as Bridge (1997), Catenary (I call to the Grave) (1998) and Near the Lagoon (2003), in which he suspended strings across almost completely grey canvasses. His work returned to Spain in 2011 with a new retrospective exhibition organised by the Valencia Institute of Modern Art, which included the first public showing of a ‘New Sculpture’ he had made four years earlier.

Left: Fall. Image available at dexedrina.blogspot.com.es

Right: Summer. Image available at www.jasper-johns.org

Famously, Johns said that “to be an artist you have to give up everything, including the desire to be a good artist”. Perhaps this explains the continuous shifts he made in his artistic trajectory; a restless man who constantly reinvented his style. Yet aside from this, his great power is evident in the overwhelming influence of his work on the following generations. He remains one of the most world’s most valuable living artists, whose work fetches astronomical prices at auction.

Even today at the age of 86, Johns continues to be news in the art world, as demonstrated by the success of his 2014 exhibition at the MoMA in New York, Regrets. This series of paintings, drawings and prints created during the previous year and a half were all based on a single photograph of the artist Lucian Freud, taken in 1964.

Left: Untitled. Image available at www.theartsdesk.com

Right: In Memory. Image available at www.spaightwoodgalleries.com

Johns once said that his work was “largely concerned with relations between seeing and knowing, seeing and saying, seeing and believing”. Throughout his entire career he has seen, known and created using almost every type of material and technique (including lithography, screen-printing, engraving and sculpture), producing a unique body of work and forging a movement of his own within the art world. For the next generation of artists that follow in his wake, Jasper Johns remains one of the great masters of the 20th century.

Above: Racing Thoughts. Image available at www.nj.com 7 February 2008

Left: Jasper Johns. Image available at drawpaintprint.tumblr.com

Right: Catenary. Image available at visualarts.walkerart.org

Left, above: Scent. Image available at www.artnet.com

Right, above: Homenage to Jasper Johns. Image available at www.tapestry.co.nz

0-9. Image available at www.jasper-johns.org

Translated from the Spanish by Ben Riddick

- Jasper Johns. Biografía, obras y exposiciones - - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Crossing the threshold into the London home of the musician, composer and visual artist José María Cano, one enters into a sensorial experience. I let the music floating from the second floor guide me to a room where his son Dani was immersed in playing the piano while José María sang Donizetti´s “Ah mes amis”. My presence in no way interrupted their symbiosis, and if anything I was lured into its flow. The scene brought me back to the heights of music José María had reached years ago with the band Mecano, and reminded me of the lyric drama of his opera Luna. Passing by the many works of art that scattered around his home, part of a magnificent collection he has put together over the years, we went into his studio, where surrounded by his own works —his La Tauromaquia and portraits, lining the floor and walls— the artist invited me to begin my interview.

Author: Elena Cué

José María Cano. Photo: Elena Cué

Crossing the threshold into the London home of the musician, composer and visual artist José María Cano, one enters into a sensorial experience. I let the music floating from the second floor guide me to a room where his son Dani was immersed in playing the piano while José María sang Donizetti´s “Ah mes amis”. My presence in no way interrupted their symbiosis, and if anything I was lured into its flow. The scene brought me back to the heights of music José María had reached years ago with the band Mecano, and reminded me of the lyric drama of his opera Luna.

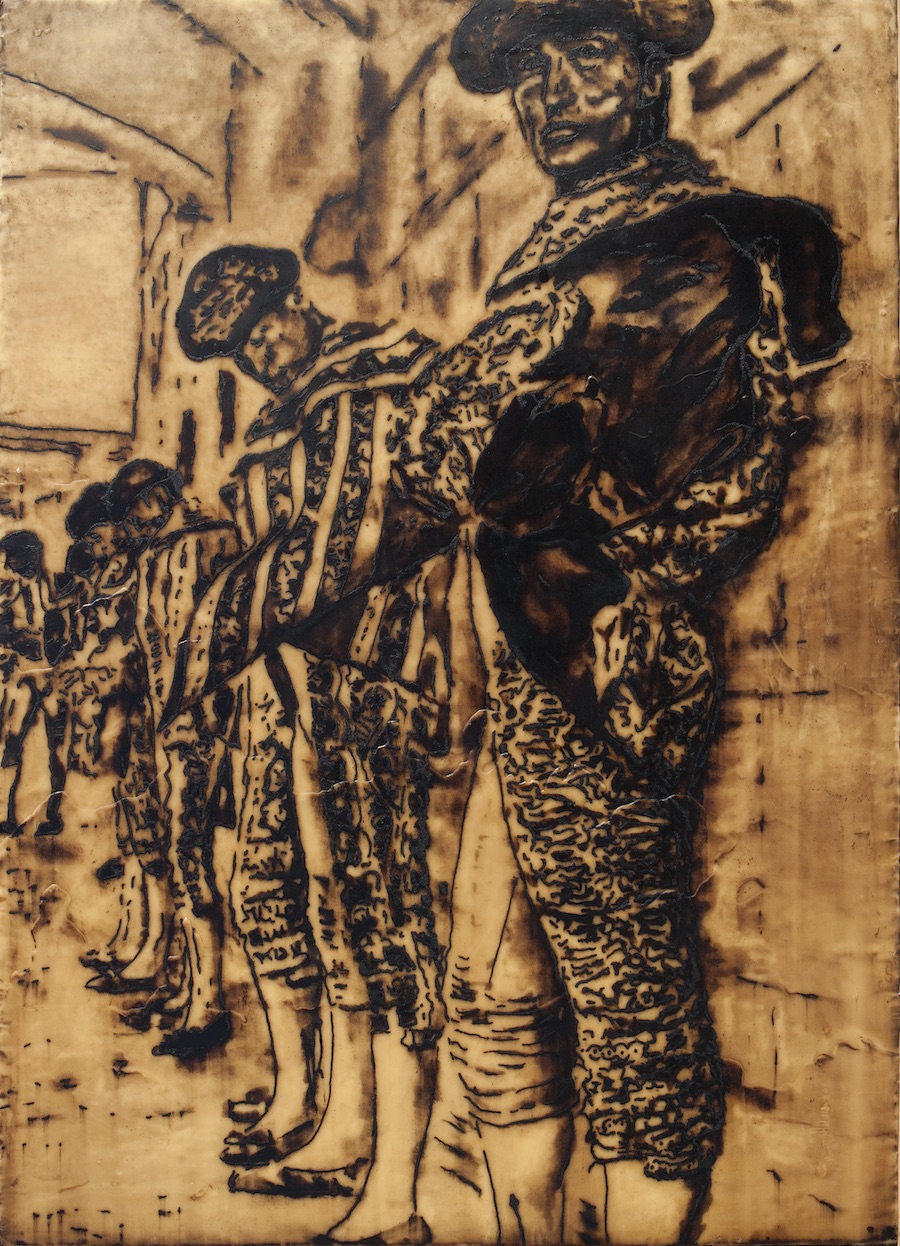

Passing by the many works of art that scattered around his home, part of a magnificent collection he has put together over the years, we went into his studio, where surrounded by his own works —his La Tauromaquia and portraits, lining the floor and walls— the artist invited me to begin my interview.

E.C.: You’ve just had an exhibition at the CAFA Art Museum in Beijing; 200 works gathered under the title Differences and Similarities between Reality and Truth. Tell me about that big show.

José María Cano: I was very pleased with it. Until then, museums had mainly exhibited my wax paintings concerned with economic issues, but that’s only half of my discourse. I felt that knowledge of my work had become lopsided; whereas this exhibition gave balance to its conceptual dichotomy. It’s not that my work has two distinct sides to it, but rather that I paint duality.

E.C.: Is that why you chose this title for the exhibition?

José María Cano: Yes, that’s right. The show was a retrospective of fifteen years of my work. The title, which some people find misleading, is actually the leitmotif of my painting. To my mind, the juxtaposition of the real and the truthful shapes is what carves us out as human beings. My paintings, which on the surface seem to offer a varied materialization, always walk that rickety line. Like when I was a kid. Climbing up to where nobody climbs, to see the world from there. Following the sun, and then the moon, and then the sun again, and only stopping if there was no moon. There’s nothing more seductive to me than the moon in summer or the sun in winter. With eyes opened or shut.

E.C.: Anyone listening to you would think that you live a very relaxed life, when clearly that’s not the case…

José María Cano: But they wouldn’t be completely wrong, in that I work by expression. More than work, I use the John and frame the result. Like Manzoni’s Artist’s shit cans. Even wax, which I like for my painting, is the excrement of bees.

E.C.: It’s true that you move between two almost opposite worlds. On the one hand, there are your paintings on your divorce papers, newspapers or the economy, and on the other, you paintings of a more spiritual nature, such as your series of apostles or paintings about the moon. “Between the sky and the ground,” as your song said.

José María Cano: This borderline way of seeing life lets me paint works from both banks of the same river. On one shore I get my clothes dirty and on the other I wash them. Human beings are a mix of matter and spirit which in the past were in constant, grueling struggle with each other. That battle drove and gave meaning to civilization. Read the poem by Lope de Vega “¿Qué tengo yo, que mi amistad procuras?” (“What have I that my friendship you should seek?”). We’ve now solved the problem by excising from ourselves the spiritual part. Living like that may be easier, but it ain’t worth a dime. Plus, it’s not impossible, with age and a little self-deprecation, to harmonize these two worlds within our selves. But works of art are forced to essentialize. I move steadily from the spiritual to the material, like a mason who stacks layers of brick and mortar, and then wipes away the excess with a trowel.

Wall Street 100 instalation. Beijing Museum. José María Cano.

E.C.: Do you think this view fits in to the current discourse of contemporary art?

José María Cano: No. Today’s art demands provocation, politics, total uniformity or hollowness for it to be of interest to its zoilists and many beneficiaries which, incidentally, include me. My painting lacks these four characteristics. So I won´t deny that my path is a solitary one. Luckily, my gallery is for snipers. Guess that’s why its name is Riflemaker.

E.C.: Your last exhibition was during the Frieze Art Fair Week. Why do you think that your gallery chose to show your work in such a desired week?

José María Cano: You’d have to ask them, but Tot Taylor has said that he values the technique and beauty of my work, and that it is atemporal and without shame. I’m glad that’s what he thinks, because he definitely doesn’t have any either.

Far side of the moon. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: I saw the catalog. You exhibited paintings of the moon…

José María Cano: Small encaustic paintings. I was told that it was the most talked-about exhibition in the press during Frieze. For instance, it was chosen as the show-of-the-week by the magazine The Week. The gallery had to extend its hours, and the works were acquired by museums and important private collections. This couldn´t have happened at other galleries, not with such subtle work. My moons were very happy there.

E.C. (reciting a verse from a song written by Cano and performed by Mecano) Hijo de la Luna... Parece que la luna le persiguiese donde quiera que vaya [Child of the Moon… It seems that the moon follows you wherever you go].

José María Cano: That song began with “a fool he who doesn’t understand”. From the ground, the moon is symbolic in character. There being two universes, this one is symbolic. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been fascinated by the works of Torres García. The moon is a clear indication of the visual dimension of the universe, and of the spiritual dimension of man. It is the recipient of humanity in its entirety’s most beautiful gazes, both living and dead. Sometimes we forget that most of humanity is dead, but it is; in the craters of the moon’s hidden face, perhaps.

E.C.: First a musician and then a painter, and successful as both. Which of these two arts do you think best transmits feelings and thought?

José María Cano: They’re complementary realms. I think that lyrics compel the listener towards a specific feeling. The visual arts are an open proposal to the observer. I like to listen, but I like to touch just as much, and especially to see. To touch things that attract my attention. And to observe them in detail. My paintings have an obscene tactility and I love it when people touch them.

E.C.: You use different media such as oil, resin, encaustic and pigments mixed with different binders. Why do you choose these materials over others?

José María Cano: I’m an alchemist in that “what I paint with” not only determines “how I paint” but also “what I paint” and consequently “what I feel”. The truth is that I paint with anything that lasts. The contrived search for originality is both the great discovery and the great evil of twentieth-century art. Fortunately, it seems like that whole antiquated debate, which is all it ended up being, is on its way out this century.

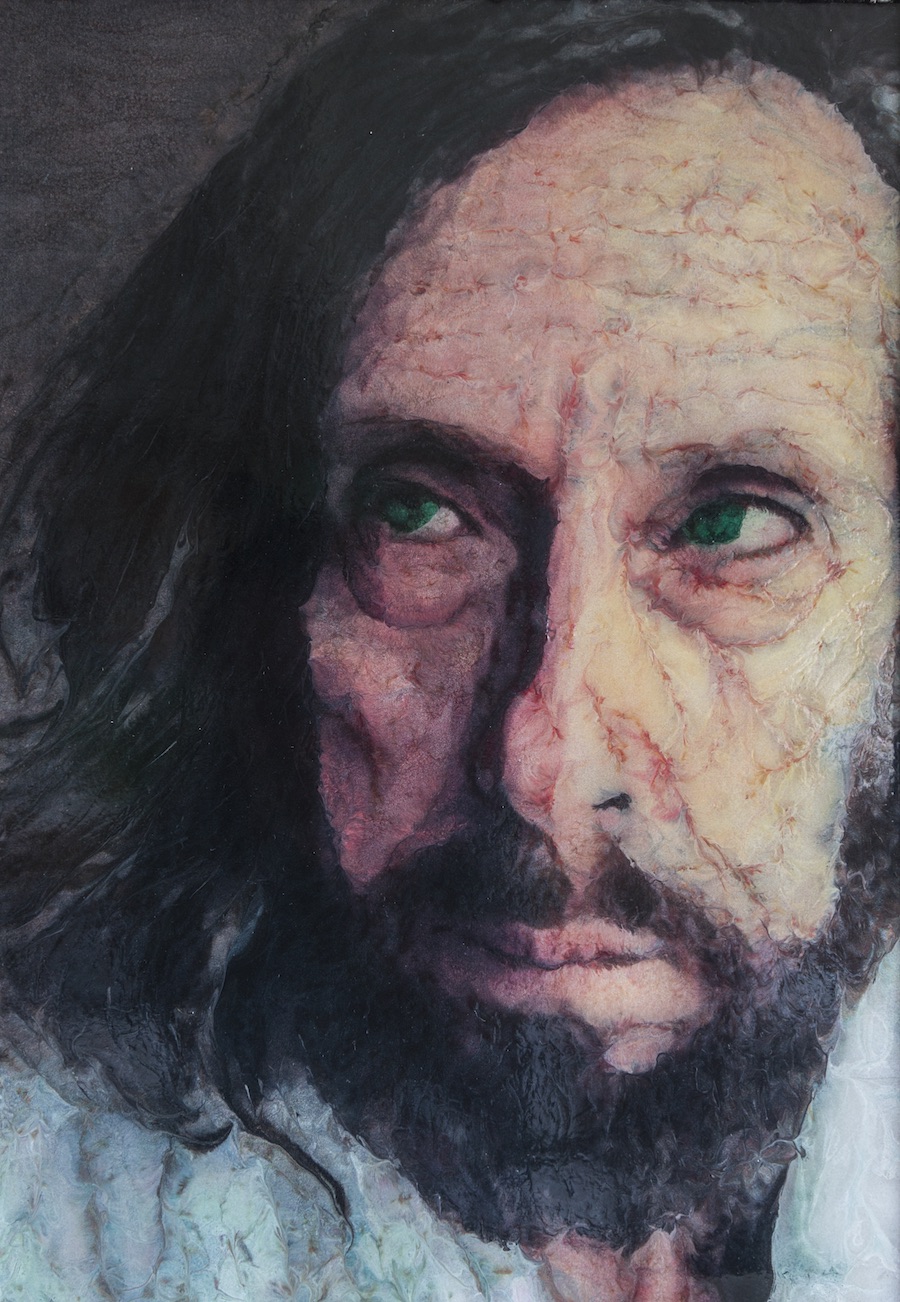

Saint James Bourneges. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: How did your years studying architecture influence your knack for drawing and painting?

José María Cano: More influential were my school years, prior to University. I went to a Jesuit school. Mr. Paz, the school’s photographer and drawing teacher, encouraged me to attend the Hidalgo de Caviedes academy. Up until then, I hadn´t ever seen a nude woman, not even in a photograph. I swear. And we were almost all guys. Once a week, a model would come and unfurl her anatomy. Very “neoclassical —but really, just plump. There were several of them, all well fed. It revved up our drawing. The reddish light of the furnace lent the scene a certain je-ne-sais-quoi. So, in this mix of hormones and graphite, I learned to draw, happy as a clam.

E.C.: Your close-up portraits strike me as very British, very School of London. Have you been influenced by your 25 years living in London?

José María Cano: I do see them as English, but going back further. To me, they are closer to Van Dyck than to Bacon, Auerbach or Freud. In fact, in their portraits, those painters showed a strong desire for originality that I don´t have. Quite the opposite. My portraits seek the timelessness of the upward gaze. Of spiritual questioning. Of physical peace. If there was something that I looked at as I worked on my apostles, it was the studies of male heads by Van Dyck, who lived in London but was Spanish, like me.

E.C.: You are very well versed in contemporary art and the social structure that supports it. What were your criteria in putting together your art collection?

José María Cano: I don´t consider myself an art collector. In fact, ever since I began painting professionally I stopped buying paintings by other artists. I like paintings as objects, and I like to live surrounded by them. But I don´t feel a sense of ownership towards them, nor much so for the works I paint.

E.C.: In your work, you focus on current affairs such as the defense of human rights, capitalism, prostitution... The titles of your shows at DOX Prague and PAN Naples were Welcome to capitalism and Arrivederci capitalism, respectively. Do you use your art as protest?

José María Cano: I’m not one to protest. Or complain. I began to paint as the leader of a movement with only follower —me— that I called materialismo matérico. That was the title of my exhibition at CAC Malaga. First I painted my divorce papers, and followed that with other works of a chrematistic nature. Figures of the financial world as they appeared in the Wall Street Journal, company financial statistics from the Financial Times, etc. But not as protest. I accepted these figures as the new beauty, ironically. And as an artist, as is customary, I felt compelled to pay tribute to such beauty by reproducing and magnifying it.

La Mirada. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: You’ve made a series of bulls, a very Spanish theme. How important are your roots to you?

José María Cano: My series of bulls is actually called De providentia and addresses the relationship of man to his destiny. It´s the title of a letter from Seneca to his disciple Julius, in response to his question of why bad things can happen to good people. Seneca answers that this only appears to happen. That water and oil don’t mix and that these challenges are opportunities for the brave man to demonstrate his greatness. In my ring, the bull represents mankind and the bullfighter, destiny. The right way to face destiny is not to hook into it and lift it off its feet. It’s to bravely charge right at it. And patience, of course, because the bad thing about providence is that it’s fricking slow.

José María Cano Apostolate Paintings of the Apostles San Diego Museum of Art with Spanish Golden Age

José María Cano. photo: Elena Cué

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

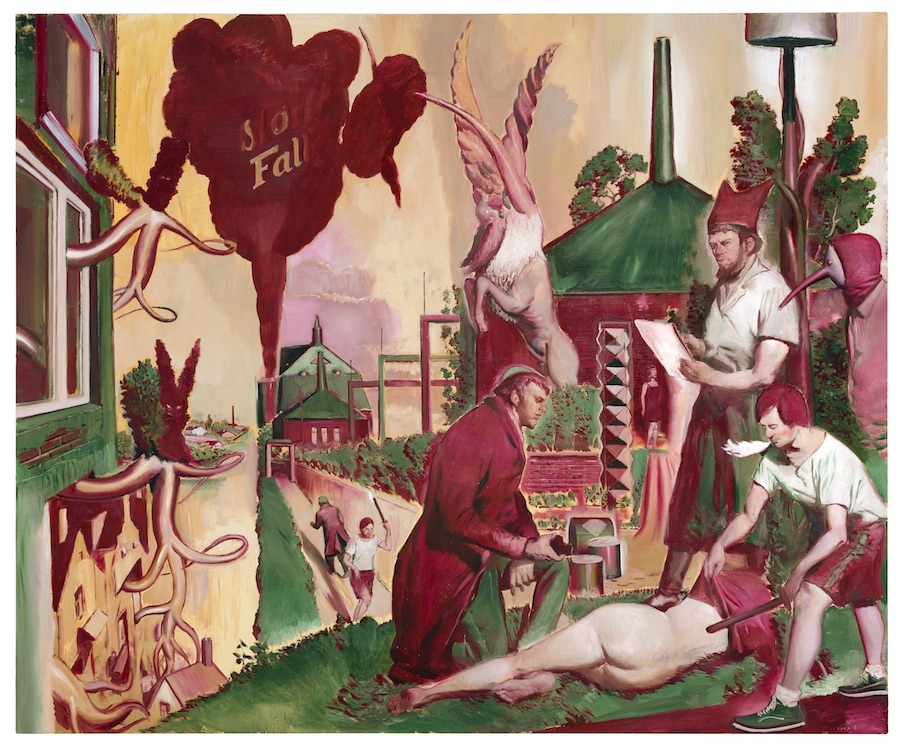

All that lies behind our thoughts ends up ruling our existence as silent forces. Those deepest, darkest places are not easy to penetrate, but if we are attentive to the signs we produce, we can decipher and understand a bit better what we are made of. The dreamlike imagery in the works of Neo Rauch (Leipzig, Germany, 1960) is laden with symbolism: the overlapping of apparently unconnected scenes, abrupt perspectives, a variety of subjects and pictorial techniques… Neo Rauch was born barely a year before the raising of the Berlin Wall split his country in two and confined him to East Germany, circumstances that shaped his early years leading up to Reunification in 1989. As an artist, his education was rooted in modern German painting, in the tradition of the Leipzig School led by Arno Rink and Bernhard Heisig.

Author: Elena Cué

Neo Rauch - Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter.

All that lies behind our thoughts ends up ruling our existence as silent forces. Those deepest, darkest places are not easy to penetrate, but if we are attentive to the signs we produce, we can decipher and understand a bit better what we are made of. The dreamlike imagery in the works of Neo Rauch (Leipzig, Germany, 1960) is laden with symbolism: the overlapping of apparently unconnected scenes, abrupt perspectives, a variety of subjects and pictorial techniques…

Neo Rauch was born barely a year before the raising of the Berlin Wall split his country in two and confined him to East Germany, circumstances that shaped his early years leading up to Reunification in 1989. As an artist, his education was rooted in modern German painting, in the tradition of the Leipzig School led by Arno Rink and Bernhard Heisig. Rausch creates his figurative works from a blend of influences and in an abstract-surrealist vein with traces of Socialist Realism. His works are in some of the most important museums around the world.

As I was admiring his recent works on a visit to the David Zwirner gallery in London, I noticed that the painter was present and resolved to ask him for an interview, which he accepted with a penetrating glance and few words.

Which artists from the Leipzig School were your models, and how did Socialist Realism influence your painting?

When I finished my studies, the idols of the Leipzig Academy were Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Karl Hofer, Salvador Dalí and Otto Dix. This means that, as far as the parameters of figurative painting were concerned, the training we received was distanced from ideological precepts. In other words, in the 1980s, Socialist Realism had long stopped being a unifying concept. The generation of our professors had already succeeded in shedding that paradigm. Strong individualism took its place, whereas a critique of the social circumstances of the time was more or less veiled.

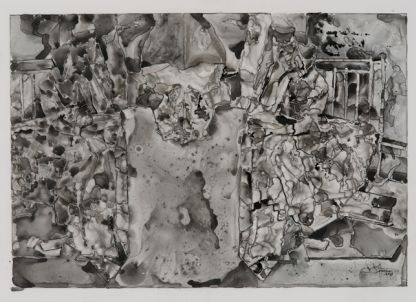

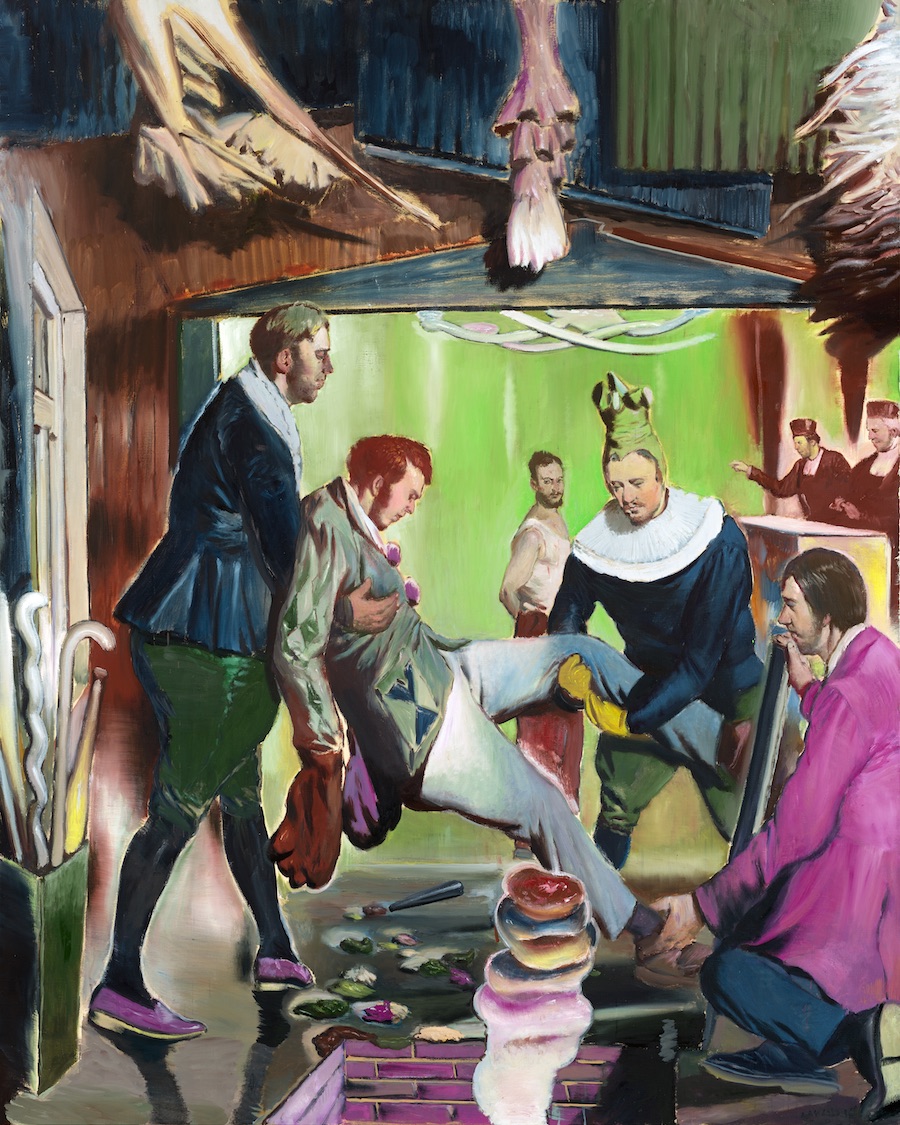

ZUSTROM. Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin. VG Bildkunst

How was your work affected by the socio-political events that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the opening to the capitalist world? What were the most important changes in your life?

By that time, I had been able to seal off my artistic production from current political events, which could only filter in to my works –if at all– in homeopathic doses. When Werner Tübke was asked how he had experienced the arrival of the Red Army in 1945, he answered: “I was sitting in my garden painting wallflowers.” I was so busy at that time finding myself in my work that the major upheaval caused by political and social situation could only have been processed in my work as a very mild aftershock. The greatest change in my life came with the birth of my son in 1990. That’s when I crossed over into greater responsibility, but at the same time it offered me the chance to embrace child-play once again.

And all children dream of comics. One of the more disconcerting elements, as such, in the mixture of styles in your work is its references to comics. Why do you introduce these Pop symbols?

Comics provide figurative painters with a reservoir of raw materials of a very special kind. These reserved materials can be integrated as vivifying elements in the various successions of the “evolution of the classical image”. It is material that has not been worn out, that is innocent and above all that speaks to the child inside the painter, and keeps that child alive.

And the unconscious is another endless stream of raw material that has a strong presence in your compositions. Space and time lose their properties, making way for a dreamlike, otherworldly perception...

The unconscious is a never-ending source of imageries that seem to just be waiting to reveal themselves in my paintings. It’s an area where things are still all jumbled together and don´t have specific intentions, material that the painter is allowed to configure at will.

VERSENKUNG. Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

Is painting then a way to bring order to your thinking? Do you feel a strong need to communicate?

When I paint, I don´t think, and instead I surrender myself completely to my feelings and to what the canvas demands of me. To me, this means bringing order, not to a mental space, but to the space of the unconscious. As a painter, I try to systematize the irrational, and to do that in painting after painting. This process is not easily reconciled with communication as it is most commonly understood.

And that leads to the disorder in your scenes and an obvious fondness for chaos. Do you understand the world you live in?

In my darkest moments, I feel like I might understand it. This means that its acting mechanisms come to light in an uncensored, open fashion. Thank God there are also moments of clarity, when lighter and apparently unrelated things swirl around me and awaken in me a fundamentally poetic spirit.

The absurd, the nonsensical, the mixture of sensations such as fear, the search for safety, melancholy, solitude... Like Calderon de la Barca said, “life is a dream, and dreams themselves are only dreams.”

I dream, therefore I am; or in the words of Hölderlin: “When we think we are beggars; when we dream, we are kings”.

DER STÖRFALL. Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

Some old masters are clearly present in your paintings. Can you tell me which ones have influenced you the most?

The most important influences are the ones I came into contact with after 1989, and on my first trips to Italy, where I experienced Giotto’s frescoes in Assisi as a kind of call to order, and Giotto seemed to guide me away from the confusion of semi-abstract doodles. Before him, there was Francis Bacon, an essential guide towards pictorial freedom and an enterprising spirit in terms of creativity beyond all academic restraint. Lastly, I should also mention Piero della Francesca, Tintoretto, Velazquez and Balthus.

I find many Old and New Testament symbolisms in your painting. How important is religion to you?

That is the main question. How do I see religion? Well, the symbols in my paintings are more likely extracted from the collective subconscious, or if you prefer, the Akasha –that ethereal undercurrent that links us all and carries everlasting images. Of course, both contain the pictorial materials of the sources you mentioned, even though I may not address them in a conscious manner. I would define myself as an atheist with occasional bursts of pantheism. As a painter, what matters to me is irrationality as a reservoir of inspiration. As someone living in the present times, however, and as a witness to the irrational events of religious origins that have taken place, I am determined to seek out my salvation in the ideals of the Enlightenment.

TIEF IM HOLZ.Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

- Interview with Neo Rauch - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Ed Ruscha (1937, Omaha, Nebraska) is one of the survivors of the American Pop Art, movement that has maintained it's influence since it emerged in the mid s XX until now. His work articulates images and words, providing them with a multiplicity of meanings, prompting thinking. Through Ruscha we can travel by car along California landscapes: roads, buildings, and billboards, where images and texts are intertwined. His work has been exhibited in the best museums in the world, such as, among others, in the Whitney Museum in New York, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris or in Spain in the Reina Sofia Museum. Despite his nearly 80 years of age he retains all his charm and appeal, physically and intellectually. On the occasion of his last exhibition in the Gagosian Gallery of London, we talk about his work and career.

Author: Elena Cué

Ed Ruscha. Photo: Elena Cué

Ed Ruscha (1937, Omaha, Nebraska) is one of the survivors of the American Pop Art, movement that has maintained it's influence since it emerged in the mid s XX until now. His work articulates images and words, providing them with a multiplicity of meanings, prompting thinking. Through Ruscha we can travel by car along California landscapes: roads, buildings, and billboards, where images and texts are intertwined. His work has been exhibited in the best museums in the world, such as, among others, in the Whitney Museum in New York, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris or in Spain in the Reina Sofia Museum.

Despite his nearly 80 years of age he retains all his charm and appeal, physically and intellectually. On the occasion of his last exhibition in the Gagosian Gallery of London, we talk about his work and career.

Your latest works are shown in this exhibition "Extremes and In-betweens". On the canvas, against a painted backdrop, a series of oversized words gradually fade out and their meaning goes from the universal to the specific, almost disappearing.

You know, I think that this work comes from a book that I made in 1968 called Dutch Details. I was invited to the Netherlands to make a project. I wanted to make some pictures in this little northern town of Groningen in the Netherlands, so I took photographs and it was like a progression. I took pictures across a bridge one very wide picture and then I walked forward, took another picture, all the way across the canal to the window of someone’s home and inside the window were flowers in a vase. And somehow, that’s always stayed with me, so I think that these works come out of that spirit. I think that anything I do as an artist comes from something that I did years ago and so I’m just a variation on a theme.

Ed Ruscha, Galaxy, 2016. Photograph: Ed Ruscha/Courtesy Gagosian

Then usually, your inspiration comes from your memory?

Yes, but also things that I see in the street and in life, I’m influenced by all these things. But it usually is somehow affected by things that I did many years ago. So when I was 18 years old, I maybe had the basis of what I do as an artist. And everything I do is just a little bit off of that.

Could you describe your pictorial evolutionary process, from a more emotional art like abstract expressionism to the more rational conceptual genre?

Yes, in some ways I feel like abstract art is everywhere and it’s quite an achievement. It’s a very modern step forward, the invention of abstraction. You know, 150 years ago people starting making abstract art. And it was a really important step to do art that is not figurative. And so abstract art affects everything that I do, and that most people do. You know, every artist wants to open the gates to heaven and I’m really no different. I’m influenced by almost everything I see: bad, good, in-between.

You have described yourself as an image-maker; could you tell me about that?

I love abstract expressionism. For me, unlike the artists who cultivate it, I’m better when I think of something in advance and then plan the painting out. I have a preconceived idea about what I want to do. So that’s my approach, and in many ways I don’t think like an abstract expressionist. I think like a person who plans the work out.

So it is more conceptual than emotional?

Yes, but emotion can enter too.

But mostly control…

Yes!

Ed Ruscha, Hollywood, 1968. © 2012 Edward J. Ruscha IV. All rights reserved. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Your landscapes of broad horizons, raking light, twilight mystery, dramatic sunsets, desolate places… I find enormous romanticism in the immensity of your landscapes, a sort of modern Caspar David Friedrich. Is there romanticism in your work?

I don’t put romanticism in my works, but I hope that it’s already there. I love Caspar David Friedrich’s work. But you know, he was a very individual and impressive artist. It’s hard to describe him, but I see so much in his work. And not just the figure that’s standing looking out over the horizon but he did drawings and paintings of ice that was fractured; they look like geology. You know, his work is great.

Yes, it beckons one to look beyond, towards a metaphysical dimension. Are you interested in what lies beyond the physical?

I certainly don’t think of my work as being mystical or cosmic. It’s more simply my contact with the world as it is, so I don’t delve into mysticism. I know a lot of artists do; they believe in that. But I’m maybe not there. I’m more practical I guess, or visually sometimes I don’t know where I am with it, and I’ve been doing this for so long that I forget why I’m doing it!

Your work is full of meaning...

Somehow my work took on the elements of words and English language, and somehow I got onto that because I studied printing and I wanted to be a sign painter. From there it went to printing, to books - I love books and I’ve made books for many years. So those elements are there, I can’t escape this. And I don’t want to escape it either, it means a lot to me.

In some of your paintings these words or texts have contradictory meanings with the image. They convey irony, humor. What is your intention?

Well I don’t set out to make something that’s funny. Irony is another subject – I mean it’s just the basis for my thinking. It comes from all different directions. When I did these paintings here, I had to establish some kind of platform for my thinking and a lot of it had to do with color. I wanted to establish a color and I arrived at this raw umber. I like raw umber – it’s almost like a color that forgot it was a color. And so I thought, that’s the answer right there. To make a stage setting for these thoughts that are the progressions of thinking – you know, whether it’s time or whatever it is - it all just has to come together somehow.

Ed Ruscha, Manana, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

What disturbs your mind? What drives you to paint?

I think that everyday life is enough to produce the incentive to paint. It’s not necessarily the torture of unknown things that make me want to explain that. It’s like living in an isolated world and somehow working within that world with the limited tools that I have and so I just keep working. To explain it is difficult.

You do not appear to be one of those tormented artists…

Well a tormented artist might be somebody who is an artist one moment and then is not an artist and it’s a struggle. For me, the immediate struggle never really happened but there are all kinds of elements that enter into the making of art and it’s not all joy and flowers and sweetness, you know. But at the same time, it’s not all torture either, so I just see things that I want to make a picture of, and then I make pictures.

Your photographic series of buildings, gas stations and swimming pools are presented as sequential documentation. Where does this passion for the artist books come from?

Probably from childhood and traveling, and things I see that are beyond childhood. When I was introduced to the real world, I was introduced to traveling and especially in the western United States. So I was driving a lot and traveling over the west and I began to see gas stations. And so my camera was a voice for me, and I wanted to somehow record this and make - not just photographs - but I was very curious about the concept of a book. It was very magical to me. Taking the book and starting out with thinking about a book that is empty and has no images, no writing, nothing. And then you take the book with its very clean, empty pages and somehow filter your thought into these empty pages and make a story or an idea, and develop it. And so books to me are like making art.

One of your pictures downstairs is like an open book…

Yes, it drives me crazy. It comes up in a lot of my work of the last ten or fifteen years, this idea of opening up. And sometimes I don’t even know that I’m doing it, so it’s just very spontaneous and open.

And, what is the relationship between your art and movie-making?

I saw many movies as a child, and the old movies were on giant screens. There’s something really magical about that, it makes a big impression on my life. In many ways, it’s like looking at a painting - except the painting doesn’t move - and here you have something on the wall that is moving and also telling a story and giving you music! So in many ways, painting is to me very influenced by movies. And then movies began to open up, the format becoming wider and wider, until you have Panavision… panavistic. So I started making paintings that were very wide and skinny like this, and it’s like opening the horizon. Making it wider, giving you more. And somehow that had a lot to do with seeing movies.

Ed Ruscha. "Standard Station", 1966

Your interest in architecture, and specifically in petrol stations is evident. What fascinates you so much about architecture?

I can imagine when I first saw the gas stations. I loved the little house, and there’s always a roof overhang that come over the top of the gas station where cars are pulling in underneath to get gasoline and drive off. And this little house at the back was so comical. So gasoline stations gave me my first exciting introduction into the world of architecture. And I even had dreams of maybe living in one of those gas stations sometimes, where you had this little room in the back. Architecture was always reduced to that for me, so I have a very fundamental belief in the simplicity of architecture.

You have experimented with all manner of materials, including organic substances such as food and drink, dynamite etc. You took part in the 35th Venice Biennale with Chocolate Room. How did this experimentation begin?

I saw that painting a picture was like putting maybe a skin onto a canvas, where it sits on the top of the canvas and I began to feel uneasy about that. I thought the idea maybe should be to stain something, where it goes down into the surface. I could see that organic materials and unconventional materials like axel grease or something – or if you take flowers and rub them into a canvas - all go down into the canvas, they don’t just sit on top. So making images out of something that is not paint made it very intriguing for me and interesting. I think it just offered another opportunity to do something. I was tired of painting on a surface. Now I’m back to painting a surface, you know! But in my work I have a lot of things that I can’t explain; I never liked airbrush art, but then I find myself doing airbrush art. And I never liked shaped canvases, but now I find myself doing it.

Ed Ruscha, Chocolate Room, 1970.

The external influence that the Californian landscape has, is evident in your work. However, where do you find your inspiration or the stimulus for your more conceptual work?

It goes back to nature. There are many modern things that I appreciate, but then I also love going back in my mind and seeing. I like the desert a lot, just the emptiness of it and the drama of the desert and the cacti and the vegetation and the animals and the no people idea. I mean, I love emptiness. So that also has a big effect on everything I do as an artist. It’s nature and it’s also popular culture, so I’ve got a mix of those things.

Speaking about the emptiness... why did you choose not to include people in your paintings?

When I first met Andy Warhol, I gave him one of my books of gas stations and he looked through each page and he said, oh I love it, because there are no people in it… and I’d never thought of that. I didn’t realize. Well yes, you’re right; there are no people in there. I was stunned. So I have no compulsion to describe a figure with paint. And so I don’t.

What is the most frustrating aspect of your work and which is the most rewarding?

I thought at one time that the thing I really want to have when I make a picture is the finished product. But then there’s also the getting there, the things you have to work through and the mistakes you make. Sometimes mistakes are very good. And if you turn a mistake into something that is positive, then that’s part of the end product.

How do you feel when you look back at your own work, for instance, in a retrospective exhibition. Does the distance of time render them remote from who you are today?

No, it’s actually very close. I mean, I think that things I did many years ago are very close to me today and that I’m not that far… maybe that means that I’ve not progressed very much! But when I started, I had no thought of ever making a vocation, making a living of my art. I had no concept that people would buy art and allow me to live off of it. And most of my friends were the same, you know. We did it for the glory of it, and to impress one another. The idea of making a living out of it was never there. And then the real world kicks in, and here we are!

Ed Ruscha. Photo: Elena Cué

- Interview with Ed Ruscha - - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Cristina Ojea Calahorra

A "glitch" in the Information Technology and videogame world refers to a system error that has no negative impact whatsoever on performance, playability or stability. On the contrary, it is not uncommon for users to turn a glitch to their advantage. The essence of Caroline Kryzecki's (Wickede/Ruhr, Germany 1979) work, currently on show at Madrid's Bernal Espacio Gallery in her first ever solo exhibition in Spain, is partly that kind of glitch. That unforeseen error whose ocurrence only reinforces the fact that human nature is present. The exhibition comprises a collection of works on paper of various sizes (50 x 35 cm, 100 x 70 cm or 200 x 152 cm) in which the image is achieved using only horizontal or vertical lines and is based on a motif of repetition

A "glitch" in the Information Technology and videogame world refers to a system error that has no negative impact whatsoever on performance, playability or stability. On the contrary, it is not uncommon for users to turn a glitch to their advantage.

The essence of Caroline Kryzecki's (Wickede/Ruhr, Germany 1979) work, currently on show at Madrid's Bernal Espacio Gallery in her first ever solo exhibition in Spain, is partly that kind of glitch. That unforeseen error whose ocurrence only reinforces the fact that human nature is present.

KSZ 50/35–51 Courtesy of: Sexauer Gallery, Berlin / Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid.

The exhibition comprises a collection of works on paper of various sizes (50 x 35 cm, 100 x 70 cm or 200 x 152 cm) in which the image is achieved using only horizontal or vertical lines and is based on a motif of repetition. These works are closely linked to the digital world by their automated appearance. A carefully carried out job in which each impeccably-drawn line is separated from the next by a mere 3mm and would seem, at first glance, to be the printed product of some digital data processing mechanism.

However, spotting that tiny defect in the system, that almost imperceptible line that is out of place, helps us to step away from a "digital" reality. Like when some discordant note in a dream makes us aware that we have just dreamed, those little mistakes in the drawing are what make us realise that what we are looking at is, in fact, totally analogous and hand-drawn with pens.

KSZ 200/152-06 Courtesy of: Sexauer Gallery, Berlin / Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid.

Kryzecki's methodology manages to stop time in its tracks, not just for the patently laborious determination to find her own language, but also because she is radically opposed to what modern society demands of us. In a world of fast and fleeting consumerism, chained to constant new starts and the incertitude of our "liquid modernity", as described by Zygmunt Bauman, the artist here reclaims our attention to detail and a reflection on a geometric abstraction that seems encripted and apparently inaccessible to the spectator.

She alone has access to an algorithmic system made up of patterns of repetition, a system of codes all her own that, nevertheless, possess a huge power of attraction as much for their aesthetic beauty as for their ability to depict infinite horizons and to hint at realities beyond mere lines on a page. The works require close inspection and dedication although, in some ways, there is no secret message to decipher. The work is the representation of Kryzecky's interpretation of the parameters of her environment for which she needs to establish structures and to order the chaos of what is considered "normal". It's an intimate and delicate work that transports us into its universe.

KSZ 100/70-11 Courtesy of: Sexauer Gallery, Berlin / Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid.

Caroline Kryzecky's work has as a starting point an archive of the pictures she has compiled, focussing on landscapes and, especially, the decorative images we see around us in our day-to-day lives. These references have always been present in her work, linked to geometry in both her more abstract paintings and in others less so where the lines were always accompanied by figuration. Without following pre-established parameters, her trajectory sometimes involved experimentation with objects or sculpture-like pieces. But her art took a different and deliberate turn when she started a residency in Istambul in 2010, arriving with absolutely none of her previous working materials or media at all. This was a voluntary gesture of closure that enabled her to discover a language with which to best express herself.

Blue, black, red and green are the colours she uses in her works - those being the four basic ballpoint colours - and she limits herself to the paper dimensions mentioned above. This self-imposed restriction has favoured the creation of her own personal code and has opened the way to the possibility of an infinite variety of combinations. And as she herself admits, this has served to expand her creative potential. In the same way that "error" became a powerful element in her work, she has been able to turn limitations into her greatest freedom.

View of the exhibition. Courtesy of: Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid

Demonstrating emphatically a divergence from other artforms based on shortcuts, she engages directly with each piece, tending and refining it until a language is obtained that needs no illustrations, whilst producing the most abstract and poetic version of the work. On entering the exhibition, visitors find themselves surrounded by the beauty of slow movement and transported to a lucid dream of infinite worlds.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

Caroline Kryzecki: Between The Lines

Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid

26 October ~ 30 November 2016

- Details

British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2016) once said "Rather than a style as such, what I do is try to stay always at the forefront of innovation”. It’s a clear expression of how she became a key figure for many in the evolution of an experimental architecture that imagined the new spaces of the 21st century. Hadid conceived of her work as a transformation of the vision of the future, using innovative concepts and forms to create cutting-edge works and designs full of originality, power and vanguardism. Hadid’s architectural language possesses an indisputable personality and unique character that is usually instantly recognisable. Her expressivity resonates with her outstanding personal achievement; an immigrant of Arabic origins, she was a unique voice in a profession that was never considered appropriate for women.

British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2016) once said "Rather than a style as such, what I do is try to stay always at the forefront of innovation”. It’s a clear expression of how she became a key figure for many in the evolution of an experimental architecture that imagined the new spaces of the 21st century. Hadid conceived of her work as a transformation of the vision of the future, using innovative concepts and forms to create cutting-edge works and designs full of originality, power and vanguardism.

Hadid’s architectural language possesses an indisputable personality and unique character that is usually instantly recognisable. Her expressivity resonates with her outstanding personal achievement; an immigrant of Arabic origins, she was a unique voice in a profession that was never considered appropriate for women. It is no coincidence that she was the first, and so far only, woman to receive the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 2004, which marked a turning point in her career.

In the 1970s she was part of the deconstructivist movement, having studied at the Architectural Association in London, and worked at the new Office for Metropolitan Architecture as part of the circle surrounding Rem Koolhaas. However, Hadid soon became independent, opening her own London-based architecture practice in 1980, with a clear will to experiment. By 1983 she had already won her first competition, with a futuristic research and design project for The Peak Leisure Club in Hong Kong. In Hadid's lesser-known early drawings we can see the blueprint of an urban cartography; a stratified, refracted, almost geological view of modern urban life which experimented with new techniques in research and investigation.

Her groundbreaking vision was confirmed in the celebrated exhibition “Deconstructivism in Architecture” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1988, which Hadid actively participated in alongside Frank Gehry, Daniel Libeskind, and many other members of that vanguard movement. From then on Hadid combined her architectural and design work with a permanent professorship at the prestigious Harvard Graduate School of Design. This combination provides a key to understanding both her formative roots in the avant-garde, and her complex artistic and intellectual personality.

The early nineties brought the first material results of Hadid’s research. The 1994 Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein revealed a concept of space characterised by the use of lightweight exteriors, sharp angles and prismatic shapes. Yet the experimentation with lighting and the integration of the building into the landscape anticipated her later work. She pursued an aesthetic vision that took in every aspect of design, from exterior structures, to interiors and furniture; as confirmed by her design for the Moon Soon Restaurant in Sapporo, Japan in 1990. With this new creation Hadid offered an interpretation of decentred space inspired by the Japanese city’s traditional ice buildings.

Vitra Campus

In contrast to the sharp angles of her early work, her later projects came to make greater use of sweeping curves, spirals, fluid lines and spaces. Structure became a form of landscape, proving that the "controlled chaos" of deconstructivism could become a material reality. During the second half of the nineties Hadid's style was evolving away from the use of flat surfaces to become much more volumetric and spatial. This can be seen, for example, in the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, which was began in 1997 and completed in 2003. This ambitious work, her first in the USA, perfectly displays her quest for new, integrative models of urban design for both interiors and exteriors. In fact, the entrance hall and the building’s surroundings were organised into an "urban carpet", which formed a continuous surface between the street outside and the interior. Beginning on the corner where the building stands, the surface curves up and inside, rising until it becomes the back wall.

Contemporaty art center Lois & Richard Rosenthal in Cincinnati

This groundbreaking concept evolved further with the National Museum of the 21st Century Arts in Rome (MAXXI). Inspired by the serpentine waters of the River Tiber, the building develops the idea of an open urban campus over which the interior spaces extend to include or integrate the entire city. Its elaborate forms, sinuous contours and varied, overlapping dimensions create a spatially complex, yet always functional structure. Both the interior and exterior surfaces of its curved walls are used to exhibit projections and installations, capturing the attention of visitors.

National Museum of the 21st Century Arts in Rome (MAXXI)

From the beginning of the new millennium Hadid's powerful projects confirmed time and again her goal to break with architectural convention in whatever she did; turning buildings into landscapes and rethinking their physical and formal limits. For example, the Guangzhou Opera House in China is probably one of her most spectacular works in terms of its monumental dimensions. However, despite the sheer size, the fluid movement and dialogue between its four large independent structures do not clash with the other urban spaces of that rich Chinese city, where it functions as a cultural nerve centre.

Guangzhou Opera House

Of course, the relationship between the building and the city is a constant theme in her work. The Bridge Pavilion, constructed for the Expo 2008 in Zaragoza, is a paradigm example and one of the most representative works of her career. This extremely complex work of engineering combines technical virtuosity with functionality; the contents and interiors were designed to be a space of collective reflection on the theme of sustainable development, hosting the exhibition “Water – A Unique Resource”. The fact that this dialogue on water is realised over a river as symbolic as the Ebro not only accentuates the scale of the global challenge, but acts as a window into the heart of the city, which it invites us to contemplate "from within".

In a world structured by shapes, Hadid's groundbreaking projects broke with the habitual, the lineal. Her style demonstrated a perfect command of non-rectilineal forms, particularly three-dimensional shapes. The elegant, undulating exterior surface of the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku has a geometric fluidity, folding in on itself to form both the concert hall and the interior hall. Moreover, her style came to dispose of traditional decorations, as seen in the London Aquatics centre, one of the main venues for the 2012 Olympics. The use of concrete to make the wave-shaped roof creates a texture that also serves as a form of ornamentation.

Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku

Zaha Hadid's unexpected death at 85 has left a void in the still young history of 21st century architecture that cannot be filled. Her multi-faceted talent as architect, designer and teacher combined technical, artistic and intellectual qualities of inestimable value. All of this has forged an international reputation that extends far beyond the many accolades she justifiably received from the public and media in her lifetime. It is still too early to say whether her powerful contribution and formidable architectural personality will survive the customary criticisms and hasty judgements of the day. Only the discourse of future generations will confirm this undeniably iconic female architect's place in history. As seen in her petal-like sculpture "Kloris", Hadid's work opens up form to a myriad of new possibilities and more organic ways of representing architectural thought. That is why her life's work, which constantly challenged and reimagined the spaces and landscapes of the future, will continue after her death.

(Translated from the Spanish by Ben Riddick)

- Zaha Hadid. Biography, works and exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -