- Details

- Written by Pedro García Cuartango

Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, argued that man lacks essence and is condemned to be free. Jean-Paul Sartre was a man of many parts: philosopher, novelist, playwright, literary critic and political agitator. But he was, above all else, someone who made the absolute most of a life that was intense.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, argued that man lacks essence and is condemned to be free.

Jean-Paul Sartre was a man of many parts: philosopher, novelist, playwright, literary critic and political agitator. But he was, above all else, someone who made the absolute most of a life that was intense. His open relationship with Simone de Beauvoir has passed into legend but Sartre, the most influential intellectual of his time, was also the father of existentialism and of a new way of looking at the world.

A French-born thinker, Sartre would become the icon of an era. There are photographs of him in basement jazz clubs with his friends Juliette Gréco and Boris Vian, standing on an oil drum haranguing Renault workers or selling the first copies of Liberation on the streets of Paris. Never without his trusty pipe, horn-rimmed glasses and roguish, irreverent air.

It would be difficult to summarize thoughts as prolific and diverse as his but if there is one book in which a systemization of his philosophy can be found, it is “Being and Nothingness”, conceived in the midst of World War II and published in 1943. Sartre, who served as a meteorologist, did time in several German prison camps after the defeat of France.

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Five years earlier, he had written "Nausea", a novel in which he laid the foundations of existentialism. Its protagonist is Antoine Roquentin, a bachelor living alone and working on the biography of an aristocrat. The book is a description of provincial city life where daily routines confront him with the absurd fact of existence. Roquentin says: “The essential thing is contingency. I mean that one cannot define existence as necessity. To exist is simply to be there.”

This phrase expresses Sartre's philosophy better than any other. The basic idea is that Man lacks essence, he is pure existence. We are not born with a specific nature nor are we part of a project. We are pure indeterminacy. We build our identity as we go, based on our actions.

Heavily influenced by his reading of Husserl, Sartre will go on to point out that consciousness is intentional, or in other words, it always indicates something. There is, as such, no self-awareness. What there is is a perception of others, through which we become aware of who we are.

As opposed to Hegel and Kant, Sartre argues that being is an appearance: it is what it seems or, better still, what it appears. But there is a being in-itself, which are things and the exterior world, and a being for-itself, which is the process through which the subject is built through the exercise of freedom.

As we as human beings harbour an emptiness within us (which Sartre calls nothingness), we are condemned to be free. This is the only determination with which we are born - the imperative to assume our own decisions. To exist is to choose. We must act according to our own rules.

In a few words that call to mind Kierkegaard, Sartre asserts that our anguish comes from the radical freedom with which we have been thrown into the world, from the need to choose between the multiple choices that present themselves at each and every moment. This exaltation of freedom is incompatible with the existence of God, which is a sublimation of reason. "Man is nothing but what he makes of himself," he says. For the same reason, Sartre turns away from both romanticism and psychoanalysis, which he considers a mythification of feelings.

More than an ethic, existentialism is an aesthetic that underlines the precariousness of man and the absurdity of existing. But it is still no less of a paradox that Sartre enjoyed life immensely with his love affairs, his fondness for alcohol, his sense of friendship and his travels.

From the 50s on, Sartre became increasingly politically radicalized, aligning himself with Maoism, Cuban socialism and, later, the May 68 movement. Although never a member of the Communist Party, he was a sympathiser on many causes, albeit always keeping his distance from Stalinism. In 1960, he wrote a controversial treatise entitled "Critique of Dialectical Reason" in which he attempted to liken existentialism to Marxism, an impossible endeavor.

Sartre's political shift pitted him against Albert Camus as both favoured opposing solutions to the Algerian War of Independence. The former sympathized with the rebellion against French colonization and the latter condemned the terrorism of the independence fighters and advocated for a political settlement. They would never be reconciled. There was no time to as Camus killed himself in 1960. Sartre would outlive him by two decades.

To his credit, it must be remembered that Sartre was never impervious to the great debates of his day. He was often seen at rallies, street protests and action in defence of minorities. He held his peace about nothing. He believed that the intellectual's obligation was to be present and to make heard a voice that still resonates with us today.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

Jean Paul Sartre on Intellectualism

Camus vs. Sartre

- Jean-Paul Sartre. To exist is to choose - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

It has been 62 years since a young artist, recently arrived in Paris having fled from communist Bulgaria stowed away in a train carriage, began painting sketches with the dream in mind of one day wrapping the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. That young visionary along with Jeanne-Claude Guillebon, his wife and other half in life and in art, are no longer with us, she having died in 2009

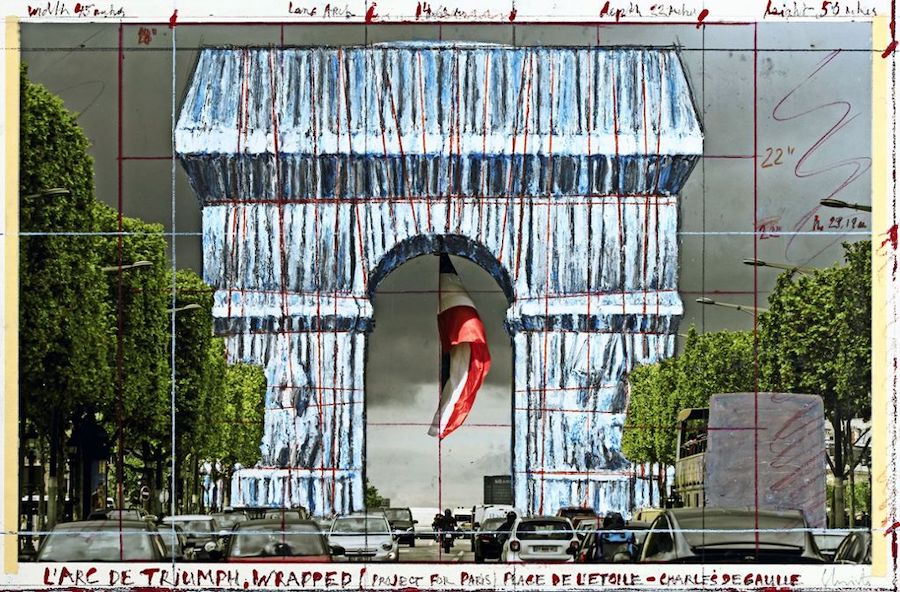

Preparatory drawing for the Arc de Triomphe installation in Paris (2019)

It has been 62 years since a young artist, recently arrived in Paris having fled from communist Bulgaria stowed away in a train carriage, began painting sketches with the dream in mind of one day wrapping the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. That young visionary along with Jeanne-Claude Guillebon, his wife and other half in life and in art, are no longer with us, she having died in 2009 and he on 31st May 2020 in New York, shortly before his 85th birthday. But this coming 18th September, and over 16 days, the Arc de Triomphe will, at last, be veiled in 25,000 square metres of silver blue fabric fastened with three kilometres of red ribbon rope. Everything had been measured out, drawn up and written down by its creators.

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff was born on 13th June 1935 in Gabrovo, Bulgaria and that same day in Casablanca, Morocco, Jeanne-Claude Guillebon was born. Above all else, Christo and Jeanne-Claude symbolise a love story that lasted the entirety of their lives. Between 1953 and 1956, he studied ‘Socialist Realism’, as mandated by the state, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sofia. He was so precociously and highly gifted a draughtsman that his mother insisted he have drawing lessons from the age of six. He fled communist Bulgaria in 1957 for Paris, a city that he had chosen as his destiny from the outset. There, he made ends meet for the first few years by painting portraits of the upper classes. In March 1958, a few months after his arrival, he met Jeanne-Claude who came from a military family with little connection to the world of contemporary art but who adapted to his life with enthusiasm, intelligence and passion. From 1961, they began working together and, this same year, on the occasion of their first solo exhibition in Cologne (Germany), they mounted their first temporary installation at the city’s port. Christo, at that time in the grips of an obsession, was wrapping everything up, even his wife's high heels. Those pieces would become the catalyst for the spectacular environmental interventions we know today. As of 1964, they settled in New York.

Christo and Jeanne Claude in their New York studio with sketches of Surrounded Islands in the background (1981)

Jeanne-Claude's contribution has often been described as the mere administration of contracts and sales yet it was much more than just that. Such was the passion both she and her husband felt for their joint work, they would travel on different planes so that, in the event of one’s crash, the other could continue to fulfil their destiny.

They dedicated more than 50 years to encasing landmarks and landscapes in cloth - ephemeral works that captured the imagination of the whole world. However, Christo has said that they never thought about the impact their work would have on generations of artists to come - a humble claim for a legacy like theirs, among the first artists ever to leave traditional gallery space and take their work as far away as the Australian coast and the German parliament. They wrapped valleys in curtains, covered islands in drapes and braided fabrics between bridges. Nothing seemed unconquerable.

Surrounded Islands, Bay of Biscayne, Florida (1980-1983)

The profound and loaded significance of the word "freedom" was undoubtedly the beacon guiding all their projects and the key to their work as well as their lives. "I was really drowning in that horrible Soviet regime. I couldn't give up an inch of my freedom," Christo said. "All these projects are completely irrational, completely useless. No one needs them. They can’t be bought. They exist in their time, impossible to be repeated. That is their power."

In order to explain their work, former refugee Christo has said that he considered all of their creations to have been marked by nomadism. "The fabric is the main element to transmit this. The projects have many complex parts but the fabric is a quick thing to assemble, like the Bedouin tents in nomadic tribes."

The Gates, Central Park, New York (February 2005)

From their home in New York shortly before his death, Christo stressed that their works, despite being temporary, are not performances - they are sculptures that cannot be owned. In that sense, he mocked the art market and its most recent, grandiose productions. Granted, all of the preparatory drawings and materials have been put up for sale over the years but self-financing was always their sole modus operandi. Despite each work requiring huge sums of money and employing hundreds of people, this allowed them to fly free and far from the bonds of any concessions, impositions or patrons.

Running Fence, Sonoma, California (September 1976)

The only dues Christo and Jeanne-Claude incurred were in the form of the permits they had to obtain - bureaucratic battles lasting years and taking its toll on many of their illusions, but Christo thought this journey helped gestate their pieces: "The work of art reveals itself little by little throughout the process of getting permits." Many attempts failed. Despite Jeanne-Claude's gift for negotiation, 23 projects saw completion over the years but 47 did not.

Among the projects they did succeed in realising was 1983's "Surrounded Islands", eleven of them ringed by rivers of pink cloth in Miami’s Biscayne Bay. Also in 1985, they completed their first major project in Paris - covering the capital’s oldest bridge, the Pont Neuf, in fabric after many months of dispute with the mayor at the time, Jacques Chirac, as detailed in the fascinating documentary "Christo in Paris".

Pont Neuf, Paris (1985)

Between 24th June and 7th July 1995, their then most ambitious work, “Germany”, was installed in Berlin. In the space of two weeks, five million people from around the world came to see the Reichstag wrapped. This installation transformed the seat of German politics after its reconstruction by Norman Foster who added the famous glass dome. Christo and Jeanne Claude had fought for 23 years to get the permits and on 23rd June, the plastic panels shielding it were removed - some 100,000 metres of fabric tied round with ropes one kilometre long to make the outline of the building visible. Christo said that, until 1989, the Reichstag had been a mausoleum, a sleeping beauty that they had reawakened. The building fascinated him as a symbol of freedom and its wrapping proved to be an astonishing feat of technology. David Bourdon, Christo's biographer, defined the Bulgarian artist's philosophy of art as "revealing something by hiding it."

Wrapped Reichstag, Germany (July1985)

After the Reichstag would come "The Gates" (2005), a 23-mile route through New York's Central Park dotted with 7,503 doorways hung with saffron-coloured panels blowing in the wind. And, more recently, "Floating Piers" (2016), comprising three kilometres of floating pontoons on Lake Iseo (Bergamo, Italy).

Arc de Triomphe, Place de l’Étoile, Paris (1963)

At the time of his death, Christo had another project in the pipeline – the wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, an intervention that had to be postponed until September 2021 due to the outbreak of Covid 19. Concurrently, the Pompidou Centre held an exhibition dedicated to the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude and focusing on their French projects.

The plans for the Arc de Triomphe were approved in just one year: "Thank you to the young President," said Christo, referring to Macron, but when asked if this was a sign of greater understanding and acceptance of his work in France, he replied with a loud and unequivocal "No!" and went on to explain that "For each project, we have a thousand people trying to help us and another thousand trying to stop us". Running in tandem was an exhibition at Madrid’s Guillermo de Osma Gallery paying tribute to this marriage of artists and featuring fifteen drawings associated with Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installation projects.

Preparations for L'Arc de Triomphe Wrapped, Paris (20 July 2021)

The Arc de Triomphe, with its huge historical significance, was built between 1806 and 1836 to celebrate France’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz under Napoleon’s command and fulfilling this promise to his men - "You will return home through arches of triumph". Measuring 49 m high and 45 m wide, it was designed by Jean Chalgrin along with Jean-Arnaud Raymond and inspired by the Arch of Titus in Rome. It sits on a hill crowned by the Place de l'Étoile from which radiate twelve avenues designed in the 19th century by Baron Haussmann. The historic war portal, with its iconic bas-reliefs and famous "The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792" sculpted by François Rude, will see its old silhouette spruced up for 16 days. Twice as many metres of fabric as its surface area will be used: "What we propose is a new structural dimension thanks to this beautiful fabric," Christo said. A project of this magnitude will require the labour of around a thousand people and "It will not be something static; it will be like a living being which will move with the wind; it will not be something made of bronze, nor bricks. It will be something that transmits the play of wind and sunlight," he said, inviting us to dream his dream.

Because what is compelling about these artists was their ability to force the spectator to become newly aware of an environment they had grown so accustomed to looking at, it had become invisible. It is by concealing it that it takes on the prominence it deserves. And so, now, Napoleon's Arc de Triomphe will once again be the arch celebrating another conquest - that of Christo and Jeanne Claude's work of wrapped art with its scaffolding nailed, this time, to the sky.

Christo & Jeanne Claude 1960-1970

Galería Guillermo de Osma

Claudio Coello, 4

Madrid

9 September - 15 October 2021

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- Christo & Jeanne-Claude: Wrapping The Arc de Triomphe - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

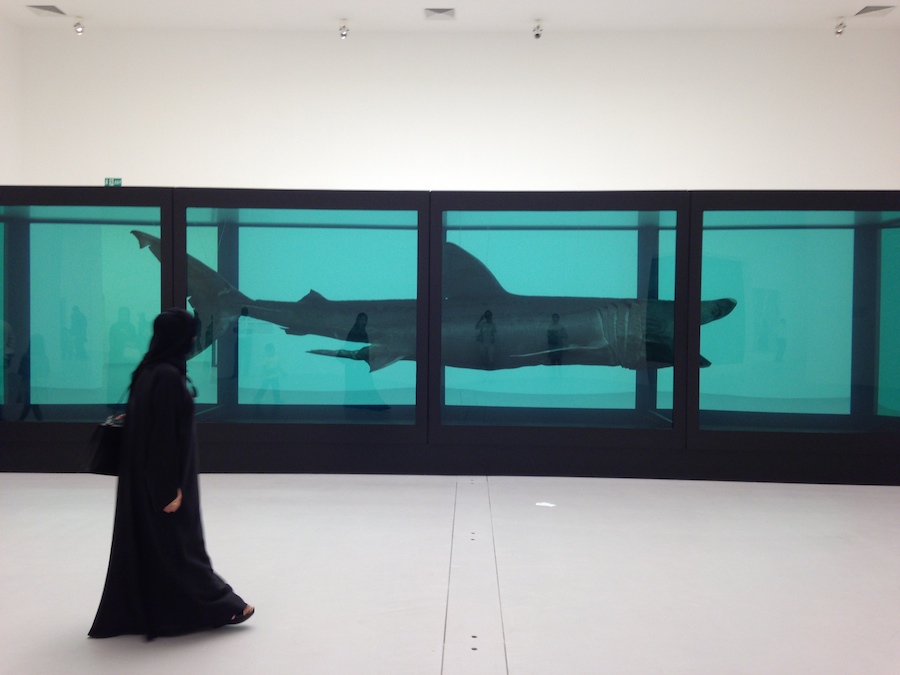

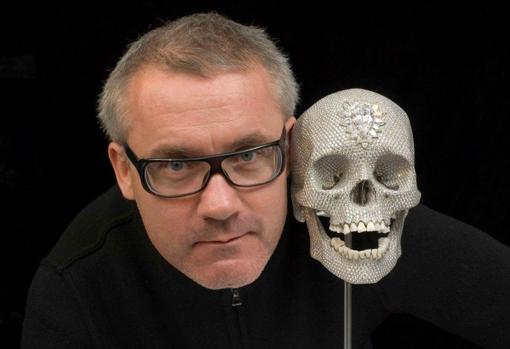

Damien Hirst (1965) began his artistic career as an iconic member of the Young British Artists group. The advertising mogul and gallery owner Charles Saatchi raised this group to the heights of world recognition and made Hirst its foremost representative, by funding and supporting his career. He was the one who managed to sell - in 2004 and for 9.5 million euros - Hirst’s tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. This particularly representative work forms part of his Natural History series, along with his cabinets of fish in formaldehyde.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

Damien Hirst (1965) began his artistic career as an iconic member of the Young British Artists group. The advertising mogul and gallery owner Charles Saatchi raised this group to the heights of world recognition and made Hirst its foremost representative, by funding and supporting his career. He was the one who managed to sell - in 2004 and for 9.5 million euros - Hirst’s tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. This particularly representative work forms part of his Natural History series, along with his cabinets of fish in formaldehyde. In these works, he sets a feeling of permanence, generated by his meticulous scientific organisation, against the ephemeral nature of life, which he also does with the minimalist style dissected cows and calves displayed at Tate Britain, which won him the prestigious Turner Prize in 1995.

Other important series of Hirst are his widely recognized Spot paintings: same-sized dots in random colours, named after pharmaceutical narcotics and stimulants. Or his Butterflies, named after a psalm that touches on Hirst’s favourite themes: life, death, art, beauty and spirituality. The mystery of death is shown through the final transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly, a symbol of the soul since antiquity, also seen in the rose and stained glass windows of cathedrals.

The Medicine Cabinets are yet another example of the philosophical concerns of Damien Hirst, an artist who has experienced the abyss of drugs, alcohol and tobacco, and who views art as therapy. Art, together with science is a social phenomenon of life in motion, a way of reflecting reality throughout history. In our current era, characterized by the triumph of technique, Hirst has succeeded in making his works into icons of contemporary art.

Alain Dominique Perrin, the creator of the Cartier Foundation, is holding Damien Hirst’s first exhibition in a French museum. We are referring to Cherry Blossoms, which displays 30 of the 107 works created by the artist over the last 3 years.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

You have recently gone back to painting. Has the fact your mother painted, in some way, determined your artistic career?

I suppose so, yes. Obviously, I already had a certain artistic instinct, but my Mum strengthened it when I was young, she encouraged me to draw and paint. I remember she would sit me in a corner with a pen and paper and when I would say I had finished the drawing, she would stick more paper to it again and again. Ultimately, I think it was a good thing, which helped me to think big.

At what age did you realise you wanted to be an artist?

It is difficult to say exactly when. I grew up in Leeds, Yorkshire, North of England, where nobody I knew was paid to do a job they enjoyed, rather, they would work for money doing any old job. For example, my Mum worked in an office and my Dad was selling cars for a big company. So, the idea was that a job was to earn money and your life was separate. With that in mind, because I enjoyed drawing, it never really occurred to me it could be a career possibility. I thought about becoming an architect as it allowed me to incorporate my passion for drawing, but it didn’t work. I was very messy when I was an architect. I signed on at the job centre when I finished my studies and that is when I had the idea to go to Art School. To be honest, the idea to become an artist came to me as a bit of a shock and it was only really at Art School that I realised it was a possibility.

At 16 you visited the anatomy department of Leeds Medical School to make life drawings. Death and decadence are themes that are repeated in your work. What meaning does death have in your work?

It is a complicated issue. I used to think that you could make art about death, but I don’t think you can anymore. Death is not art because art is life. I think I have changed as I have got older. As a human being, I want to confront things I can’t avoid. Death is one of those things. When I make art, I want to deal with those issues. That is the essence of art. Art deals with death. I think art is a light in the darkness.

Damien Hirst, Relics, Doha. Photo: Elena Cué

Can you tell me about your exhibition Cherry Blossoms at the Cartier Foundation in Paris and if the pandemic has affected your work in any way?

Absolutely, I think they are pandemic paintings. In my case, it got to the point where my work was very solitary. Before the pandemic, I dedicated 10 years of my life to Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, which involved working closely with many people, teams and fabricators. It involved very complicated things with different nuances in motion. After, I went on to paint with a few assistants. Then, I started working in a small interim studio just before Covid and when the pandemic hit; my assistants had to leave because there wasn’t any work. I began painting in solitary. Actually, I was very lucky to have the studio because when Covid came, I did not have to stop painting. Cherry Blossoms is a result of that. It is somewhat strange that such darkness brings such light and brightness. In reality, hope is one of the key aspects of the painting. When you are feeling hopeless... We have all felt and still feel great fear. Fear has a fundamental role when you want to make hopeful paintings. I honestly think it came out of that.

You studied Fine Arts at Goldsmiths College of Art in London. What was the most important thing you learned about art there?

I learned so much. One of the most valuable lessons was that there are no rules. Once I made something that was very confrontational and messy, I just screwed things together randomly. It was half-sculpture, half-painting, crazy thing. I remember the tutor saying it was not very good and I told her that that was the point. She then said that I needed to be clear with my work, to which I replied that was the point, I was not being clear. In the end, she agreed the only worthy artists are those who sack off everything for their convictions. In that moment I thought “That is it.” That was another key lesson. The teachers at Goldsmiths were all working, well-known, established artists. In many Art Schools teachers are failed artists who tend to teach what art means through a very negative perspective. That is why, studying at Goldsmiths was so incredible, there you were treated just like any other artist. From day one they trained you to go out into the world. They also taught you other aspects of the art world, not just its function. We were forced to justify everything and question everything. That was really important.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

In the 80s, you and some other students organised the Freeze exhibition, which caught the eye and financial support of the publicist and gallerist Charles Saatchi who, along with the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, elevated the group of Young British Artists. What did this collaboration mean to you?

There was a lot of exciting art at our college but there was not a place to fit it into the art world. We knew that no gallery wanted us, so we decided to create our own gallery. That was a turning point. We thought that we stood more chance as a group than every man for himself. It was a really exciting time. One of the lessons I learned at Goldsmiths is that you cannot paint, put your painting in a corner and wait to be discovered. You have to be more proactive. I wanted an audience and I had to find it. At Goldsmiths I realised you should not wait.

Do you miss collaborating with other artists?

I still have very good friends from those days. All the artists in that group were amazing, like Sarah Lucas, a phenomenal artist.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

Your admiration for Francis Bacon in your early days is well known. You stated that you stopped painting when you realised that your paintings were “like bad Bacons”. Which artistic technique do you feel most comfortable with now?

I enjoy painting a lot more now. I had a fear of painting. It was a question of confidence. There were two problems: one was a lack of confidence and the other was that painting was no longer fashionable and involved many challenges. Today it is very exciting, much more accepted. Back then painting was frowned upon, it was very old-fashioned, and I was desperate to be innovative and revolutionary which I could not achieve by painting. That is why I came up with the Dot Paintings, which ended up being very different from Bacon. In my heart lies the same kind of darkness that I really like in Bacon, Goya, or Soutine. Since then, I have managed to find my own way to paint, and I am very happy with that. I remember when I was a student, I used to paint and wonder about what people would think of my paintings. I would never really get involved. Whereas now, I just don’t even think about it. Someone once told me the real tragedy in painting is much more intense than that in real life. Just painting and playing with colours, I really feel the highs and the lows of existence. It is a new place for me, but I am very comfortable there. Just like Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable which is a very traditional exhibition, but it is actually very conceptual. Like my last show at Claridge’s, The Pipe Cleaner Animals, which I am very happy with. It is so childish, fun, and amazing.

Which part of the creative process excites you the most?

The end. I enjoy the technology, people, and machines but I like objects in an empty gallery.

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, Damien Hirst. Relics, Doha. Photo: Elena Cué

At the beginning of the 90s your work The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a shark submerged in formaldehyde, marked the start of your Natural History series, a totally revolutionary concept in the world of art. How did this idea come about?

Most of my ideas come from the desire to describe a feeling. I was looking for an object to symbolise a feeling. I had seen Richard Serra’s sculptures at the Saatchi Gallery. They were enormous steel sculptures. I remember walking between them, thinking they could fall on me at any moment. I remember feeling afraid and running out. I was fascinated by the fact that a sculpture could provoke fear. It invites you in to then terrify you. This was the root idea. I was inspired by a lot of minimalist artists like Carl Andre and Donald Judd. I loved Sol LeWitt’s Boxes (Project Box, 1990). I wanted to create a piece similar to that of Sol LeWitt but with something real at the centre. That is how the idea was formed. I wanted a real shark, big enough to devour a human and incite terror. Those were the ideas buzzing around my head and that is how this work came about.

Damien Hirst, Relics. Photo: Elena Cué

With the Medicine Cabinets series, you commented: “science is the new religion for many people”. What is your religion, what do you believe in?

My questions of belief have perplexed me for years. It is very difficult to find something to believe in and it is very difficult to live without having something to believe in. My exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable was specifically about faith and the search for truth in a world of lies. I was brought up in a Catholic family until I was 12 years old. Then my mother got divorced and she could not practice anymore. Right when she needed it the most, it let her down. That is why I gave up on being Catholic at age 12. With time, I realised that concepts like God are very complicated for me. I believe there is nothing. I prefer the scientific approach. I like science, but it fails in the same way religion does. Religion gives you almost everything you need. Money is the bane of religion. That said, my belief in art is almost religious. I believe in magic through art. Any kind of magic is a religious act. If you believe in goodness or in hope, if you believe that hope can conquer fear, you have religious thoughts. I believe in art, where one plus one can equal four, five, six, seven or anything. Thanks to art, you can create much more than you have. So, I suppose those are my beliefs. It is hard to say I do not believe in God. I believe in art because it is very similar.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

In science, what is allowed today might be the mistake of tomorrow. Science progresses but art doesn’t...

I think science offers an incredible way to view the world, but it is not the only one. In my opinion, it lacks the emotional part. We need emotions in order to survive. Scientists are not emotional enough and religions are the exact opposite. We need a mix of both. It is funny, both science and religion use art in the same way that governments do, to sell their ideas. There is no way to sell an idea without art. Just look at all the art that was made because of religion. Even in science, pills have to have the correct shape in order for us to believe in them because if each of them had a different shape, nobody would believe they have the same effect. Everything must be sterile and perfect, perfect shapes, perfect colours and perfect packaging in order for us to believe that science helps us fight against death. That is basically science. Science is a religion that declares it can stop death. In my opinion, science offers us immortality and religion offers us the afterlife. Although, in the end, they are both bullshit. As for art, it doesn’t offer you anything you do not have, it offers you something that already lives inside you. That is the difference between art, science, and religion.

Damien Hirst, Relics. Photo: Elena Cué

Walking in Paris, Cartier Fondation, Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, Paris 14th, july 2021

Damien Hirst, « Cerisiers en Fleurs » – Le film documentaire

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

- Interview with Damien Hirst - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

“I am a specialist in life as a permanent crisis.” Thus defines himself Miquel Barceló, one of the most sought-after and internationally recognized Spanish artists alive today. His capacity for communication goes hand in hand with the scope and variety of his work: huge canvasses, small drawings, murals, engravings, book illustrations, ceramics, sculpture, opera staging, album covers, posters, television programmes

The art of sea caves, the ocean and the soul

Miquel Barceló. Photo: Jaime García

“I am a specialist in life as a permanent crisis.” Thus defines himself Miquel Barceló, one of the most sought-after and internationally recognized Spanish artists alive today. His capacity for communication goes hand in hand with the scope and variety of his work: huge canvasses, small drawings, murals, engravings, book illustrations, ceramics, sculpture, opera staging, album covers, posters, television programmes ... Onto each and every one of those mediums, Barceló stamps his character, his energy and the "aggression" that distinguish his work - as well as his profound interest in Nature, whether that be in outdoor spaces or the life contained within them but always with a Mediterranean or African backdrop that connects his art directly with the land and the sea. His work is personal, original, complex and impossible to pigeonhole into any one artistic movement or context.

Adolescence, Nature and roots

"The Flood" (1990). Guggehneim Museum, Bilbao

Miquel Barceló was born in 1957 in Mallorca, a Mediterranean island where the young artist first experimented with art. The influence of his mother, who herself was a painter for a time, might have had something to do with his desire to create but, without a doubt, art was already coursing through his veins. In Mallorca, "his island", where he became enamoured with the caves and the sea, he met Joan Miró who would have a profound influence on his early work (animal themes, which became a constant throughout his career, and a markedly Expressionist style). In his teens, he studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in the island’s capital - Palma de Mallorca - participating, aged 16, in his first collective exhibition – “Art Jovenívol” - and then organizing his first solo exhibition at the Picarol Art Gallery at 17. In the 1970s, Barceló travelled to Paris where he discovered the work of Klee and Dubuffet and also encountered Art Brut, a school with which he felt an intimate connection and which became a new starting point from which to explore new horizons.

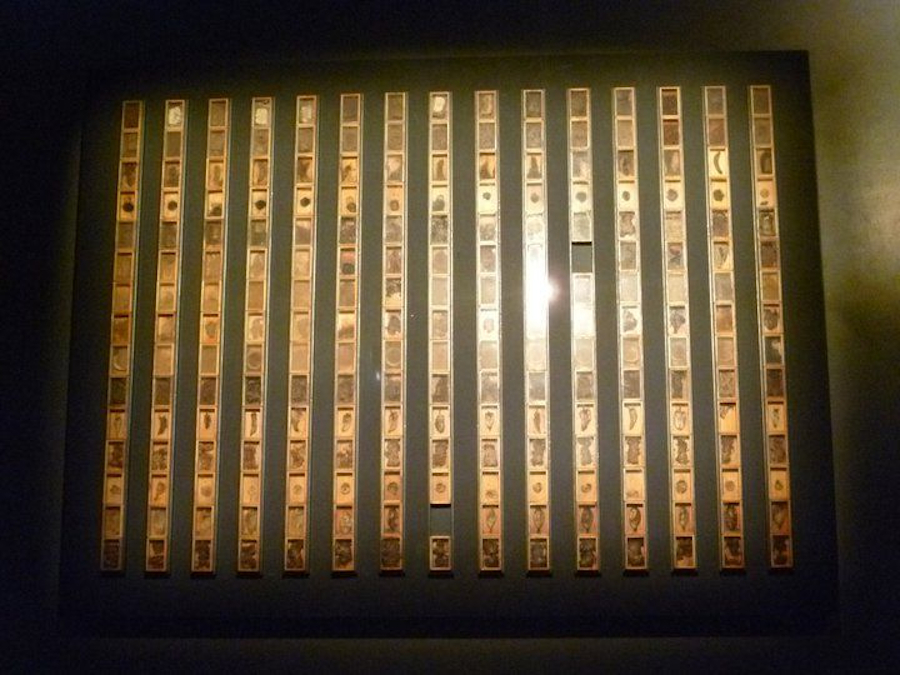

"Cadaverine 15" (1976)

Names such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning and Lucio Fontana then joined the list of his early influences, along with, of course, masters such as Velázquez, Tintoretto and Rembrandt who kept his work well rooted in excellence and classicism. During those years, he continued to demonstrate his concerns for both art and the environment, combining the organization of various exhibitions with activist action such as occupying the uninhabited Sa Dragonera island in 1977, with the aim of preventing its urbanisation. It is then that he meets and befriends the artist Javier Mariscal. From his very earliest years as an artist, Barceló made clear his deep affinity with Nature - always experimenting and incorporating natural and organic material into his works, with some of them embarking on their own journey of evolution over the passage of time. He would leave his paintings outdoors at the mercy of the elements which caused them to crack or rust. He also used organic matter, the deterioration of which was very much a part of its artistic significance, as seen in his exhibition “Cadaverine 15” (Mallorca, 1976) in which 225 glass-topped boxes containing organic and inorganic material showcased the process of decomposition and decay.

Success in Paris and the beginning of a nomadic life

"Seated Venus Bruta" (1982)

Despite his deep-seated roots in Mallorca, Barceló's restless and curious spirit gave him itchy feet and he left the island in search of new locations for his art. In 1980, he landed in Barcelona and set up a studio there. That year, his career enjoyed a boost that would prove key to his future artistic career: he was the only Spanish artist selected to participate in the prestigious Kassel Documenta (Germany), in its seventh edition. He was still only 23 years old but showed a talent, a work ethic and a maturity that set him amongst the most important international creatives of the time. In fact, just two years later, he achieved the distinction of exhibiting in Paris, the art capital of the world, at the Yvon Lambert gallery. Success, however, did not mean that the young artist would rest on his laurels or settle down; in the ensuing years, Barceló would often move house and participate in various projects located in other European cities. This need to venture into other countries and experience other realities would almost become a lifestyle for the artist and would have a powerful influence on his work.

"Wet Novel" (1985)

Throughout his travels and multiple art projects, Barceló comes into contact with some of the most important figures in the art world of the time. Among them is the Swiss gallery owner Bruno Bischofberger, who was to have a decisive influence on his career and become his art dealer at international level. He also meets his future wife - the Frenchwoman, Cécile Franken. The year 1986 would see his fame cross the Atlantic to New York where he exhibits at the Leo Castelli gallery. He falls in love with the city and sets up a temporary studio there, in which he will work and live for several months. These are years of recognition for Barceló, an artist who had always been a legend in his homeland, and he receives the National Prize for Plastic Art in the painting category. Soon, the call of the homeland and the Mediterranean begin to become irresistible and he returns to Mallorca.

Trip to Mali: The beginning of a passion for Africa

"In Mali" (1989)

Not a year goes by without Barceló’s restless spirit demanding new changes. In 1987, he travels to Paris and settles there, making the city his home from time to time, as it remains to this day. The following year will be a turning point in Barceló's life and work. He travels to Africa with a group of other artists but, instead of returning with them to Spain, he decides to stay on in Mali and also to travel around Senegal and Burkina-Fasso. These experiences are described in his "African Notebooks", written in both French and Catalan, which reveal the writer coexisting alongside the painter.

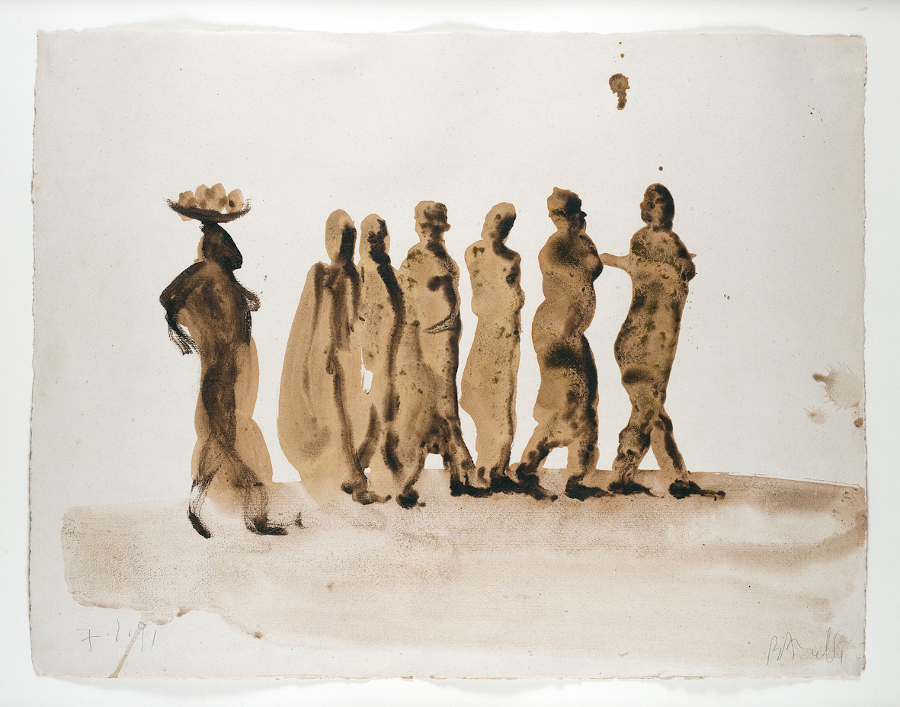

"Mali". Gouache on paper (1991)

Barceló then develops an intense love and deep connection with these peoples and places, as evidenced by the magnificent drawings that date from his time there. Contact with local people and life in the desert define his subject matter and methodology. He begins to show his concern for the natural environment, the passage of time and the origins in everyday scenes and small African landscapes, more detailed drawings, dense, dark raised surfaces that give the impression of reliefs, and for which he takes advantage of the mud and natural pigments he has at his fingertips. These works are now part of different public and private collections around the world, and have been displayed in several exhibitions, such as the one organized in 2008 by the Centre of Contemporary Art in Malaga. But Barceló does not limit himself to Africa and it is at this time that he adds a Mali workshop studio as a final corner to complete his vital triangle, along with Paris and Mallorca.

Awards and architectural projects

Chapel of Sant Pere in the Cathedral of Palma de Mallorca

1986 saw the beginning of his involvement with architectural projects, painting the dome of the lobby of the Mercat de las Flors Theatre in Barcelona. At that same time, 'velatura' starts to appear in his painting, along with overlays of materials giving the impression of transparency. Barceló continued to work without interruption and in 1995 he was selected to participate in the Venice Biennale and, three years later, the first major retrospective exhibition of his work was on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona. The awards kept coming over the decades until, in 2003, he was awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize for the Arts. The following year, the artist undertakes one of his most important projects to date - decoration of the Chapel of Sant Pere inside the Cathedral of Palma de Mallorca, which was completed in 2007. While the spectacular space underwent a renovation to its liturgical elements of stonework, stained glass windows and furnishings, Barceló also added a 300 m² ceramic mural representing "The Feeding of the Five Thousand". The work features a series of constants in Barceló's work - the sea, flora and fauna, grottoes and caves.

Dome of Room XX or the Human Rights and Allliance of Civilisations Chamber, UN European Headquarters, Geneva

The Dome of Room XX or the Human Rights and Alliance of Civilizations Chamber at the UN’s European headquarters in Geneva is one of his works with the greatest international import, albeit not without controversy due to its use of funds otherwise destined for Spain’s development aid budget. It is a huge 1,400 m² dome from which hang thirty-five tons of paint in the form of coloured stalactites, made with pigments sourced from all over the world. On the technique, Barceló commented: "I wanted to take painting against the laws of gravity to the extreme." and went on to explain: "On a day of intense heat in the middle of the Sahel Desert, I vividly remember seeing the mirage of an image of the world dripping skyward […] The cave is a metaphor for the agora, the first meeting place of human beings, the great African tree to sit under and talk about the only future possible, one with dialogue and human rights."

Work that branches out and grows on different terrains

"Large Cove" (2018)

Barceló continues to expand his broad body of work at his three studios in Mallorca, Mali and Paris. His incessant and restless activity seeks an outlet in all kinds of media: illustrated books such as the poet Enric Juncosa’s "Book of the Ocean"; the forwards and texts of his own catalogues and notebooks; photography books such as "The Cathedral Under the Sea"; a book for the blind, "The Dismantled Shops or The Unknown World of Perceptions", with text in braille; and the three volumes of Dante's "The Divine Comedy" which were subsequently the subject of an exhibition at the Louvre in Paris.

Performance at the inauguration of the "Noah's Arc" exhibition (2017)

With his penchant for experimenting in every field of the arts, Barceló has also designed sets for opera. In Falla’s "Master Peter's Puppet Show" at the National Theatre of Comic Opera in Paris, he created the staging, costumes and large-scale puppets; and for Mozart’s “The Abduction from the Seraglio” at the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence in 2003, he took on the entire set decoration. More recently, Barceló has demonstrated his versatility and artistic passion via large exhibitions and personal interventions, such as his "Performance" in 2017 at the inauguration of "Noah’s Arc" at Salamanca University. Miguel Barceló interviewed by Elena Cué

Interview with Miquel Barceló. By Elena Cué

Exhibitions

Miquel Barceló. Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2009

In 2009, Barceló represented Spain again at the Venice Biennale in its 53rd edition. The exhibition showcased a series of large format canvasses from the previous nine years and also included ceramic pieces along with more recent work carried out during his decoration of the United Nations dome in Geneva.

“Miquel Barceló. 1983-2009” (2010)

“My life is like the surface of my paintings." This quotation from Barceló kickstarted an exhibition organized by the La Caixa Foundation and held at its headquarters in both Madrid and Barcelona. The show comprised a selection of 180 pieces completed between 1993 and 2010 and included some of his largest paintings alongside his sculpture "Big Elephant, Upright".

"Sol y Sombra (Sun and Shade)" (2016)

This exhibition opened in 2016 in one of Paris’s most iconic buildings - The National Library of France - which partnered with the city’s Picasso Museum to host a joint exhibition. Visitors were treated at both venues to the display of some never-before-seen pieces, enabling them to experience an authentic immersion in the Majorcan artist’s universe.

“Noah's Arc” (2017)

Salamanca University’s eighth centenary celebrations included a large exhibition of Barceló's work. The artist himself participated, performing during its inauguration. The exhibition took up four spaces at the university, as well as the city’s main square, with works from multiple disciplines: sculpture, ceramics, drawing and the performance itself.

"Miquel Barceló. Metamorphosis" (2021)

2021 began in Malaga with an exhibition held at the Picasso Museum, which included around one hundred works created by Barceló between 2015 and 2020. The exhibition took its name from Kafka's famous novel and comprised a selection of pieces on canvas and paper, as well as ceramics, notebooks and bronzes.

Books

Notebooks from Africa. (Galaxia Gutenberg Círculo de Lectores, 2008)

Barceló's journals from his stays in Africa between 1988 and 2000 have become an important body of work within his career. The entries compiled in this publication are interlaced with drawings, watercolours and gouaches from Mali, Senegal and Burkina-Fasso. The text, originally in French and Catalan and complemented by sixteen pictures, includes shopping lists, letters to friends, his fears and desires, details about the process of artistic creation, ... The writing is vivid, absorbing and the perfect accompaniment to the artistic output that immortalized Barceló's ‘Africa’ years.

Aurea Dicta. (La Casa dels Clàssics, 2018)

An authentic work of art, multi-award-winning and marked out for posterity. The Aurea Dicta project began in 1992 when a group of Catalan intellectuals set out to, in their own words, "for the first time, translate the Greek and Latin classics into modern-day Catalan in rigorous, entertaining and bilingual editions, in order to democratize and elevate the Catalan language and culture". The book is illustrated by Barceló in such a way that art dialogues directly with classical thought.

Un Grand Verre de Terre (A Large Glass Of Earth). (La Fábrica, 2020)

Once again, an artist's notebook that fuses Barceló's plastic artwork with an account of his lived experience and boasts beautiful photographs of the window panels he designed for the National Library of France in 2016. The images are especially important as this was a work of ephemeral art - the clay-on-glass fresco was dismantled by the artist himself at the close of the predetermined exhibition time. The notebook describes the process, sensations and end result of the work from the point of view of its creator. As the publisher points out, "a living work, designed to be observed from inside and outside the building, which introduced the visitor to an extraordinary exhibition".

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Miquel Barceló: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

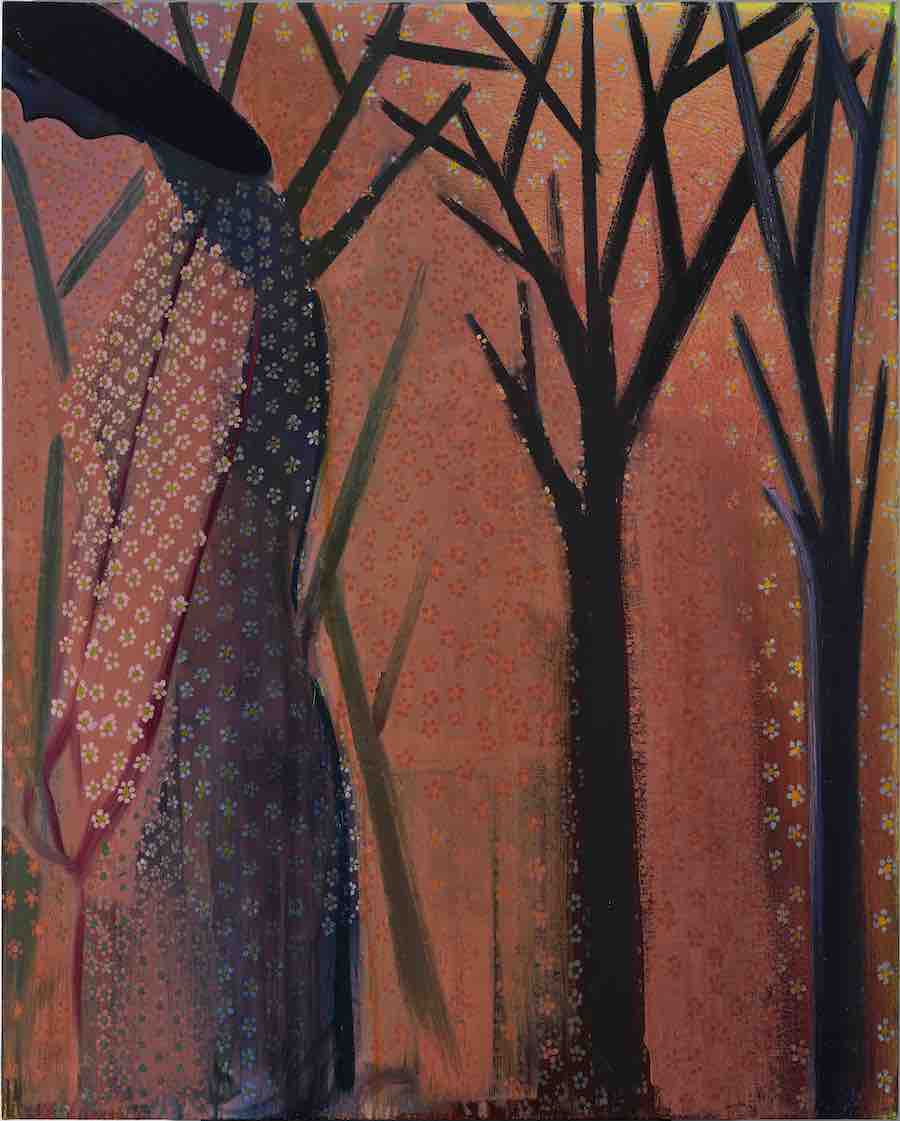

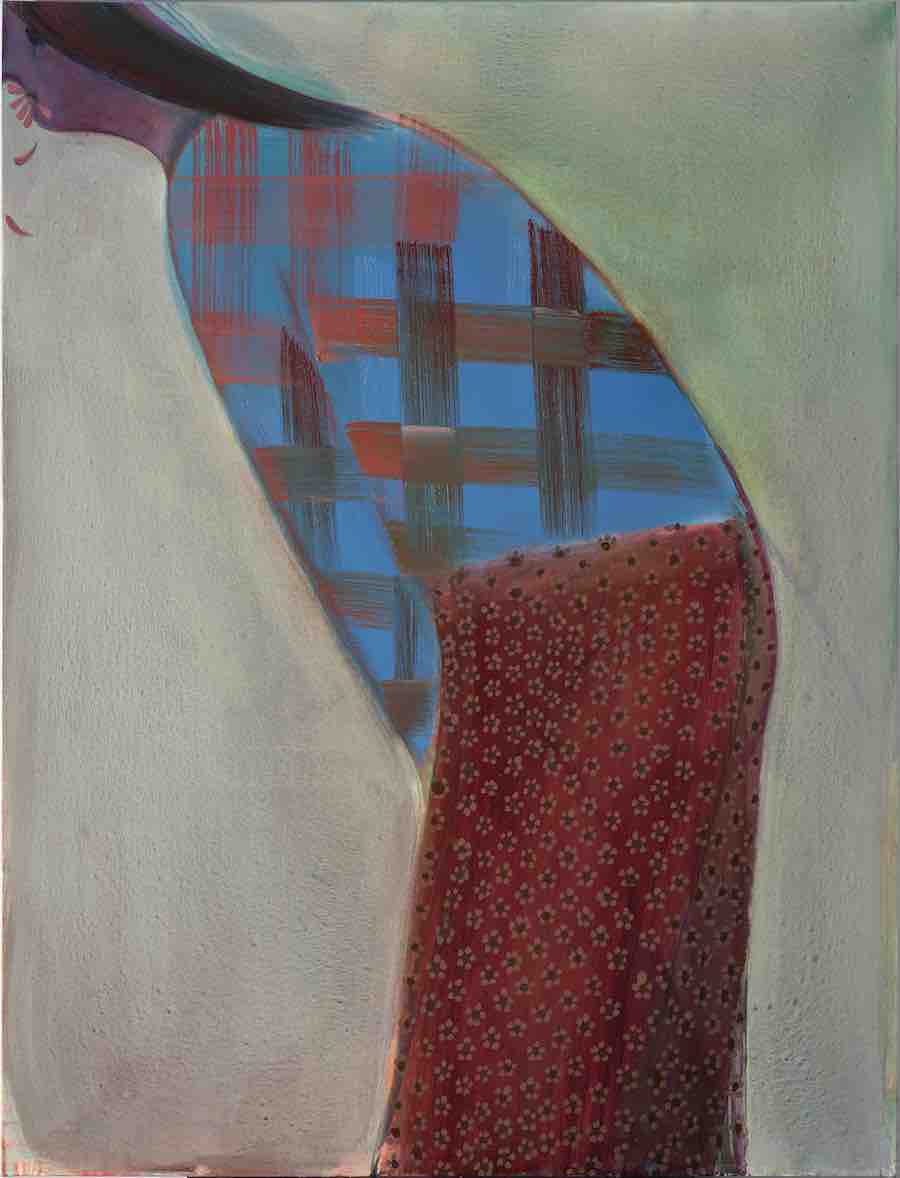

The Fahrenheit Gallery, Valeria Aresti's beautiful Madrid art space, is currently hosting the exhibition “Some Other Sunset” by rising New York star, the painter Heidi Hahn (b. Los Angeles, 1982). It comprises a series of 7 medium-sized oil paintings and 8 drawings, each of them dominated by the silhouette of a female body. These are women lost in thought, silent and, for the most part, in a forest lit only by the sunset.

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 4, 2021 oil on canvas

The Fahrenheit Gallery, Valeria Aresti's beautiful Madrid art space, is currently hosting the exhibition “Some Other Sunset” by rising New York star, the painter Heidi Hahn (b. Los Angeles, 1982). It comprises a series of 7 medium-sized oil paintings and 8 drawings, each of them dominated by the silhouette of a female body. These are women lost in thought, silent and, for the most part, in a forest lit only by the sunset. Their faces are schematic, some have neither mouth nor eyes, but even so, they seem given over to deep, prolonged thoughts and lost in a loneliness that is palpable in each of the brushstrokes that compose the sleeve of her sweater or the rays of golden sunset on her shoulder. Through them, Heidi Hahn seems to want to sign a declaration of principles that distance her subjects from the classical canon and its interpretation, widely-held until the beginning of the 20th century, namely, the naked bodies of women as the focal point of their beauty. Instead, she wraps them - or rather shields them, like a cuirass - in clothing that is loose-fitting, neutral, warm and nondescript. Their faces, barely hinted at, also alert the visitor to the fact that, in this exhibition, physiognomy takes a backseat to the volume of the body. There is also a lot of silence, stillness and an incessant question floated on the air: What are these women thinking about?

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 5, 2021 oil on canvas

From the outset, the contour lines of these bodies seem vaguely but surely reminiscent of Matisse and also, due to their solidity, of Picasso from his classical period. Matisse and Picasso, two undisputed trailblazers who, by the same token, arguably set both the standards and the constraints preventing young artists from being free to step outside the confines of some very marked, very recognizable patterns. Playing supporting roles in this exhibition are the simplified outlines of trees, hazy, barely there, and, in most of the works, the coral pink lighting of a sunset. It is, perhaps, this twilight colour that lends a somewhat sad, prolonged tone and very intimate voice to these women suspended in time. On these bright spring days in Madrid, the autumn light in Hahn’s paintings, the red sunsets, the leafless trees with black trunks, seem somewhat far removed from us. And yet, there is something deeply familiar to us in the message communicated from those lonely, pensive figures. And so it is that these women, lacking in form and expression, beguile us precisely because they confront us with something that is strangely close, something that is palpable in every square metre of Madrid’s pavements: loneliness, introspection, doubt. Hahn's women return us to the most fundamental questions, the ones that fill our lives and cities today during what will hopefully be the last days of the pandemic. Who are we, where are we going, what is going to happen now?

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 2, 2021 oil on canvas. Never Mind a Sunset 4, 2021 oil on canvas

Hahn's peculiar way of dressing her subjects is very much in keeping with her idea of altering the function of clothing so as to turn it into something that shifts between a layer of protection and an architectural covering: "I have painted women for a long time now just because I feel like I don't know if I represented them yet in a way I find truly convincing [...] I keep chasing this idea of like 'oh I like the iconic idea of women, but I don't like the classical.' I don't like romanticism that's through the lense of the male gaze; the cliché male gaze. I care about how I see these women and how I want to represent the women in my life [...] These women are trying to become something that they don't necessarily have access to yet. And, so maybe the paint tries to point them in the right direction, if that makes sense, it's trying to give them that strength where there is still that vulnerability, there is still something that is not quite figured out and that's why the figures are looser, and their faces have this idea of falling apart while trying to become something that is very solid." says Hahn. The attention to detail that Hahn pays to the fundamentals of technique is powerful - line, light and colour are the three keystones of an archway – her archway - leading us through areas of flat colour and transforming them into places of feeling and emotion. Brushstrokes ranging from the almost liquid and transparent to the thickest, loaded with pictorial mass. Here, in a large number of canvases, she uses a striking technique, namely - painting simple flowers in repeated patterns as if they were on printed fabric or wallpaper. Up close, the texture of these fake block prints makes them almost touchable which leads us to believe that Hahn transforms feelings into something palpable.

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 6, 2021 oil on canvas

These paintings are a tribute to ‘woman’ and her inner life. The way the paint is applied in different layers intensifies the narrative of each painting, calling to mind Edvard Munch and his search for the psychological portrait. Hahn strives to capture emotions and pent-up feelings. She turns the average woman, the one going about her daily routines, into her icon. Her anonymous characters seem lost in their own worlds and thoughts as they shop, sweep, prepare food, or tap on their mobile phones. They are, therefore, in total contrast with the widely-held consensus on ‘woman’ today – that she is more preoccupied with her appearance, fashion fads, the gym and the rat race. Hahn, however, avoids all emphasis on the physical aspects of her models, or even their femaleness, to accentuate instead their moods. This is why Hahn speaks of a "narrative formalism", referring to the amalgamation of paint and figures that happens in her work.

Heidi Hahn. Never Mind a Sunset 1, 2021 oil on canvas

Hahn likes to work in series of sometimes up to 14 canvases at a time. She groups them together in her studio and works on them, moving them around, looking for connections between each of them and creating a simultaneously different and unique voice at the same time. Layer by layer, broad washes of colour emerge which will become the bodies and, later, their voices. Rather than beginning a painting from a sketch, she invariably develops her compositions during a pictorial process that has already begun its journey. This method of “abstract metamorphosis” aims to lead the viewer's eye beyond the pictorial surface: "So, I always think of myself not as a straight figurative painter, but like a narrative formalist. Which means I need the paint, the materiality of the paint, to work as hard as the image is going to work. They need to go hand in hand, the content and materiality need to go hand in hand to create the painting and what it is trying to be. And so, the paint itself is trying to tell a story with how it's painted: the texture, the brushstroke, the gesture of the paint moving within a certain shape. And so, to me that is even more important than creating the image. And, if it's just image based I am not really interested in that. I am more interested in the paint doing the heavy lifting rather than the thing it's trying to be," she explains.

Born in Los Angeles and with a Ph.D. in Fine Arts from Yale, Hahn, now living in New York where she is Assistant Professor of Painting at Alfred University’s School of Art and Design, explains: "So, If I paint a face, it's more like: how is this texture being defined with the medium? How is it being defined with the mark making? How do the colours interact with each other to create that tension? And, I also think of residue in the painting, where everything is trying to be something that is a residue of a reality [How can paint mimic reality?] It's just paint. And the way the paint works to create this artifice, I am really interested in. And, I am really interested in these artificial components trying to make up a reality." Hahn never works from a preliminary drawing; she lets everything just happen and evolve after the first brushstroke, born of uncertainty, after which each character follows its own course and the oil paint guides the form: "In these works, the woman becomes a tool of visual seduction, the formal aspect of the paint delaying ownership over the content [...] I don’t know what exactly these women want to hide themselves away from, but I feel that it is necessary in order to really be seen, be themselves. Defined by the artifice of paint, they are untouchable, camouflaged by beauty and anonymous in profile. The works on paper also offer a respite from definition, the seriality leading to anonymity," says the painter. Hahn fell ill with COVID in April last year, at which time she felt the virus made her aware of being "just a body" up against the world. She admits to feeling scared and thinking that her body did not belong to her. She also thinks that, as a result, she found it more difficult to face her work: "I find it hard to put aside a pandemic and political unrest and carry on creating something that resides in an intellectual framework and trades in a formalism devoid of the present reality”. She adds: "I think the future of the art world will become insular. If you are a maker, you have the compulsion to make, regardless of if you are able to show it to the world".

Thus, the women who emerge from Hahn’s paintings no longer belong to the concrete world of people, having entered that other plane populated by figures made of texture, line, gesture and colour and in the form of moods.

Heidi Hahn

Some Other Sunset

Galería Fahrenheit

Justiniano, 8

Madrid 28004

19 de mayo 2021- 15 de julio 2021

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- Los atardeceres de Heidi Hahn en Madrid - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

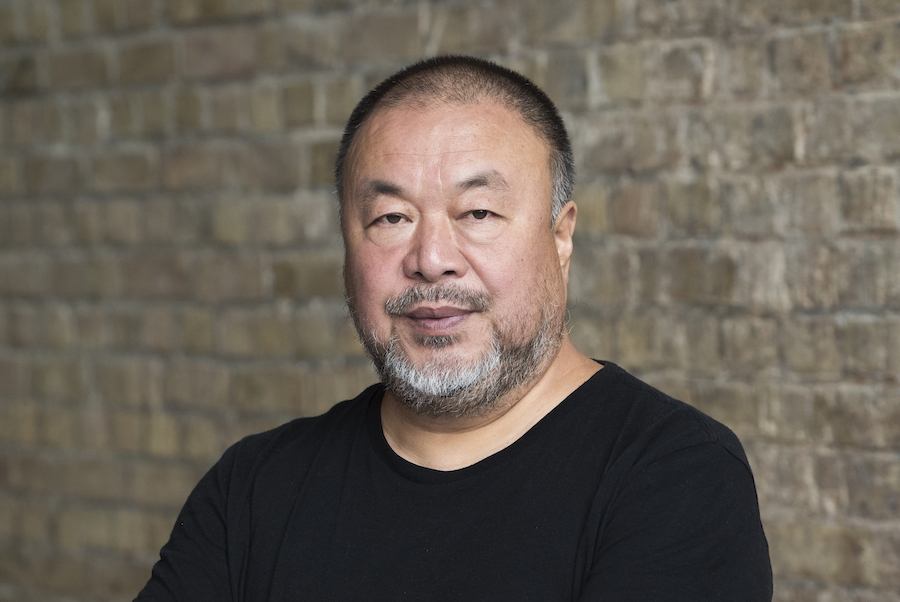

Recently inaugurated in Lisbon, Rapture, is the largest exhibition by artist and political activist, Ai Weiwei, (Beijing, China, 1957) described by The New York Times as one of the most important critical artists of our time, with his eloquent and unsilenceable voice for freedom. The exhibition title has various meanings; one is the “transcendent moment that connects the earthly dimension with the spiritual dimension.” Another is the “hijacking of our rights and freedom”

Ai Weiwei © Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

Recently inaugurated in Lisbon, Rapture, is the largest exhibition by artist and political activist, Ai Weiwei, (Beijing, China, 1957) described by The New York Times as one of the most important critical artists of our time, with his eloquent and unsilenceable voice for freedom. The exhibition title has various meanings; one is the “transcendent moment that connects the earthly dimension with the spiritual dimension.” Another is the “hijacking of our rights and freedom” and this significance may well encompass the definition of the artist’s own life. A life which began with the vital experience of anguish and rupture when his father, the poet Ai Qing, is sent to a labor camp with his family and subsequently exiled during the Cultural Revolution by the anti-right movement, instigated by Mao Zedong. A lot of the inspiration for his artistic creativity stems from examples of lives torn apart, like those confined to refugee camps, lives ripped of freedom, lives destroyed as in the human flow of emigration, cries from corruption and totalitarianism or of sorrow by the ease with which human rights are violated.

Could you tell me about your exhibition Rapture?

It is an exhibition that includes works dating from the 1980s to yesterday, just before the exhibition opened. It contains eighty of my works, many of them are major works. It is the biggest exhibition ever organized, approximately four thousand meters squared in total and includes old and new works, installations, films, photographs and videos. It is a collection of all kinds of different works.

Which of the pieces from your exhibition has the most relevant meaning to you?

Every single work has a certain meaning and no one piece could take the place of the most relevant for me. I could not select one specifically because they are all from different periods. To me, they are all important.

After all, your work is a narration of your life, it is your biography.

Yes, it is like a biography. It would really take a considerable amount of time to contemplate all the works due the numerous videos and movies. They do indeed tell my story.

Rapture. Ai Weiwei © Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

The most recent works in this exhibition are a reflection of your Chinese roots. What values did you learn from your father, the famous poet Ai Qing?

My father’s life was very dramatic. He was a poet who had a strong influence on Chinese revolutionaries. After the nation was established, he was criticized as a rightist and was exiled for 20 years. During all those years, he was forbidden to write. I think my father is important, he was always very open and positive in a very innocent way, which made him very strong, to the extent that even the political storm could not really change him into another person, he remained true to himself.

You use art as an instrument of social and political awareness. What do you think about artistic creations without a purpose?

I believe that to think of art as not related to reality, humanity and even human struggle is simply not art. At least, it is not the kind of art I would appreciate or even understand. Otherwise, why do we need art? Nature is much more impressive. If you look at anything from nature, from a leaf to water, you would notice it is much more complex and much more beautiful than anything an artist can create. Artists must create emotions and an understanding of who we are and what kind of society we are living in. Just like literature and poetry, there is always some kind of hidden intention. It is not just a string of empty words and vocabulary, that is impossible. Art has always been misunderstood as a decorative tool, as if it is trying to decorate some type of life, but that is nothing more than a misunderstanding of the function of art.

You use art as a platform to voice and help the less fortunate defend their human rights and freedom of expression, but what does art do for you?

What I receive from my practice is life. Life itself is a practice. Without practice, there is no life. It becomes me and I become what I am trying to be as a piece of art. I need to find a language to define my life. If I do not find that language, it is simply as if I never existed or I never had a life.

Rapture also presents your last documentary Coronation where you talk about China’s "ruthless efficiency" in the face of the pandemic. If compared to the leadership of other countries such as Brazil or India, it seems like this merciless management has prevented many deaths, suffering, economic dramas ...

If you look at the numbers, yes, China is very successful. At the beginning, they said there were only 3000 deaths, now there are 4000 but the numbers were never true. Yes, they controlled the disease but at the same time, they controlled people’s spirit, people’s understanding about life itself. People have the right to be free. The state should not have that kind of power, a military type of power to supposedly ‘take care of people’ but at the same time really unhinge them. There is no humanity in that. You cannot treat people like animals. The state has become over powerful but yes, I should say that it has successfully controlled the disease.

China deprived its people of their freedom but protected its nation during the pandemic. What do you prefer: freedom or protection?

Freedom is not an empty word. Freedom includes our individual consciousness and our way to protect ourselves, others, and society. The individual must defend their rights. The government has no right to tell people what to do. It can make suggestions and organize resources, but it is in no position to force people to do anything.

What do you think about the European Union’s support of Biden's request for a new investigation into the origin of Covid in an attempt to ensure it never happens again, as stated by the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen?

Firstly, you can never really find out what happens in China. It does not matter if you carry out an investigation or not. China, as a society, has a certain characteristic that will ensure many things will remain a secret and nobody would be able to find out. Not only in this instance but also in every other political disaster, they never reveal anything truthful. Of course, today, I think we should understand the nature of the disease to prevent it happening again and avoid it happening every year. This is the biggest disaster and China, as a responsible large nation, has the duty to tell the world what really happened at the beginning of this disaster. However, I am convinced they will not let anyone know.

You have been very active in raising awareness about the problems caused by climate change. What do you think of the recent commitment made by China and the United States to reinforce the Treaty of Paris and collaborate in the reduction of greenhouse gases?

I like it. It is a positive step in the right direction. If China really commits to it, it has the potential to be very efficient. This is something every politician talks about, however, it is very hard to measure what is actually being done. Each nation is at a different stage of development and therefore they have very diverse ideas on how to limit this kind of behavior or how to take action. Nevertheless, it is good they have started to talk about these issues.

Which image from the past year has impacted you most? Crematories on the streets of India, cemeteries in South America…

There are so many, too many in fact, so again it is very hard to select just one. There were simply too many shocking images.

The refugee crisis and the “human flow” of migrations are central themes in your work that you particularly want to accentuate. The dignity of the human condition is at the heart of your concerns. In effect, you grew up as a refugee yourself because of your father's situation. What positive aspects have you drawn from such a traumatic experience?

As you said, I grew up in China, in a way, as a political refugee myself, so I am always wondering how Europe is dealing with the situation. Now I realize Europe is trying to look the other way and ignore the refugee crisis. Personally, I am extremely disappointed by this behavior. Thousands of refugees are being pushed away and have lost their life in the ocean. That is a fact. A lot of children, women and elderly people are just being pushed away. They cannot even reach the border. And even if they do reach the border, they (the authorities) will not let them through. This is an unthinkable situation. I could never have imagined that Europe would be capable of that, but they really have done it and in plain sight for everyone to see. It has changed my perspective on our human condition.

What is your opinion on the agreement reached between the United States and Spain in favor of “migration carried out through regular channels and in a safe, orderly and humane manner" as stated by the Secretary of State Antony Blinken?

I think if state policy is only choosing to talk about the humanitarian crisis as a tactic, it is a hypocrite. The US is still involved in wars, selling weapons to many nations which should not even be considered as democratic societies. I believe the US is responsible, and should be held responsible, for many other humanitarian crises happening around the world: what happened in Afghanistan, the US relations with Saudi Arabia, and many others that are very questionable. Therefore, when they talk about providing humanitarian help, first, they should stop producing war machines and stop interfering in many regional problems, not to mention the many other problems they create.

Meanwhile, you have opened another exhibition Marbre, Porcelaine, Lego in the Max Hetzler Gallery in Paris. What vengeful work can we find here?

The show follows my activities from recent years. My porcelain and Lego works portray motifs related to the migration and refugee crisis, which could also be called a humanitarian crisis. The idea is to combine the well-developed tradition of blue and white porcelain in China with the modern practice of the material Lego to create a unique expandable strength.

Ai Weiwei, After the Death of Marat, 219. LEGO bricks 231 x 269.5 cm

- Interview with Ai Weiwei - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

Francisco de Goya's work is universally famous for its spectacular quality, its modernity and its commitment. The Fuendetodos teacher was a pioneer in technique and subject matter; a nonconformist in a society where he never quite fit in, but who surrendered to his dazzling artistry.

"Time also paints"

“The painter Francisco de Goya” (1826). Oil on canvas. Vicente López Portaña. Prado Museum

The Prado Museum is among the world's greatest art galleries and of all its rooms, the ones that draw visitors like a magnet are those showcasing the works of Francisco de Goya ~ one of the most important, charismatic and iconoclastic painters ever in the history of painting. His "Black Paintings" and engravings suite are much admired for their astonishing modernity and break from the norms of their time; his Costumbrista, portrait and religious paintings dazzle with the light they emit and the contemporaneity of their brushstroke which transforms them into works that are almost pre-Impressionist. His concept of art transcended that of the mere reflection of what surrounded him, instead interpreting his work as something in constant evolution: "Time also paints," he said on more than one occasion.

Goya's case is almost unique in the history of art, comparable only to that of masters such as El Greco or Turner. It is the story of those artists who shunned the schools of their time to pursue an art that would not be understood until many decades later, the intentions of their art being different, very different from those of their contemporaries. In Goya's own words: "The exceptional qualities of their work are ruined by these mannered masters, who always see lines and never bodies. But where do they find lines in nature? All I can see are light bodies and dark bodies, planes that move backwards or forwards, reliefs and concaves." - words that many avant-garde artists of the 20th century could subscribe to, written more than 150 years earlier.

Early learning and a trip to Italy

Francisco de Goya was born in Zaragoza on 10 March 1746 with art running through his veins, the son of a master gilder and a mother from the lower rungs of the aristocracy. In the mid-18th century, Zaragoza was a rich and powerful city with a flourishing business in the construction of churches and convents which then needed craftsmen to decorate them with altarpieces, paintings and panels. Goya's father's skills were much sought-after and he decided to push his children's aspirations along the same path. The future Court painter took his first steps towards paper and canvas aged 13 under the tutelage of José Luzán Martínez, who had been schooled by Neapolitan painters and whose influence would prove decisive in Goya's attraction to Italian painting. After Luzán Martínez, Goya continued his apprenticeship with Francisco Bayeu and, at the age of 17, applied for a grant and tenure from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando but was turned down. A further application in 1766 was again unsuccessful.

"The Esquilache Riots" (circa 1766)

Works attributed to Goya at this time are scarce, with some religious-themed paintings remaining but the one that stands out most is "The Esquilache Riots" (c. 1766). It is an ensemble painting that depicts an actual incident of great intensity and social relevance and displays some of what will become future constants in his work: the theatrical use of light and shadows, loose brushstrokes, vibrant colours, movement and a marked interest in balance and composition. In 1770, the young artist travelled to Italy, where his passion for masks, popular customs and street theatre was born - a passion that tallies with his fascination with people's faces and grotesque figures. During the trip, Goya decided to submit his entry in a competition held by the Academy of Fine Arts of Parma: "Hannibal the Conqueror views Italy for the first time from the Alps". While Goya's eponymously-titled painting garnered good reviews, the potency and "lack of realism" of the colours did not convince the jury to award him first prize. Goya's risky, personal and vibrant artistic style was already standing out for its modernity against the obvious academicism of his colleagues.

"Hannibal the Conqueror views Italy for the first time from the Alps" (1770). Selgas-Fagalde Foundation

First steps to success. Frescoes and Tapestry Cartoons

Detail from the Chapel of the Conde de Sobradiel, Zaragoza (1770). Barboza Grasa Archive

On his return, a now 25 year-old Goya takes on his first important commission: to paint a fresco in one of the vaults of Zaragoza's Basilica of the Pillar, applying the techniques learnt during his stay in Italy. This work wins him more contracts: frescoes for churches and palaces and, primarily, portraits of the Aragonese aristocracy. It was during this time that he completed paintings to decorate the chapel of the Palace of the Count of Sobradiel. His work earns him a certain fame and a stable position, factors that convince his former teacher, Francisco Bayeu, to allow Goya to marry his sister Josefa. Of all the seven children from their marriage, only the youngest, Francisco Javier Pedro, will survive to adulthood. How deeply the deaths of his children tormented the artist's soul will emerge later in his "Black Paintings", "Caprichos" and "Disparates" print series.

"The Pottery Vendor” (1779). Tapestry cartoon for The Royal Factory of Santa Barbara

1775 was to be a crucial and life-changing turning point for Goya. Anton Raphael Mengs, first painter to King Charles III and also commissioned as master painter by other European courts, calls on him to design and paint tapestry cartoons for the Royal Factory of Santa Barbara. The first ones were painted that same year: a total of nine works, each serving as a pattern guide for tapestries destined for The Royal Seat of San Lorenzo of El Escorial. Goya continues his production and the following year begins another series of cartoons, this time destined for the collection of the Palace del Pardo. Between 1778 and 1780, he both worked and lived at court which afforded him the opportunity to befriend the then Secretary of State, the Count of Floridablanca. This and other relationships, together with his undeniable talent and the originality of his work, guarantee him stability and Goya will then take his first steps towards becoming the future Court Painter. In 1780, he presents "Christ on the Cross" in support of his application to enter the Royal Academy of San Fernando and is admitted unanimously

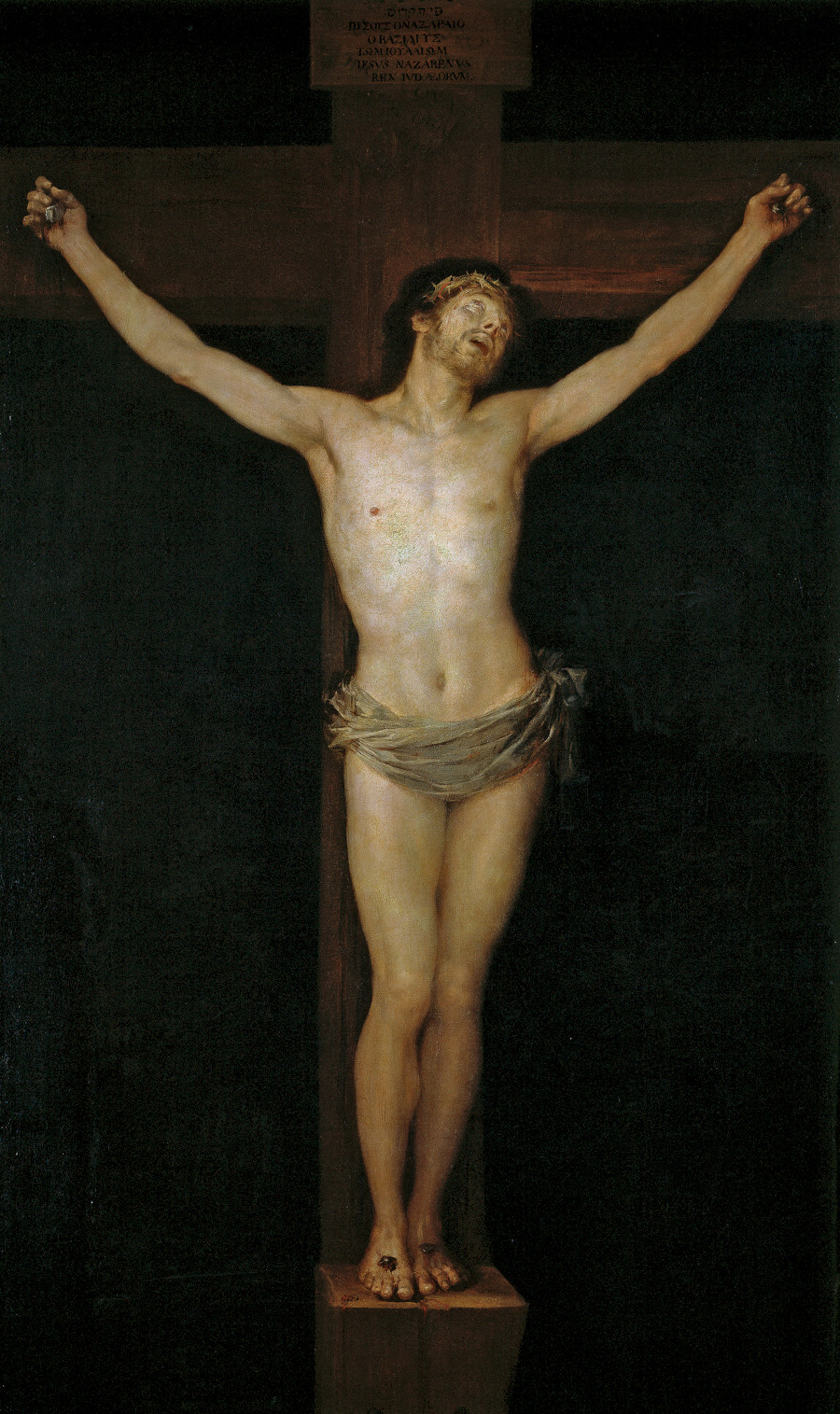

"Christ on the Cross” (1780). Prado Museum

A career on the rise: Jovellanos, Ceán Bermúdez and the Enlightenment

In that era, art and painting were characterized by their ironfisted academicism. Neoclassicism cast a long shadow over artists forced into ironclad and stereotypical constraints based on centuries-old rules. Goya rebels against these impositions and chooses his own path, something that will characterize his work and attitude for most of his life. The 1780s bring him both successes and failures; from the rejection of audiences and academics alike to his Virgin Mary frescoes for the Basilica of the Pillar, to the unreserved acclaim for his "Saint Bernardine of Siena preaching to Alfonso V of Aragón" (1873), created for an altar of the Basilica of Saint Francis the Great. With his fame now well-established, Goya devotes time to painting the portraits of important families and members of the upper classes such as the Duke of Osuna and the Earl of Floridablanca. In fact, the patronage of the Dukes of Osuna was to win him numerous commissions.

"Saint Bernardine of Siena preaching to Alfonso V of Aragón” (1781-83). Basilica of Saint Francisco el Grande

Goya's anxious soul propels him towards certain environments, individuals and ideas that would become fundamental throughout his life. At this time, he makes the acquaintance of Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos and the art collector Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez. Through these friendships, his career as a painter continues to rise, thanks to the numerous commissions they secured for him. However, these commissions were by no means the most important benefit he receives from his friends: they open the doors to intellectual and reformist circles advocating for the Enlightenment to come to Spain. It is a discovery that impacts the artist, who immediately identifies with these new views on education and politics. These are critical and revealing moments which also affect his painting; his canvasses begin to abandon idealist and perfectionist concepts in pursuit of expressionism, as represented by the exaggerated and the grotesque. Unknowingly, Goya becomes one of the forerunners of a movement that would soon spring up throughout Europe: Romanticism.

Ill health, nudes and war. The time of realism.

"The Clothed Maja" (1800-1807). Prado Museum

1792 is a dark year in the life of Francisco de Goya. While travelling around Andalusia, he suffers a terrible illness that leaves him profoundly deaf at the age of 46, a deafness that will accompany him until his death and infuse many of his thoughts and paintings with blackness. The painter finds refuge in his art and creates a series of small paintings where the presence of tragedy and crime is strong. However, Goya rises phoenix-like from the ashes and in 1795 becomes Director of Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. He continues as a portraitist to the nobility, even securing the patronage of the recently-widowed Duchess of Alba. The artist continues to develop his interest in the grotesque, popular folk traditions and social criticism through his engravings, as evidenced in the "Caprichos" (1799). At this time, he also paints his famous works "The Clothed Maja" and "The Naked Maja", which would later bring him the wrath of the Inquisition.

“The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid" (1813-14). Prado Museum

On the outbreak of the War of Independence (1808-1814), Goya is obliged to be seen to take the government's side, although his output does remain critical in series such as "Disasters of War". His wife, Josefa, dies in 1812 which is when it is believed he begins a relationship with Leocadia Zorrilla. After the war, he continues to work as Court Painter to the king and nobility, even going so far as to paint the portrait of Ferdinand VII, the "Felon King" and self-declared absolute monarch he neither liked, respected nor accepted. However, despite only showing the regime-critical drawings and prints to his most trusted friends, his prudence was insufficient protection from the Inquisition which, in 1815, brought a tribunal against him for his "The Nude Maja". Undeterred, he continues his production of etchings with two emblematic series: "Tauromaquia (Bullfighting)" and the unfinished "Disparates (Follies)".

“Carnaval Folly”. Etching 14 from the series “Disparates” (1815). Prado Museum

Final years. The Deaf Man's House and death in Bordeaux.

“Saturn Devouring His Son" (1819-23). Prado Museum