- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

On 7th March 1500, Emperor Charles V was baptized at St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, a fortnight after his birth. The verticality of the central nave, with its very subtly pointed arches shooting up into the sky, was draped in gold and silver-threaded Flemish tapestries; the Gothic stained glass windows, with their heavenly entourage, fulfilled the symbolic function of transforming the interior illumination into an other-worldly light distinct from that outside.

|

Colaborating author: Marina Valcárcel

|

|

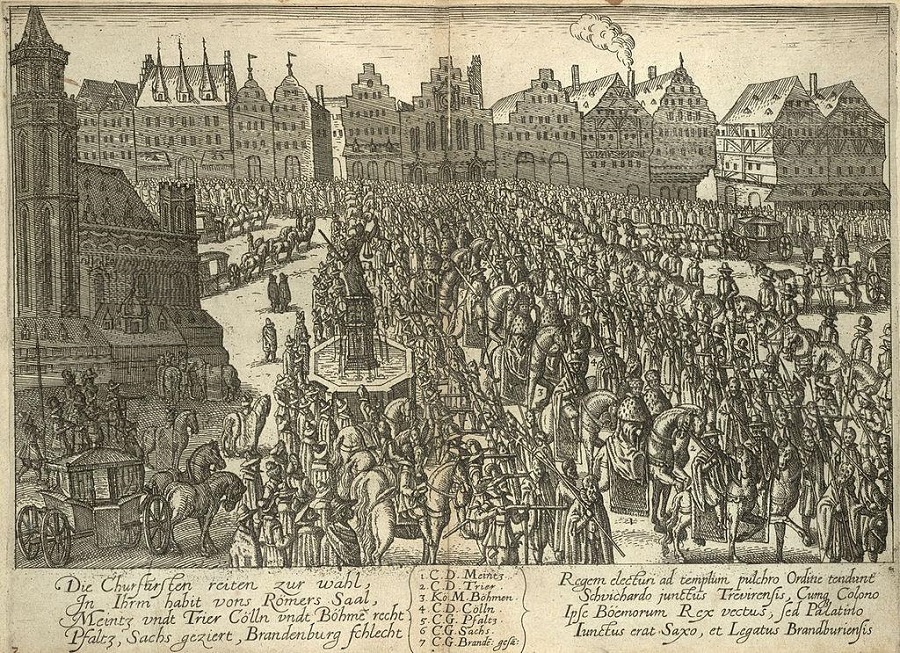

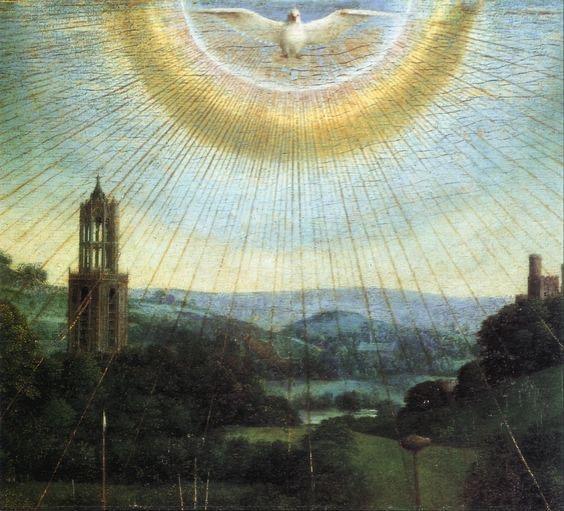

On 7th March 1500, Emperor Charles V was baptized at St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, a fortnight after his birth. The verticality of the central nave, with its very subtly pointed arches shooting up into the sky, was draped in gold and silver-threaded Flemish tapestries; the Gothic stained glass windows, with their heavenly entourage, fulfilled the symbolic function of transforming the interior illumination into an other-worldly light distinct from that outside. A walkway with forty arches was built, each one representing the future states of the newborn and one of the godmothers, Margaret of York seated on a throne, carried the baby, preceded by a lavish royal entourage. This baptism was conducted in the manner of a coronation, leaving behind the simpler medieval ceremonies of the past and instituting this Burgundian ritual in the Spanish crown. But all the pomp and solemnity failed to prevent the eyes of those entering the cathedral being drawn towards the Vijd chapel. There, on 6 May 1432, The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb altarpiece, the Polyptych of Ghent, painted by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, had been inaugurated, offering its awestruck audience a surprisingly new way of viewing art.

Ceremonial cortege, German engraving, 16th century.

In 2012, a team from the Royal Belgian Institute for Artistic Heritage began restoration of the Polyptych in a laboratory at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MKS). During the first phase, when lifting the different layers of varnish, large areas of overpainting were discovered that - probably since the 16th century - had kept van Eyck's work hidden. For the first time, it became possible to see the outer panels of the Polyptych in their original state: the colours of skies and cities, fabric folds and pins hidden in headdresses, light bathing the skin of its subjects and the illusory feel of simulated marble in the statues of the two Saint Johns. These were findings that allowed for us to intuit and piece together many of the mysteries surrounding the paintings of Jan Van Eyck (Maaseik? c. 1390 - Bruges, 1441). This was what sowed the seed of this unrepeatable exhibition displaying all of the eight panels before they return, forever, to the Cathedral of St. Bavo. They form the backbone of the thirteen mysterious, dark rooms of the exhibition, their walls alternately painted the red and ultramarine of the Virgin Mary's robes and their lighting that seems to emanate from inside the paintings: almost 100 works comprising Masaccio, Pisanello and Fra Angelico, his Italian contemporaries, some of his Flemish contemporaries and, above all ,13 of the 20 known Jan van Eyck paintings in the world, constituting a never-before seen collection.

Laboratory at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MKS). Restoration of the Polyptich

The traveler visiting Bruges will see the small enclosed gardens with their espalier fruit trees and the high pointed arrows of the bell towers emerge around the canals and will be seeing the same streets and their houses and the same churches on the other side of a bridge as Van Eyck. Little seems to have changed since 1430. Similarly, when we stand facing a 15th-century Flemish painting, we believe that we are infltrating the intimacy of life of another time.

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail). Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, Cathedral of St Bavon, Ghent.

Silks and Patrons

The birth of Flemish painting was occasioned by the French defeat at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 which spelt the collapse of France for decades. Far removed from the ongoing Anglo-French Hundred Years War, Flanders devotes itself to its vocation of commerce. The 1419 assassination of the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, convinces his son, Philip the Good, to sever ties with the Valois and move the capital of Dijon to that protected and free city of Bruges into which goods from the Mediterranean, the Baltic and all the luxury ships of the East flowed: spices and pearls, Turkish rugs, silk brocades from Syria ... objects that will inundate the spaces between Van Eyck's Virgin Marys, altars and donors. Bruges was already the well-established centre of a thriving school of illuminators, among whom and under the influence of the greatest sculptor of the time, Claus Sluter, Van Eyck begins to paint the folds of robes as voluminous as portico sculptures and saints' faces contorted by expressions of pain and to let his painting take on the preciosity and colors of the jewelled and enamelled cover of a Book Of Hours. The Duke of Burgundy's court was a paradise for fortunes such as those of the Italian banker Tommaso Portinari or that of Chancellor Nicolás Rolin, who favoured the arts and generated much patronage. In this environment, May 1425 saw Jan van Eyck's appointment as court painter to Philip the Good, for whom he undertakes numerous long and secret journeys of which only one destination is known: the Iberian Peninsula.

Limbourg Brothers: "May", calendar page from the "Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry" (1411-1416). Condé Museum, Chantilly, France

Subdjugating the light

So who was Jan van Eyck? What was his optical revolution in response to? What was it that made him paint that way?

One could say that, as a painter, he enslaved subjugated and conquered light, subduing and taming it until he was able to illuminate every corner of his paintings with it. To achieve this, he made use of the well-established tools of antiquity which he mastered and made his own. The most recent scientific analysis, after the restoration of the Polyptych, shows that van Eyck mastered all oil techniques and took them to their limits, reproducing every possible texture from silk to hair, from stained glass to Valencian tiled floors, crowns, the light from a child's skin or the matte tone of an old man's hand, books, bindings with their gold lettering, the sky and the pale brightness of the setting sun. Likewise, he portrayed a forest breeze, rays shining through the Gothic windows of a church and the whole reflection of a city on a stretch of lake in the background of a Saint Francis whose stigmata glowed with the precise amount of sheen in every drop of congealed blood.

Everything he saw in nature he conveyed with his brush: different types of rocks, variations of clouds and even depictions of skin diseases and no one, except Leonardo da Vinci, managed to paint the human eye with such precision, the eyelids, the veins and the steadiness of a fixed gaze.

Jan Van Eyck, Saint Francis receiving the stigmata (c.1440), Philadelphia Museum of Art

Erwin Panofsky demonstrated how, unlike his Florentine contemporaries, Van Eyck had no interest in applying the mathematical laws of perspective. In The Annunciation scene from the Ghent Altarpiece, the floor and ceiling beams not only do not converge, they do not even come close. In the Washington Annunciation, far from a single vanishing point inside the church depicted, there are several. Van Eyck found an empirical solution for the representation of a compelling space based on direct observation. With it, he came to create twofold perspectives, suggesting distances both panoramic with horizons as real as they are implausible and meticulously detailed - what Panofsky defined as the juxtaposition of his microscopic and telescopic gaze. And so, in the foreground are the interiors his characters inhabit, that intimacy that today fascinates us because we recognize in it our own world, the modern world of the individual and their things: gloves and carpets, musical instruments, lilies and easels and reading stands. That eagerness to portray everything, even what it is not necessary to show, is overwhelming. It is that same domestic and modern intimacy that will later be painted by the likes of Vermeer and De Hooch and Chardin, while in the background or somewhat higher up, another scene unfolds behind a window or on a balcony: a view of a Flemish city, its towers, belfries and streets lost in a horizon of lakes, blue mountains and tranquil skies. Landscapes both infinite and of pinpoint accuracy that in turn, centuries later, a young Ingres would paint in his 1806 "Portrait of Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière".

Jan van Eyck , Annunciation (detail)

Jan van Eyck, Annunciation (c.1430-35). National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Mademoiselle Rivière (c.1793-1807). Louvre Museum, Paris

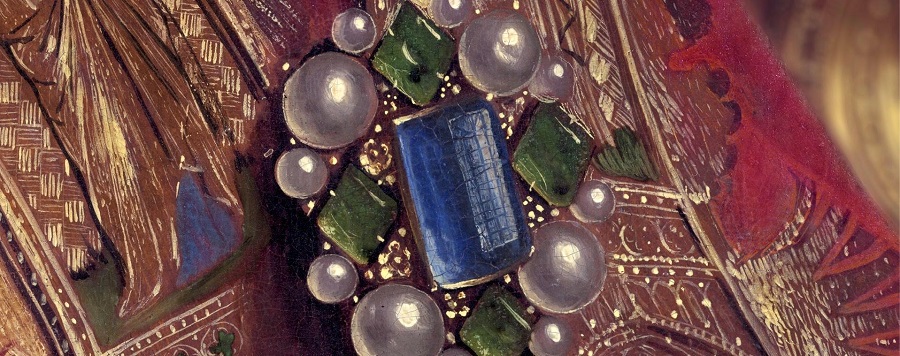

Van Eyck suffered from an obsessive fixation with the way light covers and forms images from reflection and refraction. The mirror must have permeated his world not only as an object, but also as a metaphor. Some of his knowledge came from observation, but in his time he was considered the first pictor doctus (illustrated painter) north of the Alps. He was familiar with classical authors, had read Pliny the Elder, was an expert in geometry, in archaeology, but above all, he knew optics, that Late Medieval science based on the discoveries of Arab mathematicians, such as Alhazen. Van Eyck used and perfected it in the development of an optical revolution that still impacts us emotionally today. The lighting of the Ghent Altarpiece corresponds to the natural incidence of light through the southern windows of the Vijd chapel. Throughout the altarpiece, the light falls from the upper right corner, like sunlight in the chapel on a sunny afternoon in late spring or early summer. The degree of consistency in the lighting of the entire altarpiece is exceptional. In the central God the Father figure, the jewels in his mitre, the focal point of the sceptre's quartz rock crystal and all the points of light in the gold brocade fabric show a high degree of photographic accuracy.

Marc De Mey, who explored Alhazen's influence on Van Eyck, was the first to point out the painter's tour de force conceiving of the alternating rows of pearls and crystal beads hanging from God the Father's gold brocade sash inscribed Sabaut (Lord Sabbaoth His Name): while the former absorb the light from the window, the glass ones project wide reflections of it.

There are hundreds of examples, from the metallic reflection of the red banners on the breast armour of St. Michael and St. George, to the reflection of an entire window in the huge central sapphire of the principal angel's brooch in the Angels Singing panel. The tracery of that window was scratched out with the very tip of his brush, saturated with white paint, using the sgraffito technique.

Angels Singing (detail), Ghent Altarpiece (1432), Saint Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent

What is also magical is the mastery the Flemish painter brings to painting the water flowing and splashing in the Altarpiece's fountain, as well as in The Virgin of the Fountain. Lighting plays a central role in its realism, but so does movement in the leap of every drop. The water flowing from the mouths of both sources is painted in fine, white, irregular and intermittent lines. It's as if Van Eyck had spent an afternoon with Bill Viola watching the water in his videos suspended in motion.

Jan van Eyck, Virgin of the Fountain (detail), 1439, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Flanders versus Italy, 1430

The exhibition pits Flemish paintings against their Italian contemporaries in a dialogue that reaffirms our question: What is it that makes Van Eyck seem like a comet flying over the 1430s in the European artistic firmament? Jacques Lassaigne and Giulio Carlo Argan have stated that the Renaissance was not a typical Italian movement that spread through other countries in a kind of progressive conquest, but rather a European phenomenon even though it happened differently in Flanders, Italy, France and Germany.

The beginning of the 15th century was witness to one of the greatest revolutions ever known in the history of painting. While Van Eyck paints the Altarpiece in Ghent between 1426 and 1432, Masaccio in Florence between 1426 and 1427 paints the Brancacci chapel, in the Carmine church. Italy favours form over concept; Flanders over experience. These two major works, created almost simultaneously by men so different in origin and tradition, are the pillars of a new painting.

Masaccio, The Expulsion From The Garden Of Eden (c. 1426-1427). Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

Masaccio continued to paint the walls of the Brancacci chapel al fresco with his Adam and Eve ejected and with anguished expressions in his Expulsion from Paradise but they cannot today touch their more serene, more disturbing namesakes in Ghent. There are, however, other revolutionaries in Italian optics: Gentile da Fabiano, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi ... with whom stylistic comparisons are inevitable, interesting: in Virgin and Child with Angels by Benozzo Gozzoli (1449-50) compared with van Eyck's Virgin of the Fountain (1439) the results from the same ultramarine pigment for the color of the Virgins' robes is very different: the tempera more opaque in the Italian and the crystalline glazes, much more intense in van Eyck. Also the enduring Italian penchant for gold leaf as opposed to the naturalistic focus of Eyck's painting which replaces the old-fashioned golden backgrounds with landscapes; the halos which cease to be large discs surrounding holy heads in favor of lighter golden rays; and gold objects which are no longer depicted with real gold but with yellow and brown paint to simulate light, form and texture.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Virgin and Child with Angels (c.1449-1450), Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail), Ghent Altarpiece

Absences

The penultimate room of the exhibition, dedicated to portraiture, is perhaps the most underwhelming. Tzvetan Todorov has said that when you walk through the halls of a large European museum, a radical change in the very nature of the paintings is visible as we pass, say, from 1350 to 1450. He explained that in northern Europe there was no Renaissance in the sense of a rediscovery of Greek and Roman civilization as a means of doing something new. Rather, the search for a new way to account for equally new experiences is what one observes. The common denominator in these changes is not the rediscovery of antiquity, but the discovery of individuality. Therefore, at that time, the individual portrait was invented, and has remained an art staple ever since. Men have taken the place of God in the system of universal symbolism.

Jan van Eyck, Baudouin de Lannoy (c.1435), Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museum, Berlin.

And so ends the exhibition, after the Crucifixions and the Annunciations, with the heroes of more recent times. There are six portraits of Jan van Eyck along with those of his Italian contemporaries Pisanello, Michele Giambono ...

Then, in the middle of the room, the only doubt about this extraordinary exhibition occurs to us: Where is Antonello da Messina with his delicate oils on wood? Moreover, where are the great Venetian Renaissance artists Vittore Carpaccio, Gentile and Giovanni Bellini?

We half-close our eyes and imagine ourselves in another room, solitary, painted blue, empty except for Man In A Red Turban (1433) by Jan Van Eyck facing Vittore Carpaccio's Man in a Red Beret (1485). Wouldn't that be a fight between Titans: a duel of two portraits gazing out at us, face to face.

As Jan van Eyck signed his motto: "Als ich can" (I did the best I could).

Left: Jan van Eyck, Man in a Red Turban, 1433. National Gallery, London. Right: Vittore Carpaccio, Man in A Red Beret, 1485, Correr Museum, Venice

Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution

Museum of Fine Art Ghent

Curators: Till-Holger Borchert, Maximiliaan Martens and Jan Dumolyn

Click here for a 360º Virtual tour of the exhibition

Virtual Live Tour conducted by Van Eyck expert and co-curator Till-Holger Borchert

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

Joan Miró was never one to play it by the book. As an artist, he lived and worked with the most notable creatives of his time and was open to the influence of any and all movements, works of art, schools and manifestos. But his work breaks away subtly from that of his contemporaries, invariably following its own unique and personal trajectory. By dint of constant creativity and his interest in all manner of artistic techniques, Miró left a legacy that is vast, versatile and full of coherence.

That most personal of all 20th century avant-garde art

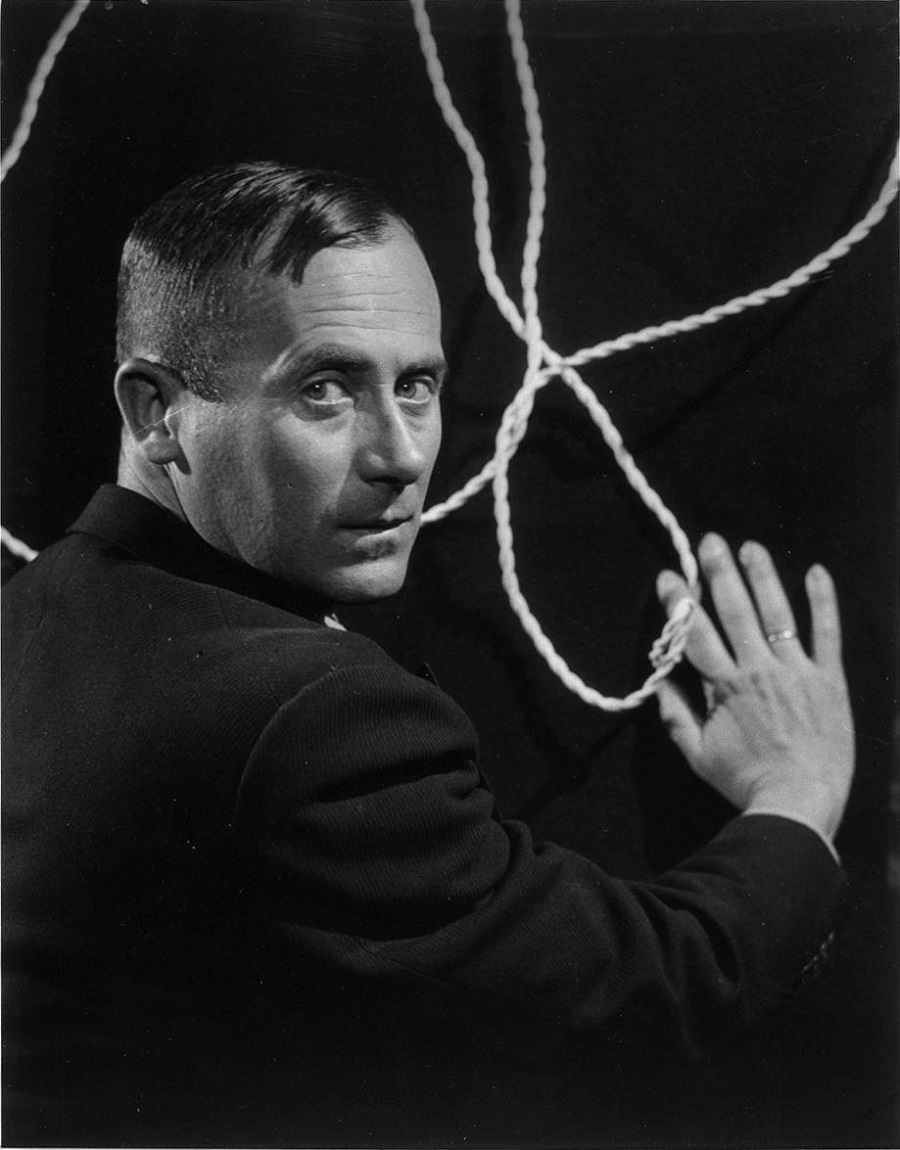

Photo of Joan Miró by Man Ray (1933). From www.museoreinasofia.es

Joan Miró was never one to play it by the book. As an artist, he lived and worked with the most notable creatives of his time and was open to the influence of any and all movements, works of art, schools and manifestos. But his work breaks away subtly from that of his contemporaries, invariably following its own unique and personal trajectory. By dint of constant creativity and his interest in all manner of artistic techniques, Miró left a legacy that is vast, versatile and full of coherence. Today, he is considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century on an international scale, his influence transcending the field of plastic art to impact and shape others such as graphic design and advertising. During his ninety years of life, Miró lived and worked in Barcelona, Mallorca, Paris and New York and his deep-seated love for home, especially Barcelona and the island of Mallorca, remained at the heart of his work, infused with the other landscapes that influenced his life.

"Femme, oiseau, étolie (Hommage to Pablo Picasso)", 1966-1973. From www.museoreinasofia.es

The love of art and discovery of modernity

Joan Miró i Ferrà was born in Barcelona in 1893 as the 19th century drew to a close and the arrival of the 20th augured a worrying shift in society, culture and artistic practices. Miró's artistic vocation was probably underpinned by his family's professions - his father was a goldsmith and watchmaker while his grandfather was a Mallorcan cabinet maker. The first known drawings by Miró date from 1901 when he was just 8 years old. During his university years, he combines Business with Fine Arts studies and in 1910 starts work as an accountant at a pharmaceutical company but his artistic disposition rebelled against the stasis of number-crunching and he resigns. At around the same time, he becomes ill with typhoid fever and goes to live for the first time at Mont-Roig, in a country house owned by his parents, and the surrounding Catalan Lowlands will remain forever in his heart and mind, becoming the protagonist in many of his works.

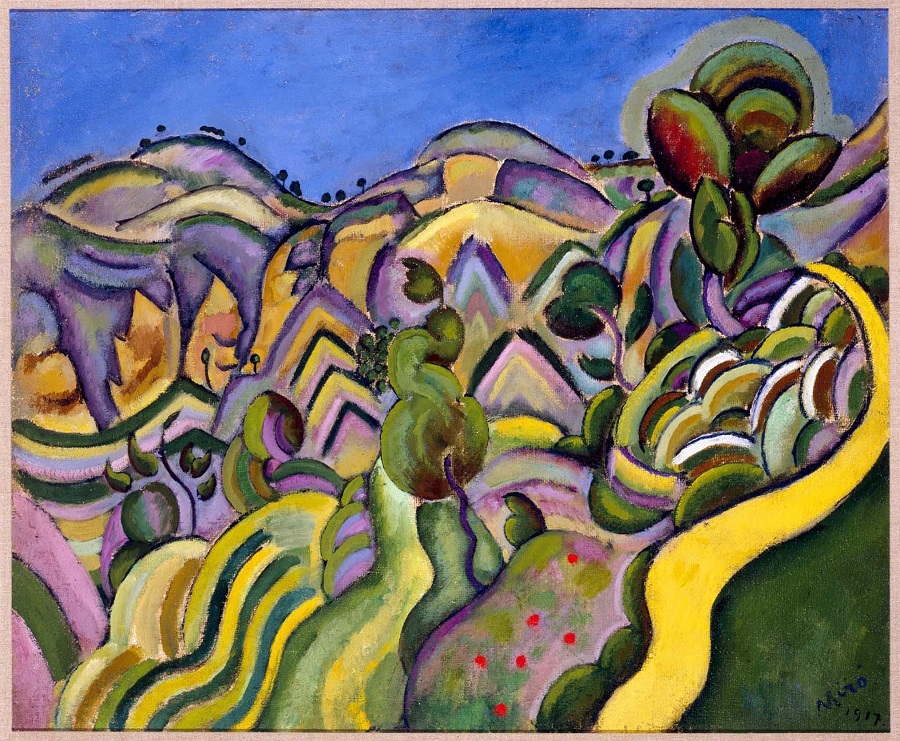

"Sirurana, el camí” (1917). Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid. From www.museoreinasofia.es

Convalescence allows Miró the time to reflect on his future and it is then that he decides to dedicate his life to painting and enrolls at the Francesc Gali School of Art where he first comes into contact with the circle of Catalan artists who will later become his friends, colleagues and art dealers. These are years of passion and youth, of painting live models and sharing studios with other artists. They are also years of discovery: Dadaist art and avant-garde Catalan and French publications spark the young Miró's interest.

The Paris Years

In the early 1920s and after his first exhibition at the Dalmau Galleries belonging to his friend and first dealer Josep Dalmau, Miró moves to Paris, where he works at Pablo Gargallo's studio. During his months off, he returns to Mont-Roig which, along with Paris, Barelona and New York, constitutes the nucleus around which his work would be structured. These were exciting years during which he meets Picasso, André Masson, Ernest Hemingway, André Breton and Paul Éluard, among other notable figures from the intellectual and artistic elites of the time. Miró works on projects above and beyond mere painting, such as his collaboration with Max Ernst on the costumes and staging for the ballet "Romeo and Juliet". It is also at this time that he creates his first "Spanish Dancers" (1928), Dadaist-inspired collages that will mark his later work. From 1930, Miró shows a growing interest in other disciplines, such as bas-relief and sculpture, which will come to feature more prominently in the ensuing years than his painting although he never abandons it altogether.

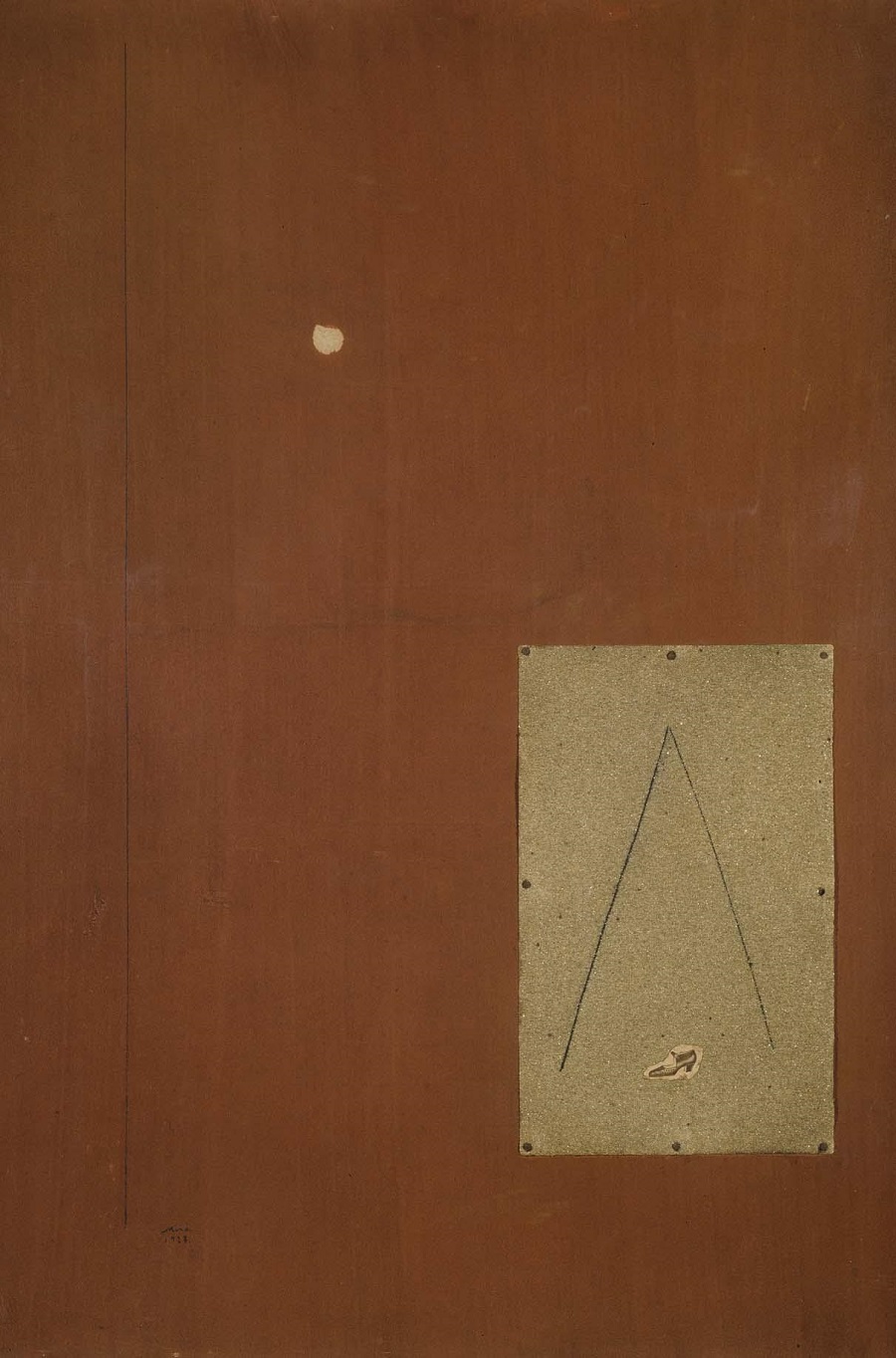

"Spanish Dancer I” (1928). Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid. From www.museoreinasofia.es

Collages, objects and murals

Joan Miró working on the mural "The Reaper" (1937). From www.20minutos.es

From 1931, Miró, dividing his time between Mont-Roig, Paris and Barcelona, adds another new and fascinating location - New York, where Pierre Matisse, son of the French Fauvist painter and engraver Henri, will be his representative. During these years, Miró increasingly expands the spectrum of disciplines used for his work, creating etchings, collages, assemblages and paintings on masonite. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forces him, along with his family, to move to Paris where he commits to the Republican cause by painting, in 1937, a large mural, "The Reaper (Catalan peasant in revolt)", for the Spanish Pavilion at that year's International Expo. The mural has since disappeared and black and white photographs are all that survived.

A passion for sculpture

"Personnage" (1974) from the exhibition Joan Miró: Sculptures, organised by the Centro Botin de Santander in 2018. From ABC

From the 1920s onwards, Miró dedicates a large part of his time to sculpting. His three-dimensional works took their inspiration from his declared passion for 'objects', so much so that he came to stockpile hundreds of them in his studio. In the 1940s, the artist cast his first bronzes and began experimenting with different materials and media. Up until the very end of his life, Miró would develop his work on sculpture and compile an enormous portfolio. In the 1960s, Alberto Giacometti advised him to paint some of his bronzes, a suggestion that resulted in some magnificent pieces, such as "Personnage" (1967). In addition to bronzes and painted figures, Miró also worked with marble and ceramic-clad concrete. His last monumental sculpture, "Dona i Ocell" (1987), is a fine example of his mastery of materials.

International art that lives on

From the 1950s onwards, Miró consolidates his international reputation and his fame begins to spread worldwide. He settles definitively in Palma de Pallorca where he undertakes his first ever ceramic pieces, in collaboration with the ceramicist Josep Llorens Artigas. He will employ this technique in enormous murals that can still be seen and admired in numerous major cities, those at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris (winner of the Guggenheim International Award), Harvard University and Barcelona Airport to name but a few. 1975 sees the inauguration of the Miró Foundation in Barcelona, tasked with managing and disseminating the artist's legacy. Miró continued to work for the remainder of his life and died aged ninety in 1983, widely regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

Mural "La Luna" (1958) in collaboration with Josep Llorens Artigas at UNESCO headquarters, Paris. From www.unesco.org

EXHIBITIONS

Hommage to Miró (1974)

This exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris was the last retrospective of his work to take place during Miró's lifetime. Over forty years later, in 2018, the Grand Palais was to inaugurate another large exhibition dedicated to the artist, "Miró, the colour of dreams", showcasing more than 150 of his works.

Miró and the object (2016)

Organized by the CaixaForum Madrid, the aim of this exhibition was to explore new facets of Miró's universe through objects: their poetics, their expressive possibilities and the "soul" that Miro was always able to find in them. The exhibition opened in Madrid after first showing at the Miró Foundation in Barcelona and covers the long artistic period from the 1920s to the 1970s. Some of the works on display (for instance "The Toys", 1924) were being seen in Spain for the first ever time.

Miró, the colour of dreams (2018-19)

As mentoned above, this exhibition at the Grand Palais was in honour of the work and figure of Joan Miró forty four years after the previous retrospective in the 1970s. As his personal friend and the exhibition's curator Jean Luis Prat commented at the time: “Miró was probably deeply affected by 50 years of history marked by two world wars. These formidable events and the questions he asked of men, of himself and of his homeland have coloured his work."

Birth of the World – MoMA (2019)

In early 2019, the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) organized a grand exhibition of the artist's work with key pieces from its magnificent collection and several exclusive loans. The exhibition centres the painting "The Birth of the World" as its focal point. The display comprised almost 60 oils on canvas, drawings on paper, engravings, illustrated books and objects.

BOOKS

"Miró". Jacques Dupin, 1961

Constantly revised, updated and reworked, the monograph published by Jacques Dupin in the early 1960s is essential reading for anyone wanting to know all there is to know about our Catalan artist. The biographer completed the book including Miró's work over the subsequent two remaining decades of his life, thanks to the excellent relationship he enjoyed with Miró's family and unprecedented access to work carried out by historians, curators and art experts. In 1993, another revised edition was published which is still considered, today, one of the most fundamental texts on the life and works of Joan Miró.

"Miró". Janis Mink, 1999

Taschen publishing house, the benchmark in art and artist monographs, published a 1999 biography of Joan Miró by Janis Mink. With hundreds of illustrations and magnificent attention to detail, the book covers the artist's trajectory of almost 70 years - from his Surrealist-style automatic drawings to the assemblage-sculptures he constructed from objects. The book is careful to respect Miró's idiosyncrasies as an unclassifiable artist and figure who resisted being pidgeonholed into categories, trends or schools.

“Joan Miró. The Road To Art”. Pilar Cabañas, 2013

Much has been written about Joan Miró's life and work but even so, in 2013, Pilar Cabañas managed to shine a whole new light on the artist's work and write a book that is vital for understanding it. Basing her point of view on the principles that govern Miró's work, the author provides us with the guidelines for understanding the man as a human being and as an artist. Cabañas delves into issues such as what drives his creativity, the reasoning behind his art and the exploration of sadness, loneliness and pain in his work, among others. With Miró as a starting point, Cabañas guides us through art in general as a path to transcendence and the essence of humanity. The text is enriched by the participation of Ignacio Llamas who designed the edition.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Joan Miró: biography, works, exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

French artist Christian Boltanski is an old acquaintance of the Spanish public. His 1988 Madrid exhibition – “El Caso” (The Case) - was a curious and disturbing suite of works expressly conceived of for the Reina Sofia Museum as a follow-up to his “Detective” exhibition of 1972. From articles in El Caso, a weekly journal of crimes and misdemeanors (1952-1997), and the Reina Sofia building’s origins as a hospital, the artist sought to create a world that would unnerve viewers finding themselves surrounded by portraits of the murderers and victims featured on newspaper pages alongside starched white sheets, folded and piled up as if by nurses.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

French artist Christian Boltanski is an old acquaintance of the Spanish public. His 1988 Madrid exhibition – “El Caso” (The Case) - was a curious and disturbing suite of works expressly conceived of for the Reina Sofia Museum as a follow-up to his “Detective” exhibition of 1972. From articles in El Caso, a weekly journal of crimes and misdemeanors (1952-1997), and the Reina Sofia building’s origins as a hospital, the artist sought to create a world that would unnerve viewers finding themselves surrounded by portraits of the murderers and victims featured on newspaper pages alongside starched white sheets, folded and piled up as if by nurses. He created a symbolic and metaphorical world from his own particular understanding of existence where subjectivity is a blurred line between erased , anonymous images and the horror or the evil that can be concealed.

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

With that exhibition and many others, both before and after, Boltanski has become an artist of note and now, thirty-five years after his first retrospective at the Museé National d'Art Moderne in Paris, the Centre Pompidou pays him homage with a large exhibition featuring the themes that have been his constant companions since 1967: collective memory, the passage of time, loss, oblivion, forgetting, chance and, above all, the human condition.

In his work, Boltanski projects new light onto all that is known, giving the historical fact of the Holocaust a new interpretation by framing it within his quest to interrogate everything, from feelings about existence to an existence that does not respond.

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

He reminds us of the ephemerality of life versus the definitiveness of death and does so using photographs, videos, tin boxes stacked or embedded in walls like cremation urns in niches, some of them with small portraits, mostly of children. But also with display cases, newspaper clippings, notes, family photos, black monoliths that recall funerals, curtains enclosing tiny spaces, black clothes forming a morbid mountain of death. All this within a labyrinthine journey around the museum that never stops asking questions. Spirits lost in a forest of souls.

Dim lighting, disturbing noises that at times sound human and challenge the silence of the viewer in the face of so much desolation. The staging corroborates and enriches the artist's intention with each of the exhibits, all of which become channels of communication.

Christian Boltanski. Photo: Maira Herrero

“Nothing answers us, but that silence, the voice of that silence, we hear it, and it terrifies us, 'the eternal silence of these infinite spaces' that Pascal speaks of.” Emmanuel Levinas

Boltanski once said that his exhibitions create experiences, seek to move the visitor and let them come to their own conclusions. Never a truer word was spoken.

Christian Boltanski: Faire son temps

Centre Pompidou

13 November 2019 - 16 March 2020

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Christian Boltanski: Doing One's Time - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

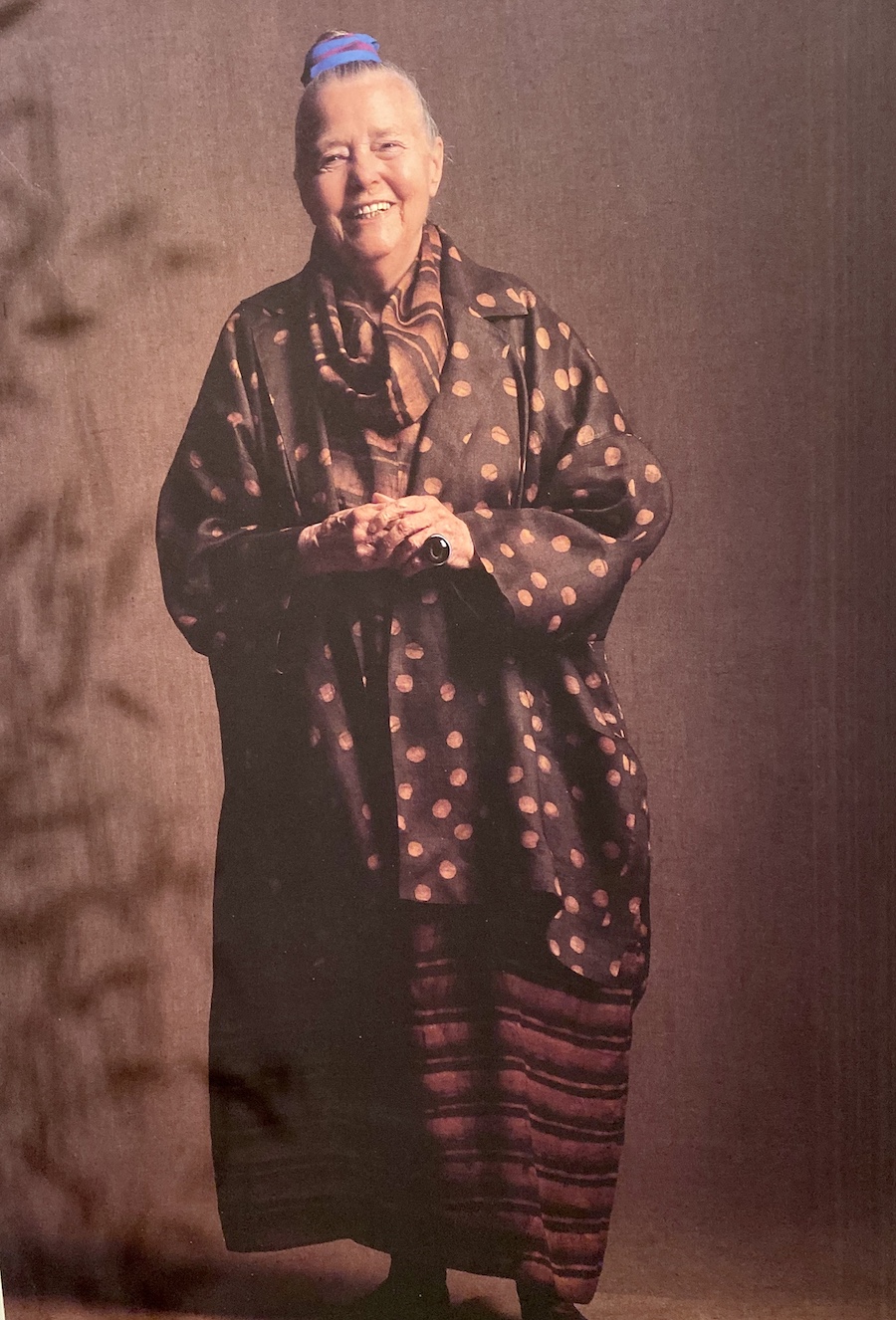

Art is in everything, art is in life and it expresses itself on every occasion and in every country. Charlotte Perriand, iconic figure of twentieth century design, demonstrates yet again the importance and influence of her work in a grand exhibition on display until February 24 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Perriand changed the way we inhabit domestic spaces, creating a world full of possibilities unfettered by traditional notions of what a home should be.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Left: Charlotte Perriand at La Vallée, circa 1930 © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP. Right: Charlotte Perriand reclines on « Chaise longue basculante, B306 » (1928-1929) – Le Corbusier, P. Jeanneret, C. Perriand, circa 1928 © F.L.C. / ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP

“Art is in everything, art is in life and it expresses itself on every occasion and in every country.” Charlotte Perriand

Charlotte Perriand, iconic figure of twentieth century design, demonstrates yet again the importance and influence of her work in a grand exhibition on display until February 24 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Perriand changed the way we inhabit domestic spaces, creating a world full of possibilities unfettered by traditional notions of what a home should be. She made use of technical skill, industry and the most advanced materials for her designs. Parts from bicycles, cars and even airplanes were a source of inspiration that would lead to her becoming, over time, a pioneer in the mass production of her own designs.

Almost the entirety of the Frank Gehry-designed gallery has been given over to the exhibition on a chronologically arranged route that welcomes the visitor with a large painting by Fernando Leger, “Le transport des Forces”, and two of Perriand's most iconic pieces, the Chaise Longue basculante LC4 and the B302 Swivel Chair, long and erroneously thought to have been designed by Le Corbusier alone.

As well as Leger, other artists features alongside Perriand throughout the whole tour are, Picasso, Laurens and Delauney.

Building modernity, exploring Nature and engaging with other cultures are just a few of the highlights of the Exhibition that define the work of an intelligent woman devoted to her ideas and profession and whose unwavering dynamic vitality endeared her to everyone she met. A tireless traveller, she absorbed life with such intensity that it is sometimes difficult to keep pace with her.

In 1926, a recent graduate and excited by Le Corbusier's theoretical work on new cities and alternative ways of living, she knocked on the door of the studio that the renowned Swiss architect shared with Pierre Jeanneret, the outcome of which was that infamous quote: “Miss, we don’t embroider cushions here”. A year later, Le Corbusier recanted and offered her a contract, having seen, at the Salon of Decorative Artists, her piece Le Bar sous le toit, a cocktail bar that Perriand had designed for her own apartment. Thus began an intense collaboration that would endure throughout the lives of these two innovators. Perriand writes in her memoirs that her role in Le Corbusier and Jeanneret’s studio was to bring the ideas of the two great architects to fruition. She was a practical woman and one capable of solving any problem with her vivid imagination, filling what Le Corbusier called “machines for living” with humanity. In 1952, Le Corbusier called her to design the interiors of what are known as his Unité d’habitation housing developments in Marseille and Berlin. The result can be seen in the Exhibition and illustrates that she knew precisely how to convert those minimal spaces into cosy places, incorporating the first ever compact modular kitchen prototype.

One of the key pieces in the Exhibition is a recreation of the interiors project for the 1929 Autumn Salon, L'Équipement Interieur d’une Habitation, which she created in collaboration with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret. Here, the visitor can interact with the furniture and understand how the arrangement of objects in a space creates the ambience that turns a home into a comfortable one.

In 1929, the pricking of her social conscience led her to participate in the creation of the Union of Modern Artists (UAM), in which Mallet-Stevens, Miró, Calder, Delauney and Chareau also participated. What they sought was the coming together of all arts to respond to the political and societal problems of their time. The Republic of Spain pavilion at the 1937 Paris exhibition was a perfect reflection of the aims of UAM - architecture, sculpture, painting and photography together in a joint portrayal of the tragedy of war. Its curator was the architect José Luis Sert, a great friend and collaborator of Perriand’s, who is remembered in the exhibition with a display of his photographs taken during the Spanish Civil War and a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica, among other items. Both architects shared the same social concerns and collaborated on the design of minimalist housing. In 1933, they participated in the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) where the Athens Charter was drawn up, the widely-known manifesto on optimal conditions for urban living.

A full-scale model of another of Perriand’s iconic works, 1934’s The House On The Edge of the Water, rests on stilts outside the Foundation on and beside a water feature so that visitors can visualise the meaning of the project, intended as a holiday home for families with little money to spare. A kind of self-assembly cabin than can be dismantled, supported on stilts and divided into two symmetrical spaces: one, the living area and the other to sleep in, both with sliding doors opening onto a terrace protected by a canopy collecting rainwater. Again, Perriand is thinking about functionality and aiming to reach the most needy by building a world that is simpler, more humane and closer to nature.

She was also an accomplished photographer who scrutinized Nature through her camera lens, finding solutions for many of her creative ideas there. The sea and the mountains were recurring themes in her snapshots and the inspiration for a series of projects on mountain shelters. In 1938, her Tanneau Mountain Refuge, measuring eight square metres and sleeping six people, was built. “I love the mountains deeply,” she said. “I love them because I need them. They have always been the barometer of my physical and mental equilibrium.”

Her time in Japan and Indochina are very well illustrated in the Exhibition with designs incorporating elements from the East such as indigenous types of wood, bamboo, lacquer and fabrics that reinforced the links between creation and tradition. Brazil, where she got to know other renowned architects and the exuberance of their designs, was another turning point in her career.

The crowning moment of her career would come with the Les Arcs project, a huge apartment complex in the French Alps, with a sleeping capacity of 30,000. Perriand, in a display of ingenuity, developed what has been called minimalist compartments or cells. The interiors were mostly built from prefabricated pieces and boasted large windows with stunning views that brought nature in from outside. A large model serves to help the viewer understand Les Arcs as the culmination of the whole repertoire of Charlotte Perriand’s ideas.

The tour ends with Perriand's last ever commission – 1993’s Maison de Thé for UNESCO’s Paris headquarters: a wooden circle supporting eighteen bamboo canes creating a 4.5 metre high space covered with a domed canopy of leaf silhouettes. A delicate, organic work to celebrate the Tea Ceremony.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World

Louis Vuitton Foundation

2 October 2019 - 24 February 2020

(Translated form the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Le Monde Nouveau de Charlotte Perriand - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

On a scale of difficult to … how does one even begin to guess what was going through Leonardo da Vinci's mind on seeing a woodpecker for the first time? "Describe its tongue," the painter asks himself in one of the many little notes scribbled in the margins of a notebook ... "The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril." In the concluding pages of his book, Walter Isaacson (New Orleans, 1952) establishes an imaginary dialogue between his reader, Leonardo and himself in which he offers us a clue: "There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. But I thought maybe that you would want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.”

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Lady with an Ermine (1490), National Museum of Krakow

On a scale of difficult to … how does one even begin to guess what was going through Leonardo da Vinci's mind on seeing a woodpecker for the first time? "Describe its tongue," the painter asks himself in one of the many little notes scribbled in the margins of a notebook ... "The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril." In the concluding pages of his book, Walter Isaacson (New Orleans, 1952) establishes an imaginary dialogue between his reader, Leonardo and himself in which he offers us a clue: "There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. But I thought maybe that you would want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.”

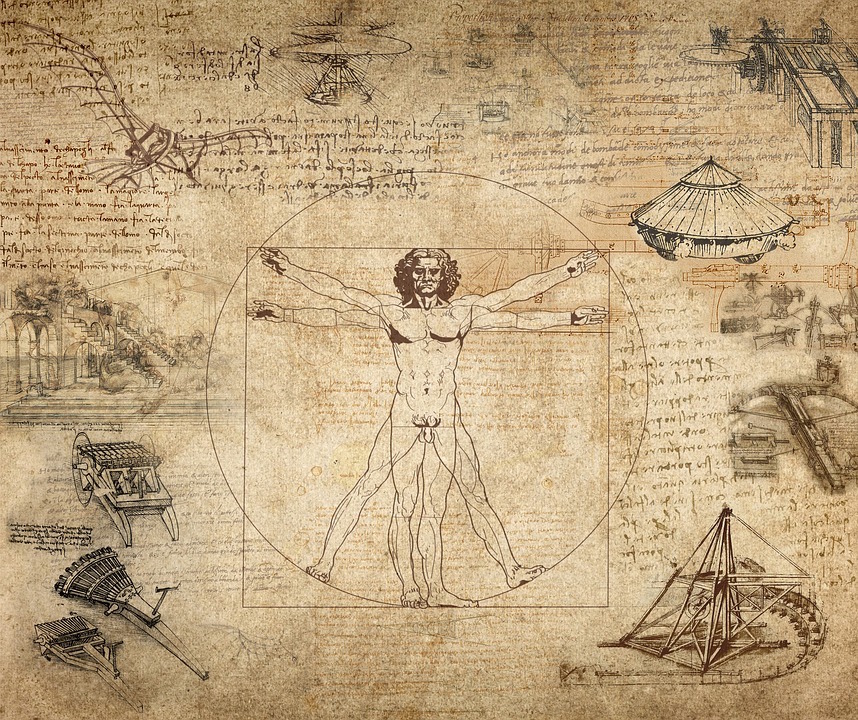

This is at the end of the book and also at its heart. The word "curiosity", repeated throughout its 624 pages, is one of the axes on which the description of the genius that was Leonardo (1452-1519) revolves and why the author acknowledges that this biography is based not on his paintings but on his notebooks. He believes the 7,200 pages of miraculously preserved notes, drawings and sketches are what hold the key to the enigma of "the most curious man in history", as Kenneth Clark dubbed him.

Vitrubian Man (1490), Accademia Gallery, Venice

Leonardo's fascination with the world and his observations of it were what predominated his thoughts and unbounded imagination. The notebooks are the record of a stubborn, daring, unstoppable mind. The author wants to breathe all of this into us, as if, through a kind of mental gymnastics, we readers could also grasp some of Leonardo's brain. The genius of one of history’s greatest visionaries was born of abilities that we ourselves possess and are also able to stimulate. His curiosity, like Einstein's, was mostly concerned with phenomena that wouldn’t even occur to most people over the age of ten: How do clouds form? Why do our eyes only see in a straight line? What makes us yawn?

Isaacson, a former Time Magazine editor, is obsessed with talent. The New Yorker writes that this book is a study on creativity, how to define it, how to achieve it. And this is what led its author to choose the figure of Leonardo to follow on from his previous biographies of Einstein, Kissinger and Benjamin Franklin, all of whom established connections between different disciplines: they knew how to link observation and creation. In his penultimate biography, Isaacson quotes Steve Jobs, for whom Leonardo was a hero: "He saw the beauty in both art and engineering and his ability to combine them made him a genius.”

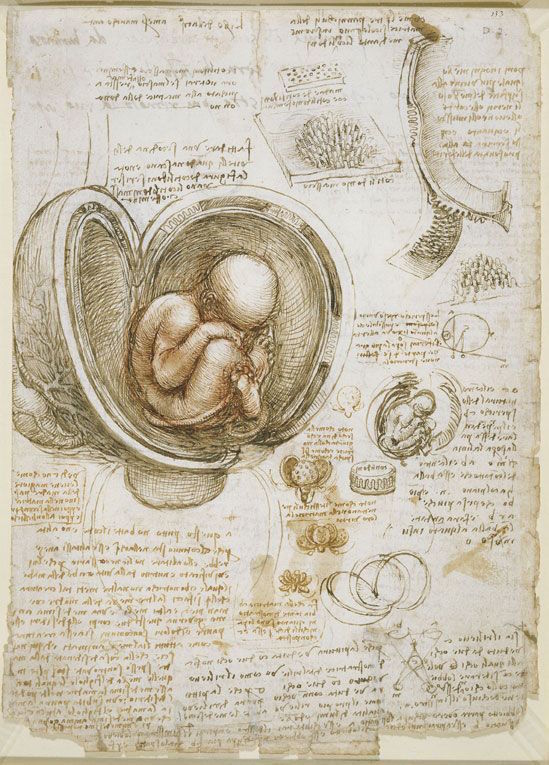

Foetus in the womb, inspired by the dissection of a pregnant cow (circa 1511), Royal Collection, Buckingham Palace

The desire to know

This book portrays, essentially, a man consumed by the desire to know. A son born out of wedlock, vegetarian, homosexual, fashion buff with a penchant for dressing in pink and linen, his love of animals preventing him from wearing anything dead on his person. But did he ever live with his mother? Who did he love and, above all, who loved him? There are chapters dedicated to his childhood and his death in the arms of Francis I in Amboise.

It would seem that 1452 was a fine time for a child with such skills to be born: Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. The Ottoman Turks were about to invade Constantinople, which led to mass exile to Italy by scholars laden with manuscripts containing the ancient wisdom of Euclid, Plato, Aristotle ... And just a year separated the births of Christopher Columbus, Americo Vespucio and Leonardo.

La Belle Ferronière (1480-1495), The Louvre, Paris

Leonardo had almost no formal schooling: self-taught, from a young age he would tie a notebook full of enigmatic and invariably undated writing to his belt. He wrote from right to left, thus producing his specular calligraphy - "It should be read with a mirror," Vasari wrote - using his left hand to move backwards without smearing the ink. The pages are full of wild leaps, from the description of a mechanical problem to the curl of a lock of hair. However, it was there in those pages that he wound up weaving the key to his art: the interconnection between Nature, the human being and the Earth. He accompanied his drawings with texts whose shapes can be found similarly in branching trees, the arteries of the human body and in rivers and their tributaries ... whilst at the same time, in some page corner, he jotted down the formula for hair dye. This tower of Babel, this medley of multicoloured splashes of ink, leads us to marvel at a universal mind which scoured the arts and sciences with abandon and awe and in so doing perceived the connections that occur in the universe.

The Virgin of the Rocks (detail) (1483-86), The Louvre, Paris

Birds, waves

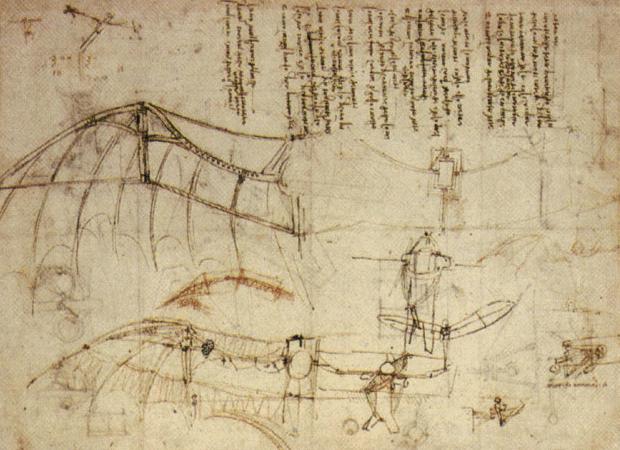

And so Leonardo set to observing birds, researching how they flew and even the possibility of designing machines that would allow humans to fly. He painted the elegance of the birds as they turned, soared and manoeuvered in the wind. He pioneered the use of arrows. No scientist before him had shown how birds were able to remain aloft. And he corrected Aristotle: "In order to give the true science of the motion of birds within the air, it is necessary first to give the science of the winds, which we shall prove by means of the motions of water within itself." Not only did he understand fluid flow patterns and their dynamics but his ideas predated those of Newton and Galileo. He also observed the flight of a partridge: "When a bird with a wide wingspan and short tail wants to take off, it will lift its wings with force and turn them to receive the wind beneath them."

Articulated wings, emulating those of birds

In the meantime, he was also studying the Earth as a planet. In 1508 he summed it all up in his notebook, the Leicester Codex. In it he wondered: Why do springs originate in the mountains? Why do valleys exist? What makes the moon shine? How did fossils make their way up mountains? What makes water and air whirl? And the most surprising, why is the sky blue?

The current owner of the Leicester Codex is Bill Gates so, although Isaacson makes no reference to it, some of its digitalized pages are used as screensavers by Microsoft.

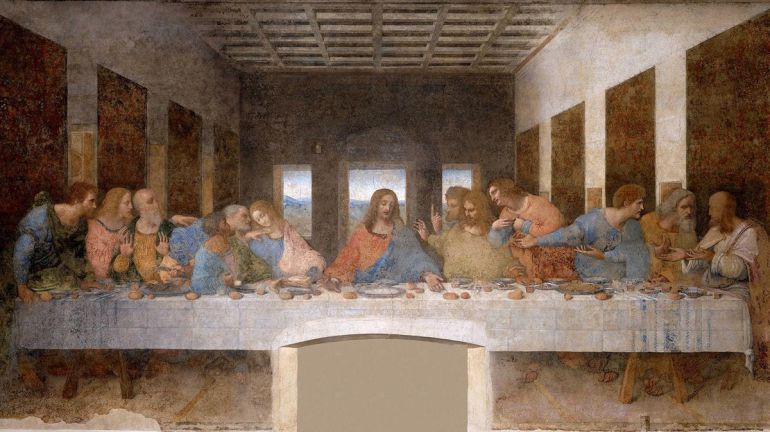

His studies on the movement of water also led him to understand that of waves. He noticed that they don't necessarily push water forward. Sea waves and those caused by a stone falling into a pond advance in a certain direction but all these what he called "tremors" do is cause a momentary swell before returning to their starting point. He compared them to the undulations caused by the wind in a cornfield. He even believed that emotions could also spread in waves. One element of the narrative of the Last Supper is the waves of emotion that Jesus causes after saying, "Truly I say unto you that one of you will betray me."

The Last Supper (1495-97), Refectory of Santa María della Grazie, Milan

Also blended seamlessly through Isaacson's pages are paragraphs on many of Leonardo's works of art, his discoveries, his techniques and the description of his paintings from Salvator Mundi and the Virgin of the Rocks to the Man of Vitrubio and The Last Supper. In Ginevra De'Benci's portrait, Leonardo portrays a melancholy young woman against a background of juniper bushes (Ginevra meaning juniper in Italian). Leonardo applied not old-fashioned tempera but hundreds of layers of oil paint so as to make Ginevra's curls and the button at her neck appear to be forged from light. And let’s not forget the similarity of the colours of her dress to the landscape in the river water and the shadows cast by trees. "Ginevra has remained at one with the land and the river that binds them."

Ginevra de' Benci (1474-76), National Gallery of Art, Washington

Human anatomy

In 1508, in a Florentine hospital, he would strike up a conversation with a hundred-year-old man who was to die a few hours later. Leonardo dissected his body. On one of his notebook pages, above several sketches of the muscles and veins of a partially skinned corpse, he made a note of the centenarian’s face. Then, over the next 30 pages, he proceeded to make notes of what he saw. His rudimentary instruments for dissection enabled him to discover, layer by layer, the body while the body, being untreated, decomposed. First he showed the elderly man’s superficial muscles, then he removed the skin and showed the inner muscles and veins. Of all the related muscles and nerves, the ones controlling the face seemed to him the most worthy of study. He drew a cross-section of the spinal cord and all the nerves leading from the brain. He ascertained from the corpse that it is the cheek muscles that move the lips. They were the first known examples of the scientific anatomy of the human smile. At the time, Leonardo was working on the Mona Lisa.

Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster, 2018

624 pages

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Leonardo Da Vinci ~ an infinite curiosity - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Ángeles Blanco

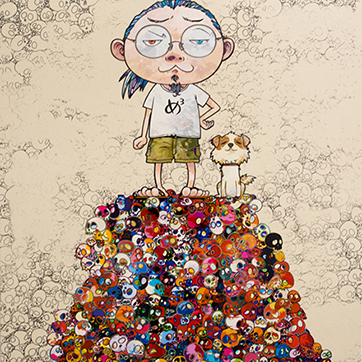

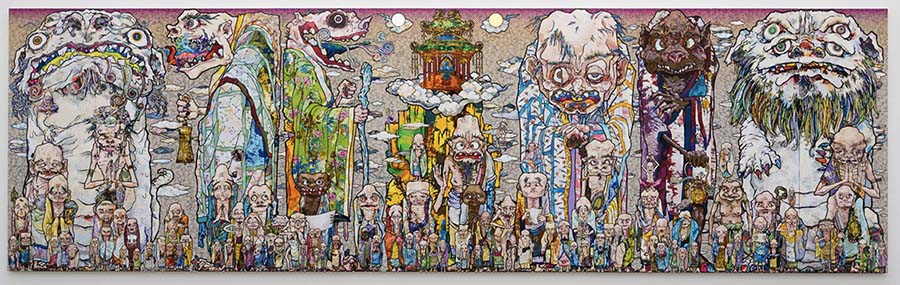

Artists nowadays don’t have to take a vow of poverty in order to be successful or to garner recognition. A good example of this is Takashi Murakami, one of the most popular Japanese artists on the international art scene. About his origins he admits: "I wanted to be successful commercially. I just wanted to make a living in the world of "entertainment" and I was very clear about my strategy and what kind of paintings I’d have to do to that end, but since then my motivation has changed."

Photo: "Our Gang", available from http://www.japantimes.co.jp/, 26 April 2013

Known as the Japanese Andy Warhol because they both managed to turn art into merchandise and attract mass culture, this fact has led some to see his art as simply a business. But Murakami interconnects high art with popular culture, arguing that art forms part of the economy. He justifies this by saying: "Japanese people accept that art and commerce will rub shoulders; in fact, they’re surprised at the rigid and pretentious hierarchy of Western “high art"."

Photo (right): Takashi Murakami, available at http://www.dw.com/

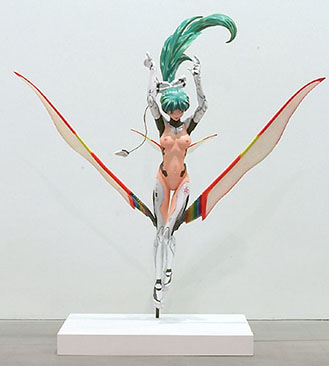

Born in Tokyo in 1962, he left Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music in 1983 with a PhD in “nihonga”, whereby paintings follow traditional Japanese artistic conventions both in technique and in subject matter and materials. He incorporates elements of Japanese culture from different eras in his work. On the one hand, traditional Buddhist iconography, 12th century painting, Zen painting and composition techniques from the 18th century Edo period, from which he adopts the use of fantastical and unusual images. On the other, he borrows contemporary popular elements of expression, such as Japanese “anime” (animation) and “manga” (comics) and also American pop art. He reworks this diversity of influences into myriad artistic media and formats, his work ranging from paintings reminiscent of cartoons to quasi-minimalist sculptures, giant inflatable balloons, films, watches, T-shirts and other mass-produced merchandise.

Photo (right): Balloons, available at http://www.terihaartadvisory.com/

His works are colourful and engaging and he uses his wide knowledge of Western art, working from the inside out to represent “Japaneseness” as a tool to bring about a revolution in the art world. "I believe that all artists should have strong, dark emotions within them in order to create works that have energy", and, according to Murakami, the force behind his work is for him "to become a living example of the potential of art."

Photo (right): Crazy Z, available at http://www.artnet.com/

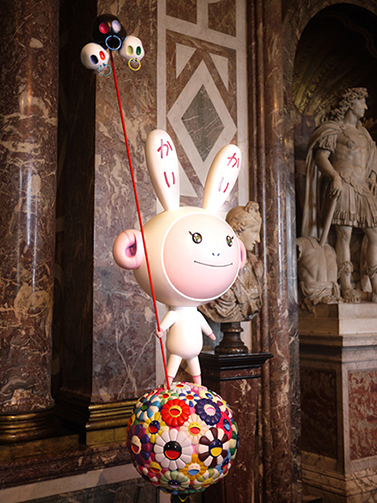

Murakami began to make a name for imself in the 1990s, following Japan's economic crisis of the late 1980s, hand in hand with the Nipponese Neo-pop generation. His work has been exhibited in prestigious museums around the world, such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Bard College of Art Museum and the Palace of Versailles.

Photo (right): Tongari-kun, available at http://malaysiafinance.blogspot.com.es/

In 1996, he founded the Hiropon factory in Tokyo, which in 2001 became Kaikai Kiki Co. Ltd, an international corporation employing over 100 employees and dedicated to the production, management and commercialization of the art created by this multifaceted artist and also to support and promote up and coming new artists: twice a year, he organizes GEISAI in Tokyo, an art fair that allows young artists to exhibit their works, many of whom have ended up working for him. His company develops diverse projects with real market strategies that cross the boundaries of artistic circles to reach the general public, using mass production, merchandising, manufacturing and made-to-order corporate designs, some of them for prestigious brands such as Louis Vuitton and Issey Miyake.

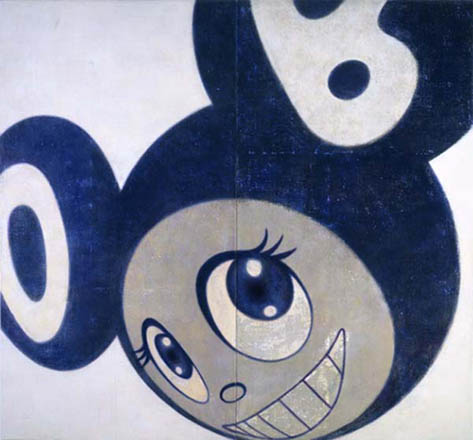

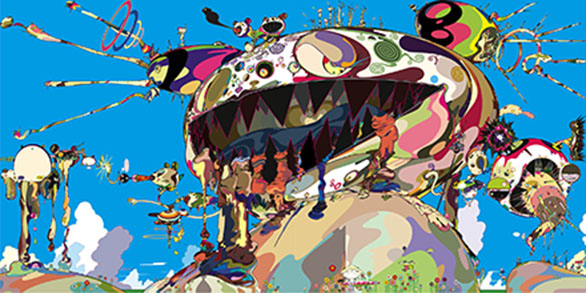

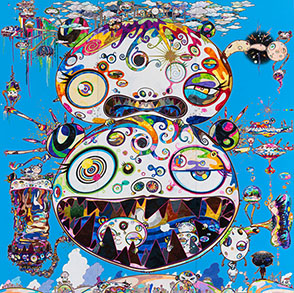

Some of Murakami’s characters have been evolving since the beginning of his career. His alter ego Mr. DOB, for instance, was born in the 1990s as a cute DNA helix (ZaZaZaZaZaZa, 1994) but he has gradually morphed first into a disturbing creature (Tin Tin Castle, 1998) and then a huge monster symbolizing society’s cravings for consumerism (Tan Tan Bo vomiting, 2002). He is one of Murakami’s recurring characters, a kind of logo or trademark, who is reproduced on T-shirts, posters, keychains, etc and has even been brought to life through 3D sculptures all over the world.

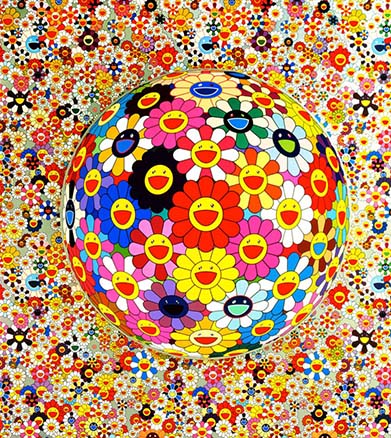

In 2000, Murakami organized a Japanese art exhibition entitled Superflat, linking contemporary Japanese pop culture with Japanese historical art, which gave way to a movement towards mass-produced amusements. This gave rise to the postmodern cultural current of the same name, which refers to its flat style and the absence of depth or persepective in his compositions. This aesthetic, in which everything is depicted in two dimensions, offers an external interpretation of postwar Japanese popular culture through its “otaku” subculture, a term that designates what in the West we would call “geek” or “nerd” and which refers to people obsessive about their hobbies. Hence his invention of the term "POKU", a portmanteau of “pop” and “otaku”: "Everyone works to make a living. Me too. And I hoped that some people would be interested in my art if I offered an expression of it like Poku culture because it's fun."

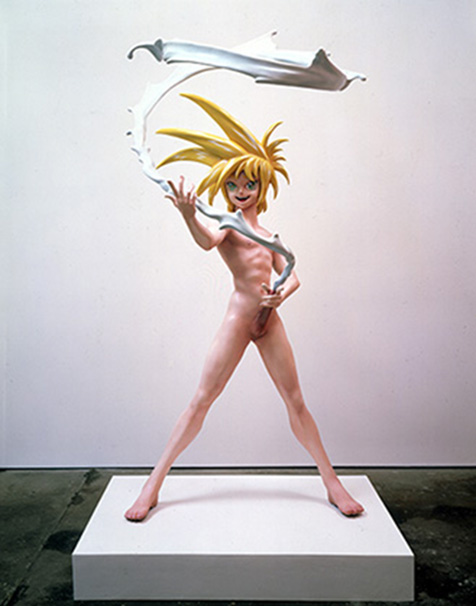

Examples of his work from this period here are Miss Ko2 (1997), a stylized anime-like waitress who wants to be a singer; Hiropon (1997), a young woman with unfeasibly large breasts; My Lonely Cowboy (1998), a naked teenage boy; PO + KU Surrealism Mr. DOB (1998), a large-scale triptych in which his typical superflat monochrome background is broken up by animated images of bulging eyes and razor-sharp teeth; or one of his larger sculptures, DOB in the Strange Forest (1999).

From 2000 on, Murakami has been creating other self-portraits in addition to Mr. DOB: between 2003 and 2005 Mr. Pointy and the Four Guards, based on the four Buddhist Protector deities; in 2004, Inochi, a teenager reminiscent of Spielberg's legendary E.T.

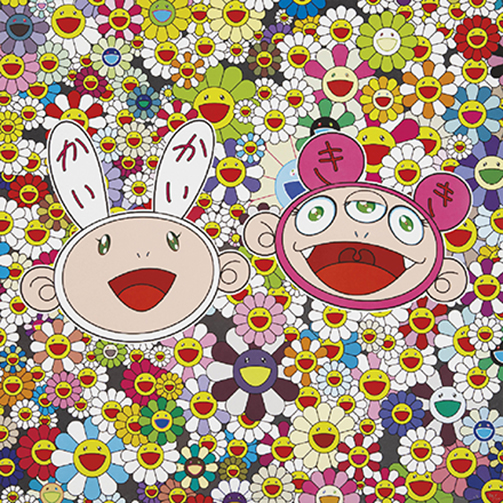

The cute Kaikai and Kiki, whose names derive from the term “kikikaikai” which means "strange but captivating" are the author's spiritual guardians.

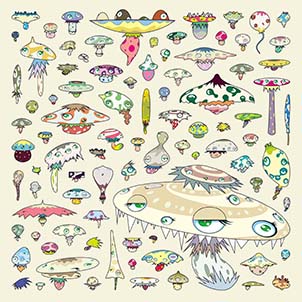

Taking a look at his iconography, we see that one of the most recurrent is fungi, perhaps atomic mushrooms? For those who think so, it might represent the trauma caused by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in WWII. For others, however, they symbolize male genitalia or a reference to drug-induced hallucinations.

Other motifs are his multicolored daisies with smiling faces and skulls which relate to the aesthetics of “kawaii” which means "cuteness" and which in Japan is used in situations that to Western eyes might seem incongruous. Is it also a critique of Japan's overly consumerist culture with a penchant for the childlike.

What is obvious is that his career has been unstoppable and that he has presented some very impactful exhibitions such as Coloriage (Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris, 2002) and Little Boy: The Art of Japan's Exploding Subcultures (Japan Society, New York, 2005).

After touring the MoCA in Los Angeles, the Brooklyn Museum in New York and the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt, he arrived at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao in 2009 with ©MURAKAMI, a retrospective displaying over 90 works of art in different mediums. For instance, there was the evolution over time of Mr. DOB and some of his other iconic characters, his figurative projects inspired by the “otaku” of the late 90s or fantastical sci-fi figures such as SMPKO2, among others. It is worth noting the presence of one of his most important pieces: Oval Buddha, silver (2008), which depicts a Buddha meditating on a lotus leaf. The exhibition rounds off with some abstract paintings all in different techniques (graffiti, Op Art or special effects), some of his animation work and, finally, a compilation of 500 items of merchandising manufactured by his company.

In 2011, following the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, he hosted “New Day: Artists for Japan”, an international charity auction at Christie's in New York. The Murakami-Ego exhibition, whose centrepiece was an astonishing 100-meter painting inspired by that same earthquake and the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster could be seen in 2012 at the Riwaq Al Hall in Doha, Qatar. In 2014, Takashi Murakami: Arhat Cycle was performed at the Palazzo Reale in Milan in 2014 and, at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow, which showcases the themes that the artist had developed in recent years about the origin of religions.

As a keen anime enthusiast, Murakami then moved onto action and set his characters in motion. He has made short videos, such as Pharrel Williams’ It Girl, but he has also undertaken major projects. Jellyfish Eyes is the first feature film in a trilogy that he directed and produced himself. It premiered in April 2013 at the County Museum of Art in Los Angeles and has been screened in museums and cinemas around the world. For 90 minutes, the artist takes us, through animation and real people, to the Japan that suffered the 2011 earthquake and the Fukushima disaster, unleashing the full array of colourful creatures to which we have grown accustomed. It was not easy for this project to come to fruition because of the artist's demands, as he himself acknowledges: "It's not a simple or a nice process. At the end of the first film, the team was so fed up they didn't want to work on the second."

The unusual thing about Murakami is his use of new technology: every creation begins as a sketch in one of his many pocket notepads. These drawings are scanned and from there, reworked in Adobe Illustrator, the composition retouched and thousands of colours played around with until the final version is delivered to his assistants who print them onto paper, silkscreen the outlines onto canvas and only then does the painting begin. He himself acknowledges: "Without the support of technology, I could never have produced such a large number of works efficiently and the work wouldn’t have been so intense."

Through his work, Murakami plays with contrasts and double meanings: East and West, past and present, high and low culture, sweetness and perversion, humour and social critique ... while still being consistently fun and accessible. According to him, an artist is someone who understands the boundaries between different worlds and makes an effort to familiarise themself with them.

His art, which at first glance could be dismissed as naive or superficial, is actually a complex art project which one discovers, on closer inspection, to be thoughtful and stimulating. The artist does not want to confine himself to just copying Western culture and behind each choice of his seemingly innocent figurines lies a social critique denouncing consumerism and the lack of cultural structures in Japan. He has said: "I express despair. If my art seems positive and cheerful, I doubt it would be accepted onto the contemporary art scene. My art is not pop art. It is a recognition of the struggle of people suffering discrimination."

"I’m surprised at the impact this exhibition has had." These are the words of Michael Darling, curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and regarding the artist himself, he says: "Superflat also alludes to the leveling of distinctions between high and low. Murakami likes to brag that he can make a million-dollar sculpture and then take the same theme and produce a load of cheap rubbish."

Despite some opinions railing against commercialization in his art, Murakami's commitment to achieving whatever he sets out to is undeniable and that has earned him a place among the most celebrated and in-demand artists of today.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Takashi Murakami: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

The former vice president of the US government under Bill Clinton's administration, Al Gore (Washington D.C., 1948), is known worldwide for his efforts in the fight against human-caused global warming. In 2007 he received the Nobel Peace Prize as well as an Oscar for Best Documentary (2007) for the broadcasting of his speech "An Inconvenient Truth". Concern for global warming was something that had haunted him since his time as a congressman in 1976. As early as 1998, he had already proposed the launch of the Nasa DSCOVR satellite which became possible, years later, thanks to his efforts.

Author: Elena Cué

The former vice president of the US government under Bill Clinton's administration, Al Gore (Washington D.C., 1948), is known worldwide for his efforts in the fight against human-caused global warming. In 2007 he received the Nobel Peace Prize as well as an Oscar for Best Documentary (2007) for the broadcasting of his speech "An Inconvenient Truth". Concern for global warming was something that had haunted him since his time as a congressman in 1976. As early as 1998, he had already proposed the launch of the Nasa DSCOVR satellite which became possible, years later, thanks to his efforts. Although he beat George W. Bush in popular votes, he lost the 2000 presidential election he ran for as the Democratic Party's candidate. Al Gore, Prince of Asturias Award (2007), is also the political father of the Internet. In 1978 he coined the term "Information Superhighway" and in 1991, as vice president in the Clinton administration, he created the National Information Infrastructure (NII) on which the Internet was developed. Gore is a visionary who knew how to solve the human need for interconnection. Once this challenge was overcome, he migrated from technological activism to environmental activism, from human interconnection to the survival of our planet.

You have experience advocating against climate change both in government and now in your foundation "The Climate Reality Project". In your opinion, where is your work most effective?

There is no position with as much influence as the position of president. That said, when I was not able to become president, I felt grateful to have the opportunity to influence in other ways. Ultimately, the solutions to the climate crisis must come from changed government policies. That would be the most influential way to go about it. However, in order to persuade governments to change, there is a place for advocates in the private sector and I am happy to be able to advocate for the right solutions.

If you were currently in government, what steps would you take in your country to help reverse climate change?

Number one, I would eliminate all government subsidies for fossil fuels. Number two, I would put a price on carbon, which would require action by the congress as well, but I believe it is now time to test the support for that measure, because I think it is there. Number three, I would accelerate the phase out of internal combustion vehicles such as cars and trucks and replace them with electric vehicles. Next, I would encourage regenerative agriculture to sequester more carbon in the top soil and plant as many trees as possible. Finally, I would launch a major program to make all buildings and factories much more efficient, with better insulation, windows, lighting and much higher levels of efficiency.

The United States is currently the second biggest polluter after China.

Yes. China is first and the US is second.

More than 90 percent of scientists consider that the greenhouse effect is anthropogenic. What would your strongest argument be to convince those who deny climate change exists?

First of all, it is now 99% of scientists. It is also Mother Nature itself whose arguments come in the form of hurricanes, floods, draughts and other consequences of the climate crisis which makes what scientists have been telling us for decades simply indisputable. If they are still deniers after all this time, I don’t know what might convince them. There are still people who believe the landing on the moon was a hoax. There are still people who believe that the Earth is flat. It is pointless to waste time arguing with such people.

How do the interests of dirty-energy (fossil fuel energy) companies affect the solution of the problem?

Some of the fossil fuel energy companies, especially in the US, have been using unethical strategies to slow down the solutions to the climate crisis. They have been doing the same thing that tobacco companies have been doing for so many years: putting information out to the public that is false and inaccurate. Tobacco companies hired actors, dressed them up as doctors and put them on television to lie to the public and tell them there were no health problems with cigarettes. Some of the fossil fuel companies, especially in my country, have been doing the same thing. They spend a lot of money to give the public misleading and false information about the climate crisis. They tell people that it does not exist, that it is exaggerated, that it is not a serious problem. President Trump is one of the biggest violators. He is supported by these fossil fuels companies precisely because he is willing to lie to people about the climate crisis.

What does it mean to you to receive the Nobel Peace Prize (2007) for your activism in favor of the theory of Climate Change?

The most important meaning is that it gives me a better opportunity to convince people that we have to change. It was the greatest honor of my life, along with the Prince of Asturias award. Both of these prestigious awards are important to me, not for personal pride, but because it gives me a better chance to gain an audience.

What are the main contributions of the COP25 World Climate Summit in Madrid? Have there been any significant advances?

Not yet, but usually the advances come on the final day of such conferences so I am hopeful they will break the impasse that currently exists at the conference center, where I spoke this morning. I hope they will be able to prepare the blueprint for next year’s meeting in Glasgow where all 195 nations will be asked to make bolder commitments to reduce their global warming pollution.

Does reaching an agreement between nations signify success even if not all countries are committed to it?

When the entire world reaches an agreement, that agreement inevitably puts a lot of pressure on all nations to do their absolute best to comply. It also puts a lot of pressure on private businesses, banks and investors. In some ways, business leaders are making more progress than political leaders. The reason for this is that the customers of these very businesses are telling them that they want to do business with companies that are part of the effort to solve the climate crisis.

Your documentary "An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power" covers the dilemma presented by countries like India, that need to burn fossil fuels in order to generate the energy needed to develop its industry, infrastructure and to increase the well-being of its population. As a solution, you advised them to increase their investment in renewable energies. Has there been any progress since the Paris Summit?

Yes, there has been fantastic progress in India. The country has experienced a big change since the Paris conference. They have started building massive solar and wind farms. Their electricity prices are going down. The air is no longer as dirty because of burning coal although they have other sources of dirty air that they still have a real problem dealing with. However, their commitment to solar energy is helping them build a better future.

In a climate emergency situation, like the one we are in at the moment, what impact do the Amazon wildfires have?

The new president of Brazil, Balsanaro, is responsible for no longer enforcing the environmental protections that have limited the burning of the Amazon. He is giving a green light and it has resulted in a much more fires. The risk is that the Amazon will be picked apart and will lose its ecological integrity. Scientists are now very worried that it will flip into a different ecosystem. Instead of being a forest it may become a savanna. If that happens, it will no longer absorb as much CO2 so it will make the global problem worse.

As the Amazon belongs to Brazil, how can we balance taking care of the world’s lungs with the demands of a growing population that has its own needs?

Destroying the Amazon is not a solution to poverty. It is simply a mistake and an ecological travesty. One reason it is a mistake is that the soil in the Amazon is extremely thin and it will not support agriculture for long. What we are seeing is a lot of corruption with people destroying the Amazon, making a quick profit and then abandoning it soon after. The way to create prosperity and more jobs is to accelerate the shift to solar and wind energy and sustainability as a blueprint. That can actually create more jobs and more wealth in Brazil than could ever be done by simply burning down the rainforest. In addition, it is important to remember that in the twenty-first century one of the most valuable resources is the unique pull of generic information that is in the rainforest. Cures for cancer and other diseases are often found in the exotic forms of life that exist in more abundance in the Amazon than anywhere else on Earth. It is foolish to destroy all of this genetic knowledge without even cataloging it and trying to use this information for its great value in medicine and in the making of new materials.

The overall notion seems to be that the development of new technologies, such as solar and wind energy, is slowing down but your stance is different to that. Could you explain why you are optimistic about it?

Many people are surprised when they see the latest business statistics. Electricity from the sun is now the cheapest source of electricity. The second cheapest source is electricity from wind. It is actually not that uncommon for people to be surprised when a brand new technology develops quickly. It is now a repeated pattern in the modern world where all of a sudden our mobile phones, for example, become supercomputers. They become everything; they can even act as flashlights. You can pay your bills with them. There are many other examples of these new technologies that at first are expensive and awkward but then they go down in cost and become much more sophisticated. This is what has happened with solar and wind energy. Those who have not been a part of that industry, after a few years pass, they see the new reforms and are very surprised but the business people who keep track of this are not surprised. They have been expecting this and they have been investing in it. Now, these new forms of energy are radically changing the energy marketplace worldwide.

The technology for storing solar energy has also advanced.

That is exactly right. In addition to the fantastic improvements in the technology for solar and wind, there is now also a fantastic improvement in the technology of batteries that can store the electricity so that you can use solar energy at night and wind energy when the wind is not blowing. The cost of these batteries has also been going down very rapidly.

And how about here in Spain?

There is less use of batteries in Spain than in most other advanced countries. I am not quite sure why that is the case but I think that will soon change. By the way, Spain has one of the most fantastic resources for solar energy than any other nation in the world. Particularly in the southern half of Spain. The development of batteries along with solar energy can transform the energy markets in Spain and sharply reduce the price of electricity making all businesses in Spain more competitive.

Regarding radioactive materials, do you think the nuclear waste management can be done in a safe manner?

Yes, I do, but nuclear energy, in its present form, is the most expensive source of electricity that we have. It is being phased out in most countries. China is still building a few new reactors but most countries are not, mainly because it is so expensive. There are two other problems. The handling of nuclear waste can probably be done safely but it also adds to the cost. Utility companies are paying money into a fund that is supposed to be used for the careful storage for nuclear waste but it is going to require even more money if there are more reactors built. Another problem is that the experience and knowledge necessary to manage nuclear plants has been hollowed out. The graduate schools that train nuclear engineers have not been training many nuclear engineers because after Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi the acceptability of nuclear energy was damaged in the minds of the public. Germany, for example, cancelled its nuclear plan.

When Alliance 90 (The Greens) entered the German government, Germany reduced its nuclear plants by twenty percent but in return increased its fossil fuel production. Now Germany is one of the biggest polluters in Europe...

The answer is not to go from nuclear to coal and gas, but to go from nuclear to solar, wind and batteries.

Given the current climate change emergency and the fact that nuclear power plants do not polute the atmosphere, should we consider nuclear power as a temporary solution to the urgent need to reduce emissions?

Most of the business leaders in the utility industry have become discouraged about nuclear energy. If you are the CEO of a utility company making and selling electricity and you decided to build a new nuclear plant, you would consult your staff and ask questions. One of the questions you would ask is how much it would cost to build a new nuclear plant. The truth is there is not a single consulting engineer in Europe or North America who will give you an answer to that question. No one can tell you how much it will cost. A second question you might ask is how many years it would take before the nuclear plant is finished so you can start using it to make electricity. There too, no one can give you an answer to that question. It is discouraging if you do not know how much it would cost or how long it will take to build. The utility company’s CEO would say that he/she does not want something with that much cost, uncertainty and trouble. That is what has been happening and it is happening in Spain as well. You have some nuclear plants here that are 40 years old and they keep getting 5-year extensions. They actually do provide about 20% of your electricity. I could be wrong, but I think that is about right. They do play a valuable role but the future of nuclear power does not look very good unless innovators come up with a new kind of nuclear plant that is less expensive and safer to operate.

What is your opinion of the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg?

I think she is fantastic. I am a big supporter of Greta. I met her a year ago in Poland at the United Nations Climate Change Conference. I greatly admire her ability to speak truth to people in power. I think she is a remarkable young woman and I am her biggest fan.

Al Gore during his interview with Elena Cué

- Interview with Al Gore - - Alejandra de Argos -