- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

This exhibition bombards us with a storm of ideas. It is a gauntlet thrown down to us by the Royal Academy and one that Gormley takes up, with all his weapons and from all sides: with lead, steel, seawater, a little blood from his veins and a battalion of iron men, dozens of soldier Gormleys. It has been four years in the making during which time, for the positioning of each and every piece, every conceivable permutation has been tried. Also during that time, the building’s architecture has been subjected to extremes, pushing it to its very limits: walls supporting massive weights, average-sized rooms housing pieces the size of something from another world, from Gulliver’s Travels, that balloon out against the doors, against the corners, while, in the adjoining room, the floor has been turned into a pond and is flooded with water.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Subject (2018), Royal Academy of Arts, London

This exhibition bombards us with a storm of ideas. It is a gauntlet thrown down to us by the Royal Academy and one that Gormley takes up, with all his weapons and from all sides: with lead, steel, seawater, a little blood from his veins and a battalion of iron men, dozens of soldier Gormleys. It has been four years in the making during which time, for the positioning of each and every piece, every conceivable permutation has been tried. Also during that time, the building’s architecture has been subjected to extremes, pushing it to its very limits: walls supporting massive weights, average-sized rooms housing pieces the size of something from another world, from Gulliver’s Travels, that balloon out against the doors, against the corners, while, in the adjoining room, the floor has been turned into a pond and is flooded with water.

However, here in this tension is where, constant and dense as a thread of light, Gormley's discourse lies. In that sense, this doesn’t seem like a conventional retrospective but a statement of the principles of the artist who, from the start, has persevered in the continuity of his incessant, unsettling question, like a gong, like a boot kicking metal and in his obsession with getting us involved, shaking us up, waking us up: "The body is more a place than an object for me: body "in" space and body "as" space. Come with me, close your eyes, look inside your body, into that darkness where the limits of space are lost, where we acquire the infinity of the cosmos." That's the key, that’s Antony Gormley's war cry.

The courtyard of the Royal Academy, with its neoclassical facade, is presided over by the statue of its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. These days, the portraitist and promoter of the “Grand Style” in painting, looks askance at a tiny object at his feet: “Iron Baby” (1999) is the sculpture of a newborn, life-sized and curled up on the ground as if it were her cradle - it is based on Gormley's daughter, six days after her birth. The artist says: "Its density suggests energy potential like a small bomb. The material is iron (concentrated earth), the same as the core of our planet.” This projectile-piece sets the tone of the exhibition.

Iron Baby (1999), Annenberg Courtyard, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Antony Gormley was born in London in 1950 into a devout Roman Catholic family: he was baptized with a name whose initials make up A.M.D.G. (Ad maiorem Dei gloriam -To the greater glory of God) which is the Latin motto of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits): "My name is Antony Mark David Gormley and I wasn’t called that by accident." From the age of six, he had to obey the strict rules of his afternoon nap: he would go up to his small bedroom where it was hot, lie down and not move, his eyes closed, while the light flooded his bed mercilessly. In that claustrophobic environment, he felt imprisoned in his incandescent cage, alone with his eyes. Gradually, he began to focus on that enclosed, oppressive space, transforming it into a different place: dark, cool, floating in a deep, blue infinity. Sixty years later, he is a sculptor whose work wrestles with the concept of what it means to inhabit the human body.

Gormley boarded at a Benedictine public school and travelled to Lourdes as a volunteer, all of which shattered his Catholic faith. After graduating from Cambridge, he joined the hippy trail, travelling through Turkey, Syria and Afghanistan to India: "the place where things started to make some sense." He spent two years studying Buddhism: "Passion for meditation took me to a place I’d already been to as a child."

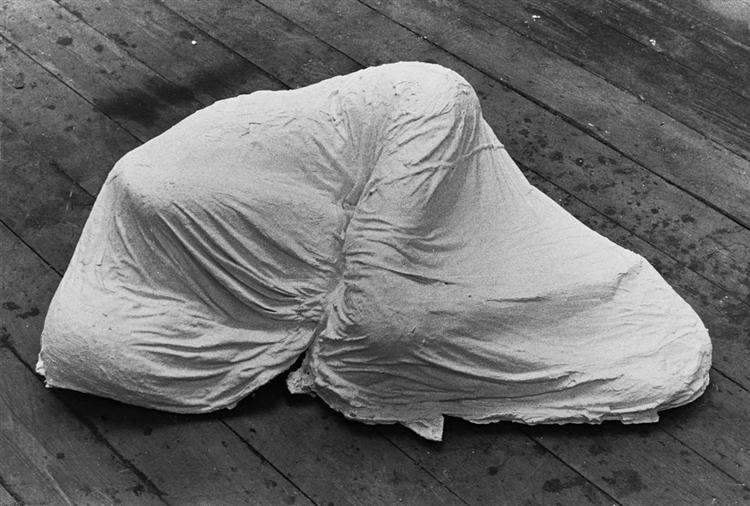

His experience in India planted the seeds for his early sculptures. Sleeping place (1974) is the silhouette of a man lying down in the foetal position, covered by a white cloth. "For two weeks I wandered around Calcutta. The streets were made up of noise, the suitcases, the car crashes, the food stalls on the ground, the rickshaws ... and in the midst of all that were these bodies just lying there, not moving, covered up and noone knew if they were dead or alive. Sleeping Place was my way of turning that experience into an object."

Sleeping place (1974)

Since 1981, Gormley has been working with the body and choosing his as the nucleus for everything. For the next 15 years, Vicken Parsons, his wife, accomplice and only assistant, wrapped the artist's naked body in plaster mesh in different poses, leaving only a hole for his mouth, trimming it and then freeing him from the plaster casing. And so began Gormley’s artistic hallmark, an army of iron men who today populate the world from the English coast to the rooftops of Manhattan. These "bodycase" sculptures - of which Lost Horizon I (2008) is the piece featured in this exhibition, consisting of 24 figures all pointing in different directions from the walls, floor and ceiling, questioning the perception of what is above and what is below - evolved thanks to cutting-edge infrared technology and a custom-made computer program which allowed him to take his dimensions and postures even further, delving deeper into abstraction. Increasingly, schematic "men" began to emerge whose bones, muscles and skin were decoded into computer or industrial forms, physical pixels made of rusty iron, bricks of metal that, like Lego, constitute beings without a name, without an identity. These are the Slabworks (2019) in Room 1.

Lost Horizon I (2008), Royal Academy of Arts, London

Slabworks (2019), Royal Academy of Arts, London

Antony Gormley has just turned 70 and the Royal Academy is thus honouring his trajectory here. However, Gormley’s works, as open-air sculptures, grow with an amplifying force that pierces urban and rural landscapes like acupuncture needles: beaches, deserts, Italian palaces and industrial England’s chimneys ... The sculptor leaves his solitary men there, like a forest of questions, forcing us to understand that place in a very different way. In the words of Simon Schama: "They are actors, not statues."

Another Place (1997), Crosby Beach, Merseyside, Great Britain

Gormley also wanted to give voice to those who did not have one - "One&Other" (2009) with 2,400 volunteers occupying the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square - and "Sculpture for Derry Walls" (1987) was his link to 'The Troubles' in Northern Ireland. Two back-to-back figures in symbolically Christian cruciform form, cast in iron to withstand the impact of bullets, were placed at strategic border points between Catholics and Protestants: "As soon as the sculptures came down from the cranes, a crowd of young people huddled around them, spitting at them. A young man on my team flew at them with a hammer at lightening speed. I will always remember that moment. Those gangs burned our sculptures, hung tires from their necks and set them on fire. The next morning the remains of the scorched tyres looked like crowns of thorns."

Sculpture for Derry Walls (1987), Derry, Ireland

A connection with the spectator has also led him to invite the public to collaborate on the creation of his work. "Field" (1990) is an ocean of small clay figures made in three weeks by a family of brick builders outside Mexico City: "Every time I've done "Field", I've used local people and materials. That time I gave them some very basic instructions: Take a piece of mud, shape it with your hands, make two incisions for the eyes and see what becomes of it, let it make its own shape, which will be unique. What turns out, or better said, what is freed when you give a group of people a common goal? The result is magical."

The first time he did "Field", there were over 1,000 figures. When he did "Field for the British Isles" (1993), the army of small mud men surpassed 40,000. "I tried to physically offer a voice to those who did't have one. I grew up in the 1960s, in an orderly world where ordinary people were gradually reaching positions of power. That's the spirit of "Field", filling up every last inch of a museum so the pleasant experience of being in a museum is transformed into a confrontation with the accusatory looks of thousands of eyes challenging us," Gormley explains.

Field for the British Isles (1993), St Helens, Liverpool, Great Britain

In 1994, Gormley won the Turner Prize which brought him recognition and an infinite launch pad for taking on larger projects. "Angel of the North" (1998) is a 20m high totem pole of 200 tonnes of angel-shaped steel. Its deployed wings stretch as wide as a Jumbo jet’s. Its location, just off the busy A1 motorway near Gateshead, makes it one of the most viewed works of art in the world.

Angel of the North (1998), Gateshead, Great Britain

The spirit of these works can be felt to vibrate throughout the 13 rooms of the exhibition which also display Gormley's drawings and which, like a 21st century Leonardo da Vinci but tinged with blood, oil, earth and flaxseed oil, demonstrate a sculptor's obsession with drawing. They are like diamonds shooting out hard, fast and direct like arrows from the neurons of his ingenuity.

Mould (1981), Private collection

This exhibition is a co-production between spectator and creator. The sculptures demand our physical and imaginative participation: we are obliged to bend down, crawl and lose ourselves among them. Also fascinating is the play on scale with works the size of the palm of one’s hand beside other colossal ones. "Clearing VII" (2019), composed of miles of coiled aluminum tubes tracing an arch between the floor and ceiling and wall to wall, is a "drawing in space" that envelops the visitor. "Host" (2019) fills a room with sea water and mud, evoking the depths from which life emerged. "Matrix III" (2019) is a huge dark cloud of rectangular steel grilles suspended from the ceiling. Although some of his new pieces are abstract, his reference point is always the human body. Da Vinci drew his Vitruvian Man in 1490: "Vitruvius established in eight heads the proportion of man and also that the distance from the chin to the forehead should measure the same as the hand," Gormley says as he moves towards the Matrix III mesh to demonstrate.

Matrix III (2019), Royal Academy of Arts, London

On these last days of summer light, it is still possible to view Gormley’s “Sight” installations on the island of Delos. Like modern-day sentinels, twenty-nine of his iron men defend this floating rock in the middle of the Aegean, whose name means 'The Visible' after Zeus offered it to Leto, his mortal lover, to give birth to Artemis and Apollo. Today, 5,000 years later, sees the first intervention by an artist. His sculptures greet us from strategic points: the seashore, surrounded by poppies on the ground between pillars or as strange companions to the marble gods in the museum …. while having an emotional conversation through the millennia of time. According to Martin Robertson, a British specialist in Greek archaeology, it was on this island that a marble statue depicting a woman appeared in the middle of the 7th century BC from the shrine of Delos. In the skirts of the figure reads an inscription in verse telling us that it was dedicated to Artemis by Nikandre of Naxos. That was the start of monumental sculpture in Greece.

Sight, (2019), Delos Island

But Delos is also inhabited by Gormley sculptures that are more in keeping with that other abstract canon of his - pixelated men, which are surprisingly integrated into what remains of the island's architecture today: catalogued ruins laid in rows of stone blocks by archaeologists. In this sense, it is an objective correlation of the digital age, in which information comes to us in bits that we reconstruct to create an image: "That was the original idea that coordinated the syntax of this exhibition, from these decoded bodies, like material shadows of a living body," says the sculptor.

Sight, (2019), Delos Island

Like David Hockney, Gormley belongs to that group of artists who have dedicated part of their lives to the writing of a discourse on the History of Art. In the BBC documentary 'How Art Began' and with the emotion of an English thespian, the sculptor tours the Paleolithic caves of France, Spain and Indonesia in search of humankind’s first artistic trace and the answer to a question: what triggered in homo sapiens the need to leave their footprint in time? Thus, installations such as "Sight", or "Still Standing" (2011) from the Hermitage’s permanent collection, have allowed him to confront us with his premise using the dialogue of his oeuvre with classical statuary. For Gormley, from Greece to the 19th century there was a single discourse in sculpture: the idealization of the human body. He insists that today times are different, that his work demands the participation of the viewer, that his empty bodies must be filled out by our sensations. "Cave" (2019), the jewel in the Royal Academy’s crown, is a sculpture of architectural proportions, an enormous body transformed into geometric caves with an entrance and exit. What Gormley aspires to is that we enter it and live inside its stomach, its limbs like tunnels of light and feel the cold and anguish inside the head of this Hulk, bursting into steel buckets on the ground. "I try to give the new language of modernity to the body that was rejected earlier as something classical. What I want to do concerns the abstract body, the one that corresponds to the language of Malevich, Picasso... and from there to Donald Judd and Sol Lewitt." Gormley and the past are as a propulsion of his sculpture into the future: two sensations that merge into a single victory.

Antony Gormley

Royal Academy of Arts

Burlington House Piccadilly,

London W1J 0BD

Curator: Martin Caiger-Smith

21 September - 3 December 2019

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Gormley at the Royal Academy: a discourse in iron - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Guerrilla Girls are a collective of anonymous artists who emerged during the 1980s in the United States with the aim of protesting the sexism suffered by women in the art world. Their first appearance dates back to 1985 when they demonstrated outside the Museum of Modern Art in New York to highlight the scant female representation in the gallery’s contemporary art exhibition, ‘An Internacional Survey of Painting and Sculpture’. Of the 169 artists who participated, only 13 of them were women.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Pavilion 16 of the former slaughterhouse ‘MATADERO’ in Madrid, now converted into a complex of spaces for contemporary art, ran an exhibition from January to April 2015 showcasing the work of Guerrilla Girls, a feminist art collective, and commemorating all thirty years of their activist output so far.

Guerrilla Girls are a collective of anonymous artists who emerged during the 1980s in the United States with the aim of protesting the sexism suffered by women in the art world. Their first appearance dates back to 1985 when they demonstrated outside the Museum of Modern Art in New York to highlight the scant female representation in the gallery’s contemporary art exhibition, ‘An Internacional Survey of Painting and Sculpture’. Of the 169 artists who participated, only 13 of them were women. Since then, they have not stoppedin their denouncements of the systematic lack of recognition faced by the female sex, not only in the artistic but also in business and political spheres. They reclaim the conspicuousness by their absence of women in the art world and condemn the lack of support from public institutions for their work as well as the widespread invisibility in the cultural and social spheres. They seek not only equal rights but equal opportunities in a world where men set the rules of the game. They want an "I" beyond the dichotomy of sex and gender. Biological sex has become a social genre that discriminates against and relegates women.

Possibly what stands out most about the Guerrilla Girls’ retrospective is how it raises awareness that feminism, as a protest movement for liberation, has ceased to be present in today's public discourse, as compared to the interest it sparked in the 1980’s when it became visible not only on the streets but also in academia with the emergence of the first Women's Studies courses at universities in Britain, France, Italy and the United States. Its presentation now in Madrid’s artistic circles, and previously in Bilbao, constitutes a great opportunity to reflect on those certainties that have accompanied those great stories in art history (invariably written by men) and the possibility of returning to them with a greater capacity for analysis and having a better interpretation of "woman” as a social subject at our disposal.

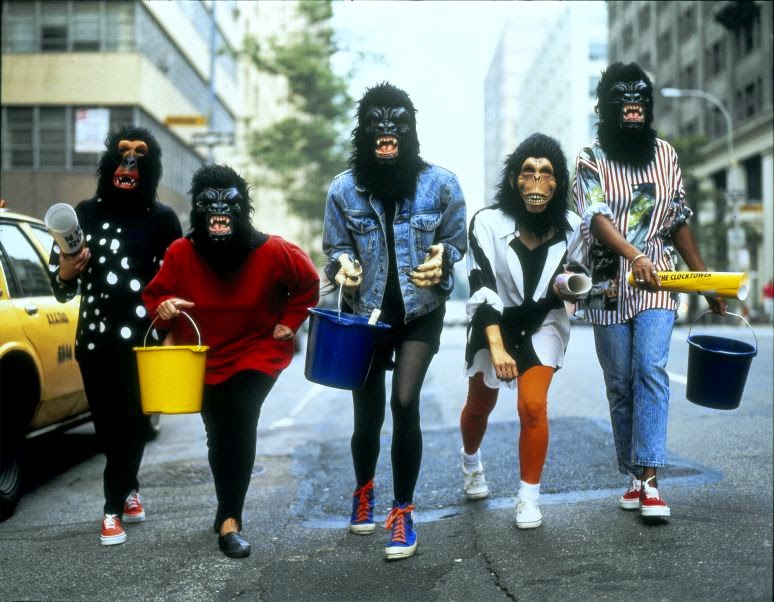

The gorilla masks they wear in public are the identity marker of a group who seek anonymity for their members and use, instead of their real names, those of illustrious women who have disappeared into oblivion. All we know is that their aliases are those of female artists or those linked to the art world. Their image serves as a vehicle for their own particular discourse, becoming the subject and object of their protests. Sexual discrimination, the shortsightedness of the artistic world, the paradox of believing that art is at the forefront of the societal avant-garde, the use of statistics as scientific findings and wake-up calls alerting us to other marginalized groups are just some of their battle cries.

The Guerrilla Girls’ most representative work is their posters, of multiple sizes, and varied designs, full of ironic messages that bring a smile to the visitor’s face and often also a reflection on the power of the written word in the age of the image and an opportunity to free it from its normative chains. Interestingly, as I have already pointed out, statistics are one of the weapons this group uses to emphasize its exposes on a recurring basis. An example of this is a 1985 poster with the following caption, “These galleries show no more than 10% women artists or none at all.” And another from 1989, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum? Less than 4% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but, 76% of the nudes are female.” The poster is an easy way of attracting the visitors’ attention and, in order to do this, the activists seek to mazimize their voices by positioning their messages in the most conspicuous places in museums and art galleries. Participation in forums, publishing books, magazines and documentaries, giving interviews and seeking out followers for the cause are other forms of activism. The collective no longer has room for any more members but it does encourage us to support their demands from wherever we may be.

Xabier Arakistain, curator of the exhibition and a great connoisseur of women's issues, has brought together practically all of the group's work since their formation and invites the viewer, in date order, to understand these women’s processes of creation and their forms of protest. Their message has been disseminated across the world and it is possible that their ironic and humoristic oeuvre of complaint, accusation and social criticism will serve to sensitize the public and change their perception of women in the arts.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Guerrilla Girls - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Geumhyung Jeong is an interdisciplinary Korean artist with roots in the worlds of theatre, animation and dance. Her arrival onto the contemporary art circuit as we understand it is relatively recent and, in just five years, she has exhibited her work and presented her performances in such places as the TATE Modern and the Delfina Foundation in London, the Kunsthalle in Basel and the Hermès Foundation in Seoul. The themes that Jeong explores in her work resonate perfectly with the hot topics of contemporary art today but she does so from an outsider position that lends her an air of the ‘genuine ingénue’.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery

Geumhyung Jeong is an interdisciplinary Korean artist with roots in the worlds of theatre, animation and dance. Her arrival onto the contemporary art circuit as we understand it is relatively recent and, in just five years, she has exhibited her work and presented her performances in such places as the TATE Modern and the Delfina Foundation in London, the Kunsthalle in Basel and the Hermès Foundation in Seoul. The themes that Jeong explores in her work resonate perfectly with the hot topics of contemporary art today but she does so from an outsider position that lends her an air of the ‘genuine ingénue’.

As an artist focused primarily on performance, her exhibition ‘Spa & Beauty’, happening simultaneously in London and Madrid, is a reflection on this very concept. Whilst the London exhibition presents the idea of performance without her, in Madrid she performs the ‘demonstration’ and installation herself.

Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery

‘Spa & Beauty’ is a project commissioned by the Tate Modern in which the artist creates a slightly modified spa, perhaps one with that sense of “the uncanny” that Freud talks about. The installation consists of furniture and objects typical of a spa (a bathtub, a massage table, brushes, sponges, …), but Jeong gives it all a twist by including mannequin limbs and teleshopping videos downloaded from the internet that add other levels of meaning and aim to portray a society obsessed with physical appearance and wellbeing. The irony with which she represents the health and beauty industries does not go unnoticed. Defining herself as a collector, the artist presents us with all the objects in her collection, objects that usually come into direct contact with the skin or that allude explicitly to the body. Further to her criticism of the beauty industry, there is also a discourse around the human and the mechanical in her work. Two of the videos that form part of the exhibit reveal the process involved in the production of a brush, one of them handcrafted, the other made by machine.

Jeong defines her ‘Spa & Beauty’ performance as a 'demonstration', a little-used term in the art world, but very revealing in that it describes a performance that seeks to give us a close-up of work in a spa. It has, therefore, something of the theatrical about it in the way it makes us participate in a fiction and accept the 'illusion' of actually being in a spa. In that sense, it might be appropriate here to mention Baudrillard's notion of simulation to describe how the project alludes to a reality familiar to all of us but is in fact one born of simulation.

Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery

Geumhyung Jeong is an incredibly versatile artist, each of her projects broaching new themes as she implements different strategies of staging and interpretation. For instance, in her performance piece ‘7 Ways’ at the Tate in 2017, she dazzled with her skill at moving around the 'stage'. She interacted with objects from her collection but, on that occasion, not only did she create the illusion that she was moving the objects but also that they were the ones moving her. In her 2019 ‘RC Toy’ performance at the Kunsthalle in Basel, she created robots to which she attached body parts. The result was creatures, half-man-half-machine, with which she interacted in an overtly sexual way. The remote control activating each robot was located in the erogenous zones of the other robots so that they were all interconnected and activated by her presence in a kind of robotic orgy.

This is a groundbreaking debut from The Ryder Gallery which has just opened its doors in Madrid as part of an ambitious project involving over five years’ work at its headquarters in London.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Spa & Beauty. Geumhyung Jeong. The Ryder Gallery - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Does science distance us from God? Professor of Economic Structure and member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences Ramón Tamames (Madrid, 1933) delves into the cosmology between scientists and philosophers in the already longstanding quest for the Primary Cause or Higher Intelligence as origin of the universe. The title of his latest book 'Searching For God In The Universe. A worldview on the meaning of life' (Erasmus) gives a clue as to its contents.

Author: Elena Cué

Ramón Tamames. Photo: Elena Cué

Does science distance us from God? Professor of Economic Structure and member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences Ramón Tamames (Madrid, 1933) delves into the cosmology between scientists and philosophers in the already longstanding quest for the Primary Cause or Higher Intelligence as origin of the universe. The title of his latest book 'Searching For God In The Universe. A worldview on the meaning of life' (Erasmus) gives a clue as to its contents.

Are you searching because you don't have faith or because you do and you want to back it up with science?

Essentially, it's just a case of my keen interest in cosmology and how little I may or may not understand of advanced physics. I'm also interested in the origin of everything and the meaning of life. And it's not actually that I don't have faith. In fact, I don't really get involved with revelation or mysticism, the usual channels that lead to faith. I respect it, though. Actually, I had a Christian upbringing and I've never stopped experiencing "moments" in that regard. I'm not a practitioning Christian but there's always "that certain something".

Have you arrived at any conclusions?

Yes, in that physics doesn't have all the answers or that it does but in a somewhat fantastical way. For example, Hawking told us that the universe was born by chance from a quantum fluctuation that produced the Big Bang. Naturally, that explanation leaves us cold, because ... what's behind all that? Where's the sense to it? That's what I've always wanted to research because, at the end of the day, the notion I have happens to very closely match that of one of my heroes, Isaac Asimov, who says that we're a staged planet: we're here and we're being observed by someone seeing how we manage, what evolution we follow and how we behave.

Would you say that was the crux of your search?

Alongside the meaning of life, there's someone at work behind it all, a superior intelligence that ushered in the Big Bang, gave rise to the computer and set material and biological evolution in motion.

What would this God have to do with the Christian God?

The act of creation. Essentially, the 'fiat lux' of the Vulgate, or the Latin version of the Bible, means "Let there be light". Many scientists say they don't like the Big Bang Theory because they think it's got a theological context. They say it's like God from the Book of Genesis. But that's just them arguing for argument's sake because the universe has to have had an origin and the most logical one would seem to be that one. I think the Christian God is a Judeo-Christian revelation belief. I respect that and I don't judge it. That's the Christian God and the Son of God. But it's a revelation. I come from a scientific viewpoint and I understand that God, as a superior intelligent being, might have many human manifestations, one of them being that of Christianity but, personally speaking, I think that's the most exalted of all the manifestations – because we're very influenced by that whole culture.

Have you encountered God yet in this quest?

No, I haven't. In any case, what I don't claim is that a God will reveal itself via a voiceover going "Here I am". Everything to do with creation is so absolutely left-field that I've ended up agreeing with the Seven Wise Men, as reflected at the end of my book. Not by reason of a criterion of mere authority but because they were brilliant people who've spent a lot of time thinking all this through. But in any case, I sense there's a higher intelligence that governs everything.

To sense God through science is possible. But do you think it's also possible for there to be a scientific basis for God?

That's the exact struggle between deism – although I don't much like that term – and militant atheism, such as that esposed by Richard Dawkins, the biologist. In any case, there's no solid path of 'basis' via science because if there were, we'd all be living in unanimity. Show me that DNA contains four bases and how that's what all living things are formed from. And tell me that's God's alphabet. But it's a parable, not a reality. If there were any proof, there wouldn't be any controversy.

You say that, in the 1980s, many scientists adhered to the belief that evolution didn't happen by chance or necessity, but by way of a teleological principle, namely, that it has a finality.

That's something that's been argued since at least pre-Socratic times, for over 2,500 years. Suffice it to say the discussion is a permanent one. Aristotle was already saying of Leucippus and Democritus that they had to have been drunk as skunks because they were going around saying it made no sense, when everyone knew, including Aristotle, that it did make sense and that there was bound to be a teleology.

And what do you think?

I think it's an ongoing discussion that, in a way, opens up into the philosophy of the meaning of life. Kant himself, around 1790, wondered what the point of it all was, giving rise to these four famous questions: What can I know?; What should I do?; What can I expect?; What is Man? And that way of thinking is typical of the Enlightenment. And what is the Enlightenment? Well, according to Kant, it's reaching the age of maturity.

That's where we're at. If I could offer any definitive examples, I'd give them and be over the moon! Actually, I sent my book to the Pope and his Secretary of State replied to me with an autographed photo of him. Saying nothing at all.

Do you think there's less respect for institutuions, governments, beliefs, etc nowadays?

I think that's always happened. In the Century of Reason, Baron d'Holbach stopped believing in God and laughed at Christians. The thing is, sometimes it's been more tolerated and permissable than others. Nobody can doubt that in 16th and 17th Century Spain, anyone agitating too much in that regard got what was coming to them. In that sense, there's always been unrest. What's happening now is that people demonstrate more via social media, they're bolder, knowing full well that public freedoms and guarantees allow them to do so. The media are very much to blame for hypertrophy. They induce changes in the general mindset, no doubt about it, and things that were unacceptable in formal societies a hundred years ago are acceptable now.

How do you see the Spanish economy right now?

I'll say something that may seem like an exaggeration but it isn't. The economy is doing quite well and comparatively better than the rest of the European economy, despite the politics, because political instability is having quite an effect on it right now and despite the Administration, which I would call a great lumping monstrosity of a thing and an absolute disgrace. I'm not talking about the doctors, I'm not talking about the police, I'm talking about the Administration itself, the change in policies, in the fundamentals, and also, obviously, the bureaucracy because the problem with bureaucrats is not only that they cost us more and more money every day, but, as they have to prove they're useful, they delay and complicate everything.

So Spain is doing well ...

This country is doing well despite its Administration, which is a great lumbering monstrosity of a thing. There's the answer. And why is it doing well? Because we have the best entrepreneurs in our entire history. And our stock market, Ibex 35, is symbolic of this entrepreneurship we have. There'll be some doing better than others but that a group of companies does almost 70% of their business outside Spain means that they are competitive. That's what you have to recognize.

Which economic proposals do you think would be needed for improvement?

There’s no lack of proposals. And fortunately we have proposals that are very positive indeed, that come to us from outside the country. My opinion is that "Super Mario", aka Mario Draghi, has an impressive policy for European economic recovery and he hasn't allowed the Euro to go under. And I think there are many other recipes for success but they're being obstructed by the 18 ministers we have, the corresponding secretaries of state, the thousands of director generals, and so on.

You write that skepticism is growing about whether CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming. And you speak at length, warning of the danger we face in the short term in your book 'Facing the Climate Apocalypse' (Profit Editorial).

That's where most of the uncertainty lies, actually: the fact we don't know if we'll be in time or not. Someone well-versed in this, James Lovelock – who worked at NASA and is the author of the Gaia thesis – argues that Earth is a self-regulating organism and that at any moment Gaia's revenge might come, namely, to expel man and let evolution continue on, but without the human species. Perhaps that's a scientific exaggeration to make people wake up, just as the young Swedish girl Greta Thunberg has done, saying that climate change is humanity's worst and foremost problem.

The problem is whether we get there in time or not ...

I have my doubts, serious doubts. Not exceeding 2°C above the temperature benchmark set before the beginning of the Industrial Revolution as the main objective of the whole 2015 Paris Agreement is a pipe dream. What's clear is that we're continuing to accumulate greenhouse gases and that the symptoms are fatal not only in the Arctic and the Antarctic, but also in glaciers and droughts, etc. The problem is to get them under control before it's too late and Lovelock says we won't.

Why is it a pipe dream?

Because China will continue to emit greenhouse gases without curbing them until 2038. And the U.S. has also, theoretically though not legally, withdrawn from the Agreement. It's true that many of the states over there, especially on the West Coast, are doing an impressive job of reducing carbon emissions. But the point is that we haven't taken the problem seriously enough yet and the deniers are still out there. The Paris Agreement needs to be revised.

How can we decarbonize society and take care of the biosphere, without doing economic damage?

There's no problem there. The Paris Agreement, and all of its members meeting every year, more or less foresaw and saw to that. The last summit was in Katowice and, if nothing else, they agreed on accepted methods by which to measure emission reduction, which is no small thing.

I think the Climate Act, a good plan in the making, is a great start and we'll be opening some plants and closing others. And renewable energy is moving very fast. But we're still without a coherent plan. Teresa Ribera, the Minister for Ecological Transition, said to expect it by Christmas. I think the European Union is doing a good job. It has set some objectives that are attainable but the problem is whether or not they alone will suffice.

Ramón Tamames. Photo: Elena Cué

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Sidi, the latest novel by writer and Royal Spanish Academy member Arturo Pérez Reverte (Cartagena, 1951), has just been published. Sidi is the story of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, Cid the Champion, and where his legend begins: his leadership, his sense of honour, his courage, loyalty and dignity but also of pride, pillaging, blood and swords. A journey through time to that Spain of hard knock men with other ideals; men of courage and strategy in warfare, in waiting, in uncertainties ...

Autor: Elena Cué

Arturo Pérez Reverte. Photo: Elena Cué

Sidi, the latest novel by writer and Royal Spanish Academy member Arturo Pérez Reverte (Cartagena, 1951), has just been published. Sidi is the story of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, Cid the Champion, and where his legend begins: his leadership, his sense of honour, his courage, loyalty and dignity but also of pride, pillaging, blood and swords. A journey through time to that Spain of hard knock men with other ideals; men of courage and strategy in warfare, in waiting, in uncertainties ...

With the echo of the battle of Pinar de Tébar still sounding in my head, I talk to the author.

The 11th century, at the height of the Middle Ages, in a Spain of Moors and Christians. Sidi makes his living in exile. What is this novel about?

There are two fundamental narratives: the first is what our border was like in the 11th century, our Wild West. It was a very dangerous and unstable border, full of equally dangerous people. The second is a reflection on leadership: how a person is able to wield control, with the respect and command of an armed retinue of tough, dangerous men in a place that was no less dangerous. In other words, how someone is able to get others to follow him, even to die for him.

You say that there are many Cids in the history of Spain, some moreso than others.

But this one is mine. I wanted to tell the story of a Cid that hadn't been told yet, especially at the moment he took shape. I came to it with all the documentation and also with all of my own personal biography. I've poured everything I know about human beings into this kind of subject. The Cid looks at the world as I look at it: I have given him my eyes. When I speak of violence, death and blood, to a certain extent I have lived them all myself.

As a war correspondent and photographer, you've covered various conflicts such as those of Libya, the Sudan, Bosnia .... And as a writer, wars are present in many of your novels. Why this fascination with war?

It isn't fascination. I left home very young, with a rucksack and a few books, and went to a war. I learnt things in a single day that might otherwise have taken me ten years to learn. I was twenty years old and had a vision of culture that allowed me to interpret war as something more than a mere spectacle of barbarism. It was nurturing in an intellectual sense. I learnt about human beings, their behaviours, the value of things. War is horrific. I was rather more fascinated by the feeling of being close to the truth of what a human being is.

Behind the legend or the romance of the character lies the most terrible violence. In The Painter of Battles, you make a profound reflection on cruelty as an irresistible impulse. Is cruelty inherent to Man?

Human beings are a very dangerous animal, and yes, cruel. The point is that we want the world to be a certain way: that there be rules and behavioural norms as well as moral principles, an Enlightenment that made us change the way we look at the world, or a Renaissance. But the thing is that the world isn't like that. That is a tiny part of the world. As soon as you leave its confines, you add war. That's the real world. We think everything is stable but, when you have been to Beirut or Sarajevo, you realize that all it takes is a political, economic or social crisis for everything to fall apart.

What did war give you?

War gives you consciousness, a lucidity like that of a sailor who must always be mindful of the sea. And that certainty of disaster as something possible, that the Westerner has lost, our grandparents still had it. There was at that time a greater proximity to the reality of things. I've seen violence: I've seen killing, I've seen torture, and I've been friends, too, with people who did those things. And those same people who did horrible things also did, the very same day, great things. That gives you a very different measure of things. That's what I make my novels out of.

And this novel takes place at a violent time of terrible insecurity when survival was difficult. What do you think is the price we human beings have paid for the security we enjoy today?

We're more vulnerable. There's one thing in this novel that I've tried to make stand out and that's the fact that everyone spends a lot of time on the lookout because being watchful means living or dying. Nowadays, the only thing we humans stare at is our mobiles or the television. We don't see reality. The world is a hostile place often populated by sons of ******* and that is a very fair definition of what the world is. We pay a very high price for the false security we get from not looking at reality.

Now that you no longer take photos when dealing with war, what do you look at?

I look backwards. I have a rucksack full of memories that help me to live in a much more suspicious, much more lucid way, in the sense that you know what a dangerous place is, that even here we are in a dangerous place. That is why we can never relax and why we Westerners, instead, live lives of real deception.

You've been a man of action. What comparison would you make between the power of experience and the mental journey from your writing desk?

There are three ways to nurture and flesh out a novel: with what you've read, what you've lived and what you imagine. When you've lived a complex life like mine, with intense doses of extreme situations, that works for writing novels too. For example, if I am describing torturing someone in Falco, a trilogy of novels about a Francoist spy who is handsome and elegant but also a son of a ***** , when Falco tortures someone, I am drawing on my memories of Angola, on my own experience.

Swapping war for your writing desk ~ was that a radical change?

It wasn't radical. I left journalism in 1994 but I went through a period of adaptation. There were a few years that were difficult, more or less until The Painter of Battles, with which I brought that period to a close. I go sailing. And my substitute for war is the sea, the real one. On a sailboat in the Gulf of Leon in winter, I can assure you there's lots of action. I've changed, of course. There are things I can no longer do like walking 40 kilometers every day, in the blistering sun with no more shade than my hat. I'm 68 and my body wouldn't accept it.

Why did you close that period?

I once met a guy in Asia, in Bangkok, who'd been a correspondent for a Spanish newspaper in the 70's and he was an old alcoholic, frequenting prostitutes, etc. He was telling me about his life and I was thinking: one day I'm going to be like this guy. And I told myself I didn't want to end up like that. From the very beginning, I tried to create another parallel part of my life to retreat to when the time came. I always knew I'd leave, that one day all that would come to an end. We're usually told that human beings are good and that the world makes them bad. I think it's the other way round. Human beings are born with instincts that aren't bad, but very primal: keeping warm, eating, procreating, sheltering, protecting ourselves. That's what we sacrifice everything else to. It is society that, by creating a series of rules, civilizes us. But put us in extreme situations and the human being becomes very dangerous.

Sidi is a charismatic warrior who gets his supporters to follow him blindly into battle and brings about cohesion and understanding among very diverse people. For example, Moors and Christians united under him. What qualities do you think a leader should have? .

In a way, this book is also a kind of self-help manual on leadership. My idea was: why does a member of the lowest rank of the nobility who has fallen from grace into disgrace, a nobody to all intents and purposes, manage to become a legend who eclipses the names of the kings of his day? How does a man, at that time, get others to follow him and die for him? How does he achieve such loyalty, loyalty being the hardest thing to achieve in life? And I wasn't interested in him as the finished article but rather in when he began to become the Cid: the years of evolution, of exile; in short, when the legend begins.

Are there leaders today?

Yes, possibly. There always have been. But the problem, in my opinion, is that our times don't deserve these men. When we speak of virtue in the Roman sense, namely, of nobility of spirit and an elegant attitude towards life, of personal dignity and courage, you realize that today's world is not interested in that, doesn't want it and even rejects it. What's more, when the people of today come face to face with virtue, they mock it. Up against noble people who can't be matched, they ridicule them. The mediocre person tries to bring them down. And since they can't, they try mockery. Anyone can do it over the Internet, in 140 characters, on TV...

Laughter is a powerful weapon ...

The Cids, the personalities are there. Human beings constantly produce geniuses, artists and creators, heroes and firefighters, wonderful people willing to die for many reasons. They're people willing to sacrifice themselves for what they believe in. That bothers some people.

Do you think there's anyone left now who's willing to die for their country or an ideal?

Actually, I don't think the Cid dies for an ideal. He had a code of allegiances and dignity. I mean, what I was interested in highlighting about the Cid is that it's not about a person who sets out to fight for an ideal. He was doing it to put food on the table. He is not fighting first and foremost for the Reconquest (which didn't as yet exist in Spain) but rather because these were kingdoms where there was fighting between Moors and Christians. Besides that, he has no providential mission. All of that comes later. He had no religious or patriotic ideas, which is to say, he wasn't fighting for God or country.

But despite his banishment, he continued to pledge allegiance and respect to King Alfonso VI.

Do you know why? Because when you have nothing, when you are an outcast, expelled from the bosom of society – whether you are a criminal or a mercenary – and the general codes with which society protects itself stop working, you need to have something to respect: you need a loyalty code between your people and something else. Even marginalised people, even people who are moderately decent seek some kind of justification in order not to feel wretched.

In your book The History of Spain, you wrote your version of it. For many people, it’s a cliche to say that Spain is different. Do you think so?

Yes, of course, Spain is a very rough and rugged country divided up into plots and land parcels where, when a valley meets its neighbouring valley, they suspect each other. We've always had that kind of geographical fragmentation. To that we have to add the Muslim invasion, religions, bad governments, etc. So Spain has a long history of discord, lack of unity, villainy and Cainism. I've always said that Cain had a Spanish ID card. And when you analyze the history of Spain, it becomes clear that, with that lack of solidarity, it is difficult for us to do anything in unison. As soon as the pressure gives way, everything disintegrates. So, the best thing for a Spanish child is to make them travel, because if you leave them in their valley, in their village, they will never leave. In Spain, any control over education has been lost. It's chaos. There are gaping holes in culture, the arts, etc. There are seventeen different systems ... and that doesn't leave much hope as regards future generations.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Interview with Arturo Pérez-Reverte - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Stephen Schwarzman (Pennsylvania, 1947), CEO and co-founder of Blackstone, one of the world's leading investment firms, is an active philanthropist in areas such as education, culture and the arts. He recently published his memoir: "What it Takes". Since his youth, Schwarzman has been a courageous, self-confident man with a spirit of leadership and ambition whilst being careful not to be reckless. With a BA from Yale University and an MBA from Harvard Business School, he is a tireless worker who barely sleeps, knows how to select the best people, listens to and asks for advice and always finds time for a kind word.

Author: Elena Cué

Stephen Schwarzman.

Stephen Schwarzman (Pennsylvania, 1947), CEO and co-founder of Blackstone, one of the world's leading investment firms, is an active philanthropist in areas such as education, culture and the arts. He recently published his memoir: "What it Takes". Since his youth, Schwarzman has been a courageous, self-confident man with a spirit of leadership and ambition whilst being careful not to be reckless. With a BA from Yale University and an MBA from Harvard Business School, he is a tireless worker who barely sleeps, knows how to select the best people, listens to and asks for advice and always finds time for a kind word.

Blackstone, the world’s largest alternative assets management firm, which you co-founded with Peter Peterson in 1985 with $400.000 start-up capital, is now worth $55 billion with $500 billion turnover. What do you think is the key to its success?

To begin, we had a really good strategic plan. One thing I have learned in life is that you need to know where you want to go and you need to have a good plan. You need to do something that nobody else is doing, something you think will become very popular and develop very big ideas. Our strategic plan had three parts. The first was to go into the Merge and Acquisitions Advisory business (M&A). The good thing about this business is you do not need any capital. Large corporations pay you millions of dollars to think and advise them. If they pay you, it is because you are doing it well.

The second part to our strategy was to go into the private equity business which basically consists of buying companies, improving them and making them grow faster, which in turn will make them sell better or go public. They will have more income and therefore double the profit. That way you have transformed the company into a much faster growing business and you will hire more people. It is very beneficial. You can end up making double the profit by investing in the stock market averages. If you double it, a lot of people will want to give you money so they can make double too.

Where does the capital come from?

Generally, we get our money from very big pension funds around the world, but we also receive investments from other institutional or individual investors. We thought this type of business would have explosive growth and it has. The key was finding people with talent in that area, a great investment potential. That was the third part to our strategy.

And how did you become the biggest Real “Landlord” in the world?

At that stage, we could not foresee what the areas of interest would be. Therefore, we had to wait and that is precisely how we ended up in real estate in 1991. We saw an opportunity in the real estate sector during the second US government auction in which a lot of bankrupt savings and loan types from banks were on sale. Now, we are the largest real estate owner in the world. We specialize in buying in places which have had difficulties so the price drops significantly and then with the normal economic recovery comes a large profit.

So they began to grow...

We invested in improving those assets in order to make them more attractive. That is the basis of how we built the firm. In 1986, we started by raising our first fund and now, instead of one, we have 50 funds in 50 different areas. We began in the United States, then expanded to Europe and Asia. We started with the highest returning products and now we have realized that products with less return and less leverage are also attractive.

In the last few years, you have invested €23 billion in our country. What lead you to invest in Spain?

Spain played an important role in Blackstone’s development. Our team discovered Spain was building so many apartment units they could have housed most of Germany and still had units left over. It was easy to predict that the construction sector would end up collapsing. At the same time our team in India informed us that land prices had multiplied by 10 in 18 months. The same was happening in the United States. Therefore, I told my team we had to sell all the assets tied up in residential housing around the world. It was clear what was going to happen.

It seemed like not everyone was aware of it...

Our business consists of gathering information and objectively assessing it. When Spain, as expected, went through a very difficult economic time and nobody in the country was buying real estate, we thought if we could buy properties at a low enough price and invest in improving them, we would achieve excellent results, as was the case in the United States. Indeed, that is what happened. Spain is a strong country despite having gone through a terrible time with the crisis. We believed in Spain and its ability to recover.

How would you evaluate the current economic climate in Spain and in Europe?

Spain has recovered very well. It has a good economy. Europe is experiencing a deceleration in terms of economic growth, as is every country in the world.

Some say another recession is on the horizon.

I am not sure we are going to have a recession in the United States, it is more likely to happen in Europe. The United States is doing better. There is full employment, the best rates since 1969. The American consumer is very strong. Wages are increasing faster than inflation so consumers have more money and they are spending it. That represents 70% of the US economy. That is the base. Even though manufacturing all over the world is decreasing, including in the United States, it only represents 11% of our economy, in comparison to 70% made up by the consumer, which is a vast difference.

Stephen Schwarzman. Photo by Elena Cué

In your book “What it takes” you talk about the mentors who shaped you as a person, such as, your father. Which values laid down the foundation of your career as an entrepreneur?

In the United States it is quite common to help others in their professional career. Most entrepreneurs are not completely alone, they often have partners, particularly in the field of technology, where most of the great companies were formed by various people. I was going to drop out of my MBA program at Harvard. I wrote a letter to the manager of the company I had previously worked for and he responded with six pages about his life. After reading it, I said to myself: “OK, I will continue studying”. That one decision changed the course of my life. There are many times when there is a point of inflection. You talk to other people and if they are intelligent, you listen to what they say and act accordingly. This helped me so now it is my duty to help others.

What are the most relevant attributes a person must have in order to join the Blackstone team?

Blackstone has always been what we call a meritocracy. It means that the people with the best values win; we are looking for born competitors. We keep producing new business lines so everyone can be in charge of something if they are qualified to do so. We are looking for people who are very intelligent, hard-working, non-political and good communicators. People who have a good understanding of what is happening around them and also possess solid analytic skills. Another attribute is they must be good people. When I was at Lehman, there were a lot of employees who left a lot to be desired in that aspect which lead to a very talented group of people suffering.

What would you advise someone who wants to start a business?

You should try to do something that no one else is doing, imagine something that does not yet exist but you think the market will want. If you limit yourself to opening the exact same type of business as others, there is no real reason why anyone should come to you. It becomes much less likely you will be successful, it is not bad, but it is not ideal. You have to time it right, without deviating much from what people want. When Walt Disney created his first theme park, he knew exactly what he wanted to do. No one else had done anything similar until then. There is always a myriad of setbacks, but moving forward and overcoming those problems is not as important as having a clear vision of what you want to do. The creative process is initially abstract; it is just a thought. Then you need to assemble as many financial resources as possible. If you have big dreams, the chance of them coming true is a lot greater.

In the book you explain how President Donald Trump asked you to form and manage a group of talented and knowledgeable individuals, no politics, who could tell him the truth. The Forum was later disbanded. It seemed to be a very good idea for any government…

Everyone who runs an organization should aspire to have as much objective input as possible. When you are the head of something, particularly in politics, you are quite isolated because when people around you criticize you, you usually stop listening to them. Forming a group of people, who are not political, who tell you what you are doing right and wrong, is a great concept. In a democracy, most people are not necessarily experts in everything, yet they are responsible for everything. Would it not be useful to have experts to guide you in the areas you are not familiar with?

You have served your country in many ways, including acting as the intermediate in trade talks between the United States and China. What is your opinion after the United Nations’ last General Assembly?

It is complicated because the Chinese have adopted an emerging market approach to their economy, much like the United States did in the 19th century when it was a developing country. At the time, we relied on significant tariff barriers that allowed us to develop our economy protected by those restrictions. China is experiencing the same process. Forty years ago, the average income in China was only a few hundred US dollars per person, whereas currently it is around $10,000 per person. Today, China is the second biggest economy in the world, after the United States. There is a big gap between China and other countries. Together the United States and China represent somewhere between 35% and 40% of the whole world’s economy, depending on the scale you apply. The United States and the developed world want China to remove some of these restrictions that confers them certain advantages over other developed countries. It is difficult for China because if you have always had an advantage, why would you change? In which case, they haven’t. It is not a coincidence that we have not signed an agreement with them in about 70 years. Now we are taking that very seriously.

The lack of trade agreements for such a long time is surprising. Could you explain some of the causes behind the lack of understanding between the United States and China?

There are two groups in Chinese politics: the reformists who believe China should adjust and change, and the intransigent people who are satisfied with what the country has done and do not want to change it. The reason why trade agreements are so difficult is because it is hard to know which part of China is going to control the country’s demands. At different points of the negotiations, the power shifts back and forth between the reformists and the intransigents. Negotiations between the two countries were about 90% complete in May this year but the Chinese then eliminated about a third of what was agreed and the negotiations collapsed. I think both China and the United States realize that decoupling the two largest economies on the planet is going to slow the world down and not just in the short term. It is probably in the best interest of both economies to establish their objectives.

How did China become important to you?

Actually, it all happened by chance. In 2007, when we went public, the Chinese government approached us to request to buy 3 billion dollars worth of stock, which represented 9.9% of the company. We offered them non-voting stock which meant they would not have a member on the board of directors. It was the first time since 1949, when modern China was founded, that China as a country, had bought a major amount of shares in a foreign company. Blackstone was the first. This had global repercussions because it was a sign that China had started to recycle its huge financial reserves and wanted to participate in the rest of the world. For us it was a complete surprise.

In 2016, you founded and built the Schwarzman Scholars College at Tsinghua University in Beijing, which offers a master’s program helping to build a stronger relationship between China and the rest of the world. What was your motivation?

Current president Xi Jinping and his predecessor studied at Tsinghua University, the biggest politically connected university in China. It has an international advisory board formed by a group of CEOs from different countries, including a lot of prominent Chinese figures such as Jack Ma from Alibaba, Robin Li from Baidu, Pony Ma from Tencent and people from around the world such as Tim Cook from Apple and Mark Zuckerberg from Facebook, amongst others. There are also many senior members of the Chinese government. I could see that things were not going to remain the same between China and the rest of the world after the financial crisis because China continued to grow, whereas European countries and the United States went into a terrible recession and unemployment in Europe is still very high. That situation would lead people in the developed world to feel unhappy, particularly those who earnt between 40% and 50% of the average income and generally, that triggers what is known as “populism”. People in lower income brackets get angry with the wealthy and with business and financial people. Normally, as shown in history, they project their anger onto a foreign devil and I knew, in this case, it would be China because it was very important. China was doing so well both economically and financially. Therefore, I decided I wanted to address this problem of the Western world’s friction with China.

In June, your record donation of £150,000,000 given to the University of Oxford was announced and featured on the front page of all the major media sources. Can you explain the main reason for such a generous donation to the field of ethics in Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial Intelligence is a new technology which will explode all over the world as it can do some incredible things. It can help enormously in the medical sector, in education and in the workplace. It is a revolution. On the other hand, AI can create problems. One area is employment. Machines will replace people, as they already did at the start of the industrial revolution but that took about 100 to 125 years, whereas AI will happen in the next 10 to 20 years. The idea that everything always works out is right but if it happens very quickly, you can have huge dislocations and much larger unemployment than society can absorb. Therefore, Artificial Intelligence ethics is just a code word for trying to figure out how to allow this technology to be introduced to society so we can reap the benefits, whilst maintaining enough control to ensure the disadvantages are reduced. This requires the involvement of governments, companies, research universities and the media so that you can introduce these regulations without eliminating the benefits of the technology which will enormously help all kinds of people. That is why I am supporting this. I chose Oxford which is a unique university in the study of humanities.

With a donation of $350.000.000 you have created a new space in Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) dedicated to the study of Artificial Intelligence and Computing which will be opened this year.

The reason for creating the Schwarzman College of Computing at MIT is to advance in the field of science but also to analyze AI ethics. Oxford is number 1 in humanities in the world, whereas MIT, depending on whose ranking, is number 1 or 2 in technology in the world. I dedicated a lot of time and financial resources into this because I think it is very important for humanity.

What does it mean to you to be the chairman of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C.?

During President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech in 1961, he said: “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” In my generation, we were expected to help our country. When I was asked to take on the Kennedy Center job, I thought it would be a good thing, because I could help. I did not want to go into government full time. I had been asked to do that before but I did not want to.

In addition to the previously mentioned, you have also made other significant donations to the New York Public Library ($150m), Metropolitan Museum and Yale University ($150m), a football stadium... What is your understanding of philanthropy?

I am involved in different types of philanthropy. I like creating very large-scale projects that have never been done before, consistent with my book. I do the same with philanthropy. I ask myself if there is something I can create to help resolve a big problem. Actually, I do not really consider it philanthropy. I start by asking: “What is good for society?” before backing into important financial commitments. Together with my wife, Christine, we have ended up being the largest donors to Catholic schools in the United States. I am not Catholic but the schools are great. Only about 50% of the children who go to these schools are Catholic: 90% are minorities, 70% are on the poverty line or below and 98% of them graduate.

Stephen Schwarzman during the interview with Elena Cué

- Interview with Stephen Schwarzman - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Francisco Calvo Serraller

Let me start by highlighting what makes the 'Lorenzo Lotto. Portraits' exhibition such an exceptional project. Firstly, because never before has this subject been featured in a monographic exhibition; secondly, because this is the first ever time an exhibition of the great Venetian artist's work has been organised in Spain, which has only one of his paintings on display, here at the Prado; thirdly, because it comprises almost fifty works, some of them among his best; fourthly, because, although Lotto's main focus was, as the exhibit title would suggest, the genre at which he excelled ~ portraiture, a substantial complementary space has been added to showcase his uniquely personal and beautifully rendered religious painting; and finally, for its splendid presentation and staging at the reputable hands of Jesus Moreno. And as if all that were not enough, it is also worth mentioning with regards to the venue that this inauguration coincides with two other first-rate exhibitions, namely 'Rubens. Painter of Sketches' and 'In lapide depictum. Italian painting on stone 1530-1550", constituting a trio of internationally unmatchable calibre at the Prado.

|

Dr. Francisco Calvo Serraller, writing exclusively for Alejandra de Argos |

|

Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia (1530 - 1533). Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 110.6 cm. The National Gallery, London

Let me start by highlighting what makes the 'Lorenzo Lotto. Portraits' exhibition such an exceptional project. Firstly, because never before has this subject been featured in a monographic exhibition; secondly, because this is the first ever time an exhibition of the great Venetian artist's work has been organised in Spain, which has only one of his paintings on display, here at the Prado; thirdly, because it comprises almost fifty works, some of them among his best; fourthly, because, although Lotto's main focus was, as the exhibit title would suggest, the genre at which he excelled ~ portraiture, a substantial complementary space has been added to showcase his uniquely personal and beautifully rendered religious painting; and finally, for its splendid presentation and staging at the reputable hands of Jesus Moreno. And as if all that were not enough, it is also worth mentioning with regards to the venue that this inauguration coincides with two other first-rate exhibitions, namely 'Rubens. Painter of Sketches' and 'In lapide depictum. Italian painting on stone 1530-1550", constituting a trio of internationally unmatchable calibre at the Prado.

Portrait of Andrea Odoni (1527). The Royal Collection Trust, London

Moreover, Lorenzo Lotto's biography and subsequent destiny of critical acclaim are a constant source of interest. A native of Venice itself whose exact date of birth is unknown but is estimated by experts to be around 1580, our grand master's training and career start could not have been more brilliant, having as he did rolemodels such as Giovanni Bellini, of whom he was reputedly a direct disciple, along with Giorgione and Titian but he was also influenced by Antonello da Messina and Albrecht Durer, a manifestation of the great significance and variety in the configuration of his own particular style.

His early days as a professional in Venice were met with notable success and the promise of great things to come but the stiff competition with other local masters such as Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese, all of whom were endowed with a more pugnacious and business-minded temperament than his, left him with no other alternative than to seek his fortune outside the closeted enclave of the Republic's capital, in the comparatively minor cities of Veneto and neighbouring areas. In this way, Lotto managed to make ends meet with varying degrees of success and, as can often happen in the course of anyone's life, with the passage of time his star waned, only for him to end up as an oblate in Loreto, not knowing where else to live out his last days.

Portrait of a Young Man (1530 - 1532). Oil on canvas, 98 x 111 cm. Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

Then and now, the reality is that very few artists are able to make a living from their work alone and fewer still if we look back at the past because, until recently, neither were there many other options if luck wasn't on your side. In this sense, Lotto's own personal frustrations cannot be taken as exceptional and neither can the fact that at the time of his death he had not received the recognition he deserved. In actual fact, recognition of his memory and work had to wait until the 20th century when Berenson revised and raised the profile of the hitherto disdained painting of 15th century Italy but, ultimately, he didn't receive proper public acclaim until the latter stages of the 1900s. And in some ways, this widespread recognition of his oeuvre is very recent indeed, as demonstrated by this exhibition which, as previously mentioned, is only the first ever in Spain as well as being the first in the world to monographically showcase his portraiture, a genre to which Lotto made outstanding contributions. These are evidenced in the only painting of his owned by the Prado, a novelty at the time in Italy for depicting a newly-wed couple, as can be seen in the various heraldic elements. Obliged on this occasion to use a landscape format, Lotto continued to do so with individual portraits which gave the subject much greater spacial freedom and the possibility of encompassing a wider horizon. In any case, what is so extraordinary about the quality of Lotto's portraits is not limited just to their format. There is also an effect on composition, psychological aspects, his astute judgement as to the symbolic use of circumstantial details to identify the personality, rank and office of the sitter, the beautiful way he paints hands, among many others. Whatever the case, the result is that Lotto's portraits seem so modern that their impact is perhaps greater now than when they were painted because they give us the impression that their physiognomies and expressions are the same as ours. Whilst true that during the first half of the 16th century, at the height of Mannerism, this type of painting that we are so fond of today proliferated, and notwithstanding other brilliant portraitists of the time, Lotto stands out. There are a selection of his best and most well-known here at the exhibition, for instance Portrait of a Young man with a Lamp (c. 1506), Andrea Odoni (1527), Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia (c. 1530-33) and Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1530-32) but there are also others of equally high quality albeit not as popular as the aforementioned, from the very early Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1498-1500), still heavily influenced by Bellini but with eyes and mouth that show a profound psychological insight, up to and including Bishop Bernardo de Rossi (1505), Portrait of a Young Man (c.1512-13), Lucina Brembati (1520-23), Portrait of a Young Man with a Book (c.1525), Portrait of a Gentleman (1535?), Portrait of a Man with a Beard (c. 1540), Portrait of a Man with a Felt Hat (h. 1541) or Portrait of an Architect (c.1540-42), to mention but a few of many outstanding pieces.

Portrait of a Married Couple (1523 - 1524). Oil on canvas, 96 x 116 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

But in addition to this magnificent display of portraits, the exhibition also includes other genres in Lotto's repertoire and, in particular, his religious painting where delicate, stylised figures writhe in space as in a harmonious ballet, their body language dramatized in studiously-arranged twists and turns and the scene as a whole is wrapped in a chromatic sheen of glossy satin where colours contrast with each other in original and imaginative ways. This added bonus is an essential complement in a country like ours where the work of this Venetian painter is only being exhibited monographically for the very first time.

Lastly, and in another contribution to the ensemble, there are display cases containing various textile and gold or silver objects that don't just illustrate the dress and jewelery of those memorialised in the portraits but also explain their function within the narrative, thereby demonstrating that we are not just viewing a presentation of Lotto's paintings, but rather we are seeing an interpretation of them, and in many cases a novel one at that. It is interesting that, in this regard, the focus is on portraits where the subject is represented as an incarnation of the ideal of holiness, a burning issue at the precise moment in history when the ideological battle to control and censor images was at its peak.

The Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Anthony Abbot and Louis of Toulouse (1506). Oil on panel, 175 x 165 cm. Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, Asolo

This exhibition, which after its run at the Prado will move on to the National Gallery in London, has been curated by Enrico Maria dal Pozzolo y Miguel Falomir, in collaboration with Mathias Wivel. All of them deserve to be congratulated on their splendid work, along with the layout and arrangement of the pieces, not forgetting the beautiful and informative catalogue which, in this case, is an indispensable complement to the exhibition.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- The wonderful rediscovery of Lorenzo Lotto - - Alejandra de Argos -