- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

London's Tate Modern is currently hosting a visit from a very different Van Gogh. The exhibition comes courtesy of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and includes a painting that seemingly brings with it the air of a Soviet billboard, a kind of propaganda, a punishment, a coldness. It is a far cry from Van Gogh's most iconic sun-soaked canvasses - no lilies, no sunflowers in vases, no wheatfields.

|

Colaborating author: Marina Valcárcel

|

|

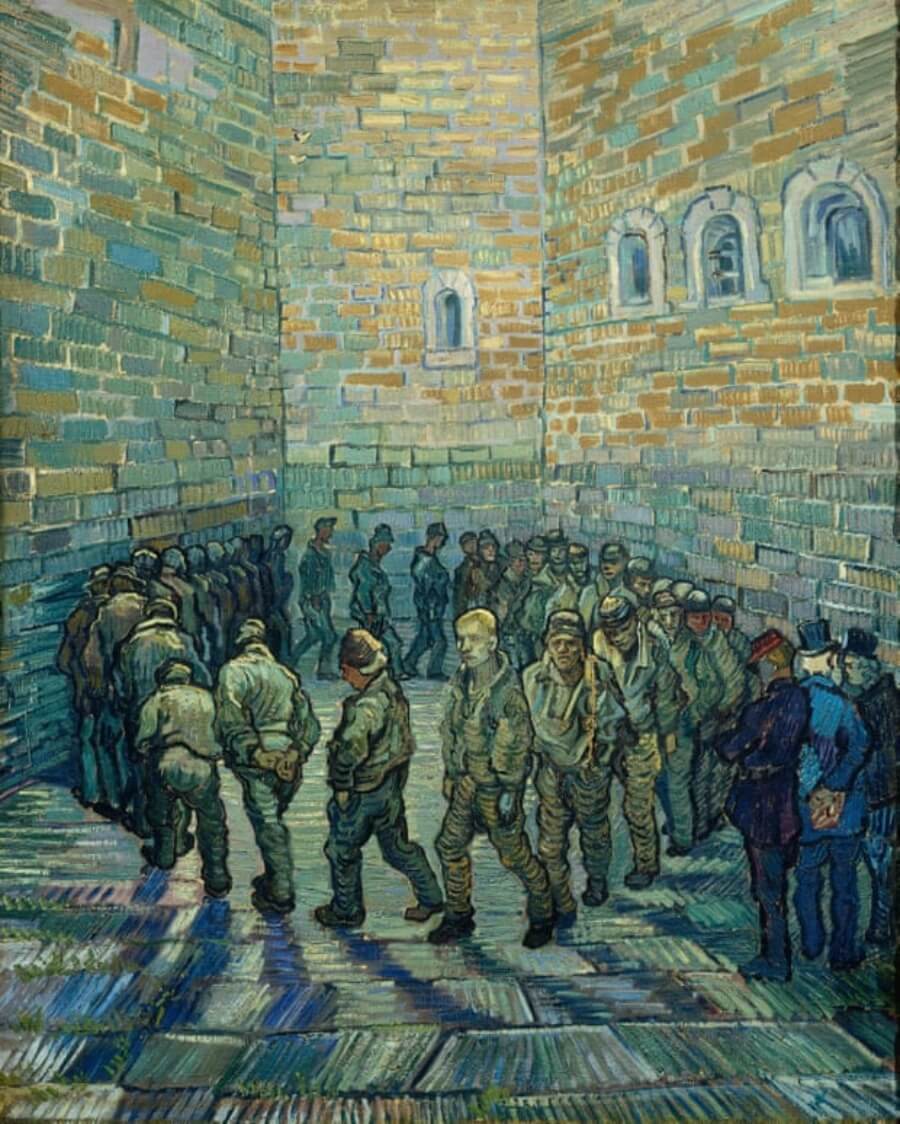

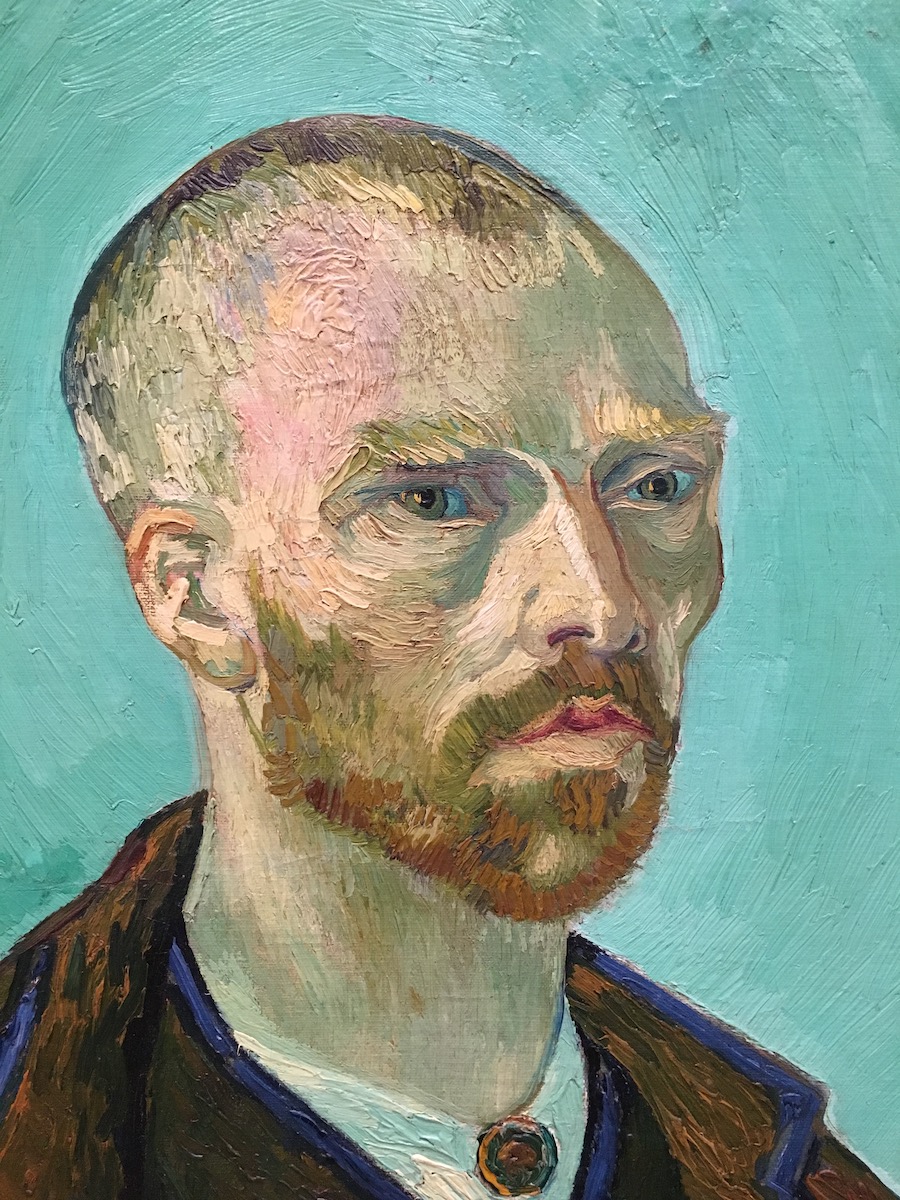

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-portrait dedicated to Gaugin (1888), Fogg Art Museum, USA

London's Tate Modern is currently hosting a visit from a very different Van Gogh. The exhibition comes courtesy of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and includes a painting that seemingly brings with it the air of a Soviet billboard, a kind of propaganda, a punishment, a coldness. It is a far cry from Van Gogh's most iconic sun-soaked canvasses - no lilies, no sunflowers in vases, no wheatfields. This is his most tragic painting and features a prison courtyard. Painted in February 1890, by which time Van Gogh was an inpatient at St Rémy asylum, rarely venturing outdoors to paint the countryside around him, instead feverishly reproducing the postcards his brother Theo sent him. This painting, based on an engraving by Gustave Doré, is a scream in the dark. It is his terror of madness and confinement. A group of 33 prisoners, heads down, drag their feet around a circle of oppressive and alienating exercise, enclosed inside a wall without end, two symbolic butterflies hiding between its bricks. A feeling of the absence of freedom permeates it. Only a small ray of light trickles down from an unseen sky to illuminate the face of one of the prisoners, the only one to lift his head and look at us. A blond-haired man, white-skinned. Vincent Van Gogh. On 27 July 1890, five months after completing this painting, he would go out into the wheatfields surrounding Auvers with a revolver and shoot a bullet into his stomach.

Vincent Van Gogh, Prison Courtyard (1890), Pushkin Museum, Moscow

A meditation on painting

Van Gogh died at the age of 37. Other visionaries who revolutionized the art of their time also died young - Basquiat at the age of 27, Egon Schiele 28, Modigliani 35, Raphael 36, Caravaggio 38 ...

Unlike them, however, Van Gogh's biography (1853–1890) stands out for something unusual - the bulk of his output came in the last two years of his life. Just over 700 days and 900 works that would blow the roof off Western painting. Two years in and out of hospital, devouring oil paint of the colour that obsessed him - yellow lead chromate. Making the most of any periods of calm for frantic painting, sometimes a picture a day, sometimes two, and battling the dazed stupor produced by the potassium bromide injected into his veins to prevent seizures. Painting so as not to go mad, painting every lily and every ear of wheat until his senses absorbed them, painting the sun and the moonlight, painting so as not to die, painting whilst dying.

In addition to his paintings, the Dutchman also left a key legacy - his correspondence, which has survived essentially intact to the present day. From August 1872 until his death, Van Gogh wrote over 800 letters, of which 668 were sent to Theo his younger brother, his confidant, accomplice, double. All of them begin "My dear Theo" and are written in Dutch, English or French.

This spring of 2019, all roads lead to Van Gogh: the Tate Modern has inaugurated its first exhibition dedicated to him since 1947 - Van Gogh in Britain - whilst the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is delighting visitors with a beautiful exhibition in which his landscapes dialogue with those of David Hockney. In Barcelona, there are long queues for the interactive Meet Van Gogh exhibition and Julian Schnabel's biopic - At Eternity's Gate - is still showing in cinemas.

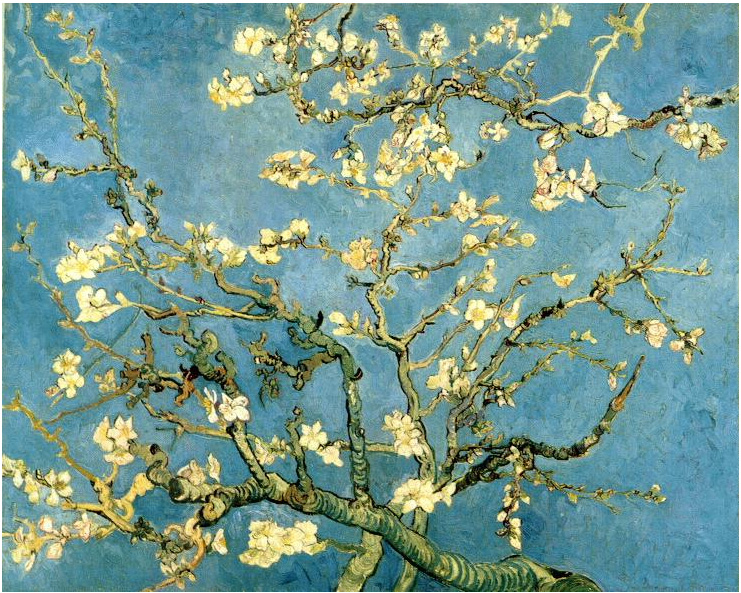

Vincent Van Gogh, Almond Blossoms (1890), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Holland

Long before Vincent picked a brush with the intention of learning to be a painter, he was already looking at the world through the eyes of an artist. As a child, he became practised at observing Nature during his long walks in the Brabant countryside: he examined birds' nests and wondered at the Dutch flatlands broken up only by the sharp spire of some church or by the red strip of sunset on the skyline.

Through his father, a Calvinist pastor from the Dutch town of Zundert, he was immersed in a traditional learning method then prevalent in northern Europe, namely, that everything we observe is full of metaphorical and symbolic meanings. Much of this teaching to children was done through the holy prints that surrounded them in their homes. In his father's studio hung three engravings that impacted Vincent as a child: The Return of the Prodigal Son, The Harvest and a baby in his cradle by Rembrandt; simple scenes that lit the flame of a profound religious sensitivity in Van Gogh from a very early age.

The search for salvation

Behind those blue eyes, Vincent's life revolved around the inner workings of his own mind. Long before art made its appearance, there was not only the need to seek his salvation but also a voracious amount of reading - the Bible first and foremost, along with Shakespeare, Dickens, Hugo, Homer and Balzac, to name but a few. Between the ages of 16 and 30, he and his brother Theo worked as assistants at the Goupil Art Gallery and travelled throughout Holland, London and Paris. It was in these cities that Van Gogh immersed himself in museums and galleries, deciphering the works of the painters he most admired: Rubens, Frans Hals, Delacroix and, of course, Rembrandt. In Paris, he encountered the Impressionists, Japanese prints with their bright colors and lack of perspective or shadow and the dotted brushstrokes of the Pointillists. And everything learnt from museums and books served to expand the treasure trove of images and memories he would carry with him like baggage.

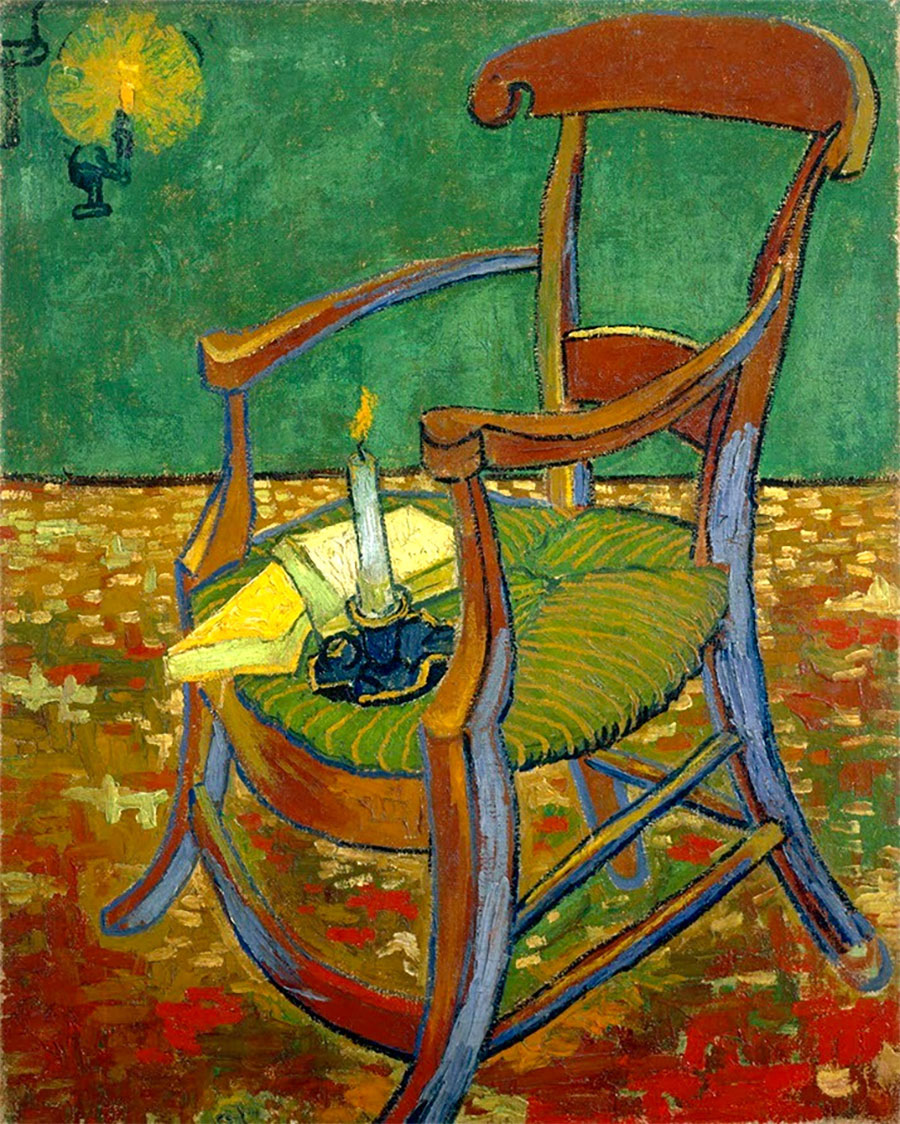

At 30 and in less than a decade, this fragile and confused young man decides to learn to paint, assimilating all contemporary innovation and emerging as the pioneer of the most modern, expressive forms of painting. And so, in February 1888, Vincent boards the train to Arles where his painting would reach maturity while his life begins to fall apart. Living in the Yellow House and obsessed with Gaugin's arrival, he churns out, at the rate of sometimes six canvasses a day, his legendary paintings: the Sunflowers series, A Pair of Boots, Gaugin's Chair, his Bedroom in Arles ... the same room where he would soon be found dying. In Van Gogh As Prometheus, Georges Bataille asserts that it is precisely on the night in December 1888 that he handed over his severed ear at a brothel "... [w]hen his painting turns into lightning, explosion and flame; while at the same time he himself disintegrated in ecstasy before a beam of radiant light, exploding, on fire."

Vincent Van Gogh, Gaugin's Chair (1888). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Holland

Dawn of the collapsible paint tube

In Provence, he embraced the landscape, turning its abundant indigenous bamboo and reeds into brushes and pencils. He was also able to benefit from advances in the chemical industry as new colours appeared in the form of coal tar pigments, mauve and magenta aniline dyes and synthetic lacquer tints. But, more importantly, came the invention of the squeezable paint tube, which made painting with oil outdoors possible for the first time.

When he took his easel out into the countryside, he would turn his head like sunflowers in search of sunlight and colours, sensing nature in all its glory: temperatures, sounds, mistrals, scents ... and then falling into a state of hypnosis. The last snows had just washed the fruit trees in the orchards clean. There were paths and yet more paths lined with trees of all kinds and everything was starting to shine with an intensity that Vincent painted in short, stenographic lines. It was then that he discovered the motivation for his painting: in nature he found the power of suggestion in the colours he used to convey poetic ideas and to express feelings or moods. In his film, Julian Schnabel enables us to experience Van Gogh's catharsis through optical illusions. He recounts how one day, in a second-hand shop, he came across a pair of bifocal glasses. While wearing them, he realized that his field of vision was altered, blurred or expanded and believed he had hit upon how to convey on screen the artist's trancelike way of seeing the world.

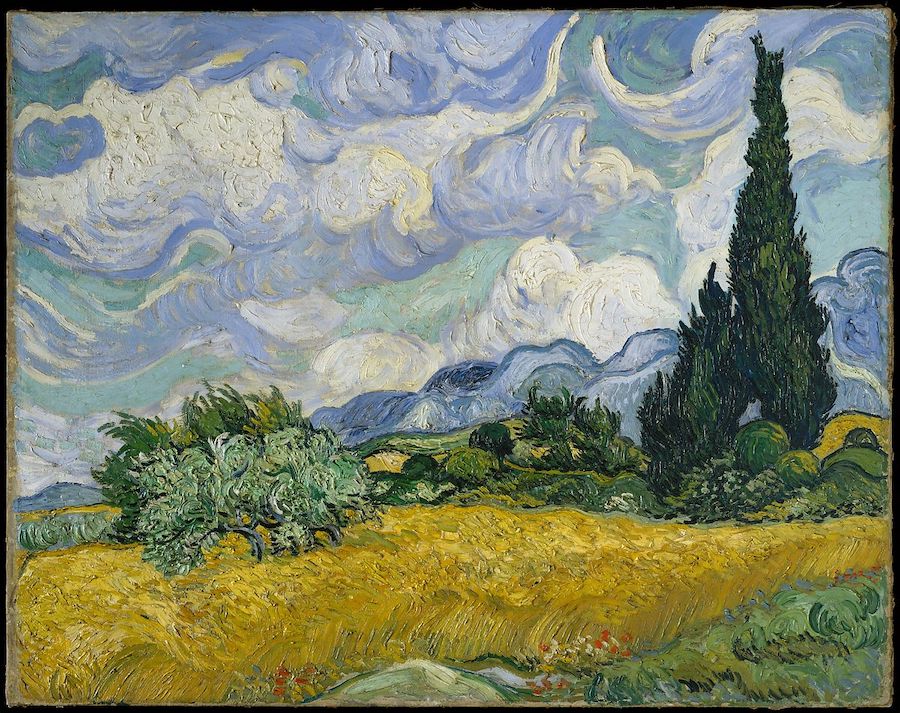

Vincent Van Gogh, A Wheatfield with Cypresses (1889). Metropolitan Museum, New York, USA

In Amsterdam recently, Hockney spoke with devotion: "I think my debt to Van Gogh is obvious here. For me, he's a contemporary artist. He still speaks to me today, like Brueghel." Van Gogh and Hockney lived a century apart but their landscapes, on display side by side, are like stars colliding: "Although it's obvious we both have a fascination with nature, what links me most to Van Gogh is not his colours, brushstrokes or landscapes, it's the clarity of his spaces." Insisting on their similarity of brushstroke, he replied with a smile: "Well, sometimes I steal things from Van Gogh. Great artists don't borrow, they steal." He added, seriously: "With a photograph, the whole surface is uniformly flat. Between a photo taken of a Van Gogh painting and the actual canvas, the difference is the brushstrokes. We can't look at a photo for long, no more than a fraction of a second, because we don't see the subject in layers. The portrait Lucian Freud painted of me required me to pose for 120 hours and that can all be seen in the layers of the painting. That's why it's of infinitely higher interest than a photo."

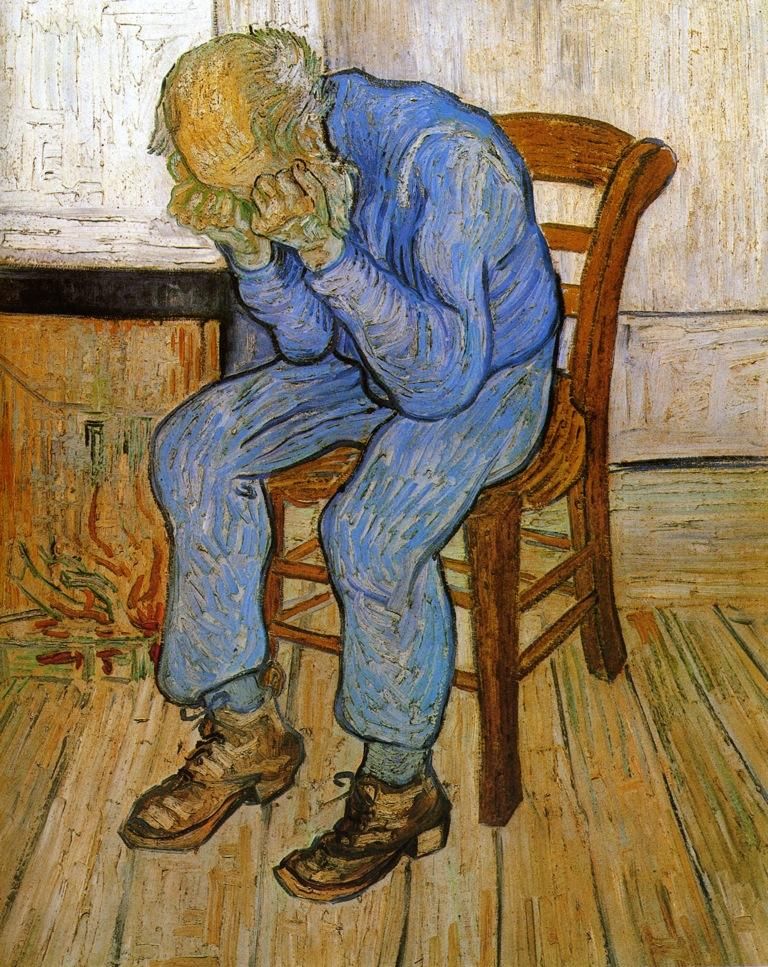

The London exhibition, the one in Amsterdam and Schnabel's film converge miraculously in one standout picture currently at the Tate Modern. It is At Eternity's Gate, the selfsame title as Schnabel's film. Along with The Prison Courtyard, Van Gogh painted it in April 1890 during his days of isolation at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum and this time it is based on a drawing of his from the Dutch period. It depicts a man sitting in a chair with his head buried in his hands. A symbol of despair and, more likely, of Van Gogh's own anguish. Two weeks before starting it, his doctor, Théophile Peyron, wrote to Theo: "He usually sits with his head in his hands and whenever someone comes to talk to him, it seems as if it causes him immense pain."

Conversely, for Hockney, At Eternity's Gate signifies a rebirth. In March 2013, one of his assistants, Dominique Elliot, committed suicide at the artist's house while he was painting the Yorkshire landscapes that are currently on display in Amsterdam. For several months, Hockney was unable to paint. In July of that same year, Hockney sent a drawing to his friend and curator Edith Devaney. It was a portrait of his friend Jean-Pierre Goncalves de Lima, sitting in his studio with his head in his hands. Devaney instantly spotted the similarities with Van Gogh's painting. Hockney acknowledged that this was not only a portrait of his friend but was also a kind of self-portrait in the face of tragedy. After that portrait came many more, which, in 2016, would become an exhibition at the Royal Academy: 82 Portraits and 1 Still Life. Van Gogh had persuaded Hockney to take up painting again.

Vincent Van Gogh, At Eternity’s Gate (1889). Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Holland

Silent contemplation

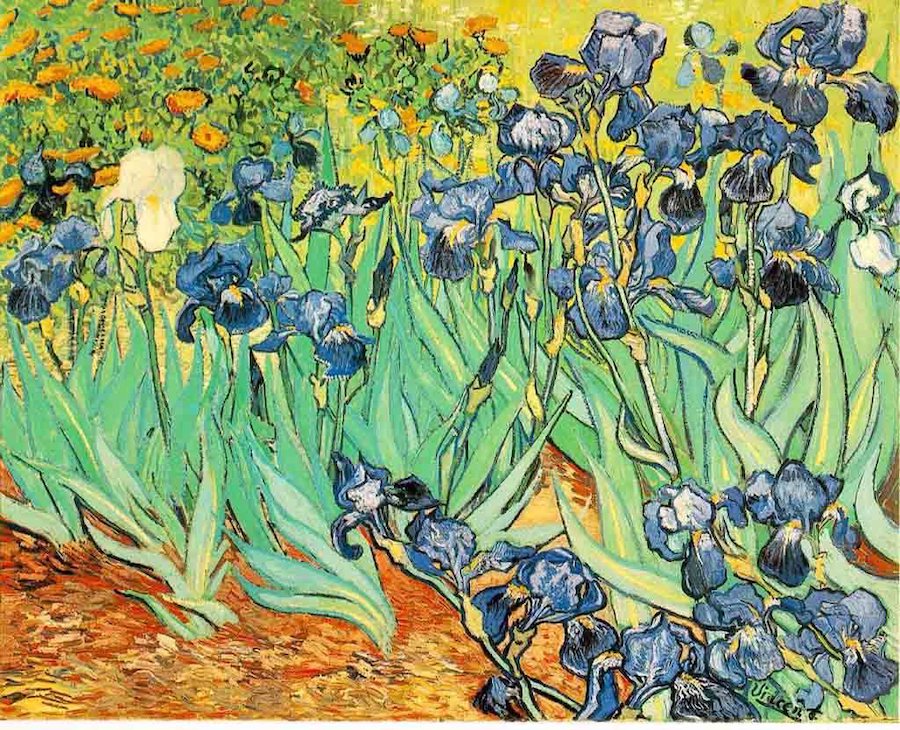

In 1890, during his confinement, Van Gogh found himself even more deeply affected by everything than before. He breathed every breath behind the bars and felt his spirit vibrate behind the window panes, letting it merge with the changing landscapes, light and seasons through his brushes. In the monastery's walled garden, he became a silent contemplator. Sitting under the trees, his eyes captured everything he saw. He would lie next to the lilies, face to face, and paint them, as if one of them, at one with them. When we look at his paintings today, we can almost feel the air, the freshness under the shade, the grass and lavender moving. Vincent wrote at the time that he was in his heaven.

Vincent Van Gogh, Irises (1889). J.Paul Getty Museum, California, USA

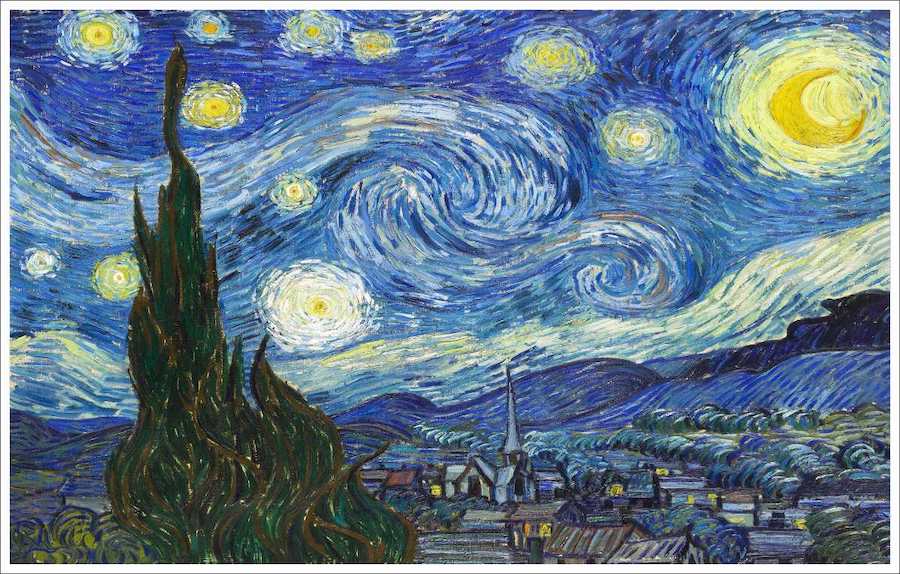

However, towards the end of his life, the struggle inside his head between art and madness took on heroic proportions. The recurrence of crises was terrifying. In moments of calm, he painted furiously as if trying to ward off the next attack that would inevitably come the following day. For Van Gogh at this time, painting was both his destruction and at the same time his salvation, because it was precisely between episodes that he could see with greater intensity and lucidity and when his pictorial faculties seemed to be totally under control. These were works of wild abandon, painted on the edge of the abyss. Over and again, he painted barley-sugar cypresses like Solomon's columns, wheatfields with never-ending paths, starry night skies speckled as if by glistening gas lamps, cloud chains moving like ship sails tossed by the wind.

Vincent Van Gogh, Starry Night (1889). MoMA, New York, USA

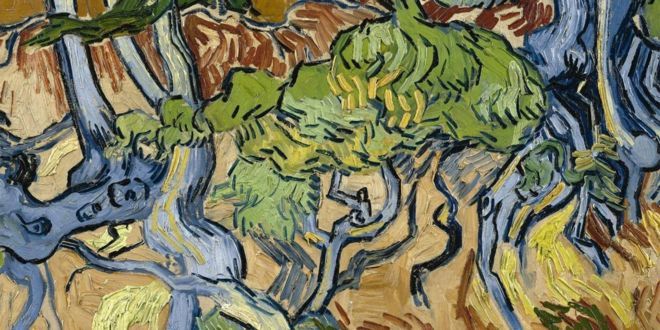

In May 1890, Theo knew that his brother was going through the most terrible time. He could see that Vincent was about to pull off a miracle and turn his mental disorder into a revolution. Theo feared that all of the internal intensity tormenting van Gogh was sure to explode inside his head once and for all. And he found a place for the explosion to be a controlled one - the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, 20 kilometres north of Paris. There, accompanied by Dr. Gachet, Van Gogh found the strength to unleash his final creative fury. Over the 70 days his spell in Auvers lasted, he produced 90 paintings. Many of them are his most exceptional works, almost always landscapes - solitary, disturbing and absolutely novel. His last painting, Three Roots, featured at the Amsterdam exhibition, is a manifesto to abstraction..

Vincent Van Gogh, Three Roots (1890). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Holland

In one of his last letters to Theo, Vincent lamented the fact that in the absence of any children of his own, his paintings would be his legacy. But Van Gogh did have a descendant - Expressionism. And along with it, many heirs - Kokoschka, De Kooning, Jackson Pollock ...

Within a few months, Theo, exhausted and ill, had lost his mind and also died. In 1914, his remains were moved to the cemetery in Auvers where he rests beside Vincent, with a matching headstone. From there, the two brothers observe Van Gogh's triumph - "Flowers die, mine will live on."

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

"Art has nothing to do with ugliness or sadness. Light is the life of all it touches; so the more light there is in a painting, the more life, the more truth, the more beauty it will have." It is no coincidence that Joaquín Sorolla is known as "the painter of light". The spectacular effects that the Valencian master imprinted on his canvases have yet to be matched by any other artist.

Life through light

Joaquín Sorolla photographed by Gertrude Käsebier, 1908

"Art has nothing to do with ugliness or sadness. Light is the life of all it touches; so the more light there is in a painting, the more life, the more truth, the more beauty it will have." It is no coincidence that Joaquín Sorolla is known as "the painter of light". The spectacular effects that the Valencian master imprinted on his canvases have yet to be matched by any other artist. The search for life through light was a constant in his work, often imbued with the brightness of the beaches and landscapes of his native Valencia. However, Sorolla's work is not limited to just seascapes, beaches or figures on the seashore. As a painter, he was also a magnificent portraitist and an exceptional portrayer of Costumbrista scenes.

The sheer magnitude of his output would be near impossible to equal, his works coming to almost three thousand paintings, in addition to the more than twenty thousand drawings and sketches he produced throughout his life. His prodigious visual memory enabled him to adopt one of impressionism's remits: that of capturing ephemeral moments or incidents and turning them into works of art. Sorolla was able to remember the light and movement of a scene from a single moment and then capture that scene in his studio. Today, Sorolla's paintings embody and convey the full light of the Mediterranean in each brushstroke and, due to their impressive, innovative qualities, they enjoy a special place in the most important museum collections and art galleries in the world.

Painting, an innate vocation

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida was born in Valencia in 1863. At the tender age of two years old, the future artist and his sister Eugenia lost their parents to the cholera epidemic sweeping the city. The two orphans were taken in by an aunt and uncle, who assumed responsibility for their education and upbringing. From his earliest years, Joaquin demonstrated an innate passion for art, drawing and painting. His locksmith uncle tried to steer him towards his own trade, to no avail. It was the headmaster at his secondary school who realized how gifted he was and suggested he train at the School of Craftsmen of Valencia. Sorolla enrolled at the age of 13 and two years later moved up to the High School of Fine Arts in Valencia where he was already proving to have extraordinary skills in brushwork and the rendering of realistic images, heavily influenced by Valencian seascape painters such as Rafael Monleón y Torres, among others.

Seascape (1880)

After finishing his studies, Sorolla meets the painter Ignacio Pinazo who introduces him to brand a new way of treating light in painting, a recent trend he had discovered on a trip to Italy. It is the young artist's first contact with Impressionism and, for the rest of his life, his work will adhere to many of its tenets. The fundamentals of this school are already reflected in his first seascapes, three of which he will send to Madrid for participation in the 1881 National Exhibition of Fine Arts. It is around this time that Sorolla met the photographer Antonio García, who would offer him work in his photography studio and whose daughter, Clotilde García, he would end up marrying.

“To get famous, you have to paint dead people"

The Cry of the Palleter (1884)

The stringent artistic constraints of late 19th century Valencia did not lend themselves to the restless spirit of the young painter, who nevertheless adapted to its demands in order to succeed. In 1884, the Provincial Council of Valencia convened a painting competition with the winning entry to be awarded a scholarship to complete their studies in Rome. The theme was the 1808 War of Independence. Sorolla submitted his work "The Cry of the Palleter" which made such a deep impression on the jury, they granted him the scholarship. Sorolla accepted the prize with skepticism and irony, confessing to a friend and colleague: "Here, to get famous and win medals, you have to paint dead people."

During this stay in Rome, Sorolla discovers the work of the great Italian Renaissance painters but his admiration is not limited to the classical as he also comes into contact with the work of Mariano Fortuny, whose canvases exert a powerful influence on his future work. This influence is clear in paintings such as "Moor with oranges" in 1887. From Italy, he travels to Paris where he acquires a new social conscience that will see itself reflected in many of his future works. In his early Italian period, he developed the long, powerful brushstroke that would characterize his work in the ensuing years. The presence of light will continue to gain importance in his canvases although this earned him serious criticism in Spain, where it still took precedence over technique and innovation.

Light and social realism. In search of his own style

Another Margarete (1892)

By 1889, Sorolla had completed his scholarship and learning period and, accompanied by his now wife Clotilde García del Castillo, returned to Spain where he began a time of consolidation, continuing to search for his own style, which was now beginning to appear in his work. His painting combined passion for the portrayal of an instant in time and light, characteristic of Impressionism, with personal touches (such as long brushstrokes or the use of earthy and black tones). Sorolla also opted to portray topics of a social and realistic nature, which also distanced him from the Impressionism that was triumphing throughout the rest of Europe. A good example is "Another Margarete" (1892), a work depicting an inmate being taken to prison in a train wagon after murdering her son. The title refers to the character of Margarete, one of the protagonists of Goethe's play "Faust". The oppressive and dramatic atmosphere of the canvas is accentuated by the use of light and the depiction of the characters' expressions. It won first prize at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1892.

Return Of The Fishing Boat (1894)

In the ensuing years, Sorolla continued to gain recognition, with works such as "And they still say fish is expensive!" and "Return Of The Fishing Boat", both painted in 1894. This latter work in particular marked the moment when he finally hit upon a way to depict light that he had been seeking from the very beginning and which he would adopt in his future works. During these years, he achieved widespread success and popularity, the painting being acquired by the French Government and also winning the Second Place Medal at the Paris Salon in 1895.

On the beach. Brushstrokes and seascapes

Evening sun (1903)

On the advice of his friend Aureliano Beruete, Sorolla then began working as a portrait artist. He went on to achieve considerable success, painting some of the most important figures in the social, intellectual and political spheres of the day. At the same time, he and his family spent three summers in Jávea, where he painted numerous landscapes, seascapes and beach scenes. The presence of bathers, swimmers, children on the shore and fishing boats became a constant, giving rise to works such as "Evening Sun", from 1903 (considered by Sorolla himself as his best painting).

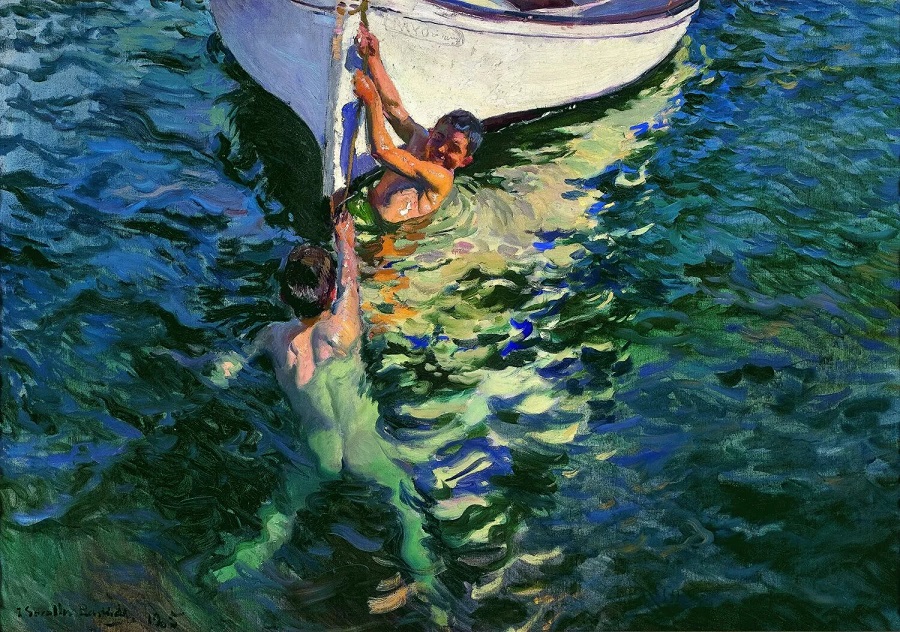

The White Boat (1905)

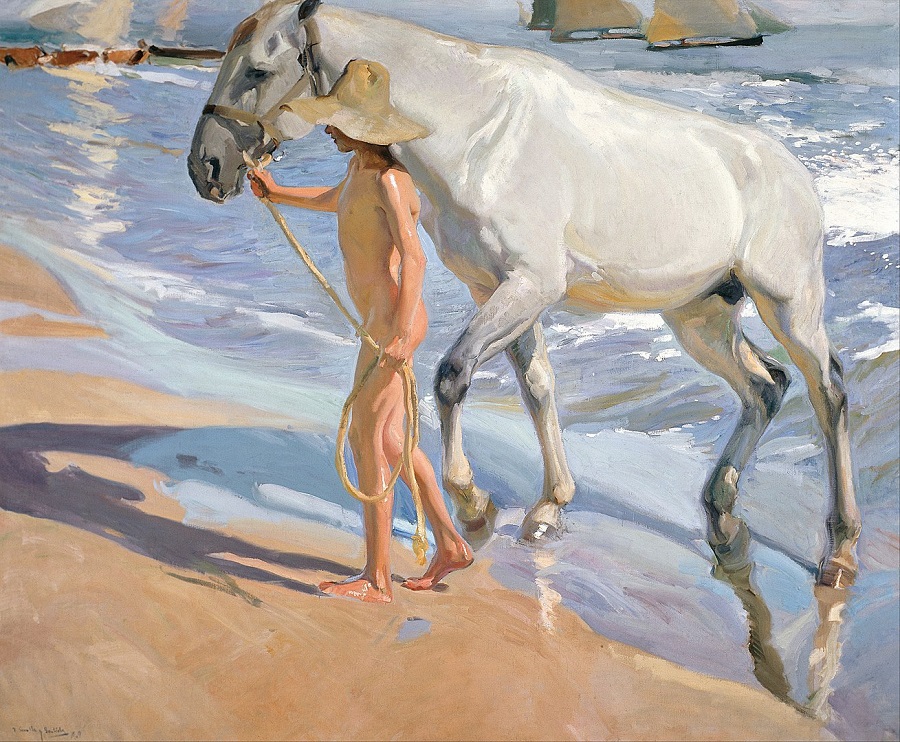

Sorolla's treatment of light, framing and colour in these paintings is masterful and as personal as it is unique. On the one hand, his work is very much in the vein of Impressionism but, at the same time, breaks away from it, through long brushstrokes and his colour palette. In 1905, he painted one of his masterpieces, "The White Boat", followed by even more famous and lauded paintings such as "Children at the Beach", "A Horse Bathing" or "Seaside Stroll" (all painted in 1909).

A Horse Bathing (1909)

The Hispanic Society panels: the work of a lifetime

The Sorolla Gallery (north wall), Hispanic Society of America

1911 was a momentous year for Sorolla. The Hispanic Society of New York commissioned him to paint fourteen panels to decorate the library at its headquarters, an enormous task he undertook with enthusiasm, producing a series of paintings depicting scenes from different Spanish regions. Sorolla would define it as his "lifetime's work" and dedicate his final years to its completion. He was then living and working in Huelva from where, in 1919, he sent a telegram to his family announcing he had finished the last painting. The following year, he suffered a stroke that left him unable to travel to New York where he had planned to deliver, assemble and attend the inauguration of his work. The commission would thereby remain unresolved and the contract unsettled until after Sorolla's death in 1923 on the reading of his will.

Sorolla Gallery (detail), Hispanic Society of America

In 1926, the gallery was finally inaugurated, bringing to a close a work that perfectly sums up Sorolla's style and technique. Although for a large part of the twentieth century, the advent of avant-garde and new pictorial schools forced Sorolla's work into the background, the latter decades saw a renewed interest in his paintings which, from then on, were to sell for astronomical prices and become much sought-after by museums and private collectors alike. Today, Sorolla is considered one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century and the most skillful at capturing the light of the Mediterranean on canvas.

Exhibitions

Joaquín Sorolla. 1863-1923 (2009)

In 2009, the Prado Museum organized its first retrospective of Sorolla's work. The exhibition was at that time the largest ever held to date, either in Spain or abroad, and brought together more than a hundred paintings. For the occasion, the Prado was loaned all fourteen of the panels that Sorolla painted as a commission for the library of the Hispanic Society of New York.

Sorolla: A Garden To Paint. Bancaja Foundation Valencia (2017)

A total of 120 paintings were selected for this exhibition in his hometown, organized by the Bancaja Foundation. Away from the classic seascapes and beach scenes that make up his best-known works, the exhibition focused on his passion for gardens and his depiction of them in paint. According to Sorolla, these places contained the "emotional parameters" so sought after by himself and other avant-garde painters.

Sorolla and Fashion. Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and Sorolla Museum (2018)

In collaboration with Madrid's Sorolla Museum, the Thyssen-Bornemisza offered here an unprecedented and novel point of view. The paintings selected for the exhibition analyze the influence of fashion and clothing trends on Sorolla's painting. Seventy works, some of them never before exhibited, were displayed alongside outfits, accessories and garments of the period. Sorolla's canvases are a magnificent chronicle of the trends and fashion of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, painted with the mastery and freedom of technique that characterize his work.

Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light. National Gallery, London (2019)

This retrospective by one of the most important museums in the world was one of the largest exhibitions of the Valencian painter's work ever organised outside Spain. For the occasion, London's National Gallery selected sixty masterpieces that cover the painter's entire trajectory from genre scenes of Spanish life to seascapes, beach scenes, portraits and garden views.

Books

“Eight essays on Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida”. VV.AA. (Nobel)

Successful republication of 'Eight essays on Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida', first published in 1909 on the occasion of the exhibition held that year at the headquarters of the Hispanic Society of America (New York). The exhibition welcomed some 170,000 visitors, which led to the publication of the texts in response to its resounding success. According to Blanca Pons-Sorolla, great-granddaughter and Sorolla expert, it is one of the most important books about her great-grandfather, that deserves to be "in every important museum and library in the world".

“Sorolla. Masterpieces”. Blanca Pons Sorolla. (El Viso)

The aim of this splendid compilation is to become the definitive publication about Joaquín Sorolla and his painting. The book uses high-resolution photographs of the artist's best works, including those that have been restored in recent years. Blanca Pons-Sorolla has personally ensured that the images remain as faithful to the originals as possible, as well as being responsible for the selection and writing of the accompanying texts.

“The Collected Letters of Joaquín Sorolla”. (Anthropos Barcelona)

This book includes the five hundred letters that Joaquín Sorolla exchanged with his friend Pedro Gil Moreno de Mora, who he met in Rome in 1885 during his stay and scholarship there. Although they rarely met up in person, they both kept up the friendship over decades through their correspondence. The letters are documentation of great historical relevance, revealing the intimate personality of the painter as well as his pictorial and artistic concerns.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Joaquín Sorolla: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

Tamara de Lempicka never gave up her independence and freedom. She maintained both thanks to her inate talent for painting, which gave her fame and fortune during her time. Nowadays she is considered the Queen of Art Déco, and her paintings are included in the best public and private colections of the world.

An artist in constant self-reinvention

Tamara de Lempicka painting “Suzanne Bathing” (1938)

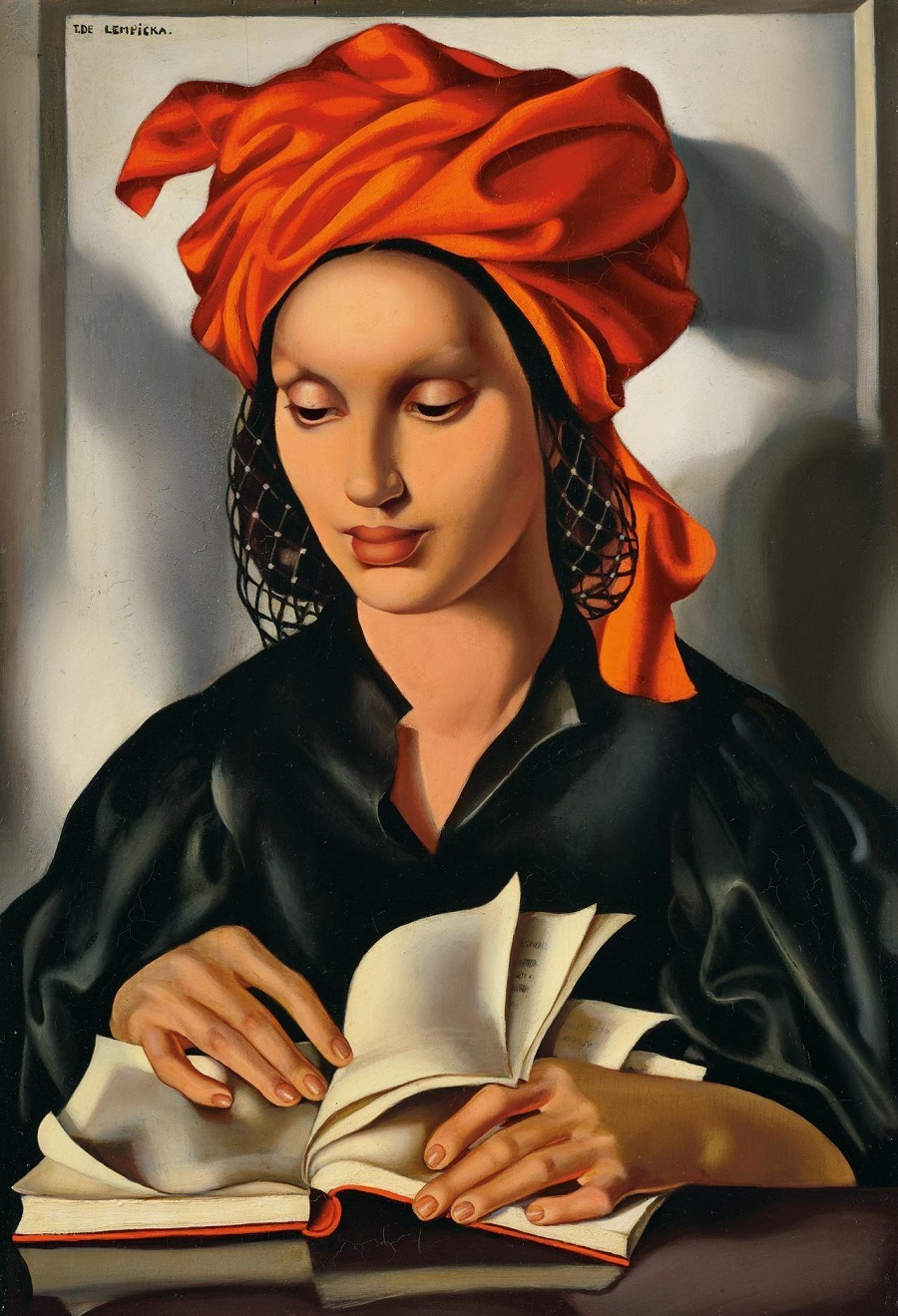

Tamara de Lempicka was not always acclaimed as an artist. At various times in her life, she enjoyed huge recognition and was, in fact, one of the few women who managed to earn a living as an artist. But in her later years, during the heyday of American abstract expressionism when anything remotely resembling the figurative was shunned, her work lost critical acclaim and even interest. In recent decades, however, de Lempicka's work has been rediscovered and reappraised, and although she figures today as one of the most sought-after artists of the 20th century, her life and character are still somewhat of a mystery - her inherent mythomania having driven her to invent her own narrative in which reality coexisted with pure fabrication.

What we do know to be true, however, is the power, solidity and innovation her paintings brought to the art scene in the first half of the 20th century. In particular, her portraits and female nudes have become the iconographic paradigm of the Art Deco movement, being very much in demand by celebrities and collectors alike. De Lempicka was very clear about who she was and, above all else, who she aspired to be. "I was the first woman to paint pictures that were neat, precise and finished and that was the secret to their success. Out of a hundred paintings, it was always possible to recognise mine. And the galleries tended to centre me in their best rooms because my art was attractive to the public." - something that remains true today with de Lempicka's work attracting thousands of visitors to museums and exhibitions for their remarkable modernity, harmony and timeless qualities.

Childhood in Russia and first contact with classicism

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact date of de Lempicka's birth. Her penchant for reinventing her own story meant she blurred biographical data to such an extent that even the experts are confused. However, many biographers are agreed that she was born in Warsaw in 1898 while, according to the artist, she was born in Moscow in 1907. What is unequivocal, though, is that her father, a well-to-do Russian lawyer, moved the family to St. Petersburg when she was still a child.

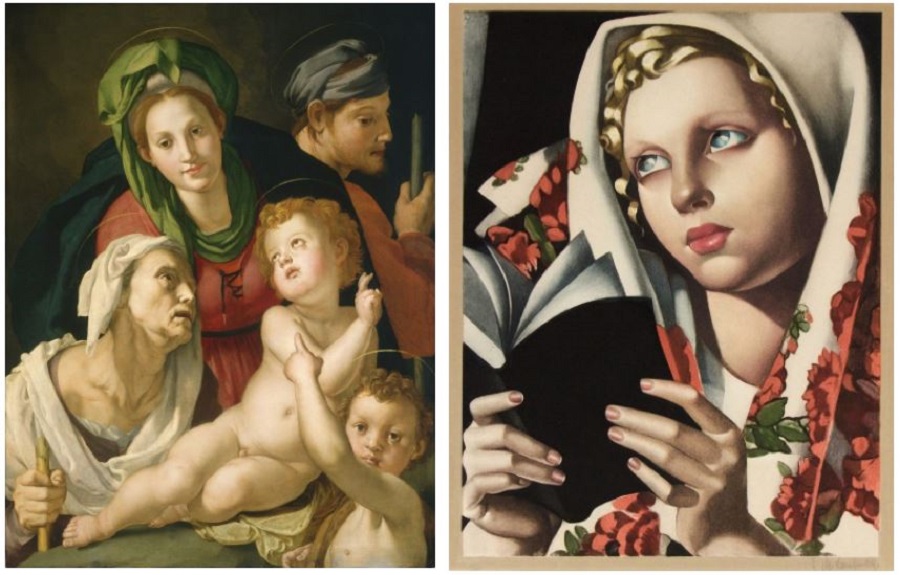

The Holy Family (1527-1528), Agnolo Bronzino. The Polish Girl (1933),Tamara de Lempicka

During her childhood, de Lempicka's first contact with art had a deep impact on the budding painter's impressionable young personality. Her aristocratic grandmother took her on a trip around Italy in 1911 when she was just 13 and which she later described as: "Suddenly, I came across works painted in the 15th century by Italian artists. Why did I like them so much? Because they were so clear, so sharp ..." The clean lines and saturated surfaces characteristic of Italian Mannerists were to exert a powerful influence on her art, an influence that would last for the rest of her life.

Escape to Paris and years of artistic training

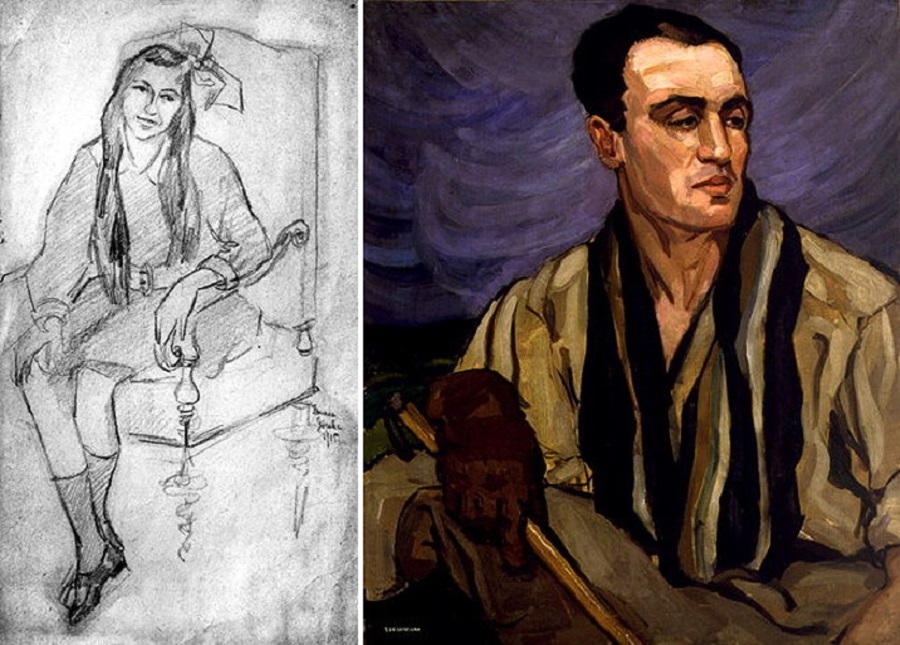

“Portrait of Irena Kleinman” (1915) and “Portrait of a Polo Player” (1922)

Despite her obvious passion for art, the future artist did not take up painting during her teenage years. As was usual at the time and in the wealthy social class to which she belonged, at just 18 she married the Russian lawyer Tadeusz Lempicki and had a daughter, Kizette. It is a year of luxury and glamour and the couple are the toast of society salons and dinner parties just before the eruption of the Russian Revolution in 1917. And then things change radically: Lempicki is imprisoned and only freed thanks to the perseverance of his young wife, who leaps into action and appeals time and again, office by office, for his release. The Lempicki family flees to Denmark and then to Paris, where they are forced to confront a new adversary in the form of financial hardship and a lack of the luxuries to which they had been accustomed. Her sister Adrienne, who lived in Paris at the time and was fully integrated into the modernity of the city (which advocated for the liberation of women and their equality with men in terms of rights and obligations), gives her the best advice of her life: "get a career and you won't have to depend on your husband."

In later life, de Lempicka would define herself on various occasions as a self-taught artist. During her early adulthood, however, she studied at several Parisian institutions, from the Académie de la Grande Chaumiére (where she trained under the Symbolist painter Maurice Denis) to the Académie Ranson, founded by the Fauvist Paul Ranson. She also spent whole days at a time in the Louvre, soaking up the work of the masters. But, without a doubt, her greatest mentor was the fauvist André Llhote, from whom she absorbed and internalized the ability to capture solidity and volume in forms, while applying some of the fundamentals of Cubism (especially the fracturing of perspectives and the distortion of shape).

On society's margins: the 1920s

“The Kiss” (1922)

"I live life on the margins of society, and the rules of normal society don't apply to those who live on the fringe." de Lempicka once said. She always considered herself an exceptional, privileged person and took pains to create and maintain a close relationship with the highest aristocratic circles and uppermost echelons of the avant-garde of her time. It was in 1922 that she added the "de" (of) to her surname and began modifying and creating her new biography. De Lempicka was a regular at literary salons where cocaine, hashish and alcohol flowed freely and, as Jean Cocteau once commented, she adored "art and high society in equal measure". Her bisexuality, widely tolerated by the circles she moved in, is faithfully reflected in many of her works. The artist's paintings leave no doubt as to their celebration of the female body in all its potency and solidity, and in their depictions of love and sexual attraction between women.

“La Belle Rafaela” (1927)

Works such as "Group of Four Nudes" (1925) or "La belle Rafaela" (1927) show tightly-cropped areas totally occupied by close-ups of naked female bodies in openly sexual positions and with the flat, geometric and sharply outlined style that have made de Lempicka's work the paradigm of Art Deco. The influence of 19th century masters is evident in these works and clearly linked to the paintings of Ingres and Manet. Like the latter's "Olympia", Rafaela was a prostitute from Marseille (and also one of her lovers) but, unlike the woman portrayed by Manet, de Lempicka's Rafaela is virile, voluptuous and totally indifferent to 'the male gaze' and male judgment. Also around this time, she paint the portraits of many aristocratic figures, thanks to the sale of which she was able to maintain her high standard of living.

Success, separation and war: getaway to the U.S.A.

“Self-portrait in a green Bugatti” (1929)

In the 1920s, de Lempicka became the darling of the aristocratic, high society set but it was in the late 1920s and early 1930s that her success reached its height. In 1929, she painted one of her most famous works, "Self-Portrait in a Green Bugatti", that would become the most famous and recognizable icon of Art Deco painting. On the canvas, the subject looks defiantly at the camera and paints herself in the driving seat usually occupied by men. It was commissioned for the front cover of the German fashion magazine Die Dame (The Lady) and is a compendium of the artist's unique and personal style: fully covered surface, geometric and outlined areas, metallic reflections that make it almost impossible to distinguish between metal and fabrics, and a blatant challenge to 'the male gaze'. This period of success is followed by a dark time for de Lempicka: that same year she divorced her husband and, in 1933, her commissions began to dry up due to the economic crisis occasioned by the Great Depression.

"Wisdom" (1940-41)

In 1939 and on the brink of WWII, de Lempicka marries Baron Raoul Kuffner and the couple move to the United States. She chooses a destination to match her aspirations and lifestyle: Hollywood. However, the reception afforded her in the United States is not what she expected - in her new home she is considered a "hobby" artist who painted for fun. In 1949, they move again, this time settling in New York where she continues to paint but in a style more reminiscent of the Old Masters than her work from the 1930s. She also dabbles in interior design, creating makeover projects for the homes of high society clients.

Final years in Mexico

In 1962, Lola's Gallery in New York held a solo exhibition of de Lempicka's work. The critical reception was lukewarm but she persevered with her painting, regardless. That same year, her husband died suddenly and she moved to Houston to be closer to her daughter who lived there. In her final years, de Lempicka decided to move to Mexico, a country that became her final home, having always been close to her heart.

In 1972, the Luxembourg Museum in Paris organized an exhibition that rekindled public interest in her work and brought about the artist's reconciliation with critics. In 1980, de Lempicka died and, following her express wishes, she was cremated and her ashes scattered around the foothills of Popocatepetl volcano.

Exhibitions

Tamara de Lempicka (2015)

In 2015, the Italian city of Turin exhibited the well-known "Girl in Green", on loan from the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which triggered a large retrospective of de Lempicka's work that filled out galleries in the Polo Reale museums and the Chiablese Palace.

The many faces of Tamara de Lempicka (2019)

“The many faces of Tamara de Lempicka” was the name the Kosciusko Foundation of New York chose for its retrospective of the artist. The exhibition afforded the public an opportunity to admire a wide selection of paintings and drawings documenting the artist's life during the nearly six years she spent in the artistic capital of America.

Tamara de Lempicka: Queen of Art Deco (2015)

In 2019, The Gaviria Palace organized a grand exhibition on the "Queen of Art Deco", with a view to reigniting the Madrid public's interest in de Lempicka's painting. The retrospective brought together over 200 works in total, loaned by nearly 40 public and private collections against a backdrop of magnificent Art Deco design objects from the period.

Books

“De Lempicka”. Giles Néret (Taschen)

The German publisher Taschen does an excellent job of compiling de Lempicka's oeuvre in this essential guide. In it, historian, journalist and art conservator Gilles Néret frames the painter's work within the collective memory of the 1920s and the history in general of women artists.

“Passion by Design. The art and times of Tamara de Lempicka (Revised)”. Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall (Abbeville Press)

Who better than her own daughter, Kizette, to do a fascinating analysis of Tamara de Lempicka, the person? To this day, the book remains the definitive compilation of her life and work. The new edition is illustrated with excellent reproductions of her most famous works and includes never-before-seen documentation, including private photographs from family albums. The introduction is written by Marisa de Lempicka, great-granddaughter of the painter.

“Tamara de Lempicka”. Virginie Greiner and Daphné Collignon (Planeta Cómic)

Nothing like art to illustrate (or recreate) part of de Lempicka's life. In this case, it is that of V. Greiner and D. Collignon, creators of a graphic novel full of beauty and passion. A book that reflects de Lempicka's talent, freedom and powerful personality in fictional form.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Tamara de Lempicka: Biography, works and exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Two lives parallel in time, two like-minded ways of understanding the world and a piece of drawing paper that would forever bring together two of the great creatives of the first half of the 20th century. I refer to Paul Klee (1879-1940), Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and "Angelus Novus", a small work of art measuring just 32x24 cm and monoprinted in 1920.

|

Collaborating Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Angelus Novus

"Since Homer’s time, the greatest narratives have followed in the wake of great wars, and the greatest narrators have emerged from the ruins of devastated cities and landscapes.” H. Arendt

Two lives parallel in time, two like-minded ways of understanding the world and a piece of drawing paper that would forever bring together two of the great creatives of the first half of the 20th century. I refer to Paul Klee (1879-1940), Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and "Angelus Novus", a small work of art measuring just 32x24 cm and monoprinted in 1920.

During a June 1921 visit to Munich, Walter Benjamin, accompanied by his long-time friend Gerschom Scholem, visited Hans Goltz's gallery on Odeonplatz to buy the "Angelus Novus", a painting that had had such a profound impact on him a year earlier in Berlin.

Klee had for some time been seeking out new ways to portray reality and new figurative possibilities. In his book "Creative Confession" of 1920, he begins by saying, "Art does not reproduce the visible, rather, it makes visible [what is invisible]." A tendency towards the abstract is inherent in linear expression and rightly so: graphic imagery confined to outlines has a fairytale quality whilst at the same time achieving great precision.

For Klee, form would become the catalyst element deriving naturally and directly from the imagination to unleash a new creative freedom aimed at expressiveness and immediacy. The figurative should blend with one’s conception of the world (1916). It is through the artist that Nature creates.

Angels, by definition of an uncorrupted nature, are a form of direct expression and an attempt to balance out the progressive, technological world with the spiritual world, of which Benjamin would later speak. They constitute a symbolic resource that captured the outrage he felt for all that was happening at a time of immense uncertainty in which certainties had lost their value. He needed to fantasize and angels were a means by which to go beyond a reality that was too prosaic. "To extricate myself from the ruins, I had to fly. And so I flew. In this shattered world, I only live in remembrance, just as sometimes one thinks of something from the past. That's why I'm abstract with memories" (1915). The same ruins that would later pile up at the feet of the 'angel of history'.

"The more terrible this world becomes, as is now the case, the more abstract art becomes." (1915). That year, his friend and fellow artist Franz Marc died on the Western Front at the Battle of Verdun. Klee and Benjamin shared a turbulent world that made its mark on their lives and work. They were both looking for a way to shape their thinking. For Klee, what we perceive is a proposition, a possibility, the authentic truth at its base, albeit invisible (1916). For Benjamin, the truth is in the most insignificant representations of reality.

“Something new is announced, the diabolical is inextricably linked with the celestial, dualism will not be treated as such but in its complementary unity. Conviction already exists. The diabolical is already peeking out here and there again, and it is impossible to suppress it. For truth demands the presence of all the elements as a whole." (10 June 1916). Again the image of the angel is conjured.

Benjamin gives us an account of his own interpretation of Klee's painting, without in any way compromising the artist's intentions regarding these images of contemporary angels that interested him so much and harboured so many ideas.

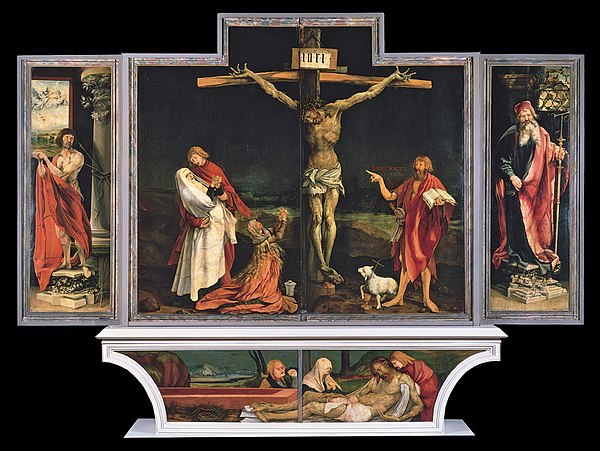

The "Angelus Novus" image became a recurring obsession in Benjamin's thinking. It always took pride of place in his studio and it seems he positioned it next to a reproduction of the Isenheim altarpiece by the German painter Mathias Grünewald, a work of tremendous drama that strips human misery bare. Might he have seen parallels between the two images?

The Crucifixion. Central panel of the Isenheim altarpiece. Matthias Grünewald. Museum of Unterlinden, Colmar, France

The head of the "Angelus Novus" is covered with strylised, curly hair and disproportionate to the size of its body. The feet resemble bird's claws and the wings are attached to the hands. The body houses a pendulum inside a tower ~ that harmonious and silent element marking movement and time that so intrigued Klee and so tormented Benjamin. Huge, wide-open eyes stare past us, to somewhere outside our field of vision. His mouth is half-open and it looks like he is about to say something. The "Angelus Novus" is bringing a message and awaits an answer through his outsize ears. Everything seems to fit for Benjamin ~ this is the Angel of History. Things reveal their significance to him in secret.

There is a painting by Klee called "Angelus Novus" depicting an angel contemplated and fixated on an object, slowly moving away from it. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth hangs open and his wings are outstretched. This is exactly how the Angel of History must look. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it at his feet. Much as he would like to pause for a moment, to awaken the dead and piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Heaven, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which he turns his back, while the heap of rubble in front grows sky-high. What we call progress is this storm.

This is the full text of thesis IX from "On the Concept of History", an essay comprising eighteen theses that constitute a reflection on the idea of progress and its consequences within the concept of history. This was a cornerstone of Walter Benjamin's thinking wherein he questions the era of modernity and the idea of progress it underpins, through one’s ability to give material form to the invisible. Written during his last months in Paris, on the eve of its German occupation, and concluded days before he left the city for a failed exile. His plan was to cross Spain into Portugal and there embark on route to the United States where his friends, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno and the Institute of Social Studies awaited him.

Deeply worried about an overly uncertain future and before leaving the French capital, Klee entrusted his friend George Bataille with a suitcase containing his most treasured possessions, the "Angelus Novus" and his latest writings, among them the manuscript of "Theses on the Philosophy of History", with instructions that, should anything happen to him, he would ensure they reached Theodor W. Adorno. The essay was published by Adorno in a special issue of the Institute of Social Studies in 1942, thanks to the copy that Benjamin had given to Hanna Arendt and which she, albeit reluctantly, passed on to Adorno. The painting ended up in the hands of Gerschom Scholem, at Benjamin's express wish. Scholem's book, "Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism", had been a fundamental inspiration for his work and is currently part of the Jerusalem Museum collection.

The "Angelus Novus" is an exceptional representation of the importance of movement in transformation and evolution and of the importance of looking to the past to build the future. The passage of time has only served to increase its powerfulness and seal its immortality.

Walter Benjamin and Paul Klee

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Paul Klee -Angelus Novus- Walter Benjam - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

Long after her death, Frida Kahlo has ultimately transcended her own reality. From revolutionary painter, creator of intimate worlds and a woman tortured and wronged but also open to love, her public image has since become that of a veritable icon, perhaps even to the point of tipping over into a dangerous banality. But the millions of images of the artist that have become merchandising do not in any way detract from the enormous power of her work.

Art with wings to fly

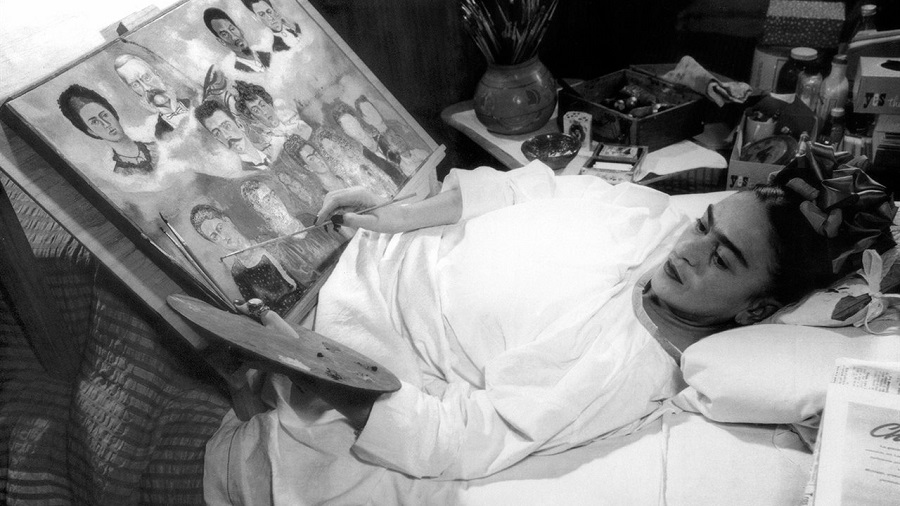

Frida Kahlo painting “Portrait of Frida's Family”. Photo: Juan Guzmán,1950-51 from www.historia.nationalgeographic.com.es

Long after her death, Frida Kahlo has ultimately transcended her own reality. From revolutionary painter, creator of intimate worlds and a woman tortured and wronged but also open to love, her public image has since become that of a veritable icon, perhaps even to the point of tipping over into a dangerous banality. But the millions of images of the artist that have become merchandising do not in any way detract from the enormous power of her work. Kahlo's potential and talent flourished through sickness, suffering and prostration. In her own words, "Everything can be beautiful, even the worst horror". She was also able to turn herself into works of art with their own entities, following in the wake of other artists such as Salvador Dalí.

Rooted in her own culture and a lover of beauty (her own and others’, within and without), Kahlo’s image and persona enjoy actual cult status in Mexican society, where portraits of her even take pride of place in altar places dedicated to other saints. In life, Kahlo was faced with a terrible reality and used art to show her suffering, overcome it and learn to live with it. And she did not have far to go in order to create her own personal imaginary, so admired by artists like André Breton, saying "I never paint dreams or nightmares. I just paint my own reality."

Childhood, apprenticeship and tragedy. The early years.

Magdalena del Carmen Frida Kahlo was born in the famous Casa Azul (The Blue House) in Coyoacán, Mexico City, in 1907. Her father, Guilermo Kahlo, had emigrated to Mexico from Germany in 1890, at the age of 19. Frida was the third of four children to Matilde Calderón, Guilermo’s second wife, the first, with whom he had had two other daughters, having died in 1884. In her early childhood, the budding artist lived a life of luxury, resulting from her father's profession as a jeweler to Mexican high society and his work as a photographer, which he took up after his second marriage. However, after the end of Porfirio Díaz's rule (known as "The Porfiriato"), the family began to experience serious money problems.

La Casa Azul, now the Frida Kahlo Museum

In 1913 and at the age of six, Frida was diagnosed with polio and bedbound for 13 months, her first contact with the disease which was to become a permanent shadow throughout her life. Although she managed to recover and despite her right leg being seriously deformed, as a little girl she was already showing early signs of her ability to overcome adversity and began assisting her father in his work, participating in tasks such as developing, retouching or taking photographs. This collaboration was her first, and a fundamental, contact with art.

In 1922, Kahlo enters the National Preparatory School where she comes into contact with the most progressive ideas of her time. Intelligence and talent are her best defense against the taunts occasioned by her limp but her forceful personality wins out and she becomes a member of the group ‘Los cachuchas’, where she meets her first boyfriend, Alejandro Gómez Arias. In 1925, the bus on which they were both travelling collides with a tram. The accident causes Frida multiple fractures throughout her body and greatly exacerbates the poliomyelitis in her right leg.

Painting as salvation and a means of expression

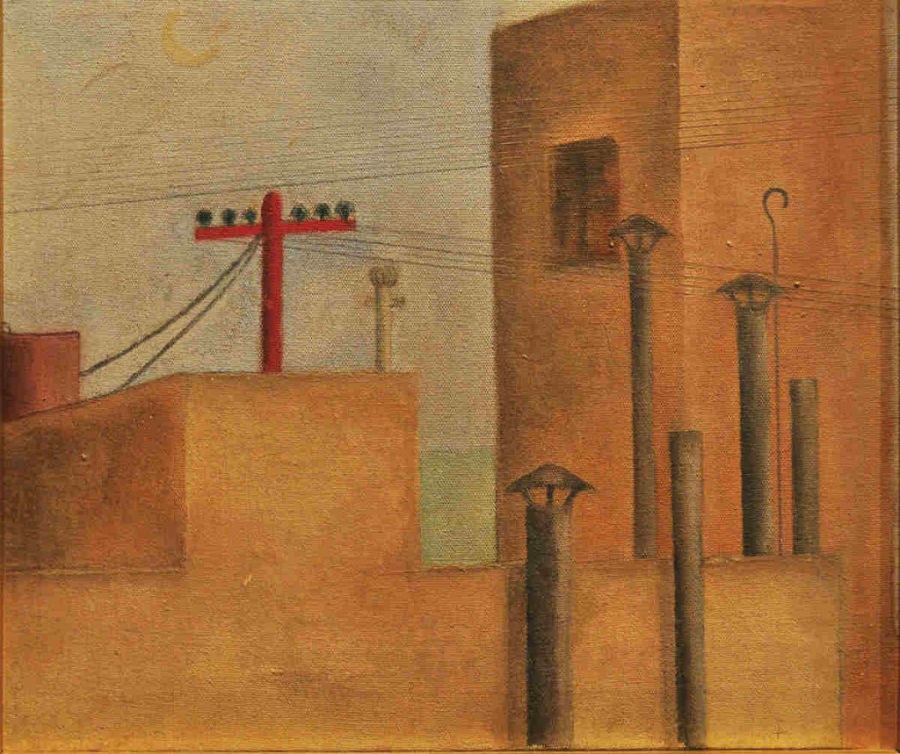

“Urban Landscape”, circa 1925. From arquine.com

Bedridden, her father gifts her a box of paints and brushes. It is the beginning of her unbridled passion for the art that would be her companion throughout countless periods of prostration and serve as psychological alleviation from the constant pain that would never leave her while she lived. As Frida herself described it, she began painting in bed "with a plaster corset that went from the collarbone to the pelvis", with the help of "a very funny device" - an angled contraption devised by her mother to support a stiff board and paper.

In one of her earliest works, "Urban Landscape" (circa 1925), some of what would become constants in her pictorial trajectory were already discernible. Painting was not an end in itself but a means by which to explore reality and portray a series of sensations. The landscape, anodyne and austere, is not of the utmost importance. According to the writer and biographer Araceli Rico, the work shows a space that is "narrow, reduced to inconceivable dimensions [...], a small theatre staging her own life".

Exploring her identity. Self-portraits

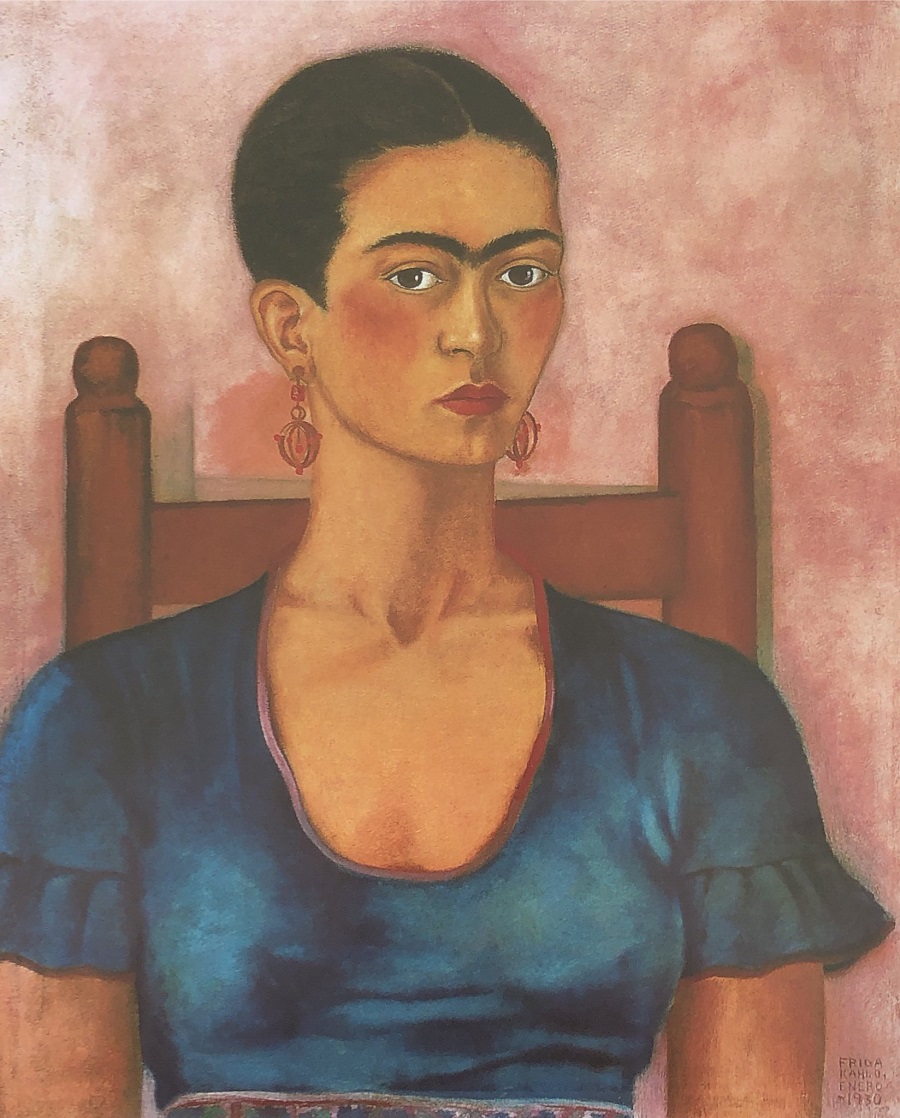

“Self-portrait” (1930). From westwing.es

Kahlo's enforced prostration led her to examine her own person, her body and her identity. A mirrored panel above the bed allowed her to embark on the famous series of self-portraits she painted throughout her life. At first, they were austere portraits of a woman with piercing eyes but over time, they would also come to reflect raw emotion, suffering, passion and desire. And although these works would make her an "object of desire" for the Surrealist movement led by André Breton, she never saw herself as a Surrealist painter: in her own words, "Surrealism doesn't correlate with my art. I don't paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality, my own life."

“The Two Fridas” (1939). From inbal.gob.mx

Throughout her life, the exploration of self-identity was a constant in Kahlo's work. In addition to the self-portraits that constituted the most common subject matter of her artistic output, she also reflected on her family ancestry, her friends, romantic partners and close relatives. All of them blended the powerful, primary colors so characteristic of Mexico's plastic and aesthetic cultures, their emotions expressed through visual metaphors: thorn necklaces, animals, blood, tears, corsets ... Her first self-portrait was dedicated to her then boyfriend, Gómez Arias, who distanced himself from her after the accident. Although Kahlo suffered deeply from the breakup (while the young lawyer downplayed their relationship), she would keep in touch with him for the rest of her life.

Diego Rivera. Love, loathing and despair

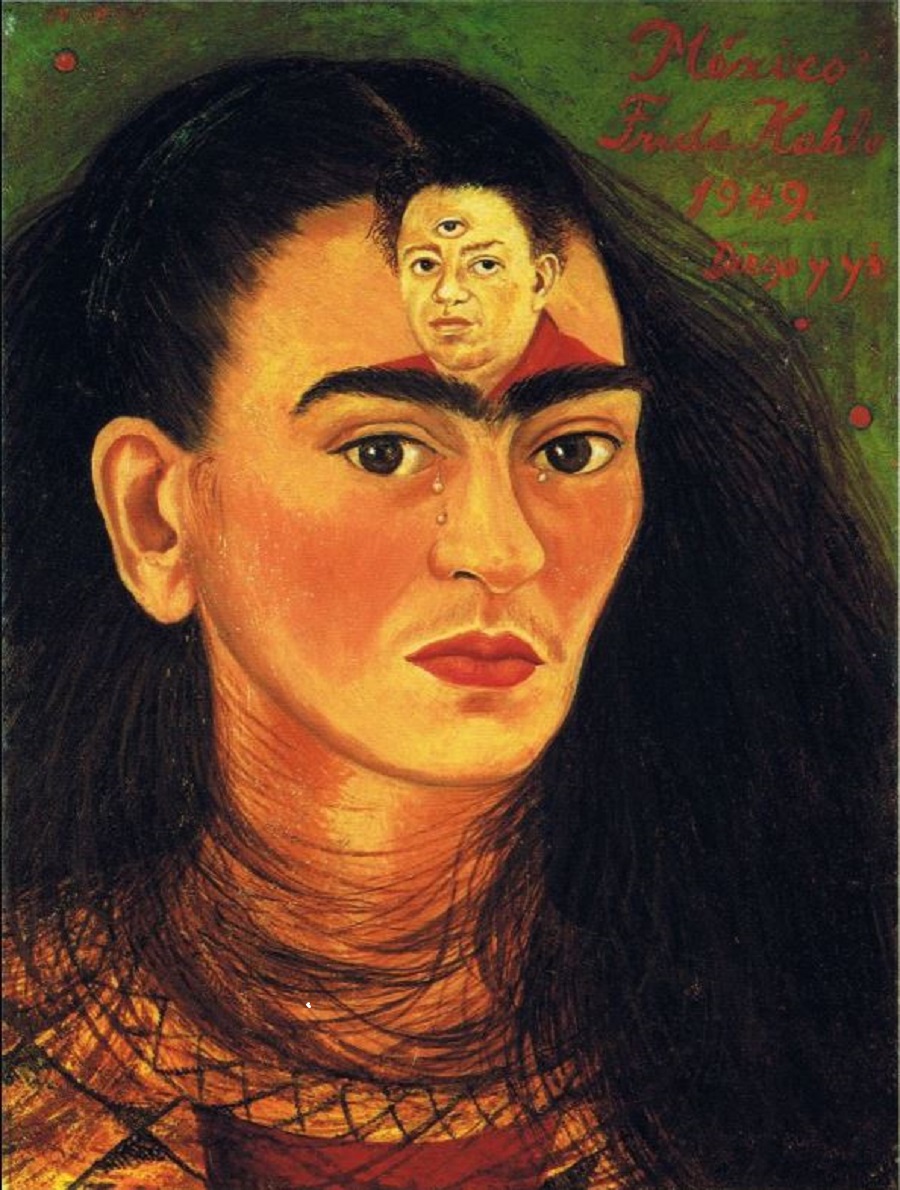

“Diego and I” (1949). From i.pinimig.comm

The accident that destroyed Kahlo's skeletal structure was never an obstacle to her social and cultural activities. From adolescence on, she was no stranger to Mexico City's artistic and political circles. Through the photographer Tina Modotti, she was introduced to the muralist and painter Diego Rivera, who would become the love of her life in a relationship marked by passion, disillusion, jealousy and infidelities. Kahlo painted him on several occasions and described her feelings for him in her diary with phrases such as "I feel that since our very origins, we've been together, that we're of the same matter, on the same wavelength, that we carry within us the same sensibilities" making clear the intensity of her love which was both powerful and destructive.

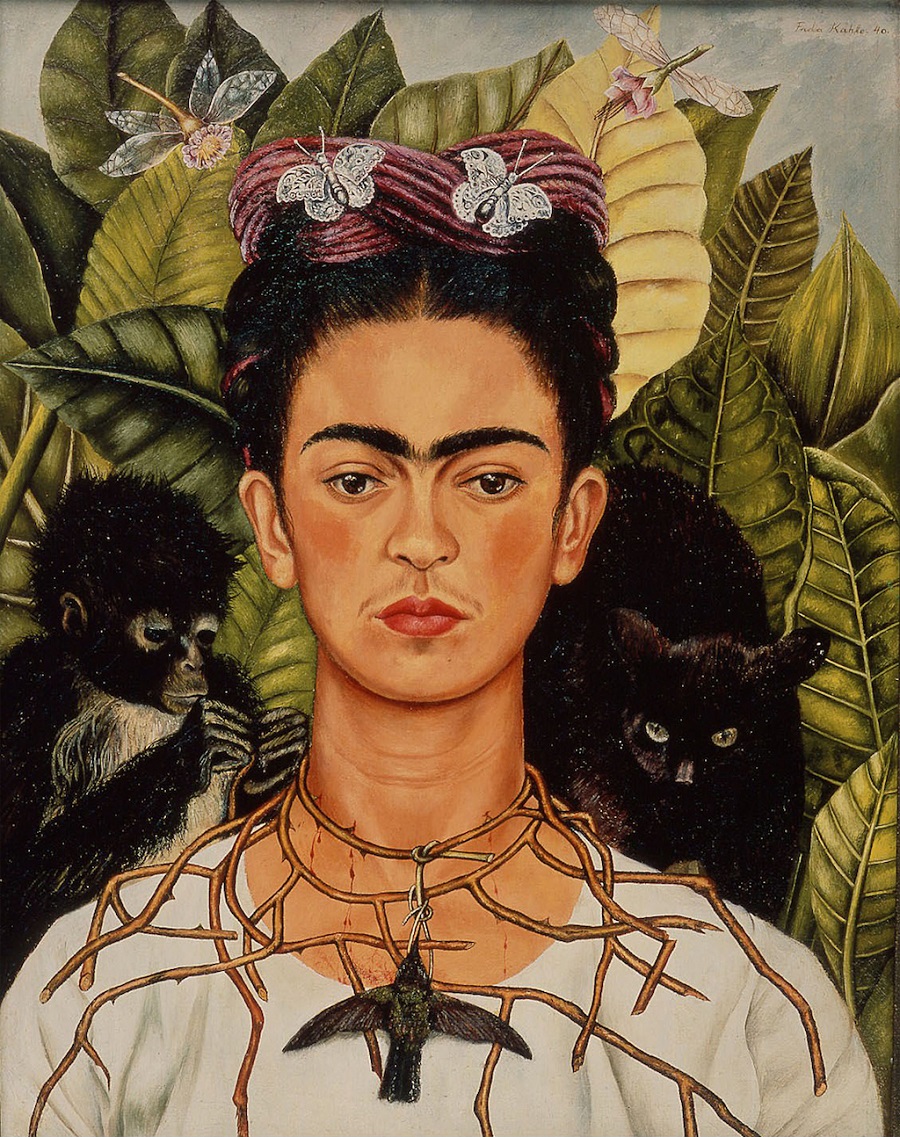

“Self-portrait with thorn necklace” (1940). From matadornetwork.com

In 1929 and at the age of 22, Frida Kahlo married Diego Rivera, who was then 43. It was "the marriage between an elephant and a dove," in her words. During the ensuing years, they lived together in La Casa Azul (The Blue House), spending long periods in the United States. In this house, and later in the current Studio House Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, the couple keep up an intense cultural and social life characterized by their political commitment to left-wing ideals. In fact, between 1937 and 1939, they would offer asylum to Leon Trotski and his wife who had been persecuted by Stalin. Frida and Diego's relationship underwent countless ups and downs due to the muralist's infidelities, to which Kahlo chose to respond with her own. They divorced in 1939 only to remarry in 1940, this time with a commitment to an 'open' relationship.

The final years. A decade of activity, passion and pain

“Hopeless” (1945). From es.blastingnews.com

The 1940's were a decade of intense artistic activity for Kahlo but although she was long thought to have been overshadowed in life by Diego Rivera's powerful presence and did not at that time achieve the fame afforded to her husband, her work was indeed recognized by artists such as Breton, Picasso and Kandinsky, among others. In 1938, the Julien Levy Gallery in New York organized the first solo exhibition of her work and she began participating in collective exhibitions. Her work was exhibited in Mexico, Paris, New York, Boston and other American cities. In 1942, she joined the Seminary of Mexican Culture as a founding member and in 1943, she joined the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving "La Esmeralda" as a teacher. In 1953, the year before her death, the Lola Alvarez Bravo Gallery organized a solo exhibition of her work in Mexico City which would turn out to be the only one held in the country during her lifetime.

“Frida's Eyes” (1948). From bodegonconteclado.wordpress.com

Kahlo's physical and medical problems left her incapacitated in bed for long periods but she persevered with her painting and created magnificent portraits full of symbolism, depth and personality. This was the case with "Frida's Eyes" (1948), a work that reflects two of the constants in her painting: suffering and a passion for Mexican traditions. Pain and the proximity of death, which Kahlo felt was fast approching, are recurring themes on her canvases. In 1950, her health deteriorated due to spinal surgery that caused her significant problems. In 1954, Kahlo attempted suicide twice, unable to endure the pain any longer. That same year, Kahlo died at the age of 47 and her coffin, draped with the Communist flag, was placed in the capital's Palace of Fine Arts, where the most prominent Mexican artists and intellectuals of the day came to pay their respects.

Exhibitions

Frida Kahlo (2010)

In 2010, Vienna's Kunstforum organized one of the largest ever retrospectives of Kahlo’s work. In total, the exhibition included some 150 works, among them many of her most famous self-portraits.

Frida Kahlo. “Paintings and drawings from the Mexican Collection” (2016)

Kahlo's connection with the Soviet Union dates back to her youth. She always expressed her commitment to communism, social engagement and the most vulnerable members of society. In 2016, present-day Russia organized an exhibition in her honour at the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg: it was the first time her work had ever been shown in the country. The exhibition included some 34 pieces including paintings, drawings and photographs.

Frida Kahlo: "I paint myself” (2017)

"I paint myself because that's what I know best." These are the words with which Kahlo justified her obsession with self-portraiture. The exhibition held at the Dolores Olmedo Museum in Mexico City was a compilation of 26 works from the museum's own collection returning home although for a limited time only, as they are constantly out on loan to exhibitions around the world.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances can be deceiving (2019)

Kahlo's unique and inimitable style was without doubt an indissoluble part of her own identity and what made her an omnipresent plastic and aesthetic icon of the 21st century. The artist defined herself in her paintings and in her persona through illness, political engagement and cultural kinship. This Brooklin Museum exhibition was the largest in the United States for ten years and, in addition to paintings, included personal items, clothing and intimate treasured possessions only discovered in 2004.

Books

“The Diary of Frida Kahlo: an intimate self-portrait ”. (La Vaca Independiente)

Frida Kahlo’s life and personality, as well as her work, cannot be understood in all their magnitude without reading her diary. Written during the last ten years of her life and locked away for nearly 50 years, it is a raw testament to the painter's private feelings. Illustrated with fantastical watercolors and shot through with her unbridled and destructive passion for Diego Rivera, the journal has a prologue by the author Carlos Fuentes and includes an essay by Sarah M. Lowe. 170 pages of art, emotion and intimacy.

“Frida Kahlo: Beneath The Mirror”. Gerry Souter (Parkstone Press)

Frida Kahlo used herself as the exclusive model for dozens of self-portraits. It is precisely these works that conceal and distill the essence of her life, her history and her feelings. They are, without a doubt, the best autobiographical testimony we have of the artist. Gerry Souter's biography uses these works and other paintings to articulate her story. The writer later wrote a second volume dedicated to Kahlo's husband and muralist and painter Diego Rivera.

“Frida Kahlo: Fantasy of a Wounded Body”. Araceli Rico (Plaza y Valdés)

The author Araceli Rico was one of the first to recognise the enormous importance of Frida Kahlo's work in the sphere of world art. Page by page and word by word, the internal tension that Kahlo always experienced is revealed, as is the symbiosis she experienced between art and life, body and painting. This is an essential book to get to know both the person and the painter, both trapped in the same body, both loved and tortured.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Frida Kahlo: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Until 18th October, Berlin's Museum of German History will be hosting the exhibition "Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century" which provides the perfect pretext to focus attention on one of the finest minds to have cut a swathe through the history of modern thought. The value of testimony from one of the freest thinkers in the field of political theory is all the greater since it comes from Arendt's own lived experience and is based on an absolute independence of reasoning over and above conventionalism of any kind.

Author: Elena Cué

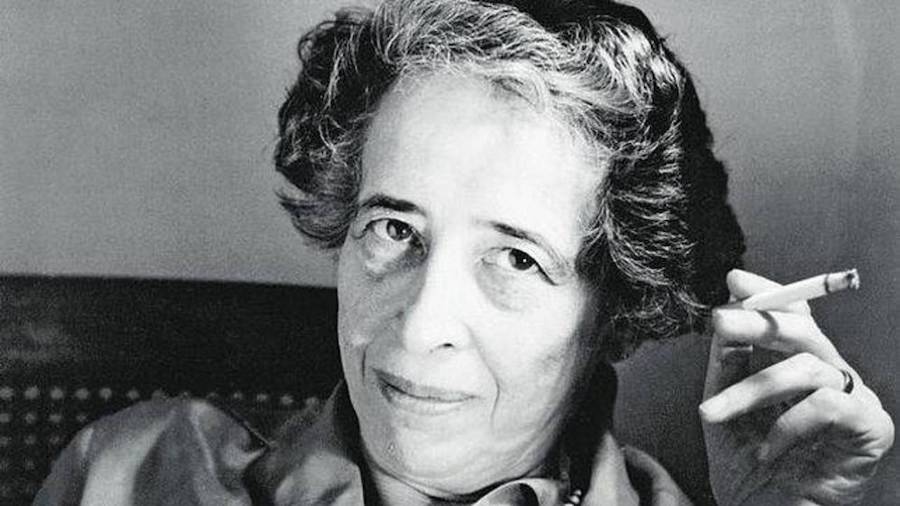

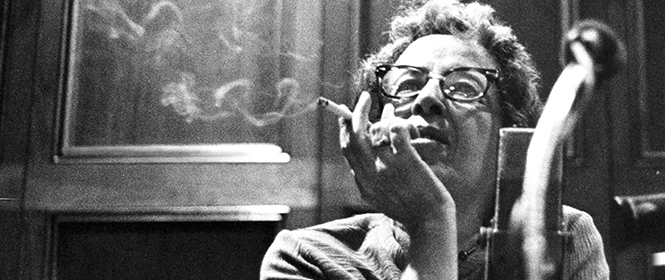

Hannah Arendt

Until 18th October, Berlin's Museum of German History will be hosting the exhibition "Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century" which provides the perfect pretext to focus attention on one of the finest minds to have cut a swathe through the history of modern thought. The value of testimony from one of the freest thinkers in the field of political theory is all the greater since it comes from Arendt's own lived experience and is based on an absolute independence of reasoning over and above conventionalism of any kind.

It was this freedom of thought that led to the critical questioning of Arendt throughout a 20th century in turmoil. But it was also due to her thinking being a timeless, open discourse that lays no claim to being conclusive. Reluctant to see history as a continuous line of progress culminating in a conclusion, she thinks with critical vision from the present moment in time.

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), a German philosopher of Jewish origin, was the victim of anti-Semitism and the repression of a political totalitarianism that made her, first, stateless and later in the United States, a refugee deprived of legal or moral rights, a condition that made Jews, wherever they went, in her own words - "the scum of the earth".

The thinking of this leading figure in political theory is very difficult to label. She reflected in depth on the great, dauntingly complex issues of the 20th century such as anti-Semitism, the status of refugees, totalitarianism, Zionism, racial segregation in the US, student protests and feminism, all of which are analysed not only from what might have been the heights of an intellectual ivory tower but also from her own personal experience. Through objects, documents, articles, letters and family mementoes and even a section dedicated to her friends, this exhibition is an invitation to think for oneself, outside the box of any dominant discourse.

Hannah Arendt

- Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

A little over a month ago, on 20th April 2020, one of the greatest photographers of the last three decades died aged 92. Gilbert Garcin, whose artistic career began on his retirement from the job he had devoted his whole life to - a small lighting manufacturer in Marseille - was 65 years old when a whole other world opened up before him ... that of photography.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

A little over a month ago, on 20th April 2020, one of the greatest photographers of the last three decades died aged 92. Gilbert Garcin, whose artistic career began on his retirement from the job he had devoted his whole life to - a small lighting manufacturer in Marseille - was 65 years old when a whole other world opened up before him ... that of photography. What kickstarted his new lease of life was a course he enrolled on at the 1995 "Les Rencontres d'Arles" Festival and from then on, nothing would ever be the same again for this budding sexagenarian artist. The recently-opened Paris Photo Salon of 1998 afforded him the opportunity to get his work known internationally and take him, in a very short space of time, to the highest heights of success at photography.

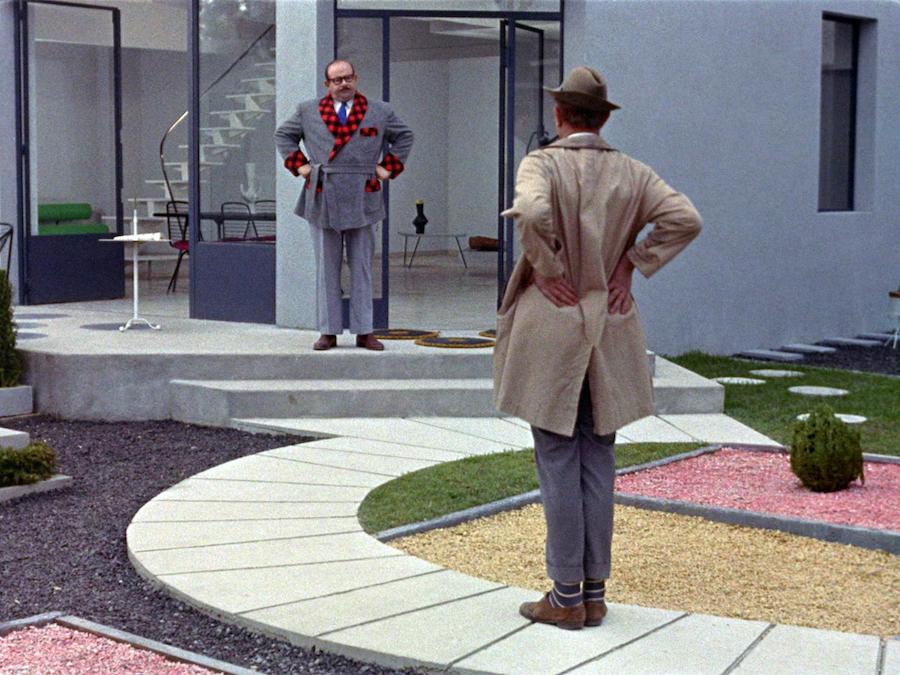

Through his images, we see a new world where simplicity and complexity walk hand in hand, creating new realities and turning the absurd into the commonplace. His way of looking at things transforms objects into something different, placing them 'through the looking glass'. It is perhaps this that linked him, by his own acknowledgement, to the filmmaker Jacques Tati and the Belgian painter René Magritte. Like them, Garcin shows us how to see a new world between the visible and the invisible, the real and the imagined, the borderline between the conscious and the unconscious. The photo montages, or staged photos as he called them, are the ideal means by which to create those mysterious images with elements of surprise that run throughout his work and manage to say the unsayable. He had great trouble choosing titles for his photos and he himself often found no explanation at all for his own creations. I am quite sure André Breton would have been fascinated by the compositions Garcin created and captured with his analog camera, optical inventions that never lose their naivety and humour, and where everything is false and real at the same time. His photos also have something of the metaphysical, those geometric representations that intertwine with the human figure in search of a change of relationship and meaning in order to build new associations.

Behind every snapshot creation is a craftsmanship that took between 20 and 30 hours of studio work. On the table of his modest workshop in Ciotat, Garcin would stage the different scenarios, sometimes skies borrowed from 19th-century painters, other times small sandy surfaces or linear compositions inspired by Paul Klee's drawings or even vintage film reels on which he would overlay his image, laid out on a stand. The viewer, on approaching any of his photos, will discover their play on scale, their imperfections and the naturalness and uniqueness that encapsulates each of them.

Garcin's work is so personal that he himself models for his own photos. It is he who functions as a working part of his creation, he is the actor playing the leading role and he who directs and calls the shots at will, according to circumstance. He has said: "It's not me, it might be my double, but essentially you have to see him as a character."

Perseverance

He made his first appearances wearing a hat that he soon abandoned in favour of an overcoat he had inherited from his father-in-law, a family heirloom which he kept as his hallmark until the end of his career. On occasion, he includes his wife as an indispensable complement to his storytelling.

It would seem that the only references to actually influence his work are found in films of the 1920s and 1930s. His grandfather, Auguste Garcin, ran a small cinema where, in the 1890s, the Lumiere Brothers films were screened and where he lost himself in the silent films of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin.

The deep sense of loneliness and atemporality that permeate his work make him an artist of great intuition, sensitivity and awareness of the unsettling world we have to live in, always leaving the interpretation up to each observer. Conveying without imposing.

An atypical artist and modern-day craftsman who created, with simplicity and an unbounded poeticism, a disjointed unity that made him a genius. And quite simply, moving.

Gilbert Garcin Photography

Organised by the photographer José Ferrero in the spring of 2017, the Niemeyer de Avilés Centre held the exhibition “The utopias of Gilbert Garcin” showcasing over 80 works by the French photographer.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Gilbert Garcin - Making the Meaningless Meaningful - - Alejandra de Argos -