- Details

- Written by Rafael Luque

Trying to review Romanian-born artist Anka Moldovan’s latest exhibition "that which bursts" is, I have to admit, an excersize in arrogance, akin to claiming one can describe the joy felt by a sparrow in flight or the beauty of Handel's "Son nata a lagrimar". It is unwise to even attempt to reduce down to a few words the complexity of her worlds which, while still our world, feature exotic singularities like the event horizon of a black hole.

"Slit-man. Retina" (detail) (2023). Oil on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Trying to review Romanian-born artist Anka Moldovan’s latest exhibition "that which bursts" is, I have to admit, an exercise in arrogance, akin to claiming one can describe the joy felt by a sparrow in flight or the beauty of Handel's "Son nata a lagrimar". It is unwise to even attempt to reduce down to a few words the complexity of her worlds which, while still our world, feature exotic singularities like the event horizon of a black hole.

The beings and ambiences that emerge, pertinatious, from her paintings seem to live on that mysterious fine line between the visible and the invisible, between being and disappearing. Although it would be easy to divide the collection into four categories, there is still a common denominator that forms part of Anka Moldovan's identity as a creator: namely, her efforts to make the air perceptible, the constant human presence, somewhere between the corporeal and the abstract (despite which it is still possible to recognize oneself in some or other of her pedestrians walking with the determination of those who know and own their responsibility) and an undeniable capacity for synaesthesia.

Painting is, in principle, a visual art but, in this case, there are other senses involved. It is impossible not to feel the urge to touch, as if we were blind and reading Braille, the roughness of the reliefs that are an essential part of her work. Their meaning is as suggestive and mysterious as the "Voynich Manuscript" that, 600 years after its writing, remains indecipherable. Moldovan’s paintings smell of the rain and the sea because the beings in them seem always to be living in a thick fog that they wade through fearlessly in order to find us although, along the way, they run the risk of suffering a “Sudden Departure”, a euphemistic linguistic construct used to refer to the disappearance of 140 million people in the series "The Leftovers".

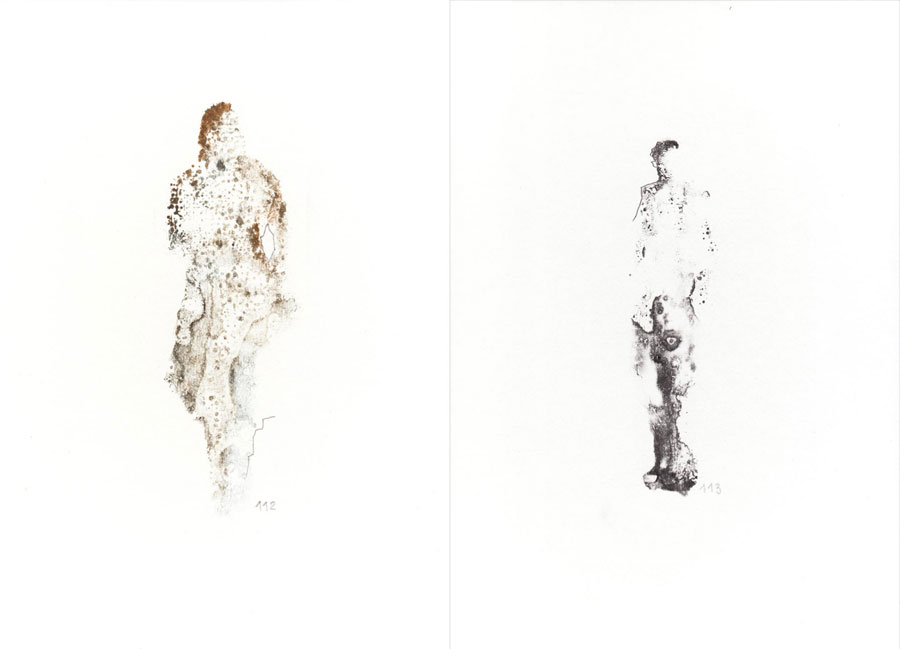

This happens in real terms in Moldovan’s work and comprises the "Reflections" collection - individuals who come to life in her paintings and, in the laborious construction of the fog, with its layer upon layer of oil painted and removed time and time again in search of a veladura glaze, it sometimes happens that one character is transformed, another vanishes into thin air, another fades away and, through a process of transference, is reborn on paper. The price of the pilgrims’ odyssey is to live alone, behind numbered windows and to be the only, or unique rather, creatures who are distanced from the firm, natural support of wood and exist on the human construct of paper. Odd observers these, echoes who from afar observe the paintings from which they come, each one a foreigner who discovers that the best way to accept what they have become is to remember what they once were, as Theodor Kallifatides wrote.

"Reflection 112" and "Reflection 113" (2023). Oil on paper. Courtesy of the artist

Moldovan's work can also be heard because it is narrative, it tells a story, incomplete, fragmented, like the name itself of this exhibition, "that which bursts", barely half a sentence, a subordinate clause lost in a world, our world, full of noise and fury, that shouts without listening and speaks without saying a thing. The art critic Carlos Delgado Mayordomo defines with poetic and meticulous precision: "Pain and love, despair and joy, absence and presence, are – without being exhaustive – some of the recurring themes in her paintings, where the desire to liberate and elevate what is properly human, to transcend it, is always visible."

What we see are troubled beings, carrying the burden of great responsibility, exhausted but not defeated, in pain, determined and ethical. Every paradise is a paradise lost and the visions that the creator portrays remind us that life rhymes with strife and not by chance but by causality. This is nowhere more evident than in the “Slit-men” suite - a transubstantiation of a poem by Nichita Stănescu that describes someone who “comes from beyond / and even beyond that beyond.”

Anka Moldovan, work in progress

The best way to describe them is the photograph above where Moldovan observes her "Slit-man. Presence" with the fascination and curiosity of an entomologist witnessing the arrival of the first insects on a corpse and, given the comforting gesture with which she touches her hair, it would seem that he is a stranger even to her. The four "Slit-men" are subtitled "Presence, Retina, Belly, Breath" and are entities somewhere on the spectrum between the savage and the human. They have arrived, although not through some fancy wormhole but by headbutting their way in. Seeing them gives new meaning to the scene in “Bladerunner” where the replicant Batty's face smashes through a tiled wall in pursuit of Deckard. In these four paintings, of the same height as the artist herself, there is hunger, pain and an intimidating power. They watch us and they see us.

If “Reflections” and “Slit-men” concern being rootless or uprooted, then the paintings from the “Earth” series are literally rooted, with actual roots.

"Earth" (2023). Oil on wood with root. Courtesy of the artist

They are women's heads with eye-catching buns and ornate up-dos, details that form part of the author's memory and memories. Another place, another time, other women and their ancestors, captured in a trivial detail that is testament to their greatness and generosity because their delicate and laborious braiding is seen by everyone else except they themselves. A root emerges from their hair because these women, in 1980s Romania, had their feet firmly on the ground and carried out their duty to care, feed, educate, provide love and security, sow responsibility and empathy and, ultimately, build true human beings.

Above left: "Birthing the world" (2021). Oil on wood. Above right: "Man, joy" (2023). Oil on panel (2023). Courtesy of the artist

With the root of a raspberry bush sprouting from her plaited hair, the natural and the artificial, nature and art share the same space. “It is not a simple stylistic artifice, but a bold reflection on the inevitably symbolic foundation of the visual arts: the roots, without the need to lose their own physiognomy, are read as a coherent part of human representation” according to Carlos Delgado Mayordomo.

And then finally, we come to the walkers, beings similar to us who move through spaces that we recognize (such as Madrid’s Gran Vía), prosaic passengers, citizens who inhabit the months as others inhabit cities and others metaphors. What makes them a society, while still remaining individuals, is that they are essentially beautiful and noble, physically and morally. Committed and empathetic, always moving forward without avoiding life's challenges. It is their greatness that makes me think that they only seem similar to us although, through the kind and loving eye of their creator, it is possible that we ourselves may become free from our sins.

Tireless and determined, they are surrounded by a mystical atmosphere that could be their soul, because they have one, or the air they exhale, because they breathe. One of these works, "Birthing the world" became the cover of the novel "A woman in the making" by Christian Bobin. This carefully crafted edition published by “La Cama Sol” makes for an illustrated book in a double sense, where the words of the gone-too-soon writer of silence and the paintings of the painter-of-air coexist.

"The flow of air". Oil on panel. Courtesy of the artist

"The mystery that bursts from her paintings - explains Carlos Delgado Mayordomo - is not just the expression of beauty but the celebration of life." Whether solid as concrete or ethereal as shadows, Anka Moldovan's beings whisper stories of resistance and hope. The latter is a necessity whereas the former is an act of love, the necessary defeat of oblivion and indifference - the stubborn will to keep asking questions, even if we sense we will never know the answers.

Translated from the Spanish "Los otros mundos de Anka Moldovan" by Shauna Devlin

- The Other Worldliness of Anka Moldovan - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by José Lázaro

Many are the creators who, throughout history, have believed they saw the origins of creativity, or at least some of its requirements, in good health and a feeling of wholeness. But neither are they few those who found the best stimuli for their creations to be suffering and sickness. Some seem to heed Horace’s advice to "delight and instruct"

Many are the creators who, throughout history, have believed they saw the origins of creativity, or at least some of its requirements, in good health and a feeling of wholeness. But neither are they few those who found the best stimuli for their creations to be suffering and sickness. Some seem to heed Horace’s advice to "delight and instruct" (or to create for one’s own delight) whilst others seem to confirm the saying "No pain, no gain" (or in this case, "No pain, no poems").

Not all authors of a theoretical or artistic work ascribe to one of these two opposing opinions regarding personal circumstances and, in particular, the moods that would stimulate their creativity and there are many who even reject the approach to the problem in those terms. But it is possible, however, to identify two clearly contending groups:

Of one school of thought would be those who consider that a state of well-being and satisfaction is the ideal one in order to be able to devote oneself to thought and artistic creation. This may seem the most obvious position since it coincides with the generally-held notion that culture is a luxury bestowed only on those whose most basic social, economic and psychological needs have already been met. However, the number of voices raised in protest against this viewpoint begs the question of whether this really is the majority view among creators.

Those of the opposing mindset maintain that discomfort, misery and anguish are the best fuel for creativity. Happiness is unproductive since it requires nothing whilst misery, on the other hand, would be a continuous spur to creative action, from this perspective. Creative work would serve as a means to expel the misfortune, thanks to one’s ability to express it creatively. At best, this intellectual or aesthetic expression of misery would enable us to overcome it, turning the manifestation of misfortune into a path leading towards well-being.

In his article "Duelo o placer de la escritura" (The Pain or Pleasure of Writing) (El País, 8 July 1986), the novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina argued both points of view. On the one hand, he recalled the beautiful words with which Cervantes described the ideal conditions for artistic creation: "Tranquility, peaceful surroundings, the pleasantness of the countryside, the serenity of the sky, the murmuring of the fountains and the stillness of the spirit in large measure turn even the most barren of muses fertile, offering new births to the world, filling it with wonder and contentment". On the other hand, Muñoz Molina broaches the idea of literary creation as the result of suffering, of the effort to flee from despair (and most definitely not as a gift from the sweet muses). Leaning towards the camp of those who think that human acts are more conditioned by historical circumstances than by the peculiarities of personal character, Muñoz Molina considered that these two outlooks would be characteristic of different times: "From Flaubert, perhaps from Baudelaire, the activity of literature, which was formerly a perk of laziness, shamelessly seeks the prestige of suffering and even of evil, which, on closer inspection, is a recent extravagance: among the Ancients, who admired Sophocles because he lived 90 years without a single day of unhappiness, the figure of Euripides, a hurdy and unhappy man mired in failure, was never emblematic of an artist but rather a mysterious exception".

The joyful laughter of the creator

The first viewpoint might be illustrated by the Nietzschean concept of creation. The creativity of the ‘higher self’ is, for this philosopher, a type of dance, a type of laughter, a type of game. The creator is the best representative of "great health": a being of joyful heart, of free spirit, light of foot. Fully convinced that "All good things laugh", the ‘higher self’ is able to laugh creatively because his theoretical works or his works of art are nothing more than the elaboration of that laughter with which he expresses his affirmation of the world; an affirmation that includes pleasure and pain, joy and misery and that is precisely why it is a tragic affirmation. For the Nietzschian creator, their work is the product of an unconditional affirmation of life, an affirmation that infuses them, that overflows from their eyes and hands; an affirmation understood as a desire for permanence, as a desire for eternity.

For Nietzsche, the antithesis of the creator is the priest – embodying the ultimate representation of all that is dirty, low and sick, of resentfulness triumphant over urges, of the weeping, wailing and gnashing of teeth, of the heavy heart, the gracelessness, of all that is sad, rigid and sterile. But included within this priestly archetype also belong all creators who feed off neurosis, anguish or pain and all those who require illness in order to be productive. From Nietzsche’s “great health”, it is noted with contempt that "Pain makes chickens and poets cackle".

This exciting concept of creativity, as proffered in some of Nietzsche’s theoretical texts, might seem to be called into question by the author’s own personal history: rejected by his university colleagues and by women like Lou Salomé, lonely, sick, isolated in rural boarding houses, writing books that nobody read, proud, misunderstood and ultimately committed to an asylum, Nietzsche does not seem to have been endowed with “great health”. And although all ad hominem arguments are usually considered dubious, the truth is that his life seems to be a denial of his joyful song. Unless we take it to mean that, as his works demonstrate, external personal circumstances failed to damage the energy of his laughter, the powerful dance of his thought, the great health of his spirit.

The artist's discomfort

The opposing approach has many advocates for whom creativity is nothing other than the philosopher’s stone, capable of turning suffering into gold. Art would be a happy encounter between anguish and the ability to express it beautifully. It would be elevated to the category of an author who, enduring the suffering produced by life’s difficulties, was able to do something of note with it. In this sense, neurosis would be the best resource of a fertile spirit, because, as in the words Borges put into his protagonist's mouth in “The Poet testifies to his Fame” - "the tools of my trade are humiliation and anguish".

There have been many artists who found a cause-and-effect relationship between misfortune and creation. "Ideas are substitutes for sorrows," said Marcel Proust. And Franz Schubert said that "Pain sharpens the spirit and makes the soul stronger". However, it is clear that pain can only have a toning effect if its nature, its intensity and the personality of the sufferer result in a fruitful response and not a sterile collapse. There can then arise an opposition between one pain that strengthens and another that sterilizes. Some think that it is a case of degrees: moderate pain would stimulate us, while excessive pain would paralyze us. As Émile Cioran has posited: "Great disasters offer up nothing, neither in the literary nor in the religious field. Only middling misfortunes are fruitful, because they can be, because they are a starting point, whilst a hell too perfect is almost as sterile as paradise".

Once the idea had been established that suffering was the source of creativity, its most ardent supporters began to draw conclusions. If discomfort is productive then everything that contributes to well-being probably has sterilizing side effects. For this reason, when a friend of the painter Edward Munch recommended he try to rid himself of the conflicts that were torturing him, he replied without hesitation: "They belong to me and to my art. They are part of me; if I were to remove them, it would harm my work. I want to hold on to these sufferings". And likewise, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke felt obliged to respond to an invitation of this kind: the aforementioned Lou Andreas Salomé, enthused by the work of Freud, recommended Rilke begin psychoanalysis in order to destroy the demons tormenting him. With suspicion akin to that of Munch, Rilke rejected the advice arguing that if psychoanalysis were able to wipe out his demons, it would also be able to destroy his angels. And then one is on the slippery slope to psychotherapists being sought out by authors with writers’ block, has-been painters and musicians in crisis who, having observed a clear relief from their neurotic troubles and an improvement of their mood but an impoverishment of their work, then demanded an urgent antidote against this cure.

There have also been authors who came to a reverse reasoning, stating that if pain and anguish are the stimuli for productivity, it is logical to think that pleasure and satisfaction are an obstacle to intellectual or artistic work. Borges, for example, recalls that "in a perfected paraphrasing of Boswell, Hudson references that many times throughout his life he had undertaken the study of metaphysics only for it to be always interrupted by happiness". If happiness is an obstacle to the study of metaphysics then simple pleasure can also be fatal for those faced with literary creation. Some have come up with an arithmetic formula for pleasures and creations according to which plus one pleasure equals minus one creation. And this is how one can interpret Balzac’s, albeit tongue-in-cheek, assertion that: "Every woman you sleep with is a novel you won’t write".

Along these lines, although with another type of argumentation, would be Freud’s stance: the artist would initially be so frustrated as to be bordering on neurosis. Like every other dissatisfied person, they would seek refuge in fantasies to compensate for their unfulfilled desires. What would allow them a release from frustration would be their ability to give expression to these fantasies and make them communicable by means of successful formal elaboration. Thanks to that skill, the secret imaginations of an introvert would potentially become works of art, able to provide pleasure to others and, as a consequence, able to provide its creator with success and with it the means to gratify their desires. The painful circle set in motion by dissatisfaction would thus be happily closed.

This Freudian approach could lead to the idea that in the artist’s past there would be someone (often a child) rejected and isolated by all others, or who at the very least would have the impression of being so. The psychogenesis of artistic creation would be linked to the need to overcome this state of loneliness, bitterness and lack of affection in which one’s character would harden and one’s intelligence, spirit and productivity sharpen. The suffering of the marginalized person would lead them to develop the qualities with which they will eventually achieve recognition from others, reunion and reconciliation with others and satisfaction through others. But from this odd theory, it seems to be being deduced once again that the consequences of a creator’s triumph would be the end of their creativity, that their success would essentially be castrating. And, although there are cases that confirm this idea, there are many others that refute it.

Creativity despite the bad, not thanks to it

In a lecture at the Madrid Circle of Fine Arts on 15 October 1987, the renowned English novelist Julian Barnes made some harsh criticisms of those who believe that suffering, illness and vice may be the origin of artistic creation. He instead vindicated the health of the artist in the face of the usual apologies for "the artists’ curse".

Barnes recalled that, for years, Flaubert collected newspaper clippings, quotes from articles or books and other similar materials that served as documentation. One of the folders in which he filed these was entitled "The stupidity of critics".

Among the texts he had kept there, Barnes found one about George Sand that seemed to him, effectively, "one of the most stupid criticisms that I have ever had the pleasure of reading". It attempts to explain the writer’s hostility to the family and to traditional, societal norms based on the fact that "George Sand smokes cigarettes all day, and George Sand is a woman!". Barnes commented that "George Sand’s cigarettes may have been responsible for many things, from an unpleasant smell in the salon to the cancer that killed her. But, as far as her opinions are concerned, the functioning of cause and effect is exactly the opposite of what the critic supposed. It was her opinions about women’s rights that led her to smoke, not smoking that shaped her opinions".

Barnes' criticism thus calls out all attempts to look for the origin of artistic creativity in factors that are ostensibly pathological and divorced from the talent and efforts of the artist: "At one time, doctors and philosophers would look for the location of the soul in human organs like the heart, the pituitary gland or wherever. Today we tend to locate genius in illness".

"What I attack, or at least what I am sceptical about, is this reductionist approach, the idea that the life of a writer or a painter can be explained in terms of a malady, a defect, a neurosis, of an incidence of sexual trauma in childhood or of smoking cigarettes. It is, incidentally, a trend that has been growing in the 20th century, partly, I suspect, due to the influence of psychoanalysis".

Barnes complains that, having published (by then) four novels, he had had to give several hundred interviews, leading him to ponder as to the reason for so many questions. "Perhaps interviewers are looking for that secret source of pain that would explain everything. But I can’t help them, I don’t think there’s anything to explain or at the very least I think my work is better explained in terms of my own work".

Among the many examples with which Barnes supports his position, he singles out a question that was posed to Gabriel García Marquez about whether the effusion of imagination and fantasy found in his books comes partly from pharmacological stimulants. Barnes acknowledges García Marquez’s right to show the interviewer the door but is glad that he gave the following answer instead: "Bad readers ask me if I take drugs when I write my books; but that just shows that they know nothing about either literature or drugs. To be a good writer, you have to be totally lucid at each and every moment and also be in good health".

After refuting, with historical and logical arguments, the theory that El Greco’s style stemmed from his hypothetical astigmatism, Barnes formulates his thesis in emphatic terms: "I am not saying that no painter has ever suffered from a sight disorder, nor am I saying that writers never smoke, drink alcohol, take drugs, suffer from diseases or behave neurotically. What I am saying is that they work despite all of this and not because of it. This century, we have almost made it orthodoxy that the artist is neurotic, sick or psychologically unbalanced. Of course, there are writers and artists who are paranoid but, in general, good writers and good painters rely on their ability to work really hard, their concentration and constant editing and revision until a certain perfection is achieved. And these are things that, in turn, depend on good health and a clean, clear mind".

Creativity notwithstanding the creator’s disposition

There is, therefore, a great diversity of opinion, reflecting very different and even exact opposite personal experiences. Finding an external point of reference to confirm or refute one or all others is no easy task. Some seriously defend the idea that sickness, misery and anguish, which turn the existence of the mediocre into pure torment, are instead, for creative minds, the stimulus and the essential instrument of their genius. Others argue that, for both an artist and a modest civil servant, malaise is merely an obstacle and a burden on one’s working or personal life.

There remains the option of rejecting the approach to the problem and criticizing the alternative on which revised opinions are based. There could be, at least in many cases, a separation between an artist’s work and their body or mind.

Assigning creativity its own autonomous character would lead one to think that works of art (or speculative constructions) cannot be reduced to the natural hazards of biology, to the disorders of the body or to the moods of the soul. But it is also possible to see in its genesis a total expression of the artist who, through amazing - and mysterious - mental mechanisms is able to transform what happens in the depths of his organism - and his mind - into an object of intellectual or aesthetic value. This alternative is so real that from it have derived two opposing ways of understanding aesthetics: the formalist and the psychobiographical. Neither is without merit and both have produced, in the hands of different critics, brilliant interpretations and utter nonsense.

José Lázaro

Professor of Medical Humanities, Department of Psychiatry, Universidad Autónoma of Madrid

Author: Vías paralelas. Vargas Llosa y Savater: un ensayo dialogado (Parallel Paths. Vargas Llosa and Savater: an essay in dialogues)

Translation from the original Dolor y goze en la creatividad in Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- The Pleasure and Pain of Creativity - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

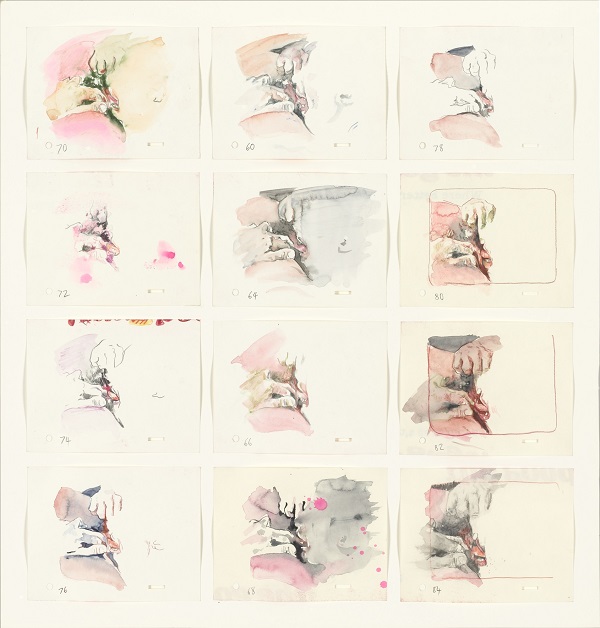

To contemplate a painting by Cecily Brown is to experience something vital, especially as regards the massive canvasses she churned out feverishly during the early years. Their surfaces manifest an intense vacuous horror, where a profusion of colours and brushstrokes reveal bodies twisted in passion or revulsion, fairytale characters, nudes, fruits, trees or, even, just lines of expression and vibrant colours that are a masterclass in composition.

Painting As A Reflection Of Passions

Cecily Brown

To contemplate a painting by Cecily Brown is to experience something vital, especially as regards the massive canvasses she churned out feverishly during the early years. Their surfaces manifest an intense vacuous horror, where a profusion of colours and brushstrokes reveal bodies twisted in passion or revulsion, fairytale characters, nudes, fruits, trees or, even, just lines of expression and vibrant colours that are a masterclass in composition. Although the influence of her friend and mentor Francis Bacon is evident in all her works (along with that of the classical and neoclassical masters), Brown still manages to escape the precarious stereotype of "women’s art" and forge her way into the field of 20th and 21st century abstractionism with a powerful sexuality and uncommon violence. Today, after struggling to make a name for herself on the New York art scene whilst working as a waitress, she is considered one of the key figures in contemporary painting. Her work expresses talent, energy and intellectual power, drawing the viewer into a complex web of brushwork, colours and intermingled shapes where each stroke has its place.

Girl on a swing (2005)

A childhood impacted by art (and Francis Bacon)

Untitled (1996)

Cecily Brown was born in Surrey, England in 1969 to a novelist mother and an art critic and curator father. She lived a bohemian childhood submerged in art, intellectualism and creative freedom - a family environment that would have a decisive influence on her future artistic vocation. In her own words, she decided to become an artist at the age of three, something that probably had not a little to do with her early contact with the British painter and draughtsman Francis Bacon, one of the most important figures in modern art and one whose paintings are among the most sought-after today. Bacon and Brown’s bonds of friendship would be maintained over time and exert a clear and profound influence on her own art. Likewise, the decisive impact of her mother’s creativity, work ethic and energy would also play a key part in the development of Brown’s personality, budding creative talent and work.

Adolescence and young adulthood in London – the difficult years

Untitled (Kebab) and Humpty Dumpty (1993)

At age 16, Brown left mainstream school to focus on a future in art. After two years at the Surrey School of Art and Design, she moved to London and studied drawing and engraving, as well as training under the tutelage of the painter Maggi Hambling. During that time and in order to survive in the big city, she worked as a cleaner - something she would continue to do until achieving definitive recognition. Paradoxically, her friendship with Francis Bacon continued and deepened due to their mutual fondness for visiting local art exhibitions. In 1993, Brown graduated with honours from the Slade School of Fine Art and won First Prize in the National Competition for British Art Students. Embracing the influence of Bacon's pictorial imaginary, she distanced herself from the London art scene of the 90s - a world of installations, large-scale or site-specific works and multimedia creations, among other contemporary disciplines. This commitment to a traditional style of painting would prevent her from making a name for herself in what was the capital’s highly dynamic art scene.

Fleeing to New York and the first signs of success

Four Letter Heaven (screenshots from animated short, 1995)

Tired of achieving no recognition in London, Brown moved to New York in search of new horizons. In 1995, she arrived in the city whose sights and lights had dazzled her on a previous trip and decided to move away from painting in order to explore other formats. This was when she created “Four Letter Heaven”, an animated short with erotic overtones using mixed media, which went on to win an award at the Telluride Festival. At that time, a still young Brown was working as a waitress and suffering severe economic hardship. She went back to working on canvas, painting in a compulsive and feverish way in her Manhattan studio and it was then that she began to create her emblematic large-scale works: paintings in which brushstroke and colour generate scenes of chaos, midway between abstraction and figuration and in which violence and sex always make an appearance.

Spree (1999)

From the moment of her solo exhibition organised by the Deitch Projects gallery in 1997, Brown's rise on the New York art scene was unstoppable, with exhibitions of her work continuing throughout the decade and receiving total acceptance from critics and the public alike. Aged just 29, one of the world’s most prestigious art galleries, the Gagosian in New York, decided to represent her and include her work in its catalogue. She continued to paint almost obsessively in the new studio she shared with Sean Landers, a fellow painter and her partner at the time. Success, however, did not bring her any sense of satisfaction and those days and years would become one long and intense succession of parties, alcohol, boyfriends and art. In later years, Brown would admit that she felt "forced" to play the role of "tormented genius", leading a lifestyle according to what seemed to be demanded then on New York’s art scene.

“life, death and the kitchen sink”

Black Painting (2002)

Brown has never hidden her admiration for classical masters and the avant-garde. From Goya to the American abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning, her canvases reflect clear influences from previous artistic schools: Goya's Black Paintings and Kooning's Monsters, among others. Brown’s series of Black Paintings took their inspiration and made it her own, with powerful brushstrokes, chaos and an intense, disturbing sexuality as new additions.

Untitled (2011)

While Brown has retained her style and creative identity over the decades, it is clear that in recent years her art has undergone an interesting evolution. After her 15-year collaboration with the Gagosian Gallery ended, her paintings began to take on a smaller size and an obvious change in themes - canvases where violence, chaos and human sexuality seemed to burst onto the canvas through colour and where gesture made way for less powerful themes. As Brown recently remarked, "What interests me now is life, death and the kitchen sink." In addition to working on canvas or panel, Brown has also created installations for multiple art spaces and has collaborated on the creation of murals.

Creation of a mural in Buffalo (USA) by the city's community of artists and art students, in collaboration with Cecily Brown

Exhibitions

Brown has seen her work exhibited in some of the most important museums and galleries in the world. In 2014, the Gagosian Gallery organized a large exhibition of her work so far that decade. Her work has also been recognized in multiple exhibitions and retrospectives, such as those held by the MACRO in Rome (2003) and the Queen Sofía National Museum of Art in Madrid (2004). Below are highlighted some of the most recent exhibitions of her work around the world.

Cecily Brown: Rehearsal (2016)

In New York, THE DRAWING CENTER is one of SoHo’s benchmark art institutions. 2016 saw its first ever Cecily Brown retrospective exhibition, with eighty drawings and sketches accompanied by several works in mixed media showcasing the relationship between both disciplines.

Cecily Brown. Paula Cooper Gallery (2020)

In 2020, another highly influential and prestigious venue, the Paula Cooper Gallery, exhibited a series of works Brown produced during the Covid-19 lockdown. The paintings are inspired by the Flemish Master Frans Snyders and depict tables stacked with hunting paraphernalia among which multiple vague human shapes that can just about be seen, some in openly erotic poses.

Cecily Brown at Blenheim Palace (2020-21)

Brown was the first person to feature in a major monographic exhibition here with works from her New York period, at the request of Blenheim Palace. In the video, Brown explains how her creative process works and how the Palace environment was an inspiration.

Books

Cecily Brown: Days of Heaven. StephanSchmidt-Wulffen. 2001

The presence of an intense eroticism, bordering on pornography, is common in Brown’s work. She explains: "I use [pornographic] material to study the body. With it I am interested in the emotional content of these models”. Seen from a certain distance, the dots, colours and brushstrokes of her paintings become naked bodies portraying erotic scenes. The exhibition “Days of Heaven” allowed visitors an insight into this side of the artist's work, as reflected in the catalogue of the same title.

Cecily Brown: The Sleep Around and the Lost and Found. Terry R. Myers. 2016

This catalogue features all of the works brought together for the exhibition of the same title, organized by the Berlin Centre for Contemporary Art in 2015. Its pages gleam with large full-page colour reproductions and also showcases the installation that the artist created for the occasion. The pictures are accompanied by an exhaustive essay on Brown's work, written by art critic, professor and curator Terry R. Myers.

Cecily Brown: Shipwreck Drawings. 2017

The violence that is so commonly depicted in Brown's painting by means of the human body shifts here to instead be portrayed through shipwreck imagery. Rather than painting on canvas, she chooses drawings to capture intense scenes of nautical disasters, by dint of which she highlights the tensions between the past and the present. In these charcoal, pastel, watercolour and ink drawings, she is clearly inspired by the work of Delacroix and, more so, by Géricault's well-known “The Raft of the Medusa”.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Cecily Brown: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Pedro García Cuartango

Spinoza held that the world is the expression of a divine substance that determines the laws of physics and human actions. I could not agree more. If I had to take one book with me to a desert island, it would be Spinoza's “Ethics”. When I first read the work as a young man, I believed in a universe enlightened by divine wisdom.

Spinoza held that the world is the expression of a divine substance that determines the laws of physics and human actions.

I could not agree more. If I had to take one book with me to a desert island, it would be Spinoza's “Ethics”. When I first read the work as a young man, I believed in a universe enlightened by divine wisdom. The philosopher’s words were like a balm to heal the wound caused by reality - that God did not just create what our eyes perceive but also that everything in existence is imbued with his essence. And not in a figurative or idealistic sense but a material one because, as he concludes, the attributes of The Almighty manifest themselves in the world and all that we see, think or touch is an extention of divinity. There is nothing outside of God, not even evil.

Spinoza did not have an easy life. He was born in Amsterdam in 1632 into a Jewish family that had probably fled the Inquisition in Spain. At a young age, he was excommunicated as a heretic and, despite the pleas of his relatives and friends, he never recanted. He was slandered and branded a heathen but never once uttered a word of reproach about this to his fellow men. He lived to be just 44 years old and died alone after a life of earning his living as a lens polisher. His final years were spent in The Hague writing his “Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order”.

That title may well surprise us today but Spinoza believed that geometry was a science whose postulates could be demonstrated with certainty. He wanted the axioms, propositions, corollaries and scholia of his work to have the same logical consistency as lines and angles projected onto a plane. For him, geometry was the most perfect embodiment of rationality.

It was Spinoza who affirmed that "the desire of Man is to persevere in his own being", since he understood that desire is the wish for self-knowledge and, beyond this, human nature is an expression of the infinite goodness of God, who is omniscient and eternal.

There are few other references to Man in “Ethics”, throughout which humanity is curiously absent. Spinoza reflects on substance, attributes, inclinations and God, but says almost nothing about the human being. It took me some time to understand that the concept of Man is a simple extension of the substance that, according to proposition VIII, is "necessarily infinite". What is “real” is a unique substance that permeates everything that exists and in which all things participate. But what is “real” is plural because it is endowed with the infinite attributes and inclinations of substance. As our understanding of it is limited, we are unable to understand the infinity of the Universe.

We should not make the mistake of confusing substance with physical matter in Spinoza's philosophy because the existing world is nothing more than the unfolding of God in history, a notion that does not fail to offer a misleading temporal perspective because everything begins and ends in a Supreme Being who comprises the beginning and the end of all things. “Whatsoever is, is in God, and without God nothing can be, or be conceived”, he says in proposition XV.

What this means is that we carry out the will of God even when we do evil. Sin is still an insignificant deviation in the divine design and, in any case, it is an action produced by ignorance of the benevolent essence of the Almighty. The good and the bad, the noble and the base, the generous and the selfish are subsumed in the evolution of a substance that, essentially, denies free will.

Spinoza did not believe in the moral norms dictated by rabbis and Lutheran pastors. He thought, as did Kant, in every man’s autonomy to act according to his conscience. This implied a radical defence of freedom of thought in a Europe that had just suffered a bitter and bloody religious war. But by the same token, he maintained, in somewhat of a contradiction, that freedom consists in our adhering to the laws that reason dictates and that lead to virtue.

Excomulgado Spinoza. Samuel Hirszenberg,1907

If Descartes distinguished between the spirit and the body, which forms part of the res extensa, Spinoza breaks that dualism by affirming that Man and God are the same thing or, more precisely, that we are imperfect extensions of a superior reality. The soul, however, is immortal and imperishable to the extent that it emanates from the divine substance, which brings it very close to pantheism, as scholars of “Ethics” have underlined.

Beyond its coherence, the work of Spinoza, the most heterodox thinker of his time, has a beauty that captivates those who delve into it. He always lived according to his principles, renouncing fame and fortune and devoting his efforts to formulating a system that attempted to answer important questions about existence itself. His “Ethics” continues to present a challenge for all those still willing to take the risk of thinking.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

SPINOZA: A COMPLETE GUIDE TO LIFE

- Spinoza: All Is God and God Is All - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Florence, during the first decades of the fifteenth century, was the axis around which the world turned. In among its twenty neighbourhoods with their gonfaloniers, their streets and palaces, their churches and houses, Alberti was writing his treatise “On Painting”, Masaccio had painted the Brancacci Chapel frescoes and his Holy Trinity adorned Santa Maria Novella church, Ghiberti completed the North Door of the Baptistery and Brunelleschi crowned Florence cathedral with a dome which, using never-before-seen techniques, he made to float in its enormity above the Santa Maria del Fiore apse.

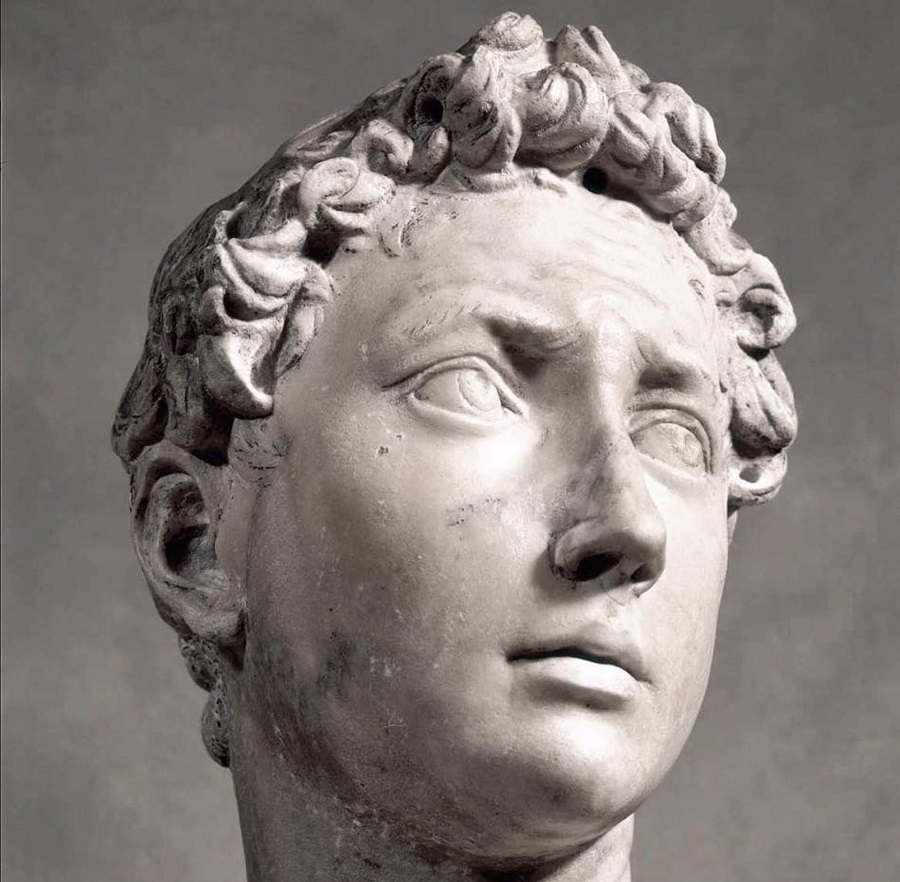

Donatello, David (detail, (1435-1440), National Museum of Bargello, Florence

Florence, during the first decades of the fifteenth century, was the axis around which the world turned. In among its twenty neighbourhoods with their gonfaloniers, their streets and palaces, their churches and houses, Alberti was writing his treatise “On Painting”, Masaccio had painted the Brancacci Chapel frescoes and his Holy Trinity adorned Santa Maria Novella church, Ghiberti completed the North Door of the Baptistery and Brunelleschi crowned Florence cathedral with a dome which, using never-before-seen techniques, he made to float in its enormity above the Santa Maria del Fiore apse. The year was 1436.

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

Meanwhile, in his small workshop on the banks of the Arno, Donatello sculpted the relief of the plinth of Saint George of Orsanmichele. His mastery was to forever revolutionize the principles of sculpture. Six hundred years later, Florence returns light to a world full of darkness with one hundred and thirty works on display throughout the Strozzi Palace and the National Museum of Bargello, in a historic and unrepeatable tribute to its sculptor son. The exhibition carries the name: Donatello, the Renaissance.

Donatello, Horse's Head (1456), National Museum of Archeology, Naples

Donato di Niccolo di Betto Bardi - Donatello being the nickname given him by his family - was born in Florence in 1386. The Donatello family lived on the south bank of the Arno river and were members, through Niccolò (father) and Betto (grandfather), of the wool carders’ guild, one of the most influential in Florentine society at the time. From an early age, he worked with a local goldsmith through whom he discovered metal alloys, while also learning how to sculpt from the stone carvers working on the construction of the Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral. In 1403, he entered the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti, a sculptor in bronze who had, the year before, won a competition to create the Gates of Paradise for the Baptistery. Donatello had collaborated with him and had since become friends with Filippo Brunelleschi with whom he travelled to Rome. Little is known about this trip except that, by aiding in the excavation of the ruins of the ancient Empire, Donatello acquired a profound understanding of the ornamentation and classical forms of Roman sculpture, movement, fabric and gesture. This apprenticeship, together with the tutorship of Ghiberti - the greatest exponent of an international Gothic style typified by smooth, curved lines - had a marked impact on the sculptor's style which would evolve into the life-size marble "David" that kickstarts the Florence exhibition today.

Donatello, David (1408-1416) National Museum of Bargello, Florence

The first room of the Strozzi Palace is breathtaking. "David" (1408), centre stage, was carved by Donatello in his early twenties. He had received a commission for a monumental figure of the King of Judea to form part of a row of statues to act as guardians of the Duomo, anchored atop the buttresses as if miraculously silhouetted against the sky. The work was completed by the end of the same year with all that remained being to lift it into place. As soon as the scaffolding was erected, however, it was found to be too small to create the desired impact. At that elevation, the six-foot high prophet statues looked insignificant. For this reason, the David was positioned in a new, unexpected and more worthy location. The figure of the young biblical hero, also one of the symbols of the Florentine Republic, was purchased by the government for its headquarters in the Palazzo della Signoria. Standing him on a pedestal at ground level proved to better highlight the slight twisting of the torso, the flexing of the leg and an oblique, frowning stare gazing into space. In this exhibition room, the enormous head of Goliath with a rock embedded in his forehead at David's feet is at eye level. And on looking up, we see two chilling crucifixes in painted wood flanking the statue of David. On the left, Donatello’s (1408) and on the right, Brunelleschi’s (1410).

First exhibition room: Donatello's "David" (1408)(centre), Donatello's Crucifix from the Basílica of Santa Croce, Florence (1408) (left) and Brunelleschi's Crucifix from Santa Maria Novella, Florence (1410) (right)

The sculptor’s outlook was maturing. His work was moving away from the Gothic tradition and towards a more personal, more solid style. The years from 1411 to 1413 saw a radical shift in his art that broke free with transformative force. Brunelleschi and Donatello spent hours observing the multiple panoramas and buildings of Florence. Brunelleschi was beginning to understand how geometric shapes underlie the relationship between humans and their environment. Donatello would convey these conclusions through the medium of sculpture. Both artists were luminaries in the discovery of perspective.

Donatello, Saint George (detail), c.1415-17, National Museum of Bargello, Florence

Donatello now began creating a brand new way of sculpting that he would apply for the first time to the “St George and the Dragon” in the predella panel of the Armaioli tabernacle in Orsanmichele Church and which he chiselled out using “soft stiacciato” (“flattened out”), as Vasari termed it. This technique involved the shallow carving of a relief whose depth and surface projection gradually increased towards the foreground where the figures and objects are closest and the most prominent. In the background, the shapes are just a few millimetres deep, hardly more than a slight incision.

From then onwards, he introduced the “stiacciato” method to his reliefs which were admired throughout Florence and paved the way for other sculptors, inlayers and painters. Brunelleschi's laws of perspective, applied using this technique, allowed the sculptor to virtually and optically multiply space with a hitherto unknown sensory illusion of reality, creating a revelation between the viewer and the work.

Donatello, Saint George and the Dragon (1416-1417), National Museum of Bargello, Florence

In the third room of the Strozzi Palace, behind the “Attis Amorino”, we find the bas-relief of “The Pazzi Madonna” (1422), chosen to be the poster for the exhibition. It is one of the most emotive interpretations of the Madonna and Child of the Renaissance. The mother, with a profile and veil reminiscent of Ancient Greece, holds her son in her arms and brushes her face against his in a gesture of intense sweetness. Her eyes, in which the tragic events at Calvary can be read, are fixed on those of the child she embraces with hands seemingly desperate to protect him. The child, oblivious, smiles showing his milk teeth and clutches his mother’s veil with total naturalness.

Donatello, Madonna Pazzi (1422), Staatliche Museum, Berlin

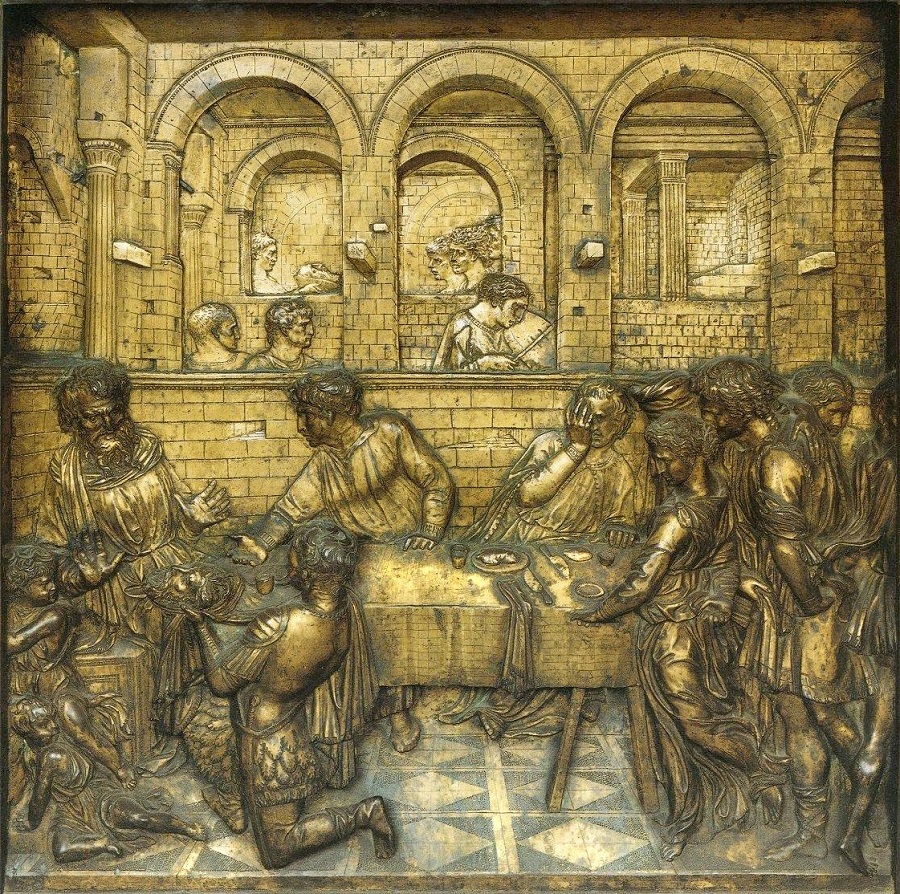

Also in this room is a small golden panel of brilliant virtuosity – a relief depicting “The Feast of Herod” (1423) from the Baptistery of Sienna. Donatello designed here, as never before, a scene with a Brunelleschian perspective in which the arrangement of the figures and the narration take place in four gradations of depth on a bronze plate. We can see, on approaching the work from the side, that it is no more than a couple of fingers thick but within those few centimetres, a whole story is taking place beneath the arches of a palace’s myriad rooms. In a foreground full of details, characters and gestures, Herod holds out his arms in rejection while a kneeling servant presents him with the head of John the Baptist on a platter. The rest of the characters allow the sculptor to portray an array of hairstyles, drapery, hand movements, musical instruments and terrified children fleeing the scene via its frame.

Donatello, The Feast of Herod (1423-1427), Baptistery of San Giovanni, Sienna

The Bargello Palace was built in 1255 as the seat of the Florence Consistory and was later used as a prison. The Greater Council Room is presided over by three Donatello works – “Saint George”, set in a high niche where he appears solemn and distant, his torso turned slightly and his frown focussed somewhere in the distance; “Marzocco”, the emblematic lion of the city and the bronze “David” that presides over this grand Gothic room.

Donatello Room, National Museum of Bargello, Florence

This “David” was a statue designed to be raised on a column and viewed from below. When Donatello thought of reviving this motif, the idea of a column, of bronze metal and of a nude figure became paramount. His choice was of a noble biblical character, prototype of Christ and emblematic shepherd of the Florentina libertas. Donatello deliberately distorted his sculpture’s body in order for it to be perfectly proportioned when seen at this level. The victor thus floated above Goliath's severed head while he gazed vainly at the crowd.

Donatello, David Victorious (1435-1440), National Museum of Bargello, Florence

“David” was a statue designed to be raised on a column and viewed from below. When Donatello thought of reviving this motif, the idea of this column, of bronze metal and of a nude figure became paramount. His choice was of a noble biblical character, prototype of Christ and emblematic shepherd of the Florentina libertas. Donatello deliberately distorted his sculpture’s body in order for it to be perfectly proportioned when seen from eye level. The victor thus floated above Goliath's severed head while he gazed vainly at the crowd.

“David”, cast for Cosimo de’ Medici, symbolizes among other things the relationship between the sculptor and the illustrious Florentine family. The ambition of Cosimo and Lorenzo de' Medici, fulfilled in 1434 with the return of the brothers from exile and materialized in the commissioning of a work that symbolized power. At first, this “David” presided over the main entrance of the “Casa Vechia” but was later transferred to the new palace on the Vía Larga. It was the first in-the-round nude figure sculpted in Italy since the Roman Empire. The adolescent, a disdainful ephebe whose fine face is framed by cascades of curls, wears a picturesque hat and a dismissive smile whilst his posture, in slight contrapposto, is an audacity of balance.

All decisions concerning “David” were always made with the agreement of Cosimo the Elder, Donatello's main supporter and patron. Vasari tells us that Donatello died "in his little house on the Via del Cocomero", near the site now occupied by the Galleria dell'Accademia. By then he had already completed what would be his very last work, the impressive pulpits of San Lorenzo, the church linked to the Medici. His workshop was located next to the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore. He had previously moved too many times to mention here but his final resting place has never changed. It is inside the crypt of San Lorenzo, just a few metres from the tomb of Cosimo the Elder.

Donatello, Pulpits of San Lorenzo (1460), Florence

Donatello, the Renaissance

Strozzi Palace and National Museum of Bargello

Via del Proconsolo 4, Florence

Curator: Francesco Caglioti

19 March - 31 July 2022

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

It must have been a dazzling sight to behold when the waters of the Nile flooded the lowlands of Ancient Egypt. The ground disappearing, the ditches filling in, villages emerging as if tiny islands and the swelling of the river setting the rhythm of time. There are some 1,000 kilometres between Aswan and the Mediterranean and covering three-quarters of this distance, Upper Egypt is a furrow hollowed into the desert.

Lintel of the temple of King Amenemhat III (detail), Egypt, 12th Dynasty, 1855-1908 BC, British Museum

It must have been a dazzling sight to behold when the waters of the Nile flooded the lowlands of Ancient Egypt. The ground disappearing, the ditches filling in, villages emerging as if tiny islands and the swelling of the river setting the rhythm of time. There are some 1,000 kilometres between Aswan and the Mediterranean and covering three-quarters of this distance, Upper Egypt is a furrow hollowed into the desert. The rest is made up of the delta, so called because the Greeks recognized in its triangular shape the fourth letter of their alphabet.

Around 5,200 years ago, some of the peoples living on the banks of the Nile among the papyrus plants and palm trees must have felt the need to reflect everything around them in writing and chiselled out the first ever hieroglyphs in history, in some or other pieces of stone. The oldest we know of date from 3,250 BC and together with cuneiform script are the earliest forms of human writing. How many thousands of years must human beings have been interacting without feeling the need to write anything down until then?

Lintel of the temple of King Amenemhat III, Egypt, 12th Dynasty, 1855-1908 BC, British Museum

London, in early 2023, finds itself embroiled in the furore surrounding the recent appointment of yet another Prime Minister and the upcoming coronation of Charles III at Westminster Abbey. However, one would be hard pressed to hear a pin drop in any of the galleries of the British Museum "Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt", a display featuring 240 objects from national and international collections in celebratation of the two hundred year anniversary of the decipherment of the Rosetta stone.

Exhibition room at the British Museum during "Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt"

The exhibition, dimly-lit and its black walls painted over with silver hieroglyphics, accentuates the sensation of being inside a pyramid. At its conclusion, in the final room, scenes of the banks of the Nile are projected in the round - its feluccas and palm trees, its temples and obelisks, its pyramids and birds in flight and behind them, the whole sea of the desert.

Fragment from the Book Of The Dead of Nedjmet, Egypt, 11th Dynasty, c. 1069 BC, British Museum, London

Sarcophagus of Hapmen, Cairo, XXVI Dynasty, c. 600 BC, British Museum, London

The display cases of the exhibition contain fascinating objects such as Champollion’s and Thomas Young’s own personal notes, four canopic vases preserving the organs of the deceased, the bandage of the Mummy of Aberuait and the 3,000-year-old Book of the Dead of Queen Nedjmet. Papyrus grew abundantly on the fertile, marshy banks of the Nile - a plant, whose name derives from the Greek word meaning "royal", raises its umbrella head on a stem that can reach up to six metres in height. Their stalks were used for shipbuilding, their fibres served to make ropes, mats, sails, baskets and sandals while its central pith created the papyrus on which to write.

Mummy of Bakentenhor, 12th Dynasty, 945-715 BC, Great North Museum

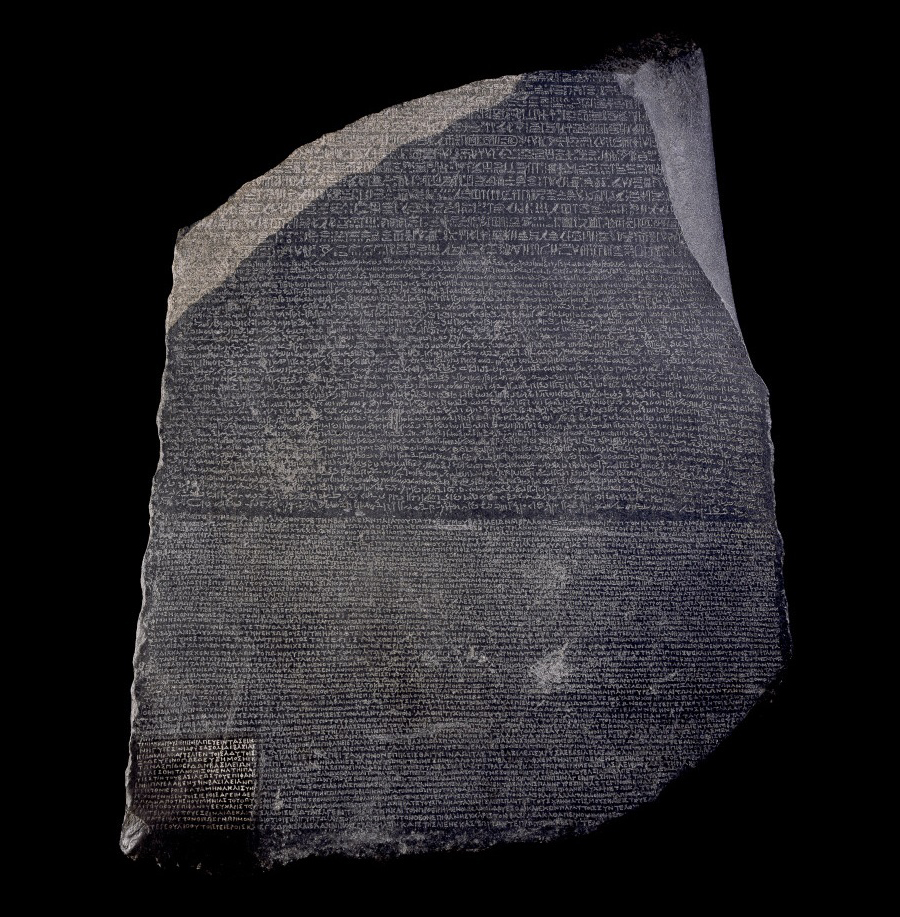

Nevertheless, the centrepiece of the exhibition is the Rosetta Stone, spot-lit as if by a magic beam, as if it were kryptonite. This fragment of an ancient stele is synonymous with the hieroglyphs that covered statues, monuments and papyri in Ancient Egypt. Its pictorial-style script was closely linked to Egyptian culture but although it was never used elsewhere, it was imitated throughout the kingdoms of ancient Sudan and appears to have inspired the Proto-Sinaitic script, in turn a possible distant ancestor of the modern alphabet.

Rosetta Stone, 196 BC, Ptolemaic Dynasty, British Museum, London

The first pages of Jean-François Champollion’s book, “Egyptian Pantheon”, open with a description of Amun - a god in human form usually seated on a throne. His skin is blue and his beard is styled as the black appendage characteristic of male divinities. When this same appendage appears on coffins, it indicates the mummy of a male. Held in his left hand is a sceptre crowned with a bird's head and it is the sceptre common to all the male divinities of the Egyptian pantheon. In his right hand, he carries a cross, surmounted by an oval or handle-shaped loop - the symbol of divine life. He wears a tall double-plumed royal headdress. A long blue ribbon cascades down his back. It is an aesthetic so powerful it begs the question - if the 19th century was one of revivals, namely, the use of visual styles that consciously echo an earlier architectural era (this being the case of Pompeii and Pompeian styles, Gothic and Gothic Revival and Neoclassicism), what then is the reason why a taste as refined as that of Pharaonic Egypt was not also taken as inspiration for the decoration of future palaces, clothing, furniture or tableware?

Statue of an anonymous scribe, Egypt, 5th Dynasty, 2494-2345 BC, Louvre Museum

The story of the Rosetta Stone has an inexplicable force. In December 1797, Tipu Sultan of Mysore in India asked Napoleon for help in quelling the growing threat of British power in India. It was then that, in the margins of a book about the Great Turkish War, Napoleon wrote: "Through Egypt, we will invade India." Emboldened by victories in Italy but frustrated by his attempts to invade England, Napoleon landed in Alexandria on July 1, 1798 with an army of 40,000 men. He was accompanied by the Commission des Sciences et des Arts (Commission of the Sciences and Arts) that brought together the most brilliant French minds and that, in the spirit of the prevailing Enlightenment, was to investigate and map both ancient and modern Egypt.

In mid-July of 1799 and faced with an imminent attack by Ottoman naval forces wishing to avenge Napoleon's campaign in Syria, the French reinforced their coastal defences. In Rashid (Rosetta), a port city on the western bank of the Nile delta, the demolition of Fort St. Julien was ordered and a block of granodiorite stone appeared among the foundations, a fragment from an ancient Egyptian stele with a decree published in Memphis in the year 196 BC under the name of Pharaoh Ptolemy V. The decree appeared in three different scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphs at the top, Greek at the bottom and between the two an unknown inscription initially believed to be Syriac.

Its pivotal role in the decipherment of hieroglyphs was immediately recognized. It was dug out of the dust, cleaned, and the Greek section was translated. Afterwards, it was transported by boat up the Nile to the Cairo Institute where its discovery was announced on August 19, 1799. There, the first and most crucial task was to make exact duplicate copies of the texts. Two young Orientalists recognized the central inscription as Demotic, a cursive script of the Egyptian language that they had seen before on papyri and mummy bandages.

Copying by hand would have meant, in addition to the risk of human error, months of work. It was decided to clean the stone and to leave the water in the crevices, its surface was covered with ink and traced onto sheets of damp paper. Thus, on January 24, 1800, a reverse copy was created in black on white that could be read with a mirror or via a light source. In Paris 22, years later, Jean-François Champollion presented his discoveries on hieroglyphs to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Two weeks earlier and after exhausting and exhaustive research that had seriously affected his health, Champollion had succeeded in deciphering the names of Cleopatra, Ramses and Thutmose III and, therefore, the writing of the ancient Egyptians.

Medal commemorating Thomas Young, mid 20th century, British Museum, London

Over time, the understanding of hieroglyphs was lost as the culture of Ancient Egypt was swept away by waves of conquests and occupations. The Arab invasion of the 7th century brought Islam and with it both the Arabic language and a succession of rulers culminating in the rule of the Mamluks.

Today, the Rosetta Stone is the British Museum’s most visited piece, with the bicentenaries of its decipherment along with that of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb again stirring up one of the most contentious debates of recent times, namely, renewed calls for the restitution of artefacts and antiquities to their countries of origin. The disputes have resulted in some agreements being reached but each case is different and, for Western museums, some emblematic pieces are considered untouchable and will always be the Cultural Heritage of all humankind.

The reflections of Egyptologist Silvio Curto illustrate why that is: "What was established during the Pharaonic era was the concept of the supreme dignity of the human being and that must be returned to and perfected throughout history, from Socrates to Kant."

Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt

British Museum, London

Curator: Ilona Regulski

13 October 2022 - 19 February 2023

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Hieroglyphs : Shining A Light On Ancient Egypt - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Nicolas Berggruen (1961) is the founder and chairperson of Berggruen Holdings and the interdisciplinary think-tank, the Berggruen Institute, where scientists, economists, philosophers and artists from around the world engage and put forward proposals to tackle the 21st-century challenges facing humanity. Among the issues raised against the technifying, globalization and capitalist background of our time is that of how we see ourselves and recognize the other person in all their fullness from a moral perspective.

Nicolas Berggruen. Foto: Ernesto Agudo

Nicolas Berggruen (1961) is the founder and chairperson of Berggruen Holdings and the interdisciplinary think-tank, the Berggruen Institute, where scientists, economists, philosophers and artists from around the world engage and put forward proposals to tackle the 21st-century challenges facing humanity. Among the issues raised against the technifying, globalization and capitalist background of our time is that of how we see ourselves and recognize the other person in all their fullness from a moral perspective. On a plane beyond that of the spatial and temporal cultural relativism, Western and Eastern wisdom combine in his thought, which is articulated with practical proposals geared towards implementing good governance in a world undergoing profound transformations.

In 2010, his philanthropic conviction saw him make an important commitment to the Warren Buffet and Bill and Melinda Gates led initiative, “The Giving Pledge”: giving the major part of his wealth during his lifetime, through the Nicolas Berggruen Charitable Trust, to help solve some of the most pressing problems facing humanity. His passion for philosophy is readily attested to by his creation of the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture, comprising a million dollar donation to thinkers whose ideas and commitment help the world to progress in a more human fashion.

Co-author with Nathan Gardels of the book Intelligent Governance for the21st century, which was hailed by the Financial Times as one of the best books in 2012, he has just published, once again together with Gardels, his book Renovating Democracy (Nola Editores).

Could you start by pointing out the most serious problems affecting our Western democratic system in the age of globalization and digital capitalism?

To my mind, the good thing about democracy is that it gives everyone a voice and the bad thing is that it gives everyone a voice. In the past, we had a potentially more direct dynamic. We had dominant political parties and traditional media that were the editors or the filters who would be the intermediaries with the general public. With social media, this has disappeared because people, including politicians, talk directly to each other. This creates an incredibly dynamic environment. We could say super-democratic because everybody has access and everybody has a voice. This happens in advanced democracies like Spain and in places around the world where democracy is much more recent. It is actually a very liberating and wonderful thing, but at the same time, it all becomes very confusing because the traditional editors and filters are no longer present. On one side, it's an explosion of voices and a part of what democracy should be about. On the other side, that same explosion can lead to a wild situation in which it becomes harder to bring people together. As opposed to bringing people together, it can tear people apart. That is really the issue today.

So, how do you manage everyone's podium?

If we can bring all these people together to think about the issues, debate them, and ultimately vote on them in a reasoned way, then in the long term, it will be good for everyone. Another problem is the politicization of what should not be politicized, such as scientific issues like COVID, which is a health issue and should remain so. Scientists and relevant government offices should deal with certain things like health. There are two problems here: one, everything is politicized, and people don't want to listen to and trust health authorities, and two, in today's democratic world, there is less and less trust in government. This is a profound problem in the U.S., where trust in government has decreased, and it has become a vicious cycle because this lack of trust makes it more difficult for the government to function. This, in turn, makes it less attractive to work for governments, so you have less talent. A lack of talent means performance suffers, and when this happens, people like the government less, which makes sense. And it goes down and down from there. So democracy, in a way, is undermined from within. In short, what we have is a domino effect.

You highlight the impact of the information revolution and social networks on governance and how social problems are reduced to slogans that spread among those who think alike instead of using argumentation and dialogue to reach a consensus. Could you tell me more about your ideas in which the IT sector can help innovate today's democracy?

There are two aspects to this. One is that there should be innovation in governance, and the other is the management of social networks. In terms of innovation, the idea would be to have citizen forums debating different issues and then recommending their conclusions to voters, governments, and bureaucrats. The problem we see is that the most engaged people are the most vocal and not the majority. This is the problem with involving people digitally. On the social media side, the issue is that we need an editor. The question today is, who? To take an extreme example: in China, the government is the editor. We don't want that. In the West, the editors right now are the social media platforms - Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or Meta, for example. Since they are not necessarily the best editors, the question becomes, who is? Is it the government, and to what extent? Europe has regulated technology platforms, although this hasn't helped the much-needed editing process much. So, will the citizens themselves edit by getting involved in a different way? There have been similar phenomena in the past, and over time society has managed them. The solution will have to be a combination of government regulation to make information more transparent and, as the most popular publications are the ones that get the most attention, platform regulation to reduce the connection between popularity and distribution.

As a result, a polarization of representative democracies in the West has produced an institutional crisis leading to the emergence of populism and nationalism. How do you feel about this in Europe?

I think that, unfortunately, populism is on the rise. Northern Europe is more right-wing, and southern Europe is more left-wing, but it is a reaction in both cases. A reaction, I would say, born out of frustration, anxiety, and fear. Fear of the future, fear of change. We have had decades of globalization and technological advances. Advances go at a digital pace and are probably too fast for humans. People become fearful. They don't want to change, and they don't want anything new. They want to go back to what they consider to be a better and very often traditional past. So they react politically and adopt a very marked attitude towards the left or the right. It is an instinct of fear, and it is simplifying things because most people would like to believe in something that inspires them, that is quite simple, and allows change. Today's big problem is that the extremes, left and right, which are the edges of society, are hijacking the center. Even if we have ten or fifteen percent on the edges, they become so powerful and their voices so loud that the majority of the center is hijacked. People have always said that democracy is the tyranny of the majority, but what has happened and what is perverse is that, in many democracies, it is the tyranny of the minorities because their voices stand out more, not only in Europe but in all democracies.

Another of humanity's great challenges is reversing the climate crisis and the loss of biodiversity around the globe. The Berggruen Institute is working on this. Having seen the G20 Summit and COP26 recently take place, do you think we are in time?

We are late. And the planet doesn't wait, so I think we are super late. The question is, how do we deal with a planetary crisis that we are all, including governments, aware of? Look at COVID, we had a global health crisis, and nobody cooperated, every country for themselves, in essence. The same issue is happening with climate change. There is some cooperation and some action because governments and civil society are aware and afraid to the point where they are beginning to take action, but not enough. Market mechanisms such as carbon credits and taxes need to be adopted without a doubt, and there are technological advances that will help, but it's a gamble. Will they get there in time? We are gambling with the planet. I would say the political will is there in terms of intentions, but not necessarily action. We at the institute have been working on this for a long time. We are concerned with practical solutions. For example, we have a program that has been in place for some time between California and China. In the U.S., at least during the last administration, there was really no will at the Washington level to do anything, but at the state level, especially California, there has always been concern about climate or the environment. Nevertheless, you cannot only have climate action in the U.S.; you also need other big countries. Today's biggest polluter is China, so we need their participation alongside that of India and many others.

The Berggruen Institute also contributes through philosophy, art and technology to help us adapt to the speed of change affecting all dimensions of the human condition. Artificial Intelligence and Biotechnology are transforming the way we think of ourselves as human beings. What are your perspectives on this?

Some technologies such as artificial intelligence or gene editing will fundamentally, or potentially, transform the nature of humans. This may be the first time in history that humans can play God. We can self-transform. Through gene editing, we can transfer or change embryos, and we can change genetic lines. With AI, we will be able to potentially create other agents that are just as capable as us in certain areas or that augment our capabilities, and we can even combine the silicon base. So the problem is not only becoming more powerful. What is interesting, based on our experience, is that technologists show a very optimistic and very naïve attitude in which technology will solve everything and be good for everybody, but they don't look at the unintended consequences. We also see that the government lags way behind, especially in the U.S. They don't understand the technology. So what we have tried to do is to have an active dialogue between policymakers, scientists, technicians, companies that produce these things, economists, philosophers, and artists who all have totally different views. The idea is simple: we need philosophy for technology.

To this end, you have created the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture, endowed with one million dollars. This year it has gone to the Australian philosopher Peter Singer. Can you explain why he was chosen? You could say it's akin to a Nobel Prize for Philosophy.

Thank you, this is exactly the aim. We started the prize five years ago to say, listen, philosophy and thinking are just as important as economics and physics. Therefore the idea is a little bit, as you say, like a Nobel Prize for philosophers. What we have been doing for years is awarding prizes to different people. This year the jury selected Peter Singer, an Australian philosopher who argues that although humans are wonderful, the world should not be so human-centric anymore. We affect the planet, as well as others, including animals, and we have got to have respect for other species. Among ourselves, we've got to treat each other as human beings, and we have to treat other species with respect as well. It all boils down to responsibility.

Nicolas Berggruen and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2019.

What does the Berggruen Museum in Berlin, which houses the collection that your father, Heinz Berggruen, built up with genuine treasures of modern painting, including countless artworks by Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti, or more than 120 Picasso pieces, among others, mean to you?

Well, Spain is very well represented. Most of the works on display at the Berggruen Museum in Berlin are by Picasso. My father was from Berlin, and that's why the museum is there. He was passionate about art, and he collected works from the 20th century and very classical artists: Picasso, Matisse, Giacometti, Paul Klee, Cezanne, and they all ended up in Berlin. The family, which includes me, has decided that we should continue giving our help and support. We have continued to acquire works by artists that fit with the museum, including Picasso, and fortunately, the museum is alive. It's interesting because, honestly, in Spain, you have some museums that are also supported by families, like the Thyssen in Madrid or Picasso museums supported by the Picasso family. Berlin is a very dynamic city culturally, and we try to play that role with the museum.

To summarize: Changing the world through ideas - could you give me some final thoughts on this?

I very much believe that ideas change the world. At the very least, they change the way we think and function as humans. If you look back through history, you see that most of the things that happen to us as humans in our societies and cultures have come from a few thinkers, and this has been true forever. The big things that have shaped our lives have largely come from religious philosophers or thinkers. In the West, we still live in the world defined by Socrates, by Aristotle, by Jesus Christ, and, more recently, thinkers like Kant, Nietzsche, or Karl Marx. In the East, you have the same, you have Lao Tzu, and you have Confucius. You have different thinkers who have shaped the way China is functioning today. So the inference of ideas is totally predominant. I really think ideas shape the world more than anything else, so the institute tries to give power to people who develop ideas. Sometimes the ideas are great, and sometimes the ideas are terrible, but they shape the way we go. Sometimes you don't know for a century whether the idea is good or not, and very often, the most influential thinkers are not very popular. By the way, all the people I have mentioned were not popular at all during their lifetimes. Jesus Christ died on a cross, Socrates was condemned and poisoned, and Confucius was in exile, same with Lao Tzu. They didn't have a good time then, which is why we need to support them now.

- Interview with Nicolas Berggruen - - Alejandra de Argos -